Translation – Alias el Cóndor

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Hey, Ambulantes. Last week we started selling tickets for our two live shows in September of this year. Did you know? Have you bought your ticket? Well, here are the details: on Tuesday the 25 in Washington D.C., and on Thursday the 27 in New York. That is in September.

We are very excited to share these stories with you in person, to meet you, to laugh with you. We promise that it will be two nights of surprising, moving, and entertaining stories. Here are the dates again: 25 and 27 of September, in Washington D.C. and New York. To buy your tickets go to radioambulante.org/envivo. Thanks, and see you there!

Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. We’re counting down to the World Cup. There are only days left. So today we’re telling a story about soccer.

But not necessarily the kind of soccer that has beautiful passes and picture-perfect goals. Instead, we’re talking about the other side of Latin American Soccer. A rough, rowdy, aggressive game. That kind of soccer that involves kicking, fouling and winning at all costs.

I went to Chile last year to talk to this man: Danilo Díaz, sports journalist.

[Danilo Díaz]: I was at the newspaper La Tercera. Then I went to the team that founded the magazine Don Balón, where I eventually became the, uh, director. I spent a good part of my career there.

[Daniel]: Now he’s at Radio ADN, in Santiago, and the truth is when I spoke with him, I felt like he was almost like a historian, with an amazing memory for matches and scores and players, the whole mythology of Chilean and Latin American soccer.

And we got together to talk about a complicated period on Chilean soccer. Some controversial matches, some unfair losses and then the reaction.

[Danilo]: So, of course, things were going on in Chilean football so we became “más bandidos que los bandidos” [lit. better bandits than the bandits].

[Daniel]: So, what came next was a period of a lot of corruption. There was this idea that a match wasn’t just won on the pitch, but outside of it as well. And that when it came to winning, well it was worth whatever it took; even more so when you were talking about the national team.

He gave me an example. A story that has been circulating about the Copa América in 1979. Colombia v. Chile. And the Chileans…

[Danilo]: They sent prostitutes to the Colombian National Team. And the players set them up with the prostitutes and took pictures of them. And the next day when they went out on to the pitch with their banner, the pictures were in the middle and they passed the pictures to the Colombians and the Colombian players nearly died. If they didn’t have a heart attack on the pitch….[Laughs]

[Daniel]: There’s no evidence that these pictures exist, but what we do know is that Chile won 2-0.

And well, similar things happened in the local league. The Polla Gol Scandal, for example, in ’86, when they uncovered a ref racket that was manipulating the scoreboards. And to make matters worse, Polla Gol was a state owned company.

That’s how it was.

For example, Danilo also told me about a team from Santiago that was playing outside the city. And it was going alright for them. They were tied. But at one point when there were about only 5 minutes left in the match, the visiting team’s coach let loose a dog that was hiding in a piece of luggage.

The dog ran out onto the pitch, interrupting the game. In the time it took them to catch the poor animal, the match had already ended. So they stayed tied.

Things like that happened at that time. But I don’t want to give the impression that Chilean soccer was more violent of more corrupt than soccer in other countries either. Not at all. There’s also the story of the famous Chilean soccer club that went to play an away game in Asuncion. All of the players on the bus started to feel tired, half-asleep. Why?

[Danilo]: Someone had put sleep aides in…in their food.

[Daniel]: Cheating was rampant in Latin American soccer. For many there remains the suspicion that the 1978 World Cup in Argentina was not entirely above board. Some people suspect that the military junta that governed the country rigged the results of at least one match to favor their national team. And well, maybe the worst case is one from Colombia, in which the ’89 national championship was canceled because drug traffickers rigged matches and even killed referees.

All of this is important in order to understand what comes next. The qualifying round of the 1990 World Cup in Italy. This is Jorge Hevia.

[Jorge Hevia]: The qualifying round for the ’90 World Cup in Italy took place a year prior. The channel decided that I would be commentator for all of Chile’s matches.

[Daniel]: Jorge narrated the matches for the channel TVN: Televisión Nacional de Chile. Now the qualifying rounds are everyone against everyone, but at that time…

[Jorge Hevia]: It was by group. It was a group of…of 3 and 1 out of each group qualified.

[Daniel]: Chile was up against Venezuela and Brazil.

[Jorge Hevia]: So, of course, you’re up against Brazil and they were the monster you had to defeat.

[Daniel]: Brazil: the team that’s always makes it, the only team that has never missed a World Cup. And although this version of the “Scratch” was not Pelé’s, well… Brazil is Brazil.

And Chile, in order to beat them, to move on from this group and make it to Italy, they were ready to do whatever it took, especially because they had not made it to the Mexico World Cup in ’86.

They would play in a two-legged qualifier between the 3 teams. In other words, the teams would face-off twice: one home game and one away.

A little more context. The year before, at the ’87 Copa América…

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: Into the goal box… And a goal for Chile! Really exceptional!

[Daniel]: Chile was beating Brazil 4 to 0.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: Great pass to…Letelier.

[Commentator]: Oooh!

[Presenter]: What a shot from Chile…What a shot! Juan Carlos Letelier passes to Astengo.

[Daniel]: So at the time there was this sense that this Brazil was not unbeatable.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: Chile is going to the semifinals. Chile beats Brazil by a landslide!

[Daniel]: But how did Chile beat Brazil? This is Juan Carlos Letelier, who was Chile’s forward at the time.

[Juan Carlos Letelier]: We must have had 6 or 7 chances. We made 4. Brazil had, hmmm, 10, but we had Roberto. And Roberto blocked everything.

[Daniel]: Roberto Rojas, alias the Condor. Captain of the team, goalie, national idol, considered by many at the time to be the best goalie in Latin America, one of the best in the world.

Danilo Díaz also remembers him.

[Danilo]: Roberto Rojas’ performance was…brilliant. Extraordinary. A point-blank catch, a 1 – 10 match: 10 points. In fact, Rojas is one of the few players I saw given a 10 in the Argentine magazine El Gráfico. What Rojas blocked that day is…outstanding. Brilliant. Not the kind of goalkeeping you see every day.

[Daniel]: His performance was so good, he was hired by Brazil right after.

[Luciano Borges]: Roberto Rojas played for the team in São Paulo. Before the…before the…the qualifiers…

[Daniel]: This is Luciano Borges, a journalist with the newspaper Folha de São Paulo.

[Luciano]: And I became a little closer to him: he was a friend, we talked all the time. Then I…I think…I saw how famous he was there, in Chile. He was an idol, muito grande.

[Daniel]: Let’s get back to the qualifiers. The expectations were enormous.

[Jorge]: I think there was a kind of…of…of shared madness that fundamentally centered on…on the team, that Chilean National Team, that could defeat Brazil. And that would be historic.

[Daniel]: The first match against Brazil was played in the National Stadium in Santiago on August 13th, 1989.

[Jorge]: And Chile’s match with Brazil here in Santiago was…was violent, there was an incredible amount of hitting…

[Daniel]: From the first moment, we should say: from before the first moment.

[Luciano]: The stadium was packed full.

[Daniel]: Luciano was covering all of the team’s matches.

[Luciano]: FIFA protocol dictates that they…the two teams have to go onto the field together, at the same time.

[Daniel]: To protect both teams from jeers and violence. It’s a rule that makes a lot of sense. But that day Roberto Rojas…

[Luciano]: He entered the pitch and the whole Chilean team followed him, leaving the Brazilian team…alone, so when they came out they were, in Brazil we call them vaiados..

[Daniel]: Vaiados, or boos. The Brazilian National team was booed. That gesture on the part of Rojas, to leave his rival momentarily alone, well that marked the tone of the entire encounter. The fans were furious. So were the players…

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: They’re inciting… What’s going on? Romario was there coming to blows with a few Chilean players. This is frankly unacceptable.

[Jorge Aravena]: It was a very rough game, very rough. There was a lot of hitting….from both sides. From both sides.

[Daniel]: This is Jorge Aravena, known as el Mortero [lit. the mortar] among Chilean fans. He was a midfielder for the national team at the time. And Romario —the Romario—, future FC Barcelona star, future world champion pisó el palito, as we say in Peru. In other words, let them get a rise out of him.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: And now Romario…

[Commentator]: Romario has…

[Presenter]: He hit Hisis. Red: that’s a red card for Romario. What a start to the match, huh?

[Jorge Aravena]: Romario was kicked out of the match after 10 minutes.

[Daniel]: But Romario wouldn’t be the only one to be removed. On the Chilean side…

[Danilo]: There was a brutal kick between Raúl Ormeño and Branco, which got Ormeño a yellow card right off the bat. A that kick could’ve cost him 10 games.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: Ormeño fouls. It’s a yellow card, the first of the match.

[Commentator]: What Ormeño did was very dangerous, the crowd is absolutely right not to like it. Ormeño aimed high up at Branco’s shin, who was getting away.

[Jorge Aravena]: Raúl Ormeño, one of my teammates, was removed from the game after 15 or 20 minutes.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: Ormeño, red card. Red card for Ormeño. We said it: careful, Ormeño.

[Daniel]: At half-time, the Brazilian team had to go past the stand with all of the Chilean fans in order to get to their locker room. And people…

[Luciano]: Threw rocks and things like that. We had to, uh…I was with them, we had to go down the stairs with police protection, with them using their shields.

[Daniel]: That’s how ugly the environment in the stadium was. And at minute the 55 of the match, now in second half…

[Jorge Aravena]: Brazil took the lead with an own goal from Chile…

[Daniel]: But Chile came back with a famous goal, or maybe “notorious” would be the word. The referee signaled a foul by Taffarel, the Brazilian goalkeeper, and Jorge Aravena…

[Jorge Aravena]: I run up to…toward the play and I ask Tafferel for the ball, he passes it to me and I…put it on the ground and pass it to Basay and he scores a goal and we tie.

[Daniel]: In other words, Averena didn’t wait for the Brazilian defense to get in position. It was opportunist, cleaver and some would say dirty goal. But not me. Anyway, it ended with a tie.

This is Oscar Wirth the second goal keeper for the team.

[Óscar Wirth]: For me, uh…uh… that 1-1 is an accurate reflection of a kind of group behavior that isn’t, uh, suitable for facing, let’s say, a rival like… of Brazil’s caliber.

[Daniel]: Luciano Borges found Roberto Rojas after the match. They greeted each other as friends and Luciano asked him a question.

[Luciano]: Why did you go out with the national team first? Why all of that tension? And he said, “It’s the only shot we have. It was a resource we needed to use to put more pressure on Brazil to see if we could win.”

[Daniel]: Because that’s what this is about, right? Winning. But all of violence in the stadium, mainly on the part of fans toward the Brazilian players, had consequences. FIFA sanctioned the Chilean Federation and the punishment was they would have to play the next home game away. In Argentina.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: In the Provincial Malvinas Argentinas Stadium in 16 degree weather (~60 degrees F), with clear skies, the match begins.

[Daniel]: A match against Venezuela, which was —with all due respect to our Venezuelan friends— practically a formality.

Chile won by a landslide. And the re-match in Caracas, too. But Brazil did the same thing—beat Venezuela at home and away, but with more goals

And so, Chile made it to the final match, in Rio de Janeiro, with the obligation to win. Due to the goal difference, a tie would be enough for Brazil. And the chileans had a bad taste in their mouths after having to play that game away and having been sanctioned when Brazil wasn’t. According to Danilo Díaz, the Brazilians deserved it too.

[Danilo]: Because the Brazilian coaching staff, uh, was responsible for the incidents too, because of their provocations, right? There are no white doves here. Everyone was guilty. And there was the sense that there was…a war waging against Chile.

[Daniel]: The hope of winning on merit now felt very distant.

Ok, but before going to Rio for the decisive match, we have to remember the context of Chilean soccer, what we mentioned at the start of this story. Roberto Rojas was part of that soccer culture that lived alongside corruption.

[Danilo]: Roberto Rojas, if you looked at him at the time, was a guy who was involved in big scandals. For example, the scandal involving the falsified passports at the Sudamericano de Paysandú in ’79.

[Daniel]: This is what he’s referring to: several Chileans used fake passports to play in that youth tournament. They had lowered their age to be able to play.

[Danilo]: In other words, the Chilean government issued fake passports so the players could compete in that Sudamericano in Uruguay. And Rojas was there. There were several other too.

[Daniel]: Coaches, trainers and even employees at the Civil Registry went down for this. Several were arrested. In the Chilean media they talked about all this as if the players were victims. Like they’d been tricked. Danilo Díaz says that wasn’t the case.

[Danilo]: By the time you’re 19, you know you’re 19. You know…Or if you’re 22, you know you’re 22 not 19. They weren’t victims. The players knew what this was all about.

[Daniel]: That’s not all. Rojas had also tested positive for doping in June of 1984, which disqualified him from the Olympics in Los Angeles. He alleges that the drug had been injected with the drug for a broken finger, but well…

[Danilo]: Later I remember he hit a doctor at a match. I remember that day at a match with Unión Española…with Colo Colo. He attacked a doctor, Eugenio Valdecanto, on the pitch. That was in ’86. So, you start to look through his trajectory and realize that he was always a guy who, uh, who pushed the limits, who pushed the limits.

[Daniel]: But sometimes the limits are pushed too far.

We’ll be back after the break.

[Ad]: Support for this NPR podcast and the following message come from Sleep Number, offering beds that adjust on each side to your ideal comfort. Their newest beds are so smart, they automatically adjust to keep you and your partner both sleeping comfortably all night. Find out why 9 out of 10 owners recommend it. Visit sleepnumber.com to find a store near you.

[Sam Sanders, host de It’s Been a Minute]: Hey y’all. I’m Sam Sanders, I host an NPR show called It’s Been a Minute. Every Friday on this show I talk out the week of news. Because sometimes the best way to process everything going on right now is through good conversation. Download the show and we’ll process everything together.

[Rachel Martin, co-host de Up First]: Before you can start your day, you like to know what’s happening in the news. That’s what Up First is for. It’s the morning news podcast from NPR. The news you need to take on the day, in just about 10 minutes. Listen to Up First on the NPR One app or wherever you get your podcast.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. And here’s where we left the story. There was one match left to decide who would go to the 1990 World Cup in Italy: Chile or Brazil.

[Juan Carlos]: The definitive match was on us.

[Danilo]: Chile had to win. Brazil could move on with a tie.

[Daniel]: And the environment was tense.

[Jorge Hevia]: How did Chile’s bus arrive at the hotel? Uh, there were, I don’t know, 4, 5, 6 police officers on motorcycles with the team. They arrived at night, with the lights out so no one would know the team was arriving. It was…It was like going to a…It was like preparing for a team that was going into a war zone.

[Jorge Aravena]: Let’s see, we knew we were going to play….in…in…in their stadium, in Rio de Janeiro. With their crowd in the bleachers. The stadium was full, it was the old Maracaná when it could fit a lot of people…

[Daniel]: Rio de Janeiro’s legendary stadium. There were going to be more than 140,000 fans

[Juan Carlos]: Brazil was started to get…to get a little nervous because Chile had won and Chile could eliminate them.

[Luciano]: What left them the most irritated, angry, was that most Brazilians were barely even talking about the match, as if the match was already over, like it was already settled. Like the Brazilians don’t…don’t view the Chileans as a…a threat, like a worthy adversary, that sort of thing.

[Danilo]: And “a cabecear las piedras” [slam our heads against the rocks] is what they said, the players. “That day we’re going to go out there and cabecear las piedras at Maracaná”.

[Daniel]: “A cabecear piedras”, in other words, try to do the impossible.

[Juan Carlos]: And we were ready to say that if something happened in Brazil, if we weren’t safe, we weren’t going to play there.

[Danilo]: They left Santiago planning to withdraw from the game and file a complaint…at the first incident that might occur, whatever it was.

[Daniel]: In other words, they would do what they needed to suspend the match. For them to play at a neutral stadium; without 140,000 Brazilian fans cheering on their team. It was an extension of the logic that prevailed in soccer at the time: win at all costs. This is Óscar Wirth.

[Óscar]: A phrase that, I…I’m telling you made me…it really bothers me. I heard it many times, many. And…and…it really bothered me, I mean, hearing that phrase: “We have to win at all costs.”

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: Attention in Santiago. The Brazilian team is playing. The game has started…

[Jorge Aravena]: We knew that, uh, that it wasn’t going to be an easy or comfortable match. And we weren’t planning on making it easy or comfortable for them either.

[Daniel]: Hugo González, a defender for the national team, remembers it like this.

[Hugo González]: Well, it was a very imposing Brazil, trying to…to secure their win. They were on us… uh, it was really hard for us to advance.

[Danilo]: Chile barely crossed the middle of the pitch in the first half.

[Hugo]: And we…we were trying to…to…to take the pressure…that Brazil was putting on us, and trying to move forward, obviously, in a counter attack…to get lucky and score.

[Danilo]: And that day Roberto Rojas made some saves that were amazing.

[Luciano]: And Rojas was playing really well. Really well.

[Jorge Hevia]: Chile wasn’t doing very well and Roberto Rojas was the star of the game: he made some incredible saves. He… did some brutal stuff: a shot from Branco, I remember, at an angle and…he caught with such elasticity. The guy played a hell of a match.

[Daniel]: The team’s trainer at the time was Orlando Aravena, but he wasn’t able to be on the bench for that match. He had been sanctioned for what had happened at the match in Santiago.

[Milton Millas]: Orlando Aravena had been sanctioned.

[Daniel]: This is Milton Millas, who narrated the match for channel 13 in Chile.

[Milton Millas]: So I offered to let him go to my box to get a good view of the match, protected from the public…

[Daniel]: But on top of that, Milton Millas gave him a walkie-talkie so the trainer could communicate with the bench. This detail will be important later on.

[Milton]: So, I had the advantage of having the instructions the trainer was giving air on channel 13 first…

[Danilo]: The first half was 0-0 and Brazil could have been up by 3 or 4 goals. 3 or 4 goals. But Roberto Rojas blocked them.

[Daniel]: You’re telling me that at halftime…the feeling among…among the Chilean National Team was “we’re not going to win fairly, we have to win some other way”

[Óscar]: No, I wouldn’t say it like that, but…well, deep down, that’s what was meant.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: The match has resumed, dear viewers, here in Maracaná. Chile and Brazil are tied 0-0. There’s no change.

[Danilo]: And Rojas held up in the second half, until the goal from…from…Careca…

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: Careca gets ready. Careca, Careca and Roberto Rojas. And Roberto Rojas couldn’t get it. Careca sends the crowd into a frenzy. They’re going wild.

[Danilo]: A left kick which he didn’t execute very well, and I think Rojas could have done more. With that, Brazil was qualifying.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: Four minutes into the second half, Careca has the advantage at 1-0. Brazil starts to celebrate.

[Daniel]: But that match wouldn’t go down in history because of Careca’s goal, or Rojas’ saves, but because of something else. Something that happened in Chile’s defensive zone, but while the ball was on the other end of the field.

[Luciano]: I was at a press stand watching the match. At one point, a…a colleague from Folha de Sao Paulo, Fernando Santos, uh, got my attention and said: “Look, look at the firework.”

[Jorge Avarena]: I saw the flare, it shot out smoking.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: And now? Let’s see, what’s happening?

[Hugo]: I turn to see…to see Roberto there. Right next to him there had been a…a flash where a… I had no idea what it was at the time.

[Luciano]: The fans had made that sound that you make when there’s a good opportunity to score a goal but it doesn’t happen: “Ooooo!”

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: They shot a…a…a flare. The goalkeeper, Roberto Rojas has been injured.

[Jorge Aravena]: And I see it fall and I see Roberto fall. I said: “Oh, it hit him.”

[Juan Carlos]: We saw Roberto get hit and we didn’t see him bleed. Really: we didn’t see him bleed. Roberto, when…when he goes back, he’s bleeding.

[Jorge Hevia]: When…When the event occurred, I had to start to describe a situation that we…that we had all seen from a distance.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: Unfortunate. Ah, this is in…the southern goal of what would be the National Stadium. They’re calling aides. It’s a kind of firecracker with a flare. Roberto Rojas seems to be in very bad condition.

[Daniel]: You saw the flare fall?

[Óscar]: Perfectly. Yes, well, at the time…Now…Now my vision fails me a little, but and that time I can assure you my vision was fine.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: We’re hoping…it wasn’t anything special or anything serious. But…but the entire Chilean team is gathered around him.

[Óscar]: I remember perfectly how my teammates were upset by what they had seen, and I told them: “Stay calm because the flare actually fell about 2 or 3 meters behind him.” I told them: “Don’t worry.”

[Daniel]:But it was already too late for that: all of the players were upset; Rojas was stretched out on the ground, bleeding from his left eyebrow, where supposedly he had been hit by the flare; a cloud of smoke covered everyone and no one in the stadium really knew what was going on.

[Juan Carlos]: And that’s when I put my hands up and we all put our hands up to…to…to call over the people who were going to take of him. A ref comes and then the Brazilian players, then…by this point it’s becoming a…a…now a pretty chaotic situation, because we saw how he was bleeding, because he was bleeding, that’s true, there was blood, we had…we had to do something right away on the medical side of things.

[Luciano]: Then the Chileans started to…to riot on the field. The players wouldn’t let the engage near Rojas. They put him on a stretcher and they took Rojas to the locker room.

[Daniel]: According to other accounts, the match officials wouldn’t let the stretcher on the field, so the Chilean players carried Rojas themselves. And as they left the field, they asked the press to record the scene, to see the blood.

Now we need to introduce a new character to the story: Paulo Teixeira.

[Paulo Teixeira]: I have been a soccer photographer for 15 years, uh, for four World Cups and numerous matches in South America and all over the world. So, well, my eyes have seen a lot.

[Daniel]: He now lives in Portugal and works as an agent: he represents soccer players. He was on the sideline the night of that match, taking photos.

[Paulo]: There’s this rule in photography: If you see what’s happening, you aren’t photographing, ok? And I saw it, that, I mean…the flying object, from the stands of the right side of Maracaná, shooting out, arching and…and…and falling toward the ground. But since I saw it, I didn’t photograph it.

[Daniel]: Next to him was the Argentine photographer Ricardo Alfieri.

[Paulo]: We start to…to…to talk among ourselves. I asked Ricardo: “Ricardo, what about you?” He told me “I got five shots.”

[Daniel]: And it’s no exaggeration to say that, in that moment, those five shots were the more important images in all of South America.

We’ll come back to the story of those photos, but first: the pitch was in chaos. The score was 1-0 with Brazil ahead. And the Chilean team had taken Rojas to the locker room.

And those players made a decision that would have important consequences. Not just for them, but for all of Chilean soccer.

[Juan Carlos]: Adrenaline leads you all of a sudden, maybe, to say a lot of things.

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Jorge Hevia presenting]: What has happened is very serious. They didn’t just take him to the locker room, but the whole team went. What…what’s going to happen?

[Juan Carlos]: What the f**k, how could they do that? No, we have to file a complaint, this can’t happen, Brazil needs to be disqualified.

[Daniel]: From the broadcast booth, Orlando Aravena received news from the president of the Chilean Football Federation, Sergio Stoppel.

[Milton]: “Orlando —he says—, Orlando: we’re withdrawing the team.” Orlando looks at me, lowers his… his walkie talkie, and says to me: “We’re f***d if we pull the team.”

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: You get the feeling Chile isn’t coming back, huh?

[Journalist]: I agree, Pedro. Some commentators down there have said that Chile will not return to the field.

[Milton]: They suspend the game. Chile withdraws.

[Daniel]: According to Danilo Díaz, two federation officials begged Stoppel not to withdraw.

[Danilo]: “Talk to the players, tell the team to get back out there. This is a lost cause, but the sanctions will be very serious, they could leave us out of the next World Cup.”

[Daniel]: But the decision was made. The Chilean National Team was holed up in their locker room, all very worried about Rojas.

[Juan Carlos]: And they took him to a room, a part of the locker room where they gave massages, and they were taking care of him there.

[Daniel]: Jorge Hevia went down to the locker room. As part of the official broadcast, he thought they would let him in, but they didn’t. So he stayed out. But while he waited, he did find one of the most important figures in international soccer.

[Jorge Hevia]: And I’m there with the great Edson Arantes do Nascimento, Pele: “Pele, what do you think about everything that’s happened?”. And he says to me: “That’s Metapio.” I’ll never forget what he said: “That’s Metapio. That’s fake. It’s not real.”

[Daniel]: Metapio is a medication used to disinfect wounds. A lot of times it’s red. In other words, Pele was suggesting that the blood on Rojas wasn’t real.

[Juan Carlos]: We were in the part of the locker room where we got dressed. Everyone was talking about it, of course, we were saying: “S**t…what happened.” But no one doubted it.

[Luciano]: I was worried about Rojas.

[Milton]: I got past Orlando Aravena’s security so that the police could let me in.

[Luciano]: They let me in for…for a few seconds. I saw Rojas, sitting on a bench with the doctor, and saw that it was a cut.

[Milton]: When I went into Chile’s locker room, it smelled like blood. They showed me Roberto Rojas, who had a few cuts.

[Luciano]: I remember….thinking: “How can a flare…make a cut?” There was no, uh, burn.

[Daniel]: Carlos Caszely was a forward for the national team for more than 15 years, he had retired not long before and was very popular among the fans. He was in Maracaná that night, and gave an interview moments after the team withdrew from the match.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Carlos Caszely]: Well, according to the medical report, once the flare passed over Roberto a tail attached to the firework hit him producing a cut on his eyebrow and that was what they treated him for. Now we’re going to see what Roberto really has.

[Daniel]: At the time they didn’t know for sure. But what was clear was that the team wasn’t going back on the field. And with that…

(SOUNDBITE FROM VIDEO OF THE MATCH)

[Presenter]: It’s over…

[Commentator]: And the game is effectively over.

[Daniel]: From the point of view of the Brazilians, there was an important problem.

[Milton]: Terra Teixeira, the president of Brazilian Football, came up to me, heated, and says: “Milton, what happened is very serious.”

[Paulo]: That’s when we found out that TV Globo, who had exclusive rights to the…the…footage…of the game, with 16 cameras on the field, didn’t get the shot.

[Daniel]: In other words, it wasn’t completely clear what happened. There was no evidence. Everyone saw the flare fall. Everyone saw Rojas fall. He was injured. The Chileans believed him blindingly, but the Brazilian press didn’t: what had really happened?

The stakes were high. If it was proven that the flare had hit Rojas, Brazil could be sanctioned. And could even lose their spot at the World Cup. But if he was faking, it would be just as bad for the Chileans.

But there was one person who could make it all clear.

[Paulo]: The only one, as luck would have it… Remember there were about 130,000 people at Maracaná, there was one guy how had the shot. And that guy was my friend and he was standing next to me.

[Daniel]: It was Ricardo Alfieri, the photographer. This is audio of him recorded that same night.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Ricardo Alfieri]: No, what I saw was that the…the flare fell and it did not hit him. No, no, no.

[Journalist]: Would it be possible to see that in those photos?

[Ricardo]: Yes, well, I’m working for Soccer Magazine, a Japanese magazine, and I’m sure they will publish them because it is very important documentation, right?

[Daniel]: But Paulo Teixeira had other plans for those photos.

[Paulo]: So I told Ricardo: “Ricardo, listen, let me… I’ll handle this. Forget about Japan, right now you’re in Brazil. Your…your…your flight is tomorrow morning, we’re going to handle this from now on commercially, ok?

[Daniel]: That’s when Paulo stopped being a photographer and became an agent. The images Ricardo had in his hands were extremely valuable. Rede Globo and Rede Manchete, two rather large media companies in Brazil, wanted exclusive rights to the photos. Rede Manchete offered to take Teixeira to their own studio to develop the film. And some representatives from Rede Globo followed their car, just in case.

[Paulo]: For four hours I was living… like a king, because they immediately put us in a limo to take me and the film to Manchete, uh, TV Machete. It was Sunday, at 8 or 9 at night. They had to get the girl who took care of the lab from her house at 10 at night to get her in the lab to turn on the heat because the photos could only be developed at 38.5°C [101.3°F]. She was furious. Imagine. It takes three hours to develop these photos…

[Daniel]: Teixeira asked for $5,000 for the photos.

[Paulo]: For us that was a fortune. We’re talking about nearly 30 years ago.

[Daniel]: Rede Manchete said no, they weren’t going to offer them $5,000. So Teixeira offered them to Rede Globo. And they said yes.

[Paulo]: I was satisfied, Ricardo was satisfied, la Globo…Globo was satisfied, the only ones who were, uh, “pelando bola” —as they say— were Manchete.

[Daniel]: Teixeira made copies of the negatives. He gave the originals to Alfieri and the next day, at 10 in the morning, he brought the five photos to Rede Global. They gave him $5,000 right there. He gave 60% to Alfieri and he kept the other 40%.

The night after the match, they published the photos.

In Jornal Nacional from Rede Globo, a half-hour story…

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: Only Alfieri caught the exact moment the flare fell at Maracaná. You’re going to see the exclusive now.

[Paulo]: They dedicated 15 minutes to this. And it shocked everyone.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: In the first photo, the goalkeeper, Rojas, is standing and a flare falls to his left at a distance of more than a meter, more or less.

[Daniel]: The photos clearly showed the flare falling behind el Cóndor Rojas. It didn’t touch him. It was the proof Brazil needed. Whatever wound the Chilean goalie had suffered wasn’t from the flare.

The president of the Brazilian Association would take video of the news to Zurich, where the FIFA headquarters were located, and with that evidence he would keep Brazil from being disqualified.

[Paulo]: The curious thing is that 48 hours after the situation, after the fact, I got a…call from someone from Chile offering me $200,000 to make the photos disappear.

[Daniel]: Two hundred thousand dollars: equal to $400,000 today. Imagine it. It was already very late but, of course, in 1989 news didn’t spread like they do now.

And besides, Paulo assures me he never would have sold them and doing-so risk keeping his country out of the World Cup.

The night of the match, no one in the Chilean locker room knew about Alfieri’s photos. They just knew that they had to go back to Santiago with a lot of uncertainty. And Rojas…

[Juan Carlos]: They brought him up on a stretcher. I don’t remember if it as a stretcher or a chair, but I remember…more than anything that they…they put him in a special place where the doctors were and he was cared for there.

[Danilo]: People went to the airport at 4 or 5 in the morning to welcome the team.

[Luciano]: I remember the Chilean National Team went back to Chile like soldiers coming back from war and came out…vi…vi…victorious. Rojas’ popularity was through the roof.

[Daniel]: For a lot of Chileans, there was no doubt what had happened. Rojas was a martyr for the country. According to reports at the time, 3,000 people gathered spontaneously in front of the Brazilian Embassy in Santiago to protest. They threw rocks, broke windows and burned a Brazilian flag –and the police did nothing.

[Danilo]: I remember they hit an American basketball player, Willy Wittenberg, because he was passing through the area, and they said—since he’s black—: “oh, he’s Brazilian.” And they hit him!

[Daniel]: They chanted: “Condor, our friend, the people are with you!”

[Danilo]: The newspaper, the radio…the radio stations, TV, all created such a brutal climate that in the end, Roberto Rojas’ cause turned into a national cause.

[Daniel]: A few days after landing in Santiago, Roberto Rojas gave an interview on a show called Zoom Deportivo. He appeared with a bandage on his forehead.

(SOUNDBITE FROM A TELEVISION PROGRAM)

[Pedro Carcuro]: Roberto, uh, a visual note: You look very gaunt, you look thinner than when we were together at the qualifiers for the World Cup.

[Roberto Rojas]: No, no, it’s true. This makeup even hides a lot of things that really have happened to me these past few days.

[Daniel]: It was a cautious, respectful interview.

(SOUNDBITE FROM A TELEVISION PROGRAM)

[Pedro]: Are you calm at the moment?

[Roberto]: At the moment…

[Pedro]: Or are you upset?

[Roberto]: Uh, no, no, I’m calm now. I think four of five days ago, when I gave that press conference, I expressed what I really, with my family, was going through so…

[Daniel]: They treated him very delicately, like the hero he was at that moment. But…

[Danilo]: There were several journalists who said: “How could you he a cut? How can he get cut by a flare? He should’ve been burned, not cut.” There were things that…that…that made such simple basic sense.

[Daniel]: In Brazil, Alfieri’s photos had already been published and the story they told was clear: the flare didn’t touch him. Rojas had cut himself. On purpose.

Milton Millas was one of the first to ask Rojas directly what had happened.

[Milton]: I said: “Roberto, tell me the truth.” “No” —he said— “Milton. It’s absolutely how you saw it.”

[Daniel]: How you saw in the stadium and on TV but not in the photos, of course.

The evidence was piling up. On September 10th, a week after the match, FIFA sanctioned Chile for having left the pitch, which sent Brazil automatically to the World Cup. At the same time they launched an investigation into Roberto Rojas and Aravena’s team. In late October, 1898, FIFA’s Disciplinary Commission gave its verdict in Zurich.

Milton Millas saw el Cóndor right before.

[Milton]: And when Roberto Rojas comes to hear the decision, I ask him, “How are you?” “I’m gonna block a penalty,” he said.

[Daniel]: “I’m going to block a penalty.”

[Milton]: After he came out he was punished for life.

[Daniel]: Roberto Rojas never played another professional match. His last performance as a competitive goalkeeper was that day, September 13th, 1989, at Maracaná. The exact phrasing of the ruling was: “Rojas is suspended for life for having feigned an injury.” It was alleged that Rojas had cut himself with a scalpel.

The president of the Federation, Sergio Stoppel, was also sanctioned for life. And Fernando Astengo, the vice-captain of the national team, the one who withdrew the team, received a 5 year sanction.

But perhaps most painful was the team’s punishment: FIFA decided that Chile could not participate in the next World Cup: United States 1994. A World Cup, I should say, that Brazil won.

It wasn’t until May of 1990, 8 months after the incident at Maracaná, that Roberto Rojas finally confessed. On the cover of the newspaper La Tercera, a picture of el Cóndor was published with two words: “I’m guilty.”

And he went on TV and confessed.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Roberto]: So we got it in our heads that we were going to get the result we wanted, at all costs. At all costs, I mean, from an error…We talked about it once and that’s all. It wasn’t even analyzed in detail. No. It was just there, bouncing around in hour heads, as we say.

Well, I put it in my sock, I went onto the field with it, but…I went on the field with that instrument, but I wasn’t worried about what I had to do with it. In the first half I forgot about it. If you remember I was playing one of the best matches of my life in the first half…at that…at that time. And then that was when I say to myself: Something had to be steering me internally to…at that moment, in a matter of seconds, lead me to wanting to do something that was impossible to do.

And that object fell, and I remember that I…the ball was in front of me in the other area, Taffarel had it, I think, and the ball was flying through the air and at that moment I feel a big commotion behind my goal. I turn my head left and I see a light falling but there was a lot of smoke and…And that was when, in a manner of seconds, I said: “Well, here it is.” But it was milliseconds. Maybe if I had thought about it for a minute, maybe the object would have fallen to the ground and I wouldn’t have done anything. Then, in that moment, I got involved in something, making everyone think that it really had happened.

[Jorge Aravena]: The truth is that until Roberto said that he had injured himself, until that moment, I believed what he had said. I honestly believed him.

[Luciano]: I remember he told me: “I felt much lighter, much lighter after…after…I told the truth.”

In Chile everyone went to his defense, and he knew he was guilty. There was a very heavy weight that went with that.

[Daniel]: This is Óscar Wirth.

[Óscar]: I have no idea, what was…how…how…how they set this all up. But they did set it up, that’s clear, you know?

[Daniel]: They is plural. You didn’t say “he set it up.”

[Óscar]: Yes, of course.

[Daniel]: Rather “they set it up.”

[Óscar]: These things aren’t about one person. In a team sport, these things aren’t about just one person…they involve…they involve several people. I don’t know if it was 5, 10, everyone…Or 2 or 3 people, but…but it was…it was more than one.

[Danilo]: I think there were players who knew. The ones who were closest to him. Who gave him the scalpel? How did they get the scalpel in his glove? He couldn’t have done it alone.

[Daniel]: But it was never revealed who else on the team or the support staff could have known about the plan. There are a lot of theories but little proof.

The first soccer player I met with when I went to Chile was Jorge Aravena. We’ve heard him throughout this story. He was an important player on Rojas’ team.

I went to find him on the training fields around Colo Colo’s stadium. It was a beautiful Spring day, in August of last year; a perfect day to play soccer. And that’s just what Aravena came to do.

I’m not Chilean, so I didn’t grow up seeing that team play, or admiring the players from Rojas’ generation. In other word, for me, Aravena wasn’t a legend, he wasn’t el Mortero. He was just a man who loved soccer. I saw him get ready to play with the same enthusiasm I feel on Saturday morning, or that my son feels before a match. I was impressed that after he told me about what happened with Rojas, he didn’t feel any resentment. Not against his teammate, or soccer, which in the end is still makes him happy.

[Jorge Aravena]: Playing it the most beautiful thing in the world. Think about it: Now I’m 59 years old, I get together with a group of friends every Monday to play. The vast majority of us have flimsy ankles and we come to play all the same. We all hurt a lot because we all have a lot of injuries. But we come to play because we like to play. Playing was the most beautiful part.

[Daniel]: We agree on that —me, Chilean fans, Brazilian fans, millions of fans of the game around the world. The irony in all this, maybe, is that in part the Chileans were right.

I mean, I’m not justifying what Roberto Rojas did at all, but think about it: the Chilean team assumed they couldn’t win playing fairly, that the corrupt FIFA would not have allowed it. Well, the corruption at FIFA, at that time, was a suspicion; now it’s a fact.

In 2015 what some called “FIFA Gate” was uncovered, which ended with more than 40 people accused of bribery, fraud, and money laundering, and with the resignation of then FIFA president, Joseph Blatter.

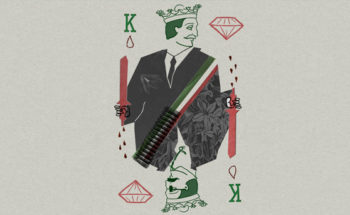

And well, if some have branded Batter as the prince of corruption at FIFA, his predecessor, Joao Havelange –president when el Cóndor was sanctioned– well, Havelange was the king.

In other words: yes, playing can be beautiful, but there are always those who damage the sport we love so much.

(SOUNDBITE FROM TELEPHONE CALL)

[Mujer]: Hello?

[Daniel]: Hello, good afternoon. Can I speak with Roberto Rojas, please…

I called Roberto Rojas to get his perspective on all of this but he didn’t want to speak. His wife told me that Roberto is a man who prefers to look toward the future. A position I understand, obviously. I even respect it.

So, what can be said about Rojas today?

He lives in Brazil and for several years after his sanctioning he was a goalie trainer with his old club, São Paulo. In 2013, after getting sick, the club Colo Colo organized a charity match in Santiago to help with his medical bills. If you watch the videos of that match, it’s clear that the fans and the players still really care about him.

And in Chile, when you talk about the best goalkeepers they’ve had, they always remember el Cóndor.

This story was produced by me with the help of an extraordinary team. Without the effort and talent of Silvia Viñas, nothing would happen. The same goes for Luis Fernando Vargas and David Trujillo, who helped to transcribe and organize hours and hours of audio. Silvia and Camila are the editors, a couple of rock-stars. Sound design is by Andrés Azpiri. The fact checking is by Ana Prieto and Cristobal Correa.

This story was produced in collaboration with 30 for 30, Treinta por treinta in Spanish. It’s an ESPN podcast. If you haven’t listened to it, it’s really worth it. They have a new season that just came out about the yoga cult in the US and it’s incredible. We have a link on our website. Special thanks to Jody Avirgan and Adam Neuhaus. Keep an eye out for a version of the story about el Cóndor in English. When it comes out, we’ll let you know.

Thanks to Paolo Rascao, Geredo Rodríguez and Giancarlo Aracena. Thanks to our friends from the magazine De Cabeza in Santiago. If you don’t know about De Cabeza, I really recommend it. They publish excellent stories about Latin American soccer. We also have a link to them on our web page.

The World Cup is right around the corner and we want to play a game with you to make the wait fun. It’s going to be called “El mundialito Radio Ambulante.” Stayed tuned to our social network accounts (Twitter, Whatsapp and the Podcast Club on Facebook) to learn about how to participate. We will send a Radio Ambulante t-shirt and stickers to the winner.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Jorge Caraballo, Patrick Moseley, Barbara Sawhill, Luis Trelles and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

To hear more episodes and learn more about this story, visit our web page: radioambulante.org. Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.