Translation: When Havana was Friki

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

Daniel Alarcón: Now you can take Radio Ambulante with you wherever you go with the NPR One app. NPR One offers the best from public radio: music, local stories, and your favorite podcasts. NPR One joins you while you drive, prepare dinner or tidy up the house. Find NPR One in your app store.

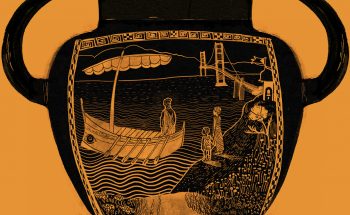

Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Now that we are part of NPR we want to share some of our favorite stories with our new audience. Today we go to La Havana.

María Gattorno: Well, a friki was… they were rock music fans.

Dionisio Arce: Frikis were actually fans of gringos.

Juan Carlos Torrente: You have a look, a rock metal look. In other words, you have long hair or you are shaven headed, you have a mohawk or you’re into safety pins, you dress in black, you wear t-shirts with bands of that genre, then you are a friki. You understand?

Daniel Alarcón: Perhaps listening to metal music in the 80s and 90s wasn’t something out of the ordinary in many Latin American cities. But in Havana…

María Gattorno: Look, I think you had to be crazy if you were a rocker during that time because you had to face a world where everything was against you.

Daniel Alarcón: Today, “When Havana was Friki.” From Cuba, Luis Trelles tells us the story.

Luis Trelles: To understand the story of the frikis in Cuba, you first have to understand that after the revolution, everything in the island received an ideological burden. Even the music. It was the 60s, and rock was seen as the enemy’s music. Even so, people found a way to listen to whatever they wanted. One of them was…

Dionisio Arce: My name is Dionisio Arce Cans. I’m the singer and director of the band Zeus. I’ve been in charge of running the most legendary metal band in the country for the past 25 years.

Luis Trelles: But before being the singer of the band, when he was a teenager, Dionisio discovered the music he loved like this:

Dionisio Arce: We had radios that came with modulated frequency and you could pick up all the American stations through their antennas. So all the young people would go to the beach and turn on the radios to could listen to American music.

Luis Trelles: It was 70s. People listened to a mix of funk, progressive rock and even disco: bands like the Bee Gees, KC & The Sunshine Band and Emerson, Lake and Palmer.

Dionisio Arce: It was what we listened to, and it was prohibited at the time. You know how young people are: you ban something and that’s what they are going to do the most.

Luis Trelles: By the 80s, disco music was dead, and a more aggressive sound from bands like Metallica and Megadeath started playing on the island.

Dionisio Arce: Generally, all young people were into metal. It was then that I discovered that music. I liked it, I understood it, I sympathized with it, and I stayed with it. Even today, I don’t listen to anything that isn’t heavy metal.

Luis Trelles: It was the start of the metal scene in Cuba, and with it, a new counterculture of youth known as the “frikis” was born. This is a broad label, hard to define. Dionisio says that in the beginning…

Dionisio Arce: The frikis were only young people who listened to rock music and dressed different from the others. For example, they would tighten their pants and wear tight t-shirts.

Luis Trelles: Little by little, the style became more extreme, until the term “friki” was associated with longhaired metal heads and their love for decorative skulls. Juan Carlos Torrente carries the name with pride. He is the singer for the death metal band Combat Noise, and this is how he defines himself:

Juan Carlos Torrente: I’m a friki, friki. I walk down the street and everywhere I go, I’m myself: with my hair down, or in a ponytail, dressed in black, with my boots. And I’m a friki, you know?

Luis Trelles: But in the 80s, just dressing like that put you at risk.

Dionisio Arce: They would arrest you for no reason: for wearing tight pants, for having your hair a little bit longer –not that long like I have it now around my waist. If you had it shoulder-length, they would arrest you and try to shave your head. And there were times they did it.

Luis Trelles: Despite the harassment, the metal scene kept growing, fueled by the albums of foreign bands that were shared from person to person.

Juan Carlos Torrente: If someone came from the United States, they would bring me four cassettes of Testament, Slayer… and then I would be the only one to have them. But without really noticing it, we all understood we had to distribute the music among us.

Luis Trelles: That exchange brought the frikis together and helped them take the next step.

Juan Carlos Torrente: So then the music inspired you to create bands. If you are a friki and a metal head and you enjoy music, you say, “I have to start a band.”

Luis Trelles: For the newly formed bands, finding a place to perform live was an impossible task. There was no space for metal in clubs or concert halls. The only alternative was to play…

Dionisio Arce: In house parties that could also be shut down by the police because it got so loud. They would come and end the party, “you can’t play anymore. Pick-up your stuff and leave.”

Luis Trelles: They would accuse the frikis of “ideological diversionism”. In other words, their music represented a deviation from the country’s socialist values.

Dionisio Arce: And even more so in a social system where everything happened around trova music, contemporary popular music and traditional music.

Luis Trelles: The revolution wanted to create a new, well-dressed man in an ironed guayabera. A man that listened to this.

The frikis, on the other hand, roamed the city turning the volume up on this.

With very few places to play and without being able to dress without putting themselves in danger, the frikis were left with no options. Until the movement found a key person.

María Gattorno: Well, my name is María Gattorno. Eh, my story is a bit longer.

Luis Trelles: María was not a metal fan. On the contrary, she was a 37-year-old bureaucrat with delicate features and soft manners, who coordinated one of the city’s community centers with very conventional programming.

María Gattorno: There were nights when people could dance danzón, groups would perform, and there were balladeers and trovadores, as I told you.

Luis Trelles: The rockers, however, had a different perspective.

Dionisio Arce: Everyday, the only thing that people did in the community center was play dominoes.

Luis Trelles: One day, near the end of 1987, María was working in the center when someone knocked at the door. When she opened, she found three teenagers wearing t-shirts with American bands and torn-up jeans. They asked her:

María Gattorno: “Is this a Casa de la Cultura [community center]?” “Yes,” “Who is the person that gives out the spaces?” “Ah, me. Let’s talk.” “Well, we are a rock band.” “Ah, that’s great, really interesting. And where do you rehearse?” “Well, in a park near that hill over there.” “Ah, what do you mean in a park?” “Yes, that’s why we came because they are going to kill us. They suggested we look for another place to rehearse. We can’t do it in our houses; there’s no space. Our parents don’t understand us, and someone told us about this community center, and we happen to get here by chance.”

Luis Trelles: María understood perfectly well. 20 years before, she had secretly listened to the Beatles, and she remembered all the friends that had been arrested for having long hair. That’s why she didn’t hesitate to help the boys that were now reaching out to her.

María Gattorno: And they still had their long hair, and they wanted to keep playing the things they liked. And if it was rock, then let’s play rock. And it would’ve been atrocious to say no to them.

Luis Trelles: Once the first band came in, a second one came, and then a third one. They came from all corners of the city, from places that María had never heard of before, and that caused her great curiosity.

María Gattorno: I wanted to know who these young rockers were. And there were so many bands. “Let’s do a rock scene, why not?” So I sought them out to spread the word that I wanted to do a meeting with all the rock bands in the city. And they came.

Luis Trelles: In that meeting, María proposed the idea of creating a space for them in the community center. They wouldn’t have to rehearse in the park anymore. At the center they would have a regular practice schedule and one night a week for concerts.

María Gattorno: They laughed at me, “but… ah, that won’t happen. But…”

Dionisio Arce: There was no stage. It didn’t have anything. The house was really shabby, it needed a paint job. It wouldn’t do.

María Gattorno: They were all like: “this lady is crazy.”

Luis Trelles: The bands were so used to things being difficult, of being thrown out from everywhere, that they only saw the obstacles.

María Gattorno: “I have the instruments in Arroyo Naranjo, how am I going to bring them all the way over here?” “Well, you rent a van…” “But a van won’t go there, there won’t be any gas.” And yes, yes it was hard, they were right, but I was right too. Both of us were right, but in the end I won.

Daniel Alarcón: We’ll be back after the break.

–MIDROLL–

Hey, before going back to our story, if you want to follow up closely all the changes that are going to happen in Washington, I recommend you to listen to the NPR Politics Podcast. They are now launching two new episodes every week to keep you informed about what’s happening and what it means. Subscribe to the NPR One app or go to npr.org/podcasts

Before the break, María Gattorno had offered the rockers from La Habana a place where they could rehearse and play their music. Luis Trelles tells us more.

Luis Trelles: The community center was far away from the colorful seaside malecón and Old Havana. It was in the Timba neighborhood, where you don’t see classical cars from the 50s, but old Russian models that had been patched up with rusty replacement parts. This was a marginalized community where older people sat on the sidewalks with their portable radios, listening to salsa.

And the cultural center stood in a corner of this neighborhood. It’s house a little bit bigger than the other ones, and that makes it different. It also has a façade full of columns, which gives it the image of a grand old hacienda, and a big rectangular cement patio on one side.

It was there that the first concert took place in 1988.

María Gattorno: The patio was baptized with blood on September 17, the day of Saint Lazarus. Iconic. There was too much anxiety. There were a lot of expectations, it was… the rock scene of the aficionados, of the rock music followers, was very fractious and very orthodox. “I’m a fan of this group or of that style, and those people are retards because they don’t listen to the music correctly. They don’t understand me and they don’t know anything.”

Dionisio Arce: There were different manifestations because there was punk, symphonic, heavy metal, hard rock, trash, death metal… everything was there.

Luis Trelles: Plus the people from the neighborhood, who felt invaded.

María Gattorno: “And what are these people doing in my territory?” And it got ugly.

Juan Carlos Torrente: The concert ended in a giant fight, a spectacular fight with the locals.

María Gattorno: It came to blows, it was a terrible brawl.

Juan Carlos Torrente: I ended up with three machete cuts, 36 stitches that left a permanent reminder of my first night in María’s Patio.

María Gattorno: I thought it was the end. I spent three days in bed with my head covered, “I failed, utterly.”

Juan Carlos Torrente: But after that, everything went back to normal. The contending forces faced each other, you know? Suddenly, we joined forces. We communicated and, at the end, we all became friends.

Luis Trelles: After that, there wasn’t another weekend without a concert, no matter how hard it was to get the instruments. In an island known for its shortages, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 90s, the bands would play the drums made out of X-ray prints and phone cables that replaced guitar strings.

Juan Carlos Torrente: We played with Russian guitars, German guitars and electric guitars from the Socialist Block—old and horrible. It was terrible. Sometimes bands would disappear because their guitar strings would break or they wouldn’t have amplifiers. Or the speaker would break. And it was fixed, but then the amplifier would break, and then there was no way of getting another amplifier, or there weren’t microphones to sing. So it was very very hard to start a band here.

Luis Trelles: All the music that was played inside the patio fell under the general rubric of rock, but what was heard the most was metal and punk. And they would sing in Spanish.

In English.

And in the universal language of death metal.

The center’s official name—La Casa de la Cultura Roberto Branley — was slowly forgotten. Now, it was simply called El Patio de María. The outside walls were covered with graffiti, a small open-air stage was built and a sound system was installed. It wasn’t much, but by the beginning of the 90s the frikis finally had a place in the city’s cultural life.

It was in that decade that the community faced a new enemy: AIDS. An epidemic that affected many people in the island but it hit the frikis particularly hard.

Juan Carlos Torrente: It was a horrible thing when AIDS got to Cuba, right? I have terrible anecdotes of that time, because the rockers suffered so much, and many friends died from AIDS. A lot of colleagues that hanged out with me.

María Gattorno: In Cuba, the word out was that there were many cases, but most of them weren’t covered by the media. I’m talking of 90, 91. That’s when I learned the reality of this phenomenon.

Luis Trelles: The reality was simple: an epidemic was spreading throughout the entire island. And young adults, ages 15 to 21, had a higher risk of contracting it. Public health officials looked for a way to reach them. In that search, they found hundreds of frikis with a very active sexual life in Maria’s patio.

Juan Carlos Torrente: We all had sex without condoms. I imagine that the whole world did. Everyone had sex without condoms.

Luis Trelles: Maria came up with the idea of bringing all the rock bands together to create a support and prevention program called Rock Against AIDS.

Dionisio Arce: It was an incredible thing. The donations at Maria’s Patio by bands donating for the sick, and rock concerts that raised 15 thousand pesos.

Luis Trelles: The Patio filled up with sexual education materials, especially contraceptives, which arrived in industrial quantities. An entire generation of frikis was learning to have safe sex.

María Gattorno: Look, the condoms were given a special label, condoms in specific colors. I was the one with the task of saying, “hey, leave the red ones for this person or the black ones for this other, and if there’s yellow condoms, they are for this other person.”

Luis Trelles: Rock Against AIDS lasted four years and its success gave Maria an opportunity to experiment. She witnessed the changes that could be achieved at the center, so she expanded the program to include people with alcohol and drug problems—especially pills, the most common drug among the frikis. But this time it was different because the government’s opinion was clear: there was no drug problem in Cuba.

María Gattorno: They said that if you talked about addictions, you would get the youth interested in those types of drugs, and instead of discouraging consumption, I would incentivize it.

Luis Trelles: María was used to finding resistance, but she had never been forced to shut down one of her initiatives completely. Even though she fought to keep it going, in the end the anti drug program was shut down. At the same time, Maria’s Patio was still as popular as ever. Maybe that’s why the end took everyone by surprise.

Juan Carlos Torrente: There came a time when people didn’t even fit inside the center. It was completely full with kids playing as loud as possible, full of longhaired frikis. They called us the black tide, imagine that. And suddenly they closed El Patio de María.

Luis Trelles: The closing was so abrupt that there’s still several theories as to why it happened. Maybe it was the location. The community center, and La Timba, were only a few blocks away from the Plaza de la Revolución—so the Patio was the noisy neighbor right next to the center of government. Many metal fans think that the authorities wanted to reform the entire neighborhood.

Drugs also played a role. It was ironic: María was forbidden to continue her prevention program and then the center went through and antidrug police raid. María and the frikis fought to keep it open, but nothing worked. Later on, Dionisio talked with a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Culture, and asked him the question what was on everyone’s mind: why?

Dionisio Arce: And he told me, “I can’t give you an answer, but the decision came from upstairs. So forget about the Patio, Dionisio.”

María Gattorno: For me, it felt like they took away half my life. It had been my life’s work. I had dedicated so much to it. All the work from my youth. And I hit deep, deep rock bottom, and I turned away from everyone and everything.

Luis Trelles: The closing culminated a cycle that had started 15 years earlier with the first Patio concert, and the Havana frikis were once again without their own space.

Patio resident: Sit down.

Luis Trelles: Where are we?

Patio resident: Look, we are in Maria’s Patio. An old courtyard of fun, rocker things, this is the La Timba neighborhood patio.

Luis Trelles: This is one of the center’s new residents, which now serves as a homeless shelter. The community center is no longer here, but there are still people from all over who make a pilgrimage looking for it. Like me. I’ve come all the way from Puerto Rico following the story of the frikis.

Patio resident: But not only you, Luis. Other compañeros, others… we won’t call them foreigners. Colleagues, because we are human, we are from the same planet. Other friends have come and they ask why this place appears on Cuba’s tourist guide.

Luis Trelles: It’s true. Maria’s Patio it still on some old tourist guides, where it’s labeled as the best place in Havana to listen to rock music. But it’s not, of course. During my visit to the old center, I saw middle-aged men that slept under the sun while they listened to rumba. But I didn’t see any soviet guitars, no X-ray drum sets, and most certainly no frikis. Where are they?

It’s Saturday night and hundreds of youngsters fill the Maxim Rock theatre. Some look younger than 15 years old and they fight for their place among the older frikis, who are all in front of the stage’s speakers, banging their heads to the rhythm of the music.

Dionisio Arce: You now have a room with air conditioning, with a roof, lights, great sound, with a bar to drink rum, soda or anything you want, and all that.

Luis Trelles: The Maxim was founded in 2008. It’s the official rock and metal venue in Havana. It certainly didn’t fall out of the sky. The bands had to make a lot of noise to get it, but the opening of the theater marked a huge transformation.

Dionisio Arce: We don’t ask you ID, you can have long hair and tattoos. We’ve had a 180-degree change for good because from Maria’s Patio to the Maxim Rock theatre there is a huge improvement.

Luis Trelles: The Maxim is not only a concert hall; it is the also the headquarters for the Cuban Rock Agency, a government office that represents professional bands in Havana. And that means that the government now pays the bands that are part of the agency.

María didn’t stay behind either. Her self-imposed exile ended earlier in the year, when she became the new director for the government agency. The challenges she faces in the immediate future are clear: now that the government supports the bands with salaries and a theater, there’s pressure for the entire project to turn a profit. Everyone, even the frikis, have to be profitable. It’s the way of the new Cuban socialism.

Back on stage at The Maxim, Dionisio closes the night’s concert with his band, Zeus. But before finishing, he pauses.

Dionisio Arce: We are directly from 37 between Paseo and Dos, from El Patio de María.

Luis Trelles: It’s an important reminder: the frikis come from Maria’s Patio, where there were no lights, no pressure to make money, no modern stages. And where the only thing that mattered was the music.

Daniel Alarcón: Luis Trelles is a producer at Radio Ambulante. He lives in San Juan, Puerto Rico. On our website, you can see a photo and video gallery of the black tide and the longhaired Havana frikis.

This story was edited by Camila Segura and I, Daniel Alarcón, and mixed by our intern Andrés Azpiri. The Radio Ambulante team includes Silvia Viñas, Fe Martínez, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Barbara Sawhill, and Caro Rolando. Our interns are Emiliano Rodríguez and Luis Fernando Vargas. Carolina Guerrero is our CEO. For this story, we used Universidad de Puerto Rico en Río Piedras’s radio studios.

Know more about Radio Ambulante and this story on our website radioambulante.org. Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thank you for listening.