Translation – Jumping the Wall

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

[Carlos Framb]: One day I opened the door and I heard her crying, alone in her bed.

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: This is Carlos Framb, a Colombian writer. And here he’s talking about his mother, Luzmila, with whom he was extraordinarily close. In 2007, Luzmila was suffering from various diseases. She was in constant pain and was going blind.

[Carlos]: Then I got closer. And she told me, crying: “I don’t want to live if I have to be blind like this. Negrito, I don’t want to, I just don’t.” So I told her: “Tell me, negra, I’ll do whatever you tell me.”

[Daniel]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Today we’re going back to our archives to share with you one of our favorite stories, published originally in 2015.

And we start with a question, a pretty complicated question:

Is there any case where it is OK to help someone die? And if yes, under what circumstances?

Our managing editor, Camila Segura, traveled to Medellín to talk with Carlos.

[Camila Segura]: Carlos was born in Sonsón, a small town about two and a half hours outside of Medellín. At that time, it was a very traditional and Catholic place.

The biggest tragedy of his youth, the one that left an impression on him, was the death of his maternal grandmother. Carlos was about 14 years old, and Carmelita–as she was known–had gotten skin cancer.

She was 85 years old and also lived in Sonsón. For months, she suffered horribly. She couldn’t wear anything, so they had to wrap her up in a plastic that ripped her skin off whenever they removed it.

[Carlos]: So, all that suffering and torment, and to witness how the skin of this old lady, so beloved, was peeling off… the skin, right. It was just raw flesh.

[Camila]: Carlos felt that it wasn’t fair that someone could suffer so much and had to wait for death just to get relief.

[Carlos]: And throughout the years, my mother and I remembered Carmelita’s agony. We both agreed that her suffering didn’t make any sense.

[Camila]: Despite growing up in a Catholic family, Carlos started to distance himself from religion due to this incident. He didn’t understand how Catholicism could be against euthanasia.

When he graduated from high school, Carlos moved to Medellín to live with his dad. Soon after he was followed by his mother and his brother. He dedicated himself to writing and published a couple of books of poetry. For twenty years, he lived happily in a big house with his parents and two aunts.

When he was 27 years old, he started working and stopped writing. Everything began to change in 2000 when his mother broke her leg. In a span of two years his father and two aunts died, and Luzmila’s health began to deteriorate.

[Carlos]: She was already in her seventies. They discovered she had arthritis and osteoporosis. Besides that, she was quickly losing her vision, three illnesses. My mother quickly went from being what I would call, well, not necessarily cheerful, but, well, an active and social woman, who was, well, moving, to a sad woman.

[Camila]: Carlos was left with his mother and a small dog. He had begun to teach reading classes in a school and went from living in this big house full of people to living with his mom in a small apartment. It wasn’t unpleasant, but it was still small —very different from the life he had before. As a result of this downsizing, something happened between Carlos and Luzmila.

[Carlos]: It was then when I discovered that my mother and I were more like friends. So, in the end, the relationship between her and I was very co-dependent and very affectionate. It was painful for me, right? To see her feeble and helpless.

[Camila]: His brother Iván had returned to Medellín after 20 years in the United States. But even though he lived close, Carlos was the one that really took care of Luzmila.

[Carlos]: I was a teacher, you know? Basically, my life was teaching in the school, taking care of her, and spending time with her. She was in pain and by herself a lot of the time. Things, well, started to get complicated. Every day she complained, it was… like a mantra, you know? “God, when are you going to remember me? Remember me… this is so horrible. I don’t want to live.”

[Camila]: He would leave for school early every day and from there, he would call her a couple of times. Normally, Luzmila would stay in bed until 9 or 9:30am. She listened to the radio and prayed the rosary. She would get up, take a bath, eat breakfast, and —depending on how she felt— either go back to bed or sit by the window to feel the sun, barely able to see anything. Carlos came home for lunch.

[Carlos]: So basically in the afternoons, either I stayed with her, I read to her a lot —she liked it when I read to her. Or we went out, to the doctor or to take the dog out for a walk.

[Camila]: But even those walks that she loved so much were becoming very difficult because of the pain she felt throughout her body. By January 2007, she could only see in splotches, without being able to distinguish details. And one of the things that hurt her the most was not being able to see Carlos’ face.

[Carlos]: For example, she loved to watch television at night and to read. She lost that pretty quickly. She now couldn’t do anything in the kitchen. She started to feel useless.

[Camila]: In April 2007, Luzmila turned 82 years old and Carlos wanted to take her out to a restaurant, but she didn’t want to go. So they ordered something and improvised a celebration, but Carlos felt bad about how simple the event was.

[Carlos]: I told her not to worry because for her next birthday I was going to have her serenaded, but she said to me: “Oh, no, mijito, God forbid. I know I’m not going to make it past this year. I don’t want to.”

[Camila]: Luzmila had been saying things like this for some time already, but Carlos’s ideas on the right to die with dignity had been relatively clear since he had seen how his grandmother had died. Later —as an adult— he read philosophers and others that helped reinforce his ideas. One book in particular made a huge impact. It’s called Final Exit.

[Carlos]: The book investigates the different ways to commit suicide, specifically the most effective, quick, and painless. And I had it there, with me.

So it recommends a mix of strong sleeping pills, barbiturates, and morphine, right? It was lethal.

[Camila]: He got the book in the 90s after a close friend tried to kill himself with pills, but failed. He read it before his mother was even sick. And that detail is important, because what’s clear is that, for a long time, Carlos had been thinking of dignified and sweet —as he says— ways of dying.

[Carlos]: For many years I even had, in a drawer in my desk, the dosage. It was there: the pills, the boxes, and the morphine. Until I threw them out thinking they had already expired.

[Camila]: For Carlos, having the lethal dosage in his desk was simply a question of being cautious. Like someone who has aspirin for a headache or a band-aid in case they cut themselves.

[Carlos]: Let’s say that it was there as a precaution. Reason tells us to be prepared, not to wait until you’re a quadriplegic to see what you would do, right? And I believe I should, in this moment —even if I am not thinking about killing myself today or tomorrow—, I should have those drugs within reach because anything could happen.

[Camila]: So around May 2007, Carlos —facing his mother’s daily suffering and explicit desire to die— started to bring up the subject in a much more direct manner.

[Carlos]: My mother insisted that, for her, it was God that gives life and takes it away.

[Camila]: But he made it very clear to her.

[Carlos]: That if I were in that kind of situation, I would kill himself in a gentle and peaceful way —of course. Pills, tablets, injection, whatever.

[Camila]: Carlos used to talk to her about this and other things: abortion, homosexuality, euthanasia. He told me that despite his mother being a very religious person, she had a lot of liberal views: often she would agree with Carlos’s beliefs. Which is no small thing, if you consider where she came from, her age, and her generation.

Carlos told me that he translated some parts of the book Final Exit for his mother and gave her a couple of films where someone receives the help of a loved one to die.

[Carlos]: She watched with me and leaned towards me because she couldn’t see, but I was telling her what was happening . And it’s interesting, my mother’s, ¿opinion on the ending?: “Perfect, and of course, very well done.”

[Camila]: But the book, the movies… this process that Carlos describes so innocently, some would call it “manipulation”. When I mentioned this interpretation to him, he responded to me like this:

[Carlos]: Well, I don’t think that’s the word. I could just as easily say that religion manipulates people, but no, you’re just born and they latch you on to this or that belief.

[Camila]: Carlos always respected Luzmila’s religious beliefs.

[Carlos]: Religion, for my mother, was a comfort, it was company. So it wasn’t about that, but rather to show her this notion of a compassionate, merciful God, you know?

[Camila]: In September of 2007, a few months after turning 82 years old, Luzmila’s ophthalmologist suggested that she undergo an operation to remove her cataracts. He didn’t guarantee that it would work, but it was her last hope to get back her vision. She didn’t want to, but Carlos convinced her.

The operation was a failure.

[Carlos]: I think that was the turning point because even though she had been in a lot of pain, what really hurt her the most was the blindness.

[Camila]: One day, shortly after the operation, Carlos asked the school for permission to leave early.

[Carlos]: She didn’t know. I opened the door and heard her crying, alone in her bed. Then I got closer and she said to me crying: “I don’t want to live if I have to be blind like this, Negrito. I don’t want to, I just don’t.” So I told her: “Tell me, negra, I’ll do whatever you tell me.”

[Camila]: A few days later, Luzmila told Carlos explicitly that she was ready now.

[Carlos]: So she told me: “Well, get what you need.” So I felt like that was it… I knew now that our days were numbered.

[Camila]: He said “our.” And that’s because Carlos hadn’t told his mother something.

[Carlos]: I had already decided too… without her knowledge, that if she accepted, I would also take the lethal… lethal cocktail.

Now, of course, my mother had no idea that I planned to join her. There was no way she would have allowed it. But I.. I wanted that ending, that final outcome, with her.

[Camila]: And that’s because during this period, Carlos was going through a really rough time. He was 42 years old and had spent six years working at a school at a job he did not enjoy. He had stopped writing in his 20s and felt lost, unmotivated.

[Carlos]: Work, my mother being so sick. I didn’t have a partner, to say the least, or children, or connections, or ties. And also the idea of her absence, who had become my reason for living… So it was like this bubble was going to burst, right? And I wasn’t willing to take on that loneliness.

[Camila]: Carlos began to leave everything in order. He quit the school under the pretext of having to take care of his mother. And one Saturday…

[Carlos]: October 20th, she told me: “Mijito, don’t forget to get the stuff.” That was like a euphemism for… I already knew that this was going to be the day.

[Camila]: Carlos’s brother Ivan came to visit that Saturday. He saw Carlos writing at his desk and his mother in the kitchen. This is Ivan.

[Iván]: She looked very depressed, you know?I did notice… like always, you know? But that day, I saw how sad she was and so I stayed there for approximately 15 minutes, I think. Then I told her that tomorrow… tomorrow I would come back, right? Afterwards, I gave her a hug and said goodbye.

[Camila]: When Ivan left, Carlos told his mother that he already had the drugs.

[Carlos]: It was her decision and she told me, “What else can I wait for?” Anyhow… There came a moment where she went to pray. I saw her kneeling at the foot of the bed and… and I knew that that was it, she was ready.

She came back from praying. She brought a box of the sleeping pills that she used to take in order to adjust. We hugged and that was the only moment, let’s say, of crying or drama, you know?. I contained myself so that there.. there wasn’t this dramatic touch to go along with something that, to me, seemed like this really beautiful transition.

[Camila]: It was something like nine o’clock at night. They drank some coffee with toast and left the kitchen.

[Carlos]: I prepared the cocktail in the blender with peach yogurt in a mug that I still have. She came with me. We went to the bed. I placed the mug on the nightstand and she smoked a cigarette. She gave me suggestions about my brother, that I should spend time with him… the kind of clothes she wanted to be buried in… that she wanted a lot of people at the funeral. She was at peace. She finished the cigarette and drank the… the liquid, the mixture, right?

And what happened next was this lapse in which she was quickly falling asleep, let’s say. In 10 minutes she was in a deep sleep. Obviously, the drugs and the morphine were, well, really potent. So what came next was five to seven minutes of really… really heavy breathing, like… like snoring almost, and in one moment, it stopped. That was it.

I knew that… that she had jumped the wall. And I was going to follow.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after the break.

[Ad]: This message comes from NPR sponsor, Squarespace. Squarespace is the all-in-one platform to build an online presence and run your business. Create your company’s website using customizable layouts, along with features including e-commerce functionality and mobile editing. And Squarespace offers built-in search engine optimization. Go to Squarespace.com/NPR for a free trial, and when you’re ready to launch, use the offer code NPR to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain.

[Latino USA]: Hi, I’m Maria Hinojosa host of the NPR show Latino USA. What do you think? There’s almost 60 million latinos and latinas in the US. We document those stories and those experiences each week. Find us on the NPR One app or wherever you get your podcast.

[How I Built This]: What does it take to build something from nothing? And what’s the process to build it? Each week on How I Built This, a behind the scenes with the founders of the most inspiring companies in the world.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. We left the story just as Carlos’ mom had taken the lethal cocktail. A few minutes later she was sound asleep, and gradually she stopped breathing. What she never knew was that Carlos was planning on doing the same.

Camila continues the story.

[Camila]: Carlos stayed in bed, lying next to her for about an hour.

[Carlos]: I was whispering into her ear while she started to get cold, right? It’s a really fast process when the body goes cold.

[Camila]: It was 1:30 in the morning more or less. He sat down to write a letter to his brother Ivan where he explained everything to him.

After he finished the letter, he went for a walk.

[Carlos]: I went around the neighborhood, the stadium, to say goodbye, you know? Then I went back, listened to music, some songs.

[Camila]: He prepared the cocktail, but before drinking it…

[Carlos]: I stopped in front of the mirror for a moment to look and to think that I could still go back, you know? I could change my mind. But no, I had already made the decision so I went and drank from the mug.

[Camila]: And he placed a plastic bag over his head. He had read that it was the surest way to die. You go to sleep and then you asphyxiate. He understood that he had two minutes of being awake before pulling the plastic bag over his head.

[Carlos]: So I put on the bag on the top of my head and went directly to bed and hugged my mother, thinking I would hug her and then go back to a face up position and pull the bag over. But no, I hugged her and that was it. I collapsed.

[Camila]: He didn’t get a chance to pull the bag over his head. The next day, Sunday, around noon, Ivan started to get this strong feeling of wanting to go to his mother’s house. Here’s Ivan.

[Iván]: So I got to the house and opened the door. I noticed there were some envelopes on the table, the envelopes said “for Ivan”, so… but, well, I didn’t touch them.

[Iván]: Then I went into the bathroom. When I looked at the bed, I saw my mother sleeping and my brother sleeping beside her. After that I said: “Oh, I’ll let them sleep.” Then, I came back and looked at him again because it seemed to me like there was something on his face. Something was off. I looked more closely and it looked like he had a bag or a plastic on his face and that’s when I had this shock and got a little worried.

So I got closer to my mother and touched her, I called her… and nothing, she didn’t respond. So I touched her and noticed that she was really cold. And when I saw that she wasn’t responding and that she was so cold, I realized immediately that she was dead. Well, I… I reacted, I was like: “Mom, mom, mom.” Then I called out to my brother and he was also… he looked to be unconscious.

[Camila]: Ivan saw sweat on Carlos’s face and suspected that he was alive. He tried to call for an ambulance but Carlos had disconnected the phone. He went downstairs to a neighbor and when he returned to the room, he saw that Carlos had pulled down the bag.

[Iván]: And I pulled it back up again, right? I took it off. But when he did that, that’s when he went into a coma.

[Camila]: The paramedics took him unconscious to the hospital. Ivan didn’t understand what had happened. First, he thought that his mother had died from natural causes.

[Iván]: Because of her health problems, anyway… and she probably suffered a heart attack that night. Maybe after seeing this my brother panicked, simply couldn’t go on, and committed suicide.

[Camila]: But later on, when the paramedics had already left, he sat down to read the letter that Carlos had left him. It started like this:

[Iván]: “Dear Ivan,

You have to be strong. There’s nothing tragic or dramatic here. So there shouldn’t be tears, shouts, or laments. This mercy killing was an act of love. Don’t blame yourself or anyone else. It was a liberating, rational, and carefully chosen death.”

[Carlos]: After three days I woke up in the hospital… it was everything you could imagine. Well, my mother was already buried and everything. And there were charges, homicide charges.

[Camila]: The day he woke up was, by chance, his birthday. He was in the psychiatric ward surrounded by lawyers and prosecutors. Shortly after, Ivan arrived.

They didn’t exactly talk about what had happened even though Ivan was dying for Carlos to tell him how everything had happened, why he didn’t tell him. The legal discussion was beginning and to Ivan, it seemed better not to ask a lot of questions.

[Iván]: Because I thought: “He’s already in this terrible situation… awaiting a long prison sentence and I’m going to bring all this up here. Maybe there has to be another opportunity to do that, you know?”

[Carlos]: And that night they took me to jail.

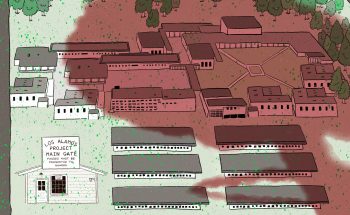

[Camila]: Carlos celebrated his 43rd birthday on the floor of a jail cell in the prosecutor’s office, a basement, where there were 15 to 20 more men. Those ten days were horrible.

[Carlos]: Nevertheless, I was happy to know that my mother was dead and that she was finally at peace. “Right, right”, I said: “It’s done. And if it gets too difficult without her, I could just try again.” I wasn’t ready to go to prison for twenty years, there was no way.

[Camila]: Carlos’s friends managed to get him transferred to a minimum security prison. While he was there, he started to get a lot of sympathy letters. The first to support him was his brother Ivan.

[Carlos]: He sent me news the first day, when I was in that bunker, telling me that he wouldn’t leave me alone, that I could count on him.

[Camila]: The legal process for Carlos lasted almost nine months. When they officially filed charges against him —in October 2007—, he was in the hospital’s psychiatric ward. A public defender recommended that he plead guilty, but Carlos didn’t want to.

After spending almost two months in jail, he went out for the first time to go to trial and to hear the case against him. The sentence would be between 33 and 50 years in jail. The prosecutor claimed that Carlos had taken advantage of Luzmila’s vulnerable state and had given her an overdose of morphine as she slept. What wasn’t clarified was how Carlos got Luzmila to drink the substance if she was asleep. The only evidence that the prosecution had was the letter Carlos had written to Ivan.

[Santiago Sierra]: The prosecution had given this arbitrary interpretation, right? They claimed that you could deduce from some specific words he had used that he had killed her and afterwards, committed suicide.

[Camila]: This is Santiago Sierra, one of Carlos’s lawyers. The defense asked for the letter to be excluded from evidence since it was obtained without a court order. The judge accepted the exclusion. So the prosecution could only count on the testimony of expert witnesses, but none of them was able to prove it had been a homicide. Ivan’s testimony was key.

[Santiago]: He established that his mother didn’t want to go on living and that she complained incessantly that God had forgotten about her.

[Camila]: Here’s Ivan:

[Iván]: What happened with my mother was not a homicide, okay? If you love another person that much like he loved her and what not… obviously, he wouldn’t do that to my mother. He simply always wanted the best for her, right?

[Camila]: During the trial, other people testified as well, and everyone reiterated that Luzmila constantly said that she wanted to die.

[Santiago]: There was a lot of corroborating evidence that she did in fact want to die despite being a Catholic woman, right? And that Carlos Framb started to do a pedagogical work with an eye toward demonstrating to her that it wasn’t immoral to commit suicide in those circumstances, right?

[Camila]: According to Carlos, the prosecution’s argument was religious.

[Carlos]: They were like: “This woman wouldn’t have been able to take her own life because it would have been a sin.” That was their stance all the way until the end.

[Camila]: The prosecution’s closing argument concentrated on the lack of proof showing Luzmila’s will to die —there weren’t any notes or recordings where she demonstrated her wish to commit suicide. And they declared that the defense’s hypothesis, that it was an assisted suicide, was an alibi to cover up the homicide. The defense, in turn, stressed that Carlos only facilitated his mother’s death by helping her to die.

But if you’re not a doctor, helping another person to commit suicide is illegal in Colombia. Nevertheless, in this case…

[Santiago]: The problem is that the legislation in Colombia stipulates that the induction of suicide is a prosecutable crime. What does that mean? The state can’t unofficially investigate it unless there’s a complaint.

[Carlos]: And since there wasn’t, the case fell apart. Because my brother always claimed, or rather, never claimed that he was victim despite pressure from the prosecution. And that was it, the case was dropped.

[Camila]: On March 27th, 2008, Carlos was freed. With time, Carlos learned to live without his mother. He’s doing OK, at peace, and writing again. He started with a book about this experience.

His relationship with his brother is going well even though everything was really tough for Ivan.

[Iván]: It was actually really traumatic for me, you know? The following months were depressing, filled with nerves, and everything else. It was terrible. After dealing with my mother’s death, I had to continue with my brother’s situation, it was both things at the same time. It was a nightmare.

[Camila]: Sometimes he felt angry thinking that Carlos should have told him his plan. But while Carlos was in jail, Ivan began to think about what he would have done.

[Iván]: In reality, if my mother had asked me, I wouldn’t have been able to go through with it, you know? Because I don’t know what you need… if it’s courage or what…but anyway. I did feel that at the very least I said:”My mother isn’t suffering like she was before.”

[Camila]: I asked Carlos if he thought that his brother and his friends were worried about him because he might try to commit suicide again. This was his answer:

[Carlos]: No, no, no.

[Camila]: According to Carlos, his friends know that he’s always enjoyed life.

[Carlos]: What happens is that I don’t see why there has to be some pain at the end just to account for this joy. I would be more than ready to go in the way I have always wanted to leave this life: with a good aftertaste. Because that cocktail can taste pretty sweet. If you add sugar… And If you don’t have any worries left, you can add lots of sugar.

[Daniel]: Camila Segura is the managing editor of Radio Ambulante and she lives in Bogotá.

Carlos Framb told this story about his mom in a book titled “At the Other Side of the Garden”, published in 2009. His most recent book, the novel “At the Shore of Oblivion” was published in 2018.

Thank you to Ana Cristina Restrepo, Angie Lopera, and Camilo Martinez.

This story was edited by Martina Castro, Silvia Viñas, Luis Trelles and me. Mixing and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Victoria Estrada, Andrea López Cruzado, Miranda Mazariegos, Diana Morales, Patrick Mosley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Luis Fernando Vargas, and Joseph Zárate. Carolina Guerrero is our CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

We have a mailing list on WhatsApp and we would like you to be a part of it. Every week we send out a link to the episode so you won’t miss it and can share it easily with your contact list. It’s a direct channel between you and us, but it’s not a group. We won’t send you spam or anything like that, but sometimes a few emoticons to appear.

If you want to join the list send a message to the number +57 322 9502192, and Jorge, our engagement editor, will add you. Again, the number is +57 322 9502192.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.