Lost in San José – Translation

Share:

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Addresses in Costa Rica are an enigma.

[Sergio]: From the Pollo Macho, the corner that’ll be facing la Iglesia de la Agonía, up like 300 feet toward the Stadium.

[Andrea]: One hundred meters west and 200 north of the Jarra Garibaldi restaurant.

[Camilo]: From the church in Sabanilla, one kilometer east, 100 south, 25 east. It’s the fourth house on the left, brown fence, yellow house, ok?

[Ana]: From the Porvenir Catholic church, 50 meters north, 250 meters east, the two-story house on the right.

[Gustavo]: From the mango tree, go straight until you hit the fence, turn right and it’s next to the Chinese grocery store.

[Daniela]: You take the highway toward Guancaste, there it’s, do you know the restaurant, Caballo Blanco. Ok, below there’s another smaller restaurant. There turn right and keep going for about three kilometers, and then you’re at my house. And I’m like: “Mmm, OK. Super easy.”

[Daniel]: Super easy. Ticos themselves admit it: the way they give directions is…

[Woman 1]: Terrible.

[Man 1]: Very bad.

[Man 2]: Super complicated.

[Man 3]: Sonofa— (laughs).

[Man 4]: We don’t do it formally.

[Woman 2]: It’s difficult. It’s hard people who know the cardinal directions and all that.

[Woman 3]: You give directions based on a point of reference.

[Man 5]: The system for giving directions is Tico-style, that’s it, Tico-style. It’s not normal.

[Daniel]: They don’t use a system with signs for streets and avenues in most of the city. What they use are points of reference like parks, restaurants, churches, bars —lots of bars. Sometimes, they’re even places that don’t exist anymore.

But its more than that. When your lucky, the directions include north, south, east, and west, but most of the time, it’s just up, down, uphill, downhill, forward or backward, right or left. All relative to the person who’s speaking and the person listening.

Here at Radio Ambulante we’re fascinated what Ticos do to get around. It seems like an impossible task, and still, they almost always manage. Maybe after a few calls to the person who gave them the directions.

The question is: why? Why did Ticos never adopt a formal system for directions? Our editor Luis Fernando Vargas was born and raised in the middle of this labyrinth. So, we asked him to explain it to us. Here’s Luis Fernando.

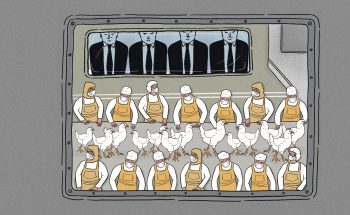

[Luis Fernando Vargas]: Let’s talk about a very difficult job in Costa Rica: being a mail carrier.

You not only have to deal with the terrible traffic in the city and the possibility of being robbed but also directions like the ones you heard before. I need to clarify that there are streets and avenues with names and numbers. In theory, but in practice, not at all. No one uses them.

[Jonathan Araya]: They say from the green balcony, one and a half kilometers west and they just put “pink house.”

[Roosevelt Rojas]: From Ricardo Saprissa 1000 east and 50 east. Yellow house.

[Jonathan]: From the Tennis Club on Sabana, three long blocks, in the direction the sun sets.

[Roosevelt]: Barrio Virginia, one kilometer along route 32. And it wasn’t one kilometer. It was ten.

[Luis Fernando]: That’s Jonathan Araya and Roosevelt Rojas. Two mail carriers with the company Correos de Costa Rica. Every day they deal with the mental knots that Ticos make. It’s obvious: someone without experience would be able to deliver one message a day. That’s it. Every letter, every package that has to be sent is like deciphering a treasure map. Only the prize at the end is the next delivery, followed by another headache.

Even though it sounds silly, the way we give directions is a serious problem for this institution. The operations manager himself, Geovanny Campos, says so:

[Geovanny Campos]: Without a doubt, at least from my perspective, uh… the biggest operational constraint we have is that we can’t count on an adequate system for giving directions which is reflected in every one of our deliveries, every package, every parcel we send.

[Luis Fernando]: There’s a high return rate for packages and letters because, sometimes, the directions are just impossible to decipher.

[Geovanny Campos]: Around 18 to 20 percent of outgoing items can’t be delivered.

[Luis Fernando]: But Geovanny says that that figure would be nearly double if the mail carriers returned every deliver that didn’t have a complete or correct address.

[Geovanny Campos]: This is due to the fact that the mail carrier, through their own knowledge which they develop over the course of months, primarily over the course of years, is only able to deliver packages using the person as a reference, using the person’s name.

[Luis Fernando]: Well, the name of the person, the neighborhood, the municipality, at least. And it’s not like they’re psychic, either. Costa Rica is a country of 5 million people, imagine how many Luis Vargases there must be. But Geovanny says that mail carriers work in fixed areas. Sometimes they keep these routes for years. So it’s not uncommon for them to come to know the people who live in the different neighborhoods where they work by name. Because going around asking people for Juan Pérez or Benito Ventura becomes an involuntary part of their job. It’s a survival mechanism.

Other times, letters arrive by the sheer insistence of the carrier. Take for example this case from Jonathan Araya, who we heard a few moments ago. The address he had to find was this:

[Jonathan]: From Contraloría, 600 meters south and 400 meters west.

[Luis Fernando]: And here that even sounds normal, right. I mean, the building Contraloría General de la República is a well-known location, the directions they gave have cardinal directions and the distance you need to travel. It’s not ideal, but it’s manageable, good by Tico standards. Until they give one more detail:

[Jonathan]: And it said: “The house in front of the bag of trash.”

[Luis Fernando]: Great point of reference. This would work if there were just one bag of trash in the area.” But on a day like Monday, when everyone takes out their trash, well it’s rather difficult to find the house. Jonathan spent two or three days trying to find the place.

[Jonathan]: So I had to ask and ask, at the social hall and everything. One day I ran into a guy on the street, and I ask him: “Do you know this one? The thing is…” “Oh, yeah,” he says, “There, where that bag of trash is.” I say: “How strange. Where would the bag of trash be?” And it was a bag that was posted on the gate, like drawn on, and it said: “Trash” (laughs).

[Luis Fernando]: A drawing to indicate to the neighbors that they had to put their trash there so it could be collected. Obviously.

Generally, Jonathan takes these things in stride; he even laughs. Although…

[Jonathan]: You kinda get annoyed and say: “Hey, how can I do anything with these directions, right?”

[Luis Fernando]: And he’s right. Listen to this example from Roosevelt Rojas.

[Roosevelt]: There’s an address that I still get, I get it and deliver it because I know it, right? And they get international deliveries from all over, right? Letters, everything. Uh, they put “the house with the rocking chairs” on it.

[Luis Fernando]: And it’s not a business that’s called that. They’re asking him to look for a house where there are some rocking chairs.

[Roosevelt]: They put: “From the Tibás Cemetery, headed downhill. House with the rocking chairs. Brick wall. Red fence.” And it doesn’t have bricks anymore and the fence is black. The only things that are still there are the three rocking chairs.

[Luis Fernando]: Three old rocking chairs that don’t work anymore.

[Roosevelt]: Gosh, the first time I went looking for that address, gosh, I walked through nearly all of Las Rosas in Tibás. And that, I mean, it’s huge. And looking for it, uh, because those are international deliveries. I mean they have to make it.

[Luis Fernando]: There are too many absurd examples. Geovanny Campos, who was also a mail carrier years ago, remembers a few.

[Geovanny]: In front of the beach, two and a half kilometers on the route. House with a garden wall with tires painted blue.

[Luis Fernando]: As if Costa Rica didn’t have hundreds of kilometers of beach. But, besides that, on what route? Starting where exactly? Or there’s this one too.

[Geovanny]: Company X, from the newspaper La República, 12 kilometers north.

[Luis Fernando]: Ok, let’s say you can count 12 kilometers, it’s hard, but you can do it. But on what street. There are several headed north, right? The country doesn’t just have one highway. It’s small, but not that small.

My address is: La Uruca, San José, from Campanita kindergarten, 50 meters north and 500 meters west. Or if I want to make like harder for myself, I can say from the old Canada Dry —a factory that closed before I was born— 300 meters north, 100 east, 50 north, and 500 east. And I could even give other directions if I wanted.

Gaby Brenes, one of my coworkers here at Radio Ambulante who’s also a Tica has an address that’s just as odd.

[Gaby Brenes]: San Antonio de Desamparados, 100 meters south of El Pollo Granjero or 100 meters south of the San Antonio de Desamparados mannequin.

[Luis Fernando]: The mannequin that Gaby’s referring to is… Let’s see, we’ll put a picture on the website, so you can see it, but I’ll tell you. It doesn’t quite qualify as a statue. It looks like those Ronald McDonald figures more or less, but it’s not a clown, but rather what’s supposed to be a farrier in an apron. In the neighborhood, they say that he used to have two tools in his hands —a hammer and pliers— but they aren’t there anymore because someone stole them. You have to look at the picture to understand how absurd it is.

But let’s continue.

Gaby remembers when she was young and her parents threw her a birthday party, the invitation they gave out to every kid came with a map.

[Gaby]: My dad sketched it out by hand. So, he would draw it street by street, even the streetlights, the intersection, and what you do is at home you scan it, you copy it and you put this little sketch, cut out by hand, on every invitation with glue.

[Luis Fernando]: Because if you didn’t send the sketch, of course, none of the guests would show up. I should clarify that Gaby doesn’t live in a rural area where a little map like this would be more common, but in the middle of the capital, in a residential neighborhood.

For a lot of you, this will sound complicated, but for us it’s natural. We don’t live in specific places, but rather in places that depend on reference to other places, which are necessary so the person can understand and get to our house. It’s having thousands of addresses, as if it was a movable city, made of sand, an ever-changing map. It’s not static.

I mentioned that there are streets with names and numbers. They’re assigned when they’re built, or they’re recorded in documents from the Ministry of Public Works and Transit. You can see them on Google Maps or any other GPS system.

But it doesn’t go beyond that. In our day to day, Ticos live without this information. What’s more, we don’t even know it exists. We’re used to living without signs to guide us, getting lost, getting everywhere late because we don’t know where we’re going exactly.

The city has gone decades without street signs and house numbers. They were there once, but they disappeared. What’s more, sometimes you find a plaque on an old house with a number that’s survived over the years. They’re relics, keepsakes from another time that no one pays attention to.

The reason these signs disappeared is hard to know for sure. I went to the City Hall of San José to ask and they told me they didn’t know. I also asked the National Land Registry to see if they had any idea, but they didn’t either. None.

But Geovanny, of Correos de Costa Rica, has this theory.

[Geovanny]: As urban development progressed, which was disorganized in that it didn’t have a grid with quadrants, that kind of signage was automatically lost.

[Luis Fernando]: In other words, as the city was growing irregularly, without a grid or blocks as a base, signage was lost because it stopped making sense. And since it didn’t make sense and no one was using them, the few signs there were disappeared with time, when the streets and buildings changed. They disappeared, perhaps, even due to vandalism.

And San José, which is the center of the country, has suffered important changed since the ‘50s.

[Andrés Fernández]: A situation begins in which the iconic buildings from the Liberal Republic are replaced by a series of iconic buildings from the Second Republic.

[Luis Fernando]: This is architect Andrés Fernández, who is also a historian from San José. The Second Republic is the name for the period after the civil war in 1948, during which a new constitution was created. With the Second Republic, you see…

[Andrés]: The destruction of the Presidential Palace to build the new headquarters for the National Bank. Followed by the destruction of the National Palace to build the Central Bank. Followed by the destruction of the Santo Tomás University to build the Anglo Bank.

[Luis Fernando]: And perhaps the most emblematic change…

[Andrés]: The destruction of the National Library in 1970 to be turned into a parking lot.

[Luis Fernando]: It as if government leaders weren’t interested in San José as a city, but rather a trading center. A center where people do business. And what had the greatest effect on this transformation in the city was the creation of peripheral neighborhoods.

[Andrés]: Which took people from San José and emptied our traditionally working-class and middle-class neighborhoods.

[Luis Fernando]: And along with that movement of people…

[Andrés]: Street signs were left to disappear, and consequently, house and dwelling signs are left to disappear to the point that today they’re almost folksy, if not snobbish.

[Luis Fernando]: I only learned about seven years ago that the street I live on has a number. It’s 43rd avenue. I know it because at that time the city government put signs all over San José’s city center. They spent more than a million dollars doing it. The mayor said that it was to eliminate the “archaic” system of giving directions. It was an attempt to have a formal system and be like other 21st century countries. Like first world countries, though houses and businesses still didn’t have address numbers. We can’t be that first world.

[Daniel]: After the break, we’ll figure out why they give directions in such a complicated way in Costa Rica. And also, we’ll understand what this system —if you can call it a system— tells us about the national character of the Costa Rican people.

We’ll be right back.

[Ad]: Support for NPR and the following message come from EveryAction. EveryAction is the modern and easy-to-use unified nonprofit CRM. It’s built by and for nonprofit pros, powering both online and offline fundraising, as well as advocacy efforts, volunteer programs, and grants management. EveryAction is trusted by more than 15,000 organizations, including The National Audubon Society. Learn more today by visiting EveryAction dot com slash NPR.

[Throughline]: The world is a complicated place, but knowing the past can help us understand it better. Throughline is NPR’s new history podcast, each week we delve into the forgotten moments and stories that have shaped our world. Throughline, history as you’ve never heard.

[Code Switch]: Whether it’s the athlete protests, the Muslim travel ban, gun violence, school reform, or just the music that’s giving you life right now. Race is the subtext to so much of the American story. And on NPR’s Code Switch, we make that subject, text. Listen on Wednesdays and subscribe.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, Luis Fernando was telling us how for decades, in Costa Rica there were no street signs. And there still aren’t in most of the country.

But the lack of signage isn’t necessarily the reason why Ticos give such complicated directions.

Luis Fernando continues the story.

[Luis Fernando]: Architect Andrés Fernández has a theory:

[Andrés]: Our space and our time are governed by a sense of indeterminacy in time and space.

[Luis Fernando]: I know it sounds like French postmodernist philosophy. But, please, don’t get too scared. We’re going to try to make it make sense.

According to Andrés, in Costa Rica, we live in a temporal limbo where the past and the present mix to form our geographic space. The bars of yesteryear combined with the businesses of today. It’s as if time stood still.

The best example in the country is the old fig tree, a tree that isn’t there anymore, but that is still the most famous reference point for directions east of the capital.

[Andrés]: In other words, not only do I need to know where the fig tree was, but I also need to know that it was a fig tree. In other words, I have to send myself back into the temporal past, which is also a spacial past because the fig tree isn’t there anymore, and direct myself from there.

[Luis Fernando]: Things that aren’t there anymore still exist in memory and as such we make them exist in reality. And according to Andrés, that logic comes from our rural, agrarian origins. Remember that Costa Rica was and still is a country of farmers. For us, time has a different logic. And we’re referring to time in its modern conception: time governed by minutes, seconds, hours. In the country, time isn’t measured the same way.

[Andrés]: Why? Because our time is cyclical. We depend on the rain for the harvest to come. We depend on it to stop raining for another thing to happen and for the moon to be this way and the sun to be this way. The working day for a Costa Rican since the 16th, 17th century is from sunup to sundown, etc..

[Luis Fernando]: It’s a concept of time that repeats, that doesn’t move forward.

[Andrés]: And with space, the exact same thing happens.

[Luis Fernando]: It’s a static concept of space, where things don’t move, despite the passage of time. And that way of life has persisted through the years —through the centuries, rather— despite the fact that modernity has descended upon us with its productive logic.

According to this theory, Ticos continue seeing time, and especially space as rural farmers. They don’t think about coordinates, which are an abstraction, like in the modern world. But rather we think about things we can see, appreciate, touch, and even remember. Things that are useful, or that were at some point in our daily lives. The quadrants on a map don’t mean anything, but don Pedro’s grocery store does because that’s where we go when we need something to eat. A street number doesn’t mean anything either, but the hall where I would go dancing on Saturday, that place does persist in memory. Even though it doesn’t exist anymore.

It’s nice if you really think about it. Instead of quadrants ruled by numbers, our space is organized by places that are meaningful to us. Generally gathering places where people socialize or socialized. Points that generate memories, points that give life to the places in which we live.

The question is, then, how can a country coexist in the modern era with a sense of time and space that’s centuries old. The answer is: with a lot of issues.

In 2011, an interesting study was commissioned. In the study, they measured the extra time a person needed to spend in order to get to a place due to the lack of a formal directional system. Then, that time was multiplied by the cost of living, to quantify how much money was wasted in the country because of this. According to Correos de Costa Rica, the figure was 720 million dollars a year. I repeat: 720 million dollars! A lot of money for such a folkloric problem. This is Geovanny Campos, from Correos de Costa Rica.

[Geovanny]: Continuing with this system for much longer, without a doubt will diminish our capacity, diminish our commercial competitiveness and dynamism of the business sector in Costa Rica.

[Luis Fernando]: To him, we have to modernize the directional system, do it like they do in other countries.

[Geovanny]: For me, the goal should be productivity for all of Costa Rica. How do we become more agile logistically speaking, in terms of moving things and people? With the system we have, we’re going to have the same problems, the same lags, the same amount of wasted time as you and I have today, right?

[Luis Fernando]: Architect Andrés Fernández feels the same way: We have to change the system, especially because of the time we waste looking for addresses.

[Andrés]: That is problematic from the perspective of modernity. Very problematic because it’s a lack of respect. In other words, the hourly division of 24 hours and hours in minutes and minutes in seconds is a matter of convention. In other words, we want to be clear that that isn’t that way because that’s the way it is, but rather it helps everyone live better.

[Luis Fernando]: Because other people’s time is as valuable as mine.

Another thing we have to consider is the tourists. This is a tour guide I met in San José. He was with a group of five people.

[Sentences in italics were spoken in English in the source audio]

[Tour guide]: The address of the National Theater. Where is the National Theater? The address. The National Theatre is next to the Plaza de la Cultura. The theater is next to la Plaza de la Cultura. Where is the Cultural Plaza? Where is the Plaza de la Cultura? Next to the Grand Hotel. Next to the Grand Hotel. Where is the Grand Hotel? Where is the Grand Hotel? In front of el Ministerio de Hacienda. In front of el Ministerio de Hacienda. Where is the Ministerio de Hacienda? In front of the National Theater. In front of the National Theater. Easy to find. Easy to find (laughs).

[Luis Fernando]: It seems like a joke, but it isn’t. This captures the essence of our way of giving directions.

Tourism is vital in Costa Rica. Last year, 2018, the tourism industry brought nearly 4 billion dollars to the national economy. More than 6% of GDP. It’s the source of employment for more than 200,000 people. But for many, being a tourist here, in Costa Rica, with our directions, is a headache when it’s not an adventure. Some people like it, it seems folksy to them, but in the end, it’s not very practical, and it can even be expensive: not just because we waste time, we lose tourists and we lose money.

I went to the street to see what some of these tourists thought.

[Woman]: Funny I guess. It’s hard to get used to. It’s hard to find things.

[Luis Fernando]: He says, “It’s funny, but hard to get used to, hard to find things.”

[Man]: It’s kind of confusing. Yeah it is.

[Man]: Yes, it can be a little confusing.

[Woman]: Everyone says: 20 meters, 200 meters, turn right. Like they’re Waze or Google Maps or something like that.

[Luis Fernando]: And my favorite answer.

[Man]: It’s bizarre. It’s bizarre.

[Luis Fernando]: It’s bizarre. Yes, it is. Most of them admitted that they prefer not to ask for directions. Instead…

[Man 1]: We’re just using Google Maps.

[Man 2]: Uh, we’re using Google Maps to get around.

[Man 3]: We use Google Maps, and it guides you.

[Luis Fernando]: Google Maps. Waze. Uber. We’re in an age of hyper-localization, and here in Costa Rica, we’re not even going through the age of the map. It’s an alternative to the informal direction system. You put in the name of the place you’re going to, and, if it’s not there, you put in the name of the nearest reference point.

It’s substituting the lack of coordinates with perfect coordinates, which make it so it’s not even necessary to get to know the city, but rather it guides you turn by turn, street by street, to where you want to go. The city also becomes a city of sand: there are no streets or avenues or plazas, there are just specific places, right and left.

It’s efficient, yes, more specific than the Costa Rican system, but I also wonder what it leaves to the wayside. I know it’s contradictory, but despite how absurd our way of giving directions is, it has its charm, because it makes you get to know the city, its shapes, its colors. We have to know where we live, be very keen observers, make the space our own.

There’s a certain poetry to the house with the rocking chairs, poetry that house number 72 would never have. I’m not saying numbers are bad, of course. I understand that we’ll have to progress toward that. But I admit that part of me will miss the house with the rocking chairs and its neighbors.

But how do you change something that’s so ingrained in Costa Rican culture? Something that we haven’t been able to change for centuries. The answer is logical, simple: children.

[Geovanny]: We know, for example, that in school, in some grades —generally in fourth grade— you see the subject of how to write a letter, where to put the return address, where is the destination and how to do it using cardinal directions. And then I learn the directions. But we’re teaching them the old way.

[Luis Fernando]: I wanted to test that theory.

[Diana]: I’m Diana, and I’m 11 years old.

[Luis Fernando]: She’s my niece.

Say, do you know your house’s address?

[Diana]: I think so.

[Luis Fernando]: What is it?

[Diana]: Uh, there. Behind the school (laughs).

[Luis Fernando]: Not very promising.

Did you learn directions and all of that in school already?

[Diana]: Something like that.

[Luis Fernando]: But she doesn’t remember much.

[Diana]: No.

[Luis Fernando]: And do you remember which way is east, north, south?

[Diana]: Just a little. Something like that, I don’t know. I don’t, I must have forgotten.

[Luis Fernando]: I asked how she would do it if she had to give the address of her house.

[Diana]: Uh, on a paper, like how to get there, I don’t know.

[Luis Fernando]: With a sketch, a drawn map. Just like Gabby, my friend, at her birthday party.

Diana is a good student, smart, and she lives in an area with signage, but it appears that she still doesn’t understand how to give directions beyond “My house is behind the school” and with luck you know the name of the school. It’s as if giving directions weren’t a fundamental part of the curriculum. I don’t remember exactly when they taught me to give directions in school, but I’m sure they didn’t do it with street numbers and house numbers.

As we already said, not everywhere in Costa Rica has signage, and the places that do are concentrated in the center of the country, and on top of that, children aren’t learning how to navigate their city; it seems like the Costa Rican way of giving directions isn’t changing any time soon. Unless something is done in the schools.

Before reporting this story, I hadn’t put a lot of thought into our directions. I mean, I mentioned it to my colleagues at Radio Ambulante, people from other places, who were always stunned by our idiosyncrasy.

And well, when I got to researching the topic, I realized the scale of the problem. This goes beyond being Macondo-esque and tropical. It’s more than saving time, discomfort, frustration, or money. It also saves lives.

Because another institution that suffers as a result of Costa Rican directions is the Distinguished Fire Fighter Corps of Costa Rica. I spoke with their director of operations, Luis Fernando Salas.

When they respond to emergencies…

[Luis Salas]: A lot of the time, the person, uh, well, mixes up their cardinal directions. So they tell us it’s north and maybe it’s east or west. So, look, if the unit makes it to the address that supposedly was given to us originally, then we call the people back and we tell them: the unit is at the place and we can’t find you.

[Luis Fernando]: So, in the middle of an emergency, in the heat of the moment, they stop and meet on a point that the firefighters and the person know.

[Luis Salas]: We have to run into businesses, for example, and say: “Look, we’re at this or that grocery store.” And then if the person says: “Oh, yeah, that’s 200 meters from my house You have to go down that…” So then we look for that… that route to the person. But in some cases, I repeat, it’s difficult.

[Luis Fernando]: The firefighter corps responds to more than 65 thousand emergencies per year. Sometimes responding to 450 or 500 calls a day. Each with their particular address.

[Luis Salas]: When it’s a fire that’s already in progress, it’s… it’s easier to get there, because we get a lot of calls.

[Luis Fernando]: Besides…

[Luis Salas]: When there’s a fire, the trucks go out and they say: “Look, let’s see: Desamaparado, toward Aserrí, at the intersection.” That’s what they say (laughter). OK, but if you go out and from the station, you see a column of smoke, you say: “Yes, that’s right. It’s toward… toward south of Desamparado”, and you find it alright.

[Luis Fernando]: The problem is when they call saying:

[Luis Salas]: “Look there’s a short circuit in the meter at a house in this or that sector.” Then it’s something that… sometimes even when you’re in the area, it’s not even visible. If the address is a little difficult, it’s much harder.

[Luis Fernando]: It’s the emergencies that aren’t easy to see that cause the biggest headaches. In order to resolve this problem, the firefighters go out every week to check the water intakes, that is, the location of the fire hydrants. And during these checks, at the same time, they study the important points of reference in the area they’re responsible for.

[Luis Salas]: So now all of the firefighters in Nicoya know where city hall is, where the hospital is, where the guard station is, the police station, the Red Cross, which are points that are frequently used by the people in the neighborhood.

[Luis Fernando]: Without this protocol, who knows how many tragedies we would see in the news.

And that’s something I have stuck in my head. The tragedies that occur because of the lack of a formal direction system. A few months ago, I read about a five-year-old boy who died because he was abused by his parents.

A psychologist reported it to 911 five days before his death, but apparently, he didn’t give exact directions, because, despite the fact that officials from the Patronato Nacional de la Infancia (a state agency similar to Child Protective Services) looked for the house and asked the neighbors, they didn’t find it. Now the Attorney General is investigating the parents for homicide and el Patronato for criminal negligence.

The death of a five-year-old at the hands of his parents. All for a country that refuses to change with the times.

[Daniel]: Luis Fernando is an editor with Radio Ambulante. He lives in San José, Costa Rica.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura and me. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Victoria Estrada, Rémy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, Luis Trelles, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Joseph Zárate. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.

In the next episode of Radio Ambulante: a community in Tennessee comes together to protect a neighbor…

[Verónica Salcedo] They start to say: “We have to make a human chain!”

[Cathy Carillo]: We locked hands around the van on both sides. It was neighbors, organizers, all the people that were there.

[Daniel]: The story of this amazing act of resistance, next week.