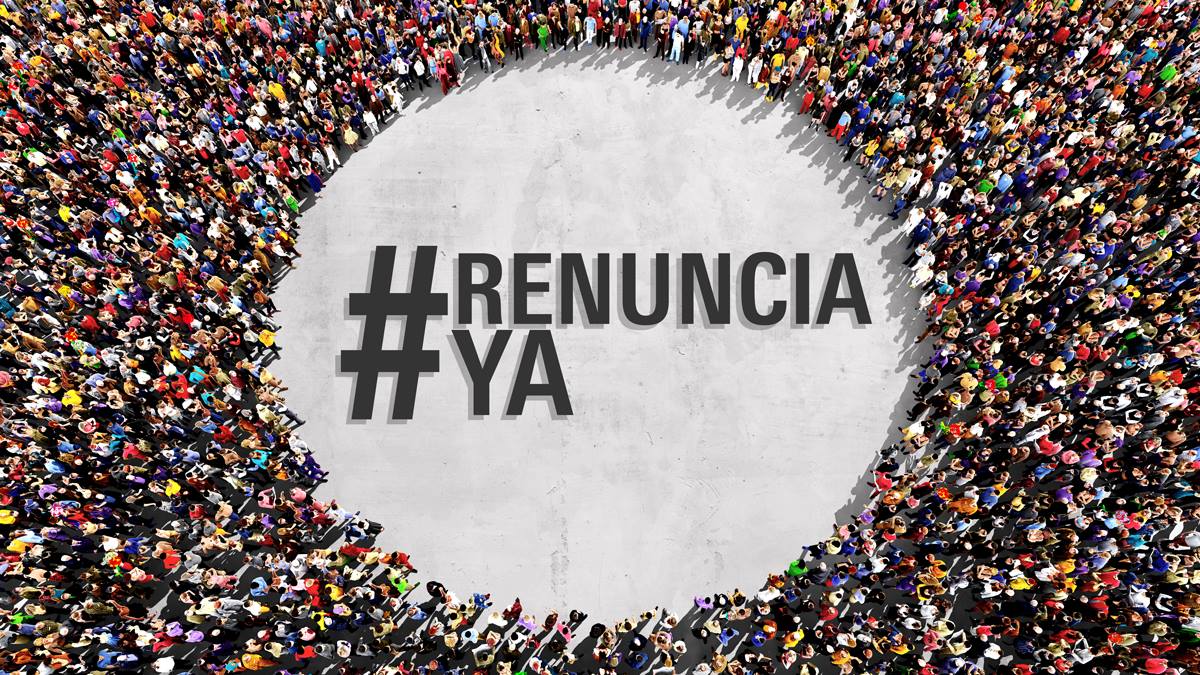

Translation: #RenunciaYa

Share:

Radio Ambulante is supported by the Sara & Evan Williams Foundation, and Panta Rhea.

Thanks also to our sponsor, MailChimp. Over 7 million people and businesses worldwide use MailChimp to send emails and newsletters. Radio Ambulante, by the way, is one of them. To learn more, visit mailchimp.com.

And thanks to Squarespace. Start building your website today at Squarespace.com. It’s an intuitive platform that is easy to use. Modern templates that look just as good on mobile screens or on a computer. Use the code ambulante at checkout to get 10% off. Squarespace –Your new website awaits.

—

Daniel Alarcón: Before today’s episode, we want to ask two small favors. First: Last year we launched a survey to better understand our audience, and it was really useful. Now we want to know a little more. We do this show for you, and to make it better, we want to know who you are. Please, take a few minutes to complete the second part. The link is on our website, radioambulante.org.

Second, if you like this show, please share it with your friends, your partner, or with a family member…Share the link to this episode or to our website; show someone how to listen to a podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, or the app of your choice. Growing our audience is the best way to ensure the future of this project. Thank you!

Okay, on with the show.

—

Newscast: With shouts of “Renuncia Ya” -resign now- thousands of people marched this Thursday in the Guatemalan capital and in other districts to demand the removal of President Otto Pérez Molina.

Daniel Alarcón: You’ve probably already heard the recent news from Guatemala. President Otto Pérez Molina resigned on September 2nd, 2015, after a series of protests that filled the streets of the capital. More than 100 thousand people showed up to protest on August 27th. And perhaps the most surprising thing is this: only hours after his resignation, the ex-president, was in jail.

It was a historic moment, above all for Guatemala, of course, where there is a long list of corrupt government officials, and almost all of them get away with it.

But this time was different. People went out into the streets and didn’t stop protesting for 5 months. No one expected the movement to make it this far, not even the person that started it.

Lucía Mendizábal: When we started the event, I didn’t have the slightest idea that it was going to be so big. I thought maybe 50 or 100 people were going to accept the invitation, and with that I was going to be satisfied.

Daniel Alarcón: This is Lucía Mendizábal, the organizer of the first anti-government protest on April 25th. Back then, the accusations against President Pérez Molina were widely known, were read about in the press; international investigators and even state prosecutors had already been following a trail that traced back to a corruption ring within the government. I mention this because, obviously, one protest by itself doesn’t bring down a president. But it’s also true that without the mass mobilization of citizens, without that pressure in the streets, it’s hard to see how the president would’ve resigned. And it started, like a lot of things these days, with social media.

Welcome to Radio Ambulante, I’m Daniel Alarcón. Today, we’re going back to the start of this movement. From Guatemala, Luis Trelles tells the story.

Luis Trelles: When Otto Pérez Molina won the Guatemalan presidency in 2011, the message he brought was clear: he was going to be president with a “firm hand” against corruption. It wasn’t for nothing: the previous three administrations had had one scandal after another. Fraud, money laundering, bribes…

Corruption became so common in the country, that an often repeated joke is that the motto for politicians tends to be, “The shame goes away, but the pisto–that is to say, the money–stays.” But Lucía isn’t laughing.

Lucía Mendizábal: Because it’s not just the controversy over them stealing money. Yes, that’s bad, but worse are all of the implications that has. Like the hospitals without medicine that are about to close down and the children dying of hunger. It’s a complete and utter mess. And constantly pushing us to pay more and more taxes because tax revenue goals were not met.

Luis Trelles: Lucía doesn’t look like a revolutionary. She’s a 53-year-old Guatemalan woman with a husband, two daughters and a small real-estate business. A citizen, like many others, that was sick of the corruption in Guatemala.

She told me that she didn’t expect much from Otto Pérez Molina. But all of the rage she had built up after years of impunity for corrupt government officials in her country, exploded in April of this year, when the news of La Línea came out.

Newscast: Breaking news surprising a lot of people. Various members of Guatemala’s Tax Administration were arrested by the Attorney General because they were apparently involved in a tax fraud ring.

Luis Trelles: It was a customs corruption scheme. Some officials weren’t collecting import taxes in exchange for bribes that amounted to millions of dollars. Eventually, more than 40 government workers were charged with being involved in the scheme.

Even worse, there was evidence that the personal secretary of Vice President Roxana Baldetti was the one giving orders. The image of a “firm hand” that Otto Pérez Molina had promised–already damaged by previous scandals–now seemed to be completely vanishing.

The elections were five months away, in September, and many people were talking about leaving blank ballots to show their discontent. That’s why on that night, when Lucía found out about the “La Línea” scandal, her first reaction was to write the following post on Facebook:

Lucía Mendizábal: “Let’s see if all these people talking about not voting, instead of talking about not voting, go out into the streets to protest.”

Luis Trelles: It seems like the typical venting that takes place on social media, the kind that receives a ‘like’ and then disappears forever. But the next morning Lucía looked over the comments.

Lucía Mendizábal: I saw that there were people saying to me, “Sure, when? What time?” And I was like, “Oh, now what?”

Luis Trelles: The only thing that occurred to her was to organize a protest through Facebook for April 18th, two days later.

Lucía Mendizábal: That was the first time I had made a public event, to bring together the people that wanted to be a part of it, that weren’t necessarily my friends.

Luis Trelles: And that’s because there is a very Guatemalan trait that affects things when it’s time to protest: embarrassment or shame. In fact, in Guatemala, it’s difficult to go an entire day without hearing phrases such as this one:

Lucía Mendizábal: “Don’t be embarrassed,” “come in, don’t be ashamed” “how embarrassing.” We have a culture where everything embarrases us. And well, that carries over when it comes to fighting for our rights. We’re embarrassed to fight for our rights because who knows what others are going to say.

Luis Trelles: For that reason, Lucía was really surprised when she realized that 600 people had confirmed their attendance for the march in less than 24 hours.

Lucía Mendizábal: I said, “Wow, 600 people are coming to protest!” I couldn’t believe it. It was really emotional, really…I don’t know, it was amazing.

Luis Trelles: It seemed like the protest really was going to happen. So Lucía sought help. The son of a good friend, Gabriel, 36 years old, was more experienced when it came to using social media and agreed to help her. The first thing he did was change the name of the event.

Lucía Mendizábal: Ah, because the rally was called “Peaceful Protest to Ask for the Resignation of Roxana Baldetti.” But Gabriel said, “This isn’t going to catch on, people are not going to remember it.” Let’s use ‘Resign Now’ instead since it’s shorter and it’ll catch on and people will remember it.”

Luis Trelles: Gabriel called a friend that was a graphic designer so that he could make a logo with the text #RenunciaYa. They also decided to change the date of the protest. They made it for April 25th, one week after having created the event on Facebook, so that they had more time to organize themselves. It was going to be at the Plaza de la Constitución, right in front of the Palacio Nacional.

Three days later, the event had grown. A lot. Four thousand people had already confirmed their attendance through Facebook. A local newspaper had published the invite and other organized movements adopted the hashtag and shared it through social media. That helped the event grow very quickly.

It’s worth noting that Lucía isn’t a political leader. She had simply spent a lot of time on the internet complaining about the government. Now that she had to coordinate a rally of thousands of people, she was panicking. So she decided to expand the team.

She recruited a diverse group: three women around Lucía’s age and four younger people between 20 and 36 years old. Some of them were friends of Lucía or of her daughters, and she had met the others because of what they had written criticizing the government.

Meanwhile, on Facebook, political parties were starting to ask Lucía questions.

Lucía Mendizábal: “So, do you want us to bring a bus full of people?” And we were like, “No, we want people to just come.” Nothing more.

Luis Trelles: Here is another thing you have to understand: Guatemala is a country–like many others in Latin America–where politics and money go hand in hand, even when it comes to protests. They organize protests regularly, but sometimes there’s a political party that pays protesters, whether it be with money or food. And that was something that the group behind Renuncia Ya absolutely wanted to avoid.

To remove any doubts, the group released a statement. They clarified that they weren’t linked to any political party, and moreover, the protest had to be totally peaceful.

Lucía Mendizábal: We didn’t want anyone to start breaking windows, leaving graffiti, or anything that people expected from us, being one of the most violent countries in the world. What we were going to do was to make noise with pots or whistles or whatever we had on hand, sing the national anthem and go home.

Luis Trelles: There was less than a week before the protest and every day more news came out that connected Vice President Baldetti to the La Línea scandal. People became angrier and Lucía started to worry about some of the provocative comments on the Facebook event page.

Lucía Mendizábal: Saying things like “yes, we have to start throwing rocks because this can only be solved with bloodshed…” trying to scare people and stop them from participating, because there were going to be a lot of people there doing bad things.

Luis Trelles: Lucía did some research and realized that the people leaving these comments had relatively new accounts, many of them didn’t even have a profile picture, and they were only friends with each other. She connected the dots and remembered the news that had come out in 2014. The Communications Undersecretary had revealed that on the 13th floor of the Guatemalan Institute for Tourism, there was a call center dedicated to monitoring social media networks and leaving comments in support of the government.

Lucía Mendizábal: So it’s not that I have evidence, but I’m saying if it walks like a duck and goes quack, quack, it has to be a duck.

Luis Trelles: Lucía decided to respond directly to them.

Lucía Mendizábal: So I told them, “Good evening 13th floor! So happy you could join us!”

Luis Trelles: After that, the more aggressive comments started to go away. Lucía calmed down, but not quite all the way. The protests she remembers when she was younger usually ended poorly. It wasn’t out of the ordinary for students and community leaders to die in confrontations with the police.

Protester: And everyone was told to pray to God, because in that moment, they were going to kill them…

Luis Trelles: This was during the 70s and 80s when the country was in the middle of a bloody civil war. The army killed thousands of indigenous people.

Indigenous Woman: They came to our communities, gather us up, separate the men and the women…

Luis Trelles: In fact, President Otto Pérez Molina was an army commander during the war. You have to remember that in 2013 a Guatemalan court concluded that the army had committed genocide.

The Renuncia Ya team had done everything it could to coordinate a peaceful demonstration, but they didn’t really know what to expect. When April 25th finally arrived, the event had grown to the extent that 30 thousand people had confirmed their attendance.

Lucía Mendizábal: We arrived at the park like any other person headed there. Nobody knew who we were or what part we had played or anything. And it was really exciting to see how the park kept filling with more and more people.

Protester: “They are breaking the law and doing whatever they want.” “How can it be that they are robbing us when there are people dying of hunger. It’s really disappointing. Resign now!”

Luis Trelles: In the end, 32 thousand people showed up and stayed there late into the night. There were students, workers, indigenous groups, LGBT groups, in short, all kinds. The protest was open and every group came with its own set of claims, but they were united for the same reason: to demand the resignation of Vice President Roxana Baldetti.

Lucía Mendizábal: And given the opportunity, everyone came out. They told us the middle class was the majority and that’s important because supposedly in Guatemala’s entire history, the middle class had never gone out to protest. It was always the less privileged class that went out to protest.

Luis Trelles: The next day, Lucía met up with the rest of the organizers and they all felt the same way:

Lucía Mendizábal: Because we were really flying high, and with that ego, well, who knows how high it went up. And little by little, we had to get back to where our feet touched the ground and realize that it was not just one person. It was the people that were here. When one took a step forward, the others followed because they were waiting for someone to take that first step.

Luis Trelles: They decided to organize another protest for three weeks later. But everything moved a lot faster than they had anticipated.

News Bulletin: Guatemala’s Vice President Roxana Baldetti has resigned after an investigation of her alleged participation in a customs corruption ring that has sent more than 20 people to prison.

Lucía Mendizábal: Everybody went to the park to celebrate and to set off fireworks, to sing and dance out of joy because they managed to force Roxana Baldetti’s resignation.

Luis Trelles: The newspaper El Periodico had spent a lot of time pointing out the Vice President’s scandals. The International Commission against Corruption and Impunity in Guatemala, a UN body known as the CICIG, had joined the Attorney General’s prosecutors to investigate the La Línea case and Baldetti.

Without that work, the protest held in April wouldn’t have gone much further. Lucía is the first to recognize that Renuncia Ya played a small part in Baldetti’s resignation.

Lucía Mendizábal: There are a lot of factors here, and if we wanted to say, “She resigned because of the protests,” we would be lying. We would be lying to ourselves.

Luis Trelles: The group achieved what it had wanted. Maybe the timing was right to disband. But they came to another conclusion:

Lucía Mendizábal: Well, if Roxana had already resigned, now Otto should resign.

Luis Trelles: They had called for a second protest–scheduled for May 16h–and that was still on. This time, groups from the country’s interior joined. Those who lived in provinces further out and couldn’t make it to the city to protest, opened their own calls on Facebook.

Lucía Mendizábal: We started to collaborate with the organizers and named them, for example, “Renuncia ya Jutiapa,” and gave them a picture they could upload for their call. And then, just like that, we said, “We have another franchise now.”

Luis Trelles: Lucía and the other collaborators had created a movement that was open and transparent. For that reason, it easily went viral. But that also had its disadvantages. After the first protest, groups started to appear on Facebook and other websites that used the image of Renuncia Ya, but that were completely fake.

Lucía never knew who was behind these pages, but suspected that they were people that wanted to take advantage of Renuncia Ya’s popularity to start their own political party.

Lucía Mendizábal: Well, it makes me upset. It makes me get really angry when other people want to pose as something they are not. Because for us it was important that there were no political gains for anybody. That’s to say, we recognize that new political parties are emerging, but we don’t want anyone to do it under false pretenses from the beginning.

Luis Trelles: But the fake pages weren’t the only problem. There started to be divisions within the original group. There were two generations: on one side, there were the “patojos” (children) as Lucía calls them. They were the four younger people between 20 and 36 years old that were more prone to taking risks. On the other side, there were Lucía and her two 50-something-year-old friends. One of them was worried about the reprisals that they would be facing from the government. She wanted to leave the movement and that made the others think about whether they should leave as well.

Lucía Mendizábal: Because either we were all in or we went our separate ways.

Luis Trelles: Lucía was also worried. But before deciding whether or not to dissolve the group, they wanted to go through with the protest on May 16th.

She didn’t know what to expect this time either. After all, Vice President Baldetti had already resigned and they were asking themselves if there were still people willing to go out into the street to demand the resignation of the president. To top it all off, the day of the protest…

Lucía Mendizábal: It rained cats and dogs, and everybody caught in the rain was soaked from head to toe. I wasn’t prepared and I got soaked, my shoes were going “clotch, clotch” while I was walking.

Luis Trelles: But despite the rain, the protest was even bigger. 60 thousand people came to the square.

Lucía Mendizábal: It was cramped. Even moving around was difficult. Let’s remember that the expectation was always for 50.

Luis Trelles: The May 16th protest was the last event organized by Lucía. After that, the original Renuncia Ya group was dissolved. But the movement continued. For four months there were protests almost every weekend in front of the Palacio Nacional. Some of them were bigger than others, but the pressure from citizens didn’t stop.

The younger members of the original group that Lucía had founded continued working under a new hashtag: “Justicia Ya” (Justice Now).

The last straw was a general strike organized for August 27th. More than 100 thousand people returned to the Plaza de la Constitución with a new slogan: “I don’t have a president.” Many of them carried banners and posters with the slogan that had started it all: Renuncia Ya.

And five days after that massive demonstration, this happened:

News bulletin: Guatemala awakes without a president. The until then-president Otto Pérez Molina resigned hours after a judge issued an arrest warrant against him for his alleged involvement in the “La Línea” case of customs corruption.

Luis Trelles: Otto Pérez Molina resigned on September 2nd, after Congress had taken away his immunity, and that same day he went from the presidency to jail.

Newscast: There was unrest between the press and police when ex-President Otto Pérez Molina was taken to Matamoros prison. The arrest was to remand him in custody.

Luis Trelles: Although the original Renuncia Ya crew had dissolved, Lucía continued protesting at the demonstrations. She went back to taking care of her family and her business, and continued fiercely commenting on the country’s politics using her Facebook account, as usual. Even today she’s convinced that nothing she did was special.

Lucía Mendizábal: It’s like one of those cartoons where someone strikes a match and when it lights there’s a little room full of dynamite, and I feel like the same thing happened to me. I said, “Let’s go protest” and a lot of people said, “Yeah, let’s go, when?” and since it was me, or rather when I said, “Let’s go”, I felt compelled to tell them when, at what time, and where.

Luis Trelles: But what began as venting on social media has grown in many ways. Renuncia Ya and Justicia Ya have become slogans in other Central American countries. In Honduras, the protests organized with these mottos have attracted thousands of people.

They are already talking about a Guatemalan Spring. And it’s true that the protesters achieved what they wanted and did it in a way that hadn’t been seen before. Videos of the protests are moving because of the massive crowds of people that came together at the country’s central square. In one of the videos during the general strike, you can see a student with a simple handwritten sign that represents perfectly the crossroads that Guatemala is facing right now. Her sign reads: “It doesn’t matter if he resigns if the laws don’t change.”

Luis Trelles is a producer for Radio Ambulante and lives in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The first round of Guatemalan elections was held on September 7th. Jimmy Morales, a comedian with a long career on local television, is leading. The final round to elect the next president will be on October 25th.

Luis Trelles used the studios of Producciones Cabeza in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico.

We would like to thank Rafa Mora, Álvaro Montenegro, and Gabriel Carrera for their help. We are also thankful for the help of Ingrid Sub Cuc de Sobrevivencia Cultural and William López of the International Center for Journalists.

Camila Segura is our Senior Editor.

Martina Castro is our Senior Producer.

Silvia Viñas is a producer and editor for Radio Ambulante.

The rest of the team includes Clara González Sueyro, David Pastor, David Leonard, Barbara Sawhill, Alejandra Quintero Nonsoque, Claire Mullen, Diana Buendía, and Dennis Maxwell. Our executive director is Carolina Guerrero.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. To hear more, visit our website radioambulante.org

I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thank you for listening.