Translation – The Lives of Marilú [Part 2]

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

[Jorge Caraballo]: Hello, I’m Jorge Caraballo, Engagement Editor here at Radio Ambulante. And before we start, we have two news: one is that our season is coming to an end, and, two, that we’re going to do a special episode with you. It’s an episode where we are going to answer any questions you have about Radio Ambulante. You can ask us about whatever you want: from something that wasn’t clear in a story, to what we like to do when we’re not making podcasts.

To leave your questions go to radioambulante.org/pregunta. We will select them and make this episode with you and for you. Thank you so much: radioambulante.org/pregunta. Bye!

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

In the previous episode, we met Marilú Reyna, a woman who converted to Islam in Mexico and then moved to Spain with her husband, a Moroccan she met on the internet. If you haven’t heard that episode, please stop here and listen to it before continuing.

[Ana Marilú Reyna Castillo]: And that was it, they arrested me there. Right where that sand-colored car is. I had parked my car there.

[Daniel]: Marilú was arrested on January 23rd, 2017. She showed our editor, Silvia Viñas, the exact spot. It was outside of her older son’s school, in the morning, when all of the parents were dropping off their kids.

That day, agents from the Civil Guard loaded her in a car and took her from her son’s school to jail.

[Marilú]: And on the way, I was thinking, “Who was going to say? if I came in my car and now I’m going in another. What happened?” Everything was so… so strange, so surreal, so… like, when? I mean, when?

[Daniel]: Remember, her husband, Aziz, had been arrested almost a year before, in May of 2016. And he was still under arrest. He was being accused of leading a group that distributed propaganda over the internet, that was recruiting people and radicalizing them to join the jihadist movement. Which Marilú denies.

[Marilú]: Plus, I said: “If I had seen something strange in him, however small it may be, I would grab my kids right away and go.” I said: “But if I never saw anything strange in him, well no. I’m not going to turn my back on him.”

[Daniel]: Marilú says that the day they arrested her, now at the Civil Guard’s jail…

[Marilú]: They ask me: “Do you know why you’re here?” I say: “No.” He says: “You’re here because of terrorism.” And I said: “What do you mean because of terrorism? My husband is the one who’s under arrest.” He says to me: “Yes, yes. And you are too.” Then I said: “Let’s see, but it’s just that… but I haven’t done anything.”

[Daniel]: The day after her arrest, a judge gave her the charges: recruitment, promotion, and indoctrination.

Silvia continues the story.

[Silvia Viñas]: The detention order in which they explain why she was arrested says that they conducted a —quote— “painstaking” investigation to arrive at these charges.

It says: “In a relatively short period, she has come to display an meaningful transformation, with a rigorous esthetic…”

I read it with Marilú. In one paragraph it talks a little about her conversion to Islam, saying that in a short period of time she had changed her western appearance to a —quote— “rigorous esthetic, with the most radical precepts of Islam.” It also said that her daily activities…

[Marilú]: “Were reduced simply to childcare.” Man, with two children. And one with a… with developmental delays. And besides, me being a mother and a psychologist (laughs)… who wants her child to be well.

[Silvia]: And according to the detention order, the investigation found that Marilú didn’t have a social life.

[Marilú]: Well, I don’t know what that’s referring to. If it’s that they didn’t see me in bars or… I don’t know. Because I would go out to the park, I went with my kids to… to school, I took them to therapy. Ryane was also in karate. I would take him to karate. I was there with them. Well, I don’t know what that’s referring to. I got along with my neighbors.

[Silvia]: The document also says that she didn’t have female friends in her neighborhood, even though Marilú mentioned several female friends while we were speaking: one who took care of the kids after Aziz’ arrest; another that was a widow who Marilú welcomed into her home; another who she wanted to open a business with, selling decorative balloons for birthdays. Was she making these friends up? These plans?

I asked Marilú about something else that document says that after searching her apartment, the investigators had found —quote— “numerous multimedia materials.” Marilú believes that’s what they took when they searched that house that day when they arrested Aziz: two laptops, Aziz’ work computer and hers…

[Marilú]: Which I used. That I brought from Mexico. I had it there, well… from my job as a psychologist, when I worked at a school and all that.

[Silvia]: She also an external hard drive, a camera, an iPad, Aziz’ cellphone, and another that they had, and so on. The detention order says that among these “multimedia materials” they found photos from the Islamic State, and…

[Marilú]: “There have also appeared multiple photographs perpetrating the feminine jihad.”

[Silvia]: Later I was able to see the images this document is referring to. They’re in the case summary. There’s a propaganda poster from the military arm of Hamas, the Palestinian Islamist organization, in which several women are committing suicide attacks. In other images, there are women in veils carrying Kalashnikov rifles, and there’s also a photo of what appear to be jihadist prisoners.

[Marilú]: Well, then, show me the pictures. No, none of that is mine.

[Silvia]: The document also mentions emails, Facebook profiles. All of it, according to the investigation, showing that Marilú kept, shared, and promoted terrorist material.

And, according to the investigators, Marilú video chatted, normally on Sundays, with a group of people about Islam. The detention order says that she read pieces of writing related to the Prophet Muhammad and that she led these conversations: she advised participants on how to practice Islam and how to recruit new people.

Marilú says that when she came to Spain, she did chat with a group of friends, Muslim women who were in Mexico.

[Marilú]: How much did the conversation last? An hour at most? Between: “How are you? How’s your week going? What have you lived there?”

[Silvia]: And she says they did talk about Islam.

[Marilú]: But they weren’t deep topics or anything. Some question would come up. For example, now with Ramadan. Telling them, OK let me check. Or just the fact that I’m in a Spanish-speaking country, and there are many more Muslims, and you have more access to that material. In Mexico, you don’t. So, nothing. Yes, we met, but no… we didn’t talk about bad things, in my opinion.

[Silvia]: But according to the detention order, she was, and I quote: “Performing the functions of a sheik over the others,”, meaning, a scholar, someone devoted to the study of religion. Something that to Marilú even sounds a little ridiculous.

[Marilú]: I haven’t studied. And the little I have studied are the books I have here.

[Silvia]: So, this was the profile they had made of Marilú after the investigation: a Mexican Muslim, isolated from her community, engaged in studying Islam, and who used the internet to share terrorist propaganda and radicalize other women.

Marilú began her provisional detention on January 24th, 2017, at the prison in Soto Real, north of Madrid. She was there temporarily, less than a month.

[Marilú]: Well, and in Soto, at first, I was overcome with guilt because of my children. I couldn’t sleep because of them.

[Silvia]: Ryane, the oldest, was five, and Adam was two.

[Marilú]: Because I said, “And what would become of them? Are they going to take them to social services? Are they going separate them? How will they live? How long is this going to last?” I thought about a lot of things. I said: “My children are growing up.” And then I thought about Adam, who was the youngest. I said: “They snatched him away from right in the middle of the time when he was growing and forming his personality. They’ve taken them from me.”

[Silvia]: What did you do to keep yourself from falling apart? What did you turn to or?

[Marilú]: I had several… several methods or techniques as I called them. One was inducing a maternal coma. Saying: “You know what? I’m not going to think about this.” Every time I had a thought about them, I pushed it aside. I pushed it aside because I said, “I’m going to fall apart. I’m going to fall apart.”

[Silvia]: She would also write.

[Marilú]: One of the first things I bought when I got to Soto was a notebook and a pen. That was the first thing. After that, I bought water, the phone card and all that, but that was the first thing I bought. And I started writing and writing and writing, everything. From the first day to the last. That was what held me together, a little. And especially, looking at myself: “OK, this is how I am. This is the situation I find myself in. What can I do to improve this feeling?” Because there were days when, man, I cried and cried and cried. And especially because… because I already had the experience of being on the outside and having a someone in my family in prison, which from my point of view is harder, being on the outside rather than on the inside. Because the person who’s on the outside has to take care of what the person on the inside can’t do anymore. So, it was… it was very painful for me to say: “How much must they all be suffering out there?”

[Silvia]: To distract herself, she did what she called “visualization exercises.”

[Marilú]: To do that, you have to learn how to relax. In my case, it’s calming yourself down with breathing. And then trying to see things and relive memories.

[Silvia]: She explained to me how she did it in Ávila, the prison they transferred her to almost a month later, in February of 2017. Compared to the prison in Soto, in Ávila there had a large fenced in yard…

[Marilú]: And there were mountains in the background. So, I would look at them and say… I concentrated on the mountains. I concentrated on the yard, but I didn’t look at the fences, you know? I saw that instead of that fence, well there was a forest. And when it rained, and I could hear the thunder, well, I was in a cabin, which I always liked. It’s been like one of my dreams, you know? Being in a cabin with a chimney, in the rain with the little birds there. So, I imagined that.

[Silvia]: Almost two months after her arrest, she was able to see her kids again.

[Marilú]: I do remember the day they came to see me: March 11th. I do remember that date.

[Silvia]: Her mother —who had traveled from Mexico with her brother— went to visit the prison with the kids. At that time, the kids were with a friend of Marilú’s. She got emotional remembering what it was like to see Adam, the youngest one.

[Marilú]: I didn’t recognize him. I said: “This is the child I left?” He was very tall. And whenever he saw me, Adam —who was the first one I saw— he always came out running with his little arms like this to greet me. And that day, he was there looking at me like: “I know her, but I don’t know who she is”. And it was the same feeling I had with him. I recognize him, but he’s different now. So when I talk to him, I tell him, “Adam, it’s me. Your mother.” Then he recognized my voice and came running to hug me. And Ryane was more reserved. He sat there looking at me. I say: “Don’t worry Ryane, everything is going to be OK. Don’t worry. We’ll be together again. Be strong. Be brave. Everything happens for a reason.” And that was it, and well, saying goodbye is always the painful part. And well then, they left and… and I said I have to give myself another dose of maternal coma to… to not think.

[Silvia]: In the prison at Ávila, Marilú became friends with other Muslim women who were arrested on similar charges. She needed allies in an environment that to her was totally unknown and overwhelming.

[Marilú]: There were times when I didn’t know —along with another girl who’s there for the same thing— we didn’t even know where to hide. They were fighting in the showers. They were fighting in the yard. They were fighting in the TV room. And it was like: “Where do we go?”

[Silvia]: Marilú says that the other inmates sold pills, drugs, among themselves, and she, of course, didn’t participate in that. She didn’t smoke either or buy the alcohol-free beer they sold.

[Marilú]: So, they thought I was weird. They thought I was very weird.

[Silvia]: Again, you didn’t fit in.

[Marilú]: I didn’t fit in. And they started saying: “Oh, she’s the chivata.”

[Silvia]: Chivata, or snitch, as if she was giving the prison officials information about them. But Marilú says that she was only respectful and cordial with them. She came to have heated discussions with the other women in the prison.

[Marilú]: Out of nowhere, they would flip out. On three occasions they were about to hit me.

[Silvia]: But it never came to that.

In October 2017, nine months after her arrest, the prosecution report arrived. It states the charges that she, Aziz, and the other defendants would go to trial for. The prosecutor asks for a sentence of a year and six months for Marilú. But they weren’t accusing her of recruiting and indoctrination anymore. That year and six months was for one crime: “promotion.”

This is Carola García-Calvo.

[Carola García-Calvo]: I’m the senior researcher in global terrorism at El Real Instituto Elcano.

[Silvia]: A think tank for international and strategic studies. I spoke with her because, in the spring of 2017, she published a study analyzing, individually…

[Carola]: The 23 women who up to that point —and since 2013— had been arrested in our country in police operations linked to terrorist organizations of a jihadist nature.

[Silvia]: García-Calvo couldn’t comment on Marilú’s case specifically because it was still open, but I took the opportunity to ask her about the crime of promotion because it’s important in understanding Marilú’s case.

So, a little context: after the terrorist attacks in Paris in January 2015 that we mentioned in the last episode —against Charlie Hebdo and the kosher supermarket— the Spanish government reformed the penal code. And one article in particular: article 578, which sanctions the “promotion” of terrorism. With this change to this article, disseminating messages or slogans on the internet promoting terrorism became an aggravating circumstance —in other words, the penalty can be higher.

And since then —as Amnesty International noted in a special report on the topic— sentences for promotion under this article leaped in Spain: from 18 in 2015 to 31 in 2017. They aren’t all for promoting international terrorism, of course. In fact, of 117 sentences delivered between 2011 and 2017, only 14 were related to groups like Al Qaeda. The majority were about armed Spanish groups that are now inactive or dissolved, like the ETA.

But many of these cases are against social media users, musicians, or journalists.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: This Thursday there was a trial for a journalist accused of promoting terrorism through a number of tweets. The accusation calls for a year and eight months in prison.

[Silvia]: And there are really surprising cases.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: In Spain, the National Court has sentenced a rapper to three years in prison for a song about the emeritus king, Juan Carlos. The court found him guilty of injuries to the Crown. Aside from facing charges for the crime of promoting terrorism and supporting the ETA and other organizations…

[Silvia]: All this has generated a debate in Spain: Where is the line between freedom of expression and promotion?

It’s a fine line. It’s not so easy to classify, but this is how García-Calvo explains it:

[Carola]: The enormous difference is between promotion with a purpose or promotion as an expression of ideas. In other words, the free expression of ideas isn’t what is typified, what this is typified is the promotion of ideas that have an objective.

[Silvia]: In other words, motivating or calling for others to commit a terrorist act.

[Carola]: An individual using social media to disseminate propaganda and promote a terrorist organization to incite other individuals to commit attacks in this global strategy is a kind of criminal act we need to have in mind.

[Silvia]: Because international terrorism —its propaganda, its diffusion— has adapted and now it’s there, on social media. But García-Calvo says that that doesn’t mean that “promotion” should be applied to everything.

[Carola]: I mean, what can’t be done is conflate this kind of… of criminal acts for other kinds of… of acts that are not directed to action but rather, well, to the expression of more or less fortunate ideas, or, more or less, uh… well, in good or bad taste. Which is to each their own… it’s not, it’s not my place to judge.

[Silvia]: So, OK, that’s why Marilú was going to trial, for promotion: allegedly posting content on the internet that supported and encouraged others to commit a terrorist act. Which she denies.

[Marilú]: I haven’t written songs, I haven’t shared documents, or videos, or photos, or… Nothing. I haven’t done anything. I haven’t done anything.

[Silvia]: In December 2017, she was given provisional release after 11 months in prison.

[Marilú]: Let’s see, during the time I was in Ávila, I won’t say I was happy. Right now, I can tell you that I’m not happy. Because the first day I go home after they arrest me, as soon as I walk in the door and see the solitude of a tomb, because the house was empty. It wasn’t how I had left it. Most importantly: my husband and children weren’t there. I said: “Well, being here is the same as being in Ávila, because they’ve taken my people away from me.”

[Silvia]: Aziz he was still under arrest. Her children had to go live in Morocco with their paternal grandparents. And they’re still there because Marilú doesn’t have any way to support them. She doesn’t have a job.

Now she can speak with the kids every day, seeing them on camera. Aziz has eight calls a week, which he splits between Marilú and the kids, sometimes the lawyer. They only last five minutes, and since Marilú doesn’t have good signal in her apartment, she has to go out to speak with him.

[Marilú]: To a certain extent it… it motivates me, you know? Because there are days I don’t want to get out of bed. So, when he calls me, I say: “I’m going out.” At first, I always walked around in circles. Now, it’s… I go out. I sit on a bench in the park, because I don’t have the energy to walk around.

[Silvia]: The day I visited her happened to be a day that Aziz was calling. So we went to the park, to that bench she just mentioned.

[Marilú]: Look, here he is… Hello, how are you?

[Aziz Zaghnane]: Hello.

[Marilú]: Oh, my beautiful boy, how are you?

[Aziz Zaghnane]: Well, and you?

[Marilú]: Alright, here. I’m with Silvia…

[Silvia]: I turned off my recorder to give them privacy, and I took a moment to answer my emails. I only managed to answer a few.

[Marilú]: Five minutes. Between him talking to the kids yesterday, how I’m doing, how he is, how he feels… and that’s it. The five minutes were up.

[Silvia]: Marilú told me that she comes to this park a lot, to sit on this bench, in front of a fountain and read. Without a job, without the kids, without Aziz, the days are long.

[Marilú]: Saturdays and Sundays are the hardest. It’s the hardest part for me. Why? Because Saturday and Sunday are when Aziz was around. He didn’t go to work. We could go out, go do a lot of things. And now seeing myself all alone and seeing everyone going out and all that, I say: “Oh.” It’s a little hard for me. And now the days are getting longer, it’s like… like, I just want the night to come. And then night comes, and I say: I don’t want the night to be over, and I don’t want the day to come. I don’t want the next day. But then I say: “No, the next day has to come because if it doesn’t, well, this will take longer and all that.”

[Silvia]: It’s a complicated kind of waiting: wanting time to pass quickly so the trial arrives, to be closer to being reunited with Aziz, with her children; but at the same time not wanting time to pass, because you don’t know if what comes next is going to be worse than what you’re experiencing now.

That day, there was less than a month until her trial, Aziz’s —who was accused of the crime of collaborating with a terrorist organization— and the other men’s, accused of belonging to Aziz’ group.

So, in June 2018, I went back to Madrid.

How are you?

[Marilú]: Like I’m about to take a very important test. I’ve been waiting since that day, May 5th, 2016…

[Silvia]: When Aziz was arrested.

[Marilú]: And then since January 24th, 2017, with more anxiety about what would happen to me. So, well, that’s it. We’ll see what happens to me.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after the break.

[Ad]: This message comes from NPR sponsor, Squarespace. Squarespace allows small businesses to design and build their own websites using customizable layouts, and features including e-commerce functionality and mobile editing. Squarespace also offers built-in search engine optimization to help you develop an online presence. Go to Squarespace.com/NPR for a free trial, and when you’re ready to launch, use the offer code NPR to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain.

[Up First]: Before you can start your day, you’d like to know what’s happening in the news. That’s what Up First is for. It’s the morning news podcast from NPR. The news you need to take on the day in just about 10 minutes. Listen to Up First every morning from Monday to Friday.

[Planet Money]: The economy is hard to understand, but not with Planet Money. We’re like your guide to business and the economy, but fun. Planet Money: look for us wherever you get your podcasts.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón Before the break, Marilú was about to go to trial for terrorism charges.

Silvia was there, and she’ll continue the story.

[Silvia]: In the morning on June 18th, 2018, I met Marilú at a metro station, and we walked toward the National Court.

Perhaps you’ve heard this court mentioned in news stories about corrupt politicians or soccer players with tax scandals. It’s a court that has jurisdiction throughout Spain, and they hear cases on drug trafficking, organized crime, crimes against the Crown, financial crimes, and, of course, terrorism.

Oh, well, Aziz’ brother who lives in the Netherlands went with Marilú. He had traveled to be at the trial. Remember the most serious charges were against Aziz.

[Marilú]: I think he’ll surely already be here, but… he’s at the jail. So I don’t know. I don’t think I’ll be able to see him before.

[Silvia]: She was wearing pants and a white blouse, no veil. She hasn’t worn it since she was arrested. It was obvious that Marilú was nervous. Not just because of how the trial could go, but also because of what it meant to have gotten here after so much time. And to see Aziz.

[Marilú]: It’s going to be the first week in two years that I’ll see him every day. You have to look at the bright side. And that’s it. We’re going to cross here.

[Silvia]: We entered the National Court before ten in the morning. We went through security, we showed our IDs and went down to where the courtrooms are, where they hold the trials. We sat waiting on a cold, metal bench, in a wide hallway outside of the courtrooms. Everything was gray, with no windows, in a basement. The light was white. On a bench near us, were two others who were accused in the same case. They were on provisional release, like Marilú. She says she doesn’t know them. And they had their own lawyer, a different one from Marilú and Aziz’.

After 11, Marilú’s lawyer —Jacobo Teijelo— took her aside to tell her that the prosecutor was offering them all a deal if they plead guilty. It would reduce their sentences, and they wouldn’t need to go to trial.

Jacobo, the lawyer, then explained to me that’s common for them to offer deals like that.

[Jacobo Teijelo]: The deals, aren’t like in other countries, between equals, based in facts, but rather a lot of the time —the majority of the time— people agree to the deals to avoid the risk of a trial in which you’re not sure if the evidence will be judged with due objectivity.

[Silvia]: The other defendants accepted the agreement. But Marilú rejected it outright.

When she sat back down at my side, after speaking with Jacobo, she looked upset. “They already tore apart my life,” she said. She wasn’t going to accept a deal, she said, because that would be admitting guilt, and she hadn’t done anything.

After this, we finally went into the room.

[President of the Court]: This session is open, and let it be known the hearing is public…

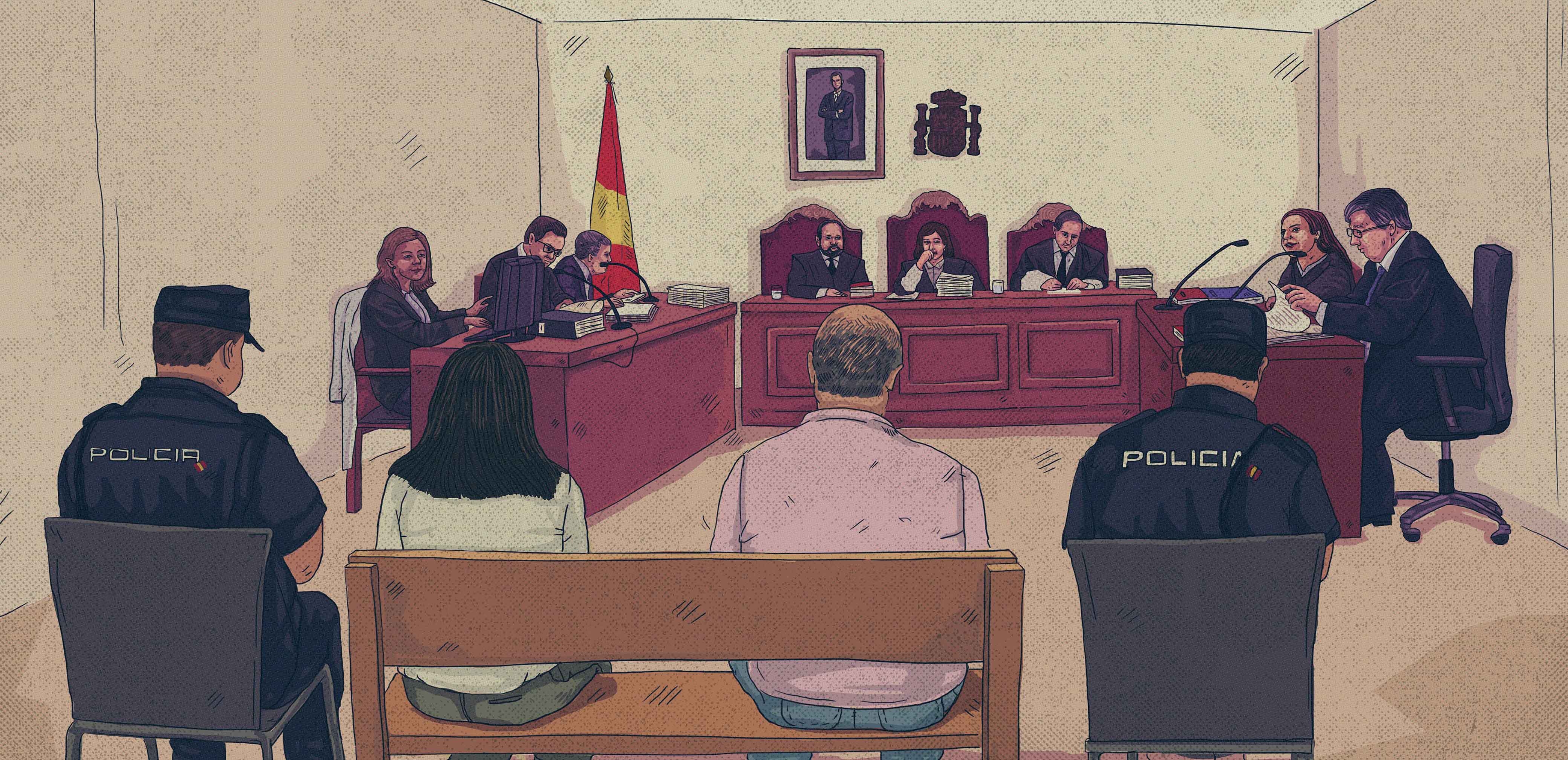

[Silvia]: This is the scene: there are long tables in the shape of an inverted “U.” On the back wall, there’s a picture of the king. At the head of the inverted “U,” there are three judges sitting, in black robes. One of them is the President of the Court, who directs the trial. On the left side, there are the lawyers and someone taking notes on a computer. And at the table on the right is the prosecutor and an interpreter, since some of the defendants don’t have full command of Spanish.

In front of them are the defendants. Marilú and Aziz are sitting on the same bench, but separated, with a space between them. Aziz is wearing jeans and a pink polo. Next to each of them, there’s a police officer sitting on a chair. Aziz’ brother and I are a few rows behind them.

[President of the Court]: Do you acknowledge the facts? If you don’t understand something I say, we’ll translate it.

[Defendant]: Yes, yes, yes.

[President of the Court]: Yes, he acknowledges the facts.

[Silvia]: First, the two defendants who were outside waiting with us, and another who came in with Aziz —because he was also arrested— acknowledged the facts and accepted the charges and the penalties. The President of the Court then says that for them the trial has ended, and they can go.

[President of the Court]: Well then, the two that are here, that have already been indicated, you may… if you want to leave. Not the one who is deprived of liberty, the other two can leave if you like.

[Silvia]: It’s important to remember this detail: they were accused of belonging to a group that Aziz led, but if they left the courtroom —if the trial was over for them— they weren’t going to testify about their relationship with Aziz anymore.

After the three defendants leave, Jacobo —their lawyer— starts asking Aziz questions, all related to the accusations against him.

[Jacobo]: You know why you’re here, correct?

[Aziz]: Yes.

[Jacobo]: Well, uh… the questioning… we could say, is in three parts: on the one hand, how you got here, on the other, the handling of the internet, and then your relationship with the others. Beginning with the first part, are you… are you a fundamentalist. Where do you come from?

[Aziz]: No, I’m not a fundamentalist.

[Silvia]: You can’t hear it very well, but Aziz denies being a fundamentalist, in other words, someone who promotes orthodox Islam. He emphasizes that he’s from Morocco, that since he arrived in Spain, he’s started a family and has tried to integrate into the country, the society. When he talks about his work, he says that he works with women and even his boss was a woman, that he had Jewish clients. Then, about his activity on Facebook, they concentrate on one thread in particular, a conversation about the origin of the Islamic State.

[Aziz]: In the end, it says, “I don’t see it as coherent.” That is, responding to what I said before. Because I have a very clear and defined position against terrorist groups and in particular the group…

[Silvia]: Again, you can’t make it out very clearly from the audio quality, but he’s going into a long explanation about what’s being debated on that Facebook thread. His argument is that his comments are criticizing the Islamic State, not supporting it. Then there are more questions like this one. In total, this part lasted more than half an hour.

[Jacobo]: There are no more questions.

[Silvia]: It’s impossible for us to go through each one here.

[President of the Court]: You may now be seated in the back.

[Aziz]: Thank you, your honor.

[President of the Court]: Ana Marilú.

[Silvia]: So we’re going to continue with Marilú.

[President of the Court]: Do you want to answer the questions posed by the prosecutor?

[Marilú]: No.

[President of the Court]: And your defense?

[Marilú]: Yes.

[Silvia]: She says a lot of things we’ve mentioned before and explains, for example, that she wasn’t isolated. She denies trying to “recruit” people on the internet. She says of some of the images mentioned in the investigation —which they say were taken from her computer— that it’s the first time she’s seen them.

[Marilú]: I didn’t post anything at all. I don’t share those ideologies. I didn’t share those images. On the contrary, I’m a person who always looks for the positive side of everything…

[Silvia]: Marilú’s turn is over, and the trial is done for the day.

[President of the Court]: Tomorrow at ten in the morning we will continue the trial.

[Silvia]: Aziz and Marilú hug. And then some police took him back to jail in handcuffs.

[Jacobo]: Man, I see that they have… that Marilú and her husband are absolutely right. It’s true. They’ve given a very clear explanation of everything. It’s… it’s a coherent situation.

[Silvia]: I went to Jacobo’s office after the first day of the trial to ask him some questions about the case.

[Jacobo]: It’s another thing to see it without… considering it all with suspicion. In other words, look at it with prejudice against them and logically it all looks bad for them.

[Silvia]: This isn’t the first time Jacobo has defended someone accused of terrorism. He defended, among others, part of a group of 11 Pakistani’s who were arrested in 2008. They were accused of planning a terrorist attack on the Barcelona metro. They were convicted of belonging to a terrorist group. Then, the Supreme Court reduced the sentence for some of them and absolved two.

And he’s also worked in other even more high-profile and much more controversial cases. For example, in Spain, several people were accused of being collaborators in the September 11th attacks in New York.

[Jacobo]: I defended one of them.

[Silvia]: Abu Dahdah. He was accused of participating in the conspiracy. He was sentenced to 27 years in prison in 2005. The next year, the Supreme Court absolved him of the crime of conspiracy and lowered the sentence to 12 years.

So, Jacobo is someone who knows very well how the Spanish justice system treats these cases. And, going back to Marilú’s case, I wanted to know why they had started this investigation on her husband and her. Jacobo explained that even he didn’t know.

[Jacobo]: Well, in Spain we don’t have like in the United States discovery, disclosure. In other words, the right to demand that all of the true origins of the investigation be revealed, and we have to go off of hypotheses.

[Silvia]: I’m not going to go into the hypotheses, because they’re just that: hypotheses. The Spanish authorities haven’t explained why they opened an investigation into Aziz.

[Jacobo]: No, because they haven’t given any explanation. They say we were, as they say, patrolling. As they ironically say here: patrolling the internet and, well, we saw this man with a profile that made us suspicious.

[Silvia]: A very general explanation. But aside from what started this investigation, for Jacobo, in this case…

[Jacobo]: In the end, what’s at stake here is freedom of expression. If someone has a picture of an Islamic State flag it could be to say that it’s good, it could say that it’s bad, or something else, or it could even be an accident. I mean, it could happen to anyone.

[Silvia]: Aziz and Marilú’s trial went on for two more days. The second day the agents who worked on the investigation and expert witnesses gave statements.

The prosecutor was the first to ask questions.

[Prosecutor]: Well, can you tell us, in relation to the investigation, when, why, and how did it start?

[Agent]: Yes, it started in 2014…

[Silvia]: The first agent explains that they started investigating Aziz in 2014 That they patrol social media profiles and that an open Facebook profile, run by Aziz, caught their attention. The agent says that the administrator —Aziz— posted explicit content that incited people to die as martyrs, for example, or images of jihadists.

[Agent]: Another fact that caught her attention was that elevated number of friends it had. It had almost three thousand friends…

[Silvia]: It stood out to them that he had so many friends, almost three thousand he says.

[Prosecutor]: That profile, did he administrate it himself or was it… or could you come to the conclusion that some other person used it?

[Agent]: Well, we have come to the conclusion that it was used interchangeably by Aziz Zaghnane and his wife.

[Silvia]: And according to this agent’s statement, Marilú also accessed that profile.

The agent says that he learned Aziz’ work schedule: who he met with —another one of the defendants, for example— when he went to the mosque, how often and who he went to the gym with.

They also listened to telephone calls. And all this brought them to the conclusion that Aziz led a group of radicalized Muslims and that he also had a lot of influence at the mosque in Pinto.

Jacobo questioned these and other accusations.

[Jacobo]: And tell me, how is it possible that you say he is a sheik, that is, a learned man, and on the other hand that he doesn’t know. Does he know or doesn’t he?

[Agent]: He knows more than those around him.

[Silvia]: He knows more than those around him, the agent says.

Aziz’ brother, who again was sitting next to me, shook his head occasionally, as if to say: “This is ridiculous,” or murmured: “That’s not true.” With one accusation in particular —that an agent had heard Aziz on the phone saying that Osama Bin Laden appeared to him in a dream— he laughed and said it was nonsense.

Marilú and Aziz sometimes looked at each other and shook their heads, as if to say: “I can’t believe this.”

On the third and last day, they showed videos they had found on Aziz’ computer. Some were very explicit. A woman translated them and explained what they were about. Then, in the end, the prosecutor summarized the accusations against Aziz and Marilú.

[Prosecutor]: The first defendant stands accused of this crime, as we have said, of indoctrination, and Marilú is… uh, is accused solely of the crime of promotion.

[Silvia]: And she says that Marilú’s conduct is not restricted to freedom of expression.

[Prosecutor]: She does not limit… she does not limit herself to having these ideas herself, or to keeping this material which may or may not have a jihadist or violent character, but instead, she extols it and publishes. And that is where we enter in the dynamic, or in the controversy, between if this is about freedom of expression or if this is about promotion.

[Silvia]: Her statements lasted 15 minutes. Then Jacobo speaks for almost half an hour, questioning the accusations and the agents that testified. And several times he goes back to the topic of freedom of expression.

[Jacobo]: Freedom of expression is under question, of course it is, she is being prevented from thinking.

[Silvia]: In the end, the President of the Court gives Aziz and Marilú the opportunity to have the last word. Aziz doesn’t speak, but Marilú does…

[President of the Court]: Yes, in that case please take a seat in front, please, so you can be recorded, if you want to say something else.

[Silvia]: Marilú stands up and sits in the seat where she had answered Jacobo’s questions about the accusations against her two days ago. She starts to speak.

[President of the Court]: You may speak.

[Marilú]: All I want to do with this proceeding is to heal myself (inaudible). Free myself because…

[Silvia]: She says the only thing she wants to do with this proceeding is to heal herself, free herself, but she gets emotional, and it’s hard for her to continue.

[President of the Court]: Alright, calm down. Calm down.

[Marilú]: It’s just that, since this started, on May 3rd, 2016…

[Silvia]: Marilú explains how traumatic Aziz’ arrest was and how hard what came after was. The President of the court interrupts her and explains that she is giving her the right to the last word in order to add something that she considers relevant to her own defense that her lawyer has not said.

[President of the Court]: That’s what it’s for.

[Marilú]: Of course, yes, excuse me.

[President of the Court]: Alright, it’s not important, but concentrate on that.

[Marilú]: I have to take out everything I have to… because today a new life is starting for me. This chapter is over now…

[Silvia]: Marilú says that with this trial she’s closing a chapter, that she had learned techniques to help others.

[President of the Court]: Very well. Specifically, with regards to your defense, do you want to say anything else or is what your lawyer has said enough?

[Marilú]: No.

[President of the Court]: Alright, well I move for sentencing.

[Silvia]: Well, today was the last day of the trial, how are you?

[Marilú]: Well, better than before. I’m more hopeful after having heard and experienced everything that was said. Really, there’s absolutely nothing. So I hope that all of this is favorable and that now… this chapter has closed for good and we can just be left with what’s good.

[Silvia]: Marilú wants to write a book about her experience, even though she’s afraid that what she writes will get her accused of something.

[Marilú]: To some, I will be inno… innocent, and they’ll know that an injustice was committed, but to others, I will always be guilty of something I didn’t do.

[Silvia]: On June of 2018, her sentence was released. Aziz was sentenced to the crime of, I quote, “active terrorist indoctrination,” and they gave him six years in prison. Marilú was sentenced to a year in prison for promoting terrorism. She didn’t go back to prison, because of time served, but Aziz had to continue serving his sentence.

They appealed the sentence with what’s called a cessation appeal. In November of 2018 a prosecutor for the Supreme Court said that the sentence against Marilú and her husband should be repealed and that they should hold a new trial because, basically, the first one was done wrong. It violated her fundamental right to a process with all guarantees.

Why? Well, the prosecutor’s response is written in complex legal language, but, in short, it all revolves around the President of the Court’s decision to remove the other three defendants that did accept the deal. With that, they weren’t questioned about Aziz and Marilú. And the prosecutor explains that even though part of the defendants reached a plea agreement, they still had to conduct the trial with all of the defendants in a case like this one. Besides, the prosecutor says there are contradictions in the sentences of those who accepted a plea deal and those of Aziz and Marilú.

In February of 2019, the Supreme Court canceled the sentence and ordered that the trial be repeated with a different court. Aziz was released on parole on March 14th. At the time we released this episode a new date for the trial had not been announced. For now, Marilú and Aziz are making plans to reunite with their children.

[Daniel]: Silvia Viñas is an editor and producer for Radio Ambulante. She lives in London.

This story was edited by Camila Segura and by me. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano. Ana Prieto did the fact-checking. Thanks to our editorial assistant, Victoria Estrada, for her help on this episode.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Andrea López Cruzado, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Luis Fernando Vargas, and Joseph Zárate. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Do you follow us on Instagram? We want to follow you back. In your stories, post a video of you listening to Radio Ambulante or recommending the podcast to your friends, and tag us under @radioambulante. Today we’re following back accounts that mention us. Remember: @radioambulante on Instagram. Thanks!

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.