24 Chickens Per Minute | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

♥ We live in difficult times. We are a non-profit media, and our permanence depends on listeners like you. If you value our work, join Deambulantes, our membership. Help us elevate Latino voices and tell the story of our communities. Your contribution is directly invested in our journalistic work and makes all the difference.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

The following English translation was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence.

[Daniel Alarcón]: This episode contains disturbing scenes. Listener discretion is advised.

This is Radio Ambulante, I’m Daniel Alarcón.

[Daniel]: Many of us—and I include myself – don’t know or prefer not to know—where the food we eat comes from. Who makes it and how.

[Rosario]: Because humanly speaking, it’s really hard, very hard to work there.

[Daniel]: This is Rosario, she asked us to call her that in this story. She’s Mexican and in 1995 she came to the United States, more specifically to Springdale, a small city in northwest Arkansas. It’s an area where there are many chicken processing plants, from various companies, but we’re going to focus on one of them. In 2009 Rosario started working at one of their plants.

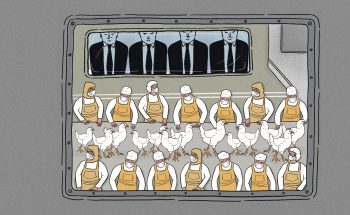

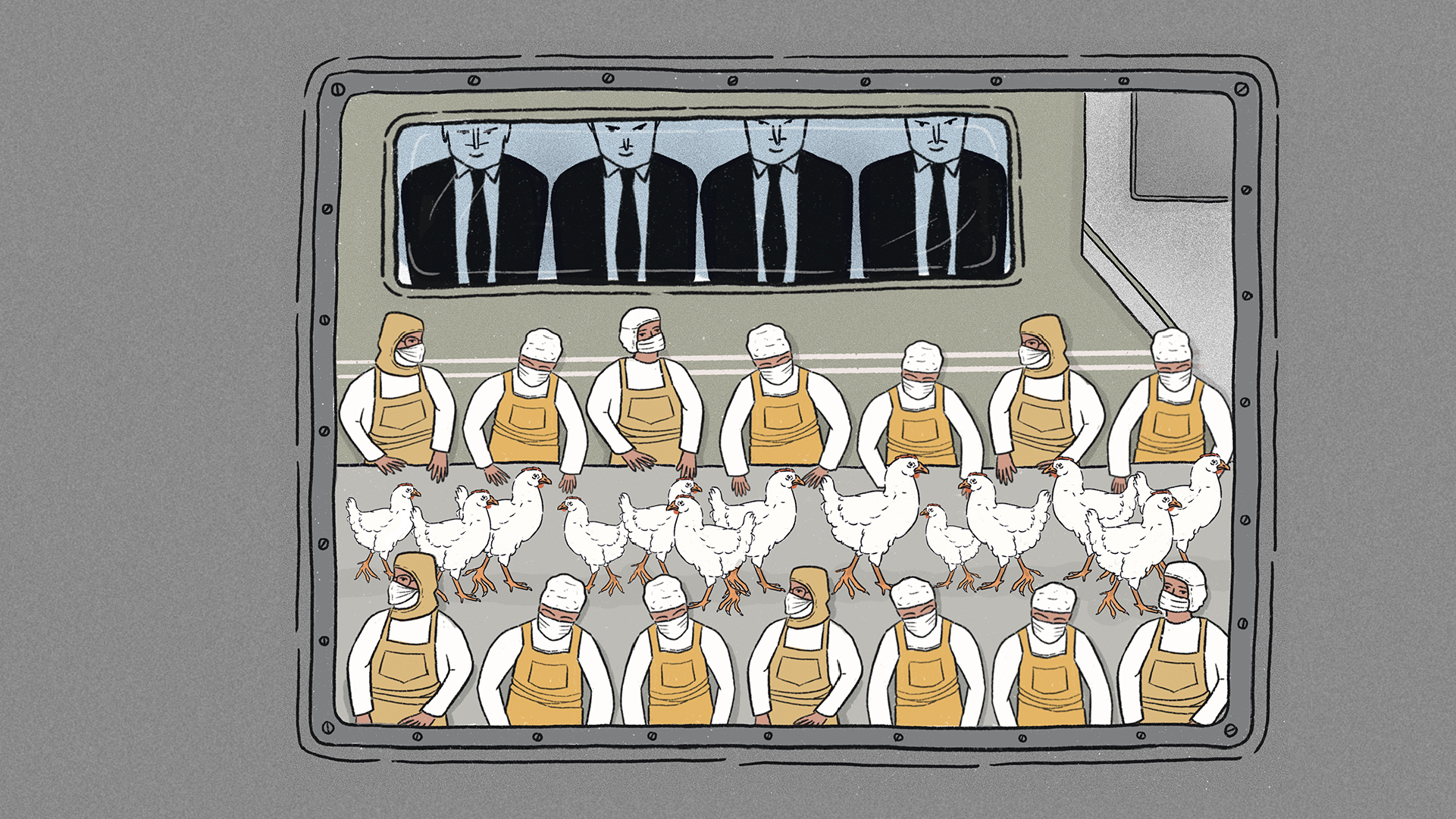

For 8 hours she would stand in front of a conveyor belt, she called it the line, and dead chickens would pass by on it. With one hand, she gripped a very sharp knife and with the other, covered by a metal glove, she took the chickens and cut off their wings.

[Rosario]: You have to be as fast as you can because the line goes too fast. If the line beats you and the wings go by, you have problems with the leaders, with the supervisors. So people are scared, so they have to be in constant movement all day.

[Daniel]: Rosario could debone about 4 chickens per minute. 240 per hour. 1920 per shift. Currently, at the plant they slaughter almost 200 thousand chickens a day. More than a million a week. Deboning is dangerous work. Because of the repetition, because of the speed of the line, because of the knives, because of the chemicals used to disinfect the chickens and clean the plant. And because of the machines: saws to cut the chickens, blades to mix the meat… And because of the floor: slippery from water and grease. And well, also because of the temperature: about 10 degrees Celsius to prevent the chickens from rotting.

[Rosario]: Practically your mind becomes like a constant rhythm already.

[Daniel]: Like a machine that never stops.

[Rosario]: That’s how our thinking is, our system, our organism, our hands, our everything.

[Daniel]: It was a sensation that accompanied her every day back home.

[Rosario]: I was asleep and I felt like my head was there, my thoughts were in the rhythm of being in constant production working. Your mind doesn’t rest. It goes back to being like a machine. It’s very hard to endure.

[Daniel]: But she endured it. Because the job also had its benefits: health insurance, paid vacation, retirement plan. So yes, maybe there was monotony, danger, fatigue and pain. But those risks didn’t weigh as much as her dreams.

[Rosario]: Well my dream was to get ahead, to start a business… And more than anything, to help my parents in Mexico because of the great need that existed.

[Daniel]: Work, work, work. That was the formula for success.

Until one morning in June 2011.

That day, shortly before 9, one of the plant supervisors poured chlorine into a large container. Something routine: chlorine is used for cleaning. But the supervisor didn’t know that the container had residue of an acid used to disinfect chickens.

The mixture caused a tremendously powerful chemical reaction… Maybe you’ve heard about chlorine gas, which was first used as a chemical weapon in World War I. It closes your throat, burns your lungs, suffocates you. Well… when the supervisor mixed those two substances, an enormous cloud of chlorine gas began to emerge from the container and spread throughout the plant, where about 600 people were starting their workday.

Rosario was in a large warehouse focused on her line, when suddenly she felt something in her body.

[Rosario]: I didn’t know if it was in my chest or throat. It was like something I had inside.

[Daniel]: Then someone shouted that a chemical was spilling. And she ran.

The nearest exit was a small door where many workers started to crowd together. But they didn’t know that the gas was coming precisely from the hallway that was on the other side of the door.

[Rosario]: Practically they threw us to the slaughter, I felt. Nobody warned us over the speakers, nobody told us not to go through that dangerous place that was full of chemicals.

[Daniel]: The workers tried to escape while the gas enveloped them.

[Rosario]: I don’t even know how to describe it. If it was white cloud, if it was hail, if it was rain or if it was smoke. First I covered myself with my sweater. Then I couldn’t cover myself anymore because I felt like I was drowning more. And then I opened my mouth so air could enter, but no air entered, more chemicals entered.

[Daniel]: Rosario crossed to the hallway. She saw a woman stumble, people stepping over her, and a man trying to lift her up.

[Rosario]: I practically saw death close by because I felt very alone because there was nobody to help you.

[Daniel]: She got outside, still struggling to breathe.

From that moment on, Rosario would begin to realize that working and working, no matter how, wasn’t enough to reach the life she dreamed of.

After the break we tell the story.

[Daniel]: We’re back. This episode was produced by journalists Alice Driver and Pablo Argüelles. Pablo continues telling us.

[Pablo Argüelles]: On the day of the chlorine gas accident, Springdale only had four ambulances available, so several public transit buses had to take 173 workers to hospitals in the region. They took Rosario to one that was 20 minutes away.

[Rosario]: Oh, it lasted an eternity for me. I don’t know if it was months or years or I don’t know, but it was something really, really difficult.

[Pablo]: During the trip a woman told her to think about the people for whom it was worth living. Rosario remembered her daughters and that gave her strength, but when she arrived at the hospital, she was almost fainting.

[Rosario]: There was no oxygen left. I remember they told me they were going to put a tube down my throat and from there I didn’t know what happened anymore…

(Archive soundbite)

[Host 40:29 New]: Now let’s turn to one of the hospitals that saw more than 30 Tyson workers today…

[Pablo]: Throughout the day, local media began to cover the news.

[Reporter]: Early Monday morning, the head of this hospital issued a code green. A code green means there has been a community disaster and the hospital needs all hands on deck…

[Pablo]: The hospitals were in code green: a disaster had occurred and they needed all their staff.

Rosario spent a few days in intensive care. Then Tyson told her she had to come back to work. And she couldn’t refuse.

[Rosario]: Because I had a great need to support my family. And I felt that sick, in another place they would want me even less, they would put up with me even less.

[Pablo]: Months passed, she worked, but she didn’t stop feeling weak, she was short of breath. And when she asked for consultations with the plant nurses, they minimized what was happening to her.

[Rosario]: They laughed at you and said that you’re fine and that no, you can’t get sick there. That we’re practically crazy.

[Pablo]: One day, a supervisor told her:

[Rosario]: You’re not sick. You don’t want to do the work. I mean, he didn’t know, as a saying goes, that only the spoon knows what’s in the pot. And so he didn’t know how they felt, what we felt. That, I still can’t forget.

[Pablo]: Besides the trauma from the accident, Rosario started to develop asthma. She was absent from work to go to the doctor. And so she fell into a vicious circle of growing medical expenses and lost work hours, unpaid. Increasingly desperate, she started looking for help. And that’s how she reached her:

[Magaly Licolli]: Yes there are many things that we really have to change in the mentality of immigrants, because yes we understand that yes they come to work, they come for a better life, but in that working and in that better life yes it’s required to know rights to be more prepared, right?

[Pablo]: Magaly Licolli who, at that time, was director of a community workers’ center and was very aware that Rosario’s story wasn’t unique. For several years, Magaly worked at a community clinic in the area. It was bureaucratic work, helping workers from poultry companies navigate the American health system.

[Magaly]: And there well they started to talk, right? About “well no, I don’t work anymore, I can’t work. This accident happened to me…”

[Pablo]: She quickly understood that the situation was serious. People told her all kinds of things…

[Magaly]: Many say they sometimes can’t even grab their keys, right? Or things fall from their hands, they don’t have enough strength. Severe back problems. People who cut themselves or rather amputated their fingers, right? Workers, um, who told me “it’s that Magaly I have holes in my lungs” and I was like “how is it that you have holes in your lungs and you don’t have health insurance and you don’t have treatment and nothing…” I mean!

[Pablo]: And although “holes in the lungs” is an exaggeration, accidents like the gas one and being constantly exposed to chemicals like chlorine could cause damage to the respiratory system.

[Magaly]: I mean, I couldn’t believe that in processing food, workers were exposed to ending up like this. There are so many cases that you start to understand that it’s a systemic problem. It’s a problem of how industries treat these workers.

[Pablo]: But the health impact was only one of the barriers they encountered every day. Language was another.

[Magaly]: They sign contracts they don’t understand. They don’t understand the company policies. That’s very, very common. And the worst of all is that when they fire them or they finish working because they can’t anymore because of those injuries, there’s no worker compensation, right? They’re basically left helpless without health insurance, without work.

[Pablo]: It was a cumulative effect. The more Magaly talked with people who came through the clinic, the more and more indignant she became. Filling out forms at a desk fell short.

[Magaly]: I felt that the work I was doing wasn’t something that filled my heart.

[Pablo]: She had to help workers in another way. So she gave her life a turn: she joined a union.

[Magaly]: So I started traveling… to Chicago, to Kansas… And the truth is that I loved it because it was this idea of creating power in people, right? Of everyone united creating this force, I mean, awakening and fighting and saying enough, right?

[Pablo]: Then, in 2016, she became director of the Workers’ Center we already mentioned. That’s where Rosario arrived. A relative told her about that place.

[Rosario]: They sent me there because I didn’t know there was help for workers.

[Pablo]: The thing is the Center helped workers obtain compensation from companies. Rosario managed to get Tyson to help her with some medications but it definitely wasn’t enough. Even so, she liked the Center. There she could find information about how to improve her working conditions.

[Rosario]: And that’s why I kept going constantly to learn my rights.

[Pablo]: And the thing is, according to Rosario, in the plants that information isn’t shared. Rather, she told us that supervisors blame workers for everything.

[Rosario]: If they fall, it’s their fault. If they cut themselves, it’s their fault. If there are no gloves, no appropriate supplies, it’s their fault. They’re practically giving them psychological therapy.

[Pablo]: But demonstrating that this didn’t have to be this way was work that the Center did against the current. First because the poultry companies had enormous influence in Arkansas. There they donated to universities, hospitals, food banks, sports centers… Not counting their lobbying in the political world. So, confronting them wasn’t well regarded.

[Magaly]: It’s like all the time people were telling you that’s not done, that’s wrong, right? We have to be proud that these companies are so powerful nationally and that they’re providing work for people. Many times immigrants also commented to me: “It’s that you don’t bite the hand that feeds you.”

[Rosario]: Everyone is afraid of that. Of losing their job, of the retaliation they take against each worker.

[Pablo]: But there was another problem. Workers didn’t trust Magaly much because she wasn’t one of them. And the Workers’ Center only worked if everyone got involved. They needed inspiration, to leave the plants and Arkansas, to go to places where other workers had already mobilized.

[Magaly]: So, well, we went to Immokalee… And it was the trip that changed the entire destiny of our struggle.

[Pablo]: And Rosario was also on that trip.

[Rosario]: For me, it was something really beautiful, that experience of learning. And I found that, well as they told me, that’s how it was…

[Daniel]: After the break, Magaly and Rosario travel to Immokalee, a small town in Florida.

We’ll be right back.

[Daniel]: We’re back on Radio Ambulante. Pablo continues telling us.

[Pablo]: So, in 2018 Magaly, Rosario and other members of the Workers’ Center traveled to Florida to meet the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. They were a group of farmworkers, mostly Latino, and until a few years before they had worked under conditions of modern slavery: the landowners stole their wages, threatened them with death, prohibited them from drinking water during work… At first the farmworkers tried to negotiate with those owners but they wouldn’t listen to them. So they had an idea.

[Magaly]: They started analyzing that, well, the tomato we pick here in Immokalee, where does it end up? And they started to understand that that tomato ends up in the hands of corporations like Taco Bell.

[Pablo]: They thought Taco Bell would be scandalized to learn about the working conditions in the field.

[Magaly]: And obviously Taco Bell well didn’t care about that, right? It’s like “well what’s it to me?” Well, not to you but to your consumers, yes.

[Pablo]: The Coalition decided to promote a boycott of the company. They traveled throughout the United States informing about what was happening. They got support from more than 30 Christian churches, about 45 million people. And they also involved students from very important universities like UCLA or Notre Dame.

[Magaly]: That’s when you involve consumers to put pressure on these corporations so they adopt codes.

[Pablo]: In 2005 the Coalition got Taco Bell to sign a contract in which they committed to pay one cent more for each pound of tomatoes harvested. It sounds like little, but with that the farmworkers’ wages were doubled. In the following years other companies like McDonald’s, Whole Foods and Wal-Mart joined the agreement that today guarantees farmworkers the right to complain about working conditions without fear of retaliation, to have copies of their contracts in their language, to be able to rest every two hours or take shelter in the shade…

[Pablo]: This is the Fair Food Program. It has been recognized by the UN and adapted by other industries in the United Kingdom, Chile and South Africa. Its logic is simple: by guaranteeing workers’ dignity, companies also win because they don’t lose consumers.

[Magaly]: So these are rights that are reinforced by the market. Which makes it much more powerful because, whether or not laws exist in the state or they change them or remove them, that’s not going to harm this type of contract. When we learned that, the workers said “well, what are we doing? Let’s do it too.”

[Pablo]: They were going to involve consumers and pressure the poultry companies to improve working conditions.

But, back in Arkansas, the idea wasn’t well received by the Workers’ Center board of directors. They thought so much activism could get them into legal trouble with the companies. For Magaly it was the same signal she had received before: nobody dared to raise their voice against the poultry companies. They had to build something new with what they learned in Immokalee.

[Rosario]: I wished there was an organization so we could continue fighting for our rights. And united well the voice is stronger.

[Pablo]: So Rosario, Magaly and 14 other workers founded in October 2019 an organization called Venceremos. And without knowing it they became a vital space for what was coming: the pandemic. Because while most of the world stopped, businessmen and politicians asked food industry workers not to be absent from the plants.

[Mike Pence]: Just understand that you are vital.

[Pablo]: This is then-Vice President Mike Pence in April 2020.

[M. Pence]: You are giving a great service to the people of the United States of America. And we need you to continue as a part of what we call our critical infrastructure to show up. Uh, and do your job.

[Pablo]: Understand that you are vital, he told them. You’re giving a great service to the United States. We need you to keep working. But for Rosario, returning to the plant was impossible.

[Rosario]: Because it was too much damage for me, for my lungs that every day, well I felt more deteriorated.

[Pablo]: The asthma she developed from the chlorine gas accident and that had her so weakened, made her very vulnerable to infection. So a doctor gave her medical leave and she stopped working for Tyson in March 2020.

[Rosario]: Well thanks to that, I’m still telling the story because if I had stayed there during the pandemic, maybe I wouldn’t be telling it like other colleagues.

[Pablo]: Because thousands of workers had no other choice but to continue.

[José]: To our own faces they told us that any person who wanted to stop working and stay home was fine, but that they weren’t going to pay those people a single cent. So, what were people going to do?

[Pablo]: We’ll call him José, that’s not his real name, he’s Mexican. In 2010 he started working at the same plant as Rosario. Then he moved to another one in the city of Rogers, very close to Springdale. And with the pandemic, he started seeing signs there that said something like: “You, the workers, are essential.” They were messages that were complemented by those from their supervisors.

[José]: That there wasn’t enough meat to feed people and that’s why they were producing as much as they could, to feed the country.

[Pablo]: And although a Congressional investigation later showed that there was never a meat shortage in the United States, that excuse ruled in the plants during the first months of the pandemic. And so, even when José started noticing that workers were absent… the speed of the line continued.

[José]: And there were complaints from people about why they were making us work even more than we worked before. Because they even made us work Saturdays and sometimes even Sundays.

[Pablo]: From those months José remembers the widespread fear.

[José]: Nobody talked like before. Everyone was afraid to get close to another person. Even if they heard someone sneeze or cough nobody got close to them for fear they were infected.

[Pablo]: And the thing is, according to José, at his plant supervisors minimized the risks of the virus.

[José]: All the time they told us that the virus was outside, that the virus wasn’t inside there.

[Pablo]: He felt that his bosses weren’t being honest. It was actually a feeling he’d had for a long time. Since he heard about the chlorine gas accident. According to José, Tyson assured them that an accident like that wouldn’t happen again and that they had fired the responsible supervisor. But for José, those were empty words.

[José]: I never again had confidence in what the company told me when they hired me. They use a phrase that says that their employees’ safety is first. And there I realized it’s a lie because they didn’t take care of workers like they said.

[Pablo]: The frustration with working conditions during the pandemic convinced him to join forces with other workers. He joined the group we already mentioned and that by then was making more and more noise in their favor: Venceremos. The thing is from the beginning, Magaly started receiving messages from workers at various poultry plants. They were all variations of the same complaints: our bosses aren’t informing us about the virus, we’re working elbow to elbow, we’re scared.

[Magaly]: Not much was known about Covid. It was known that many were dying because of lung problems. Many already had respiratory problems. So yes it was a historic moment in the sense that people had that urgency, right? I mean my life or what, right?

[Pablo]: And that urgency drove Venceremos.

In mid-March 2020 workers started signing petitions demanding that poultry companies like George’s, Simmons and Tyson increase wages and pay during periods of illness.

[José]: I was even collecting signatures at work, hiding so they wouldn’t see me.

[Pablo]: In April, Magaly went to a Tyson plant in Springdale to deliver one of those petitions to the managers, signed by about 170 workers. She did it on Facebook Live. That day it was raining and she carried an umbrella and two masks.

[Magaly] (FB LIVE): We are here in the name of all the workers who couldn’t be here, who are inside there…

[Pablo]: The news came out in the media.

(Archive soundbite)

[FoxNews]: In Springdale more than 170 employees demand change at Tyson food plants during the COVID 19 pandemic…

[Magaly]: And from there we grabbed on, right? We said now we have all the attention of all the national media and we don’t stop.

[Protester]: Tyson, the people have some questions! Are you going to protect your image and your money, or are you going to protect your workers?

[Pablo]: This is a recording of a protest they held on May 29, 2020 in front of a Tyson plant in Springdale. About 20 people went. They did these types of demonstrations once or twice a month, outside poultry plants in the region. Workers, students, religious leaders went.

[Protester]: And we will not be silenced! We are here to fight for justice! Wooooo!

[Pablo]: And well, the pressure… more or less worked.

Tyson began giving more protective equipment to its employees and installing separators between workers along the lines, although, according to reports, not in all of them.

But even so, the chances of getting infected inside a meat plant were much higher than in other industries for the mere fact that social distancing couldn’t or wouldn’t be done on production lines. For example, between April 2020 and 2021, Tyson was the Arkansas company with the most Covid-19 cases, about 2,800, even though it wasn’t the company with the most employees in the state.

According to Tyson, between the beginning of the pandemic and February 2021, 151 workers from their plants died throughout the United States because of the virus. According to the company’s figures, one worker died at José’s plant. And at the plant where Rosario had worked, four died.

In December 2020, Venceremos organized a vigil in honor of the dead workers.

[Magaly]: They are missed, at work, in their families. It’s not normal that they died the way they died…

[Pablo]: That night, Magaly, the workers and family members present read some of the names of the dead.

[Magaly]: Martín Barroso!

[People]: Present!

[Magaly]: Raúl Camacho!

[People]: Present!

[Daniel]: The pandemic was exposing more than ever the fragility of working conditions at poultry companies. And workers needed something more, something big that said they were there. After the break we tell you.

[Daniel]: We’re back. Here’s Pablo.

[Pablo]: Since late 2020 Magaly and a dozen members of the organization were considering a class action lawsuit against Tyson. Magaly contacted a law firm specialized in suing large companies. Then she and an investigator started looking for families of former workers who had died in Arkansas, people who would be willing to put their name on the lawsuit.

[Magaly]: We went from town to town basically knocking on doors and saying, “look, well we’re doing this”…

[Pablo]: They spent about two years building the case. They collected testimonies about everything that happened to workers and their families, people who had been suffering damages for a long time. And in March 2023, they filed the lawsuit. Thirty-four workers, former workers and family members accused Tyson of extreme emotional damages. Both Rosario and José included their names.

[José]: And well yes, people were really excited because the evidence they had, well there was a lot and it was very valuable evidence.

[Pablo]: But a few months later an Arkansas judge dismissed the lawsuit. The reasoning was short, written in dry, legal language: first, it said the court didn’t handle workplace injury cases; also, it followed the argument of an executive order that Arkansas’s governor signed in June 2020, during the pandemic, which protected companies from lawsuits for damages caused by Covid-19. The lawyers appealed the decision, but unsuccessfully.

[José]: So, when we found out about the decision, well yes, it was something that disappoints you completely and that if with all that evidence we gave nothing could be done then, in what way can something be done?

[Magaly]: I got really angry because obviously it wasn’t just the workers’ hope but it was the workers’ trust they had built, right?, with Venceremos. Because the thing is trust can take a lot of time to build, but it can be lost overnight.

[Pablo]: Rosario didn’t want to talk about the lawsuit with us. We don’t know if the result disappointed her or if she lost trust in Venceremos. The only thing she told us was that, although raising your voice against such powerful companies is very scary, it’s also worth it:

[Rosario]: For life. Because if we raise our voice, if we unite among several, they can hear us. But if we’re alone, they don’t hear us.

[Pablo]: But the paradox is that, currently, Rosario is no longer very involved with Venceremos. And José doesn’t participate frequently. It’s because of a lack of time and energy and also motivation. Because they no longer work at the poultry plants. They’ve already fought their fight, so exhausting, with results, as we’ve seen, so unequal. Maybe now they hope other people will relieve them.

[Magaly]: Um, well, first of all well since many don’t know each other, many know each other, but let’s introduce ourselves, our name, where we work…

[Pablo]: In January 2025 I connected by Zoom to a general assembly of Venceremos. In a small room in Springdale were Magaly and about ten workers from different poultry companies. At first they didn’t look very animated. But slowly they started talking about their concerns in the plants, from bird flu to robotization. And then they moved to the main reason for the meeting.

[Magaly]: I want to hear from you what’s happening. How have you felt this week now that Trump is back? How have you seen the community?

[Pablo]: It was the first week of Donald Trump in the presidency and around the country massive raids were beginning to deport migrants. About this, one of the workers said:

[Woman]: I think we’re all going to be affected in some way and because of the situations that are happening, because of the people they’re deporting, because of those separated families.

[Pablo]: And the thing is, although it was understood that the workers present at the assembly did have papers, that didn’t prevent family members and friends from being at risk.

Later a man mentioned how the atmosphere of fear could disunite them as workers. Because in the plants there are workers with residency and citizenship, but also with temporary work visas. Even without papers.

[Man]: I work with one who doesn’t have papers and we do the same work. You judge: am I more than the one who doesn’t have papers or is he more than me if we do the same work and they pay us the same? We’re equal. And if we separate ourselves it’s better for them. Why? Because we can’t strike, we can’t do anything separately.

[Pablo]: At one point in the meeting, Magaly talked about the surveillance committees she was starting to form with Venceremos allies. Religious leaders, neighbors, students: people willing to record with their cell phones and help in case of raids or arrests.

[Magaly]: Although the laws are against sanctuaries, we can create a sanctuary within our own community and support each other, right?

[Pablo]: But some workers didn’t look very convinced. With so much fear, who was going to dare defend migrants? There was pessimism in the air. But also indignation. What had changed so that during the pandemic they called them essential and now they didn’t?

[Magaly]: What happened with that?

[Man]: Not anymore, they send immigration after you.

[Pablo]: “Not anymore, they send immigration after you,” one said. Then a woman intervened.

[Woman]: I don’t need you anymore, I throw you in the trash.

[Pablo]: I don’t need you anymore, I throw you in the trash. As if they were disposable. The woman continued, raising her voice more and more, as if the companies and consumers and really all of the United States were there, listening to her. She didn’t want them to applaud her or call her a hero.

[Woman]: I’m not saying that we… “oh how good”… No, no…

[Pablo]: What she was asking for was something simpler.

[Woman]: We are human beings. Simply that they recognize our value and like them, even though it hurts us and even though it hurts them, they eat from our hands.

[Pablo]: It’s something to remember the next time we shop at the market.

In March 2025 we contacted a Tyson Foods representative by email. We wanted to ask about safety measures in the plants and workers’ working conditions. We received no response, at the closing of this story.

Pablo Argüelles is a Mexican journalist. He lives in Madrid. Alice Driver lives in Phoenix, Arizona and is also a journalist. This story was edited by Camila Segura and Luis Fernando Vargas. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Andrés Aspiri with music by Remy Lozano.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Adriana Bernal, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, David Trujillo and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, it’s produced and mixed in Hindenburg PRO.

If you liked this episode and want us to keep doing independent journalism about Latin America, support us through Deambulantes, our membership program. Visit radioambulante.org/donar and help us continue narrating the region.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.