The Stories of My Name | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: If you listen to Radio Ambulante or El hilo, you probably already know that we’re obsessed with politics—not just in Latin America, but also in the US. This year’s presidential election is not only one of the most crucial in history, but also one of the tightest. There’s a lot at stake, and the outcome will likely come down to just a few states.

This time, over 36 million Latinos are eligible to vote, and to better understand them, we teamed up with our partners at Noticias Telemundo to create a new series: El Péndulo. Join journalist Julio Vaqueiro as he visits five key states: Pennsylvania, Florida, Nevada, Arizona, and North Carolina. Listen to El Péndulo: Voto Latino 2024, a podcast by Noticias Telemundo and Radio Ambulante Studios, available on our Central series channel on iHeart Radio or your favorite podcast platform.

This is Radio Ambulante, I’m Daniel Alarcón.

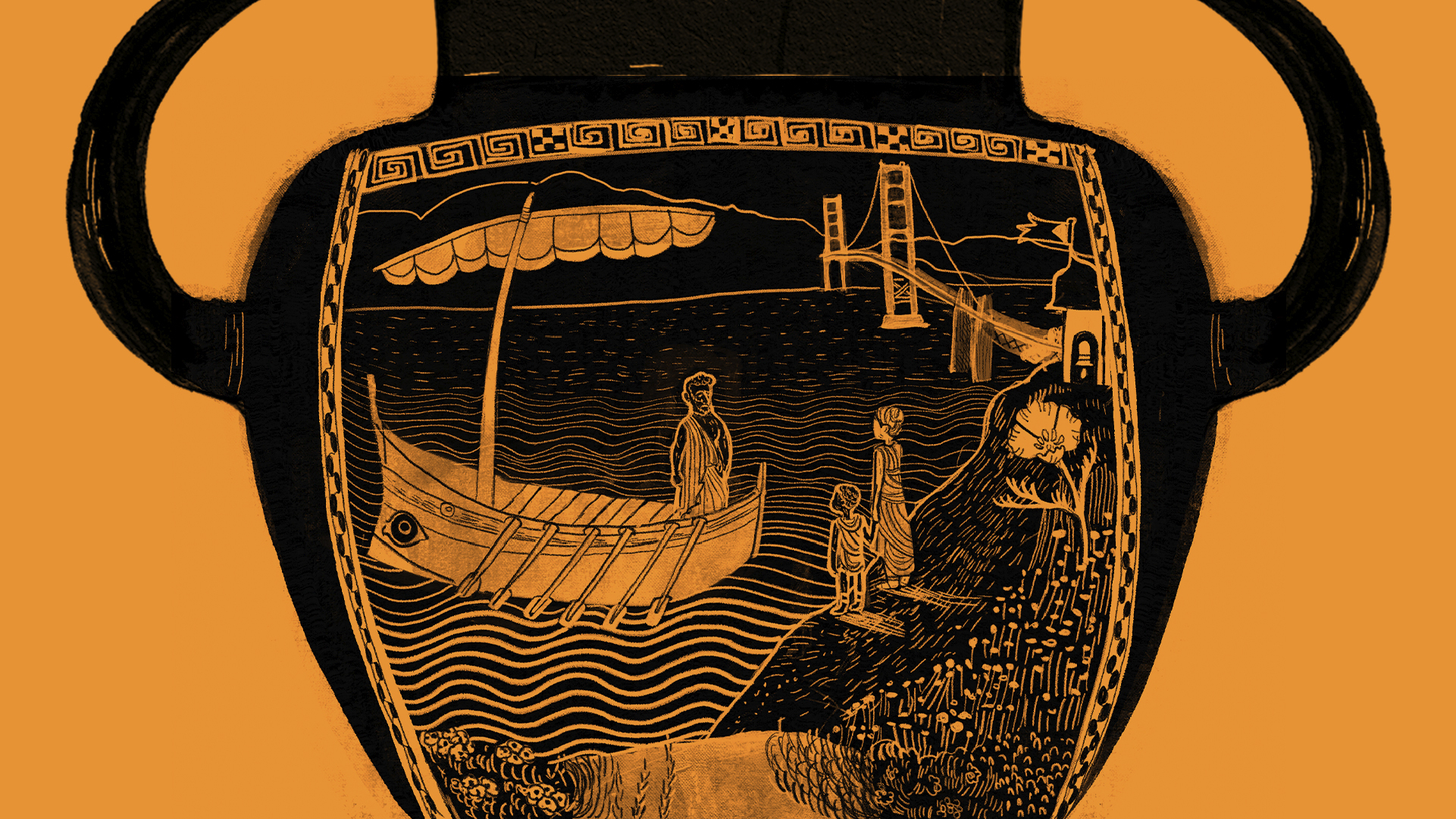

Today’s story begins in the late 1980s, in a small mobile home near Palo Alto, California. Nick Casey grew up there, listening to the stories his mother Kaye told him.

[Nick Casey]: We were in the living room together, and she would always look for a photo album from her years before I was born, when she worked on cargo ships. Then she would tell me about all the countries where she had traveled.

[Daniel]: Places like the Philippines, Turkey, Japan, or Puerto Rico.

[Nick]: She had a basket full of coins and bills from all the countries she had visited. And I always counted those coins, because we were poor, and I thought it was a fortune.

[Daniel]: Kaye had Nick when she was 38. Before that, she worked at sea for a decade. She was also a waitress, accountant and painting salesperson. And earlier, she was married. She spoke of her past with nostalgia, but also with satisfaction; it wasn’t a place of regrets, but of adventures.

[Nick]: My mother always told me my story and her story as something very mythical.

[Daniel]: And Kaye was also talking to Nick about his past.

[Nick]: Yes, it was like a fairy tale that told me about my origins, and also to introduce to me who my dad was.

[Daniel]: Because his father didn’t live with them. He worked as an engineer on a ship and spent most of his time at sea. Although he and Kaye were not married, he came to visit from time to time—sometimes every six months, sometimes once a year. And during the periods when he was gone, that were eternal for any child, Nick depended on what his mother told him about that mysterious man.

His name was Nicholas. And his last name, Wimberley.

Kaye gave Nick that name too, except that Wimberley became his middle name, not his family name. She told him that that way, if she died one day, he would have a way to find his father. And for a family name, Kaye gave him hers: Casey.

In addition to explaining the history of his name, Kaye told Nick stories about his father.

The first of them began very far away, on an island in the middle of the Indian Ocean, called Diego García. There, one day in 1983, Kaye met Nicholas.

[Nick]: So I always thought that in this tropical place, very far from everything, on an island—it must have been a very, very long romance.

[Daniel]: A romance between a white woman and a black man. Kaye did not make it clear that this romance was actually a one-night stand. It was a children’s story, after all. She told Nick only the essential part: that he was conceived on that paradise island.

The second of the stories began shortly afterwards. Back in California, Kaye discovered that she was pregnant. She had always wanted to have a child. When she gave birth, she wrote a letter to Nicholas telling him the news in the hopes that he would read it. There was no response, but three months later, Nicholas called. He had disembarked, so they agreed to meet in Oakland.

[Nick]: In a café, according to my mom. And as she tells the story, she brought me along, of course. He’d had no idea of her pregnancy. And she remembers that he had two cups of coffee in his hand, and when he saw her, his hands started to shake.

[Daniel]: It was obvious that Nicholas had not read the letter, and also that the dark-skinned baby was his.

[Nick]: But according to my mother, he also tried to look for a birthmark that he said all his children had.

[Daniel]: It was a mark on his leg, and Nick did have it.

[Nick]: And well, sure, then he acknowledged me.

[Daniel]: A few hours later, Nicholas went back to the sea. Nick and Kaye were left on their own. And that way, on their own, they were fine. This seemed to be the moral of the stories Kaye told Nick about his father. They lived in California, Nicholas lived on a boat, each lived their own life, and they met only from time to time.

[Nick]: What you have to understand is that my mom and dad were like children of the 60s, from the era of free love, drugs, and everything, and according to them, they were free as the birds. So they lived the lives they wanted.

[Daniel]: And perhaps to reinforce the lessons, Nick remembers that Kaye also read him stories about heroes without fathers. Like The Odyssey, where the character Telemachus spends the first twenty years of his life without seeing Ulysses, his father.

[Nick]: I think that was precisely because she wanted me to be proud of my background, of my story as well. And yes, she did realize that those narratives, those stories you have about yourself are important.

[Daniel]: Because with them, Nick could make sense of his reality—a reality very different from that of other children. And at first, when he was very young, Kaye’s stories did help him understand his father’s sporadic absences. But after a while, he disappeared. And this time it looked like he wasn’t coming back. It was then that Nick began to wonder more about that man. Who was he and where did he come from? How much did his mother really know about him? So he began a quest that would lead him to become the person he is today.

We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Our producer Pablo Argüelles picks up the story.

[Pablo Argüelles]: Nick remembers that when he was about six years old, there were days when the phone rang at home. Kaye answered…

[Nick]: And I always noticed a change in her expression; she smiled. And I knew it was my dad.

[Pablo]: So they got in the car and drove to one of the ports in San Francisco Bay. There, Nicholas was waiting for them. He had just disembarked.

[Nick]: But it was different from what you imagine when you talk about a meeting between a father and his son. Because it’s not like when your dad comes home from work every day and you see the same face. Instead, I always had to remember what his face looked like, what his voice sounded like.

[Pablo]: To Nick, he seemed like a giant with very dark skin, with a mustache and sometimes a beard.

[Nick]: And also, always telling jokes, always laughing, always telling stories. So my dad would arrive like some kind of magical pirate.

[Pablo]: A pirate who was always drinking from a small bottle.

[Nick]: I remember he told me, “Oh, that’s my medicine!”

[Pablo]: Kaye clarified that it was rum. But anyhow, the pirate also walked around with a first aid kit to treat his wounds.

[Nick]: He said to me, “Those are the things you have to do if you are a man.”

[Pablo]: And he seemed to have so many treasures. Once, he gave Nick fifty dollars.

[Nick]: I had never seen a $50 bill in my entire life. Well, I was very happy, very happy. But I think that may have been the only financial support we ever got from this man.

[Pablo]: Visits could last hours or a couple of days. But there was one thing that never changed:

[Nick]: We didn’t know when he was going to show up in our lives, or when he was going to leave.

[Pablo]: The first seven years of Nick’s life were like that. And his father never really got involved in how Kaye raised him. Until one day, around 1991, Nicholas saw a photo of Nick surrounded by his friends from school.

[Nick]: And he saw the picture… the school that I loved, and he was a little suspicious. We saw a change come over his face. The thing he saw was not that all the students, the children, were very happy, but that they were all white.

[Pablo]: And Nick was the only black kid.

[Nick]: He told my mom that it wasn’t good, that I needed to be with other black kids.

[Pablo]: The thing is, Nick’s world was his mother’s world.

[Nick]: So I was born and raised in a white world, in a country dominated by white people, from television to the presidency. And there came a time when I also thought I was white.

[Pablo]: But now Nick understands well what his father meant.

[Nick]: Without contact with my own people, I was going to have the same fear that much of America has of black people, which is that we are violent, or that we are poor, or that we are thieves.

[Pablo]: And although Kaye reminded Nicholas that day that it was easier to travel the world than to actually raise a child, deep down she also understood what Nicholas meant. Because just out of the blue, she decided to take Nick out of his school and enroll him in another one where the majority of the students were black. It was in East Palo Alto, a city that had the highest per capita homicide rate in the entire United States at the time. But that didn’t seem to worry her. She was determined. She was like that.

Shortly after Nick turned seven, his father visited them again.

[Nick]: He arrived the way he always did, I don’t know from what part of the world.

[Pablo]: And they went to a restaurant. There, he told them something that Nick would never forget:

[Nick]: That he had killed—killed someone. And we were shocked. What had happened? Then he told us a story about…

[Pablo]: He told them that a friend had arrived at his house, fleeing from a man. So Nicholas let her in. But the man stayed outside, yelling, banging on the door, getting louder and louder. It looked like he was going to knock it down. Then Nicholas pulled out a gun and shot through the door. The man died.

[Nick]: But he told us, “Everything is OK.” We’re like, “What do you mean everything is OK? You killed someone.” He told me, “Well, hmm, well, I was defending myself. And the judge recognizes that. And also my lawyer has told me that the most I am going to have to spend in jail is going to be like two years, but maybe less.”

[Pablo]: He reassured them that he would return once he was released from prison. With that promise, they headed to the port of Crockett, near San Francisco, so that Nicholas could embark again. Nick remembers the thick fog that covered the pier and the hug his father gave him. They said goodbye, sure that they would see each other again.

Months passed without news of Nicholas. Meanwhile, at his new school, Nick was starting to have problems. His classmates asked him why he spoke like a white person.

[Nick]: Well, I thought I spoke normally, but no, to them I spoke like an extraterrestrial or something. And they asked me, “Are you adopted?” I say, “No, no, no, I’m not adopted. My mom is white. My dad is black.” “But where is your dad?”

[Pablo]: Nick had no answer. The children also made fun of him because he didn’t know how to play basketball. And when one of them found out that Nick’s middle name was Wimberley, he said:

[Nick]: “That’s a stupid name! How can anyone have that name?” Kind of like, “What the hell is that name?” I don’t know, but it was something an eight-year-old wouldn’t normally say. And he kept after me. And one time he found me in the bathroom and started hitting me very hard.

[Pablo]: That day, Kaye picked up Nick, saw he had been beaten, and asked him who it was.

[Nick]: She looked for the boy and threatened him, saying that if he ever hit me again, she was going to hit him too, but much harder. In a way that she wasn’t going to leave bruises or anything. That was very surprising, not only for me but for the other students, because they heard about what had happened. And well, this image of a, well, a white woman threatening a black child was not a very good or very nice image.

[Pablo]: Until then, race for Nick had been about the type of hair you have or the color of your eyes. But to his classmates, it seemed to be something much deeper.

[Nick]: They had lived a racial experience that was very different from the experience a white person lives.

[Pablo]: An experience based on racism that was like a wound that was reopened with each act of violence committed in the United States against Blacks. In 1991, when Nick was six years old, a group of white police officers in Los Angeles beat a black man, Rodney King, almost to death. A man recorded the scene with a camcorder and the video was broadcast on television around the world. A year later, when the four police officers were acquitted in a trial, several protests broke out in the city.

[Archive soundbite]

[Man]: No justice, no peace! No justice, no peace!

[Nick]: We all saw that on television.

[Archive soundbite: Protests]

[Pablo]: Black and Latino communities took to the streets. There were fires, looting…

[Nick]: And I believe it was during those years that I lost my innocence about what race was like in the United States. So that’s when I started to realize that I wasn’t white, that I was black.

[Pablo]: It was a painful situation. Because the person who could have taught Nick the most about what it meant to be black in America was now gone.

[Pablo]: Months turned into years. About five years. And still no news from Nicholas. Kaye began searching for him in the California prison databases.

[Nick]: And I saw that his full name, according to her, was Nicholas Wimberley Ortega.

[Pablo]: Nicholas Wimberley Ortega. As we said, Nick also had that name, Wimberley.

[Nick]: But Ortega? I asked her, “Why Ortega?”

[Pablo]: Kaye said that Nicholas had told her he had been born in Cuba, or that his parents were from there. And although neither Kaye nor Nick had heard him speak Spanish, he claimed that he could.

[Nick]: And he told us that he could speak some Korean, some Japanese, a little bit of various indigenous languages that he learned, presumably, when he was a child. We didn’t know what was true and what was a fairy tale.

[Pablo]: Nick was about 12 years old at the time, and didn’t even know where Cuba was. As for the name “Ortega,” he had only seen it on a brand of Mexican hot sauce. But now it was a new clue to his father’s history.

[Nick]: That was part of who he was. And, well, it has to be a part of who I was too.

[Pablo]: First white, then black. And now Cuban. Latino.

[Nick]: One thing my mom explained to me once when we were talking was that a person could be black and Latino at the same time. So that was a more transverse identity. So you could be like white, mestizo, mulatto, black. All, all of them Latino.

[Pablo]: In 1997, Nick earned a scholarship to a private high school. There he had the option to choose a language and he didn’t think twice about it: he wanted to speak Spanish. In that class, he met other Latinos who, like him, did not know the language of their parents and grandparents.

And very soon, in the spring of 2001, when he was 16 years old, a unique opportunity came to him. The school choir had obtained special permission to tour Cuba. Nick was not part of the choir, but the director told him that he could help them as a translator.

[Nick]: Saying he had spoken with my mother, and he thought that more than the others in the choir, I deserved to go to Cuba to get to know my country of origin.

[Nick]: Normally when an American comes to Cuba, the first thing they see are the cars from the 50s and 60s. But for me, the thing that first caught my attention was the fact that Cubans looked like me.

[Pablo]: In Havana it was very easy to imagine his ancestors walking through the streets. Perhaps he had already even crossed paths with an uncle or a cousin without meaning to or knowing it.

[Nick]: There was no way to look for them, to find them with only one name: Ortega. Because how many Ortegas are there in Cuba?

[Pablo]: Lots of them. But it didn’t matter. It was enough for Nick to know that maybe they were there. During the concerts, his job was simply to introduce the group and the repertoire—from a Leonard Bernstein mass to “Guantanamera.” They traveled from Havana to the Bay of Pigs, then to Trinidad and Cienfuegos. And there, one night, in a hot, humid theater, in front of about a thousand people…

[Nick]: After I introduced the choir in my very, very gringo Spanish, someone called out, someone called out saying, “Well, this guy is obviously Cuban, he’s one of us!” And at that moment, I felt right at home.

[Pablo]: Nick returned to the United States after about ten days. He was very excited. What that person had said was almost as if he had been given his Cuban passport. But the recognition was also painful, because his father had still not shown up. The trip to Cuba was also a reminder of everything Nick didn’t know about his father. So he decided to confront Kaye.

[Nick]: I began to pressure her to give me more precise information about who exactly he was. She told me that, from to what she remembered, he grew up in Arizona, but he also grew up, according to him and according to her, on an Indian reservation in the United States.

[Pablo]: A Navajo reservation, probably in Arizona.

[Nick]: I was like, “Well, what does that have to do with the fact that he was Cuban?”

[Pablo]: Kaye’s stories, and by extension Nicholas’s stories, didn’t seem to add up. Kaye didn’t even know Nicholas’s precise age, just that he was older than she was.

[Nick]: I was beginning to doubt the information my mother gave me. And well, I think that reaction hit her, not only because she saw that I was angry, but also because she realized that she truly had no information about this man who was her son’s father.

[Pablo]: About ten years had passed with no news from him. It was likely that he had died in prison or at sea.

[Nick]: So I pretty much gave up the search. But yes, I think there were still ways to find my identity.

[Pablo]: And the first clue to finding that identity was a name: Ortega.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Pablo Argüelles continues the story.

[Pablo]: Nick studied Anthropology at college between 2001 and 2005. And during those years he began traveling frequently around the continent. He went to Mexico, then to Peru, and also to Santiago de Chile, where he studied for a semester. He took the opportunity to go to Argentina and Patagonia and then also to the Amazon. He was traveling with a book by Pablo Neruda, the Odas Elementales, and also with Cien Años de Soledad. It was the cliché of the foreign backpacker that romanticizes Latin America.

[Nick]: Of course, definitely romanticized. Why? Because I didn’t live there. So I was there, coming and going.

[Pablo]: Thinking that one way or another, the region would be part of his life.

When he graduated, Nick decided he would not follow the path of academia. At age 22, in 2007, he found work at the Wall Street Journal as a business reporter in Los Angeles.

[Nick]: But I always had this dream of returning to Latin America. So I went into journalism to be a correspondent, and two years later, a position opened in Mexico City.

[Pablo]: And he got the job.

(Archive soundbite)

[Archival Nick]: Since the start of the Mexican Drug War, villages like this one in Guerrero State were terrorized by organized crime groups. Rapes and killings were common…

[Nick]: My job was to cover what was really happening in Mexico… And well, the business in Mexico, unfortunately, was drugs.

[Pablo]: He was in Ciudad Juárez, Monterrey, Acapulco…

(Archive soundbite)

[Archival Nick]: For The Wall Street Journal, this is Nicholas Casey in Ayutla, Mexico…

[Pablo]: The position in Mexico also included the Caribbean region, so he was able to go to Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and also, of course, several times to Cuba, no longer as the translator of a children’s choir, but as someone who could tell its stories.

[Nick]: I could share with the Cubans I was interviewing because I told them I was Cuban. And as I walked through the streets of Santiago de Cuba, I saw many people who had my father’s face.

[Pablo]: But Nick hadn’t had the hope of finding him for years. At thirty, he was focused on his career, which was getting better and better. In 2015, the New York Times hired him to be a correspondent in northern Latin America, mainly Venezuela and Colombia, but also Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia.

In 2016, he settled in Caracas. Not a week had passed when he attended a Chavista demonstration. He thought he was going to see people burning American flags and hitting piñatas of Barack Obama. But instead he found a crowd dancing to this song:

[Archive soundbite]

[Alí Primera]: Levanten tus manos la bandera de la revolución, América Latina obrera y grita con fuerzas: “Yankee go hoooome, Yankee go hoooome Yankee go home.”

[Pablo]: “América Latina Obrera,” by singer Alí Primera.

[Nick]: All the people dancing, celebrating, it was like a huge party in the street. I remember that one of those Chavistas grabbed me and started dancing with me.

[Pablo]: Even after Nick identified himself as an American, a New York Times reporter.

[Nick]: Even with the Yankee who comes to a demonstration against the Yankees, they are dancing with him.

[Pablo]: It was a moment when he felt welcome. And he loved it. But perhaps this welcome was not only something that Latin America was giving him, but also something that he longed for as a Latino coming from the United States.

Because Nick had not lived there for years, in his country, which was increasingly unrecognizable to him. Donald Trump wanted to be president. Violence against black people continued. And although Nick recognized that Latin America had other problems, just as deep and complex, they were not the ones that had marked him so much when he was a child.

[Nick]: I remember in Venezuela, seeing that sure, there is tremendous poverty, but if you go through those Chavista neighborhoods you see white, black, mixed, indigenous, all kinds of people. It is not like the United States where everything is determined by the issue of race. And that was something very new, very striking to me.

[Pablo]: But the welcome he felt in Venezuela was short-lived. Nick began to cover the crisis in the country—shortages, inflation, social tension, the exodus of thousands of Venezuelans. His articles appeared on the front page of the New York Times, and in October 2016, the Venezuelan government prevented him from re-entering the country and he was forced to move to Medellín, Colombia.

And there, shortly after his 33rd birthday, in 2017, he received a package in the mail. It was a gift from his mother.

[Nick]: A DNA test.

I think she was asking forgiveness for not being able to provide more information about my father. So it was like a symbolic gift. And at first, no, no, no, no, I didn’t take the test because, well, what was I going to do with information telling me I was half white, half black, and that I had ancestry in Africa, and so on?

[Pablo]: But Kaye insisted, and Nick took the test. About two weeks later, the results arrived by email. And they stated the obvious. That on his mother’s side his origins were from Europe, specifically Germany and England. And on his father’s side, from West Africa.

But the most interesting thing was that a list with names of “possible relatives” appeared on the computer screen. Similar to what happens on Facebook. Suggestions of people you may know. And there he saw a photo of a supposed cousin. A black cousin. She was obviously from her dad’s side. So Nick wrote to her through the platform chat. He told her he had been searching for his father for decades.

[Nick]: “And well, according to this, you are my cousin. I don’t know if you would have information about this man. I think his name is ‘Nicholas’ like mine. And if you know more, please write to me.”

[Pablo]: Nick gave her his email. About four hours passed. And then… a message from her showed up in the inbox.

[Nick]: And the first thing she asked me is, “Well, is your father a Wimberley?” And she told me that she was not my cousin, but my niece.

[Pablo]: But also, the message said that Nick’s father…

[Nick]: Was still alive. I was in shock. That‘s not what I had expected to find.

[Pablo]: Nick had already come to terms with the idea that his father had died and that the puzzle would never be complete.

[Nick]: But in a matter of a few hours, online, everything was solved in such a short time. That was the amazing thing.

[Pablo]: After exchanging a couple of messages with his new niece, Nick received a text message.

[Nick]: Saying “Hello, brother! I’m your brother Chris. I live in Los Angeles and I received the email from my daughter. I am here next to your father. And he wants to talk.”

[Pablo]: Chris gave him a cell phone number. It was almost midnight. Nick dialed immediately, and when he heard breathing on the other end of the line, the first thing he said was:

[Nick]: “Dad.” And it wasn’t like a question. It was just to say the word “dad” to my father.

[Pablo]: He needed to reaffirm it. Nick heard his father’s voice, sounding old, like something out of a 1940s movie. He could have recognized it anywhere in the world, even after some 25 years.

[Nick]: He started talking to me as if we had talked the day before. And the thing I remember most was that he wasn’t that surprised that I was calling him. So I was very excited, he was also very excited, but not so surprised by the fact that I had found him after so many years. He told me, “Well, I always knew that you would find me some day.”

[Pablo]: And didn’t you feel a little offended that he said, “I knew you were going to find me?” Because that means you were the one who had to look for him, not that he was looking for you.

[Nick]: Yes… The question is a bit complex. Because, well, I often thought, “Why doesn’t he search for me on Google?” But I… was so happy just to be able to find him. There wasn’t any room in my heart at that moment to be offended.

[Pablo]: But what Nick did have were questions. A lot of them.

[Nick]: Since this man always appears and disappears, I didn’t know whether that would be the last time I was going to talk to him. I wanted to get as much as I could out of this man before he hung up the phone.

[Pablo]: They started the story from the beginning. Nick had as a reference what Kaye had said. So he began by asking his father: Were you born in Oklahoma?

[Nick]: Yes.

[Pablo]: Did you grow up in Arizona?

[Nick]: Yes, that was also true.

[Pablo]: On a Navajo reservation?

[Nick]: Not true.

[Pablo]: It wasn’t true…Then they moved on to the names. First, the first name. Was his name Nicholas? His father told him no, his name was actually Novert.

[Nick]: First thing I learned: my father’s name.

[Pablo]: Now it was time for the surnames. Was Wimberley real? Yes it was. And… Ortega? Novert started to laugh.

[Nick]: And I asked, “Why, why are you laughing?” And he told me, “Well, I…yes, this was one of my names. But I had put it on a driver’s license in the ’70s or ’80s because it sounded so good. And I thought it was very cool.”

[Pablo]: So… had Novert made up the family name Ortega for his driver’s license, just because it sounded cool?

I talked with him to corroborate this, and he confirmed it: the name “Ortega” was an invention for his driver’s license in the state of California. He told me they didn’t ask for any proof, and that he chose that specific name because his childhood neighbors had that family name.

That night, Nick continued interviewing his father. He found out that he had three sisters and two brothers, and that he was the youngest of them all. He also had a dozen nephews and nieces. Suddenly, his family multiplied.

But Nick also wanted to know more about the story that had impacted him so much. So he kept asking. Had his father killed someone? Yes. In self-defense, just as he had told them the first time. And how long was he in jail? Only 30 days. Why then, if it was such a short time, did he not look them up when he got out?

[Nick]: He started telling me things, like my mom didn’t want to see him because she had another boyfriend and wanted to have a family without him, but I know that didn’t happen.

[Pablo]: More than explanations, they sounded like excuses. But Nick didn’t confront him.

[Nick]: I know that after abandoning your own child, it is a difficult thing to explain to your own child. He realized that he was an old man. And maybe the time to really confront him about those things had passed.

[Pablo]: Nick had spent years thinking he was Cuban. He had learned Spanish. He had become a correspondent in Latin America, traveling through the region, risking his life…

[Nick]: Trying to understand and consume and become part of that culture.

[Pablo]: All in an effort to feel closer to his father.

[Nick]: What was I feeling at that moment? I was gaining a father, but at the same time, I was also losing the narrative I had built.

[Pablo]: What was more valuable? Getting his father back or losing the stories he had grown up with? The stories that gave meaning to his identity?

I asked Nick, after these revelations, about the name Ortega, if he still felt Cuban. Without hesitation, he said yes.

[Nick]: And I’ll tell you why. There is a very large diaspora of Cubans. You don’t have to be born in Cuba to be Cuban. You don’t have to speak Spanish to be Cuban, either. So I hope that in that diaspora, this concept of what it means to be Cuban, that there is still a space for a person who thought he was Cuban but was not by… by… by blood, but maybe he was in his soul and heart.

[Pablo]: Before hanging up, Nick and Novert agreed to meet in Los Angeles for Thanksgiving.

Nick flew there from Medellín. The meeting took place in the parking lot of Jack in the Box, a fast-food restaurant.

When Novert arrived, father and son hugged and then went to Chris’s house.

For most of his life, Nick had spent Thanksgiving alone with his mother. But now he was surrounded by his nephews and nieces, his brother Chris, his sister Dakota, and his father. It was a strange feeling. Everyone wanted to know more about him, the new member of the family. And Nick also wanted to let off some steam. He spent a lot of time talking to Chris, the oldest of his siblings.

[Nick]: He could see that I had some sadness about not spending my childhood with my dad. And he told me, “Well, this man, your father, when he was younger and he was my father, that was a very hard life.”

[Pablo]: He told him that back then Novert was very violent, that he fought a lot with his mother, and that when he finally left them to go live at sea, the truth is that everyone felt pretty relieved. I tried to contact Chris to corroborate this, but he did not respond.

[Nick]: Chris said to me, “Well, maybe it wasn’t a bad experience for you and your mom that your father wasn’t in your life when you were a child and vulnerable, and that you can start your relationship with him now that you are an adult and he is old.”

[Pablo]: At that moment, Nick thought of Kaye. For years he had resented that she had not been able to give him more information about his father. But now her stories and her explanations, however incomplete, took on a new meaning, very similar to that of Chris’s words.

[Nick]: What I thought was that my mom had tried to say the same words to me several times. She knew that the man was an alcoholic and had his own demons.

[Pablo]: But Kaye wasn’t telling Nick this. She told him that his father was traveling the world on his boat. And so, with these stories Kaye did not sow any resentment. It was a gift that helped preserve Nick’s memory of the magical pirate and now gave him the opportunity to build a relationship with him.

[Nick]: I realize that it will never be possible to recover the years that we lost. But it is possible to make good use of the years we have left. So that’s what we’re trying to do.

[Pablo]: It has not been easy. Partly because there is little time left. Today Novert is over eighty years old. The distance doesn’t help, either. He lives in Los Angeles and Nick in Madrid, so they talk every two or three weeks.

[Nick]: Sometimes he calls me. And I see his number on the phone and I remember the times I longed to get a call from him, but that call never came… and I can’t answer the phone.

[Pablo]: Nick has to wait a couple of days before returning the call. He says that it’s happening less and less, that he’s still getting used to having his dad back in his life.

[Daniel]: Pablo Argüelles is a producer for Radio Ambulante and lives in Madrid. This story was edited by Camila Segura. Bruno Scelza did the fact checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with music by Ana Tuirán.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Lucía Auerbach, Adriana Bernal, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Luis Fernando Vargas and Desireé Yépez.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

If you enjoyed this episode and want us to continue doing independent journalism about Latin America, support us through Deambulantes, our membership program. Visit radioambulante.org/donar and help us continue narrating the region.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.