We decide – Translation

Share:

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

I want to start today by reading something. It’s not long. It’s the text of a section of the Ecuadorian Penal Code, a law that was drafted in 1938. In this case, it’s the law that penalizes abortion, with two exceptions: if the health of the mother is at risk or —and I quote— “if the pregnancy is the result of a rape or statutory rape perpetrated against an idiot or demented woman.”

Let’s just say I’m not that surprised that a law like this one —with such disrespectful and cruel language— was written in the ‘30s, but what is surprising to me is that up to 2008, there were no attempts to modify it.

And, well, when it the possibility of modifying that language and that law was finally discussed, it was because the entire Penal Code had to be modified to be in accordance with the new Ecuadorian constitution, which was approved that same year.

And that’s what today’s story is about. Because many activists saw the opportunity to change not just the archaic and offense language, but the entire law penalizing abortion. This is Sarahí Maldonado, one of the women who fought for this cause.

[Sarahí Maldonado]: A lot of meeting spaces were created, a lot of assemblies, training programs about safe abortions, research.

[Daniel]: To argue that safe abortion should be included in the new Penal Code, of course. This was possible because when the new bill was being discussed, it opened up a space for different feminist organizations, like the one Sarahí belonged to, to share their point of view.

But in a country as conservative as Ecuador, achieving full the decriminalization of abortion was complicated. So, the activists were at a minimum arguing for decriminalization in cases of rape.

Sarahí and her fellow feminists carried out…

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Sarahí]: Working meetings with assembly members from different political blocks, international guests coming speak at the Assembly and talking about the experience of the legalization process or decriminalization debate for abortion in their countries.

[Daniel]: It was several years of work in which they managed to get many assembly members to agree with them, and write a bill that would allow for abortion in cases of rape.

But all that effort and work was in vain because the president at the time —Rafael Correa— through the Ministry of Justice, sent his own proposal for the penal code and said that if it was modified, he would veto it.

In the code the president sent, abortion was still penalized, only now it wasn’t one to five years in prison, but six months to two years. With the same exceptions, only they replaced the terms “demented” and “idiot” with “mentally disabled.” And that was what they chose to debate in the National Assembly on October 2013.

But the feminist groups didn’t give up, and they appeared that day to protest. Standing at the podium in front of the Assembly, Sarahí spoke:

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Sarahí]: We’re here. We came as part of a movement of women and feminists in Ecuador and we want to speak on the issue of the comprehensive penal code.

[Daniel]: And well, as you’re about to hear, there are people speaking behind her.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Sarahí]: This new proposed penal code deepens methods of control over our decisions and over our bodies and over our lives.

[Daniel]: She presented data to support her position.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Sarahí]: Abortion is the second leading cause of maternal mortality in our country. One in four women suffers sexual violence in our country.

[Daniel]: Because that year, 30 percent of these rapes resulted in unwanted pregnancies. That’s why, that decriminalization was an urgent need for Sarahí and the other feminists that accompanied her.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Sarahí]: And what does the State do? Every death, every teen suicide due to unwanted pregnancy in this country after the penal code passes will be your responsibility.

[Daniel]: When Sarahí was done saying this, another activist went up to the podium. She talked about the need for sex ed, the importance of having access to contraception, and how urgent it was to access to safe abortions to keep so many women from dying. And we she said…

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Woman]: We represent vulnerable bodies, raped bodies, murdered bodies, and for that reason, the bodies that fight.

[Daniel]: She and Sarahí took off their jackets and revealed their naked torsos, on which they had painted slogans in favor of decriminalizing abortion. At the same time, the women who supported them and who were inside the Assembly also took off their clothes. Others applauded and chanted.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Women]: Legal abortion in the Penal Code! Legal abortion in the Penal Code! Legal abortion in the Penal Code!

[Daniel]: The Assembly guards went up to them and removed them. There’s a video of that moment and it’s something you have to see: they look strong, committed.

[Sarahí]: A bunch of assembly members said they were in favor. Some masterful speeches, like super inspiring, super hopefull with a focus on rights, alluding to social justice.

[Daniel]: And one of the assembly members Sarahí is talking about was Paula Pabón, from Alianza País, Rafael Correa’s political movement.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Paola Pabón]: We would like to think that the State doesn’t want to lay its hands on women’s bodies. We would like to think of a society that doesn’t politicize embryos or politicize fetuses, but protects the lives of women.

[Daniel]: When she finished speaking, Pabón moved to discuss the article that criminalized abortions and, as such, raise the possibility that abortion in cases of rape be legal.

From Quito, our producer Lisette Arévalo continues the story.

[Lisette Arévalo]: When Paola Pabón presented this motion, she says that she felt…

[Paola]: A lot of anguish, a lot of emotions. In addition to feeling a lot of responsibility, you know? Knowing that there was the possibility to, uh, know that I was going to speak on behalf of many women, right?

[Lisette]: Pabón had participated in meetings with feminists like Sarahí, so she was already aware of the deed to decriminalize abortion in cases of rape. That’s why when she presented the motion, a lot of assembly members supported her and the president of the Assembly accepted the motion. But when they were about to open the floor for a vote, the assembly members from Alianza País requested a recess and called their block to a meeting. After 40 minutes, they came back and…

[Paola]: It was chaos. The session was suspended. And, after the motion was raised, I got in my car. I left the driveway like this. I went come. I didn’t pick up anyone’s calls.

[Lisette]: All this commotion —suspending the session of the Assembly until the following day and Pabón’s leaving so abruptly— took place because a few months earlier, some assembly members from Alianza País had met with Correa to discuss his bill. That day they decided that what they agreed on in that meeting would not change in the assembly debate. That’s why Pabón’s motion was so problematic: it was going against what had been agreed upon with the president.

So, after the session was suspended, many assembly members from Alianza País stayed at the Assembly that night to discuss what they could do.

Pabón didn’t participate in those discussions. She was at a meeting in her living room with her staff. And after a few hours, they heard President Rafael Correa on TV talking about what had happened at the Assembly.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Rafael Correa]: Look, they can do what they want. I will never approve the decriminalization of abortion beyond what exists in current law.

[Lisette]: He accused the assembly members of betraying the Alianza País movement by presenting positions that were different from what they had decided earlier. And he went on, saying…

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Rafael Correa]: If a group of very disloyal people achieve a majority in the Alianza País block, do what you will, I will immediately resign from my post because when it comes to abortion I am ready, and my principles are as well, to defend life. I’m prepared to resign, and history will be the judge.

[Lisette]: Yes, Correa went on national television to say that if they passed abortion in cases of rape, he would resign as president. When Pabón and her team heard him…

[Paola]: Everyone started crying because in the end… I mean, we knew that it was a David and Goliath situation. And of course, that was painful for us. It was very painful for us because we would have liked for the political project as such to support the position as well, you know?

[Lisette]: Her president’s potential resignation had a particular impact on Pabón, especially since she was the one who passed the motion.

[Paola]: Yes, so it was a painful hit, you know? No, I wouldn’t have imagined that kind of reaction. I felt… it’s like your walking down the sidewalk and all of a sudden a 60-story building comes crashing down on you and you don’t know how you’re going to be able to get out of this craziness and how you’re going to be able to get air and breathe and say: “No, I’m alive. I’m going to survive.”

[Lisette]: After that, she didn’t meet with anyone else. She didn’t leave her house. She didn’t turn on her cell phone. She decided to wait and see what would happen the next day.

Meanwhile, the feminists who went to the Assembly were also waiting to see what would happen. Here’s Sarahí.

[Sarahí]: I remember there was an anxiousness we all had… it was a big feeling of anticipation.

[Lisette]: Even though she was bothered by Correa’s statements, she went to bed with a lot of hope.

The next morning, Sarahí got in the car with her family and while she was driving to meet with her fellow activists outside of the Assembly.

[Sarahí]: And all of a sudden, at 9:12 a.m. I was listening to the radio while I was rushing to the Assembly, because it was like a party.

[Lisette]: On the radio they were airing the debate and Pabón, the assembly member, started responding to what Correa had said the night before.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Paola]: I never thought that defending the lives of women, that condemning rape, that making Ecuadorian society face the fact that in this country women are raped and may have abortions would generate a reaction like this.

[Lisette]: She added that…

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Paola]: With the same courage with which yesterday more than 20 members of this Assembly defended women, I am telling you Rafael Correa that there are no traitors here. This is a decision for the 5 million Ecuadorians who believe in the Citizen’s Revolution. We will not break apart. We are not going to allow this to debilitate the process that has given hope back to the men and women of Ecuador.

[Lisette]: And there she announced that for the sake of the unity of her block of assembly members, Alianza País, she had made a decision.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Paola]: My fellows, I withdraw the motion so that this block may not run the risk of rupturing.

[Lisette]: In other words, Correa won. They weren’t even going to discuss the proposal to decriminalize abortion in cases of rape anymore.

[Sarahí]: I was driving and I said: “I can’t believe it. I can’t believe it.” And my family was saying: “No, calm down. I don’t think that’s what it means. Someone else has to oppose it and they have to…” And I was just… by then I was crying while I drove and of course when we got there it was a… a frustration. It was like one of the clearest displays of political violence we’ve experienced.

[Lisette]: When I asked Paola Pabón how she made that decision, she told me that that day she met with some other assembly members in Alianza País at the Assembly and she saw them…

[Paola]: I mean, everyone was already in tears, everyone was in tears and in despair. Besides, that was one of the things that really upset me: seeing my fellow assembly members crying, very upset, very overwhelmed, very unsettled. It was a very difficult process for everyone in the block.

[Lisette]: Because, Pabón says, with Correa’s threat, their movement and their plan for the country was at risk. And that’s why the other legislators in her block asked her to withdraw the motion. She accepted because she wasn’t going to let her president resign and because she didn’t want to put her fellow legislators in a difficult position. She says she doesn’t regret the decision but…

[Paola]: If I were sure that I was going to have the votes, I wouldn’t have withdrawn the motion.

[Lisette]: She says that because before the president’s statement, she was counting on votes from other members of Alianza País to decriminalize abortion in cases of rape. But with Correa’s potential resignation, they withdrew that support. For Pabón…

[Paola]: After withdrawing the motion, for me it was a… I cried a lot. A lot. A lot. I didn’t want to know what was going on in the world. Withdrawing the motion had a very, very high personal cost for me.

[Lisette]: Because for Pabón and two other assembly members, it didn’t end there. After a few weeks, Alianza País’ ethics committee sanctioned her for “not respecting agreements.” Or, in other words, for promoting the decriminalization of abortion in cases of rape. They went a month without working at the National Assembly and they stopped making statements to the media.

The new penal code was passed into law on February 2014, and the right to abortion in Ecuador remained very similar to how it had been since 1938, which Daniel mentioned at the start of this story. With only one significant change: the penalty was reduced from between one to five years to between six months and two years in prison. And well, they also replaced the word “demented” and “idiot” with “mentally disabled.”

Let’s get back to the scene at the Assembly, when the two activists took off their jackets in the middle of the debate over legal abortion. This act of protest was no improvisation. On the contrary. It was part of a struggle that had been going on for years. Context is key: 16 percent of maternal deaths in Ecuador are a result of abortions in unsafe conditions.

And “unsafe” can take many forms. There are women who drink detergent, bleach, acid, poisonous infusions, excessive doses of medication. Others insert clothes hangers, knitting needles, tree branches or wires into their vaginas. Others leap from tall heights hoping the fall will cause an abortion. Others go to so-called clinics which are unsanitary, that don’t have the necessary instruments nor qualified doctors to do the procedure.

And this lack of options doesn’t just affect women, but also teenagers and young girls. Ecuador is ranked third in the region in rates of teen pregnancy. And every day at least seven girls under the age of 14 become pregnant, most of them victims of rape.

Knowing that this occurs is what caused many women to fight for safe abortion in the country. In 2008, for example, they created the first hotline in Ecuador—and in the entire region— that gives information about safe abortion using medication. This hotline is called Salud Mujeres and when it had just started, it got more than 100 calls a day from women all over the country who wanted to have an abortion.

But when the penal code passed into law, upon seeing that the State wasn’t going to address this need, Sarahí and her fellow activists decided to create a solution out of that disappointment and defeat. A possibility for all women who wanted to have a safe abortion with medication in the country. Here’s Sarahí.

[Sarahí]: We needed to think of a solution that close the cycle. Not just give information.

[Lisette]: Now, they also wanted to accompany women while they underwent the procedure and have a physical space where women could share their experiences.

[Sarahí]: After we lost we said: ”Now, let’s create another space. One that can provide information. That give support, help women get the medication and from there we can develop a friendly network of other services like doctors, psychologists, and lawyers.”

[Lisette]: They started to look for a name.

[Sarahí]: Few of us from that first group were very creative. So…. (laughs) it was very hard. And we threw out names. Some of them were super… out there. But all of sudden someone said “comadres.” And we all realized. We said: “No, no, wait that’s it. It can represent a the role of a friend, a confidante, a… yes, an accomplice.”

[Lisette]: A comadre in Ecuador —like in many other Latin American countries— is a friend, a “partner-in-crime” who goes with your everywhere, who you can tell your secrets, who gives you advice. And in a country like Ecuador, where abortion is unsafe and illegal, that’s exactly what a women who wants an abortion needed.

So, in 2015, the network was officially established. Las Comadres

[Sarahí]: We have a hotline which is 0998883339. Someone is normally answering that phone between five and ten p.m.

[Lisette]: They advertised their number on social media and people started calling them right away. At first they got 10 calls a day, then 20, 30, 40. And the more they advertised on social media, the more people contacted them. The demand for this information was evident from every one of those calls.

And the network ended up being very relevant because after that failure to decriminalize abortion, there was a change of attitude toward abortion in Ecuador. This is Ana Cristina Vera. She’s a lawyer and also a member of Las Comadres.

[Ana Cristina Vera]: What Correa accomplished was positioning abortion as a negative topic, like no one had managed before. Previously, abortion was an obstetric emergency and it was treated that way even though socially people might tell you they didn’t agree, like ‘how could you have an abortion,’ you understand? People didn’t file reports on women for having an abortion.

[Lisette]: And yes, it may sound simple and easy to put all of the responsibility on the president at the time, but he was a man with a lot of influence and every more so in 2013 when his party was in the majority in the National Assembly.

[Ana]: So, what happens with Correa is that the practice of abortion begins to be experienced in a different way, and it begins to be treated differently in health center hospitals, and people begin reporting women, and you start being able to really feel the penalization, if you will, from exactly that point on, the criminalization of women.

[Lisette]: Ana Cristina is talking about reports from the hospitals because in the same penal code reform, something else was approved: death due to professional malpractice was penalized.

That basically meant that if someone died at the hands of a doctor as a result of malpractice, the doctor could go to prison.

The law is very complex and it was a very controversial subject because of uncertainty over how it would be applied. Especially because doctors believed that if a patient died, any relative could report them and send them to prison, regardless of what their health condition was. This created an environment of extreme panic and they were afraid of being reported.

But, besides that, this had a direct impact on women who had abortions because a lot of times —motivated by fear of penal consequences— doctors and nurses ended up reporting them for the slightest suspicion. They would rather put the responsibility for a potential crime on the women and not themselves.

[Ana]: Most women who are penalized for abortion are reported by health services when they come to get medical attention for the obstetric emergency. Of the information we have, 70 percent of these women never said that they attempted to have an abortion, they just came in with bleeding.

[Lisette]: Ana Cristina knows this because she defends these women in court. She says that, in addition to that, there have been cases of women with miscarriages —in other words, involuntary abortions— who have also been penalized because health professionals report them thinking that they are induced abortions. In 2013 —the same year that the whole political discussion about decriminalizing abortion in the Assembly took place— 45 percent of cases of women penalized had had miscarriages.

Ana Cristina says that when women show up at hospital bleeding…

[Ana]: If the health professionals think that there may be a crime, what they do is keep them there for hours and hours without waiting on them. We have cases of women who’ve spent seven, ten, twelve hours without being seen.

[Lisette]: And when the police arrive…

[Ana]: The women don’t know. They say: “Tell me what happened. Tell me everything. Nothing’s going to happen. It’s better if you tell me… if you tell me, if you don’t tell me you’ll get in trouble.” They trick them and the women end up saying things that didn’t even happen because they make getting medical attention a condition of their talking.

[Lisette]: They take blood samples. They interrogate them insistently. And, after all that, the prosecutor processes the women right there in the hospital. Most of the women who go through this and are outside of the capital get preventive detention —which can last up to six months.

However, if the woman is processed in Quito she can receive alternative measures, like appearing before the prosecutor every so often leading up to the day of her trial.

According to Surkuna —the feminist organization that Ana Cristina directs— since 2013, almost 400 women have been reported and processed for abortion in the country. These reports increased substantially after the penal code was passed into law.

But not all of these women have gone to prison because they can request alternative measures—like doing community service— because the sentence for abortion isn’t high —two years at most.

However, Ana Cristina says that the abuses don’t end at the trials. Sentences are given to punish the woman for having an abortion, for renouncing her motherhood. Like one case that Ana Cristina took on where the judge sent the woman to…

[Ana]: Volunteer at an orphanage to learn how to be a mother and develop a maternal instinct. And that’s how it’s written in the sentencing document. So, you see that sort of thing as well. In other words, absolutely sexist alternative penalties. Do they send men to take care of children at daycares, right? But it has to do precisely with pushing you toward that role. That’s what you have to be in life: you have to be a mother.

[Lisette]: According to Ana Cristina…

[Ana]: That was one of the biggest impacts: criminalization, reporting from public hospitals. Especially because all of a sudden it was as if the health professionals had learned that miscarriages were illegal.

[Lisette]: But this prosecution, mistreatment, and penalization are not factors that stop women from seeking abortions. All it accomplishes is having them do it unsafely, and —for fear of being treated like criminals— they end up not going to the hospital when there are complications and many of them die. These terrible figures and stories that have made the battle to decriminalize abortion greater and greater in Ecuador. There have been marches under different slogans.

(SOUNDBITE FROM MARCH)

[Women]: Legal abortion in the hospital!

[Lisette]: They’ve marched in Quito, Guayaquil, Cuenca.

(SOUNDBITE FROM MARCH)

[Woman 1]: We’re here today to defend the rights of women, over our bodies, to be able to make choices about our bodies.

[Woman 2]: For the legalization of abortion, which will be free and accessible to everyone.

[Woman 3]: We support the international struggle for unrestricted, safe, and free abortions because we know that clandestine abortions that result in death are killings by the State.

[Lisette]: But these movements also have their counterpart at the national level. From people like these:

( SOUNDBITE FROM MARCH)

[Man 1]: Legal or illegal, abortion kills all the same! Legal or illegal, abortion kills all the same!

[Man 2]: Today we’re marching as a church to defend life.

[Woman 1]: I am marching for life because life is a gift from God and only he can take it away.

[Woman 2]: To reject abortion.

[Man 3]: For life. No to abortion. No to death.

[Lisette]: These marches take to the streets under the slogan “We’re saving two lives.” And are organized by different groups, mostly Catholics and Evangelicals and, especially, people who call themselves “pro-life.” One of these groups is the Life and Family Network Ecuador. And since 2010 their president, Amparo Medina has led marches like the ones we heard. She explained that her goal is…

[Amparo Medina]: To awaken the feeling within people that inside a mother, there’s a life and that life has to be cared for and protected by every single Ecuadorian.

[Lisette]: And she maintains that position for all cases. Even if the woman is raped and becomes pregnant.

[Amparo]: We believe that no Ecuadorian should be discriminated against because of who their father is. Besides, no one chooses how they’re conceived. Neither you nor I chose the circumstances under which we were brought to term.

[Lisette]: And she told me the woman should be punished for having an abortion because it’s a crime. The ones who should go to jail are the doctors who perform abortions and also…

[Amparo]: Everyone who promotes, advertises, and performs abortions. Salud Mujeres, Las Comadres are the ones who are selling chemical abortions, and they should go to prison.

[Lisette]: What Amparo said about Salud Mujeres and Las Comadres selling medicine isn’t true. When I told her that these groups only provide information, and that it isn’t illegal in Ecuador, she responded…

[Amparo]: It’s like contract killing, isn’t it? If you give someone information about how to kill another person, obviously I’m promoting the murder and promoting the murder of any human being should be punished.

[Lisette]: Amparo Medina says “human being” because for her and the groups she represents, life begins at conception. And even though this is the topic of a lot of discussion and controversy, the position depends on a person’s religion or philosophy.

But the discussion goes beyond when life begins. It’s also a public health problem. Not just in Ecuador, but in many parts of the world because, like we already said, there are many women who are dying from unsafe abortions, and who are denied medical attention in suitable conditions. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 30,000 women in the world die every year in dangerous abortions.

But, going back to Ecuador, it’s in this social and political environment of constant disagreement about abortion that Las Comadres exists. That’s why they believe their work is the perfect response to what is happening with the legal and social criminalization of women having abortions. To Ana Cristian Vera, what’s central here is that…

[Ana]: It’s women who stand with women. To me, like I told you, that is symbolically very important.

[Lisette]: Because that builds trust and allows to live the experience of abortion in a different place, far from unsafe clinics and stigma. A safe abortion, at home and with friends, with your comadres. And the most important thing for Las Comadres to achieve this is…

[Ana]: We consider an accompaniment from a position of not judging, you understand? The woman’s reasons, or why she’s doing it, instead we’re just trying to make this information available to women who need it. And also if they need to have a conversation, talk about something, they can do that.

[Daniel]: After the break, we’ll see how Las Comadres works, what that process of accompanying women is really like.

We’ll be right back.

Ambulantes, we need your support to keep telling the audio stories that bring you closer to Latin America. That’s why we’ve just started a membership program. When you become a Radio Ambulante member, you will receive several benefits and, most importantly, you will help us keep growing and producing new episodes and new Spanish language podcasts. For more information visit our website, radioambulante.org. Thank you!

[Alt. Latino]: Hi, I’m Félix Contreras, from the Alt. Latino podcast. This month, when we celebrate our history and heritage, I would like to remind you to check out Alt. Latino. I’ll be having shows about Mexican music, the influence of Latin music on rock and roll, and much more. Subscribe to Alt. Latino and join the fun.

[Pop Culture Happy Hour]: There’s more to watch and read these days than any one person can get to. That’s why we make Pop Culture Happy Hour from NPR. Twice a week we sort through the nonsense, share reactions and give you the lowdown on what’s worth your precious time. Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour every Wednesday and Thursday.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, activist Ana Cristina had created a support group of women for women called Las Comadres. And, well, we wanted to see how it worked. So Lissette, our producer met…

[Michelle Játiva]: My name is Michelle, Michelle Jávita. I’m 25 years old.

[Lisette]: Michelle is a psychologist, and she lives in Quito.

[Michelle]: I really followed Las Comadres for a few weeks before needing them.

[Daniel]: Lissette continues the story.

[Lisette]: Two years ago, when Michelle was about to graduate from college, she heard that Las Comadres were going to give a talk about safe abortion in Ecuador. And she wanted…

[Michelle]: To go see this space, what these girls were saying, what’s their plan, what is the topic like in terms of mental health. I wanted to immerse myself in the topic.

[Lisette]: But the day before the discussion.

[Michelle]: I found out that I was pregnant. That hit my very hard because I found out I was pregnant and it was like: “That can’t be.” I don’t want to be. Being a mother wasn’t part of my plan for my life at that time. I’d be lying if I said that at any point I said: “No, I’m going to think about it.” The first thought that came to my mind was: “No, this can’t be.”

[Lisette]: Michelle talked to her partner about it and between the two of them, they looked for options. A friend told her that she knew about a secret clinic that was supposed to be safe.

[Michelle]: We checked and the abortion would cost me 500 dollars. Five hundred dollars which was a lot.

[Lisette]: Of course. That was a lot of money, especially since she still hadn’t graduated college. But her boyfriend told her that between the two of them they could find a way to pay for it. With a lot of effort, of course. Getting $500 overnight isn’t easy. And, even then, Michelle wasn’t sure because after all it was a secret clinic and she was afraid that something might happen.

[Michelle]: I didn’t know what to do. I said: the option is to have an abortion. But I had all those things in my head: it’s very unsafe, they scrape out your uterus, it’s horrible.

[Lisette]: So, before deciding to go to the place she had been recommended, she wanted to wait for a day, go to the talk, and see what happened.

[Michelle]: When I went to where the Comadres were, I was extremely nervous because I was saying: I hope they can help me.

[SOUNDBITE FROM ARCHIVE]

[Woman]: Sharing with you what our political objectives are as a network. Among them is, well, taking abortion out of the shadows.

[Michelle]: When I arrived, I heard the… the talk, and I was so nervous that I couldn’t go up to say anything to them. I just listened to the talk, and what I did do was pick up the… the fliers. I got every… everything they were giving out.

[Lisette]: And she went home. Michelle sat down to read all the information and process what she had heard at the talk. Then she saw that Las Comadres had a phone number for safe abortion accompaniment. She went to sleep thinking about her options, about what she should do. And the next day, at night, she decided to pick up the phone and call the number on the fliers.

[Sarahí]: Good evening, you’ve reached Las Comadres, abortion information and accompaniment network. How may I help you?

[Lisette]: Las Comadres explained what they do.

[Sarahí]: What we do is give information about safe medical abortions, we accompany women who needs information before, during, and after the process to have a safe abortion.

[Lisette]: So, let’s go through it one by one. Before.

[Sarahí]: That’s when we provide information at these in-person group meetings.

[Lisette]: These meetings are only available for women who are in cities where the network operates, cities like Quito, Cuenca, and Esmeraldas for now. Right now, for the women who are in other cities or in rural areas, they only accompany them over the phone.

But when they’re able to, they meet in a public place. And that’s important because for them…

[Sarahí]: We believe that talking about abortion in common, everyday spaces helps to remove this stigma about abortion as something that’s risky or bad, that’s something secret.

[Lisette]: In Michelle’s case, once they gave her all this information, they asked her for some general information. They asked her if she took a pregnancy test and if she was sure she’s it wasn’t an ectopic pregnancy —that is, a pregnancy outside of the uterus— because in those cases it’s safer to have a surgical abortion in a hospital. And you have to keep in mind that in those cases it’s legal because the life of the woman is at risk.

After clearing up those questions…

[Michelle]: They told me to meet them at the place they gathered at the time. I remember I was… I was so nervous.

[Lisette]: They asked her to wear something distinctive —like a hat or a scarf that she would wear that day— so they could identify her.

Michelle said she was going to wear a black blouse and went to the place where they said they would meet: it was a cafeteria at the university in Quito. She got there and sat to wait. A few minutes later, the two comadres who had set up the meeting came up to her and took her somewhere where there were more women who were there for the same reason.

[Michelle]: So, I was really nervous. There was another girl who was more nervous, and there was… there was a girl that had already done it. And it was… for me it was a huge relief, to see myself in another person who went through the same thing as me, who was explaining this to me. For me it was… that was what put me at ease.

[Lisette]: And once they’re all together, Las Comadres tell them how they can have a safe abortion using medications that are recommended by the World Health Organization: misoprostol and mifepristone.

Misoprostol usually requires a prescription from a doctor. But there are also pharmacies that sell it at very high prices or on the black market. Like 200 dollars for four pills. You have to keep in mind…

[Sarahí]: In Ecuador you can’t get mifepristone. It’s a medication that isn’t included in… in the set of basic medications. But because of a partnership we have with Women on Waves, they can —the women we accompany— have access to that medication.

[Lisette]: Women on Waves is a Dutch non-profit organization that was created in 1999 by doctor and activist Rebecca Gomperts. And what this organization does is travel by boat to countries where abortion is illegal and provide contraceptives, information, workshops, and safe legal medical abortions.

Woman on waves has an operating license from the Dutch ministry of health that allows them to perform abortions on their boats up to the third trimester.

And bringing this service to other countries is possible because it’s based in maritime law: when a boat is in international waters, the boat is subject to the legal system of the country it belongs to. So, since the boat is from the Netherlands —and is governed by its laws and the authorization that that county gave them— it’s legal to have an abortion on the boat when it’s anchored in international waters.

For example, they go to countries like Mexico —where it’s only legal to have an abortion under any circumstance in Mexico City— and they pick up women in a port there, take them to international waters, and help with safe abortions. When the process is over, they take the women back to the Mexican port.

But, since this reaches few women, they have another initiative called Women on Web, and this works because…

[Sarahí]: They send the medications to a bunch of countries where abortion is penalized.

[Lisette]: This organization asks the woman that wants to have an abortion for a donation to ship the pills, and the amount is between 80 and 100 dollars more or less depending on the economic circumstances of the person making the request. If a woman can’t pay, they give out scholarships or donations so they can access the medications without any costs.

[Sarahí]: The partnership with Las Comadres makes it so that women don’t have to pay; instead they can make a contribution to Las Comadres and then we take care of returning the favor.

[Lisette]: With the contributions they receive, Las Comadres also help women with limited resources buy sanitary napkins or sometimes rent a room in a hotel because they may not be able to have the abortion at home.

But if the women don’t have the money to make a contribution, it’s no problem, they’re accompanied in the process all the same.

Of course, every accompaniment is different because every woman has a different context or sometimes they have medical histories that need to be taken into account. Like Michelle, for example.

[Michelle]: There’s a form where you say if you have any illness. So, I said I had a heart problem. So, she said to me: “Gosh, you know what? We’re going to have to talk to… to the other volunteers. I’m not going to fill out the form yet. I’ll schedule you later.” And, that was it.

[Lisette]: Michelle thanked them and went home. She wasn’t sure if they could help her because of her heart condition. But she took comfort in the fact that they didn’t say “no” right away. Beside that, she left feeling confident, calm, and safe. After a few days they called her and asked her to meet with them again to talk.

[Michelle]: I remember everything. I remember the place, the time. I went with my partner. We went together and he told me: “No, but who are these people?” And I was very confident in them.

[Lisette]: Michelle and her partner met with two comadres.

[Michelle]: And, well, they said: “Ah, hello, how are you? Come in. Look, we’re going to explain everything.” And… oh, they explained everything. Everything, everything, everything.

[Lisette]: They told her that they had spoken with a doctor, with a gynecologist, with all of the doctors in their network to see what options she had.

[Michelle]: And for me it was, like, my God, these two women who I’ve never seen in my life, and they haven’t seen me either, are helping me in a way that… I mean, they didn’t ask me for money or anything, you know? Nothing. It was just… it was: “Oh, I mean, you’re in this. You’re not alone. We’re with you.” And I got emotional right now. Because I remember that and for me that was very meaningful, really. Because I said: “Wow, I’m not alone.” They never told me: “You have to do this.” They told me: “Look, here are all the options. Think about what you want to do.”

[Lisette]: Michelle left that second meeting with her mind made up. She was going to have an abortion with Las Comadres. And that takes us to the second stage of Las Comadres’ accompaniment: what they provide during abortion process itself.

[Sarahí]: We stay in contact with them over the phone or by text. Then, if any issue comes up, any question, if they want to share something, they have their comadre to talk to, to write to.

[Lisette]: On top of that, it’s important to them to be available during the process in case they have a complication and need to go to the hospital. Especially because the risk that they won’t get the necessary medical attention or be criminalized —even though it’s impossible for a doctor to identify a medically induced abortion, because the symptoms are the same as a miscarriage.

A week after that second meeting with Las Comadres, Michelle got the pills in the mail. It was March 8th, to be exact, International Women’s Day.

[Michelle]: I called my comadre. She explained it to me again because I had forgotten a few things.

[Lisette]: Then she took the pills as instructed and…

[Michelle]: I started the process and, I started having symptoms right away.

[Lisette]: Some of the normal secondary symptoms that can occur: fever, chills, nausea, abdominal pain like cramps, or vomiting. She called her comadre again, and she told her to take an analgesic for the pain and to put a heating pad on her stomach.

[Michelle]: From there, well, I applied a heating pad. My temperature went down, but the chills didn’t stop.

[Lisette]: Meanwhile, she had the bleeding, that is, the indication that the abortion was underway, and she got in the shower. Then she went to bed and fell asleep. After a few hours.

[Michelle]: I felt fine. I just felt a little pain in my hips, on my waist, sorry, and that was it.

[Lisette]: Not long after, her boyfriend arrived, she ate and laid down for bed. And the next day…

[Michelle]: I felt relieved, calm. For me it was like: “Now, it’s over.” It was a weight… it was: “This is over. It’s behind me now. My God, I’m saved.” in a manner of speaking. And then I felt guilty for feeling that way.

Sometimes you don’t feel guilty because of the abortion; you feel guilty for not feeling guilty, for feeling OK, for feeling calm.

[Lisette]: Of course, not all women who have abortions feel this way. But when they do, they can process it in the post-abortion meetings, the last step in the accompaniment Las Comadres offer. Here’s Sarahí.

[Sarahí]: We don’t want to create a discourse and a practice of feminism that fails to acknowledge what women really feel. And, yes, there is guilt in abortion. But the purpose of our space is to work through that guilt together and say why we feel guilt. “I feel guilty for not feeling guilty,” a lot of women tell us that.

[Lisette]: Some time after her procedure, Las Comadres invited Michelle to one of these meetings.

[Sarahí]: They’re open spaces with women who are accompanied or not, who have had abortions and want to share what they lived through, their experience and how they understood the process of their abortion.

[Lisette]: Michelle decided to go and meet more women who felt like her. After listening to them…

[Michelle]: I felt more at peace because I said: “OK, I’m not evil , I’m not a monster, I’m a human being. I made a decision and I feel at peace. It’s my life plan. I can resume my life plan.”

[Sarahí]: A lot of times abortion is the possibility to do an x-ray of your life and be able to decide something that is transcendental. Many women, for example, have said, some of them, that it’s the first time they’ve made such an important decision about their lives themselves.

[Lisette]: And Sarahí knows because, like these, there are many more stories: women with children who don’t want to have more because they don’t have the money, women who were raped and became pregnant as a result of the rape, teenagers who didn’t have sex education on how to prevent pregnancy, women who live in rural areas of the country hours away from the nearest highway. And learning about these stories —and her experience of having an abortion with Las Comadres— awoke something else in Michelle.

[Michelle]: And from there, when I was on that post encounter, I said: “I want to do this.” I want to be that woman who other women meet and tells them: “Listen, no, it’s alright. Call me. Look, this or that.” So, I said I want to be that kind of support. I want to be that woman… who accompanies other women.

[Lisette]: And she did. After a few months Las Comadres opened a training academy for accompanying women during abortions, because the number of women calling them was already too much for them to handle. In July of 2017, they sent out the call and 200 women applied, of whom 15 where made it through all the security filters and ended up in the training process. Michelle was one of them. She became a Comadre.

[Daniel]: Now, in 2019, there are 50 comadres in total accompanying woman in safe abortions in Ecuador. According to their records, so far they’ve accompanied 2.500 women like Michelle.

But, in Ecuador in 2017, almost 10,000 women went to the hospital for complications related to “non-specified abortions” or, in other words, “clandestine abortions.”

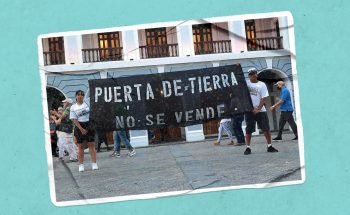

Last week, on September 17, Ecuador’s National Assembly voted on a project that would decriminalize abortion in cases of rape. It was a very emotional day with lots of protests on both sides, with hundreds of people outside the assembly in Quito.

With 65 votes in favor and 59 votes against, the bill didn’t pass. Five more votes were needed. Abortion in cases of rape is still illegal in Ecuador.

Lisette Arévalo is a producer with Radio Ambulante. She lives in Quito.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Silvia Viñas, Luis Fernando Vargas, and me. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri, with music from Giancarlo Vulcano. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Victoria Estrada, Rémy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa y Joseph Zárate. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

The Club de Podcast Radio Ambulante is a Facebook group where Radio Ambulante listeners from around the world meet to talk about the episodes and share additional information about the stories. It’s one of our favorite places online. Look for it on Facebook as the Club de Podcast Radio Ambulante to join. We’ll see you there.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.

On Radio Ambulante’s next episode, Víctor Buso, a locksmith and amateur astronomer, found a dot in the sky…

[Víctor Buso]: And I start to see a pixel… just one pixel. And I say, “What is that pixel there?” This is tremendous, I say, “If this is a discovery, I have to do it quick”.

[Daniel]: And that discovery would change his life. His story next week.