Berta and the River – Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón]: A warning before we start: this episode contains difficult scenes that aren’t suitable for children. Discretion is advised.

Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

It’s March of 2016 and we’re in Honduras.

(NEWSCAST SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: There’s commotion and protests in Honduras after the assassination of 45-year-old Berta Cáceres

[Journalist 2]: In Honduras: Berta Cáceres, a recognized indigenous leader and environmentalist, was murdered today by unknown persons.

[Daniel]: Berta was about to turn 45 and lived in La Esperanza, in western Honduras. She and her family are Lenca descendants, the largest group of indigenous people in the country.

From an early age, Berta began her struggle to improve the living conditions of the people in her region. She also defended the Lenca ancestral lands and sought to protect the environment from private interests and governments that wanted to set up mining, logging or hydroelectric projects.

(NEWSCAST SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: Cáceres was murdered Thursday at her home in the western city of La Esperanza, apparently by two men carrying firearms.

[Journalist 2]: The authorities believe those responsible are three heavily armed men, and for now they are carrying out the investigation into the motives for the homicide.

[Daniel]: Her struggles led her to denounce crimes in the Lenca communities perpetrated by powerful groups. There were also threats against her life for many years. But so many alerts, calls, and warnings were of no use.

The news of Berta’s assassination caused commotion in Honduras and abroad. Even President Juan Orlando Hernández, whom Berta had strongly opposed, spoke out publicly.

(NEWSCAST SOUNDBITE)

[Juan Orlando Hernández]: Authorities at the police investigation administration are fully deployed in the area and also in other places, to find those responsible and bring them to justice.

[Daniel]: At first, the official investigation spoke of a robbery or even a crime of passion, some kind of revenge for jealousy, an affair with an ex-partner. But as soon as they heard about the murder, neither her family, her friends, nor even her colleagues in the struggle, doubted where the attack had come from and it had nothing to do with that conjecture.

(NEWSCAST SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: Today, with a moving farewell, they said goodbye to the indigenous leader who was assassinated, while her family demands justice and punishment for the authors of the crime.

[Daniel]: As far as they were concerned, there was a clear motivation, and it even had a name.

Today at Radio Ambulante, we return to a case that continues to be controversial in Honduras. A case that remains open even today, five years later.

Chiara Eisner, David Trujillo, and Victoria Estrada reconstructed this story.

Victoria continues.

[Victoria Estrada]: We’ll come back to the night of Berta Cáceres’s murder later on, but before we do that, we have to understand how she came to be such an uncomfortable figure for certain people and interests.

She was born in 1971 in La Esperanza, very close to the border with El Salvador. She was the youngest of twelve children, and she became an activist from her teen years. This is her second daughter, Berta Zúniga.

[Berta Zúniga]: My mom was a social fighter. She began from a very young age to organize in student movements.

[Victoria]: Movements that demanded better educational conditions or that opposed compulsory military service for young people. But her greatest interest was the Lenca people. Although it is the most numerous indigenous ethnic group in Honduras, and although the national currency, the lempira, bears the name of a legendary Lenca chief, it is a population that has always suffered from the abandonment by the State.

Berta was concerned about the racism, the machismo and segregation of which the Lenca people continue to be victims. She fought, among other things, against the dispossession of their lands by different governments or private companies, and demanded that the State guarantee their fundamental rights.

This is Berta speaking to one of those communities in 2013.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Berta Cáceres]: My companions, colonialism has not ended. That is why this fight is so tough for the indigenous people, and there is a State apparatus at the service of that. But we also have power, companions, and that is why we continue to exist.

[Berta]: She was greatly inspired by group struggles and also by seeing the resistance and dignity of the Lenca people. They kind of filled her with pride.

[Victoria]: In 1990 she gave birth to Berta Zúniga, her second daughter. Then two more children would follow. In 1993, Berta Cáceres, who at the time was twenty-two years old, together with ten other people, founded COPINH, the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras. They created it to better organize the collective struggle for the political, social, economic and cultural rights of different indigenous peoples, particularly the Lenca community.

Berta’s ex-husband, Salvador Zúniga, was also a co-founder of COPINH. Berta, the daughter, accompanied them many times on their trips to visit the Lenca communities in their area.

[Berta]: Well, that meant that I also grew up, seeing, let’s call it the marginalization, in the life of a large part of the boys and girls and the communities in general.

[Victoria]: Sometimes she also accompanied them to celebrations or ceremonies. On one occasion, when she was about six years old, her mother took her to a compostura, which is perhaps the most important of all ceremonies for the Lenca people. As part of that ritual, they distribute corn chicha in a cup, or huacalito, as she calls it, and everyone takes a sip.

[Berta]: So when they handed the huacalito to me, I kept staring like this because I knew that I was a child and this was an alcoholic drink. And then she said, “Drink it.”

[Victoria]: She obeyed and took a small sip.

[Berta]: And . . . and I thought it was disgusting (laughs). So I started screwing up my face.

[Victoria]: Her mom scolded her.

[Berta]: She told me . . . to stop making faces, that it was a . . . a serious thing and that this was part of the spirituality of the Lenca people, so that I could not make faces.

[Victoria]: Of course, the Lenca identity shaped the struggle of her parents, of her community, of COPINH. But at the time, Berta the daughter was a child and none of this made much sense.

[Berta]: I grew up surrounded by a lot of meetings that I found really boring, but hey, it was a like a part of the process. I didn’t understand any of that.

[Victoria]: Nothing about the struggles they had or the way they worked. But the truth was that COPINH was starting to have a leading role even at a national level. They succeeded, through peaceful pressure, in getting the government to build roads, schools, health centers, projects to take drinking water and electricity to indigenous communities. They also took on private industries and shut down dozens of sawmills that were logging indiscriminately in protected areas.

And perhaps the most important victory during those first years was in 1995, getting the Honduran State to commit to honoring a very important international agreement. It’s called Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. Several countries signed it, and the objective is to recognize the rights of indigenous communities over their lands and natural resources. But also—and this is key to the story—it forces the government to first consult these peoples regarding any plan, law, or project that affects them. In short, this agreement was the legal and political weapon they would have in their fight to defend themselves against anyone who tried to bypass them.

Berta was always there, often leading the struggles.

[Berta]: She was a woman who was not afraid to name or challenge any oppressor of any kind, in any place. She started leading in a pretty important way, even confronting several male chauvinist leaders within the organization.

[Victoria]: And over time she became the general coordinator of COPINH. Although the work was paying off, it was clear to Berta the daughter that what her parents were doing was uncomfortable, even within her own family.

[Berta]: Especially my uncles, who were always opposed. Why bother fighting for those Indians, they said, they were an ungrateful bunch, so why go risking their own lives.

[Victoria]: Yes, comments like those, even though they were also of Lenca ancestry. But above all, what those uncles criticized most was the fact that since Berta and her husband had to travel so much, her children lived at their grandmother’s house.

[Berta]: They told her that she had left the . . . her daughters and son behind. That we were freeloaders because in the end, my grandmother had to cover a lot of . . . of expenses because COPINH didn’t provide any fixed income. I mean, it was . . . the economic situation was very complicated.

[Victoria]: So much so, that in the late nineties Berta Cáceres had to go to work in the United States for a while. That way, she could get some money to support them. At that time, the economic situation all over Honduras was getting complicated, and her departure was part of a wave of people who left the country in search of opportunities.

It was complicated, and although arguments in the family were constant and uncomfortable, Berta Cáceres had a very strong character, so they preferred not to argue with her much. In addition, her mother, that is, Berta the daughter’s grandmother, supported the struggle and endorsed having her grandchildren there.

But the problems went far beyond family arguments. COPINH’s fight involved risks, even for the children.

[Berta]: It felt, let’s say, like a persecution, a climate of hostility. And well, even as a child I also learned how to take certain measures because of the work they did.

[Victoria]: Neither she nor her siblings could go out alone. There was always someone they trusted who would take them to school and pick them up at the door, even when they were teenagers.

It was not a quiet life because they really had to experience dangerous moments. Like the time the older sister realized there was a very suspicious man who seemed to be spying on them. He was standing in front of the house where they lived at the time, watching, and did not move from there. They decided to call their parents, who were working elsewhere, and ask for their help.

[Berta]: They sent the police and it turns out the man had a gun, and although he was a man, let’s say, of modest means, it looked like he had been paid to do something.

[Victoria]: An attack. On another occasion, a man with a knife tried to get into the house. The woman who looked after them closed the door just as the man managed to get his arm in and was waving it in all directions.

[Berta]: And he managed to cut her cheek, and he cut a part of her arm. But we had two dogs and one of them got loose and went at the man. That’s how she was able to close the door.

[Victoria]: And the man with the knife left. Fortunately, these attacks or attempts didn’t go any further, but it was very hard to get used to living that way, even though they had been living in that environment forever. Not only did they have to put up with the annoying comments from relatives and outsiders who criticized what their parents did—they also had to deal with the anxiety of knowing that something could happen at any moment, and with the discomfort of having to move constantly for financial and security reasons.

[Berta]: I said to them once, “Oh, why can’t you be normal parents? Darn it, mom, you are a teacher, and so is dad. You should devote yourselves to being teachers.” And things like that; I complained to them that I wanted to have a normal life, because I didn’t even know what that was like—a stable life. I wanted to spend more time with them. . . .

[Victoria]: Sometimes she would cry when her mother went to work. But she always answered her . . .

[Berta]: Sometimes very sweetly, but sometimes very harshly as well: “Oh, darling, you don’t understand yet, do you? What we’re doing—the importance of this fight.”

She would say that . . . it was a historical moment and it was important to give visibility to the struggles of the Lenca people. And that . . . well, that at some point all those sacrifices that we made would pay off as satisfaction, seeing victories, seeing results, seeing processes.

[Victoria]: And so, perhaps later on they could live in peace and quietly. Berta the daughter believed her. She couldn’t do otherwise. Her mother promised her a better future and she trusted that. Besides, she always showed them that she enjoyed her work, and that what she did was worth it.

[Berta]: She was a very cheerful person too, who always laughed and constantly made jokes. So it was obvious that she enjoyed her work a lot and that she didn’t do it like . . . like oh, like a martyr, or like carrying . . . no.

[Victoria]: As Berta the daughter grew, she understood the situation more and more, and accepted her parents’ decision to devote themselves to that struggle. Over time, she became more involved in it, and in college she studied education and majored in humanities. She also began to collaborate with COPINH.

[Berta]: I was part of the COPINH communication teams. So I would record, make videos, interviews. Well, I gave my support in everything she told me to, right? As part of the operational teams.

[Victoria]: On June 28, 2009, she experienced up close one of the most important moments in the recent history of Honduras. President Manuel Zelaya was removed from office. He had been arrested and expelled from the country by the armed forces. This unleashed a very strong political crisis, and COPINH opposed the coup.

Berta daughter accompanied her mother to the protests in Tegucigalpa, the capital.

[Berta]: I was also very excited to be a part of . . . of that. That was the first time I experienced repression, I swallowed tear gas for the first time, and I was right there with my mom.

[Victoria]: And when her mother realized the situation was getting complicated, she told her to get out of the march.

[Berta]: Sometimes she would send me off to a companion’s house in Tegucigalpa. And then I would throw a tantrum and say no, I wanted to be out there, and what about all the things they had taught me, and that they were inconsistent.

[Victoria]: But her mother, who already had more than twenty years of experience in social struggles and knew how to deal with these types of situations, was not going to expose her daughter to danger. She scolded her and ordered her to leave immediately. The daughter, obeyed her—as always.

After that coup, and because of the tense political climate it unleashed, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights requested protection for Berta and other COPINH leaders.

Although the protests were large, they didn’t amount to much. The new government was recognized by several countries, including the United States. In the months that followed, it opened the doors to private companies—national and international—to start setting up hydroelectric and mining projects, even if they were in protected areas. The justification was that, since Honduras didn’t produce enough electricity and had to buy it abroad at very high prices, they needed to build their own energy sources.

In 2010, the Congress of the Republic approved the contracts for the construction and operation of several energy projects. The one that concerns us here is the Agua Zarca hydroelectric plant, run by a company that had just been created: Desarrollos Energéticos S.A. or DESA, as it is known.

The dam would be built on the Gualcarque River that crosses indigenous territories in the western part of the country. It is about four hours from La Esperanza, where Berta lived.

[Berta]: This is a sacred river for the Lenca people. Spiritually important but also in practice, right? In the life of the community, it is also used for many things—for fishing, for water, for the crops.

[Victoria]: When news of the dam’s construction reached Río Blanco, one of the riverside communities, some of the residents there held a demonstration against the project. Remember Convention 169? The one that protects the territories of indigenous communities? Well, they were claiming that right: the government had not asked them if they agreed or not with Agua Zarca. No one sat down to explain to them what the project was all about.

But there was no reply. A few months went by, and then they learned the authorities had already granted the hydroelectric plant an environmental license good for twenty years. All of a sudden, machinery for the construction of access roads and other preliminary works began to arrive.

Berta and COPINH became aware of Río Blanco’s struggle and began to support the people to stop the project.

[Berta]: My mom was truly inspired by the struggle over the Gualcarque River because the people from that area were very brave in their fight, very determined. So she was very moved to see boys, girls, women, old men, old women, all the people, that is, everyone together and the determination to defend the river with their very lives.

[Victoria]: And here we need to clarify something important. Although the government was saying that projects like Agua Zarca are renewable energy projects and that hydroelectric plants have been built in many parts of the world for more than a century, in recent years it has been questioned whether they really are as good as they’re pictured.

Let me explain. It has been proven that the construction of dams is harmful to the environment; it can kill the fish and other animals that depend on these water sources. Dams can also cause flooding or, in the worst of cases, they can cause rivers to dry up.

Of course, the environmental impact of hydroelectric plants depends to a large extent on their size, and some even say that with good planning, small dams can considerably reduce the negative impact.

For this reason, DESA insisted that this would be a small, well-managed project. In addition, they spoke of the benefits for the communities—the creation of thousands of direct and indirect jobs, reduction of poverty and improved education and health in the area.

But the problem was that the project itself was not very clear, and there was always talk of modifications to the work that the residents were never consulted about. They realized, for example, that DESA had requested a new license to expand Agua Zarca’s capacity, add a third turbine to the dam, and produce more electrical power. Soon the Chinese construction company—and remember this name—Sinohydro, one of the largest in the world in construction and engineering, joined the project.

Later, a report was published from one of the institutes in Honduras that protects the environment. This document said that the water to operate these three turbines was not enough to guarantee the wellbeing of the river. The amount that would remain in the channel would be so small that it would evaporate—disappear completely.

To the inhabitants of Río Blanco it was evident that Agua Zarca was not the small, transparent project the authorities had said. This is Berta Cáceres speaking in a documentary that was made about the struggle in Río Blanco.

(DOCUMENTARY SOUNDBITE)

[Berta Cáceres]: And here, we can see back here, right where we are, is where they are planning to raise a curtain measuring more than twenty meters. They said at first that it was twenty meters, but we know that it is much more, and we know it is not just a dam . . . it is not just a curtain. It is a complex of hydroelectric plants that privatize the Gualcarque River and the other rivers further downstream, which are the Canje and the Ulúa Rivers.

[Victoria]: Despite warnings that Agua Zarca would have serious consequences for the environment, the expansion was finally approved in 2013. DESA submitted what were supposedly consultations it had done in the region to comply with that requirement. In addition, they already had a loan of 24 million dollars for the project. That was a green light to move heavy machinery and close access to the river.

This doubled the community’s resistance. On April 1, 2013, the residents of Río Blanco began a demonstration they called Take Over the Oak, that lasted months.

[Berta]: And the people there, well, they threw stones, sticks, put up a mesh to . . . to prevent the machinery from continuing to destroy that . . . that part of the mountain that goes to the river and that was put there to facilitate access for all the company’s machinery.

[Victoria]: Berta went there to motivate people to continue defending the Gualcarque, their lands.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Berta Cáceres]: When you fight against the Agua Zarca project, you are fighting for the survival of the Garífuna people, for the survival of the fishermen in Zacate Grande, for the working women of this country. We are fighting for all the environmental struggles in this country.

[Victoria]: People began going to other areas where constructions were in progress. They tried to speak with representatives of Agua Zarca, sometimes even with executives or local government leaders who visited the project. They wanted to express their disagreement, the illegality of the hydroelectric plant. But they generally ended up ignoring these claims. They seemed not to have the will to listen to what the community was requesting. Their response was to ask law enforcement for help taking control of the area and to forge ahead with Agua Zarca the hard way. This is Berta the daughter again.

[Berta]: The company intensified its attacks. There was a military presence there. I mean, it looked like a military base.

[Victoria]: They even set up police and private security checkpoints at various points on the roads that connect Río Blanco with other towns. People were detained and searched, even if they were just going to the nearest hospital. And the members of COPINH were the most obvious targets.

[Berta]: They already knew when my mom was going to go. They always searched her. And they kept surveillance on her when she came, when she went, everything.

[Victoria]: When her daughter first went to support the protests, they had to take extra measures.

[Berta]: I went in her car and my mom went in another vehicle; and I have the same name she does. She had already asked me to use my second name. I had to pretend I was not her daughter. I mean, it actually did feel like that; you could say a pretty complicated atmosphere.

[Victoria]: But although the danger seemed to be growing, Berta continued meeting with the communities, organizing them, listening to their demands. She also collected reports of threats and encouraged the people to keep going.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Berta Cáceres]: So don’t worry about that, companions. Look, they have threatened to put us in prison a thousand times, they have threatened to kill us, everything . . . don’t pay any attention to that, don’t pay any attention, companions . . . Don’t let them corner you with it, don’t . . . We are not afraid of that.

[Victoria]: In addition, she publicly denounced all kinds of corruption.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Berta Cáceres]: There are actions by DESA and Sinohydro not only to pressure mayors, representatives, high officials like the Minister of the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, but they also offer millionaire bribes to mayors, to representatives . . .

[Victoria]: On July 15, 2013, some three hundred people from the region mobilized again. During the protest, the army fired at the protesters and killed Tomás García, an indigenous leader who was part of COPINH. Tomás’ son, aged seventeen, was also wounded by a bullet, but survived.

On the day of the assassination, Sinohydro, the Chinese company, suspended its activities in Agua Zarca, and a month later the contract with DESA was terminated. Until that moment, the debate on the project seemed to be between two parties that had no intention of giving in, but the death of Tomás García did create a very dark environment around the hydroelectric plant. COPINH now pointed to Agua Zarca as a murderous project. For a company as large as Sinohydro, having a connection with this scandal didn’t look good.

DESA tried to hold Berta and other COPINH members accountable for Tomás’ death and denounced the demonstrations against Agua Zarca as violent. A judge took up the case and prohibited Berta from visiting Río Blanco. She also ordered her preventive detention. However, the arrest warrant was never formalized and the case was closed a few months later due to lack of evidence.

But that did not prevent various powerful sectors from painting Berta and COPINH as a danger to the country’s progress. This is Aline Flores, president of the Honduran Council of Private Business, during a press conference in October, 2013.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Aline Flores]: The groups that are boycotting—or rather, that are invading and above all making us look bad at the international level—are groups led by Mrs. Berta Cáceres. She has protection from the . . . from the Commission on Human Rights and Amnesty. She is protected by international organizations.

[Victoria]: She refers to the request for protection from the The Interamerican Commission on Human Rights, and to the support by other organizations, like Amnesty International, which protects human rights.

But it was hard to cover the sun with one finger. They were not boycotting the project just because. In addition to Tomás, COPINH denounced the murders of other activistas in the area, including a young kid. The level of violence was impossible to deny.

At the same time, construction was halted because of Sinohydro’s departure, and the departure of one of the most important funding organizations a few months ealier. The cost had been high—too high—, but it was a victory.

In April de 2015.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Hostess]: For her outstanding envitonmental achievement, the 2015 Goldman Environmental Prize is awarded to Berta Cáceres. Río Blanco, Honduras.

[Victoria]: She was awrded the Goldman Prize, considered the Nobel prize for the environment, for her work with COPINH at the Gualcarque River and for getting Sinohydro to abandon the project.

Berta saw that prize, not only as a recognition of the struggle, but as an opportunity to speak on the value of the land, the need to take care of natural resources, to respect the rights of indigenous communities. This is the final part of her acceptance speech when she received the prize:

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Berta Cáceres]: I dedicate this prize to all the rebellions, to my mom, to the Lenca people, to Río Blanco, to COPINH, and to the martyrs, women and men, in the defense of the goods of nature. Thank you very much.

[Victoria Estrada]: But of course, the Goldman Prize was also a political tool for her protection. Because DESA had not disappeared; the contracts for the dam were still in force.

Even in those moments of celebration, Berta had this in mind.

[Berta]: I think that’s why she agreed to receive it. Companions of hers encouraged her to accept it with this valuation.

[Victoria]: They said to her,

[Berta]: “Look, Berta, the fight is very complicated right now. This can give visibility to the struggle.” And that’s exactly what happened.

[Victoria]: Her name, the name of COPINH, and the fight for the Gualcarque River were now known outside of Honduras.

But DESA had no plans to drop this multimillionaire plan so easily.

It had already suggested moving Agua Zarca to the other side of the river, to lands that, according to them, did not belong to any indigenous communities and which therefore required no approval or consultation. Furthermore, and to reduce costs, they redesigned the project. It would now be a run-of-the-river dam, meaning that it would not stop the flow of the river entirely. But even so, part of the flow would be diverted to the turbines. New multimillionaire loans were obtained for this.

Three months after the prize, people at Río Blanco realized that construction had begun once more.

The struggle seemed to have no end. Agua Zarca continued to be on the same river, and switching to the other side of the river didn’t mean there would be no impact on the community.

[Berta]: I was very upset, because I said, darn it, we struggle to to live in a peaceful country, we struggle for peace, but not this, no way.

[Victoria]: But if construction wasn’t stopped, neither was Berta. She went from one place to another, she organized marches in different parts of the area, she traveled to Tegucigalpa where she denounced the abuse by DESA, she gave interviews to the media.

[Berta]: She was super-intensely dynamic. If she had to go to Río Blanco at eleven o’clock p.m. because something had happened, she would go at eleven p.m. She would get home in the early morning, she would stop half-way home. I mean, she was intense about it. She would not rest, she would go on night and day, early in the morning. There were communiques, something had to be done—bam, bam. So there were . . . many, many things she did, it was impressive. So yes, I felt a little overwhelmed. It was not . . . it was not easy.

[Victoria]: On one occasion, she asked her mother how she felt. The answer surprised her.

[Berta]: She said, “Look, honey, I’m going to tell you something. But don’t you say this to anybody, I’m telling you alone. I see that this struggle is going to be very hard to win.” She also knew that there was a great deal, a very great deal, of corruption; they are putting a lot of money into it, they are trying to buy the leadership.

[Victoria]: But Berta was obstinate. In public she continued to stay firm, motivating the struggle against the project. After all, that was her job and the role she had to play in the organization. And well, she could handle all the pressure. What she could not handle was the idea that they would take it out on her family.

[Berta]: Because she was much more afraid of something happening to us than to her. I think that is why she pushed somewhat for several of us to go to school outside the country. We got scholarships or we went to school with the solidarity and support of other companions in other places.

[Victoria]: At that time, anything could happen to Berta, including that Berta the daughter could be mistaken for her mother and she could be hurt. In 2015, they found out that they were being investigated by State intelligence.

[Berta]: My mom got very scared, I had to go into hiding for about a week, at the house of a companion away from here, from La Esperanza. And I was very tired, especially because I had been kept locked in and I said, no, I’m leaving.

[Victoria]: And shortly afterwards, she received a grant to pursue a master’s degree in Latin American Studies in Mexico.

[Berta]: She said, “No, Mexico is as dangerous as Honduras.” And I said, “Well yes, but in Mexico I am not your daughter”.

[Victoria]: “In Mexico I am not your daughter,” she said. And the truth was that she could be safer there. She left to pursue her studies in the summer of that year, planning to return to Honduras eventually.

In december 2015, Berta the daughter went to visit her mother. Her siblings, who were going to school in Argentina, also came back after being absent from Honduras for two years.

But even though they tried to enjoy that time together, it was impossible to ignore the danger that continued to surround them. Around that time, release was granted to a hitman who, according to testimonies by people in the area, had been paid to kill Berta.

That’s why, as 2016 began . . .

[Berta]: Between the end of January and the beginning of February, my mom began making a public denouncement . . .

(SOUNDBITE DE ARCHIVO)

[Berta Cáceres]: We are being subjected to harassment and illegal detentions by employees of DESA, of the DESA company, of the Agua Zarca hydroelectric project.

[Berta]: I think she also had it very clear that something could happen to her. Well, she would always say to us, “Here, I will either be dragged through the courts or I will be killed.” So I would say no, stop saying that because nothing was going to happen to her, I said she had a lot of recognition, so . . . so, no.

[Victoria]: On March first, 2016, after Berta’s children had left, a forum began that had been organized by COPINH in La Esperanza. The idea was to meet for three days to discuss energy proposals that might work as alternativs to the hydroelectric plants.

One of the people present at that meeting was Gustavo Castro, another environmental activist from Mexico and director of the organization called Otros Mundos. Gustavo and Berta had met in 1999 at a reunion of several movements and ONGs in the continent. This is Gustavo.

[Gustavo Castro]: I thought she was very, very smart, very cheerful, very much alive, with a lot of energy, but above all very intelligent. With a lot of commitment. To her people, a lot of commitment to the social movement.

[Victoria]: After that, they continued to meet at different reunions and mobilizations, and they became good friends. That’s why Berta had invited him to the forum, and when the day’s work was done on March second, she invited him to stay at her house so they could continue to plan the next day’s activities. That sounded like a good idea to Gustavo. They went to dinner and arrived at her house at around ten o’clock that night.

Berta’s house was located in a new neighborhood in the suburbs of La Esperanza, where there were very few buildings. Gustavo was aware of the threats against Berta, so he was surprised to see that the house had no security—just a wire fence around it and a gate at the entrance. But well, he trusted that Berta had everything under control.

After talking for a while, they each went to their room. Gustavo stretched out on the bed. It was more or less 11:30 p.m.

[Gustavo Castro]: A while later, you heard noises and then you could hear the knock on the kitchen door . . .

[Victoria]: For a moment Gustavo didn’t know what it was, but that doubt soon passed. People had made their way into the house.

[Gustavo]: One of them comes into my room and others go to . . . to Berta’s room. I was not aware of how many there were, just one, the one who opened the door to my room and aimed a firearm at my head.

[Victoria]: It was a man with his face uncovered.

[Gustavo]: Just then I heard Berta, she was calling out, “Who’s there?” And the sound of struggling with the doors of her room. And at the end I heard the shots fired to kill her and then they started shooting at me to kill me.

[Victoria]: Gustavo had jumped to the side of the bed to shield himself. Fortunately, the bullet just grazed his head near his ear, and one hand. He was still for a moment, pretending to be dead while the killers left.

[Gustavo]: And then Berta called out to me, once they were gone, she yelled, “Gustavo, Gustavo!” and I went to her room to see her.

[Victoria]: She was lying on the floor covered with blood. Gustavo knelt beside her and was able to sort of lift her up a little. Berta asked him to get his cell phone, call the father of her children and tell him what had happened.

[Gustavo]: And that was when, minutes later, she . . . she died.

[Victoria]: At that moment, Berta, the daughter, was in Mexico City. She had spoken with her mother early that evening. She got a phone call from one of her uncles in the early morning hours, giving her the terrible news.

[Berta]: No—it can’t be. That’s, no—I don’t believe it, right? Because—it’s like—no.

[Victoria]: She didn’t cry in that moment. She hung up and lit a candle.

Later she spoke to her younger sister, who lived in Argentina. Someone had told her that there had been an attempt on her mother’s life but that she was wounded.

[Berta]: She seemed to imagine that mom was in the hospital and that she would pull through. I said, “No, Laura, she has died. So then we have to go because we need to—to start denouncing what had happened.

[Daniel]: They had to demand justice for their mother’s assassination. And despite the risk, the best course was to do that right there in Honduras.

We’ll be back soon.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the pause, Berta Zúniga learned of her mother’s assassination in the early morning hours of March, 2016.

[Berta]: I practically did not even cry.

[Daniel]: But her reaction was more than staying still.

[Berta]: From the moment they gave me the news, I felt a new strength. I felt, I don’t know, something incredible. It was as if I was super stoked, so, so, so . . . .

[Daniel]: And she moved very fast to get everything ready for her trip back. The authorities were already starting the investigation. The body would be taken to Tegucigalpa for an autopsy, evidence would be collected at the scene, testimonies would be taken. But in Honduras, as in so many other countries in the region, anything can happen during an investigation: hiding evidence, making things up, distracting attention to irrelevant things, procuring false witnesses.

That’s why Berta had to be there as soon as possible, and together with her siblings she had to take control of the situation.

Victoria continues the story.

[Victoria]: Berta wanted to be in Honduras—and now—, but booking a direct flight to Tegucigalpa was difficult. The best she could get was one stopover in San Salvador, continuing on. But the flight from Mexico City was delayed, and when she finally arrived late in the afternoon of March third, she had missed her flight to Honduras. That was when she exploded.

[Berta]: I started crying, I was so mad—crying because of the anger I felt because I had been left high and dry. I said to myself, darn, I can’t get there, and I knew that my mom’s body was in autopsy in Tegucigalpa and that it was going to be taken to La Esperanza, so I wanted to get to Tegucigalpa to travel with my mom’s body.

[Victoria]: She even thought of going by land and crossing the border, but that would still take almost six hours. There was no other choice. She had to remain at the airport and wait for the first flight out to Tegucigalpa.

[Berta]: It was horrible because I couldn’t sleep, and besides, I would turn on the TV and they were all talking about . . .

(SOUNDBITE DE ARCHIVO)

[Journalist]: The assassination of Berta Cáceres has shocked the word.

[Journalist]: And it has produced the mobilization of human right organizations, that were in place awaiting the arrival of her body at the morgue in Tegucigalpa.

[Victoria]: She spent all night at the airport, and the next morning she was able to catch a flight. Once in Tegucigalpa, a friend picked her up to take her to La Esperanza. The body was there already, and preparations had begun for the funeral.

Her siblings arrived from Argentina a couple of hours later.

[Berta]: And they were in bad shape, I mean very bad. At that moment, all my sadness went away, everything, and I started comforting them.

[Victoria]: But she felt there wasn’t much time; they had to act fast.

[Berta]: We got together right then and there and said, we are going to give a press conference, on our own. We are going to put out a press release, we are going to say this, this, this, and this.

[Victoria]: The press conference was scheduled for the next morning.

[Berta]: We denounced the state Honduras was in, we said that had been a political crime, that it was the DESA company, that . . . well, that was like all we wanted to say.

[Victoria]: They demanded justice. They didn’t want to witness what they had already seen happen in crimes against so many other activists in the country.

[Berta]: Here, they kill people like dogs and the impunity is shocking. So many people have died here that way, you see? And we, well, we were aware of that. We grew up in those struggles and we had a clear idea of those things.

[Victoria]: And the thing is that, since the coup in 2009 to that date in 2016, over one hundred activists had been murdered in Honduras and in almost all those crimes, no one was ever punished.

Berta’s family also used that press conference to insist that the Agua Zarca project had to be cancelled and the area had to be demilitarized. But they knew that carrying on their mother’s struggle placed them in even greater danger now.

[Berta]: I had never felt afraid at La Esperanza. This is my hometown and I felt . . . well, I was scared. I felt that . . . somewhere, somehow, we would be killed. But we said, no, we’re giving it all we’ve got, right? Against that murderous system.

[Victoria]: The official investigation conducted by the authorities started pointing toward Gustavo Castro, the only witness to the assassination. They were treating him more like a suspect in the crime than like another victim of the attack. First, they questioned him for 48 hours and then they stated that he was not allowed to leave the country. And he wasn’t the only person close to Berta who found himself in that situation.

[Berta]: They began to investigate all the people at COPINH, questioning them for over eight hours.

[Victoria]: And in some cases, with nothing to eat and no rest.

The authorities began leaning toward two main hypotheses: one was a crime of passion. That someone who had had a relationship with Berta was involved in the matter. The other was that the crime had been due, supposedly, to internal conflict within COPINH who would take over the leadership of the organization. And although they admitted the possibility that Berta’s work might have something to do with the assassination, that was not the main hypothesis.

[Berta]: So then we began to say that we had no confidence at all in the State, so then what could we do?

[Victoria]: Around that time, there was a big buzz about the independent investigation that had taken place in Mexico over the disappearance of the students at Ayotzinapa. Berta’s family, COPINH and other NGOs started asking the government and international organizations to form a similar group with experts from other countries.

The Interamerican Commission on Human Rights backed the proposal, and so did the United Nations and several European States, including the Vatican.

But the Honduran State refused.

Even so, the international pressure seemed to work. After almost a month of preventing him from leaving the country, the Honduran Public Prosecutor’s Office finally released Gustavo Castro. They later raided some of DESA’s offices and confiscated USB memory sticks, cell phones. In addition, they hired a telecommunications company to intercept the cell towers near Berta’s house and tap the phone lines that were there that night.

With the information they collected during May of 2016 . . .

(SOUNDBITE DE ARCHIVO)

[Journalist]: Two months after the assassination of prominent environmental activist Berta Cáceres, the Honduran authorities announced this Monday the arrest of four people allegedly implicated in her death.

[Oficial]: Four persons have been captured, who were allegedly linked to the assassination of environmentalist Berta Cáceres.

[Journalist]: The four men, among them one army major and one retired military officer, were arrested during Operation Jaguar conducted by the technical agency of criminal investigation and coordinated by the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

[Victoria]: The persons arrested included a member of the military and one of the alleged hitmen who entered Berta’s house that night. The other two were linked to DESA: one was the manager of social and environmental affairs of the company, and the other was Douglas Geovanny Bustillo, a former member of the military who had headed the security unit at DESA until months before the crime. According to evidence held by the prosecution, these persons had been in contact with the killers, they met with them and they were near Berta’s house that night. DESA denied having any connection to the murder.

The brother of one of the suspects was captured as part of that same operative, and during the months that followed, the police arrested three more people who were suspected of completing the group that killed Berta.

[Victoria]: With these arrests, the government stated that justice was being served. The Public Prosecutor’s Office delivered detailed evidence, and the arrests were legalized. The investigation was over. Now it was just a matter of awaiting the trial.

Berta’s family and COPINH did not dispute that the persons arrested were the actual perpetrators. But they did demand that the investigation continue in order to unearth who the intellectual authors were. Although they had the right, as victims, to see the complete case file, the prosecutor’s office did not grant them access to all the information, to each of the pieces of evidence they had collected. Even though this is something basic in order for legal proceedings to continue in any court case.

This, of course, created a lot of doubts regarding the investigation. For this reason, and even though the State continued to refuse to back any independent investigation, the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights and other international organizations created GAIPE, the International Advisory Group of Experts, to investigate the Berta Cáceres case. This was in November of 2016, eight months after the crime, and it was made up of five attorneys from three countries. Among them was this person:

[Liliana Uribe]: My name is Liliana Uribe, I am a lawyer, human rights defender and social investigator.

[Victoria]: Liliana is Colombian. She has worked for almost thirty years with human rights organizations in her country and other parts of the world. She had been with Berta Zúniga, the daughter, at a meeting of social movements some time back. Because she was so well known internationally for her work, she was invited to be a part of GAIPE.

When she met with the other four attorneys, their starting point was based on a key issue: although criminal investigations are conducted for a specific event, such as a robbery, for example, Berta’s case could not be treated as just a murder. In other words, justice in the case of Berta’s murder did not depend solely on the events of the night of March second. In order to get there, it first had to be placed within a broader context of systematic violations of human rights to which she, the COPINH, and the Lenca people had been subjected.

So the first thing GAIPE did was to get full documentation on COPINH, its importance in the Honduran social movement, and the battles it had fought for almost 25 years. Then, they went to the area where the organization was working to speak to the leaders, the people who lived there, people who supported the struggle for their rights. And people who knew Berta and had worked with her.

At the same time, says Liliana, they met with a DESA attorney who offered her collaboration in the process, as well as with functionaries for the authorities who were carrying out the investigation. But the latter, says Liliana, had an attitude . . .

[Liliana]: . . . that may have been sort of respectful, but at the same time sort of like, hm, we don’t care what you people are going to say, or do—you know? Everything is clear in our minds, we don’t need anything from you, we’ve got everything under control. Besides, they had evidence.

[Victoria]: The evidence that they still hadn’t handed over. From that point on, GAIPE organized all those interviews and gathered testimonies at the public hearings from the people who had been detained. They had a pretty clear view of the case. They didn’t need too much more to complete the report and publish it when finally, between September and October of 2017, the Public Prosecutor’s Office gave them access to the evidence.

[Liliana]: And really, once we had access to the evidence in the file, and once we examined it, that was the biggest surprise, because we said, now how is all this evidence here broken down?

[Victoria]: In other words, the Public Prosecutor’s Office had put together its case with specific points, and it pointed quite clearly to the responsibility of the persons who had been arrested. But the information they had pointed to something much larger and much more damning—and not just regarding Berta’s assassination.

Let’s go by parts.

You recall that the raid of the DESA offices and the searches of the people arrested had resulted in finding USB memory sticks, computers, and cell phones. The total amount of information to be found there was huge—calls, emails, chats.

[Liliana]: This was quite a challenge for us—a very big challenge: to complete the exercise of reading all that information. It was very, very delicate work, very serious, very detailed.

[Victoria]: That’s when they became aware of a communication network among DESA partners, directors, and people in the area of Agua Zarca who worked or collaborated with the company.

[Liliana]: All that host of communications was laid bare and explicit. So that is where we start establishing those, sort of, different levels of involvement.

[Victoria]: It was evident, for example, that DESA was surveilling Berta constantly, clearly seeing her as their enemy.

[Liliana]: They had a level of infiltration by people who were paid by them to deliver extremely detailed information on Berta Cáceres’s every move, as well as of other members of COPINH.

[Victoria]: And when she says “extremely detailed,” that is no exaggeration. Here is one of the messages from one of the chat groups. It is from May 31, 2015. The person writing was an employee of DESA identified as Executive III. What you are going to hear are the exact quotes from those chats and emails, read by an actor.

[Executive lll]: Today at 09:30, the coordinator of COPINH, Bertha Isabel Caceres Flores, entered, accompanied by members of that NGO: Aureliano Molina Villanueva, Tomas Gomez Membreño, Sotero Chavarria, foreign journalists, as well as NGO people step by step . . .

[Victoria]: And he goes on and on providing details. In addition, you could see right there how they were planning judicial attacks.

[Liliana]: The network of lawyers they used to persecute Berta in the judiciary was astonishing. It was astonishing to see how they acted, the matter of corruption of judges.

[Victoria]: And of the media as well.

[Liliana]: In other words, they had media outlets paid to disparage COPINH and make their actions look dishonest when they really had not been like that at all.

[Victoria]: This is another message, written two days after a demonstration by COPINH in February 2016. The person who wrote it was another employee of the company, identified as Public Relations I. GAIPE concealed the names of the people who had not been arrested in order to back the presumption of innocence. That’s the “beeps” you’re going to hear.

[Public Relations I]: I asked— I asked (beep) to make sure the information was not published until we give them the green light.

[Victoria]: He’s referring to instructions he gave a journalist from a local channel. Executive III responds:

[Executive lll]: “Instead of asking a journalist not to publish a story, I think it’s better to instruct them what they should include in their story and what the message should be”.

[Victoria]: Now, as regards the way they treated the indigenous people—

[Liliana]: It’s shocking. They don’t consider them human beings. Reading those chats, I felt like—I said, but what, what times are we living in.

The way indigenous people are treated is—I don’t know, like non-people, and much less like people who have rights.

[Victoria]: This, for example, was sent by Executive I in October of 2012.

[Executive l]: “Those s.o.b. Indians, let them kill each other.”

[Victoria]: Months later, he wrote:

[Executive I]: Those s.o.b. Indians won’t stop fucking (beep) my father . (beep) talking to the Minister of Security (beep) to go get those Indians out of there for us”.

[Victoria]: And he added:

[Executive l]: “Y’all done fucked up today if private property was invaded.. . . I’m going to hire a sniper”.

[Victoria]: A sniper. In another chat in 2013, Executive I wrote this:

[Executive L], “These Indians think the women are going to become infertile because of the dam.”

[Victoria]: These things were proof of everything Berta and COPINH had been denouncing for years. Things that DESA had simply denied—in fact, with the support of media outlets. It all pointed to a structure inside the company that was there to repress any opposition to the project, by all possible means.

All this evidence also helped GAIPE connect the dots directly between those executive and Berta’s assassination.

[Liliana]: We were able to identify a certain moment when the plan to kill Berta was aborted. This was around the beginning of February. And it happened because of visits to La Esperanza made by several of these hitmen.

[Victoria]: That had been confirmed by their testimonies. In addition, on February 16, Bustillo, DESA’s former head of security, wrote this to an executive of the company:

[Bustillo]: “Mission aborted today. It could not be done yesterday. I’ll wait for what you said because I don’t have any logistics, I have zero.”

[Victoria]: The exchange between these two individuals didn’t stop there. They spoke again on March 1, and they met the following day. After that meeting, Bustillo had phone contact during the day with the hitmen, and Berta was murdered that night. Hours later, at six o’clock in the morning, this man spoke with the company executive once again.

It would later be made known that Bustillo was the person who commanded the hitmen. And that in November 2015, when GAIPE inferred that planning of the assassination had begun, Bustillo received a payment of thousands of dollars which he was unable to explain where it came from, bearing in mind that he was unemployed.

GAIPE published the results of its investigation in November of 2017.

In the report they explain that the official records of the searches are not consistent with the material they received. In other words, certain devices that had been recorded were missing. But they make it clear that even with just the information they received, they can affirm that Berta’s murder was planned by DESA and that the executives were aware at all times of just what was going on.

[Liliana]: We submitted evidence that would allow the Public Prosecutor’s Office to undertake an investigation. We consider that it is basic proof—enough, in fact, to convict.

[Victoria]: Because the authorities themselves were in possession of the evidence.

[Liliana]: What we say there really is no fabrication, nothing coming from anywhere except what we found in that evidence that was duly and legally gathered by the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

[Victoria]: Although that report by GAIPE focused on Berta’s case only, Liliana says all that sea of information held by the Public Prosecutor’s Office includes clear evidence of other crimes. To mention just a few, there is conspiracy, payment of bribes, and even the creation of armed criminal groups.

But getting back to the specific case of Berta, once the report had been published, COPINH and the family continued to exert pressure to make sure that the process moved forward and that the intellectual authors were arrested.

On March 2, 2018, precisely on the second anniversary of the assassination…

(SOUNDBITE DE NOTICIERO)

[Journalist]: And in Honduras, authorities have arrested the alleged intellectual author of the murder of environmentalist Berta Cáceres. He is Roberto David Castillo Mejía, former executive president of Desarrollos Energéticos S.A.

[Victoria]: Castillo is that very Executive III who appears in the report.

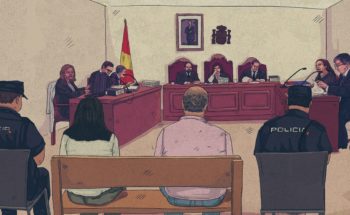

Almost nine months later, seven of the first eight people arrested were found guilty by a Honduran trial court. And one year later, they were sentenced to thirty to fifty years of prison.

You might think that an important battle was won against that impunity which in Honduras has become the rule. The judiciary had validated GAIPE’s report, which, in addition, revealed a great deal of evidence that could lead to other investigations. All that remained now was to await Castillo’s trial and the arrest of other members and partners of DESA.

But of course, it wasn’t that simple. Three years have gone by, and although Castillo is still detained, his trial is just starting. The defence has delayed it in many ways, and the pandemic has not helped any to speed things up. We contacted his attorneys to talk about the case, but they opted not to make any statement.

During all this time, his defense team has gone about conducting a big campaign to discredit GAIPE investigation, and trying to prove that Castillo and DESA are innocent. They’ve even published messages exchanged between him and Berta in an attempt to demonstrate that the relationship between them was friendly.

But for daughter Berta Zúniga, it would be absurd to think they were friends. Her mother had told her that they communicated and that Castillo did act friendly. But even so—

[Berta]: She would say, this guy is the most dangerous one of all because he does not insult me or anything, he just tells me. I know that you are at a meeting in Zihualtepec right now.

[Victoria]: That is, at a meeting of social movements where he was not invited.

[Berta]: How did he know about that? He said it so that she would know she was being watched.

[Victoria]: It made sense for Castillo to behave that way. He’s a former military officer who was trained at West Point, one of the most prestigious military academies in the United States. He later returned to Honduras and held an important position in military intelligence, and he formed part of the organization that controlled electric power in Honduras, which also belongs to the military. From there he went on to DESA to get that image of a successful businessman that his defense team is so determined to maintain.

Castillo belongs to a social class in Honduras that historically has not had to worry about obeying the law. This is something Liliana saw in the messages they reviewed with GAIPE.

[Liliana]: They were so convinced of the impunity that they spoke with complete abandon. That is, so blatantly that it was shocking, you know? People almost never get to those levels. If we at GAIPE had not insisted on that debate later, this would all have remained in the hands of the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

[Victoria]: And nobody would have gone to the trouble of analyzing all that evidence they had.

Another lawsuit was filed against Castillo, in 2019, for the crimes of abuse of authority, counterfeiting documents, fraud, among other things. According to the investigation, while working in the government he helped award a state contract to a company created less than a year before by two people who worked for him. That company was DESA, and the contract was for the construction at Agua Zarca. To date, this trial is still pending.

[Berta]: Sometimes I feel as if . . . as if a part of me has become resigned to the impunity, has become resigned to, well, many things. But then I say, okay, what would my mom do if, let’s say I was the one who had been murdered? I know she’ll always be an example for us—to get activated in our struggles.

[Victoria]: Berta Zúniga has been the general coordinator of COPINH since May of 2017. Now, at age thirty, she continues the struggle to advance the rights of the Lenca people, the recognition of ownership of their lands and the protection of the environment. Despite constant accusations, threats against her life and the life of other leaders, they refuse to give up. Right now, DESA continues to hold permits to build hydroelectric projects on the Gualcarque River.

[Daniel]: After Berta’s assassination, at least 29 activists have been murdered in Honduras. The country to date continues to be one of the most dangerous places in the world for environmental activists.

The Agua Zarca project is halted, but COPINH has already filed a new lawsuit to achieve permanent cancellation of the construction permits that are still held over the river. They also filed a lawsuit for negligence against the Dutch Development Bank for agreeing to finance the project despite being aware of the complaints against it.

This story was produced by David Trujillo and Victoria Estrada and reported by Chiara Eisner. It was edited by Camila Segura and by me. Desirée Yépez did the fact-checking. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri. Thank you to Jorge Despethen for the help with this episode.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante includes Paola Alean, Nicolás Alonso, Lisette Arévalo, Jorge Caraballo, Aneris Cassasus, Xochitl Fabián, Fernanda Guzmán, Rémy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Barbara Sawhill, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.