Translation – Postville, Iowa

Share:

Translated by Patrick Moseley

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: In Ohio, ICE agents arrested 114 employees of a landscaping company in two locations.

[Journalist]: It was a meat packing plant in Morristown and at least 100 people were detained.

[Journalist]: ICE reported 98 7-11 stores throughout the country seeking out undocumented employees.

[Journalist]: ICE agents arrested more than 100 undocumented workers.

[Journalist]: They arrested 32 immigrants during a raid at a concrete plant in Iowa.

[Daniel]: Maybe you’ve heard stories like these. Agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement —or ICE as it’s generally known— raiding factories or businesses where undocumented immigrants work. With the goal of detaining and deporting them.

Between October 2017 and July 2018, more than a thousand people have been arrested in operations like these —nearly fives times as many as the previous year. This is a direct result of Donald Trump’s anti-immigration policy.

But raids like these weren’t invented by the current administration. Not by a long shot. They have been a tool authorities have used for years.

And, generally, we hear these kinds of stories, stories about arrests, but we hear relatively little about what happens next, about the consequences, about how a community changes after a mass detention. How relationships between residents are transformed, how it affects its economy, its culture. The mark an event like that leaves behind.

And that’s exactly what today’s episode is about. What happened in Postville, Iowa, 10 years ago.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: In May, agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement raided Postville’s largest employer, a food processing plant on the edge of town

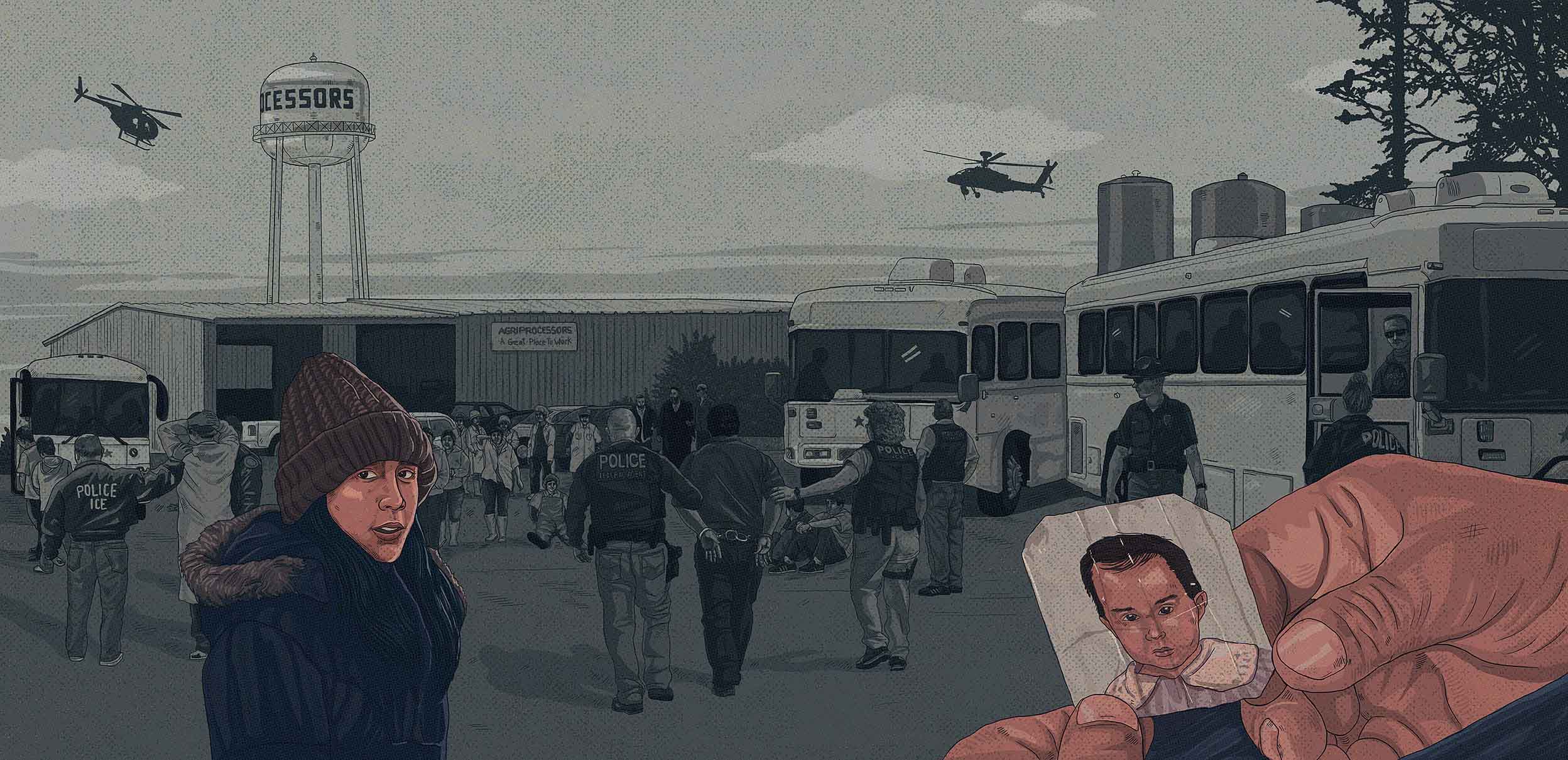

[Daniel]: In May of 2008, nearly 400 undocumented immigrants were detained, at a factory called Agriprocessors. The plant processed kosher meat, meaning that it was done in accordance with Jewish law. Of the workers who were detained that day, some 300 were deported, mostly to Guatemala.

And Postville was never the same again. It was a town of two thousand residents that was suddenly transformed.

[Andrea Patiño]: A lot of businesses closed, a lot of houses were just abandoned.

[Almudena Toral]: People moved away. A lot of jobs disappeared.

[Andrea]: A lot of the teachers had to work on a volunteer basis to keep the school open. They didn’t collect a salary.

[Almudena]: There were a lot of families that were separated and each family took a different path. Some families broke apart.

[Daniel]: This is…

[Andrea]: My name is Andrea Patiño.

[Daniel]: And…

[Almudena]: My name is Almudena Toral.

[Daniel]: They work on the Univisión Noticias Digital video team.

They visited Postville together in February of this year, 2018, to see how this place has changed 10 years after one of the largest raids in the history of the US.

Lisette Arévalo tells the story.

[Lisette Arévalo, producer]: To understand what happened in this operation, we need to explain the political context of the United States. After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the George W. Bush administration enacted several policies to combat terrorism and increase security in the United States. As part of this, they launched a plan called “Endgame”. Its objective was to deport all the undocumented people in the country in ten years.

[Andrea]: And the Postville raid was a part of this operation. It was supposed to be like a pilot. A pilot raid that would be replicated throughout the country.

[Lisette]: We’re talking about an operation involving helicopters, hundreds of federal agents and buses to transport the immigrants. It’s calculated that the US government spent nearly 5 million dollars on the raid itself, not counting the additional costs that came later. And at the time it was the raid in which the largest number of people had ever been detained at their place of employment.

[Andrea]: I think that in order to understand the impact of the raid, you need to imagine this super small town. It has two or three main streets with small stores.

[Almudena]: It has very small houses, mostly with one or two stories at most.

[Andrea]: Everyone is related. The person who works at a restaurant is the mom of the journalist who works at the local paper.

[Almudena]: It has two main roads and two restaurants: one of which is a very typical American diner and the other is a Mexican restaurant. That’s it, there are no other places to eat.

[Andrea]: In other words, it’s a very small community.

[Lisette]: But, why did ICE focus its attention on a kosher meat plant in a town as small as Postville, and not, for example, a city on the border, or a metropolitan area with a large number of immigrants?

[Andrea]: A lot of people told us it was because it was such a small area. It’s like a more controlled environment.

[Lisette]: In other words, because of its size and because it was such an isolated town, it was easier for ICE to control the operation than it would be in a city like New York, for example, or Los Angeles.

And, well, most importantly, ICE had been investigating Agriprocessorss for a few months because…

[Andrea]: Sholom Rubashkin, who was the person in charge, the company’s CEO at the time, was also violating a number of financial laws. Which the government was apparently aware of.

[Almudena]: And from there, as they started investigating financial abuses, other kinds of reports of abuse also surfaced, reports about with hiring and the abuse of undocumented immigrants. So they started investigating and, well, they were finding more and more.

[Lisette]: There were very clear violations of immigration laws: workers with falsified documents or social security numbers belonging to dead people. In many cases, it was the company itself that helped them falsify these documents.

But this is something you have to understand. According to everything we know about life inside the Agriprocessors plant, it was a terrible place to work. Beyond violating immigration laws, we’re talking about a place where the owners took advantage of the immigrants’ vulnerability.

They didn’t pay them very much for the hard labor of processing beef and chicken. They constantly threatened to report the workers to ICE if they didn’t work at the pace they wanted. They hit them. They didn’t let them use the restroom. They shouted at them. They made them work up to 17 hours straight. There were reports that there were minors without papers working there, being exposed to dangerous chemicals and handling large knives and saws to cut meat. All on top of the reports of sexual abuse.

After an eight-month investigation, ICE had obtained around 700 arrest warrants for the undocumented workers at Agriprocessors. And then came the day of the raid.

[Almudena]: May 12th, 2008 Jorge and Maribel, a Guatemalan couple, were in their home in Postville, Iowa.

[Jorge Castillo]: That day I didn’t want to go to work, honestly. I didn’t feel like going at all.

[Maribel Castillo]: I told Jorge that morning, “I have a funny feeling.” I told him: “Don’t go to work,” I said.

[Jorge]: “Ah, don’t go?,” I said. “Who’s going to support us if I don’t work,” I said.

[Almudena]: And they said goodbye like any other day, obviously not imagining that that day would change their lives forever.

[Lisette]: Jorge Castillo had arrived in Postville 6 years earlier. Other than working in an Evangelical church, his only job had been as a meat processor at Agriprocessors.

When he started at the plant, he worked in the area where they processed the pieces of meat after the animal is killed. They separated the clean meat, the bones and the fat. And he did this work for six to ten hours a day, every day, making minimum wage, a little more than $7 an hour. He had a short break for lunch and his supervisors didn’t even let him or his co-workers use the restroom.

After almost 2 years he moved to the chicken area, where the work was the same but with a kind of meat that was easier to handle.

And the conditions were the same: long hours, a very short break, without being allowed to use the bathroom. And on top of that, his boss required him to process as much meat in as short a time as possible. And if they didn’t do it…

[Jorge]: He was more than willing to hit you if you couldn’t handle it. Because they had worked out the time, how much time it took to do the work for that number of cows.

[Lisette]: Despite the poor treatment and the hard work, Jorge kept working there because it was good income for his family. His two daughters were going to school, they lived in a comfortable house and he had his own car. They had stability.

So, the day of the raid, Jorge said goodbye to Maribel, his daughters and his six-month old baby. He got in his car and went to work in the plant. Jorge was on the morning shift.

[Jorge]: I got to the company, that’s where the parking lot is, and everything was, well, ordinary, normal, there was nothing strange. Nothing.

[Lisette]: Like every other day, he went into the plant, put on his white coat, and went to his work station.

Meanwhile, Maribel was still at home. And…

[Maribel]: I heard a plane overhead, the helicopter. When I heard it, my neighbor came and said: “Maribel, go outside”. “What happened?” “Come on,” she said. “Look at that helicopter flying”, she said. “That’s immigration”, she said.

[Lisette]: And after Jorge had been at the plant for just 20 minutes…

[Jorge]: My brother-in-law came in shouting: “Hide! Immigration is coming.” Immigration and, like always, it was always a joke, that people were always making, since they knew there were a lot of illegals, to scare them, it was joke.

When they started shouting that they had already entered, then, it went really fast…

People were already really upset, they were already running from one side to another.

[Almudena]: They hid where they could. In the freezers, at super, super cold temperatures, in water containers, in every kind of hiding place you could imagine in a meat plant.

[Jorge]: They treated a lot of the people who hid like dogs. They beat them. Women were crying and a lot of men too. Then the officer arrived. He said anyone who moved would be shot. He said not to move. Soon everyone was surrounded by immigration.

[Almudena]: They gathered all of the immigrants together until they could determine who had papers and who didn’t. The ones who could show they had a passport or green card were allowed to go. The ones who didn’t, well they sat there for hours until…

[Jorge]: They put shackles on our ankles and waists, once we were chained together, they took us to the bus…

[Almudena]: Belonging to Immigration and Customs Enforcement and they took them to a city called Waterloo, which is about an hour and a half from Postville.

[Lisette]: They had arrested 389 people but not all of them were on the buses. About 25 were let go because they were minors and a little more than 50 women were let go —right there in Postville— because they admitted they were alone and no one would be able to take care of their children. But they left with an ankle bracelet that ICE could use to monitor them and they were prohibited from working indefinitely.

Meanwhile word started to spread around town. Maribel was at home, worried about her husband and scared that they might come for her. Then she heard a neighbor calling…

[Maribel]: “They got your husband. Your husband is in chains,” she told me. I felt that pain in my heart and it felt like I was falling down dead, and I said: “Oh no, it can’t be they’ve gotten my husband and taken him away.”

[Lisette]: They had taken him to Waterloo, the city near Postville, where ICE had rented a big stadium that’s normally used for rodeos and cattle shows. That’s where they left Jorge and the other detainees to wait to be processed by immigration agents. It was like a cattle corral where they set up a gigantic impromptu barracks.

[Jorge]: There were a few mats, like emergency mats, when there’s an accident on a mountain, the beds they gave us for that night were almost like that, for each of us to sleep on, and a really thin blanket. They took our shoes. If we went to the bathroom they shackled our feet and hands.

[Lisette]: Nearby there was a large wood-floored room —like a dance floor from the 50s— that had been adapted to look like a federal court. It was full of desks, chairs, computers, printers, and in the middle of the platform, there was the shield of the Department of Justice. The plan was to process those 306 detained persons in less than 72 hours. It was a huge show of power and authority by the Bush administration.

[Lisette]: While Jorge and the others waited to be processed. The residents of Postville were in a tremendous state of uncertainty. News of the raid spread through the city in a matter of minutes.

[Andrea]: It was an incredibly chaotic and painful day for everyone. You know, they didn’t know what to do.

[Lisette]: At school…

[Andrea]: A lot of teachers told us how they were trying to distract their students, continuing classes somewhat, trying to keep them calm.

[Lisette]: They separated the Latin students from the rest and took them to the school auditorium.

[Andrea]: And children were there, eh, in a group while they were trying to figure out who could pick them up. If they had a mother or father that wasn’t working at the plant that day or just didn’t work there at all. Or a cousin, an older sibling. There were people who had to be responsible for children who weren’t theirs.

[Lisette]: No one knew if the raid would carry over into the rest of the town. People who were at home started to flee.

[Gyora Bass]: When they heard about everything that was happening at the plant with immigration, they grabbed their kids and got in the car and left, leaving everything behind.

[Lisette]: Gyora Bass is a Jewish man who still lives in Postville now. He had a taxi service for employees at the plant and this is what he remembers from the day of the raid.

[Gyora]: Then, I open the door to the house and see how people had disappeared. The truth is I thought Jews felt the same when they were in Germany —in Nazi Germany— that the world was ending for them, that they had nowhere to go.

[Lisette]: All of the undocumented immigrants —whether they worked at the plant or not— abandoned their houses. But not all of them fled. Those who were separated from their families because of the raid opted to take refuge in the town’s church. Like Maribel, who left her house with her seven-month-old baby and picked her two daughters up from school.

[Maribel]: They took care of us at the church. There were Mexicans, Guatemalans, people from various countries, they gave us supplies and they gave us jackets, like to sleep, and… The food we needed every day.

[Lisette]: And Maribel and the nearly 400 people who were taking shelter there…

[Maribel]: They were crying, bitterly crying because immigration —after six in the afternoon— surrounded the church to get everyone, another raid. But there they told us that they couldn’t take us from the church because it was a greater crime, that migration was going to come in the church. So they told us that we had to be there.

[Lisette]: There is a law called the Sensitive Locations Law, for the US Department of Homeland Security, and it says that there are specific locations and circumstances where they cannot conduct raids, detain immigrants or question them, unless a supervisor authorizes it in circumstances that require immediate action.

There are several locations that are considered sensitive, such as schools and hospitals, as well as religious locations —like churches, synagogues, mosques and temples. Which meant that Maribel and the others were safe there at St. Bridget Church.

[Maribel]: We were all tossed in there. There was sympathy and there was sadness, the day it happened, because we were quiet like brothers and sisters, we were brought together, tossed like that, sleeping on the floor.

[Daniel]: Meanwhile the 306 immigrants in Waterloo were being interrogated, waiting to be processed, without even knowing if they were going to go to prison or be deported, or what was happening to their families in Postville.

We’ll be back after a break…

[Ad]: Support for this NPR podcast and the following message come from Squarespace. Faith is calling. It says that you need a new website. Build one yourself easily and with the support of the 24/7 award-winning customer service. Head to Squarespace.com for a free trial and when you’re ready to launch, use the offer code RADIO to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain. Keep dreaming. But make it a reality. With Squarespace.

[Promo Believed]: More than 20 years —That’s how long olympics gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar abused the girls and women who came to see him for treatment. “Believed”, a new podcast from Michigan Radio and NPR digs into how he got away with it for so long.

[Promo Code Switch]: This week on Code Switch —“La Bamba”. Why a Spanish language song with afro mexican roots is an all American anthem?

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, Maribel was in the church with her three young daughters, not knowing what was going with her husband, Jorge. And he was awaiting his sentence at the facility ICE had set up in Waterloo.

Lisette Arévalo continues the story.

[Lisette]: When a person violates immigration law in the US —because they don’t have documents, or their visa is expired, for example— the deportation process can take place in a number of ways: They can be deported immediately, they can leave voluntarily, or their case can be reviewed by an immigration court.

In the case of the Postville raid, what should have happened with the immigrants is that ICE should have brought them before an immigration court. There, the judge would have evaluated their cases and, if they found an infraction, they would authorize their deportation. Under immigration law in the United States, this is a civil offense. But the day of the raid, Jorge and the other detainees were processed as criminal offenders. And it all happened there, at the Waterloo stadium.

[Almudena]: They had brought interpreters and lawyers. They had brought judges, and all of this was in an undercover operation. No one knew what they were there for. They knew it was a federal job and that it was secret.

[Andrea]: It was something they had never seen before. People had never been processed en masse like they were there.

[Almudena]: There was one lawyer for every 20 immigrants. And in many cases they were lawyers who had no experience with immigration law. They were criminal defense lawyers.

[Jorge]: It was shameful how they took the guys in chains. And every time they took you to court, they treated you worse than a dog> chained at your feet, at your waist, with a metal plate here so you couldn’t move.

[Lisette]: It was a metal plate that was fixed to their chest that didn’t allow them to bend down. The lawyers and judges asked them if they had seen anything unusual in their time working at Agriprocessors: mistreatment, sexual abuse, or if they themselves had been victims of any kind of abuse. They wanted any information they could get on the people who managed the plant. They interrogated them about their falsified documents and they pressured them to sign their deportation orders. And many of them…

[Andrea]: Didn’t understand the judicial process very well. They didn’t understand what was happening or what they were signing.

[Jorge]: With the lawyer, they took us to the judge and we already knew to say, when judge asked us if we were guilty of the crime we had committed at the factory, of working illegally, we knew to say “yes”. So when he said to us> “You’re guilty.” It was like: “Yes, sir, I’m guilty. Yes, sir. Yes, sir.” Until he said you’re sentenced to six months in prison and you can’t come back to the United States for ten years.

[Lisette]: In 72 hours, nearly 300 immigrants were accused of the crime of aggravated identity fraud and were processed criminally, which had never happened before.

[Andrea]: And after that Jorge went to prison, first a prison in Chicago and then one in Louisiana.

[Jorge]: We got there and the officer said: “This is where you’re going to carry out the sentence.”

[Lisette]: Meanwhile, the news that Jorge and the others were in prison made it to Postville. Jorge’s nephew was one of them. Maribel was still at the church waiting to get news of her husband.

[Maribel]: But my fear was that they had gotten him and taken him away. He never spoke to me.

[Lisette]: And even though she was getting help from the people at the church and different organizations, Maribel felt desperate, anxious, not knowing what to do.

[Maribel]: We were there for three months and they took care of us there. And… But we did have that fear —all of us who were there— of going out during the day. We didn’t leave at all. We were… well, we were imprisoned more than anything.

[Almudena]: They found out that all of the immigrants were in prison and that the plan was for them to be there for quite some time. They didn’t know what was going to happen but they were probably going to deport them.

[Maribel]: Yes, I felt very hopeless. I felt like, uh, I was going crazy. I didn’t know anything about what was happening with him.

[Lisette]: Seeing the state she was in, the workers at the church and an NGO that was there helping the detainees’ families offered her something:

[Almudena]: “Look if you’re desperate to go back to Guatemala, we can pay for the plane tickets and you can go back.” And Maribel thought about it and said: “What am I going to do by myself, unable to work with three small girls, one of which is a baby?” She felt totally powerless and she decided to accept the offer.

[Lisette]: She had to make the decision on her own. Jorge hadn’t responded to the letters she sent to the prison. So, with her three children, Maribel went to her apartment in Postville and packed only her daughter’s clothes. The rest of her belongings —like her own clothes and Jorge’s, the electronic appliances, the furniture— was all left there. She couldn’t bring everything. Knowing nothing about her husband’s situation, she got a plane and left. She said that when she arrived she felt happy to be back.

[Maribel]: But after I was back in Guatemala for two months, I felt sad. I felt very sad and I would say: “Why did I come here? I don’t have any money.” And Jorge is in jail. He hadn’t gotten out. I don’t have money. How am I going to support myself?

[Andrea]: But in those six months Jorge also didn’t… didn’t have a clear idea of where they were. They weren’t able to contact one another. He didn’t know that Maribel had decided to go to Guatemala.

[Lisette]: And by the time he finished his sentence —six months later— Jorge was one of the nearly 300 people who were deported to their country of origin.

[Jorge]: Most came with just the rubber sandals they were given in prison. Some were barefoot. They gave us the same clothes that we had been taken in, while we were working, the clothes we came here in. When we crossed the border, we were coming as free people. But the whole way from prison to the border, we were in chains.

[Lisette]: Maribel had been in Guatemala for nearly two months when they told her that Jorge was being deported. Jorge’s sister found out that her son and Jorge were going to arrive in a few days. So they went together to pick them up at the airport.

[Andrea]: And in fact, both of them say, Jorge in particular says, that when he arrived and he saw Maribel with their daughters, he was a little upset.

[Jorge]: It was such a surprise when I get off the plane and left the airport and saw my family there. Seeing my daughters, well… I was even a little upset, to be honest.

[Maribel]: Well, when I saw him, I didn’t recognize him, because when he landed here in Guatemala, his hair was really long. But in the end, when I got a good look at him, it was him. But, well, I felt happy, but then it wasn’t a happy moment anymore, it was sad. Because the two of us met here and he said to me: “Why didn’t you stay in Postville, I would have come back. I… my decision was to go back to Postville and go to work and see you.”

[Jorge]: Because being there, they would have been studying if she hadn’t come, do you understand? They would already be very far along in their studies.

[Maribel]: I told him the reason we came was that all of the money was gone, and it wasn’t just coming here. I wasn’t thinking about the girl’s future. Because he had brought them to give them a better future and today there’s nothing I can do. Because now I’m here in Guatemala.

[Lisette]: Since then, the Castillo family has not returned to Postville. They live in San José Calderas, in the foothills of Volcán de Acatenango and Volcán de Fuego. When Andrea and Almudena went to visit them, they saw that Jorge and Maribel…

[Almudena]: Had built a small house with them money they had managed to save in Iowa…

[Lisette]: Before they whole Castillo family went to Postville, Jorge had been there alone for three years and he sent Maribel the money they used to build the house they live in now.

[Andrea]: It’s a small three room building. So, they’re on the same side and it opens up to the little patio. It’s very small and that’s where they have their horse and they have little ducks. It has a very nice yard and… well, they still haven’t been able to build a bathroom so they have a designated place in the yard where they go to the bathroom.

[Almudena]: And that’s where they live today. Where at least they have a small house to live modestly in.

[Lisette]: There, Jorge and Maribel work in the field, gathering fruit and vegetables that they sell in a market once or twice a week. They make about 1,200 quetzals from these sales, which is about 160 dollars. Besides that, Jorge works with his cousin as a tour guide on the Volcán de Acatenango, where they make 40 dollars every time they go up the volcano. But these jobs aren’t steady and they don’t make up a fixed monthly income.

Their two older daughters —who were going to school in Postville— help Maribel selling what they can. They are 15 and 16 and they don’t go to school anymore because they don’t have money to pay school supplies. The youngest daughter is five and she is going to school, but…

[Almudena]: The family knows that she’s not going to be able to continue going much longer because even though it doesn’t cost a lot of money, the uniforms and notebooks and all that are expenses they can’t afford.

[Lisette]: Meanwhile, their third daughter, Jeidy —who was born in the United States and moved to Guatemala when she was barely 10 months old— went back to Postville in 2010, when she was 7, with a friend of the family.

[Almudena]: This woman had lived through the raid as well, but she had been one of the women who was allowed to leave with an electronic ankle bracelet and she had managed to formalize her situation. Then, one day she took a trip to Guatemala to visit —for vacation— and she offered to Jeidy’s parents to take her so she could be in the US and keep her own daughter company and also continue her studies.

[Lisette]: It’s been 4 years and they haven’t seen her since.

[Maribel]: It makes me very sad, because I would love to be a dove and fly to see her but I can’t.

[Lisette]: A lot of families were separated after the raid and couldn’t be reunited for years. Others were never reunited and after so much time being separated, they stopped being families.

[Almudena]: Anecdotally, in this town there are a lot of stories about how the younger generation suffered the psychological consequences of the raid as well as how they suffered from being physically separated.

[Lisette]: Like Tommy Chávez. He was 12 years old when the raid took place and his parents were working at the plant. Both were detained by ICE but they let his mom go with an ankle bracelet. His dad was deported.

[Tommy Chávez]: In the days after the raid, the town was very sad because you didn’t see people anymore. Now, where there had been a happy town, it wasn’t the same anymore. People lived in fear here in town. People stopped leaving their houses.

[Lisette]: A constant fear that they could be found at any moment. That in an instant, their lives in the United States could be over. And Tommy, his brother and his mom felt that way too. They boys stopped going to school and their mom barely left the house. But a few months after the raid, the three of them left Postville to live in Minnesota.

[Tommy]: We wanted to try to find a better future for ourselves. A place where we weren’t going to be reminded of the tragedies that happened this town.

[Lisette]: Starting with the raid.

[Tommy]: I used to see the United States as a place where people could come to seek a better future without any problems. After that day, that was when I felt like my eyes were opened. That day I felt that the United States was unfair to immigrants.

[Lisette]: But the raid didn’t just affect young people like Tommy and the other families that were separated. It affected the town, too.

[Almudena]: The immigrants weren’t the only ones who suffered economically but the members of all of the communities did too. And the residents of Postville and all of Iowa suffered an economic impact.

[Andrea]: There were several businesses that closed as a result of the raid. If you lose half of the population over the course of a few days, there aren’t going to be customers for the few local restaurants there were or the local laundromat.

[Almudena]: There was also a large impact demographically at the population level. The population was reduced drastically. People moved away and a lot of jobs disappeared.

[Lisette]: Immediately, the day after the raid, a third of the population had left Postville. And that was just the start of the exodus. In the following days, weeks, months… more and more people left… In the end the town came to lose almost halve of its population, or nearly 1.000 people. And that’s why…

[Andrea]: A lot of houses were just abandoned.

[Lisette]: By October of that year, almost 60% of the property in Postville was seized by banks.

[Andrea]: That’s a very high number. And that was a direct result of the raid.

[Lisette]: As for the kosher meat processing plant Agriprocessors and Sholom Rubashkin, the company’s CEO—who was the reason the plant was being investigated in the first place—, he didn’t go to prison right away. In early November 2009, Rubashkin was arrested and accused of a total of 72 immigration violations and 91 charges of financial fraud. And in June of 2010…

[Almudena]: He was sentenced to 27 years in prison for financial crimes, but not for the charges related to hiring undocumented immigrants or abuse of immigrants.

[Lisette]: The federal judge decided to withdraw the 72 immigration charges against him. She was taking into account the fact that Rubashkin had already received a longer sentence for the 86 financial crimes and that lifting the immigration charges would spare them a trail that would be both costly and inconvenient to the witnesses.

But the immigration charges —that is, hiring people without papers— had been the main motivation for the raid.

[Lisette]: The plant stayed open but the Americans who lived in Postville didn’t want to work there: the pay was bad and the work was very hard. There were bad smells and they had to cut meat and handle animal parts.

[Andrea]: After the raid it was very hard to find employees.

So the owners tried to fill those jobs any way they could.

[Andrea]: They brought in ex-convicts from all over the country, people from shelters, mental institutions in Texas, North Dakota, and the south side of Chicago. They brought people from the island nation of Palau.

[Lisette]: In other words, people who were very different from the Central American and Mexican families that worked in the factory before the raid.

[Andrea]: People came that had never lived there alone, you know, with… without families. So that produced, well, certain problems.

[Lisette]: You can replace a worker, but what you can’t replace so easily is the family and the culture around them. What was lost was the community that had grown around the factory.

And these new workers didn’t perform as well as the ones before.

[Andrea]: And well, after those waves of workers that didn’t work out, the plant eventually… went bankrupt.

[Lisette]: And just five months after the raid, the factory closed. This was a very hard hit for the Jewish community in Postville. The large majority of them worked there or were connected to the plant in some way. Like Gyora Bass, the man who saw the immigrants fleeing Postville, who had a taxi service for employees of the plant, or the Fridge as he calls it. When the raid happened…

[Gyora]: I lost my job immediately, because my job was… They called me and they would say: “You need to bring this guy. You need to pick him up.” All that. And if no one’s working at the Fridge… If the Fridge isn’t going, I don’t have a job.

[Lisette]: Unlike many Jewish families, Gyora stayed in Postville.

[Gyora]: I think that I still haven’t recovered from that.

[Lisette]: A little more than a year after the raid, a Canadian multi-millionaire, Hershey Freidman, bought the plant that had been Agriprocessors and named it Agri Star. At that time Somalis started arriving with refugee status.

[Andrea]: The jobs were never put back in the hands of Americans because the conditions continue to be very difficult and the salaries continue to be very low for someone from here. And effectively, it was one immigrant community that replaced another.

[Almudena]: When you take stock of what happened, you see that it was all losses. There were emotional losses because of families being separated. There were economic losses that the town and the whole state suffered.

[Lisette]: Remember that the raid in Postville was an experiment, a pilot project for a program that supposedly was going to deport every undocumented person in the country in just ten years.

But it didn’t work out that way.

In the following years, little by little, several Central American families that had left after the raid starting coming back. And other Latin American immigrants started to arrive. And if you really look at the impact of the 2008 raid, today, you’ll find that the population of Postville is more diverse than ever, and the Latino population percentage is nearly double what it was ten years ago. Almost 40 per cent.

[Daniel]: In December 2017, President Trump reduced Sholom Rubashkin’s sentence. Instead of 27 years, he only served 8. Now he lives in Brooklyn, New York with his family.

Andrea Patiño and Almudena Toral are journalist with Univisión and they work on the video feature team. We’d like to thank them and Univisión for letting us use audio they recorded for their documentary “America First, el legado de una redada migratoria.” You can find a link to their documentary on our web page.

Lisette Arévalo is an editorial intern with Radio Ambulante. She lives in Quito, Ecuador.

This story was edited by Silvia Viñas, Camila Segura and me. Music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano. Our intern Andrea López Cruzado did the fact checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Jorge Caraballo, Patrick Moseley, Ana Prieto, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas. Victoria Estrada is our editorial intern. Carolina Guerrero is our CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Every Friday we send out an email in which our team recommends movies, music, series, books and podcasts that inspire us. It has great links for you to enjoy all weekend. You can subscribe on our website at radioambulante.org/correo. I’ll repeat: radioambulante.org/correo. If you use Gmail, check your spam folder and put our email in your primary inbox so you don’t miss it.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.