Translation – The Room That Was A Brain

Share:

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

The story we’re telling today took place more than 40 years ago.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: Now the story that I want to tell you began in 1971 in the middle of the year.

[Daniel]: And this is one of its protagonists: an Englishman named Stafford Beer. The audio you just heard is him, speaking at a conference at the University of Manchester in 1974. When Beer died in 2002, the media described him as a visionary and a guru, a “mix between Orson Welles and Socrates.”

Beer studied philosophy, mathematics, and psychology. He didn’t finish any of those degrees, but he spent his time thinking about how to revolutionize technology. His ideas, well, some are not so easy to explain. Like, biological computers. Does that sound like anything to you? No? Well, me either. But it was one of Beer’s ideas.

He was obsessed with computing and automation: automated factories, with no humans, things that at the time sounded like science fiction but that now aren’t so different from reality. However, reading Beer is a trip. His texts are more like Jules Verne’s than any of the information science manuals we have today.

So, as Beer himself said in that conference, today’s story starts a few years earlier, in 1971, when one day, out of nowhere…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: I suddenly got a letter which very much changed my life.

[Daniel]: And that letter which would change his life, came from the other side of the world, from Chile. And in that letter, the Chilean government made him an offer, for him to Chile to work on a project that would put into practice his particular areas of expertise: organizing the Chilean economy.

In the late ‘50s, Beer had invented something he called “management cybernetics” or “control science,” which basically means using principles of biology, mathematics, and information science to run any company.

I know, this may sound really confusing, but be patient and later this will make more sense.

Those ideas of Beer’s —about “management cybernetics”— became popular and he started working as a consultant at big companies. He got rich: he drove a Rolls Royce and had an enormous house in the London suburbs.

And now he was getting this offer: apply what he had been doing at some companies to the entire Chilean economy. The goal of the project was to revolutionize how Chile worked.

And let’s remember the context. A few months earlier, in October 1970…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Voice]: The Congress declares Salvador Allende Gossens president of the Republic. This session is adjourned.

[Daniel]: For the first time, a socialist candidate had been declared president in Chile. This is Allende at a speech the day of the election.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Salvador Allende]: We are the legitimate heirs of the fathers of the country, and together we will achieve the second independence: the economic independence of Chile.

[Daniel]: Allende had promised that the people would take part in the country’s decisions, that there was going to be economic, political, cultural, and social change. They were beginning a revolution that needed new ways of thinking, of organizing. So that’s why they got in touch with Beer.

Beer accepted and a few months later, he traveled to the other side of the world to present his proposal to Allende and his team.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: Let me tell you what happened when I first explained it to President Allende himself.

[Daniel]: Again, this is Beer at a conference, relating what happened when he brought his proposal to Allende.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: Allende was a doctor, a medical doctor as you may know. And, therefore, it was very easy to explain the model to him in terms of neuro cybernetics as the way of controlling the body.

[Daniel]: He says that since Allende was a doctor, in order to explain what he wanted to do with the Chilean economy, he made an analogy to the body.

The idea was to connect the country —industry, the cabinet secretaries, everything— through a network —a network that would function like the body’s nervous system— and that it would collect information from every factory in Chile, from the north to south, to help monitor day-to-day economic activity: how much copper had been mined, what raw materials were needed for industry, etcetera.

Then, all of that information would go to a room, which was like the system’s brain and —from there— they would make decisions —in real-time— about the changes they should make: from closing a factory that wasn’t performing, to doing a public inquiry on an important economic issue.

And when Beer explained to Allende what that brain, that center of operations, would be…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: I drew a big histrionic breath… I was going to say: “This compañero Presidente is you”.

[Daniel]: That is, he was going to say that the brain would be him, Allende. But…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: Before I could say it, he suddenly smiled very broadly and he said: “Ah, at last, the people”.

[Daniel]: In those moments, before Beer could say that, Allende smiled and said: “At last, the people.” In other words, it was clear to Allende that whoever was in that room would be the people. And that was the most important part of Beer’s proposal.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: That was a pretty powerful thing to happen. It had a very big influence on me.

[Daniel]: According to Beer, that was very inspiring for him.

Beer called the project Cybersyn and experts now consider it a predecessor to the internet, but a socialist version, because not only did it connect people in real-time —which is what the internet does— but it was also going to serve the Allende government’s purposes, the ones he had promised on the campaign trail: the people were going to participate in making decisions.

If everything went well, the Cybersyn wasn’t just going to change the history of Chile, but also the way we live with technology now.

Natalia Messer, a Chilean journalist, brings us this story.

[Natalia Messer]: That letter that Beer received in the summer of 1970 was written by three people. One of them was him…

[Raúl Espejo]: Look, my name is Raúl Espejo. I’m originally from Bolivia.

[Natalia]: But when he was a baby, his family moved to Chile, and Raúl grew up in Santiago. Raúl would become the Cybersyn’s technical director, but before that, he studied industrial civil engineering at the Catholic University of Chile and that was where he learned about Beer’s ideas, specifically from one of his books: Decision and Control.

[Raúl]: This book had already been going around in a group inside the engineering school at the Catholic and that group was adapting to all that language.

[Natalia]: In other words, they were already becoming familiar with the language of organization cybernetics. Familiar with that way of looking at a company or factory as a living organism, that regulates itself on its own and can adapt to its environment.

In 1969 —one year after getting his degree— Raúl started working at the government agency in charge of running state-owned companies. It’s called the Corporation for the Fomentation and Production of Chile —known as CORFO— and it would become key after Allende’s victory when in 1971, the government made a critical decision.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Voice]: We are gathered in the grand dining hall of the Palacio de la Moneda, where the president of the Republic, Salvador Allende Gossens, must proceed in a few minutes to sign the decree enacting the constitutional reform that permits the nationalization of the copper industry.

[Natalia]: The complete nationalization of the copper industry, in other words, now the state would be the only entity responsible for mining that mineral. That same year, the Allende government did the same thing with other industries, like banking.

Then, from CORFO, they started to think about what was the best way for the State to manage these new companies. One of the options was a centralized hierarchical, vertical, centralized model, with the president as the highest authority. But that isn’t what Allende had promised in his campaign, so they tossed that aside almost immediately.

And that was one Raúl and other remembered Beer’s ideas, organizational cybernetics.

[Raúl]: Which helped up think not in terms of centralization, but in diffuse terms, in terms of increasing the capacity for coordination without any one person determining what coordination might be necessary.

[Natalia]: In other words, how to organize state-owned companies without Allende having to give all the orders. Beer’s idea was to create communication networks between companies that helped people cooperate rather than compete, to have autonomy without a leader to rule over everyone else. So, with Beer’s ideas in mind, they invited him to Chile.

Raul says that when Beer arrived in Chile…

[Raúl]: He was absolutely fascinated. He really thought that this was like a dream, something he had never considered in his wildest dreams.

[Natalia]: And they, of course, were more than happy.

[Raúl]: To us it was much more exciting than for everyone else (laughs.) Because going in and working with the guru of… of what we could call organizational cybernetics at the global level was a fantastic gift.

[Natalia]: They got to work right away.

[Raúl]: We spent a week talking about everything his ideas meant, and he clarified things, helped us understand. And I don’t think that man slept at all for all those weeks because during the day we were talking, and at night he was producing documents.

[Natalia]: Documents that started to define what Cybersyn was going to be and how they were going to make it a reality.

[Raúl]: What did the project mean? What was it going to do? And there were established… he established four fundamental areas to work on for the project.

[Natalia]: Four areas that would need new ways of thinking and solving problems.

OK, first: for Cybersyn to work, it needed to have real-time information about what was happening at each factory, at each government agency. This was essential because, for Beer, making decisions about the economy with data that had been gathered months earlier —which was what normally happened— was like trying to drive a car looking through the rearview mirror.

So they needed some way of connecting the whole country, to be able to gather that information. And honestly, they didn’t have much in terms of resources. Communication networks like ARPANET —the network that was developed in the US in the late ‘60s and would later become the internet in the ‘80s— had just started working.

And besides, since Allende had assumed the presidency, the US had put an economic blockade in place against Chile because of the socialist ideas the government was promoting. So it was impossible to try to import that technology. But they had a stroke of luck.

[Raúl]: We found 500 telex machines in the National Telecommunications Company’s warehouses which the previous government had bought. No one knew what they were going to be used for.

[Natalia]: They were there, all those telex machines, in a pile. An old piece of technology. And, well, maybe now you don’t know what a telex is. They were very expensive machines, so they never made it into homes. But at big companies, in banks and government offices, they were used to send messages and documents instantaneously. It was the missing link between the telegraph and the fax. If you see one, it looks like a huge typewriter with a telephone attached. And those telex machines were just what they needed.

[Raúl]: That telex network is precisely what allowed for the transformation of that post office world, of sending letters by mail, into a world of easy, simple, immediate communication between people in different organizations.

[Natalia]: We already said that a telex was like a typewriter, and that’s how it worked: you typed on one telex and it transmitted a message to another and the second machine started typing. That’s how they were able to transmit documents from one machine to another.

So, they distributed those 500 telex machines to all the state-owned factories and…

[Raúl]: Well, there we were: ready. And that helped us set up a whole communication network at a national level, from Arica to Punta Arenas.

[Natalia]: From one end of Chile to the other. They called that network Cybernet.

With the telex machines and Cybernet, they had figured out how to receive the information they needed in real-time, but they needed to process all the data that was going to come in.

[Carlos Senna Figueiredo]: Material supplies, production, employee attendance, financial indicators.

[Natalia]: This is…

[Carlos]: My name is Carlos Senna Figueiredo. I’m Brazilian. I’m an engineer and my connection to the project is the result of a number of coincidences.

[Natalia]: Carlos worked on the second component of the project. Cyberstride, the program that was going to automate data analysis.

The coincidences Carlos mentioned that lead him to Cybersyn started in 1969 when he traveled to England to testify before Amnesty International about human rights violations by the military dictatorship that was in Brazil at the time. But just as he was flying to London, the Brazilian military learned about his plan, so…

[Carlos]: I couldn’t go back.

[Natalia]: Because he knew that would mean prison or worse. So, he was stranded.

[Carlos]: Since I was in England, I had to do something to justify my residency. I went to college.

[Natalia]: In Brazil, Carlos worked as an electrical engineer, but…

[Carlos]: I was stuck there, in England, studying math, researching operations and applied mathematics.

[Natalia]: When he graduated, one of his teachers suggested that he go meet Stafford Beer. Carlos had already heard of him and admired his work. According to his teacher, Beer was starting a project in Latin America, so he put them in touch.

[Carlos]: Stafford sent me a short letter saying that he would meet me at the place of his choosing in London.

[Natalia]: A very exclusive club called the Athenaeum.

[Carlos]: And Stafford was there, unmistakable, right? With his… his looking like someone out of the Old Testament, with that kind of beard, full of smoke because he smoked cigars like a demon and the table had a… a glass of whiskey and papers and papers.

[Natalia]: They got to talking and Beer told him about Cybersyn, Chile, and Allende’s plan to organize the country’s economy. Carlos was amazed. He wanted to know more details. After that first meeting, they agreed to see each other again, and Beer invited him to eat dinner at his house, that mansion in the London suburbs.

[Carlos]: His house was like Captain Nemo’s submarine because you went in, clapped your hands like this, and the lights turned on. If you clapped your hands three times, a fountain started running, a fountain. It was like a magical environment he lived in.

[Natalia]: And there, at that dinner, Beer said what Carlos had been waiting for: he offered him the opportunity to be part of Cybersyn. Carlos accepted without hesitation and moved with his wife and two children to Chile, toward the beginning of 1973, when the project was rather far along.

[Carlos]: And I incorporated myself into the project as a specialist in applied mathematics models… mathematical models.

[Natalia]: The idea behind Cyberstride, the program Carlos worked on, was —as Beer had told Allende— that…

[Carlos]: It has to be a more or less living system. In other words, one that resembles a living organism. Even… In even other words, one that adapts by way of levels of autonomy.

[Natalia]: That meant that…

[Carlos]: There can’t be a boss that controls all the variables, all of the units, all of the departments. Its administration has to be autonomous. Like in a human body, Stafford would say. Right now, I’m talking to you. I’m not controlling my heartbeat or the rhythm of my breath. And my foot. It doesn’t even occur to me that I have a foot.

[Natalia]: You don’t control it consciously. But, if there is a problem, for example, if someone comes over and steps on your foot…

[Carlos]: Then there is a signal saying: “Look, something is wrong with my foot.” That was the system. That was the idea.

[Natalia]: Cyberstride would send that alert. It received all the information from Cybernet —the telex network we already mentioned— and then Cyberstride analyzed the data and made short-term predictions: if the program calculated that copper, for instance, was going to be behind, it sent an automatic alert to the factory.

[Carlos]: In other words, the factories were supposed to operate autonomously without the head of the industrial branch or even CORFO knowing. As long as it’s normal, let it operate.

[Natalia]: But, if after getting the alert at the factory, they weren’t able to solve the problem…

[Carlos]: Then a signal goes out and goes to the next, higher, external administrative level. If it’s solved, great, if not, that signal goes out again, like in a human body, in which a signal that something is going awry, it comes to my conscious attention.

[Natalia]: That was how the project was going to give freedom and autonomy to different levels of production: it only got the attention of the higher level when it was necessary; if not, it gave the information to the workers themselves so they could decide what to do and solve the problem.

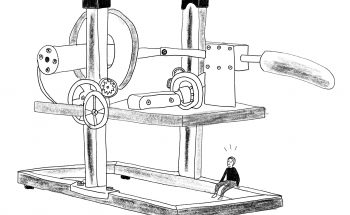

If you google “Cybersyn” or “Synco,” which was the project’s Spanish name, one of the first things that’ll come up is a picture a ‘70s-style but futuristic room. It looks like something straight out of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick.

It’s a hexagon, with a dark grey carpet. On the walls, which look like they’re made of wood, there are several screens. In the middle of the room, there are seven swivel chairs in a circle. They’re made of white fiberglass, with orange felt. On one arm of each chair there are a few large buttons and on the other, there’s an ashtray and a cup holder. That room was the prototype for the operations room. Cybersyn’s brain.

The lead designer of this room was in charge of a team of young designers and a key figure in the development of the project. This man…

[Gui Bonsiepe]: My name is Gui Bonsiepe. Despite having a kind of weird name, which sounds French, I’m actually German.

[Natalia]: Gui studied information design at the Ulm School, a German college that became famous globally for its innovation in design. Gui liked Latin America. He had already been to Buenos Aires at a meeting for his design school and later he taught a course there in the mid-’60s.

So when he got an offer in 1968 to go to Chile, he didn’t think twice. He worked as a professor and then at CORFO as an industrial designer. And there, his boss picked him to design the Cybersyn operations room.

[Gui]: Sometimes it’s been described as a… a futuristic room, we would say, like a spaceship. Well, that seems like a bit of a stretch to me. That wasn’t our intention (Laughs). We just wanted to make a comfortable operations room, one that was suited to the functions it had to perform.

[Natalia]: And those functions —which Beer himself had given them— were very specific. Among them was that there would be nothing having to do with paper, not even tables.

[Gui]: We were surprised, you know? I mean, a meeting, a meeting room without a table. What is this? “No,” he says. He had put a sign on the entrance: “Carrying written reports, right?, under your arm was prohibited.” That was a room for thinking and making decisions.

[Natalia]: So, everything you see in the picture of that room, had a reason for being. For example, there were seven chairs because —according to Beers ideas— seven was the maximum number of people that can be in a group to be creative.

The chairs were connected to the screens on the walls with tables under the floor and the buttons on the armrests changed the images on the screen. For Beer, it was very important that information —and the operations rooms itself— could be understood and controlled by anyone, not just specialists.

[Gui]: Through that operations room, the whole complex system could be used.

[Natalia]: For that reason, the buttons on the chairs were large and had simple shapes, which even someone who wasn’t familiar with typing could use, like the workers at the factories. And the information that appeared on the screens, couldn’t just be a bunch of numbers either.

[Pepa Foncea]: It was our job to graph the information so it could be presented on the screens in the operations room.

[Natalia]: This is Pepa Foncea, a pioneer in graphic design in Chile. The design team he worked on had to make graphs that could replace…

[Pepa]: The reports, a number of pages visually, at just a glance.

[Natalia]: To do that, it wouldn’t work to just have charts and graphs, so they produced flowcharts to visualize different stages in a process. And that, in terms of design was…

[Pepa]: Very revolutionary because getting people to understand several industrial processes through a graph when they don’t come from the visual world is really a tremendous challenge.

[Natalia]: At that time, Cybersyn —and Chile— were at the forefront of design.

So, let’s review: all the information was collected —in real-time— with the Cybernet network, the telex machines. Then, the software that they had designed —Cyberstride— filtered all that information and brought the relevant data to the Operations Room, where it was converted into graphs so the people sitting in those seven chairs could understand then and that way decide what to do. This is, in short, what Cybersyn was.

It was a very ambitious process, but they were working in a very precarious position.

[Gui]: It was an operations room that started working almost as an artisanal product.

[Natalia]: For one, there were problems that had to do with the time, for example, all the sheets and drawings that Pepa spoke about were made by hand because there were no design programs like the ones we have today. But also, its precariousness had to do with the blockade that the US had put in place against the Allende government.

Still, Beer and everyone at CORFO was thinking big. Cybersyn was completed with CHECO —which by its English initials means Chilean Economy— a program that was supposed to make the short term projections that Cyberstride was making for factories and companies, but in this case, they would be medium and long term and they would apply to all aspects of the country’s economy.

[Daniel]: The idea was that eventually the entire Chilean economy would work with Cybersyn. And perhaps that best way to see if it worked or not was to put the project to the test in a real crisis.

We’ll be right back.

[Up First]: While you were sleeping a whole bunch of news was happening around the world. And Up First is the NPR news podcast that gets you caught up on the big news in a small amount of time. Spend about 10 minutes with Up First from NPR, every weekday.

[Pop Culture Happy Hour]: There’s more to watch and read these days than any one person can get to. That’s why we make Pop Culture Happy Hour from NPR. Twice a week we sort through the nonsense, share reactions and give you the lowdown on what’s worth your precious time. Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour Wednesdays and Thursdays.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, we heard about the meeting of Englishman Stafford Beer’s cybernetics and President Salvador Allende’s socialist project in Chile, and how from that meeting Cybersyn emerged, a project which apparently would change the Chilean economy.

In 1972, Beer had already been traveling between London and Santiago for a year to develop different areas of the project and everything appeared to be going rather well. But, beyond the project, the situation in Chile was getting more and more turbulent, complicated. Not just because of the economic blockade, but also because of the opposition. And in October of that year…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Voice]: Enough ruses! Enough zigzagging! Let’s take this problem head-on! For tariffs, for replacements…

[Journalist]: Separate industries came to a standstill successively, demanding a corrective response.

[Daniel]: Truck drivers went on strike all over the country. They wanted to destabilize the Allende government.

Natalia continues the story.

[Natalia]: The strike that started in Chile toward the end of 1972 was known as “the trucker’s strike” or “the boss’ strike.” It was being promoted by groups that opposed the Allende government and its socialist ideas.

Two days after announcing the strike, more than 40.000 trucks had stopped running all over the country. All products —food, fuel, raw materials— stopped being transported throughout Chile. Things were looking rather bleak. This is Raúl Espejo, again, the director of Cybersyn.

[Raúl]: The critical point for the project was in October of ‘72.

[Natalia]: When the strike started. And Raúl says that it was critical because it was then that Cybersyn was put to the test. We’ll explain: the truck drivers who were on strike worked for private companies, but the government had its own trucks, which…

[Raúl]: Most of the time, especially if there was no commercial or industrial activity, they were parked there.

[Natalia]: There weren’t many —about 200 trucks compared to the more than 40.000 that were on strike —but with the help of Cybersyn— the telex network they had already set up— they were able to put them to work.

[Raúl]: So by… by… by managing information on the communication networks, we were able to communicate with people who needed food, who needed water and anything you can imagine.

[Natalia]: The government was able to make decisions quickly, leaving bureaucratic paperwork to the side. The system responded to the needs it faced and Cybersyn showed its potential. More than technological advancement, Beer’s ideas showed a new way to organize, to cooperate. With those 200 trucks, there were able to meet the countries basic needs.

[Raúl]: And that was an ecstatic moment because that was really when they were working 48 hours a day.

[Natalia]: They transmitted about two thousand messages a day over telex to know where they needed materials or food, which routes where open, where they needed fuel. Everything they needed so they could do what seemed impossible: resist the strike.

After almost a month, Allende reached an agreement with the opposition so the strike would not go on indefinitely. In a conciliatory gesture, Allende named members of the armed forces as ministers in his cabinet. The strike ended on November 5th, 1972.

Raúl told us that the people who saw Cybersyn in action during the strike…

[Raúl]: Suddenly realized that these… these weren’t just telex machines anymore. They were instruments of action. They showed their effectiveness. They showed that we had a conceptualization that was powerful.

[Natalia]: And with the visibility that Cybersyn started to have, some media outlets in the UK started to attack Beer, saying that he had built Allende a machine to control Chile. They levied the criticism that Cybersyn was a centralized project, that all of the information went to a computer in Santiago. And they warned that Cybersyn could be turned into one of the most powerful weapons ever built and that Communism could use it to take over the world. These criticisms also made to the opposition’s communications media in Chile. And there was no shortage of allusions to the totalitarian world of George Orwell’s 1984.

But Beer denied all those accusations. On the one hand, he said that the issue of centralization had more to do with a lack of resources than anything else: in Chile, they only had one computer, and they couldn’t get anymore because of the blockade. And allusions to 1984 just seemed absurd to him: he saw Cybersyn as a way of achieving true freedom for workers, not a way of controlling them.

In fact, Beer imagined that Cybersyn would turn Chile into a real utopia once it was connected to another even more ambitious project: Cyberfolk. The idea was to monitor, in real-time, how the decisions they made in the operations room affected the wellbeing of the people of Chile.

The plan was for people to have a device in their homes with a dial —the little wheel that old radios have— that they could set according to their level of happiness. These devices would be connected to a network so the general level of happiness of Chileans could be displayed on screen in the operations room. In a way, it would allow Chileans to participate directly with the government’s decision-making process.

As absurd as it sounds, they managed to test out a version of this project in Chile in 1972, in two cities. Tomé, south of Santiago, and Mejillones, in the North. It was an experiment. Through the television, they connected some residents of these cities with their local government. If, for example, they were discussing a proposal, people could send signals through a number of devices, saying if they agreed or not with what was being proposed.

But while Cybersyn was concerned with trying to make science fiction a reality, the situation in Chile wasn’t improving. In March of 1973, they held parliamentary elections. The opposition hoped to reach the majority in congress —to stop the changes that Allende was making— but they weren’t able to. La Unidad Popular, the coalition of left-wing parties that supported Allende managed to win seats in parliament.

This is Carlos Senna again, who worked on Cyberstride.

[Carlos]: The situation was so difficult in Chile because when the opposition to Allende perceived that they wouldn’t be able to remove him by the parliamentary route, they wouldn’t be able to get rid of him, they started going crazy. There were nearly 20 attacks a day against Unidad Popular.

[Natalia]: They wanted to get Allende out of power however they could.

Raúl, the Cybersyn director, remembers that in early September of ‘73…

[Raúl]: Orders came in to transfer the operations room to La Moneda.

[Natalia]: To La Moneda, the government palace. They wanted to move it out of CORFO to officially establish it in the palace. They asked the Cybersyn team to organize the transfer. Gui Bonsiepe, the lead designer, remembers that…

[Gui]: Allende wanted to participate in it, and he didn’t come. He was known as a very punctual and very courteous person. If he agreed to be there, he showed up. But not this time.

[Natalia]: All of Allende’s attention was tied up with something else: the situation in Chile was critical.

Just a few days later, this happened.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: Just now, four minutes before 12, before noon on September 11th, 1973 a fighter jet can be seen flying over La Moneda.

[Natalia]: Military forces had organized a coup against Allende. They sent all their troops, planes, and tanks to the La Moneda.

(SOUNDBITE FROM THE COUP)

[Natalia]: That day, Raúl was at home; he had just come home from work at CORFO when…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: This is Radio Cooperativa, September 11th, 1973, downtown Santiago is turning into a battlefield.

[Raúl]: Listening to the radio, I realized that there was already news of the coup. I decided to go to the office and from there I went to the operations room where I heard Allende’s last words, which were very emotional and very… very… very transcendent.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Salvador Allende]: This is the last chance I will have to address all of you. Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers! These are my last words, and I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain.

[Raúl]: It was clear to me that there was no going back. It was better to leave.

[Natalia]: Because the soldiers were capturing government officials, destroying offices, looking for information. Raúl was at CORFO —a few blocks from La Moneda, the epicenter of the coup— so he grabbed all the documents he could about Cybersyn and ran home.

[Raúl]: And, of course, it was dangerous going out because bullets were flying: boom, boom, boom, from all over.

[Natalia]: Carlos Senna went to Lima that same day, he had been planning it for months because of the attacks that had been going on for a while.

[Carlos]: I remember we took off standing in the aisle. The flight attendants didn’t even say: “Sit down, let’s sit down.” No. They say… when we arrived in Lima, I didn’t know anything about there being a coup underway.

[Natalia]: Carlos remembers that that flight was the last one leaving Santiago that day. Gui Bonsiepe was still in the city.

[Gui]: We knew that… that there was a climate of unrest, right? I didn’t… personally, I never thought there would be military intervention. Some of the young people in the group were taken to concentration camps. All of them were… were taken by the secret police or the public police. Some were able to leave earlier, but others were in detention for months, right?

[Natalia]: They captured Gui, interrogated him, and accused him of spreading Marxist ideas. Even though they let him go, they started following him and surveilling his home. He decided to leave with his family in October, a month later: first to Argentina and then to Brazil.

Two days after the coup, Raúl who had left his office with the Cybersyn documents…

[Raúl]: I see a pair of trucks full of… of agents from the… the army arrive.

[Natalia]: That day he was at home with his kids. The soldiers barged in and told him to go with them. They wanted him to explain something they had found: the operations room, the telex machines. According to Raúl, the person leading this group of soldiers was someone who had worked on Cybersyn. Someone on the right, in favor of the coup, who had told the new government about the project. So, the soldiers took him to his office.

[Raúl]: That office was destroyed in the process. When I got there, it was totally destroyed.

[Natalia]: While he was there, he got a call from another worker on the project.

[Raúl]: And he tells me, “Raúl, disappear. Get out of there as fast as you can.” In other words, he told me that I couldn’t stay there. So, from there, I decided to leave the country.

[Natalia]: Because they could kill him.

In November of ‘73 Raúl left Chile. Beer had gotten him a job at Manchester University. He brought with him the Cybersyn documents that he managed to take from his office the day of the coup.

[Carlos]: The loss that… that came as a result… the interruption of the project was a shame. A pain that we really can’t come back from, really. Raúl saved a few things. I got out with a few things. Stafford, of course, had things. A lot of the project was saved. A project that was almost completed, right? It was about to be born, and they stopped that… that baby from being born.

[Natalia]: They were never able to prove if their ideas were going to work, if Cybersyn was really going to bring the workers freedom and autonomy. Or if it was going to turn into the thing critics feared. Even now, it’s impossible to know.

[Carlos]: That’s unfortunate. A great sadness we all feel. Surely, Stafford died with that sadness.

[Natalia]: This is Beer again, at the conference we heard at the start…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Stafford Beer]: You know what happened on the 11th of September 1973. The whole thing came to an abrupt close. It’s sad for me, but at least I know that that happened.

[Natalia]: He says that we already know what happened in September 1973, that things ended abruptly and that for him it was very sad.

Beer wasn’t in the country when the coup took place —like we said, he never lived in Chile— but the time he spent working on Cybersyn changed him. He stopped worrying about material things: he sold his mansion and his Rolls Royce, and he went to live in a cabin in the country. He started doing yoga, writing poetry, and painting, and for a time he became almost a hermit.

It’s impossible to know Allende’s real intentions, but it’s also impossible to separate Cybersyn from the political ideology it was born in, from that idealized notion of technology with social goals. Everyone I interviewed spoke in those terms.

[Raúl]: What we did in Chile was revolutionary.

[Carlos]: The idea of real-time that Stafford was bringing —and brought— to Chile, was like talking to aliens. It was like technology to get to Saturn.

[Gui]: Of the projects we did, it was probably the most ambitious, the most utopian of all the projects.

[Carlos]: It was all very new and almost impossible to believe.

[Raúl]: Cybersyn’s great value isn’t in the development of technology. Its great value is in an organizational vision. And that is… I think that’s the legacy it leaves behind. In the end, it’s not about creating a Silicon Valley in Chile, rather, it’s about creating a more egalitarian society.

[Natalia]: More egalitarian because there was direct communication with the people and the government, and they gave them tools to be able to make improvements that would help the people of Chile.

Or at least that was the utopia.

[Daniel]: At Stafford Beer’s request, the Chilean folk singer Ángel Parra composed a song called “Litany for a computer and a baby about to be born.”

(SOUNDBITE FROM “LITANY FOR A COMPUTER AND A BABY ABOUT TO BE BORN” BY ÁNGEL PARRA)

[Daniel]: According to the singer, the “baby” in the title refers to the re-birth of the Chilean people after the socialist transformation.

(SOUNDBITE FROM “LITANY FOR A COMPUTER AND A BABY ABOUT TO BE BORN” BY ÁNGEL PARRA)

[Ángel Parra]: “Those who don’t want to people to win this fight.”

[Daniel]: Natalia Messer is a Chilean journalist. She lives in Concepción. She co-produced this story with Victoria Estrada, editorial assistant at Radio Ambulante. Victoria lives in Xalapa, Veracruz.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Silvia Viñas, and me. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with music from Jacob Rosatti. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Miranda Mazariegos, Rémy Lozano, Patrick Moseley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, Luis Trelles, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Luis Fernando Vargas, and Joseph Zárate. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Every Friday we send out an email newsletter with recommendations from our team for the weekend. Every email includes just five links for the things that inspire us: TV shows, books, other podcasts, mobile apps, online multimedia, everything. It’s a way of sharing what we like and filtering some of all the content that’s available on the internet. If you want to get it, subscribe at radioambulante.org/correo. I repeat: radioambulante.org/correo.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.

In Radio Ambulante’s next episode…

[Women]: Legal abortion in the Penal Code!

[Daniel]: The fight for legal abortion in Ecuador…

[Comadre]: Good evening, you’ve reached Las Comadres, abortion information and accompaniment network. How may I help you?

[Daniel]: From the point of view of the women who were the protagonists. Their story next week.