Translation – J vs. United States

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: This episode of Radio Ambulante includes descriptions of sexual situations that may be impactful, and it is suitable for adults only.

Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

[Silvia]: Introduce yourself. My name is…

[Gloria]: OK. My name is Gloria, and I’m the mother of the girls who were affected.

[Daniel]: That’s not her name, but that’s what we’re going to call her to protect her identity. Later on, you’ll understand why.

[Silvia]: Where are you from?

[Gloria]: Well, I’m from a village in Guatemala.

[Silvia]: What’s your village like?

[Gloria]: It’s small and mostly agricultural.

[Silvia]: Gloria arrived in the United States about 13 years ago.

[Daniel]: In March of 2018, our editor, Silvia Viñas, traveled to central California —near Fresno— to meet Gloria.

[Silvia]: She has two daughters and when she left Guatemala, they were little, one was seven and the other was four.

[Daniel]: We’ll call them Clarita and J —also to protect their identities.

[Silvia]: What was it like for you to come here? Was it easy to adapt or…?

[Gloria]: Early on no. Because first, I’m a mother, I missed my daughters a lot. Wherever I went, well, they were always on my mind. But when I started getting my first paychecks and I could see who I was giving them a different life than what I gave them over there, I started to… I was cheering myself on and saying: “No, the more… the more I work, the more my daughters will have.”

[Daniel]: Gloria, like a lot of parents in her position, sent her daughters money.

[Silvia]: And in that way, she was carrying out, more or less, the plan she had when she left: work in the United States for a few years, send money to her daughters, save, and then go back. I say ‘more or less’ because one year turned into two, then three, then four, then ten, and Gloria ended up staying. Clarita and J grew up in Guatemala with relatives, mostly with an aunt. But they talked with Gloria all the time.

[Gloria]: Sometimes we would speak like 15 times a day: “What are you doing? What are you going to eat? Where are you going?” I would tell them: “The day you feel like… like you’re being smothered by me, tell me, and I’ll understand.” And they told me: “No, mom, we like it when you ask us things because we know that someone is there for us.” And now that the times have modernized, we can video chat. And, well, things changed.

[Silvia]: In other words, they had a close relationship despite being far away.

[Gloria]: Very close.

[Silvia]: In 2016, during one of those calls, Clarita and J —now 19 and 17— told Gloria that they wanted to go to the US.

[Gloria]: And I didn’t want them to. I said no.

[Silvia]: It’s not that she didn’t want to see them, she was afraid of the path they would have to take to get there.

[Daniel]: Which is understandable, isn’t it? Gloria had made the journey, she knew what it was like. And she knew it was getting more and more dangerous, especially for two young girls traveling alone. There are kidnapping, extortions, rapes.

[Gloria]: A lot of things happen there, and many people even lose their lives. And I wouldn’t have wanted to sacrifice for so long so that something would happen to those I loved most in my life.

[Silvia]: But they wanted to go because Gloria was about to have an operation. They wanted to be with her to take care of her. On top of that, not long ago a 15-year-old girl who lived on their block had been kidnapped in their village. The kidnappers asked for money, but the girls family didn’t have any. Gloria says that in the end she was returned four or five days later: alive, but a little traumatized, of course. Clarita and J were afraid the same thing would happen to them.

One day —in July of 2016— Gloria called her sister’s house, where the girls lived and asked to speak to them.

[Gloria]: “They went to Mazate,” my sister told me.

[Daniel]: To Mazate. Or Mazatenango, a city in southeastern Guatemala.

[Silvia]: That seemed normal to Gloria. Some relatives lived there, so it was common for them to go visit. So they kept talking.

[Gloria]: But later she said: “I can’t lie to you. What do you think?” “What?” “Your daughters left.”

[Daniel]: “Your daughters left,” she told her.

[Silvia]: Gloria knew what her sister meant by that: Clarita and J had left, headed for the US.

[Gloria]: I asked my sister if she was sure: “They… they didn’t go… go to see family in the capital?” “No,” she told me. “They don’t keep anything from me, but they just told me not… not to tell you so soon.”

[Silvia]: Gloria went four days without hearing from her daughters. Four days of hell. She went to work in the fields, harvesting fruit, and they were all she could think about. Where they were, how they were. Until finally, they called her. They were in Mexico.

[Gloria]: When they called me and told me: “We’re sorry, but this is for you.” I couldn’t say: “No! Go back!” I said: “It’s your decision.” I said, “Well, I wish… wish you all… all the luck in the world.” And then I waited to see what… what happened.

[Silvia]: Three days later, a Customs and Border Protection agent called her.

[Daniel]: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, in English, or CBP by its initials. It’s the agency that patrols the border —the agents that detain people who try to come into the country without papers.

[Silvia]: So, this agent who called Gloria…

[Gloria]: Spoke to me and said: “I have your daughters here.”

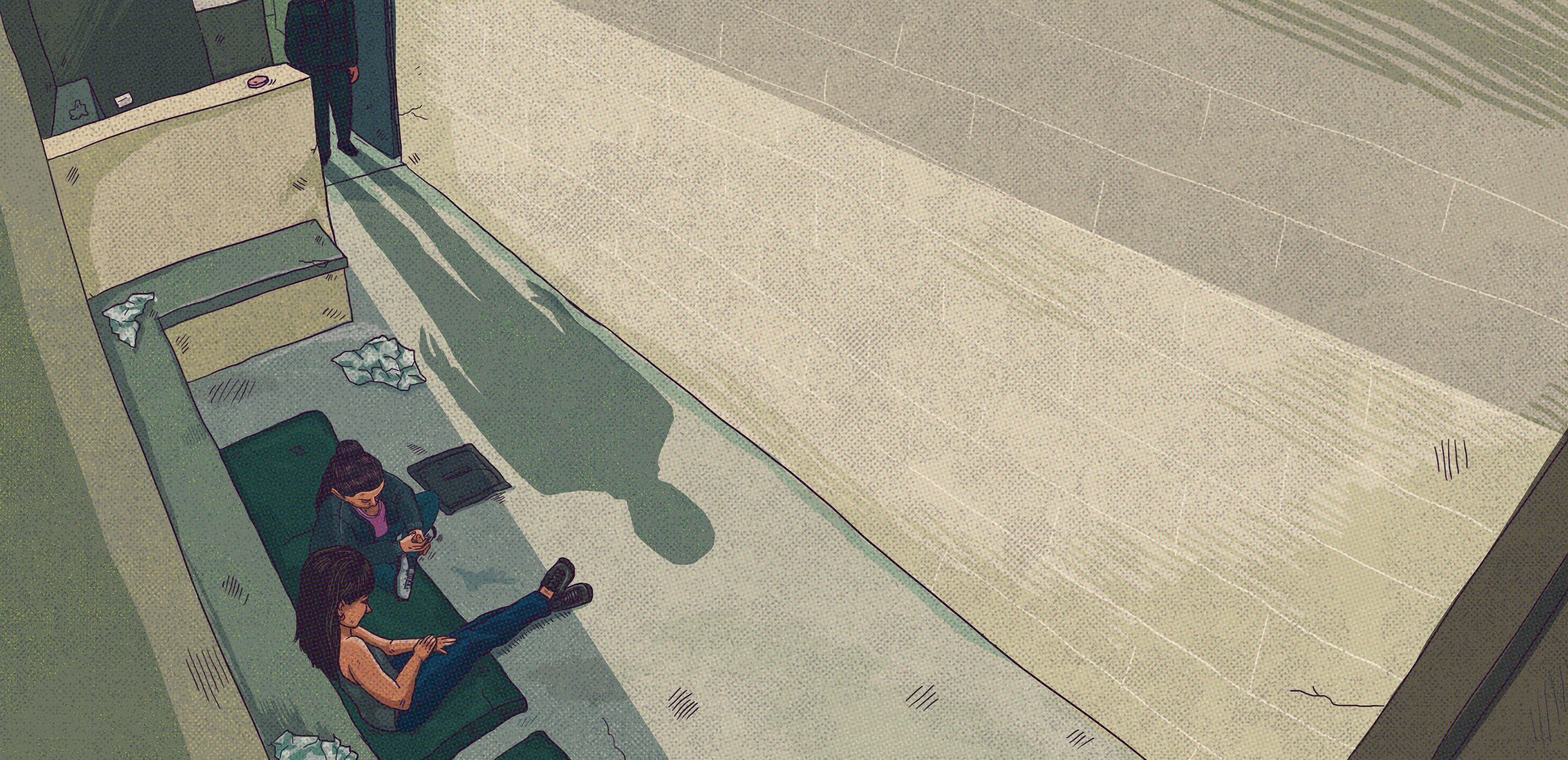

[Silvia]: They were at a border patrol station in a small town called Presidio. It’s in western Texas and it has a little over 4.000 residents. And the CBP station in Presidio works as a temporary detention center —with three cells— where they hold undocumented immigrants for 12 or 24 hours, a few days at most.

[Daniel]: In this type of station, they “process” immigrants, in other words, they take down their information, they take their fingerprints.

[Silvia]: When Gloria heard that her daughters were there, that they were OK…

[Gloria]: I wanted to cry with joy, but I said: “No, he won’t have time to listen to me cry,” right? “I will on my own time,” I said.” And I always say: “I have to be strong.” And I tell him, “Oh, good,” and everything. I’m… I’m really happy. And he says: “I’ll let you talk to… to one of them but quickly.” And then I heard they were crying, but I mistook that: they were crying with joy.

[Silvia]: Because they were safe because they were talking to her because there was a chance they would see each other soon. Gloria says the call didn’t last very long, a minute. But she already felt much calmer. Her daughters were OK.

A few days later another agent called.

[Gloria]: He introduced himself as an… an investigator, and he asked me… uh… calmly, if I knew what was going on. If my daughters had told me. And I said: “No, my daughters haven’t… haven’t had much of a chance to speak with me.” And then he said: “Ma’am, please stay calm. I’m going to tell you what’s going on.”

[Silvia]: But first, he asked her:

[Gloria]: “How well do you know your daughters?” “Look,” I said to him, “First of all, I think a mother never speaks ill of her daughters and a mother in the depths of her heart —whatever the case may be— knows what kind of children she has, even though she may not say it. Why are you asking me that question?” I said. “This what they’re going through: they were abused and we’re investigating it.”

[Silvia]: Clarita and J had reported that an agent had sexually abused them. The same agent who had called Gloria a few days earlier. The investigator told her…

[Gloria]: “But rest assured we are going to help you.” And I broke into tears. I started crying, and I said: “But why have they…they have…” I thought… thought back to when… when I heard them crying, but I mistook their tears.

[Daniel]: Silvia has been following this case for more than a year, trying to understand what happened at that border patrol station in Texas and what this incident tells us about the largest security agency in the United States.

Here’s Silvia.

[Silvia]: Before traveling to California, I had been in contact with Gloria, Clarita, and J over WhatsApp.

[Gloria]: Hello.

[Silvia]: Hello, how are you? I’m Silvia Viñas.

[Gloria]: Oh, yes. Well, thank God. How are you?

[Silvia]: Fine, thank you. I’m calling you from….

I had spoken with Gloria over the phone while the sisters listened on speaker. I had explained that I wanted to spend time with them, get to know them. Beyond them telling me what happened at Presidio —the details of the abuse they had reported— I wanted to know about them: what they liked to do, how they were adjusting to their new life in the United States, to living with their mom after growing up away from her.

They accepted and I got ready for my trip. But a few days before I went, Gloria let me know that Clarita and J didn’t want me to interview them anymore.

You can imagine the panic I felt. But I decided to go anyway, thinking that maybe they would change their minds, that somehow the opportunity would present itself.

Gloria did want to talk. She told me that she felt like she needed to tell people about her experience: how she had experienced all this as a mother. A kind of catharsis. I interviewed her and I was also able to interview the sisters’ lawyer.

[Angélica Salceda]: Angélica Salceda, an attorney with the ACLU.

[Silvia]: “ACLU,” American Civil Liberties Union or ACLU, as they say in English.

[Angélica]: The ACLU is an organization that aims to defend the rights of… uh…. everyone here in the United States.

[Silvia]: Their lawyers, like Angélica, focus on cases involving the right to privacy, voting access, the rights of LGBT people or immigrants.

Angélica learned about the abuse the two sisters had reported from an email. Someone who had met Gloria and learned her story wrote to her. Angélica was interested right away. The ACLU had been investigating abuse by immigration agents against minors, like J.

[Angélica]: So we already had an idea of the kind of abuses that existed and still exist. So seeing two girls in front of me with this possible story, obviously I was outraged, right? Knowing that people who are only looking for safety, tranquility, and peace in their lives and that are traveling to the United States —which is very difficult and requires a lot of strength— have been treated this way.

[Silvia]: So she took the case. She met Clarita, J, and Gloria. And heard their story.

After speaking with Angélica and Gloria, it was clear to me that I wasn’t going to be able to interview the sisters on that trip. And I didn’t want to force it either, obviously. It’s very delicate. I didn’t have anything proving that they had been sexually abused. But, if they had been? I didn’t want their talking to me to affect them, to make them relive a traumatic event.

So Gloria told me a little about them.

[Gloria]: Well, Clarita is kind of like… reserved. She always has been, since she was little. She just looks and thinks and then she… she says something. Yes, she’ll chat, but she has to build trust with that person.

[Silvia]: And her sister J.

[Gloria]: The younger one is more direct, and she’ll start talking. She’s not super talkative, you know? But yes… they… they are different. One thing they do share is they… they go to church together, they do that.

[Silvia]: She told me they have a lot of faith. Something I noticed over WhatsApp. Their profile pictures change from time to time, and sometimes it was a religious quote or a verse from the Bible.

In my last days in California, I got a message from Clarita over WhatsApp. I wasn’t expecting it. In the text, she said she was sorry for not giving me an interview. She says she hopes I understand and she thanks me for the opportunity. I quote:

“The reason I don’t want to give more information about the case is that every time I’m interviewed, I remember what happened and it’s still painful and sad.”

So, what you’re going to hear now comes from what I’ve been able to reconstruct from my interviews with Angélica and Gloria and reading the legal documents that have been published about the case. And from this audio:

[Voice]: Good day, and welcome to the CBP misconduct press call…

[Silvia]: A call that the ACLU organized for the media in March of 2017.

[Voice]: Thank you for joining us for today’s media call. The ACLU of Northern California filed today two administrative claims on behalf of two teenage sisters.

[Silvia]: That month, the ACLU —representing Clarita and J— filed an administrative claim against CBP. It’s a kind of complaint that is made directly against an agency, rather than before a judge. If it’s settled with the agency —be it CBP or another— then the case doesn’t have to go to trial. It’s to avoid saturating the courts that already have a lot of cases.

Well, on this call Clarita gave her version of what happened at Presidio. She starts by saying why she left Guatemala with her sister.

[Clarita]: I left Guatemala for the United States looking for safety, stability, and to be with my mother who’s here in the US.

[Silvia]: They arrived at the US-Mexico border on July 11th, 2016. As we’ve already said, she was 19 and J was 17. They had traveled by bus, from Guatemala for nearly a week. They came alone, without a coyote. They made it to Ojinaga, a border town in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. On the other side was Presidio, Texas.

[Angélica]: When they got there, they were ready to enter the United States, not knowing how, not knowing where they were.

[Silvia]: There they met a young man who told them he was underage. And he joined them to cross together.

[Angélica]: So they crossed the border and they start walking. I mean, they… they didn’t know where they were going, they just started walking.

[Silvia]: It was nighttime. They were lost, scared, and very thirsty. Clarita says they saw a patrol car go by and asked for help, but they didn’t hear them. After some time, another patrol car passed.

[Clarita]: We asked for help again. They stopped. Two agents came out of that Border… border patrol car.

[Angélica]: Well, they asked them questions: how old they were, if they were immigrants, where they were from. So they thought it was normal, right?

[Clarita]: They searched us properly. They asked us if we were carrying something… if… anything that could cause them harm. We told them no.

[Angélica]: They took their backpack, put them in the vehicle and brought them to that detention center in Presidio.

[Silvia]: To the border patrol center.

The agents asked them to take off their shoes and put them in a cell together. They put the other boy in one of the other cells. In the third cell, there were other detained persons.

Those two agents went to keep patrolling, and they left another agent —who we’ll call Agent F— alone, in charge of the detainees. In other words, of Clarita, J, and the other immigrants.

And, according to the sisters, Agent F…

[Angélica]: Asked the older sister, first, to get out of her cell and come with him to a… a small room.

[Clarita]: He led me to… to a room where there was food.

[Angélica]: Because there were potato chips, there were different kinds of food.

[Clarita]: He told me he was going to do a security check on me because it was his job.

[Angélica]: He stood in front of the door, like, to block it.

[Clarita]: Then he told me to take off my sweater because he was going to do a security check on me. I took off my sweater. Then he told me to take off my blouse. And I asked him: “Why?”

[Angélica]: She asked… the… the older sister asked for an explanation. Why? What was the reason?

[Clarita]: Again he told me it was for security.

[Angélica]: He had to make sure she didn’t have anything on her person, and… and… uh… so she had to. She had no other option.

[Silvia]: She had to take off her blouse.

[Angélica]: And he also asked her to take off her bra as well. A young girl… 18 or 19 years old, for example, who looks much, much, much younger. Obviously, she asked him again if it was necessary, what was the reason. And he… he kept on insisting.

[Clarita]: I just undid it… I just undid it so he could see that I wasn’t carrying anything under the… the bra. And then he lifted the bra and started touching my breasts.

[Silvia]: Clarita says that Agent F asked her to take off all of her clothes, all of them. Clarita reiterates that the agent told her it was for security.

[Clarita]: And… he started to touch my private parts. Then he told me… after that he… he told me to get dressed. I got dressed and left the room crying because of how bad I felt.

[Angélica]: And then he walked her back to the cell.

[Clarita]: I went… went to the cell where my sister was. Then he took my sister. Sadly, I never thought he would do the same thing to my sister, because she was a child… (crying) that maybe he did it to me because I was an adult.

[Angélica]: Well, the same thing happened to the younger sister. The officer took her to the same room, and it was almost the same, right? Asking her to… to take off her clothes, her upper garments, and her lower garments as well, and he also… he also touched her.

[Clarita]: Later, my sister came to the cell where I was. She came crying. And I asked her what that man had done to her. She didn’t answer. She just cried and looked at the ceiling. And she… she didn’t say anything.

[Angélica]: Her face was expressionless. She didn’t want to talk. Clarita asked her to tell her what had happened, but no, the younger sister wouldn’t tell her. Then Clarita told her younger sister what had happened to her.

[Clarita]: All she said to me was: “I don’t know if he did his job the right way or if that was his job.” And that’s what my sister said to me crying.

[Angélica]: So the two stayed in the cell just crying.

[Clarita]: We cried a lot. We felt a lot of pain, a lot of fear, a lot of sadness over what had happened (crying). The man was very nervous. He told us to be quiet, to not cry, to calm down and that he was doing his job. He gave us food so we would be quiet, so we wouldn’t cry.

[Angélica]: He offered them chips, Sabritas, and he also told them that if they didn’t say what had happened, he would let the older one pass as a minor.

[Silvia]: Because if both of them were minors, they could go to the upcoming immigration process together. It was easier for minors to stay in the United States. But Angélica said they refused the offer.

They couldn’t stop crying. The agent offered to put them in contact with their mom. At that point, Gloria didn’t know where they were.

[Clarita]: He called her and put her on speaker.

[Angélica]: To make sure he… he could hear everything.

[Clarita]: We spoke with our mom, but then he hung up. He didn’t let us tell our mom anything else. He just let us tell her that we had been arrested and that we were OK.

[Silvia]: This is the call that Gloria was referring to at the start of the episode, when she heard them crying and thought it was because they were excited that they would be together soon. The call when she thought her daughters were OK.

According to the two sisters, once he hung up, Agent F took them to a computer to ask them for their information so he could continue processing them. He started preparing to take their fingerprints digitally.

That was when the other two agents came back, the ones that had brought them to the station and had been away when the abuse that Clarita and J reported took place. They came with a few men, other immigrants they had detained.

[Angélica]: So at that moment, the girls were talking to each other, they said to one another that they were going to watch and see if the agents that had come back did the same thing with the new detainees. In other words, if they took the new detainees to that room.

[Silvia]: And they didn’t. They didn’t see anyone take the men to the room to check them as they had taken them. They checked them over their clothes in front of the girls and the other agent. So, when they saw that…

[Angélica]: That was when they got up the courage to say: “No, what happened to us wasn’t right. It was wrong, and we need to tell someone.”

[Silvia]: Agent F took Clarita’s fingerprints and took her picture. Then it was her sister’s turn.

[Angélica]: So while he was taking the younger sister’s fingerprints, the older sister had the courage to go up to one of the two agents that… that had arrested her.

[Clarita]: I went up to him to ask if the agent… the agent that had done that to us —because I pointed at him— had done the right thing.

[Angélica]: That the officer had taken her to that room and made her take off her clothes.

[Clarita]: He was shocked. He said: “What!”

[Angélica]: The officer that she was telling asked her if that had happened to her. Clarita told the officer yes.

[Silvia]: According to legal documents prepared by the ACLU —based on J’s testimony— that agent was surprised and told Clarita that Agent F should not have searched them that way. But the other agent who had detained the accused her with lying and put her in a cell.

When he realized what was happening, Agent F also said that Clarita was lying.

But she had already made the complaint and with that, according to agency protocol, they had to record it. The agents in Presidio reported the complaint to their superiors, and they interrogated the girls separately, without Agent F present.

First was Clarita.

[Clarita]: They told me to describe the place where the officer had taken us.

[Angélica]: And Clarita says that upon giving them the details about that room, the officers had a… uh, a sort of surprised look on their faces, right? They were very surprised that she knew all the details about that… that room.

[Silvia]: Clarita says that one of the agents who was there —while they were being questioned— kept accusing them of lying.

According to legal documents prepared by the ACLU, the agent that questioned them ask J to draw a picture of where the room was. She drew its location with her finger on the table. The document says that after that the agent stopped accusing them of lying.

[Clarita]: And then they told us not to worry, not to be afraid anymore, that they were going to take care of us, that we had to wait because and an investigator was coming.

[Silvia]: They let them sleep there, in the room where they were questioned, instead of the cell.

On the call, Clarita doesn’t say much about what happened when the investigators from the agency arrived. She just said they had to tell them everything again.

On July 14th, 2016 —three days after they were detained— the sisters were allowed to leave the border patrol station in Presidio. They left with something called an “order of supervision.” With that, instead of being deported, they could reunite with Gloria and see how they could regularize their migratory status together.

I asked Gloria what it was like to wait for them to arrive.

[Gloria]: I felt like I was… I don’t know, flying, like my body was made of cotton. I think I felt bad too because… because… because of all the things that had happened.

I took a deep breath and said: “I have to be strong. I’m not going to cry very much.” Because my eyes were very, very puffy from… from crying. Then I said: “I need to be with them right now. I have to… I have to make it look like I’m OK.” Because I wasn’t OK emotionally.

When I saw them, it was like… like… like instead of reaching out… my hands were like this, like I had no strength. And they ran, hugged me, kissed me, and I was like: “These are the little girls I left!”

[Silvia]: Gloria says they looked calm.

[Gloria]: Because they say that they couldn’t handle the excitement of seeing me, and for a moment they forgot what was happening.

The reunion was something that… that only I can understand. It was… I had to be happier than anything else, but I said… no, I… it was hard.

[Silvia]: It was hard to disguise, to pretend that everything was alright. Some relatives had a reunion to welcome them.

[Gloria]: And, uh… I was like gone. Like nothing mattered to me. So someone asked me: “Tía, what’s up with you? You’re not like this.” But only I knew, but I wanted to scream… what I’m feeling, what is happening, but I couldn’t.

[Silvia]: There hadn’t been any time to sit and talk, just the three of them, in peace. The CBP investigator Gloria spoke with over the phone…

[Gloria]: Told me: “They aren’t doing well mentally, and what… what… what I recommend is that you find some way to distract them.” That’s what I said too: “Right. I want to leave this meal so I can talk with them and really talk, not about what happened, but just hold each other and not let go.

[Silvia]: There would be time for that. When the meal ended and they could go home and start a new stage, the three of them together again, after more than a decade. And they opened up to Gloria and told her how they had been affected by what happened in Presidio.

[Gloria]: They told me that at the time they doubted God. They, uh, said: “God, we’ve served you and… why have you abandoned us? Why didn’t you change that man’s mind? Why us?” And I tell them: “God puts… great tests before those who know… those who know they are going to be able to survive and overcome all of this.”

[Silvia]: Clarita ended her testimony on that call in March of 2017 saying that they never imagined something like this could happen to them in the United States.

[Gloria]: It had a big impact on us, psychologically, you could say. At first, we were really afraid. When we got here with my mom, we suffered a lot. We cried every night. We wondered why this had happened. I couldn’t understand.

[Angélica]: They imagined the United States very differently.

[Silvia]: Again, this is Angélica Salceda, their lawyer.

[Angélica]: What I believe they knew about the agency was that it was an agency tasked with protecting the United States, right? But also the people who come through, who cross the border.

[Clarita]: Why would a person who offers safety do this to us? (Crying).

[Silvia]: “Why would a person who offers safety do this to us?” Clarita says.

[Angélica]: I think that was what had the biggest impact on me, right? Seeing them and seeing that shock on their faces, in the way they way they were expressing themselves and how they saw the United States now. In a way that… well, since I’m in this country and I also love this country, I feel very badly that they were treated this way, after having tried to seek peace in their lives.

[Silvia]: You can hear the shock that Angélica mentions in Clarita’s voice. It’s a trauma that she still hasn’t recovered from.

[Clarita]: The fact that we aren’t from this country, that it’s not ours, but please respect us. Because we’re not animals that can be treated this way. Much less a child (sobs) who can’t defend herself.

[Silvia]: Six months later —in September 2017— CBP responded to the administrative claim the ACLU filed saying they denied the accusation due to lack of evidence. In other words, the case wasn’t going to be settled with the agency directly.

Angélica says that for the girls, it was hard to get that response.

[Angélica]: So you can imagine… especially for… for a minor or someone who’s come to this country for the first time thinking: What more evidence do you need? And now we’re in the same place we were before and even worse because this… this happened to us.”

[Silvia]: This answer came a week before the #MeToo movement took off, when The New York Times uncovered the abuses of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, when women all over the world shared their stories of sexual violence and asked the same question: what more evidence is needed?

The accusation that Clarita and J made had come out months before on some media outlets.

[Angélica]: Yes. they had to share their story, but telling it all again in detail, answering questions, not knowing if the reporter is asking you these questions because they don’t believe you either or… or is asking for certain details. I think it was very… very difficult for them.

[Silvia]: In the WhatsApp message Clarita sent me, she told me that people close to her learned about what happened from some interviews they did with other media outlets. Some TV programs tried to hide their identities, but it wasn’t enough, because some people they new recognized them. And Clarita said that some of them made fun of them and humiliated them. And of course, that affected them deeply.

Clarita and J’s voices and those of other immigrant women maybe don’t resonate as much as those of actresses and famous women who told their stories of sexual violence, but in reality, the original #MeToo movement —the one activist Tarana Burke started in 2006— focused on young women like Clarita and J. Their website explains that it’s a movement that seeks to help survivors of sexual violence —especially young women, minorities, and with few resources— to recover.

After CBP’s response to the administrative complaint, Clarita and J had six months to decide what to do: if they should leave their complaint there, closed, or take the case to court in a federal suit.

A few days after my interviewed Angélica, J —the younger sister— had made the decision to bring the suit to federal court. Clarita decided not to, for reasons that Angélica couldn’t comment on.

The suit is against the government, and it names three people: Agent F and the two officials that brought them to the station. There were a lot of questions to answer.

[Angélica]: We don’t know what’s happened to the agent. We don’t know if the agent is still working or not. We don’t know if the agent has done the same thing with someone else.

[Silvia]: With this case, the ACLU intended to clarify these and other questions. But…

[Angélica]: We don’t know if it going to have that resolution, right? Because there’s always… there’s always the possibility that it won’t… won’t be resolved.

[Daniel]: After the break, how common are reports of abuse against CBP agents and officers? How does the agency handle complaints of sexual harassment and abuse? And, what has happened with these sisters’ case?

We’ll be right back.

[Ad]: This message comes from NPR sponsor, Squarespace. Squarespace allows small businesses to design and build their own websites using customizable layouts, and features including e-commerce functionality and mobile editing. Squarespace also offers built-in search engine optimization to help you develop an online presence. Go to Squarespace.com/NPR for a free trial, and when you’re ready to launch, use the offer code NPR to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain.

[TED Radio Hour]: What is unique about the human experience and what do we all have in common? Every week on TED Radio Hour we go on a journey through the big ideas, emotions and discoveries that fill all of us with wonder. Find it on NPR One or wherever you get your podcasts.

[NPR Politics Podcast]: There is so much political news to follow these days. But you don’t have to keep with all of it, you just have to keep up with the NPR Politics Podcast. You can find it on the NPR One or wherever you listen to podcasts.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante, I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, we heard about the case of two Guatemalan sisters —one of them a minor— who had reported that a border patrol agent had sexually abused them.

We wanted to know if cases like this one are isolated incidents or if it’s an example of how the largest security organization in the United States has discipline problems with its agents.

Silvia continues the story.

[Silvia]: I requested several interviews with officials from CBP —like Matthew Klein, the head of the professional responsibility office, where they investigate reports of corruption and misconduct with their employees— but they told me that Klein wasn’t available to speak with me. The same thing happened when I asked to speak with other officials. So, I looked for other sources.

[James Tomsheck]: My name is James Tomsheck. I am retired from a 40-year career in law enforcement.

[Silvia]: Like him, James Tomsheck. He was in charge of the CBP department of internal affairs from 2006 to 2014. He retired from the agency when they removed him from his position in internal affairs. He has spoken to several media outlets about his experience in the agency, and is considered a whistleblower. I told him that CBP had rejected my requests for an interview, that they weren’t responding to my requests for public information with the reports I was asking for and I asked him:

Why is the agency so secretive?

Why did the agency seem to have so little transparency?

[James]: I believe there’s a cultural problem at CBP.

[Silvia]: He said that there is a cultural problem, mainly on the part of border patrol, which, remember, is part of CBP. Tomsheck says that they promote a false notion that they’re the primary security agency in the country.

[James]: And assert a completely false notion that they are the highest integrity law enforcement organization in the country.

[Silvia]: And the one with the highest integrity. Tomsheck described the cultural problem in two words:

[James]: Institutional narcissism.

[Silvia]: Institutional narcissism. Not wanting to see that there are big problems with corruption and misconduct. And, perhaps most importantly, not wanting the public —via the media— to see it. That’s the reason for the lack of transparency.

I also spoke with some border patrol agents who are already retired. And they told me that, in their experience, cases of misconduct are rare, and it’s just a few “bad apples,” isolates cases.

[James]: I think it’s certainly a case that exceeds the phrase “a few bad apples.”

[Silvia]: Which Tomsheck does not agree with. And there’s data that shows there are serious problems inside the agency. For example, according to a study by the Cato Institute —a center for Libertarian studies— between 2006 and 2016, the border patrol had the highest rate of dismissal for discipline or performance problems of any government security agency.

And this is important because…

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: Donald Trump’s administration established new guidelines to reinforce the control of immigration into the United States with an aggressive plan that includes accelerating the immigrant deportation process and hiring 15.000 new agents.

[Silvia]: Trump wants to hire more agents: 10.000 for ICE, Immigration and Customs Enforcement —the agents that detain undocumented immigrants in the United States— and 5.000 for CBP. But it wouldn’t the first time CBP has grown so much.

After the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, in his administration, George W. Bush hired around 10.000 new agents. And that level of growth presented quite a few problems.

[Guillermo Cantor]: With such excessive and accelerated growth, what occurred is that the occurrence of situations of abuse of authority, of the use of excessive force, of… of inappropriate and improper conducts have been very common.

[Silvia]: This is Guillermo Cantor, the research director at the American Immigration Council, a non-profit organization that works on issues related to immigration politics.

[Guillermo]: To a large extent, the agency has operated outside of… outside of control, without the controls that are imposed on any other… other agency of this size.

[Silvia]: And there are several cases.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist 1]: A Hispanic border patrol officer is accused of sexually abusing a minor. Child pornography was also found in his possession. Alejandro Domínguez is detained in a prison…

[Journalist 2]: Undocumented immigrants in the United States run the risk of suffering sexual abuse at detention centers, according to a report from Human Rights Watch.

[Journalist 3]: The government of Honduras has asked the United States to investigate the case of three Honduran immigrants that were kidnapped and raped by a border patrol agent in Mision, south Texas.

[Silvia]: And they aren’t isolated. For example, last year —in 2018— the ACLU started publishing documents they received from the Department of Homeland Security.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: It consists of 30.000 pages of documents, recordings, and videos that provide evidence for and report acts of abuse committed by agents of the patrol for years, eh?

[Silvia]: This was after a years-long legal battle to get the CBP and the Department of Homeland Security to share more information about the mistreatment of minors in CBP custody, like J. The ACLU and other organizations had already documented 116 cases of mistreatment of minors between March and May of 2014 —a year in which the number of unaccompanied minors arriving in the United States rose suddenly.

Well, according to the ACLU, in these 30.000 pages of documents —in the recordings, and videos covering accusation from 2009 to 2014— there is evidence of mistreatment of minors, including sexual abuse and harassment. Cases very similar to J’s.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: A perfect example is the testimony of this 14-year-old girl who was arrested by the border patrol.

[MINOR]: He searched me and told me I had to pull down my pants.

[Silvia]: OK. I don’t want to disorient or bore you with the data, but it’s important to highlight a few more reports because they show what happens inside the agency once a complaint is made.

An organization called Freedom for Immigrants found that between May of 2014 and July of 2016, the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security received more than 1.000 reports of sexual abuse from detained individuals. That is more than one complaint a day. And only 24 of those complaints were investigated.

Guillermo and his team at the American Immigration Council analyzed similar data from previous years and found that…

[Guillermo]: To a large extent, these complaints aren’t investigated with the amount of rigor one would like.

[Silvia]: Clarita and J’s complaint appears in the data Freedom for Immigrants shared with me. It’s recorded in July of 2016 as “coerced sexual conduct.” That’s one of the categories the department uses. There’s also a more general category which is, “physical or sexual abuse,” another which is “sexual harassment.”

In the end, the internal investigation into Clarita’s and J’s complaint was open for seven months, and the data doesn’t say why it was closed. I asked the agency for the report of the investigation, but almost a year later, they haven’t answered me. I contacted an investigator from CBP who worked on the case, but he told me he couldn’t talk about the investigation because there was an open legal case. Angélica, the sisters’ lawyer, also asked for the report on the investigation and CBP responded with a document about the sisters’ arrest. That was it.

But, in October of 2018, the Associated Press reported that they did receive a redacted report about the investigation, and according to that, the agency investigators determined that they could not verify the sisters’ complaint due to a lack of physical evidence. In addition, the station didn’t have security cameras in the area where they take the detained person’s information; they didn’t analyze the fingerprints in the room because the sisters said they hadn’t touched anything; and Agent F said he was left alone with the sisters because there weren’t enough officers.

According to the investigation report, Agent F spoke with investigators three times. The last time, one investigator noted that the agent was nervous and that he was constantly looking over a statement that he had already prepared in the first interview. The Associated Press says that the investigators took the case to a prosecutor, and he agreed with them: it lacked evidence.

CBP has not stated if Agent F was disciplined in any way.

According to the analysis of Guillermo and his team, a high percentage of cases that are investigated and have been closed result in “no action taken” against the accused agent.

[Guillermo]: In other words, no disciplinary or corrective action takes place.

[Silvia]: And Guillermo says that this is worrying, especially if we remember how big this agency is…

[Guillermo]: When there are no internal controls, when there are no incentive structures and sanctions, the personnel really don’t have.. they don’t have many controls regarding rules of conduct, so they’re more prone to act with impunity.

[Silvia]: When they respond to reports from organizations like Guillermo’s or journalistic investigations, CBP insists that they are doing their part.

In response to the report from the 2018 ACLU regarding the abuse of minors, for example, CBP says that in the last three years they have created internal policies to avoid abuse, including new standards on how to transport, escort, detain, and seize immigrants. The release also mentioned measures the CBP has taken to prevent and respond to sexual abuse and assault.

The agency has a zero tolerance policy for this kind of abuse, and I’ve been trying to confirm more details about this policy. For example, it says that the agency hired a person to —among other things— conduct an annual review of investigations into sexual assault. But who this person is isn’t published anywhere.

I requested an interview with him or her. The CBP press officer at the time responded with information that was already published on their website and asked what more I wanted to know. In the end, he told me that I had to wait for the answer to a freedom of information request on the topic. He never told me who this person was. And my request is still open.

In 2016, the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security published a report criticizing the CBP’s lack of progress in detecting, stopping and addressing sexual abuse. For example, it says that the agency hadn’t created plans and strategies to implement regulations on the topic, that they had concentrated on creating policies rather than taking concrete actions, like training their employees. According to the report, CBP is taking measures to address the Office of the Inspector General’s recommendations.

But it’s not clear what they’ve done since that report. Again, they refused to speak with me. And since the zero tolerance policy on abuse was implemented, CBP has only published one annual report —also in 2016— that talks about general measures without getting into the details.

[Angélica]: Hello?

[Silvia]: Hello.

[Angélica]: Hi, excuse me…

[Silvia]: Hi, OK…

I called Angélica in early 2019 to get up to date with the suit in federal court. According to case documents, they had reached an agreement with the government.

[Angélica]: Typically these cases are… the settlement is in money, right? A sum of money so the client can continue with their life despite having been through a traumatic event.

[Silvia]: And with this settlement, the cases never had to go to court.

When we spoke last year, I remember you said that sometimes these cases don’t get resolved, like there’s… there’s a chance that it won’t be resolved. Having reached a settlement, do you feel like it’s resolved, or not really? Or, is that one way to resolve it? Let’s say.

[Angélica]: Well, resolving it… I think we reached a settlement that for us and our client is satisfactory. Now, what we obviously don’t… don’t know when we reach a settlement is what the government is going to do, for example, with… with that individual, right?

[Silvia]: With Agent F. Remember that the agency has not stated what happened to him. I asked them before finishing this episode, but they haven’t answered. I called the border patrol station in Presidio, and they wouldn’t confirm if he still worked there either.

Looking at it from CBP’s perspective —or someone who… who doesn’t want to believe these things are happening, right?— what I wonder is if reaching a settlement is a sign that, like: “It was nothing.”

[Angélica]: Well, when we reach a settlement, that means that the evidence was never presented in… in court, right? So the court never had that chance to say that…. uh, what happened didn’t happen. CBP obviously can say certain things, but what we have seen in the reports is that abuses occur. This isn’t the only case that’s occurred. It occurs in many, many kinds of cases.

[Silvia]: And what usually happens is that they reach a settlement, according to what Angélica told me.

An analysis by The Guardian revealed that between 2005 and 2017, the government paid more that 60 million dollars in legal settlements in cases against border patrol agents, mainly due to deaths, damages for reckless driving and civil right violations.

In this case, the government will pay 125.000 dollars to J. A number well below the 750.000 the ACLU had asked in the legal claim at the beginning of the case.

But Angélica sees the positive side of this result.

[Angélica]: For us, uh… it’s really a victory to have managed to get a favor… favorable outcome for our client, and with that outcome, we’re sending a message to the government that they can’t abuse our immigrants physically or sexually without consequences.

[Silvia]: I asked her about Clarita and J.

[Angélica]: Obviously, sometimes they still, unfortunately… remember that terrible event. But they are both doing… they are both doing… doing very well and obviously recovering with their loved ones.

[Silvia]: J is still in California, like her mom. She graduated from high school and is studying at a community college. Clarita got married. She’s back in Guatemala.

[Daniel]: Silvia Viñas is an editor for Radio Ambulante. She lives in London. Silvia reported and investigated this story with the support of the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas and me. Mixing and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Victoria Estrada, Miranda Mazariegos, Diana Morales, Patrick Moseley, Ana Prieto, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Every Friday we send out an email in which our team recommends movies, music, series, books, and podcasts that inspire us. It has great links for you to enjoy over the weekend. You can subscribe on our website at radioambulante.org/correo. Again that’s radioambulante.org/correo.

Watch out, if you use Gmail, check your spam folder and drag the email to your inbox so you don’t miss it.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón Thanks for listening.