The Bat Man | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at Lupa.app.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Pre-Roll Deambulantes]

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Some people discover their calling in their teen years, others later down the road. But there are those who seem to have it clear from the moment they start talking…

[Rodrigo Medellín]: My first word was not mom, not dad, not poop. My first word was flamingo.

[Daniel]: This is Rodrigo Medellín, a scientist and researcher at the Institute of Ecology of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM. He is 64 years old, but ever since childhood…

[Rodrigo]: I started having an interest in the animals that I saw in books, on TV, every Christmas, every birthday: “And what does little Rodrigo want?” Well, books about animals. “And where does little Rodrigo want to go?” Go to the zoo, or to the countryside to see animals. Always, all my life…

[Daniel]: He grew up in Mexico City, and over time he studied more and more about animals. Mammals were his favorites. He could answer any question about them. Back then, in the late 60s, there was a very famous television show that Rodrigo used to watch with his mother.

[Rodrigo]: There was a show on Mexican television called The 64-Thousand-Peso Grand Prize.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Man]: The 64-Thousand-Peso Grand Prize. The show with the highest cultural standards on radio and television in Mexico.

[Daniel]: It was very popular, hosted by the then equally famous Pedro Ferriz Santa Cruz. The contestants had to master some subject, whatever it was—a book, sports teams, history—as long as they were experts. And the host challenged them with questions. If they answered correctly, they won more and more money until, after several questions, they reached the jackpot. For example, this contestant was an expert on Don Quixote de la Mancha…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Pedro Ferriz]: Now we come to the end. For the grand prize of 64,000 pesos… tell us who Don Quixote left as executors…

[Contestant]: Graduate Sansón Carrasco and the priest…

[Pedro]: Correct! (Music and applause).

[Daniel]: One of those evenings, when Rodrigo was 11 years old, he was in his living room watching the show with his mother:

[Rodrigo]: And I tell my mom, “Well, I… I want… I want to compete there, I want to be a contestant, and they can ask me about mammals because I can answer anything.”

[Daniel]: His mother’s initial reaction was to tell him that he was just a boy, that he had better go back to his games. But Rodrigo was so insistent that she had no choice but to contact the producers. She told them that her eleven-year-old son wanted to participate in the show. But they were not so enthusiastic about the idea; they told her:

[Rodrigo]: “Look, this is a show for people who have a lot of knowledge in their heads. It’s not for a kid to catch a ball and hit something and win a prize. It’s for someone who has knowledge and is going to show it in front of the television cameras.” So my mother said to them, “Well, ask the child, and see whether he has any knowledge.”

[Daniel]: They got a book on animals and asked Rodrigo a list of questions. At first they were simple questions, “Are there monkeys in Mexico? Where do lions live?”

[Rodrigo]: I mean, they expected me to say, maybe, Africa. But I also said, “It’s sub-Saharan Africa. And then there’s also a population in India, and it’s a different subspecies,” and so on.

[Daniel]: He answered all the questions.

[Rodrigo]: Well, they immediately said, “Hey, congratulations because you are going to be the first kid on the show.”

[Daniel]: Rodrigo was prepared to give the best of himself in the contest. The day came. It was a Saturday. Unfortunately, there are no records of that recording because they were lost in the ‘85 earthquake along with much more archive material.

But he remembers that they began with simple questions for a nature lover like him. “For 64 pesos, what are the different primate suborders? For 128 pesos, what are the scientific names of the five big cats…?” Rodrigo had answered 10 questions correctly and got up to 32 thousand pesos, about 400 dollars at the time. There was just one question remaining. And if he answered it correctly, he would double the sum and keep the grand prize of 64 thousand.

[Rodrigo]: I have it tattooed with fire on my brain. I was asked for six diagnostic characteristics of mammals. No, not exclusive to mammals, but diagnostic of mammals.

[Daniel]: That is, those that characterize one species from another when performing a scientific classification. That last answer eluded him. It was too technical for Rodrigo’s level of knowledge at the time.

[Rodrigo]: And then when you lose, they don’t give you thirty-two thousand pesos; they give you a consolation prize, which in my case was a Mabe stove. What is a kid going to do with a Mabe stove? A Mabe stove that was valued at the time at 4 thousand pesos? So my mom said, “Well, well, I’m going to sell the stove and I’m going to give the money to the boy.” And what did I do with that money? I bought a lot of fish tanks and put tropical fish all over the house.

[Daniel]: He didn’t know it at the time, but in addition to his tropical fish there was another big prize, and he had already earned it.

We’ll be back after a break.

[Wise]: This message comes from NPR sponsor, Wise, the universal account that lets you send, spend and receive money internationally. With one account for over 50 currencies, who exactly is Wise made for? It’s made for Austrians in Australia. South Africans in Sweden. It’s made for New Delhi, New York and even regular York. When you use Wise to manage your money across borders, you always get the mid-market exchange rate, with no markups and no hidden fees. Learn more at Wise.com/npr

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Fernanda Guzmán, picks up the story. This is Fernanda:

[Fernanda Guzmán]: Since Mexican television had no more than three channels at the time, and this show was the one with the highest rating, according to Rodrigo, everyone was watching.

[Rodrigo]: Including the dean of Mammal Studies in Mexico.

[Fernanda]: Dr. Bernardo Villa, professor and researcher at UNAM, who died in 2006, was very impressed to see a child with so much knowledge about mammals, so he decided to call the channel to get Rodrigo’s phone number and contact him. When he called him, he said:

[Rodrigo]: “Hey, well, I see that you are very interested in mammals. Why don’t you come to the UNAM Institute of Biology? And we’ll take you out to the field, we’ll teach you about mammals seriously, and you will be able to learn from the animals that interest you so much.” Well, that was a dream come true for an 11-year-old boy, wasn’t it?

[Fernanda]: His mother took him to the Institute of Biology, and there Dr. Bernardo Villa greeted him very cordially. They shook hands and then he introduced him to the rest of his team. Rodrigo soon aroused a lot of curiosity and became a small celebrity within the Institute.

[Rodrigo]: The other researchers are there watching. “And that boy… and that boy, what is he doing here? That…? Where did he come from?”

[Fernanda]: One of the first things Rodrigo saw in the Institute were some dissected animals that were arranged near the entrance. They seemed prepared for a museum. He had already seen one of them in his books. In Mexico it is known as tlacuache, that is, the common opossum. It also has names like calatrupa or carachupa.

[Rodrigo]: And so I see it, I recognize it right away, I identify it and I say, “Oh, that’s a cayopollín,” and all the others burst out laughing. “It’s a what? A cayo what? What did you say? Where did you get that?” “No, well, from such and such book, I don’t know.”

[Fernanda]: The common names given to animals vary greatly because they depend on the idioms of each region. And Rodrigo’s childhood books were from an Argentinean encyclopedia called “The World of Animals,” so he knew many by their Argentinean names, which sometimes did not match the Mexican ones.

[Rodrigo]: “From now on, you are the cayopollín.” And then everyone to this day, the… the old professors who are still around still refer to me as a cayopollín.

[Fernanda]: After he received this new nickname, Dr. Villa took him to see the Institute’s scientific mammal collection. Rodrigo was fascinated by the enormous variety of his favorite animals. But do not imagine that it was like an exhibition of dissected animals in a museum. Scientific collections are more like a cabinet full of drawers that, when opened, have different species with their respective information.

Rodrigo and Doctor Villa continued talking for a bit, and at the end of the tour, the doctor asked him:

[Rodrigo]: “Well, then, what would you like to do?” I tell him, “No, well, whatever you want. I can help you with anything here.”

[Fernanda]: Since Rodrigo had liked the collection of mammals so much, Dr. Villa decided to use it to entrust him with his first task: they had a number of mammals preserved in a very large freezer, waiting to be prepared to for inclusion in the collection.

[Rodrigo]: He says to me, “So would you like to start preparing a… a mammal?” Well, of course.

[Fernanda]: I am going to explain the process to you, and note that it can be a bit disturbing. The animal needs to be frozen or have died very recently. You begin by making a superficial incision, cutting only the skin layer, from the chest to the groin. Then the arms and legs are broken so that you can peel off the skin of the animal in such a way that it is like a glove, which you can later stuff with cotton and close the incision.

Rodrigo began to work. That task lasted several days, and he enjoyed it from start to finish, preparing mice and other species of animals. That changed his daily routine…

[Rodrigo]: So, after school! Ruuuun! I would run, eat a sandwich on the way, and go to the Institute of Biology and start preparing there until 9, 10 at night, and then I would go home.

[Fernanda]: It was about an hour’s walk home. Those were different times and it was not dangerous for an eleven-year-old boy to walk alone. But it was a very heavy load for Rodrigo, and it was hard to juggle his homework and the Institute. With his passion for biology, he began to skip school without telling his parents, and his grades began to drop… But he always tried to pull both boats forward.

Over time, the Institute of Biology began granting him permission to go on excursions and capture some small species alive, so that he could take them home and observe them carefully. He fed them, examined their behavior, the schedules they followed to sleep and eat, the way they interacted with him…

[Rodrigo]: I started bringing home scorpions, tarantulas, snakes, bats, cacomistles, raccoons. Everything you can imagine. And my mom put up with me. I don’t understand how she put up with me.

[Fernanda]: Well, and his dad and his four brothers did too. Everyone put up with it because they saw how passionate Rodrigo was.

After a couple of weeks of observation, he would return to the place where he had taken the animal, and set it free. Years passed, and Rodrigo’s tasks at the Institute began to diversify. He started to examine clean skulls under the telescope and to learn taxonomy, the science that systematically classifies living organisms.

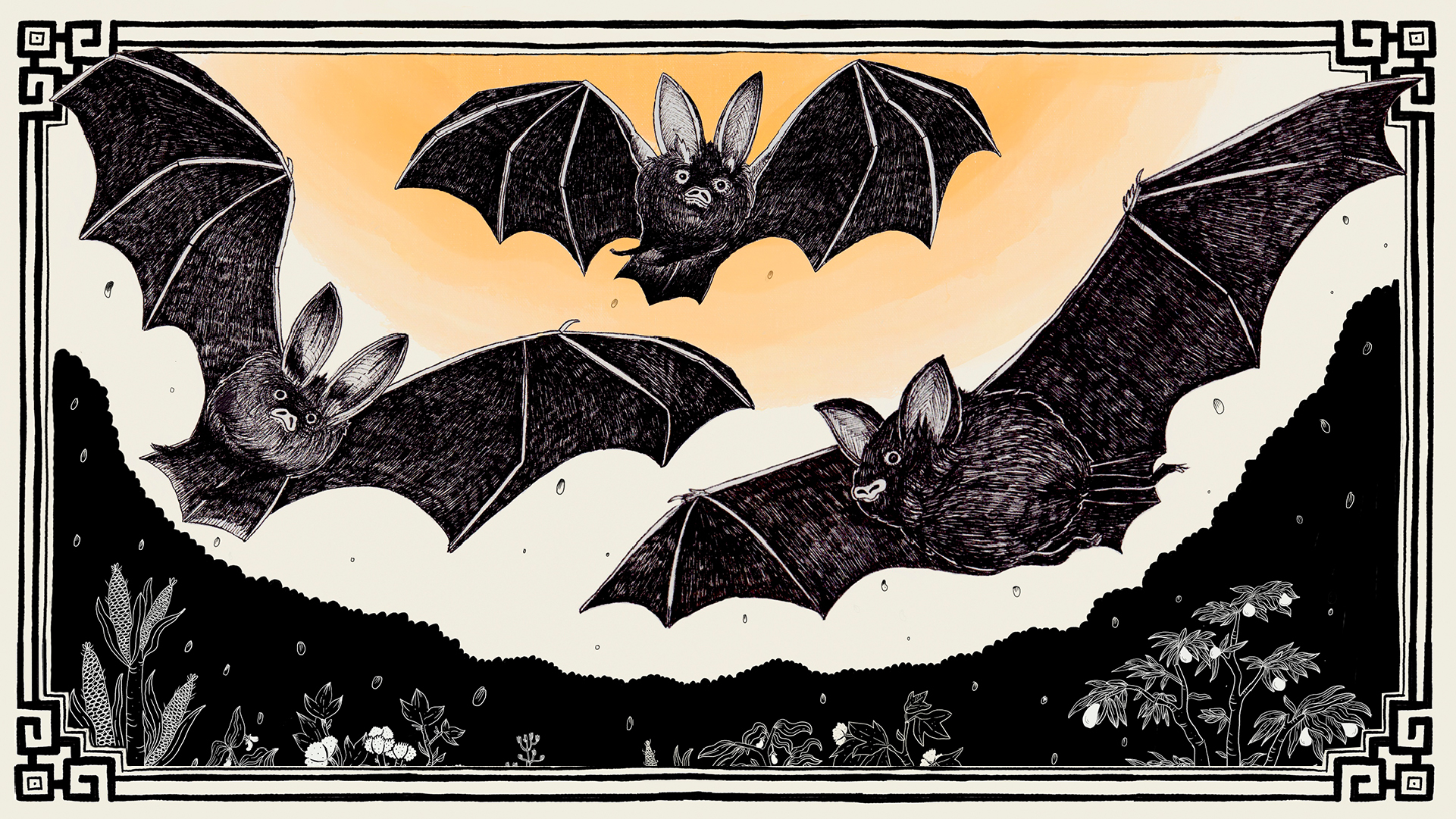

When Rodrigo started going on field trips, he would sneak out of school to accompany the biologists. On one of those trips they went to the cave of the Zopilote Canyon, in the state of Guerrero, a place that Rodrigo remembers fondly to this day because it would be the first time he would see up close the animal that would define much of his career…

[Rodrigo]: My first bat came into my hands when I was 13 years old. I was with a researcher from the Institute of Biology. We went into a cave and he grabbed a bat, put it in my hand, and said, “Let’s see what you see. Observe it and tell me what you see and how you think it lives.” Wow, well, I’m in shock.

[Fernanda]: He stared closely at the bat, that began to bite his gloved hand. Urine from the bats that were at the roof of the cave dripped on him. One drop hit him in the face and he felt an instant burning sensation. The smell of the place was penetrating, similar to ammonia. After observing the bat carefully, Rodrigo answered:

[Rodrigo]: “I see some very large ears, and I see a little beak on his nose. And I see that below where you grabbed him, well, there are a bunch of small wings, chapulines, grasshoppers, cockroach legs, things like that, so he must eat insects.” So he kept on asking me. And then he would take that one off my hands and give me another one, and then another one.

[Fernanda]: The bats the biologist put in Rodrigo’s hands were all of different species and fed on different sources: insects, fruits…

[Rodrigo]: We saw at least five species of bats, on that first day of my life, when I was submerged into the world of bats, right?

[Fernanda]: The details he learned about bats there captivated Rodrigo. From the beginning, he was struck by the fact that they all lived in the same cave despite being of different species. It was a small hook that piqued his curiosity. From that day on, he began to investigate everything about them.

Two years later, he was able to take some bats home temporarily. He shared a bathroom with his two brothers…

[Rodrigo]: I filled it with hematophagous bats, with vampire bats. Vampire bats living in your bathroom, I recommend that to you.

[Fernanda]: Hematophagous bats, or vampires, which, as you probably guessed, feed on blood.

[Rodrigo]: My brothers, to put it bluntly, started calling me all sorts of names… “Rodrigo, get those horrible animals out of there!” “No, I won’t take them out.” And there they stayed. And of course, you walked into that bathroom and it looked like a Hitchcock movie because it was splattered with blood on the walls.

[Fernanda]: But aside from the initial scare, his siblings accepted it. This is Alejandro, his older brother:

[Alejandro Medellín Legorreta]: We were getting used to having that kind of animals in the house. I even liked to see them, and Rodrigo, with that passion of his that he still has, told me, “Look, you see… those are his modified fingers, his wings…”

[Fernanda]: Like Rodrigo, he too had always liked animals. Although sometimes it was not the most convenient thing in the world to go in to take a bath and find an iguana in the shower, but…

[Alejandro]: Seeing him so passionate about it, so joyful, the happiness of being close to animals, inspires you, it’s infectious. And it is a passion that finally ends up being shared, you know?

[Fernanda]: One of the bats that Rodrigo brought home was somewhat weak. He got desperate and asked his older sister, who had studied medicine, for help: he asked her to draw some of his blood so that he could quickly feed the animal.

[Alejandro]: We said, “Are you crazy? What’s wrong with you?” And my sister drew blood from him with a syringe. Rodrigo put it in a soft-drink cap, opened the cage, put his blood inside, and the vampire went down to drink Rodrigo’s blood. And it was an… an amazing thing. I didn’t know that vampires drank blood like a puppy drinks water.

[Fernanda]: Of course, he couldn’t always rely on his own blood to feed the bats. To feed them daily, Rodrigo went to the veterinary school, where he filled a bucket with cow’s blood. But it is not as simple as putting it on a plate for them to drink. The blood coagulates quickly and becomes inedible to bats. To avoid this, Rodrigo had to beat the blood slowly with his hand, until some kind of floating layers were formed. He would remove them one by one, and then he would take that blood home.

[Rodrigo]: I took out the ice trays from my mom’s freezer. I threw out the ice. Then I replaced the ice with blood and put the ice trays back inside, (laughs) in the freezer. And then I would thaw one ice cube of blood per vampire per night and put them in little pewter boxes, like this.

[Fernanda]: When he walked into the bathroom with the blood cubes, the bats that were normally resting on the walls…

[Rodrigo]: They would jump and plop! They fell into the blood and plop! The blood splashed and then, of course, the walls were all splattered with blood.

[Fernanda]: But they also got out of the bathroom. Rodrigo and Alejandro remember one particular night well, when their parents were getting ready for bed. This is Alejandro:

[Alejandro]: My parents were there that night. And my mom tells my dad, “One of those black moths got inside. Take it out, please.” And my mom couldn’t see very well, she wasn’t wearing her glasses…

[Rodrigo]: The five bats circling around them (laughs). They were already in bed and everything. And my mom thinking they were one of those moths that get in… (laughs).

[Alejandro]: My dad turns around and says, “Rodrigo, go get your bat.” And my mom screamed and covered herself up to here with the sheets. And it was an incredible scream.

[Fernanda]: So, living with different animals became a common, everyday thing at home…

[Alejandro]: All kinds of problems with animals. “Rodrigo, your bat has escaped… Rodrigo, the viper… Rodrigo, the iguana and….”

[Fernanda]: But his mother couldn’t get used to the bats. At first, she was afraid of them, even a little disgusted. But Rodrigo came up with a way to make her look at them differently:

[Alejandro]: Once, he came home and that what when he finally brought mom on board about the bats, because he brought home a female bat with a suckling pup and said, “Look, mom, she is feeding it… her baby.” And we all thought it was very cute, you know?

[Fernanda]: Rodrigo and his family lived that way until he graduated from high school in 1979. That year, he was finally able to become an official student at the Institute of Biology.

He was still interested in the animal world in general, but the more he studied bats, the more his passion for them increased. A passion that for most of us can feel a bit strange. For example, the first time I saw a bat, I ran away frightened because I thought it would hurt me if it came near. I think I’m not alone in this; many other people see bats as threatening, even disgusting animals, like rats with wings.

This bad reputation they have comes from the Middle Ages, when they were associated with demons.

[Rodrigo]: Sent by the devil, used for witchcraft, all sorts of bad things, and they are going to give us diseases…

[Fernanda]: There is also the possible origin of the word vampire: the word “vampir” from Hungarian, which refers to a preternatural being with an evil nature, who seeks to feed by sucking the blood of sleeping people.

[Rodrigo]: A dead person who comes back to life at night and goes out looking for someone to suck blood from, but it has no link of any kind with the structure, with the shape of a little bat.

[Fernanda]: This figure was used by Bram Stoker when he published the famous book Dracula in 1897. In this book, the vampire can transform into different forms, and one of them is a bat. It’s a story that has been made into a movie several times, and in various ways. That association is already part of the culture, and it is inevitable to connect the vampire with a bat.

And well, we know it is true that there are bats that feed on blood, like the ones that Rodrigo had in his bathroom at home. The association is not so far-fetched. But in reality, of the more than one thousand species of bats that exist, only three are hematophagous. The rest feed on fruits, nectar, moths, flies, and other insects.

All this context has caused bats to be rejected out of fear, and this fear can put their survival at risk.

[Rodrigo]: The biggest threat affecting bats today is the destruction of their roosts, both intentional and unintentional.

[Fernanda]: There are well-intentioned people who try to interact with them because they’re curious, but if they’re not experienced, they can scare the bats and damage their roosts. And some others kill the bats to keep them away from their animals.

Urban sprawl is also a threat to bats. In Mexico, caves where bats lived have been dynamited and gassed in order to make way for constructions. Rodrigo got to know some of these places before they were destroyed, and when he visited them again, after the interventions…

[Rodrigo]: It is a terrible feeling of uneasiness. It is very sad. I mean, mainly because of the destruction caused to the bats and because people are no longer going to have the benefit of having the bats there, but also because part of my childhood has been destroyed.

[Fernanda]: One of the places Rodrigo refers to is the cave of Tequesquitengo, in the state of Morelos. It was a very deep cave and you could go down with the help of a safety rope. Some 100,000 bats flew up from the cave and it was a sight to see, a beautiful sight. But a construction company became interested in the area….

[Rodrigo]: They divided up that area and, well, that cave was simply filled with gravel. That was the end for 100 thousand bats. A really stupid thing, total nonsense.

[Fernanda]: Bats’ bad reputation made Rodrigo look at them with compassion. To him, they are the most mistreated animals in the world.

Ever since he held his first bat, Rodrigo set himself a purpose: part of his career was going to be devoted to defending them, trying to fight back that bad image. And to begin with, he had to study everything that was already written about this animal and continue going out into the field to continue developing new knowledge. He began an in-depth investigation, and the results helped him form the necessary arguments to start convincing people that bats are not dangerous. This would be the basis of his outreach effort to help.

[Rodrigo]: There are many animals that have a negative public image, right? Scorpions, spiders, snakes, sharks, and bats. None of those do more for your daily benefit than bats.

[Fernanda]: Let’s explain: Bats contribute to the ecosystem on a daily basis.

The first is pest control:

[Rodrigo]: You have had your coffee, or you’ve had your tea, or you’ve eaten some tacos, some tortillas, some tamales—any corn product. Bats are the most important pest controllers in the world. They control pests in corn, coffee, tea, beans, rice, and many other agricultural products.

[Fernanda]: Like cotton, too. Rodrigo says that without bats, we would not have many crops. The second service they provide is the dispersal of seeds, of many types: guavas, black and white zapotes, plums…

[Rodrigo]: And many other plants that we eat because we get them in the market are there because bats have been dispersing their seeds for millions of years. So having those fruits now is a service that bats provide to us.

[Fernanda]: Bats spread three to five seeds per square meter of rainforest in a single night. While birds, which are more visible to us, disperse between half a seed and one seed.

The third benefit is pollination. Many species of bats pollinate plants that have substantial economic and ecological value for the region. For example:

[Rodrigo]: Agave is pollinated by bats. So if you like tequila, if you like mescal, bacanora, raicillas, pulque, maguey worms, the rope with which a piñata used to be tied, we have all of that thanks to the fact that bats are the most important pollinators of agave.

[Fernanda]: Explaining the three services to the ecosystem is one of the arguments that Rodrigo uses to spread the message that bats are not threatening creatures, but the exact opposite: animals that make our daily lives possible. Even if we don’t see them.

[Rodrigo]: Documenting the services they provide us, calculating those services in pesos and cents and disseminating and promoting knowledge about them, ensuring they stay, maximizing them, and making them known to people, is the least I can do to defend a group of animals to which we really do owe a whole lot.

[Fernanda]: Rodrigo devotes a large part of his time to sharing his knowledge about bats in presentations, talks at universities, and publications in scientific journals. The problem that he and many of his colleagues see is that it is generally difficult for research like this to make it out of the scientific community. There are usually many obstacles for the rest of us to hear about it.

That is why, beyond the academic community, his goal is for the message to reach us all, inside and outside the universities.

In 2012, in one of those efforts to make science more accessible, Rodrigo agreed to an interview with a famous Mexican magazine called TVNotas. This is a weekly publication of gossip about Mexican television celebrities and related content. Let’s say that it is a magazine where you would never expect to find popular science, but they did publish an issue with four full pages on the benefits generated by bats.

[Rodrigo]: I even sent them to the entire Institute of Ecology, because we are always saying, “You have to publish in high-impact journals,” and this and that. High-impact magazines: Ecology prints at best 10,000… 10,000 copies. Evolution prints 15 thousand copies. Right? TV Notas prints 800,000 copies.

[Fernanda]: It’s the magazine with the highest circulation nationwide, and you see it everywhere: in the dentist’s waiting room or at the hairdresser…

[Rodrigo]: And the most beautiful thing of all was that the week after it came out, I went to the market on wheels, here near my house, and the lady who sells lemons stares at me. “You were in the magazine, and now I know that bats are not bad.” Well, I almost kissed the lady. You can just picture it.

[Fernanda]: Moments like this are great steps forward in the mission that Rodrigo set for himself as a teenager. But to have a greater impact, he needed to get certain licenses that accredited him to reach positions from which he could make decisions, obtain budgets… And almost always, the way to start is to study abroad.

So when he finished college, in 1985, he decided to get a scholarship to travel to the United States and continue his graduate studies at the University of Florida.

There, Rodrigo expanded his specialization, researching not only bats, but also many other mammals. Seven years later, he returned to Mexico to apply what he learned.

Rodrigo became an advisor to Mexico on biodiversity issues and won numerous awards for his career. One of them was the Whitley Prize for Nature Conservation, which is awarded in England by Princess Anne and which he won twice, in 2004 and 2012.

In 2012 he traveled to England for the award ceremony, and at the reception he met someone who touched him even more than the award itself. Out of the corner of his eye, he caught a glimpse of his childhood hero, the environmental documentary filmmaker Sir David Attenborough.

[Rodrigo]: I became the most pathetic Justin Bieber fan. I mean, I was (funny shout) like that, just like that.

[Fernanda]: David Attenborough has made dozens of nature documentaries for the BBC. He is one of the most important people in the media. In 2012, the UN gave him a lifetime achievement award. Rodrigo used to watch his documentaries when he was a child. But now, as an adult, he watched from a distance, waiting for the best moment to introduce himself, until he decided to get closer.

[Rodrigo]: I said, “I don’t give a darn right now, I’m going be a real chilango.” So I go ahead at once and I introduce myself. And I tell him, “David, you don’t know what you have done. You have changed the world, and you have changed my life. When I grow up, I want to be like you,” I told him.

[Fernanda]: That was the start of a conversation that ended in mutual admiration. David and Rodrigo talked for hours about bats, until Rodrigo received a proposal from his childhood hero: to make a documentary together about his work, in Mexico, with the entire BBC production team. Obviously, Rodrigo accepted.

[Rodrigo]: They followed me around for four months in Mexico, from Chiapas to Sonora, Yucatán, Mexico City, Guerrero… a lot of places, documenting my work. And then I asked, as a special favor to David, that he narrate the documentary. And wow! He accepts.

[Fernanda]: In that documentary, Rodrigo went from being Cayopollín to receiving his second nickname—this one is more official…

[David Attenborough]: Rodrigo really is The Batman.

[Daniel]: Rodrigo really is Batman. The Mexican Batman. And his work would be decisive. It would even become, literally, a matter of life and death.

We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, we were hearing how Rodrigo Medellín, a Mexican scientist, dedicated much of his career to protecting bats and showing how important they are to humans. He got many people to stop looking at them in fear. But it still wasn’t enough to keep them safe…

Fernanda Guzmán continues the story.

[Fernanda]: In the mid-1990s, when Rodrigo returned to Mexico after completing his PhD, a species of bat became very important to his work: Leptonycteris yerbabuenae, more commonly called the lesser long-nosed bat.

[Rodrigo]: And they are the bats with the sweetest personality you can imagine.

[Fernanda]: Because unlike other animals, when you hold them to study them, they do not usually fight or bite. They let you examine them in peace. They are medium in size, with an elongated face…

[Rodrigo]: Their eyes are very large compared to other bats. Their ears are small and triangular, their fur is grayish brown…

[Fernanda]: They live in a wide area of our continent that goes from southwestern Arizona and New Mexico in the United States, passes through central and western Mexico, and reaches Guatemala and El Salvador.

All eyes have been on this species for years, because it was put on the list of endangered animals in the United States in the mid-1980s. But since it is a species that is shared with Mexico, they had to determine its status in this country as well. It was added as an endangered species in 1993.

And they weren’t the only bat species whose population had been drastically reduced.

Unlike the Batman of Gotham City, the Mexican Batman does not work alone. To try to save these bats, a team was needed. This was the origin of the Program for the Conservation of the Bats of Mexico. Their first meeting was held in April 1994.

[Laura Navarro]: We have a group of bat researchers around us, many people from Latin America and other places who, in one way or another, have shared some of our adventures with bats.

[Fernanda]: She is Laura Navarro, an educator graduated from UNAM, and she has been working shoulder to shoulder with Rodrigo in the conservation program for 28 years, since its inception.

Rodrigo and the team began monitoring the activity of various types of bats in ten key caves that were shared by several different species throughout the country.

That was when they realized that different bats were disappearing drastically. And they verified that one of them was the lesser long-nosed bat. Alarms went off.

[Laura]: And above all because it is the species that pollinates the agaves from which we obtain all our Mexican spirits: tequila, mescal…

[Fernanda]: So that could also put their production at risk. Which makes it almost a national emergency.

[Laura]: Red alert. Red lights, beep, beep, beep.

[Rodrigo]: That makes bats a very important economic asset for much of Mexico’s industrial activity.

[Fernanda]: There are many reasons why the long-nosed bats began to disappear. The main cause was the destruction of their shelters. Many caves were destroyed, either to use the land for construction, or out of sheer fear of bats. Also, the lack of food throughout the areas on their migratory routes.

Laura: There are other things that also interfere and that are unpredictable and do not depend on something that we do—climate factors as well, right?

[Fernanda]: If winter starts too early or if it suddenly rains a lot, that can affect them, too.

It is also important to note that most bat species have a single pup once a year. If a maternity cave—that is, where pregnant bats give birth and nurse their young—is disturbed, an entire generation of bats would be lost and they won’t have pups again until the following year.

Once the factors had been determined, action had to be taken based on a recovery plan, to reduce the loss of this species and other types of bats. So Rodrigo and the team put together a three-way strategy.

[Rodrigo]: The three pathways are 1: Environmental education. 2: Basic research. And 3: Direct conservation actions. And these three pathways feed off each other in all directions.

[Fernanda]: For the research phase, the team spent more than two decades closely observing the long-nosed bats. It was not a simple process, nor instantaneous. They had to spend years identifying which were their most important colonies and where they lived, what they used as food and also their migratory routes, to know how safe the bats were, if they had enough food during their long trips or if they suddenly changed their direction for some reason.

Once they became experts on the theory, it was time to put direct actions into practice.

Once their food sources were identified, they were able to help them get it more easily. Over time, they perfected the monitoring of the migration routes and tried to keep them secure and with enough food. They also worked for years to strengthen the security of their shelters and maternity caves, turning some into protected natural areas.

But the first point that Rodrigo mentions is important: environmental education. Without this part of the process, no research effort and no conservation action could work. So everything they had learned about bats over the years had to be passed on to the people who lived near these shelter caves. That was the culmination of the entire plan.

[Rodrigo]: Talking with the owners of the land where the most important colonies are located, the most important caves, to explain to people why it is necessary for them to join the fight to conserve these bats. And every time we go to a new cave and tell people how important those bats are, those people immediately become bat advocates.

[Fernanda]: They created workshops and outreach material specially designed for each community. The people were even taught to see bats as allies. For example, they promoted the production of foods made from fruits that the bats pollinate, with a view to eventually marketing these products. So the bats help them, and they help protect the bats.

They also organized ecotourism visits to see bats, or even took one directly to people so they could see it up close, either a live one or a skin. And that managed to bring down the fear that some people may have.

[Laura]: A very important part of bats that people sometimes don’t realize or don’t know about, because they haven’t had the opportunity to see them up close, is that bats are mammals, like a dog or a cat. They have soft hair, and when you touch them, the feeling that they are slippery, slimy or gross changes completely. It’s very nice to see that, you know? When people discover for the first time that… that they are not what they imagined them to be.

[Fernanda]: Of course, this is not an invitation to go touch bats. The encounters that Laura mentions are controlled. But it is good to realize that, like any mammal, they have things in common with us and with the animals that are usually around us in our daily lives.

In this way, the mission is not only in the hands of scientists, biologists and conservators, but of the entire population that lives near the bats, working on the same team to protect one more member of the community.

And it worked. Finally, after a long journey of more than 20 years of joint efforts, the protection program team realized that the long-nosed bats were increasing their population. Their colonies grew large enough to even consider removing them from the endangered animals list. This is Rodrigo at a press conference in 2013:

[Rodrigo]: So I am very happy to announce here that the lesser long-nosed bat has finally left the endangered species list to become a recovered species. It’s time to celebrate.

When I announced it, I swear I felt a tingling all over my body. My hairs stood up. I felt that… “This just can’t be. It’s wonderful that we managed to do it.” And it’s a completely shared thing, eh.

[Fernanda]: To date, this is the only mammal that the Mexican government has been able to remove from the list of endangered species.

[Laura]: It is undoubtedly an important moment when you can say, “Wow! Everything we’ve done has been worth it.” But hey, for me it’s always a reminder of what remains to be done as well.

[Fernanda]: And to make sure these advances are maintained. There are about 140 different species of bats in Mexico, and unfortunately, many other species of this animal are still seriously threatened.

The main threat is still human beings and the fear of bats… And in 2020, well… You know…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Televisa News Archive]

[Denise Maerker]: The contagion of more than 200 people by a new virus in Asia has set off alarms at the World Health Organization.

[Fernanda]: The novel coronavirus became a new excuse to be even more afraid of bats.

The first time Rodrigo heard that bats were related to the coronavirus was from one of his colleagues, the scientist Shi Zheng Li, from China.

[Rodrigo]: She published an article saying that this virus, SARS-COV-2, was a virus of probable bat origin. That’s how she published it, and from there the media repeated it as, “Bats are giving us…”

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist 1]: All eyes are on the bats.

[Journalist 1]: Now let’s talk about the origin of this virus. It could have originated in bats.

[Rodrigo]: We have fallen into the misfortune of blaming these poor animals, although they have nothing to do with it.

[Fernanda]: To a certain extent it is understandable. We were locked up at home, afraid. We knew there was a threat outside, but until then it was invisible. For a moment, the bat became the image of the enemy that we needed to make tangible…

And we needed to defend ourselves…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: In Cajamarca, Peru, hundreds of bats were burned for fear of virus transmission.

[Journalist 2]: The Peruvian authorities urged the population to stop killing bats, after rescuing 200 of these mammals that were going to be burned by farmers, alleging that they transmit the novel coronavirus pandemic.

[Rodrigo]: When this topic began, many people, in many places around the world, began to kill bats and began to drive away bats and get rid of bats.

[Fernanda]: Cruel cases like these also occurred in Cuba, India, Indonesia and Rwanda. In Mexico, some 25 bats were found dead under a bridge in the city of Mérida, in the southeast of the country. And although we do not know for sure what killed them, it is suspected that it was an attack organized by people who live in the area. So now, Rodrigo’s scientific outreach needed to be reactivated as never before.

[Rodrigo]: Never in my life have I worked harder than in the last year and a half. I have been focused on giving conferences and talks and interviews and meetings and much more to improve the public image and prevent people from continuing to blame bats for this.

[Fernanda]: At the beginning of the pandemic, bats were placed at the center of the conversation about the crisis. It is seductive, perhaps, to find the culprit, especially when you can blame an animal that so many of us already have some misgivings about.

As if it were the bat’s fault. As if we human beings had nothing to do with the spread of diseases like Covid-19.

[Rodrigo]: I have said it many times: The first line of defense against the next pandemic is the conservation of biodiversity.

[Laura]: The conservation of species is directly related to the survival of human beings, right?

[Fernanda]: For Rodrigo and Laura, thinking about the health of the ecosystem and other species is also thinking about our own health. And although imagining a drastic change in our lifestyle can seem like an unattainable scenario to many of us, Rodrigo thinks that it can be achieved.

[Rodrigo]: I am absolutely convinced that it is possible. But we have to do everything on our part, both scientists and communicators, as well as the general population. We have a lot to do. And people are very willing to understand it, to learn it, to incorporate it into their… their habits.

[Fernanda]: And we can start by looking at bats through the eyes of the Mexican Batman: Imagine them as our childhood friends, the ones who lived in our own house, the ones we watched, the ones we fed. To take care of them, and at the same time, take care of ourselves.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Fernanda Guzman is a journalist and lives in Mexico City.

The episode was edited by Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas, Nicolás Alonso and me. The fact checking was done by Désirée Yepez and Bruno Scelza.

The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with original music by Ana Tuirán.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Arguelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, José Díaz, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Rémy Lozano, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo y Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Natalia Sánchez Loayza is our editorial intern.

Selene Mazón is our production intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.