Pigcracy – Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I am Daniel Alarcón.

Today we start with him.

[Daniel Adum]: My name is Daniel Adum Gilbert.

[Danie Alarcón]: Daniel was born in Guayaquil, Ecuador. And he has been an artist for twenty years. Although well, actually he defines himself more as…

[Daniel Adum]: More than an artist, I believe I am an anti-system in a way, right? I’m like a… an alien, sometimes I think I am, hmm.

[Danie Alarcón]: His works are not the typical ones that you would find in an art gallery. He has more of a street style. Let’s see: paint a wall with the phrase “HAHAHAHA!”, Collect trash from the beach and put together a sculpture. But he also has works that are more political. For example, he used to paint the flag of Guayaquil, but he removed the colors. In shades of gray, as a kind of protest against the government of the day.

Daniel Adum does things like that. And his work has made him a recognized artist in Ecuador.

But let’s go back to August 2004, when Daniel was unknown. He was finishing his studies in visual communications at the university and at the same time working in an advertising agency.

One day, without warning, his bosses came to the office and announced that all employees had to take a written test. That it was part of a new protocol they wanted to implement.

They were simple questions, exercises to measure their abilities to solve problems, or to see how they would behave in stressful situations. And with the answers…

[Daniel Adum]: They were going to measure the psychological state of the workers by means of their calligraphy.

[Danie Alarcón]: But instead of filling out the test with his common handwriting…

[Daniel Adum]: I did a typographic work. I did a thing that was very scratchy.

[Danie Alarcón]: Each letter was different: some larger, some thinner, some very close together. He did it for fun, but when his bosses saw that…

[Daniel Adum]: They just said… they said, “Well, you have to go. You can’t work here”.

[Danie Alarcón]: They fired him on the spot. Daniel didn’t care too much; he was frustrated with that job and he really didn’t like what he was doing. So, without saying more, he picked up the materials he was working on – printed and digital – and left.

A few months later, one of those things that he took with himself would turn his city, Guayaquil, on its head.

Our producer, Lisette Arévalo, tells us the story.

[Lisette Arévalo]: On the day he was fired, Daniel came home and put all the things he had brought from the office in his study, which was in the basement. That’s where he drew, painted, and experimented with different materials, colors, and techniques. And in those days…

[Daniel Adum]: Stencils were in vogue.

[Lisette]: Stencils, that technique that uses a template to make letters, numbers or drawings on walls, on sidewalks, even on T-shirts.

[Daniel Adum]: It was not such a mainstream fashion. But things related to street art were starting to happen. I had already been doing some things on the street.

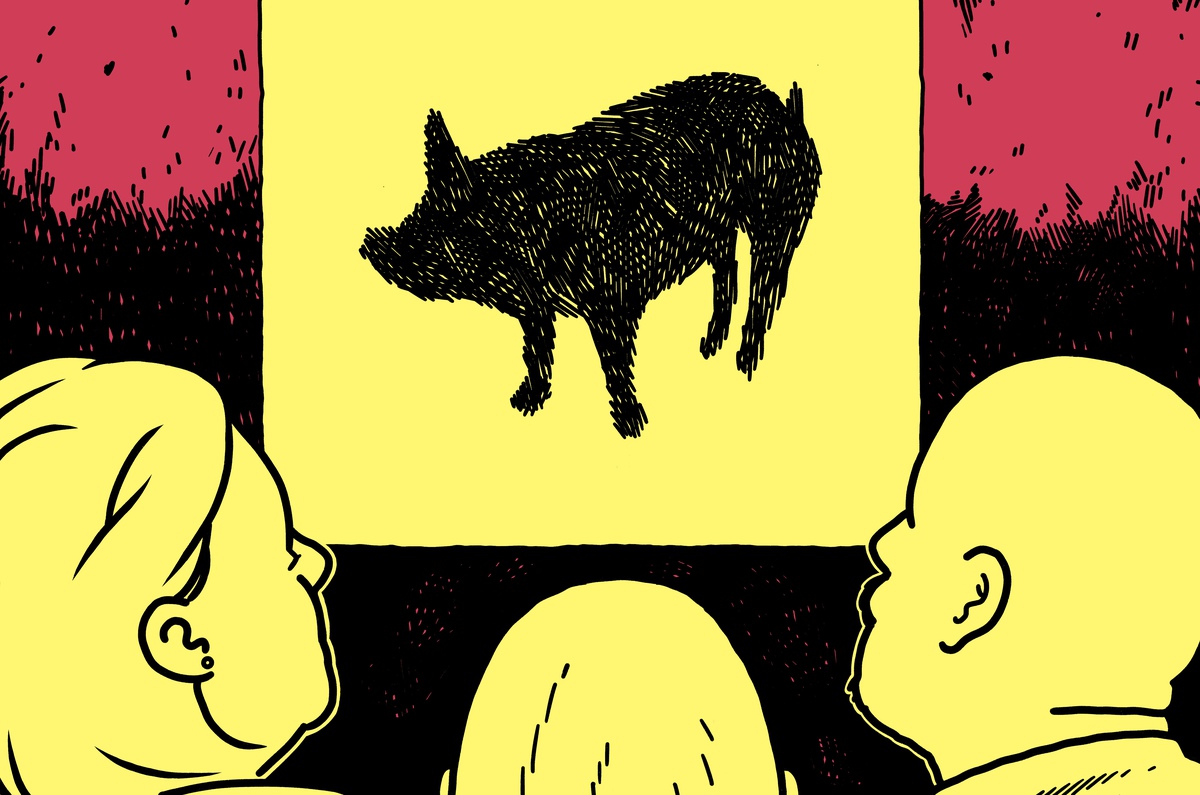

[Lisette]: With more free time, Daniel dedicated himself to experimenting with the technique. One day he began to look at the papers that he took from the agency, to see if he could find a design that would help him make a template. He found the image of a pig that had been downloaded from the internet for a restaurant logo.

[Daniel Adum]: It is a small pink pig, beautiful, harmless, very friendly.

[Lisette]: The little pig is smiling. In fact, it looks a lot like the movie Babe from the mid-nineties. He is so adorable. This one that Daniel chose…

(SOUNDBITE FROM THE MOVIE BABE)

[Daniel Adum]: It has a special perspective because it is not completely sideways, it is like a three quarters view, diagonal.

[Lisette]: This pig needs to be described. First, it’s not a cartoon, it’s not Porky or anything like that. Rather, it looks like a farm animal catalog photo. We see him from above, standing on all fours, his body diagonally, and he seems to be looking at us. His muzzle is pointing up, the two ears are up, and only one of his eyes is visible. You can also see a part of its twisted tail.

With that image Daniel began to create his template for the stencil.

[Daniel Adum]: So, I traced the pig, I … I transferred it to the cardboard using carbon paper, tracing forcefully so that it withstands … the use.

[Lisette]: He cut out the template and only the silhouette of the pig remained: the four legs, the tail, the snout and only one of the ears is visible. It was pretty large, about half a sheet of cardboard. It took him about fifteen minutes for this entire process.

Then he bought a couple of fluorescent pink and black spray cans and called his girlfriend to help him paint on the streets.

It was October 9, 2004.

[Daniel Adum]: I waited until it was late enough so they wouldn’t get me in trouble.

[Lisette]: To avoid getting into trouble.

[Daniel Adum]: It was midnight, maybe, and I went out to paint everywhere, to rehearse, right? To see how this technique worked and do it, do it, do it all over Samborondón.

[Lisette]: Samborondón is a residential area with large urbanizations a few minutes from Guayaquil. At that time, 2004, there were few houses, but most of those who lived there — as it is now — are among the wealthiest in the city. Most of what you had at the time were empty lots with billboards announcing the next big construction project.

[Daniel Adum]: There was not even a traffic light, there were no policemen, there was nothing. In other words, you were the owner and at night you did whatever you wanted here.

[Lisette]: It was an ideal environment to experiment with stencils without being seen or disturbed by anyone. Daniel remembers that night as one of pure fun. Some kind of a party.

[Daniel Adum]: Instead of drinking and getting wasted you are painting “ta-daa”. And you feel this kind of rush of energy and adrenaline, of painting in the city, because you know that it is not legal anyway and you are damaging the public space.

[Lisette]: That night he painted about 10 pigs on poles, traffic signs, house walls and vacant lots. And he had such a good time that he decided that he would continue to paint the same figure in different places in Guayaquil.

His only intention was to practice his technique, look for good places, and see if the pigs would have an impact on people.

[Daniel Adum]: I’m going to paint here and here, but I’m sure people see this while driving and something happens. “What is that little pig?” Or … or it provokes you in some way or whatever, right? I … I wasn’t sure what would happen.

[Lisette]: It was an experiment without a hypothesis or a clear intention. That’s why he only told his girlfriend what he intended to do and no one else.

For a month, Daniel loaded his car with the pig’s template, a camera to take photos of the results, and cans of black, red, and white spray paints. He chose those colors because they were the ones that contrasted the most with any surface.

If he found a place that seemed like a good location and visible from the cars, Daniel would stop his car, get out and paint a pig.

[Daniel Adum]: The pigs follow some kind of a circuit that was the same circuit that I was basically moving through, right?

[Lisette]: In other words, the journey he took to go see his girlfriend, to drop her off, go to a meeting, go to a party.

[Daniel Adum]: In all those circuits, which were basically, uh: Sambo to the Center, from the Center to Urdesa, from Urdesa to Sambo. I painted all those areas.

[Lisette]: Sambo is Samborondón. Urdesa and the center were very active areas during the day, but very deserted at night. More than anything for security reasons: at that time the news about assaults, robberies and kidnappings were everywhere and people preferred to stay home and not take any risks.

Little by little, the city began to see more and more pigs on the external walls of schools, clinics, and houses. You could find them at tunnel entrances, on monuments, on traffic signs.

Daniel painted a total of about thirty pigs and stopped.

[Daniel Adum]: I get tired of myself and the things I do very quickly. I do one and then I do another one and then I change. I’ve been like this all my life.

[Lisette]: He stored the template in the basement of his house and, for him, that was the end of the story with the pigs.

And without further ado, he continued with other art projects.

After a month or so, Daniel was at home working on his computer when he received an email from his sister. It was a chain email, the kind we received in the early 2000s with jokes, friendship messages, or photos and videos of landscapes with cheesy, pseudo-inspirational phrases. Not so different from the messages that go viral on WhatsApp today.

But this one was a warning. It said:

[Daniel Adum]: “I am writing to you because of the following, yesterday I was told something that has not appeared in the press, but it is good that you know. Two of the leaders of these Latin Kings youth gangs have reportedly been murdered in Spain. It seems that the murderer is a high-class guy from Guayaquil”.

[Lisette]: The Latin Kings, that gang that was born in the United States, and in the nineties was replicated in different countries, such as Ecuador and Spain. In those days, you could hear about them in the news almost daily. They were linked to car thefts, murders, assaults. In Guayaquil, above all, they were seen as responsible for any violent act in the city.

The mail continued:

[Daniel Adum]: “The fact is that members of this band have come from Spain and have joined with those who were already here and it is rumored that they are going to retaliate against four hundred people from Guayaquil: two hundred for each death.”

[Lisette]: It said that the gang members were drawing profile views of pigs of three colors on the walls and that each one had a meaning.

The black one…

[Daniel Adum]: “Means death.”

[Lisette]: The red one…

[Daniel Adum]: “Means violation.”

[Lisette]: The white one…

[Daniel Adum]: “Means scare. In parentheses, they are going to be scared.”

[Lisette]: Later, the mail said that all of Samborondón was full of those drawings. And it ended:

[Daniel Adum]: “I really don’t know if this whole story is true, but it’s worth being cautious anyway.”

It was like wow, how funny. What … how crazy! How can people believe this … this note? Wow, people’s creativity is amazing.

[Lisette]: Daniel tried to track down who had written the original email, but couldn’t find it.

[Daniel Adum]: This had a giant queue of replies. In other words, there were eight hundred thousand emails down here and up here. And it was kind of like huge blocks of one email after another bam, bam, bam, right?

[Lisette]: He printed the email to keep it as a reminder of what his work was accomplishing and left it at that. He did not answer his sister or tell her that what the email said was a lie.

What Daniel didn’t know was the terror that this rumor was causing among Guayaquil residents. Especially among children and adolescents who, upon receiving the email, did not take long to talk about it with their friends and schoolmates. That’s how everything got out of control.

We asked listeners of Radio Ambulante in Guayaquil, and many remembered it. They sent voice messages to us. Like a broken phone, the rumors went beyond the Latin Kings.

[Cristina]: We all started talking about the email and about the pigs.

[María]: They said this gang used the pigs as threats.

[Marcelo]: They were supposed to be satanic rites.

[José]: Others said it was a symbol of witchcraft.

[Dyana]: The black one meant that on day there was going to be a plague, the red meant there was going to be a killing.

[Arianna]: A bomb explosion, rape.

[Francisco]: In those days we were pretty afraid.

[Francisco]: It was a feeling of … of anguish, right?

[Danie Alarcón]: A pause and we will be back.

[Spanish Aquí Presents]: This message comes from Spanish Aquí Presents, an Earwolf podcast. Each week this podcast talks about Latino comedy, culture and experiences with fascinating guests such as Luis Guzmán, Aimee Carrero – Disney’s first Latina princess – and Pitbull. Hosted by comedians Carlos Santos, Raiza Licea, Oscar Montoya, and Tony Rodríguez. Listen to Spanish Aquí Presents on your favorite podcast application and subscribe so you don’t miss any episodes.

[Up First]: While you were sleeping, news was happening all around the world. Up First is NPR’s podcast that keeps you informed of big events in a short time. Share ten minutes of your day with Up First, from NPR, Monday through Friday.

[Squarespace]: This message comes from an NPR sponsor, Squarespace, a website builder providing clients easy-to-use, professionally designed templates. Join the millions of graphic designers, architects, lawyers and other professionals who use Squarespace to establish their presence online. Visit Squarespace dot com slash NPR for a free trial. And when you’re ready to launch your page, use the NPR code to save ten percent on your first website or domain purchase.

[How I Build This]: What does it take to start something from scratch? And what does it really take to build it? Every week on How I Build This, Guy Raz talks to the founders of some of the most inspiring companies in the world. How I Build This, from NPR: Listen and share with your friends.

[Danie Alarcón]: We are back on Radio Ambulante, I am Daniel Alarcón. Before the break we were talking about the panic that an email that began to circulate in Guayaquil had created. It was an alert: it said that the colored pigs that were appearing in some neighborhoods of the city were a threat from the Latin Kings.

At first, this panic was not evident all over the city. Let us remember that Daniel Adum painted the pigs in residential neighborhoods of middle and upper-class families in Guayaquil. And also, that it was 2004 and the Internet was not as massive as it is today. It was a luxury that only some could afford. In other words, it was a scare for the wealthiest families. Especially for those who had children who went to private schools, because that’s where the rumor spread the most.

Perhaps for this very reason it didn’t take long to reach the national media. By early December of that year, two months after Daniel had painted the first pig, things like these were heard on the news:

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: The appearance of pigs drawn in different sectors of Guayaquil are being investigated.

[Journalist]: They say the Latin Kings gang has started a process of violence identified in a very special way.

[Journalist]: The Latin Kings and Ñetas gangs are at odds and have marked the territories where they will commit crimes.

[Journalist]: The drawings of pigs have alerted students.

[Journalist]: The police will continue to investigate the matter to restore calm to citizens.

[Danie Alarcón]: In other words, a young artist paints about thirty little pigs on the wall just because, and in a matter of weeks these little animals are transformed into an imminent threat.

Lisette picks up the story.

[Lisette]: The media chose to publish the news before fact-checking the information. They began to do several interviews with people who had seen the pigs. Like this lady.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Woman]: Groups of… of boys who do bad things, who have put pig signs in different parts of Guayaquil to supposedly do some damage, but it is not really known what is at the heart of the matter.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Lisette]: And these teenagers…

[Kid]: People think that in the sectors where the pigs are, supposedly, they are going to kill.

[Kid]: These are groups that have really threatened and have in distress the city of Guayaquil, Spain and the United States.

[Lisette]: They also spoke with government authorities, who asked people to remain calm. This is the governor of that time Efrén Rojas.

(SOUNDBITE FROM ARCHIVES)

[Efrén Rojas]: I have already ordered Colonel Cadena to deploy an operation and security because there are young people, there are boys, there are girls and they need to be protected.

[Lisette]: Additionally, Coronel Luis Cadena affirmed the police had a security and intelligence plan already in place.

(SOUNDBITE FROM ARCHIVES)

[Luis Cadena]: We have already put police personnel in those schools where we think these groups could approach … these youth groups that are acting against Ecuadorian citizens.

[Lisette]: The police also went to the schools to give safety talks and try to calm down the students and their parents. But that was not enough. The news of the killer pigs was everywhere.

I spoke with several Guayaquil residents who were teenagers at the time. Mariella Toranzos, for example, remembers that when she was about 16 years old, one night she was at a party with her classmates, dancing, peacefully…

[Mariella Toranzos]: Suddenly cell phones began to ring urgently. I remember that I answered my father and he told me: “Look, they said in the news that something is happening with … with some boys and some gangs so I’m going to pick you up now.” And the same happened to all my friends.

[Lisette]: Other people told me that as a result of the pigs, their parents stopped giving them permission to make any plans: going to shopping centers, to parties at their friends’ houses, to the movies. Many didn’t even want to send them to school

For this reason, several schools in the city had to send messages explaining the security measures they were taking. Others chose to evacuate students and decided to suspend classes as a precaution.

All this panic caused by just thirty pigs painted by Daniel Adum.

They also told me that those who continued to go to school were very nervous. If they saw a painted pig on a wall on their way to school, they would hide under the bus seats. As if just by seeing them they could be marked as the next victim.

Giuliana Dávila was 16 years old and remembers that next to her bus stop there was an empty lot.

[Giuliana Dávila]: And that wall was full of pigs so when the … the bus dropped us off there, we all ran home because we were afraid of getting kidnapped, or that a bomb would explode or something.

[Lisette]: Something similar happened to José Andrés, who was also 16.

[José Andrés]: Upon seeing… the pigs painted on a house I chose to walk faster because I didn’t know if at that moment, they were going to rob us.

[Lisette]: I even heard of a family that moved because there was a pig painted outside of their house. But the story that surprised me the most was the one that María Silvia Aguirre told me. She was nine years old at the time and she was in the school choir. At the beginning of December, when the whole topic was in the news, they were going to perform in a shopping center.

[María Silvia Aquirre]: So, we took the bus from school and on the way, we saw a little black pig on a wall and everyone started saying that they were going to kill us all while we were singing. I tried to ignore everyone but it was inevitable, I was scared and I continued to be scared the entire song.

[Lisette]: Imagine, a group of children trying to fine tune the notes with their voices while their legs were shaking.

As Guayaquil residents grew increasingly scared of pigs, most of the media did not do the obvious thing to solve the mystery: talk to the direct source, the Latin Kings. Although one outlet said it “consulted” with one of them, they did not give details nor did they air the interview.

On the other hand, two members of the media spoke with the gang expert, Nelsa Curbelo, and this is what she replied:

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Nelsa Curbelo]: The drawing does not correspond to the gang members’ way of communicating. This is done with templates. Gang members communicate with graffiti and then they sign it, which identifies who is making a threat.

[Lisette]: But apparently no one paid attention to that. The fear by then was out of control.

Daniel had no idea about all this coverage, or everything that was happening in the schools, or the collective panic. Although he received the newspaper at home, he did not read it, nor did he watch television or the news. He was not interested.

But on December 6, 2004 – almost two months after painting his first pig – he received a call from El Universo, one of the largest newspapers in the country. The reporter told him he knew he was the author. Daniel replied…

[Daniel Adum]: No, I don’t know. I know who it is and I know it is an art project.

[Lisette]: He told them that he could not tell them who it was, but that the artist would reveal it soon, in the cultural section of the El Universo magazine. And he stressed one thing:

[Daniel Adum]: It’s an art project and it’s nothing related to what they are talking about.

[Lisette]: He denied it over and over again and hung up the phone. Daniel was surprised by the call and he didn’t quite understand how they found him. It occurred to him that perhaps someone from the newspaper saw a pig that Daniel painted in the office of a friend of his, asked who the author was, and figured it out. But he stopped thinking about it and that night he went to a party.

The next day, December 7…

[Daniel Adum]: I was coming home from partying that night and I went in, I took the newspaper, I opened it and, bang! Front page.

[Lisette]: A large photo of two little black pigs that he had painted at the entrance of a tunnel. It had this title:

[Daniel Adum]: Police investigate origins of graffiti.

[Lisette]: Daniel started reading right away.

[Daniel Adum]: The police in Guayaquil are investigating versions of graphics of pigs painted in some sectors. And they have been linked to alleged threats from gang members.

[Lisette]: He opened the newspaper and looked for the longest article. The note repeated the same thing that the newspapers and newscasts had said in the previous days: that there was an email that was spread among young people, that everything was a supposed revenge of the Latin Kings, that each color meant something different, that hundreds of Guayaquileños were destined to die, but anyway.

He kept on reading, and there was something new there: his name. It said that someone had linked him on an email to the pigs, that he had been contacted, but he had denied being the author.

Daniel couldn’t believe it. His first reaction was one of overwhelming happiness.

[Daniel Adum]: My feeling was like what a great thing, I mean what … what a great thing, it was madness. It was like wow, I’m the best. Right? I mean, I did something colossal, like… Imagine only 25 years old and I had a painting on the front page of the most widely read newspaper in the country. It was such an achievement, wasn’t it?

[Lisette]: But that did not last long.

[Daniel Adum]: And obviously I did feel a bit scared. And like what the fuck, right? What, what, what, what’s going on in this city?

[Lisette]: And he began to ask himself several questions.

[Daniel Adum]: How was it possible that I, the author of the image, was so happy at home, while a part of the city was scared to death by a pig painted on the walls? Where was the police? When would they come and question me? How can people be so naive to believe the story the media is selling?

[Lisette]: Daniel put down the newspaper and went to sleep for a while. But a few hours later his father woke him up because his aunt was calling him. She worked at the Guayaquil mayor’s office.

[Daniel Adum]: She said: “Dani, please help me. I mean, I know you know, if it was you, don’t worry that we are going to make sure that you are safe and that things work out for the best. But help me, ok? Tell me who was it”.

[Lisette]: Daniel was silent. On the one hand he wanted to continue with his original plan. But on the other, he did not want the chaos and panic to continue.

[Daniel Adum]: Because it was not my intention in any way. It’s enough. I don’t want anyone to die, or for anyone to go to prison, or for schools to close, or anything like that, it’s not what I want.

[Lisette]: So, he told his aunt.

[Daniel Adum]: “Okay fine, it was me. I painted that. It has nothing to do with the things they are talking about. It is a work of art, it is a project and blah, blah ”

[Lisette]: Hi aunt thanked him and told him not to worry, she would take care of everything. She asked him to come to her office the following day very early in the morning to fix it and explained the protocol that she had in mind for Daniel to follow.

[Daniel Adum]: “We are going to send you with cameramen, lawyers, security, video so that you can erase all the pigs. We are going to send a press release with the photos”.

[Lisette]: In addition, she told him that he would have to pay a fine of one hundred dollars for municipal damages and make a public apology. Daniel accepted. Partly because he was somewhat afraid of a possible legal mess.

[Daniel Adum]: Sure, if someone died back then they would blame me. Or if they wanted, they could claim I was the leader of the gangs, who knows.

[Lisette]: I mean, they could make up any story. But whatever happened, he was calm.

[Daniel Adum]: Because I knew the truth, right? I was not painting with bad intentions. “Oh, I’m going to scare all of Guayaquil, ha, ha, ha.” If I had been interested in disturbing the public or wanted to generate some kind of collective paranoia, the stupid idea of painting pigs on the walls would never have occurred to me.

[Lisette]: At seven in the morning the next day, Daniel and his girlfriend went to the mayor’s office to carry out the removal of the pigs. Daniel’s aunt and her team were waiting for them.

When they entered the communications office, Daniel watched several televisions, recording the news continuously. His aunt told him that they had recorded everything about the pigs on television channels and showed him some of the material. It was the first time Daniel and his girlfriend had seen it.

[Daniel Adum]: Since it began to appear in the media and the email arrived and all of that, I could not believe it. From then on it was like wow! a movie.

[Lisette]: But he felt his aunt support. She had everything set up so he wouldn’t get into trouble.

[Daniel Adum]: I mean, what I needed from… from the institution that was handling the matter was security, right? Make sure that nothing was going to happen to me.

[Lisette]: Because if someone could make up a story like the one of the post office and cause such a collective panic, anything could happen in Guayaquil.

They talked for a few more minutes and her aunt told him that the mayor’s office had bought cans of gray paint for Daniel to paint over the pigs and erase them. She told him that a car was waiting for him outside to take him to all the places where he had painted but first, he had to pay the fine. Daniel accepted. He paid. Before leaving the office, his aunt gave him a copy of the newscast’s recordings, and they said goodbye.

[Daniel Adum]: They put me into a municipal car and took me for a walk around the city with a lawyer, a cameraman.

[Lisette]: The cameraman was going to record the entire act of deleting the pigs to send it to the television channels. And well, the lawyer, it was never very clear why he was there. But Daniel thinks maybe they sent him to watch him and make sure he did his job.

[Daniel Adum]: I truly felt like a Rockstar. There in the municipality, right? I was there with my hat, my glasses. Protected and painting. And with cameras, everything was very funny.

[Lisette]: And it was the first time that Daniel was being filmed painting, as if he were a famous artist. But it was different, of course they recorded it here.

[Daniel Adum]: Doing such a stupid act as painting with gray. So yeah, it was kind of like what a joke, huh?

[Lisette]: They began to tour the city, going to the places where Daniel remembered painting little pigs. And he was surprised to see that some were crossed out with an X, and others had already been erased.

[Daniel Adum]: And not only had they erased them, but they had put a heart, love, peace on them, as messages contrary to what the media story said.

[Lisette]: I took Daniel and his girlfriend about three hours to erase the pigs. For him, all this was a pretty absurd and even childish punishment.

[Daniel Adum]: It even seems ridiculous to me. There was no need to go to delete anything. It’s just a way to show power or control. But what Guayaquil needed was for someone to come out and say: “It is not what they are talking about, it is simply an artist painting. Ready, for something else”. There was no need to go and erase anything or put up all that show.

[Lisette]: What’s more, if the mayor’s office wanted to make him feel bad for erasing his work, they couldn’t. Daniel didn’t even feel nostalgic erasing them.

[Daniel Adum]: Because it’s a stencil, you know? And you can do it again so easily. It is not something achieved with a high level of techniques and with too much patience or something difficult for me to do. I do it quickly (snap fingers), I do it very fast and very easy, right? You also know that whatever you put on the street can disappear right away. That’s life, the dynamics of street art.

[Lisette]: When Daniel finished the alleged punishment, he looked at his cell phone and realized he had dozens of missed calls: It was the media that wanted to interview him. That the mayor’s office had sent a press release announcing that they had finally solved the mystery of the murderous pigs and they had revealed his name. It was as if they wanted to set him as an example in front of the entire city so that no one would think of doing something similar.

At 25, and by accident, Daniel had achieved something that many artists take years to achieve: have everyone talk about him.

[Daniel Adum]: And I also received some privileges by not being taken prisoner. By not suffering major consequences other than paying a hundred dollars and almost, almost being rewarded with what people call fame.

[Lisette]: Daniel agreed to be interviewed, but first he planned what he was going to say. Because even though the pigs were just an experiment to practice his technique, he felt that he had to give a bigger and more pompous justification

So, he used the opportunity to criticize something that had always bothered him: the way of doing political propaganda in Guayaquil.

[Daniel Adum]: If they can come to the city at election time and wallpaper the city, paint murals, put stickers on your cars without asking your permission, do whatever they want. I can also go out as a citizen and paint my pigs and… or whatever I want.

[Lisette]: As he was preparing to give interviews, Daniel came up with the name of the project: Chanchocracia. And so, he began to be known in the media. He told me that the name came up because in the early 2000s, wealthy politicians referred to the “cholocracia” to speak disparagingly of politicians without money. So, he used that term and changed cholo for chancho. Nothing more.

And that speech was well received by some media. Such as this interview with Carlos Vera, a political journalist.

(SOUNDBITE FROM INTERVIEW)

[Carlos Vera]: And what does chanchocracia mean, Daniel?

[Daniel Adum]: I think it’s a metaphor for… to talk about the … the kind of people who are totally… unreasonable, I don’t know.

[Carlos]: Are they the ones who rule the country?

[Daniel Adum]: In a way, it can be, yes.

[Lisette]: Daniel went on to say that, due to the political situation at the time full of corruption scandals, this interpretation was correct.

When Daniel remembers those interviews, he claims that he missed to chance to say more.

[Daniel Adum]: I think I fell short of explaining it. I don’t have a… like I wasn’t able to clarify everything, because it wasn’t so clear to me at that time.

[Lisette]: Because when he went out to paint his first pig, he had no other intentions other than having fun.

But perhaps the most absurd thing was the reaction some of the media had. Let’s recall that few of them made an effort to fact-check the meaning of the pigs, such as corroborating the rumors with the Latin Kings. Nor have I been able to find any media that has investigated the origin of the email that spread so much terror. Instead, they just criticized what Daniel did.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: If this young man caused such chaos as the one that occurred, like the one we saw, why didn’t he warn from the beginning that it was an art expression?

[Journalist]: He does not own the city to put his pigs all over public spaces, even worse if we are in the regeneration of the city. Nowhere.

[Journalist]: However, when Mr. Adum claimed that he… did it against dirtiness, you are getting the walls dirty, Mr. Adum.

[Lisette]: Daniel did not care much for these comments. After all, he knew that in a way they were right because painting on city walls without a permit was wrong.

But he also knew that what really bothered them was the chaos he had created – because, of course, he was not the first to use graffiti. And although it makes him sad to think about the fear that so many people felt, he knows he had nothing to do with it.

[Daniel Adum]: I always try to emphasize that. Fear was not created by me; fear was created by you. I painted a pig.

[Lisette]: At the time, with the things you heard about gangs, robberies and assaults, insecurity was an issue present in all homes. That is why the email and the story were so popular: it resonated with the ongoing conversation among Guayaquil residents.

A few days later, Daniel came up with the idea of making t-shirts with the pig and selling them at his front yard. It was there he realized that many people weren’t upset. On the contrary, they kept on congratulating him.

[Daniel Adum]: Dying of laughter, enjoying it: “How cool! Awesome, I want one, give me two, three for my daughter, for my niece. She was scared to death. I’m going to take one for her so that she gets scared and gets a kick out of it”. I mean, it was a blast. I mean, those who were scared to death were later dying of laughter and wanting to buy t-shirts. What I understood is that from fear to consumption there’s only one step.

[Lisette]: The shirts were sold right away and from that day on, Daniel became known as “the pigs guy.”

[Daniel Adum]: It’s like, what a cool thing to have been able to get tattooed on the psyche of this city that way, right? With something as simple as a picture of a painted pig.

[Lisette]: And it’s true. It still happens that when they recognize him on the streets, in meetings or at parties, they approach him to take pictures with him or to tell him how they experienced the Chanchocracia panic. And everyone laughs and ha, ha, ha, and most of them forget that they were really afraid.

[Danie Alarcón]: To this day it is not known who sent the mail that caused all this hysteria. Daniel Adum Gilbert wrote a book about what happened. It’s called: “The true lie of the Chanchocracia.”

Lisette Arévalo is a producer for Radio Ambulante. She lives in Quito. This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas and myself. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with music by Rémy Lozano. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Jorge Caraballo, Aneris Casassus, Victoria Estrada, Xochitl Fabián, Fernanda Guzmán, Miranda Mazariegos, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Desirée Yépez.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.