Laurinha Wants to Play – Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Today’s story starts in June of last year, during the Women’s World Cup.

It was a world cup that marked a clear before and after in women’s soccer, especially in Brazil. There was more publicity than ever, and something also happened that isn’t very common in that country: people met up in pars to watch the matches with their friends. That’s common for the men’s world cup, obviously. But that level of enthusiasm for the women’s world cup had never been seen before, at least not at such a large scale.

Cart vendors even started selling the team captain Marta Vieira da Silva’s jersey. It was the first time her jersey was for sale alongside the superstars of men’s soccer, jersey’s like Neymar’s, Dani Alves’s or Pele’s, for example.

One of the reporters of this story — Brazilian journalist Cláudia Jardim — approached a cart vendor in São Paulo. She wanted to measure people’s enthusiasm for the world cup, and it seems to her that a good way to do it was through the sales of Panini, the classic sticker books with professional players, but on this occasion, she wanted to know what sales for the women’s national team were like.

[Cláudia Jardim]: Oi, tudo bem? Tem álbum de figurinha da seleção feminina?

[Daniel]: And what she found surprised her.

[Vendedor]: Chegou, chegou, vendeu bem, ai esses dia a Panini recolheu tudo.

[Cláudia]: Mas como é que foi, assim? Quantas figurinhas você vendia por dia?

[Vendedor]: Uma média de cem figurinhas por dia.

[Daniel]: The vendor said that sales were good, around 100 sticker packets a day.

[Vendedor]: Foi uma média boa para ser futebol feminino.

[Daniel]: But he couldn’t help but add that it’s a good average considering that they’re talking about the women’s national team.

And then, Cláudia asked which Panini sold more, the one for the men’s team, which was playing in the Copa América, or the women’s national team. Both tournaments were happening at the same time.

[Vendedor]: Então… as duas tava (sic) meio empatada, mas tinha as vezes que a feminina ganhava. Vendia mais no dia do que a Copa América.

[Daniel]: The vendor told her that there were days when he sold more Panini of the women’s national team than the men’s.

[Vendedor]: Ah, me surpreendi né? Por ser futebol feminino a gente acha que é uma coisa assim que ninguém liga, mas…

[Daniel]: The vendor was surprised himself when he did the math. The sticker book of the women players was a commercial success despite the fact that the Brazilian team didn’t make it that far. They lost in a Round 16 match against France, who was hosting the World Cup.

Brazil has never won a women’s world cup. The captain and star of the team, Marta, had one great hope: that this time they would finally do it. After the match with France, once the Brazilians were eliminated, journalists and TV cameras approached her. She looked very upset.

[Marta Vieira da Silva]: É, lógico que emociona, o momento é muito emocionante. Eu queria estar sorrindo aqui ou até chorando de alegria.

[Daniel]: Marta couldn’t hold back her tears. She said that she would rather be smiling or crying with joy. And the interview became a kind of unburdening.

[Marta]: E o futebol feminino depende de vocês para sobreviver. Então pense nisso, valorize mais. Chore no começo para sorrir no fim.

[Daniel]: Marta asked the new generations of Brazilian women players to fight harder. She was reaching the end of her career and the future of women’s soccer depended on them.

This clip went viral and was commented on a lot on social media because she’s talking about something very important: the issues facing women who want to play soccer.

There are thousands of girls in Brazil who want to be the next Marta and many of them face the same obstacles that she did when she started playing professionally 20 years ago.

In today’s episode, we’re going to follow one of those players. Irene Caselli and Cláudia Jardim are the reporters bringing us this story. From the state of São Paulo, this is Cláudia.

[Cláudia]: At first glance, Laura Pigatin’s room looks like a lot of 16-year-old girls’ in Brazil. On her bed, there’s a teddy bear with a red heart on its chest. On the pink walls, you see a poster of Cristiano Ronaldo.

In the corner, there’s a very organized desk, and on the desk…

[Laura Pigatin]: Aqui tenho as minhas medalhas,

[Cláudia]: On a very tidy shelf…

[Laura Pigatin]: ...têm várias que são especiais para mim, mas têm algumas que são muito especiais…

[Cláudia]: This is Laura, and she’s showing us the dozens of medals and trophies she’s won in local soccer tournaments. She says they’re very special to her.

Laura lives with her family in São Carlos, a city of more than 250,000 people that’s three hours outside of São Paulo.

São Carlos is halfway between the countryside and the city, and it revolves around the Federal University, which is headquartered there. There are a lot of students. They come from all over Brazil and other parts of the world.

Social life is limited to the malls, and despite being a city full of young people, it feels like nothing happens here.

[Andrea Pigatin]: Moramos numa cidade pacata.

[Cláudia]: This is Andrea, Laura’s mom.

[Andrea]: Na qual não tem, não tem muita diversão, não tem muita coisa para se fazer, nos finais de semana a gente se encontra com os amigos. Nos reunimos, ora….

[Cláudia]: She describes São Carlos as a peaceful city, where there aren’t a lot of options when it comes to entertainment, other than hanging out with friends.

[Andrea]: E atrás do futebol da Laura, né? que é uma grande…

[Cláudia]: Except for soccer. Laura’s soccer turns into a great source of entertainment for the whole family, Andrea says. Besides, soccer is an excuse for families and friends to gather. They all meet at friends’ houses to watch a match on TV or go in a group to watch the local teams play.

For the Pigatins, that’s the big family tradition. Lauro, her dad, had always liked soccer and Laura grew up watching matches on TV with him and her older brother.

As a little girl, Laura would spend a few hours at her grandparents’ house, and she was surrounded by soccer there too. Her grandfather gave her jerseys, hats and anything else that had the logo of São Paulo, his favorite team. At that time, Laura said she was a fan of her grandpa’s team, until…

[Laura]: Daí, estava jogando acho que o São Paulo e o Santos e o Santos goleou o São Paulo, né? Era época do Neymar, do Robinho, do Ganso…

[Cláudia]: Laura remembers the day when Santos, her dad and brother’s team, scored on São Paulo, her grandfather’s team and the one she supported at the time.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Locutor]: Contraataque do Santos. Robinho! De letra!

[Cláudia]: On the field, there were stars like Neymar and Robinho playing. And it wasn’t easy to take her first upset in soccer.

[Laura]: Eu estava assistindo o jogo, sentada no sofá, e o Santos começou, ganhou o jogo e eu fiquei brava, né, triste, e acho que até chorei me lembro…

[Cláudia]: Laura remembers that she was watching the game on the couch and she was upset because Santos beat her team. She cried, disappointed, and threw her Club São Paulo gear her grandpa had given her in the trash. Santos became her new passion.

[Laura]: Daí meu pai comprou roupa do Santos pra mim e eu virei santista, sou santista até hoje.

[Cláudia]: Her dad ran off to buy her a jersey for her new favorite team, which is essential for becoming a real fan of the club. Since then, Laura has been a fan of Santos, Pele’s team.

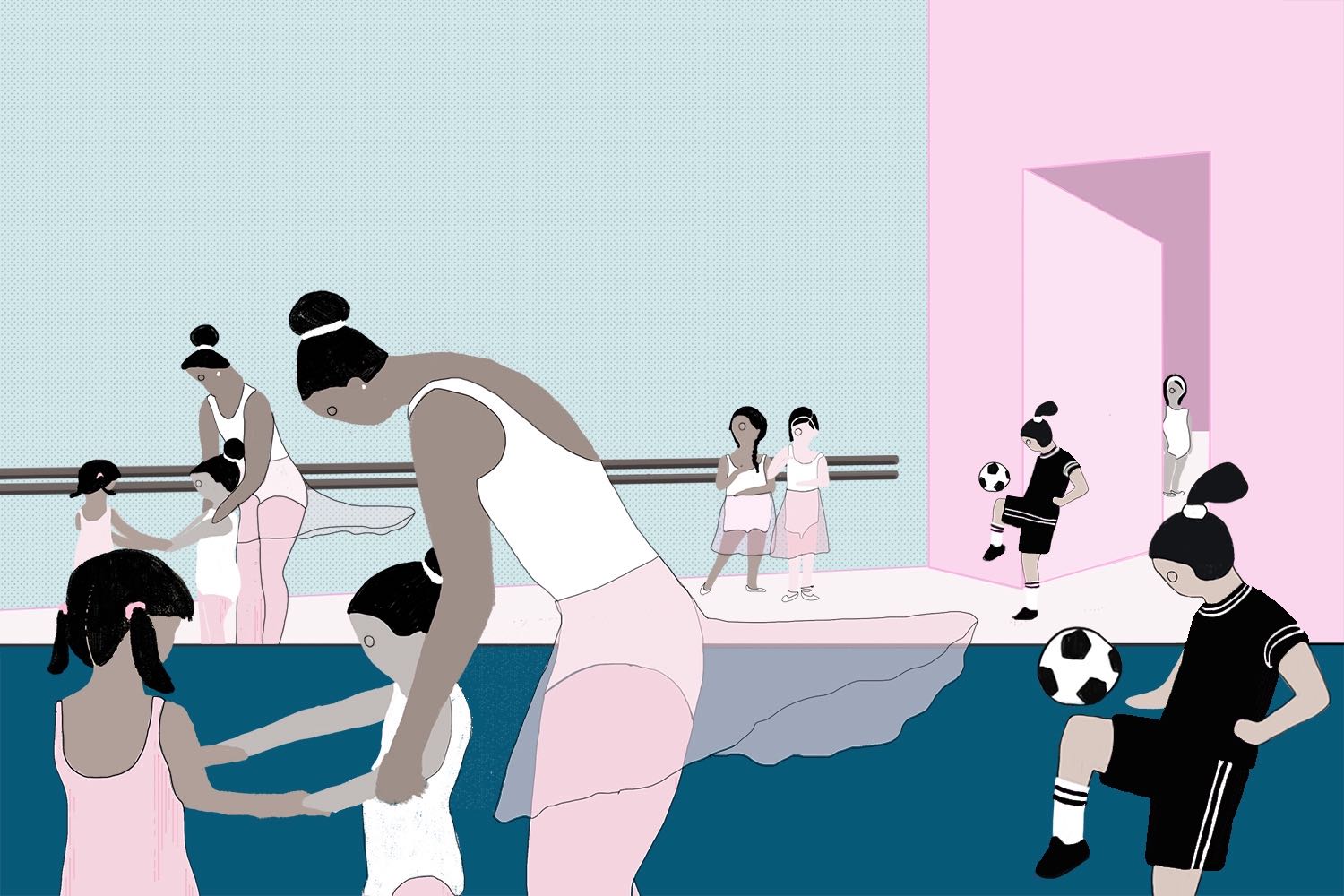

Her real initiation into soccer came when Laura was five. One day, her dad went to pick her up from preschool, and the teacher told him that Laura was the only girl in class who had decided to take soccer classes instead of ballet.

[Laura]: Era futebol para os meninos e ballet para as meninas, só que eu não queria fazer ballet, eu sempre quis fazer futebol, né, sempre gostei de futebol.

[Cláudia]: What was “normal” in quotes, was soccer for boys and ballet for girls.

[Lauro Pigatin]: A gente achou estranho e riu né? A gente acabou rindo, a gente achou engraçado, não estranho, a gente achou engraçado. E vamos ver o que qué vai dar isso.

[Cláudia]: This is Lauro, her dad. He says that it seemed like an amusing choice to him, but he didn’t think it was odd.

In a certain sense, Laura had always been like that. She asked for toys that were normally associated with the kinds of things boys like, like a Superman costume or toy tractors.

And the family was happy to get her the gifts she asked for. Andrea says that she was never one of those moms who thinks that girls should only play with dolls, though she also had a few.

[Andrea]: Às vezes eu penso na Laura, que ela não tem boneca, mas aí eu lembro que também nunca tive boneca, né? E meu negócio era brincar na rua, jogar bola, qualquer tipo de esporte.

[Cláudia]: When she thinks that Laura doesn’t have a lot of dolls, Andrea says that she didn’t have many either, and remembers how as a little girl she would go out and play soccer in the street and do all kinds of sports.

And they didn’t care. In fact, they liked that she was playing soccer. And Andrea…

[Andrea]: Apoiei desde o começo.

[Cláudia]: Supported her from the start.

[Andrea]: Eu achei normal ela ir, era muito bonitinha ela montava na van, toda vestidinha lá de futebol no meio dos meninos.

[Cláudia]: To her, it seemed like a normal decision for Laura, she thought it was cute — bonitinho — to see her, in her soccer uniform getting into the van that took her and her teammates to practice.

It was 2009 when Laura started taking soccer classes at school, and since it wasn’t the most popular game among girls her age, Laura got used to having boys as teammates.

[Laura]: Me sentia supertranquila, sim, me divertia, meus melhores amigos sempre foram os meninos mesmo.

[Cláudia]: And she liked that her best friends were boys.

She was always fascinated by everything having to do with soccer. She played a lot in the backyard of her house, after school…

[Laura]: Brincava de futebol aqui no gramado aqui de casa. Então, acho que eu sempre fui ganhando essa a paixão já pelo futebol, desde pequena mesma. A gente brincava de bonequinhos, sabe, de futebol, jogava videogame de futebol.

[Cláudia]: She liked playing out soccer matches with plastic toys or playing video games… about soccer, of course.

When Laura was seven years old, in 2011, after taking her first classes at school, a friend of the family started organizing games of futsal — indoor soccer — which is played with five players per team, indoors, on a smaller field, with a much faster style of play.

Laura was part of the team, and she was still the only girl. And because she was the exception, she got the crowd’s attention. Mostly it was other kids’ parents, but neighbors came from other cities in the state of São Paulo where the friendly matches were organized.

[Laura]: E todo mundo achava legal, né, as pessoas da cidade, ah o time lá da menina, e o time ficou conhecido como o time da menina. Tudo mundo ia assistir porque eu era uma atração mesmo.

[Cláudia]: Laura says that the team became known as “the team with the girl” and soon she became an attraction in the cities she passed through.

But Laura wanted to play regular soccer, on grass, in a big field. But it wasn’t so easy.

[Laura]: Eu jogo numa equipe masculina porque não tem equipe feminina na minha cidade, para a minha idade. E por isso é que eu tenho que jogar com os meninos.

[Cláudia]: In her city, she says, there are no girl’s teams for girls her age.

[Laura]: Mas, eu sempre quis jogar assim num time feminino, né, jogar com as meninas, porque eu acho mais legal. Não que eu não gostava (sic) de jogar com os meninos, gostava, mas é legal assim jogar assim com alguém, com alguma menina, né.

[Cláudia]: She always wanted to play on a girls’ team, with girls, because she thought it would be more fun. It’s not that she didn’t like playing with the boys. She did. But she would have liked to play with girls.

In Brazil, there normally aren’t tournaments for girls under 14. Unless they live in São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, big cities that have more options, girls have nowhere to go.

So Laura was only left with the option of playing indoor with the boys.

When she was 10 years old, a coach went to a friendly indoor soccer match that Laura was playing in.

[Rogério Pereira]: E aí eu vi que tinha uma menina jogando no meio dos meninos, né.

[Cláudia]: This is Rogério Pereira, the coach for ADESM, a sports association of the São Paulo metal workers union.

[Rogério]: Procurei saber quem era a mãe dela e eu convidei ela para vir.

[Cláudia]: Rogério says that he saw the girl playing with the other boys and went to speak with Andrea, to invite Laura to practice with his team.

[Andrea]: Aí eu tava sentada na arquibancada veio aquele moço de chapéu, de boné lá falar comigo, assim, eu até assustei no começo, nossa, mas que é que esse moço quer comigo né?

[Cláudia]: Andrea remembers she was sitting in the bleachers when Rogério, who was wearing a hat, walked up to her. It seemed odd to her that a stranger was walking up to her.

[Andrea]: Aí ele, e você que é a mãe dela?

[Cláudia]: “Are you the girl’s mom? Does she play outdoor soccer?,” Rogério asked.

[Andrea]: Eu falei não, ela está jogando só quadra agora.

[Cláudia]: At the time, Laura was only playing indoor soccer.

[Andrea]: Leva ela lá pra treinar lá comigo, eu treino lá no sindicato?

[Cláudia]: Rogério offered to take her to train with his team.

[Laura]: Daí minha mãe achou, assim, meio estranho aquele cara me chamando, tudo.

[Cláudia]: Laura says the invitation struck her mother as odd, but she asked her older brother to take her to a practice.

[Laura]: Eu fui lá. Fui lá treinar no meu primeiro dia de treino lá com os meninos…

[Cláudia]: It was the first time Laura played with a regular soccer team. She was excited, but at first it wasn’t easy at all.

[Laura]: Quando cheguei lá todo mundo ficou olhando, né, assim, né, achando meio estranho no começo, ficando meio duvidando, assim.

[Cláudia]: Laura remembers that the first day all the other boys stood there staring at her in surprise. It was the first time a girl was training with the team, and they didn’t know if she could really play.

[Laura]: Mas dentro do campo eles viram que eu sabia jogar sim e acharam super-legal, né. Sempre me apoiaram, nunca houve nenhum tipo de preconceito por parte deles não.

[Cláudia]: But as soon as they saw her in action, things changed. Her teammates were quick to accept her —without prejudice— because they realized she could play.

Laura’s family saw the chance to join ADESM, the boy’s team, as a blessing that would allow her to take part in official competitions organized by the state.

There were no competitions for girls, so they didn’t care that it was a boys’ team.

[Lauro]: Então foi tudo de bom para a gente a ADESM.

[Cláudia]: “ADESM was the best thing that could have happened to us,” Lauro, her dad, says.

Having Laura on his team meant a lot to Rogério.

[Rogério]: Até pelos meninos entenderem a importância de ter uma menina no projeto, ter uma menina jogando futebol com eles e até para quebrar alguns paradigmas, né.

[Cláudia]: Because having a girl on the team, he says, made the other boys understand what it was like to play with a girl, to break stereotypes.

But for Laura to join the group, they had to sort out a few practical matters. They may seem like silly details, but when it comes time to play, they’re very important. For example: changing before the game presented new situations for Laura as well as her teammates. She would go into the locker room first, and then, after Laura was done changing, the other boys came in.

On one occasion, Laura had already gone into the locker room when Andrea went up to the door. There were a few teammates watching the door. They didn’t recognize her as Laura’s mom and yelled at her…

[Andrea]: Não tia não entra, não, a Laurinha tá aí, ela tá tomando banho.

[Cláudia]: Not to go in because Laurinha was taking a shower.

[Andrea]: …que nem a mãe podia entrar.

[Cláudia]: Not even her mother could go in because her teammates had gotten very strict about this rule. And when there was no changing room, Laura would improvise with her mother’s help.

[Laura]: Eu já tive muitas várias vezes que me trocar dentro do carro, até teve um dia que tive que trocar atrás de uma árvore, minha mãe me ajudou.

[Cláudia]: Several times, she had to change in the car, and even behind a tree once.

Really it’s impressive because Laura transforms when she comes out of the locker room and takes the field. Irene — the co-reporter of this story — and I have spent a lot of time with her, with her family, and normally she’s a shy girl, and you can tell.

When we went to see her at school, Laura was sitting in the front of the class, quietly, sort of hunched over, with glasses on. But when we went with her to the field for the first time, we saw a transformation. With her soccer uniform on and her hair up in a ponytail, Laura stands up straighter and looks stronger. She reflects a kind of confidence that you don’t see off the field. It’s as if her real personality only comes out there — and it comes out strong.

[Laura]: Lá eu fico mais à vontade, eu quero ganhar, né, sou muito competitiva, sempre quero ganhar, então dou meu máximo.

[Cláudia]: She says the field is where she feels most comfortable. She’s very competitive; she does everything she can to win. And people started noticing. When her team traveled to other cities, the people who watched the match were surprised at how well she played. It got people’s attention that the only girl on a team full of boys was the best player on the field.

A lot of people went up to her after the games.

[Laura]: Sim, várias pessoas comentavam, até nas outras cidades, e pediam até para tirar foto comigo, falavam que queriam autógrafos…

[Cláudia]: To ask for her autograph or take a picture with her.

When I asked Laura if she had any pre-game ritual, she responded with the team’s chant:

[Laura]: Um, dois, três, oooooooô, Ferrinha!

[Cláudia]: Ferrinha! That’s what they call Ferroviária, the team she’s played for since 2018. That’s how it sounded in Laura’s room, but at a real match, it sounds more or less like this.

(CHANT SOUNDBITE)

[Cláudia]: One day, Andrea was at the beach with Laura, and her daughter was practicing some plays in the sand with the ball, and because she was so good, the other people there started to notice her. Her mom was watching her from a kiosk on the beach and heard two men talking about her.

[Andrea]: “Olha aquela menina como joga bola”, porque ela era uma atração quando a gente ia pra praia, o povo parava e ficava olhando, né.

[Cláudia]: “Look at how that girl plays,” one of them said. A little later his friend said:

[Andrea]: “É, pena que daqui a pouco ela vira homem. “

[Cláudia]: What a shame that pretty soon “vai virar homem“, she’s going to turn into a man.

It’s not an unusual comment. And it’s not just in Brazil. You hear similar comments throughout Latin American and the world, of course. There’s a very generalized view that soccer is too masculine for women. Usually with the implication that women who play soccer are inevitably going to be lesbians.

Not everyone thinks that way, of course. But that comment annoyed Andrea.

[Andrea]: De onde ele tirou isso, ela é uma criança ainda jogando bola. E se ela quiser ser homem, se ela quiser ser lésbica é a vida dela.

[Cláudia]: She says she thought it was absurd, that she didn’t know where that man got those ideas. We’re talking about a girl playing with a ball. Besides, it’s none of his business. It’s Laura’s life.

It’s clear to Laura too.

[Laura]: Eu acho que não tem nada a ver, para mim, na minha opinião não tem nada a ver, cada uma escolhe o que vem de você mesma. Cada uma escolhe o que quer ser, né?

[Cláudia]: She says those things have nothing to do with each other. That everyone is free to decide what they want to be.

Even though Laura’s parents thought comments like that one were absurd, the prejudices against her daughter started to become a concern, even during matches.

One day, Laura was playing with the boys in a championship. Her team was winning and Laura was playing a particularly inspired game.

[Laura]: E uma mãe, né, acho que eu driblei o filho dela, sei lá, ela começou a falar nossa, lugar de menina é brincando de boneca, o que você está fazendo aí?

[Cláudia]: Laura says that during a play, she dribbled past a boy and heard a mom on the bleachers shouting: “What are you doing there? A girl’s place is playing with dolls.”

Andrea was in the stands, watching her daughter play and she had to take a deep breath to stay calm.

And Laura wasn’t intimidated. On the contrary, she kept playing with even more passion. But tensions rose when she made a spectacular play to dodge that same boy.

Laura advanced on the goal. In that same play, the boy lost his balance and fell to the ground. The boy’s mom couldn’t handle it and started yelling even louder:

[Andrea]: Dá um soco na cara dessa menina.

[Cláudia]: Punch that girl in the face.

Andrea couldn’t believe it.

[Andrea]: Onde já se viu uma mulher falar para um menino bater numa menina… que se ela estava louca, a gente não incentiva a agressão no esporte, não é isso.

[Cláudia]: Where have you ever seen a woman tell her son to punch a girl. Andrea says that the woman was acting crazy. You can’t encourage aggression in sports. That’s not how it works.

That’s why ahe decided to confront her.

[Andrea]: Falei pra ela que ela sim tinha que ter ficado dentro da casa dela lavando roupa, cozinhando porque esporte não era aquilo.

[Cláudia]: And she told her that she should have stayed home doing laundry and cooking, if she was going to support her son with that attitude.

[Daniel]: What happened to Laura isn’t an isolated incident. Women’s soccer in Brazil reflects a much larger problem: sexism. Traditionally, soccer fields have been spaces reserved for men. So much so that in the past there have been women who were arrested just for playing soccer in the street.

After the break, the ban in Brazil that kept women off the field, and what happened with Laura. We’ll be right back.

[Code Switch]: Whether it’s the athlete protests, the Muslim travel ban, gun violence, school reform, or just the music that’s giving you life right now, race is the subtext to so much of the American story. And on NPR’s Code Switch, we make that subject, text. Listen on Wednesdays and subscribe.

[Life Kit]: NPR’s Life Kit is like a friend who always has great advice on everything. From how to invest, how to get a great work out, we bring you tools to help you get it together. Listen and subscribe to NPR’s Life Kit All Guides to get all of our episodes on all of our topics. All in one place.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, the co-reporter of this story, Cláudia Jardim, was telling us the story of Laura Pigatin, a girl who dreams of being the next Brazilian soccer star, despite the prejudice women and girl players face. Prejudices that have clear roots, that come, in part, from laws the country once had.

Co-reporter Irene Caselli continues the story.

[Irene Caselli]: Like in other places in the world, women’s soccer was banned in Brazil for a long time: almost 40 years.

A decree in 1941 established that: “Women shall not be permitted to practice sports that are incompatible with the condition of their nature.” That, of course, included soccer. The list of banned sports included weightlifting, baseball, and martial arts.

During that period of authoritarian governments in Brazil, women were expected to stay in the private sphere, to be protected and controlled, that is, in the home, where they could be good wives and mothers.

There were even supposed medical arguments. It was recommended that women not play because they’re at risk of suffering blows to their uterus and breasts, which could compromise their fertility and lactation.

One new story published in 1961 in one of the largest newspapers in Brazil said this: “Women have more delicate bones, less muscle mass, oblique hips, abdomens which are longer and thus less resistant, lower centers of gravity, smaller hearts, fewer red blood cells, respiration which is less suited to the practice of intense sports, less resistance in terms of their nerves and natural adaptation.”

Andrea believes that the ban is the root of those prejudices and the difficulties that women who want to play still face.

[Andrea]: Às vezes eu acho que os próprios pais não deixam as meninas jogarem por terem esse preconceito.

[Irene]: She believes that many parents don’t let their daughters play because of this preconceived notion that was created decades ago.

That authoritarian view of women’s civil rights prevailed during the 21 years of the military dictatorship in the country between 1964 and 1985.

[Léa Campos]: We played wherever we could, in the street, in vacant lots. But since playing was banned, the police were always there to catch you.

[Irene]: This is Léa Campos, the first woman to be invited to serve as a referee in a FIFA match in 1971. My colleague Cláudia Jardim called her on the phone to learn what women who wanted to play did during that time.

Léa told her that she would meet up with a group of girls. They would play informal matches and during those matches…

[Léa]: I knew the police were coming because I heard the military police’s siren.

[Irene]: And when she heard the siren, she told the other girls to run and the police would arrest Léa.

[Léa]: They arrested me 15 times. And every time I said the same thing: “Podem me prender um milhão de vezes, e eu vou continuar fazendo lo mismo”.

[Irene]: And it was during those detentions that Léa became aware of a very important technicality. The ban was clear: women couldn’t play soccer…

[Léa]: But it didn’t say anything at all about being a referee. And that’s what I was interested in. I wanted to conduct the orchestra. I wasn’t interested in being a musician in the orchestra.

[Irene]: And she did it. Léa Campos was made a referee in the early ‘70s.

A bus accident that left her in a wheelchair ended her career in 1974. And her struggle became somewhat isolated. The ban finally ended in 1979 when the amnesty law was signed with the military government.

Let’s put this ban in context. While Brazilian men’s soccer won three world cups — in ‘58, ‘62, and ‘70 — and Brazilian soccer players were becoming global stars, more than half of the population was banned from playing the national game.

Even though the ban officially ended 40 years ago, obstacles remain.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Locutor]: Agora, agora, agora, agora, agora, agora, agora, gooool! Marta, um fenômeno mundial! Um fenômeno mundial!

[Irene]: Today Marta Viera de Silva is the most popular soccer player in Brazil, and one of the most well-known players in the world.

But long before becoming a global phenomenon, Marta was just a girl with exceptional talent, like Laura Pigatin.

In 1999, when she was 13, Marta was playing on a team in the city of Dois Riachos, in northeastern Brazil. Like Laura, Marta was the only girl who played on a boys’ team because there were no girls teams. Aside from being talented, she had the strength to ignore prejudiced comments, like that she was a “marimacha” [an anti-gay slur applied to women] and that soccer wasn’t for girls.

[Marta]: As pessoas falavam mal, chegavam para minha mãe e para meus irmãos e davam conselhos: “ah, não deixe ela no meio de um monte de meninos”.

[Irene]: Marta says that people said mean things about her and told her mom that she couldn’t leave her with a group of boys who weren’t going to respect her.

Marta told us that when she played in her first championship, she was the player who had scored the most goals and she was an essential part of her team. Marta also remembers that her talent bothered their opponents. So much so that the owner of an opposing team threatened to withdraw from the local tournament if Marta kept playing.

[Marta]: Eu fiquei super-frustrada naquele momento.

[Irene]: She was very frustrated and she had to leave the championship.

[Marta]: Não achava uma resposta do porquê disso tudo, né? Será que é tão complicado aceitar que um ser humano nasceu com talento, e sabe jogar e sabe fazer isso e é isso que te faz feliz?

[Irene]: And she couldn’t understand why it was so hard to accept that a human being who was born with talent couldn’t play and be happy. But she pursued her goal, which was to play for an important team.

Vasco de Gama, one of the big soccer clubs in Rio de Janeiro, was having tryouts to find new players. It was 2000 when Marta told her mom that she wanted to go to Rio de Janeiro.

[Marta]: Falei com a minha mãe e ela falou: “Ela não vai”. Tipo assim, ela não levou muito a sério…

[Irene]: Marta says that her mom told her: “You’re not going.” She didn’t take what Marta was saying seriously.

But Marta decided to do it anyway. She asked her closest friends and neighbors to lend her some money to buy the bus ticket. She barely had enough money to eat on the way. And were talking about a three-day journey from the northeast to the southeast of Brazil.

[Marta]: E aí tinha uns pontos estratégicos para parar, e tal, tomar café, fazer um lanche…

[Irene]: Marta says that while the bus stopped to let people get a coffee or have a snack, she had to watch every penny. She dealt with the hunger knowing that the little money she brought had to last her.

Marta tried out and made it on Vasco de Gama. Two years later, she moved to Belo Horizonte, and played on a local team. She was dedicated. She wanted to make soccer her life, but her options in Brazil weren’t very stable.

They still are. The greatest inequality in women’s professional soccer is financial. At the international level, a recent study by Sporting Intelligence — a website dedicated to sports news — shows the enormous gap between men and women’s salaries. According to the study, the contract that Neymar signed in 2017 for more than 30 million euros a year is equal to the salary of 1,693 women in major league women’s soccer in the world.

And that inequality becomes even more pronounced in Brazil, where women’s clubs don’t have the same level of financial support as in other parts of the world.

It was for precisely that reason that Marta decided to try her luck abroad. In 2004 she got a call from Europe. It was an invitation to go play with the Umea IK club, in Sweden.

[Marta]: Eu realmente acredito que eu vim para esse mundo para jogar futebol.

[Irene]: She says, “I really think that I was put on this Earth to play soccer.” She’s been playing professionally between Brazil, Europe, and the US for 19 years.

Despite the success Marta has had, the prejudices she faced still exist.

Let’s return to Laura Pigatin’s story.

In 2015, when Laura was 11, her team, ADESM, won a city championship and advanced to the next phase: the regional championship. But at that stage, the organizers of the tournament banned Laura from participating.

[Laura]: Ela falou que o campeonato era só masculino e que as meninas não podiam jogar e que se eu jogasse ela ia desclassificar o time, e nesse ano eu fiquei de fora.

[Irene]: Because the rules said that the tournament was just for men and that girls couldn’t play. And if Laura insisted, her team would be disqualified.

The strangest part is that, in the first phase of the championship, no one had been opposed to her playing.

[Laura]: Joguei de boa, todos os técnicos dos outros times aceitaram.

[Irene]: But when it made it to the Director of the Department of Sports, Leisure, and Youth of the State of São Paulo, the official in charge of the championship, she banned Laura from playing.

Rogério, her coach, pushed back. He tried to reason with the director.

[Rogério]: Na verdade é um regulamento machista né, que foi criado…

[Irene]: To get her to see that the rule was sexist and that it was still responding to the time when girls didn’t play soccer. But things are evolving, Rogério says, and they, the officials, are not evolving. They’re stuck in time.

Laura’s dad also spoke with the director.

[Lauro]: Ela seguiu o regulamento, mas faltou bom senso por parte dela de entender que era uma condição excepcional.

[Irene]: Despite the fact that the director was following the rules, to Lauro, she lacked common sense. She couldn’t understand that this was a special case. The director could have changed that rule to allow girls to play.

But neither Rogério nor he could convince her.

[Lauro]: Me senti realmente um Zé Ninguém, um idiota, me senti assim o pior dos homens.

[Irene]: That refusal, Lauro says, made him feel like an idiot, like the worst man.

And in the end, Laura wasn’t able to go with her team.

Andrea remembers how sad Laura was seeing her team from the stands.

[Andrea]: Ela ficava na arquibancada assistindo o jogo com olho cheio de lágrima.

[Irene]: With eyes full of tears.

The team lost the regional championship, and Laura was left thinking what would have happened if they had let her play.

The following year, 2016, Laura had another opportunity. Her team made it to the same championship, and the same director prevented her from playing again.

The frustration was too great for Laura’s father to bear

[Lauro]: Eu me senti um… me senti um merda pra falar a verdade.

[Irene]: He felt like shit, he says, so he vented on Facebook. Lauro’s feeling of frustration started a movement online to collect signatures demanding that girls be allowed to play in men’s tournaments.

The petition to allow Laura to play started making the rounds on social media. “Girls can play” was the slogan. And to everyone’s surprise, the response was huge.

The campaign started getting national attention.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Reportera 1]: Uma história que parou o Brasil. Muita gente não se conformou ao ver a desigualdade no mundo da bola.

[Reportera 2]: O caso da Laurinha gerou comoção nacional. Ela continuou jogando com os meninos.

[Irene]: Despite her shyness, Laura appeared on several TV shows, and on each one, she asked for the same thing.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Laura]: E agora que ia jogar a fase mais importante do campeonato não ia poder jogar.

[Animadora]: Não seria justo, né. Pô, não seria justo.

[Laura]: Só porque eu era menina, só.

[Irene]: For them to change the rules so that girls could play.

More than 11,000 people signed the petition that circulated on the internet.

The pressure from the public was so great that this time the director gave in and gave Laura permission to play in the regional phase of the championship.

But, for Lauro, it was a partial victory.

[Lauro]: Para a gente a vitória seria se eles tivessem falado assim, nós vamos mexer no regulamento e todas as meninas que quiserem.

[Irene]: A real victory would have been changing the rule to allow all girls to play.

But Laura’s participation that year was an exception. The rules stayed the same. Officially, the championship still does not allow girls to play on boys’ teams.

[Laura]: Não era por minha causa, né, que a gente estava brigando, era por todas as meninas, né?

[Irene]: Laura explains that this isn’t an individual battle. Her fight was to at least get men’s tournaments to admit co-ed teams.

The decree that made soccer an illegal sport for women ended officially in 1979. Twenty years later, Marta was banned from playing when she was still a teenager. That same thing happened to Laura just three years ago.

So, what needs to be done for girls to be able to play?

In an open letter published in 2017 in The Player’s Tribune, Marta thought back on her own career and, in a way, answered that question.

Cláudia and I visited Marta in the locker room of the Orlando Pride, her team, in 2017. And when we spoke with her, Marta read the letter to us.

[Marta]: Querida Marta de 14 anos de idade…

[Irene]: It was a letter addressed to herself, the 14-year-old Marta, that is, the Marta who took the bus that brought her from her small town to Rio de Janeiro.

[Marta]: Entre no ônibus. Eu sei o que você está pensando. Eu sei o que você está sentido. Não pense nisso.

[Irene]: In the letter, Marta tells the girl to get on the bus, that she knows what 14-year-old Marta is thinking, what she’s feeling and she tells her not to worry about that.

And a little after she starts reading, she stops herself.

[Marta]: É difícil ler essa carta porque… é difícil porque todas as vezes que eu li ela, me emociono, porque parece que foi muito mais difícil do que foi naquela época.

[Irene]: And she explains that it’s difficult to read that letter because she remembers that her path was tougher than it seemed at the time.

After taking a moment, she continues:

[Marta]: No quanto todo mundo disse que você não podia fazer isso, que você não deveria fazer isso.

[Irene]: And she remembers that people told her she wasn’t going to make it. That she shouldn’t even try.

[Marta]: Este ônibus te levará para realizar o seu sonho, o sonho de se tornar uma jogadora de futebol profissional.

[Irene]: That’s why she asks 14-year-old Marta not to give up.

Even though she’s writing to herself, Marta’s letter is also directed at Laura and all the girls who want to play soccer. It’s a way of asking them not to give up, despite all the obstacles that are still in their way.

[Daniel]: Laura is 16 now and she plays on a team with girls her age. It’s a team in the interior of the state of São Paulo: Ferroviária de Araraquara, one of the few teams that takes women’s soccer seriously. To train with them, Laura needs to travel for two hours, three times a week.

Despite being one of the youngest in the group, Laura made it on the list of headline players with Ferroviária and competed in the first under-18 Brazilian women’s championship, a tournament that started very recently in 2019 by the Brazilian Soccer Federation.

FIFA has also put in place new initiatives to form more professional women’s teams, even in Brazil, so girls like Laura can have somewhere to play as adults.

Irene and Cláudia Jardim are reporters. Irene is a reporter with The Correspondent and she lives between Italy and Argentina. Cláudia lives in Bangkok.

Mariangela Maturi also contributed to this reporting, which is part of “A Girls’ Game,” a journalism project produced with the support of the European Journalism Centre. “A Girls’ Game” was released in several languages, including Spanish, and also in different formats, with a nearly half-hour documentary. For more information, you can visit www.agirlsgame.net. We’d like to thank the Orlando Pride, Aguinaldo Suarez Fabiano Farah, the Pigatin family, Dibradoras, and Sandovaldo Euclides.

This story was edited by Luis Trelles, Camila Segura and by me. The mixing and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

Thank you to Sabrina Duque for her help and for reviewing the translation of the audio in Portuguese.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Victoria Estrada, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Luis Fernando Vargas. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Every Friday, we send out an email with recommendations for the weekend. It’s a simple format: five members of our team recommend something that inspires them — TV series, podcasts, books, music. We have fun putting it together and we think you’re going to like it. If you want to subscribe, go to radioambulante.org/correo. Again that’s radioambulante.org/correo.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

In the next episode of Radio Ambulante, it takes a lot of courage to reveal who you really are.

[Andrés]: She was the one who told me: “I know there’s something you don’t want to tell me, but there’s something you want to say.”

[Lucía]: I never imagined that in my nearly perfect home I would have something like that, which was outside of my preconceived notions.

[Daniel]: And there are those who would rather punish that honesty than accept you just as you are. That story, next week.