Translation – Juror #10

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

Yes. Well, uh, I still hear, well, what they call “tiroteos”, gunshots. At all hours of the day. It doesn’t have a schedule. That’s honestly when it happens. But yes, when I was younger it was even a little worse…

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: We’ll call her Mariana. That’s not her real name. She asked us not to use it. She lives in a neighborhood in Puerto Rico called Sabana Seca, in an area called “Los Bravos”, that’s about half an hour from the capital, San Juan. It’s a rough neighborhood, controlled by two drug points… where drugs are sold… marijuana, cocaine, heroin and crack. It’s a violent place, but it’s also very lucrative. So… different gangs fight for control of the drug points. There are clashes between different groups, between criminals and the police. There are car chases and shootouts between rival gangs… sometimes in broad daylight.

[Mariana]: From what I’ve seen, a lot of kids are leaving school. These young people leave school at an early age. And, well, they don’t have a lot of opportunities to… I think, that’s why they turn to the alternative of… of the street corners, that’s what they call the drug points here.

[Daniel]: It’s a situation you see again and again in a lot of neighborhoods around the island. In the case of Los Bravos, the drug trade has been the primary source of employment for young people in the community for more than three decades.

And all of this —the drug trade, the gunfire, the car chases— intensified in 2009. And even though Mariana wasn’t immersed in that world, it was obvious that something was going on.

[Mariana]: You could see there was a lot of activity, more police… more unfamiliar people coming around.

[Daniel]: Right around then, in October of 2009, fliers started showing up for a new bar that was opening in the community: La Tómbola. At the time, Mariana was a teenager, and she did what most 17 or 18-year-olds do… she went out to bars and clubs with her friends on the weekend. But when people started talking about La Tómbola, Mariana…

[Mariana]: No, no, I wasn’t planning on going there, no.

[Daniel]: It was an open secret… La Tómbola belonged to the owner of the neighborhood’s drug points, and another group had their eyes on it. They wanted to take control of it… by force.

[Mariana]: Because of this situation —the drug war, the drug points— well it wasn’t a safe bar…

[Daniel]: Even though Mariana didn’t go to the bar’s opening night, a lot of people in the neighborhood did.

One Saturday night: in Los Bravos…

And well, you need to understand something about the area. Sometimes we associate problems with drugs and violence with urban areas, crowded neighborhoods, but Los Bravos isn’t like that. Not exactly. It’s somewhere between urban and rural. And the local culture has aspects of both. So, on opening night, they put together a parade with more than 20 horses at the bar. There was a live merengue band playing. There was food, drinks, dancing… It was a huge party.

It was almost midnight, and from her house Mariana could hear sounds like these…

(Sound of gunfire in the distance)

…and she thought for a moment that it was fireworks. But moments later she heard sirens…

[Mariana]: No, you couldn’t know the magnitude of what had happened. You couldn’t say how many were dead or wounded, or if nothing happened at all, or if it was a false alarm…

[Daniel]: According to the accounts of people who were there, at least three men with covered faces and large firearms approached the area and stared shooting. The owner of La Tómbola, along with others who were in the bar, shot back to defend themselves. There were 100 people between them. When the gunmen finally left, there were 20 wounded and 8 killed… Among those wounded was a pregnant woman. She survived, but the fetus didn’t. One more person died days later from gun wounds.

According to reports from the police, more than 300 shots were fired that night at La Tómbola.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Reporter 1]: Authorities are still at the scene and at the moment they have yet to identify the perpetrators of the shooting.

[Reporter 2]: Death took hold over the business that was literally re-opened at gunpoint this Saturday.

[Reporter 3]: Due to this historic massacre, a re-examination of the conversation concerning the crime wave that seems to be consuming the island is inevitable.

[Daniel]: The next day, Mariana learned that several of her close friends had been killed that night.

[Mariana]: I had a lot of nightmares where, uh, I heard, uh, shots, where they killed me or I got in a car crash… For a long time… [laughs nervously]… I slept with my mom…

[Daniel]: Since Puerto Rico is a US territory, and because the crime fell under federal jurisdiction, federal authorities were in charge of part of the investigation.

About two months after the massacre, they arrested a suspect: Alexis Candelario. People in the neighborhood knew him well, because he had been one of the most infamous drug-traffickers in the area. Federal authorities accused him of planning and carrying out the massacre in order to take hold of the drug point via the most violent means possible.

The case divided the local community deeply, along with the rest of Puerto Rico, because in 2013 a trial started that put Candelario’s life in the balance.

Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón… this crime, the Tómbola Massacre, would turn into a historic trial for the island. And that is the story we’re telling today. Later we’ll hear from Mariana again, but for now, we’ll hear from the people who were in charge of making an extremely difficult decision.

Luis Trelles brings us this story from Puerto Rico.

[Luis Trelles, producer]: The voice you’re about to hear belongs to Juror 10. For reasons that will become clear much later, we’re going to refer to her by the number assigned to her by the court… And the first thing we should know about her is that she comes from a world that is totally different from that of Los Bravos. She’s a successful business woman, she lives in a planned community with private security… a place with perfect patios and new-looking tennis courts. In other words, it’s a reality that is very distant from the wars over drug points.

Juror 10 also has a firm belief in the justice system. Most of all, the idea that anyone accused of a crime has a right to be judged by their fellow citizens.

[Juror 10]: Personally, I always thought that, that if they call you, you shouldn’t be a spectator or only criticize the system, instead you should contribute your small part, and I could, so why not.

[Luis]: So, she didn’t mind when she got a letter from the US Federal Court in Puerto Rico. It was 2012… and they were calling on her to be a juror. But first she had to answer some questions…

[Juror 10]: Do you know English, uh, what do you do for a living, basic questions.

[Luis]: She answered that she did speak English… and that’s key because even though Puerto Rico is a Spanish-speaking island, all the trials in Federal Court are in English.

In the end, she was selected… They told her she would serve as a juror for a federal trial for a period of 30 days. We’ve already said this, but the federal part of all this is very important because Puerto Rico has a local justice system, with its own courts and its own constitution… and this distinction, between Puerto Rican courts and federal courts, is going to be very important in this story.

So, Juror 10 was going to be part of a trial… and in the process she learned to weigh evidence and come to a verdict that is beyond a reasonable doubt.

[Juror 10]: The, the experience of, of how to make judgements and the process of looking at evidence and becoming convinced was important.

[Luis]: And once this trial was over, she only had two days left in the time she was assigned to be a juror, so she thought the court would excuse her and she would be able to go home. But no. They asked her to go to a final meeting with the court… It was to select the jury for a new trial.

And this time, the process was different. The court had called forward hundreds of people. But first they gave them a questionnaire to fill out by hand… and on that questionnaire, in a cold and bureaucratic language, there were a lot of questions about the death penalty.

Questions like this one:

“On a scale from 1 to 10, are you in favor of or opposed to the death penalty?”

Or questions like this one:

“In the case of premeditated homicide, do you believe that the death penalty could be an appropriate punishment?”

[Juror 10]: You have to answer, well, completely honestly.

[Luis]: On her questionnaire, Juror 10 marked 8 on the scale of being in favor of or opposed to the death penalty. I asked her to explain why she answered that way, and she told me:

[Juror 10]: I think… I’m saying: there are times when the people who don’t value life, don’t deserve it. You understand?

[Luis]: In other words, she was… she is… more likely to vote in favor of imposing it.

With that question, she made it to the final round of the selection process. This time she had to participate in an in-person interview. In the courtroom, with the judge, a group of prosecutors, who were bringing forward the case on behalf of the government, and a group of lawyers tasked with defending the accused.

And she was surprised that during the interview, face to face with the prosecutors and the defense, neither one asked her about an aspect of her family life which she had laid clearly in writing…

[Juror 10]: Because I have two brothers who are, uh, who have been on drugs, who were on drugs. They were, they were drug-addicts and, and one of them was in jail.

[Luis]: They didn’t ask her about that, but they did select her to be a juror again.

[Juror 10]: I thought it was odd that I was chosen because of the issue with drugs.

[Luis]: Because of her brothers’ situation.

[Juror 10]: I always said it. I would always say it and well, they always excused me.

[Luis]: She still didn’t know what kind of trial it was going to be, but she had the impression that it was a drug trafficking case.

And, it’s just that, in Puerto Rico it’s very common for drug cases to be handled in federal court. It’s one result of the island’s political status. Being a territory, a colony, the distinction between local and federal jurisdiction sometimes isn’t entirely clear… and the FBI and federal prosecutors have become more and more involved in cases dealing with drugs and firearms.

Of the 94 judicial districts in the United States, Puerto Rico’s…

[María Domínguez]: …Is a unique district, unfortunately, because we are, uh, flooded with drug and firearms cases.

[Luis]: This is María Domínguez, a former federal prosecutor who worked in Puerto Rico for more than 20 years. Domínguez explained that during her time in that role, federal prosecutors reached agreements with Puerto Rican authorities…

[María]: The federal prosecutor’s office in Puerto Rico, uh, took on and accepted and processed a lot of these cases that in other districts would be handled by local authorities. And it was with the exact intention of dedicating federal resources to try and disentangle this problem.

[Luis]: It was the war against drugs in Puerto Rico… but instead of being solved, the problem became much worse. By 2008, an unprecedented crime wave had begun…

In 2009 and 2010, the record for homicides on the island was about to be broken. And in 2011, it was shattered. And authorities indicated that more than 80% of homicides were linked to the drug trade.

[María]: Drugs were linked to firearms, and firearms were linked to violence… It’s a terrible chain. But, yes, we certainly knew that a large portion of the homicides, of the violence on the island, was linked to the drug trade.

[Joe Laws]: Because in Puerto Rico in those years, there’s no doubt that the world was revolcao, “fucked up”, as we say in Puerto Rico. Not “re-vol-ca-do“, revolcao.

[Luis]: This is Joe Laws, a lawyer who was the head of the Public Defenders in Puerto Rico in the 90s and the 2000s. These are the lawyers the federal court assigns to the accused when they can’t afford a private attorney. And no, Joe Laws isn’t an alias… That’s his real name.

[Joe]: And absurd things were happening. You know, I remember a case we had in which a client’s head, a defendant, a person’s head was cut off and they played soccer with it. I mean, they were kicking around a dead man’s head…

[Luis]: Juror 10 was also alarmed by the extent of all the criminality. It was impossible not to be, if you lived in Puerto Rico at the time.

[Juror 10]: And people wanted to do something. What do we do because this is affecting everyone, and I think that resulted in a type of anger, against crime, against criminals, you know. You want to protect your life and your children’s lives.

[Luis]: And there were a lot of cases. So many that when she found out she would be a juror in Alexis Candelario’s trial for the massacre at La Tómbola, Juror 10 couldn’t even remember which massacre it was.[Juror 10]: I must have heard about it, but it was just one more massacre, really, because that happened. That wasn’t the only one, and it wasn’t the first or the last, so…

[Luis]: It was only at the end of the jury selection process that she found out that it was going to be a death penalty trial… And that news brought out conflicting feelings in her.

[Juror 10]: It scares you. It scares you because it’s a person’s life, but… but I was ready to do it.

[Luis]: And here, there is something I need to explain: Puerto Rico is one of the only two jurisdictions in the entire United States where capital punishment is unconstitutional at the local level. In fact, the Constitution of Puerto Rico says…

[Joe]: The right to life, liberty and the enjoyment of property is recognized as a fundamental right of man and the death penalty shall not exist.

[Luis]: Joe knows this part of the constitution by heart…

[Joe]: Well, I thought this was already over and done with!

[Luis]: But no… In Puerto Rico, federal laws supersede local laws… and the death penalty is part of federal law. It is reserved for the worst of the worst… the most violent crimes. María Domínguez explained it to me like this:

[María]: There are crimes that are so horrible that a life sentence is perhaps not a proportionate punishment. If you kill 15, 20 people, 12 people, uh, are you going to have the same punishment as if you killed one person?

[Luis]: Starting in the 90s there was a series of changes to federal laws that were coupled with the increase in crime on the island. So much so, that in the early 2000s…

[Joe]: Puerto Rico became the “death penalty capital” of the US. More death penalty cases were approved in Puerto Rico than in any, almost any other state…

[Luis]: We need to be very clear, approvals do not mean that death sentences are being carried out… What it does mean is that prosecutors were calling for the death penalty more and more.

And yes, it is something that has to be “approved”, through a long and complicated process. Every time there is a case that could become a death penalty case, that case automatically has to be reviewed by a special committee that, in turn, issues a report to the Secretary of Justice, the Attorney General: the general prosecutor for the United States.

[Joe]: And federal prosecutors became obsessed with, uh, getting a death penalty conviction… and winning a case.

[Luis]: The Review Committee on Capital Cases gives its own recommendation, one that can lead to a regular trial with a maximum penalty of life in prison or a trial in which the jurors must consider capital punishment…

[María]: We as a district, give our recommendation. And the recommendation is considered. As I understand it, it’s given some weight, but it is not final.

[Luis]: The general prosecutor of the United States makes the final call.

And yes, Puerto Rico was among the seven jurisdictions most frequently authorized to seek the death penalty.

Joe Laws said that prosecutors went into a kind of frenzy to get the death penalty in Puerto Rico. But María Domínguez says that no, not at all…

[María]: They are difficult cases and I want to tell you that it’s not easy to argue any case in which the death penalty may be imposed. We’re human beings too, but we have a job to do.

[Luis]: Between 1999 and 2011, there were three death penalty cases in the San Juan federal court; the first three trials of this kind in the island’s modern history…

But there was a problem… Puerto Rican jurors refused to give a death sentence. The accused were acquitted… or sentenced to life in prison.

[Joe]: Something else that’s going on in Puerto Rico, juries are used to life sentences, you know? And you thought that was the worst thing that could happen to you…

[Luis]: On a religious and conservative island, those who were serving as jurors weren’t ready to impose capital punishment…

But that didn’t stop the federal prosecutors from trying.

Starting toward the end of 2012, four more capital punishment cases were heard… all in the span of one year. And just for comparison: at the same time, there were only five death penalty trials in the rest of the United States.

And of all the cases being heard in Puerto Rico, there was one that federal prosecutors seemed to be riding on more than the others.

[Maite Bayolo]: Using the Justice Department, they were trying to get someone certified and sentenced to death…

[Luis]: This is Maite Bayolo, a public defender who was on the defense team of the Tómbola case.

[Maite]: And they wanted that someone to be Alexis Candelario Santana.

[Luis]: The logic went like this: the Tómbola Massacre had been so terrible that it would be the case that would finally bring a Puerto Rican jury to sentence someone to death.

María Domínguez was assigned as one of the prosecutors… and she also thought this could be the trial that would change things.

[María]: This case, uh, maybe out of all the cases we’ve seen in Puerto Rico, was the case that most justified the imposition of the, of the most severe penalty, which is capital punishment.

[Luis]: The trial started in February of 2013. Alexis Candelario faced 51 charges. Basically, the State accused him of being the leader of a criminal enterprise dealing in drug-trafficking. What opened the door to the death penalty were the murders committed as part of that criminal enterprise… The nine murders at La Tómbola.

[Maite]: It was like… the theory of the State was vengeance… because he lost the drug point and he wanted it back. That was how the State saw it.

[Luis]: In order to understand the Tómbola Massacre, you first have to understand that Candelario was the owner of the drug point in Los Bravos for more than a decade, until 2003, when he went to trial in a local court in Puerto Rico… Since it was a local case, the death penalty wasn’t on the table.

And in that trial, Alexis Candelario reached an agreement with the local prosecutors to plead guilty to 12 murders, —12—, in exchange for a reduced sentence of 12 years… In other words, one year in jail for every murder.

Once he started serving his sentence, it was reduced even more for good behavior.

After 6 years, Candelario was released from prison.

It seemed unbelievable. That’s why I asked María Domínguez if serving 6 years in prison for 12 homicides is normal…

[María]: There are a lot of us and we don’t know how to answer because those… obviously no… those things shouldn’t happen. Uh, perhaps it’s one of the flaws in the system.

[Luis]: She found it as odd as I did.

[María]: And, well, I can’t judge why they made that decision because I wasn’t there, I wasn’t part of that process. But yes, certainly it is a little shocking.

[Luis]: In the new trial in federal court, the prosecutors argued that the first thing Candelario did after getting out of prison was return to his neighborhood to reclaim the drug point… and that ended in the nine deaths and twenty wounded in the massacre.

[Maite]: Images of the bodies were constantly being displayed in the courtroom using a projector, uh, constantly.

[Luis]: And you need to remember that one of the images they showed regularly was the body of an 8-month-old fetus.

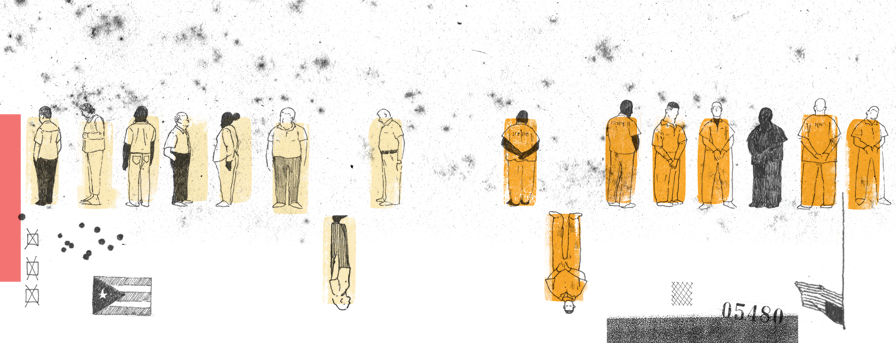

When the trial began, each of the twelve jurors was assigned a number to protect their identities. And prosecutors quickly presented an image of Alexis Candelario as a criminal mastermind.

Again, here’s Juror 10.

[Juror 10]: They presented evidence mainly about, about the homicides. They set you up to think that, that this guy is a monster.

[Luis]: There were days Juror 10 left the trial feeling completely exhausted. When she got home she would say to her husband…

[Juror 10]: I swear, I would kill him. The guy’s a monster. Do you understand, really? How could someone do that! But other days, well, I came home, and I was completely silent, like I was in reflection. I came home reflecting.

[Luis]: It was an intense process… The twelve jurors had to analyze evidence that was very difficult to parse… impact reports from the bullets in the bodies and the wounded… witnesses talking about the relatives and friends they had lost or the horror they experienced that night in La Tómbola.

Every morning, the jurors would meet in a small room next to the larger courtroom. And little by little, Juror 10 got to know the rest of the jurors. There was one who…

[Juror 10]: Worked for the Electric Power Authority, another was a salesperson, another one owned a tattoo shop, there was a social worker, I think one was a retired teacher, uh, an older woman who was like a homemaker, uh… there was a student…

[Luis]: Seven women and five men… college students and retirees… salary workers and business owners… from the owner of a small business to Juror 10 who works for a company that manages millions of dollars. It was a rather diverse mix.

And even though the task at hand was heavy and even macabre… a sense of camaraderie began to surface among them.

[Juror 10]: And, well, every day, we would decide who was going to bring the bread, the ham, the cheese; we would make breakfast, see, among ourselves and sometimes even the judge would stop by to grab a quick coffee that he would take with him.

[Luis]: They listened to nearly 70 witnesses in a little over a week. They evaluated more than 700 pieces of evidence. Three witnesses claimed to have seen Candelario in La Tómbola that night… firing indiscriminately into the crowd. These testimonies were key for Juror 10.

It wasn’t a difficult decision. The jury retired to deliberate and they issued a unanimous verdict that same day…

[Juror 10]: I believed the whole time, with the evidence that was presented, that, yes, he was guilty.

[Luis]: Guilty. Of all charges.

[María]: A stunning decision because it came so quickly.

[Luis]: And if this had been a trial like any other, it would have stopped there. But death penalty trials are different. They have two parts… and the second was still missing, the sentencing phase, where the jury has to decide between life in prison… and a death sentence.

And in the second trial the prosecutors argue in favor of the death penalty for the person who has already been found guilty. And the defense presents an argument in favor of life.

[Joe]: And all of that is thrown together so the jury can determine if he deserves to be killed.

[Luis]: An entire additional team comes in for the second phase.

[Joe]: The defense is allowed to present what we call extenuating circumstances. And here we’re talking about if there was alcoholism in the family or if he was a drug-addict… and maybe that lessens his responsibility. Maybe.

[Luis]: In Alexis Candelario’s case, that was up to Maite Bayolo… who was part of the mitigation team.

[Maite]: The goal for me is, uh, to convince a jury that this person is human. Obviously, well, legally it’s to convince a jury that he doesn’t deserve the death penalty because there are more mitigating factors than aggravating factors… and it’s like a battle.

[Luis]: Aggravating factors. That is the part that’s up to the prosecution in this new chapter of the trial.

[Joe]: This is not the first time he’s killed someone… he’s killed two people…or three.

[Luis]: The prosecution focused on…

[María]: …This person’s extremely violent and reiterative behavior, the fact that he appeared to have no conscience and did not value human life. Maybe just for his own… or maybe not even his own.

[Luis]: And for that reason, that the only correct and just decision for Alexis Candelario was a death sentence.

[Daniel]: When we return, the jury has to decide if Alexis Candelario will receive the first death sentence in the modern history of Puerto Rico.

[Ad]: We’d like to say a quick thank you and share a message from one of our sponsors, Sony Music Latin, presenting Grammy Award winning artist, iLe, a Puerto Rican singer and composer known for her work with Calle 13. Her debut album “iLevitable” garnered her a Best New artist nomination at the Latin Grammys and subsequently won the Award for Best Latin Rock, Urban or Alternative Album at the 60th Annual Grammy awards. Her new single and video titled “Odio” is available everywhere now.

[Ad]: Support for this NPR podcast and the following message come from Sleep Number, offering beds that adjust on each side to your ideal comfort. Their newest beds are so smart, they automatically adjust to keep you both sleeping comfortably all night. Find out why nine out of 10 owners recommend it. Visit SleepNumber.com, to find a store near you.

[Daniel]: If like me you follow US politics, I assume you are dizzy trying to understand what happened, that tweet, this scandal, the upcoming elections, etc. It’s not easy. I offer a solution: the NPR Politics Podcast. A smart conversation that goes beyond the headlines. On NPR ONE or wherever you listen to podcasts.

[María Hinojosa]: Hi, it’s Maria Hinojosa. Host of NPR’s Latino USA. What do you think? There’s almost 60 million latinos and latinas in the US. We document those stories and those experiences each week. Find us on the NPR One app or wherever you get your podcasts.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, Juror 10 and her fellow jurors were entering the second phase of Alexis Candelario’s trial. It was just 10 days after the trial where they had unanimously found Candelario guilty of the killings at La Tómbola.

Luis Trelles continues the story.

[Luis]: For this second phase…

[Juror 10]: …They brought in relatives of the victims, like the baby, and then, well, it was a short trial. It lasted I think about two weeks or less.

[Luis]: The prosecution brought forth several people who were affected by Alexis’ crimes. They were heartbreaking stories… of ruined lives… María Domínguez remember one witness who came to talk about the night her daughter was killed at La Tómbola.

[María]: And she said, uh, that when her daughter died, she felt her heart being pulled out, that someone reached into her chest and grabbed her heart and she woke up and called her daughter right away but she didn’t answer. And then we learned, you know, that it was approximately at the same time when her daughter was shot in the head and died.

[Luis]: The defense focused on presenting the part of Candelario’s life that the jurors didn’t know about.

[Maite]: This is a boy who basically grew up alone. We see it in Puerto Rico all the time. This boy grew up next to a controlled substances, a drug point. A boy who saw, who witnessed, as it was brought forth at the time, a lot of acts of violence… A boy who grew up seeing dead bodies on the ground.

[Luis]: It was an environment where there was no support from his family… but that wasn’t all. The State was also absent. The social workers who work with minors in cases of extreme negligence never came to his house. Alexis stopped going to school. No teachers followed up with him at his house. No one asked why he had stopped going to class.

[Maite]: At that time, there was el Palo de Goma, this famous spot on la Calle Los Magos…

[Luis]: El Palo de Goma… was a sale point for heroin, cocaine crack and marijuana.

[Maite]: Which was literally a tall rubber tree, right by… six feet away, more or less, from the place where Alexis grew up, which was a small one-room house… with 10 siblings… and his mother.

[Luis]: David Ruhnke, an American lawyer specializing in capital punishment, was in charge of the defense’s final arguments. And he concentrated on giving an exact definition of what a life sentence is. It means spending the rest of your life in prison, where the condemned person’s existence is confined to a shared cell… the size of a restroom… the rest of the time is spent with hundreds of other inmates… most of which would be in prison for murder and rape. It’s the kind of place you can only leave in a coffin…

What Ruhnke was arguing was that this punishment is sufficient. It’s enough. He asked the jury not to let the death penalty come to Puerto Rico… as though he were asking them not to open that door.

After Ruhnke, it was María Domínguez’ turn to give the prosecution’s final rebuttal.

[María]: Well my job was to make that the jury understand that a capital punishment was the only proportional and adequate punishment for all the behavior that had been attributed to Alexis Candelario, so, well, that response, uh, was leading to that, right, that the shroud of death had already visited the island in the form of Alexis Candelario.

[Luis]: When the final arguments were over, the jurors returned to the jury room for deliberation. They had been meeting there for nearly two months and each of them already knew what seat to take around the table.

[Juror 10]: And normally when you pick your seat in the beginning, everyone else respects that area, you know, when you go back to it, we’re like horses in a stable.

[Luis]: Each jury chooses a president who is in charge of leading the deliberation. In this jury, the president called a yes or no vote on whether or not to give Candelario the death penalty. They were going to vote out loud. The jurors went in order around the table.

[Juror 10]: …And they started with the student, after the student was the tattoo guy. Maybe they said… some of them said “yes” because they were convinced or because he’s a monster or whatever reason, but they were blunt. They were curt.

[Luis]: Juror 10 was the fourth to go…

[Juror 10]: But I said no.

[Luis]: No one was expecting that answer. Juror 10 could tell how surprised the group was. That’s why she explained that as far as she was concerned, Candelario…

[Juror 10]: …Had been failed by his mother, by his family, by the Department of Education, by the Department of Justice of, of Puerto Rico. That’s one, one of the serious responsibilities that exists at all levels. And we’re there. We’re all there.

[Luis]: It was an argument that had been made in the trial. As part of the mitigating factors, the defense had put forth the same idea: the system had failed Alexis Candelario since he was born… and that was something that had to be considered before imposing the death penalty.

It’s really an argument about the injustice of applying that punishment in an imperfect society.

The defense lawyers often say that rich people never get sentenced to death. And they have a point. It’s a punishment that’s overwhelmingly applied to the poor.

We have to remember that this isn’t an argument to exonerate a person who has already been found guilty… or to absolve him of his responsibility for the deaths and the lives he has ruined forever. But in an imperfect system, is it really just to apply the maximum punishment to someone who grew up suffering the neglect that Alexis Candelario experienced?

It’s a question that each juror debates in his or her own conscience.

And even though it was surprising, even to herself, Juror 10 came to the conclusion that Candelario didn’t deserve to die.

[Juror 10]: And as long as there are imperfections and as long as a whole array of, of entities fail, there should never be, we should never arrive, arrive at that verdict, you understand? It has to happen in a perfect State.

[Luis]: We have to remember the questionnaire the court gave out before the trial. On that questionnaire they had been given a scale from 1 to 10… One meaning she would never impose the death penalty, not even for the worst crime. Ten meant she would impose it almost automatically against any person accused of premeditated murder. On that scale, she put an 8.

[Juror 10]: When they asked me about violence, well, I answered in anger, that yes, if I can help to get rid of a criminal I’ll do it, but that wasn’t the case. It isn’t.

[Luis]: Once she finished explaining her position, the president of the jury…

[Juror 10]: Well, he was more, more condescending, in a word, and said: well, now everyone finish up and then we’ll come back and have another round of votes.

[Luis]: There were 8 jurors left… and all of them gave the same answer. They all said yes to the death penalty.

[Juror 10]: They gave reasons why, you know? He killed so many people. He’s inhuman. He’s cruel. It’s like… I mean, they gave reasons and, and they were good reasons, because it’s true. Everything they were saying is true. He did it. If you are presented that evidence and you believe it, well, then he did it and you need to judge him.

[Luis]: Juror 10 was on her own.

[Juror 10]: I was surprised that there wasn’t at least another person… I expected at least three people to disagree.

[Luis]: The president of jury called a second round of voting. And it was clear that everyone would try to convince Juror 10 to change her vote.

The death penalty can only be reached through a unanimous vote. One juror out of 12, even if there’s a super majority of 11 votes, automatically results in a life sentence.

And that was when the camaraderie that the group had created disappeared completely. The others tried to convince her… but something had hardened in the group.

[Juror 10]: I was surprised that two or three people were even intimidating.

[Luis]: They weren’t talking to her the same way they had before…

[Juror 10]: That’s when I said, “Hold on”, but they were already making comments under their breath and giving me dirty looks, you know? Because, a lot of times there’s an eloquent silence… there are eloquent silences that speak to you, you know, like the looks and a kind of discomfort.

[Luis]: One of the jurors was an employee at an electrical company and worked not very far from La Tómbola. At one point during the deliberation, he started crying and told her:

[Juror 10]: “Please, look, I work at the electrical power and that guy is going to kill me. You understand?” Like they were so afraid.

[Luis]: During the trial, the prosecutors had painted an image of Candelario as a criminal mastermind. Bruce Hegyi, a prosecutor specializing in capital punishment cases who had come from Washington, repeated several times that Candelario could kill again… even if he was locked up in jail… some jurors were afraid of retaliation from Candelario. And that’s why they wanted a unanimous vote to impose capital punishment, to protect themselves. And since Juror 10 wasn’t willing to change her mind, the worker at the electrical company was putting all of the responsibility for whatever could happen on her.

[Juror 10]: And I was saying: nothing’s going to happen to you. Don’t think about that. I told him: don’t think about that. It’s not going to happen.

[Luis]: And then several of the jurors started doing something the judge had warned them against doing…

[Juror 10]: And yes, that’s what they said. They said it themselves that they wanted to, you know, send a message…

[Luis]: …They wanted to use Candelario’s trial to send a message to all the criminals in Puerto Rico. In other words, deliver a sentence based on criteria that went beyond the case itself.

In the second round of voting, Juror 10 spoke again… and this time she tried to convince the others that a life sentence in prison was a just punishment.

[Juror 10]: Because, the judge explained it: It’s life in prison, he leaves jail dead. Don’t you think that’s punishment enough?

[Luis]: And then she gave the most intimate argument of all. She had had two brothers who were addicted to drugs and both had spent time in jail and in rehab centers.

[Juror 10]: And in this trial I learned how a drug point works. I didn’t know that, but I do know the areas you can’t go… where people gather at night. You know, uh, everyone knows where their own Palo de Goma is.

[Luis]: It’s wasn’t her world, but she had seen her brother’s sad trajectory and saw part of her brothers’ lives in Candelario’s path… She had seen firsthand the ineffective rehab centers and prison sentences that sometimes made people’s addictions worse.

[Juror 10]: And if anyone could be angry at any drug lord, that was me because they sold drugs to my brothers and they prey on the, the weak and they don’t care, you see. They get rich from it…

[Luis]: You don’t hear arguments against the death penalty like Juror 10’s a lot in Puerto Rico. Generally, the people who oppose it do so for religious reasons. But in her case, it was personal experience.

[Juror 10]: I don’t belong to any religion. Those were my values and my principles. They were present. But not in a religious sense.

[Luis]: The deliberation lasted two days. It was 11 against 1.

All of them at the same time… demanding that she vote in favor of the death penalty for Candelario.

[Juror 10]: What made me cry, was that I felt pressured and I had this feeling of powerlessness, of not being able to properly express how I, how I interpreted the situation. It was a feeling of not being able to make myself understood.

[Luis]: The weight of the decision was becoming too much for Juror 10 to bear. It was as if she was being fenced in… and she was looking for some space to reflect in peace.

[Juror 10]: Because you say, damn, when so many people are saying that, well maybe I’m wrong… what, what side of this am I not seeing, you know?

[Luis]: So…

[Juror 10]: That’s why I went, I went to the bathroom and I asked for wisdom… and I sobbed, I sobbed, I cried uncontrollably.

[Luis]: She spent more than two hours locked in the bathroom. She didn’t know what to do. She was sure that Candelario didn’t deserve the death penalty… but she felt like she didn’t have the strength to face the other jurors.

[Juror 10]: …And I felt like I wasn’t going to be able to take a third round of voting… I couldn’t. I mean, I wouldn’t have had that… maybe I would have given in.

[Luis]: I was at the court the day they read the verdict. I can remember perfectly when the jury entered the courtroom to hand over the paper with the final decision to the judge.

[Juror 10]: And it was very intense because, if you were in the room, there was this sepulchral silence, an incredible silence, I had never heard a silence as, as powerful as that…

[María]: I think there was an expectation that they were going to impose the dea-, capital punishment… and maybe that was the reason it felt so tense.

[Luis]: The courtroom was full of journalists… and also relatives of the victims and people from Sabana Seca.

And those who weren’t at the court were waiting for the verdict in the neighborhood.

Mariana, the voice we heard at the beginning of the episode was one of those people and she remembers what people were saying in the streets of Los Bravos.

[Mariana]: I heard comments from people who knew people who died there and a lot of people said: yes, he does deserve it and that well, he didn’t have feelings and that he was a bad man… Yes, a lot of people felt…. that, that, that he should die.

[Luis]: The rest of Puerto Rico was waiting too… and almost everyone was convinced that this was going to be the first death sentence in 75 years.

Maite Bayolo, from the defense team, was in the courtroom, along with Candelario’s family… and she could also feel the tension in the room…

[Maite]: I’ll never forget the judge’s reaction when he read that paper… uh, it was like an expression of dissatisfaction.

[Luis]: Life in prison.

María Domínguez, the prosecutor, immediately looked at the jury to see their reactions.

[María]: It was clear to me that they were upset. Some of them were making fists… Uh, and from their expressions, I could tell, you know, that a lot of jurors were upset with the decision.

[Luis]: I asked Maite Bayolo what she felt when she heard the verdict.

[Maite]: Relieved. I was happy. Great. Well, it was a big win, because despite the fact the client was going to prison, he won. He won his life.

[Luis]: Candelario had been saved and in the process the first death sentence imposed in Puerto Rico by a federal court was avoided.

The judge thanked the jury and finally dismissed them from the court.

To avoid attention from the media and protect their safety, the jurors in death penalty trials park their cars at a secret location that’s far from the court. During the trial, a bailiff is in charge of picking them up every morning and accompanying them back at the end of the day. After the final verdict, the jurors took that trip for the last time.

[Juror 10]: No one spoke to me. No one, no one, no one spoke to me, and it was a silence like… you could hear a pin drop… that’s how it was. And no one said goodbye to me, you know. No one, and everyone was like angry.

[Luis]: And that was the last time they would see each other.

The news went out that same day: a single juror had prevented Alexis Candelario from receiving the death penalty.

The president of the jury gave an interview to a local newspaper to express his frustration with the verdict.

Another member of the jury spoke with Univisión, placing all the blame on Juror 10.

(Soundbite Juror on Univisión)

[Juror on Univisión]: If she was so contaminated, uh, by her personal experience with her brothers… that if, that if they kill this man, what will happen to my brothers… I’m opening the door for my brothers or one of my brothers, I don’t know, she was thinking something like that… and I really respect that situation, but I would have set all that to the side.

[Luis]: She was suggesting that Juror 10 refused to vote in favor of the death penalty to somehow protect her brother in prison, which Juror 10 denies.

[Juror 10]: There was a woman who, I think, went on Univisión to tell lies because she said so many lies. She said…. Because of one, you know, because of one we’re not going to… you know?

[Luis]: She also described the tense atmosphere during the deliberation and spoke specifically about Juror 10…

(Soundbite Juror on Univisión)

[Juror on Univisión]: There were jurors who called her out by name… uh, with intense, key words and… but she erupted in tears. Her crying was very annoying.

[Luis]: And the criticism didn’t just come from people who were involved in the trial. They were also on social media, TV, the comments sections of newspapers… the national conversation centered on what Juror 10 had done.

[Juror 10]: They said they hoped someone killed my son or daughter or mother, you know? It was… it was really ugly, and I said: Good Lord! I was doing my job, you know.

[Luis]: The verdict in the court of public opinion was categorical. Juror 10 had been weak… incapable… Her inability to vote for the death penalty had set back efforts to combat crime in Puerto Rico.

It’s impossible to measure the impact a single trial can have, but it seems unlikely to me that this case had an encouraging effect on criminals in Puerto Rico.

Juror 10’s decision did have an unexpected effect in other areas. In July of 2013, about the months after the trial ended, the Attorney General at the time, Eric Holder, stated that only the most severe cases would be approved to proceed as death penalty cases in Puerto Rico. After six attempts and 14 years, they hadn’t managed it. And the general feeling was that if they couldn’t manage it in Candelario’s case, they’ll never be able to.

For Maite Bayolo, concerning this case…

[Maite]: The position on the death penalty changed. The position on certification changed. I know it changed and it stopped happening in Puerto Rico…

[Luis]: Essentially. After that year there were no other death penalty cases in the federal court in San Juan… until now.

The next chapter in Alexis Candelario’s long and violent story starts immediately after the end of the trial. Alexis appealed the guilty verdict… and in the process, an issue arose. A big problem.

It turns out a key witness, one of the three people who identified Alexis Candelario in La Tómbola the day of the massacre, was afraid to speak openly in court in front of Alexis… and in front of all of the journalists who were there to cover the case.

[María]: And the judge presiding over the case allowed him to testify late in the afternoon, so that there wouldn’t be anyone watching.

[Luis]: Basically, the judge in this case gave the order to finish that day’s work before the witness came into the courtroom… the journalists and the audience left… and then the judge had the jury come out to the empty courtroom to hear the witness. Candelario’s defense team argued that the judge had deprived their client of his right to a public trial.

In 2016, a panel of judges that deals with appeals in cases in Puerto Rico, the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston…

[María]: …Ruled it a procedural error, since trials are open etc. And, and, no… In other words, the repeal had nothing to do with the merits of the case. It was a technical contestation.

[Luis]: They repealed Candelario’s conviction and sentence.

And because of this technicality… Alexis Candelario is about to face another death penalty trial.

The strange thing was that he himself decided not to accept the life in prison sentence he received and that is very odd. People who get out of a death sentence usually don’t want to give prosecutors a second chance at it.

I asked Maite Bayolo…

[Luis]: Do you know why he decided to appeal?

[Maite]: No, I don’t know. I mean, what I can tell you is that when someone gets a life sentence, it’s seen as a win. You don’t appeal.

[Luis]: Juror 10 has also heard that Candelario’s cases is going to be heard again.

[Juror 10]: I think it’s going to cost the people too much money, because they already have a, they have a guilty verdict, you know? But if they’re going to do it all again, the prosecution is going to insist on that, I think that… I hope justice shines as it should. Not how I think, but, how it should.

[Luis]: Despite the judge’s error, Candelario could have accepted the original ruling. After having studied the case closely, it seems very unlikely to me that a new jury will find him innocent of the Tómbola Massacre.

Now his case is going back to court, and once again it is challenging Puerto Rico’s ideas and attitudes toward capital punishment. When the new trial starts, the court, the prosecution and the defense will have to choose another 12 citizens to serve on the jury. They’ll give them forms, they’ll interview them in the courtroom, they’ll ask them if they believe they’d be capable of issuing a death sentence.

And no one knows if among those selected, there will be another juror like number 10.

[Daniel]: Alexis Candelario’s new trial is scheduled to start on 2019.

Luis Trelles is a Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan. This reporting is possible in part thanks to the support of the Soros Justice Fellowship.

This story was edited by Camila Segura and me. Music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

We’d like to thank Víctor Román, former director of the Puerto Rican Coalition Against the Death Penalty; Judge Aida Delgado of the Federal Court for the District of Puerto Rico; and Carla Minet, Director of the Puerto Rico Center for Investigative Journalism.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Jorge Caraballo, Patrick Moseley, Ana Prieto, Barbara Sawhill, Laura Rojas Aponte, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Silvia Viñas and Luis Fernando Vargas. Our interns are Lisette Arévalo and Victoria Estrada. Carolina Guerrero is our CEO.

Every Friday we send out a newsletter where our team recommends movies, music, series, books, and podcasts that inspire us. It has great links for you to enjoy during the weekend. You can subscribe on our website by going to radioambulante.org/correo. Again that is radioambulante.org/correo. If you use Gmail, check your promotions folder and drag our email to the main inbox so you won’t miss it.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Learn more about Radio Ambulante and about this story on our website: radioambulante.org.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.