Translation – The Soldier and the Lieutenant

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Why should you listen to Radio Ambulante?

For the stories we bring you every week. For the voices we present, voices that you won’t hear anywhere else. We love to bring you these stories. Latin America is a complicated and wonderful region. We tell these stories to help you understand it better.

So, many of you have asked us how you can support Radio Ambulante. There are many ways. You can recommend us to a friend or leave a review on iTunes. If you go to a our website —radioambulante.org—, you can make a donation Producing this type of content is very expensive: from paying editors and producers, to renting studios and buying equipment. The help we receive, as small as it may be, means a lot.

And for our listeners in the US, please: consider donating to your local Public Radio station. You can donate by going to: donate.npr.org/RadioAmbulante. Donate is spelled: donate: D-O-N-A-T-E. Again that’s donate.npr.org/Radio Ambulante.

Thank you so much. And from all of us at Radio Ambulante, happy holidays.

Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. And today we’re visiting our archives to hear a story from Argentina. The story of a soldier, a lieutenant and an improbable friendship.

Let’s start with our reporter:

[Gisela Ederle, reporter]: I’m Gisela Ederle. A journalist from Buenos Aires.

[Daniel]: Ok, Gisela, are you ready?

[Gisela]: Yes.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Statement from the Military Junta]: The Military Junta, as the supreme authority of the state, announces to the people of Argentina that the Republic has recovered the Malvinas, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands in the name of our national heritage .

[Daniel]: Now, where does this audio come from?

[Gisela]: This audio was recorded on April 2nd, 1982, when the Argentine Military Junta announces what they called “the recovery” of the Malvinas Islands [known in the US and the UK as the Falkland Islands].

And for those who don’t know, the Malvinas are a set of more than 200 remote islands and islets that are very far south of our country. The nearest Argentine city is in Patagonia and is about 700 kilometers away. And it is important to know that these islands have been occupied by the British since 1833.

[Daniel]: And who lives there?

[Gisela]: British citizens.

[Daniel]: So they’re a bunch of remote islands, full of British people. Tell me why does that strike such a… I don’t know… deep cord with the Argentine people?

[Gisela]: It’s because we are brought up believing that the Malvinas belong to Argentina from a very early age. We even sing the March of the Malvinas every April 2nd.

(“THE MARCH OF THE MALVINAS” SOUNDBITE)

[Chorus]: The Argentine/ Malvinas/ The wind calls, the sea breaks…

[Gisela]: We have always felt that they were usurped by a colonizing force —by English pirates.

That’s why when the Argentine people heard the news about the recovery of the islands, it was something wonderful and surprising —even for members of the armed forces.

[Jorge Luis Reyes]: That day, when I get up in the morning, I see such a fuss in the officer’s cafeteria, people eating breakfast, and it was because they had recovered the Malvinas.

[Gisela]: This is Jorge Luis Reyes, and in 1982 he was a lieutenant in the Argentine Air Force. He was living on the military base at Mar del Plata, and that day he was in what they call the casino, meaning, the cafeteria. He was 25 and had a girlfriend he was thinking of marrying. He also had a promising career in the armed forces.

And he’s describing the moment he heard the announcement we heard at the beginning…

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Statement from the Military Junta]: The Republic has recovered the Falkland Islands…

[Gisela]: Which declared the recovery of the islands like it was fact. At that time they thought that sending soldiers and flying an Argentine flag would settle the issue.

So three days later, Reyes and hundreds of soldiers like him…

[Jorge Luis]: We took a five hour direct flight from Mar del Plata to the Malvinas airport.

[Gisela]: And when they landed…

[Jorge Luis]: We couldn’t believe it.

[Gisela]: That, Daniel, is the kind of national sentiment toward the Malvinas I was telling you about.

[Jorge Luis]: Being in the Malvinas was a dream for us; it awoke in us a feeling of patriotism, pride and personal satisfaction.

[Gisela]: And remember no one thought this was going to be a real war.

[Jorge Luis]: We really had no idea that… that we could see combat.

[Gisela]: It was all very confusing.

[Jorge Luis]: Because up to that moment people talked about how we would have a presence there.

[Gisela]: And that a week later…

[Jorge Luis]: The conflict would be settled diplomatically. That it would not escalate to something else.

[Gisela]: But the Junta’s rhetoric was different.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri]: These people that I am trying to represent as president of the Nation…

[Gisela]: This is Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri, the de facto president of Argentina, a dictator. And at that time he was giving a speech at the Plaza de Mayo, in downtown Buenos Aires, in front of thousands of people.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri]: But I am also prepared to punish anyone who dares to touch a square meter of Argentine soil.

[Gisela]: And, Daniel, you have to understand the context of all this. A six-year dictatorship was floundering. And they hoped that this war could keep them going. But at the same time, the Argentine people felt that reclaiming sovereignty over the islands was justified. So the people supported the recovery.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Speaker of the House]: Prime Minister!

[Gisela]: And all the while, the people of Great Britain wanted to reaffirm their sovereignty over the islands.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Margaret Thatcher]: Mr. Speaker, sir…

[Gisela]: This is Margaret Thatcher. The prime minister of Great Britain.

[Daniel]: Of course, a tough one, Thatcher. The Iron Lady.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Margaret Thatcher]: Condemning totally this unprovoked aggression by the government of Argentina against British territory.

[Gisela]: Margaret Thatcher is saying the Falklands are a British territory and that what Argentina did was an unjustified attack.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Margaret Thatcher]: It is the government’s objective to see that the Islands are free from occupation….

[Gisela]: They were going to remove the Argentine military from the islands.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Margaret Thatcher]: At the earliest possible moment.

[Gisela]: Immediately.

And Galtieri responded.

(DOCUMENTARY ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri]: If they want to come, let them come! We’ll show them a battle.

[Daniel]: Wow. So, they went to war?

[Gisela]: Yes. Galtieri provoked the British military. He told Thatcher and her army to come.

And well, they came.

And it was up to Reyes’ group to defend the airport.

[Jorge Luis]: The conflict with the British military started on May 1st with a bomber plane incoming from Ascension Island.

[Gisela]: So that day…

[Jorge Luis]: When the British attacked for the first time, my knees were shaking. I can’t deny I was afraid.

[Daniel]: No, well, Reyes was so young. What, 25, right? Had he been to war before.

[Gisela]: No, he had never been in a war. He had been in a field exercise during his training as an Air Force lieutenant, be he had never been in a real battle.

From the first day on, the bombing was constant. The British forces figured out right away that if they won the airport, they won the war. So they sent plane after plane.

[Jorge Luis]: Their single and crucial mission was destroying the runway.

[Gisela]: And they gave it all they had. Honestly, they assailed them with gunfire.

[Jorge Luis]: Missions, mission after mission, trying to neutralize the airport.

[Daniel]: And what was Reyes doing during all this? What was his role?

[Gisela]: Reyes’ job was to shoot down British planes. And he used an anti-aircraft battery, which is a cannon he shot at the British planes.

[Jorge Luis]: And our cannons weighed six and a half tons.

[Daniel]: So we aren’t talking about a small cannon.

[Gisela]: Not at all. They were very, very heavy. Imagine how it must have been when the head of the squadron decided to change their position, 15 days after the airstrikes began.

It was almost impossible because the cannons were so heavy. But also because….

[Jorge Luis]: The terrain there was very very muddy and soft. So, if you strayed off the set paths…

[Gisela]: The battery…

[Jorge Luis]: Would get stuck.

[Gisela]: It would get caught in the mud.

[Jorge Luis]: And we would have to get in the mud and try to get the cannons out.

[Daniel]: All that to move the cannons?

[Gisela]: Of course, because…

[Jorge Luis]: If you took too long…

[Gisela]: You sunk deeper and deeper.

[Jorge Luis]: It was really heavy and standing in the rain and all that, getting the cannons out was a mess.

[Daniel]: And really cold, right?

[Gisela]: The truth is I’ve never been to the Malvinas, but yes. Reyes told me he had it really bad.

[Jorge Luis]: The wind is intense. For example, we would set up the tents and they would fly away.

[Gisela]: And there were all kinds of precipitation.

[Jorge Luis]: There was snow coming down in flakes, mist, fog, heavy rain, light rain, heavy snow, light snow.

[Gisela]: Reyes and his whole battery had to change position under these conditions. So they moved the cannon, the artillery, the munitions, the tents, and the food. They moved everything. And moving just a kilometer took them three days.

[Daniel]: Wow.

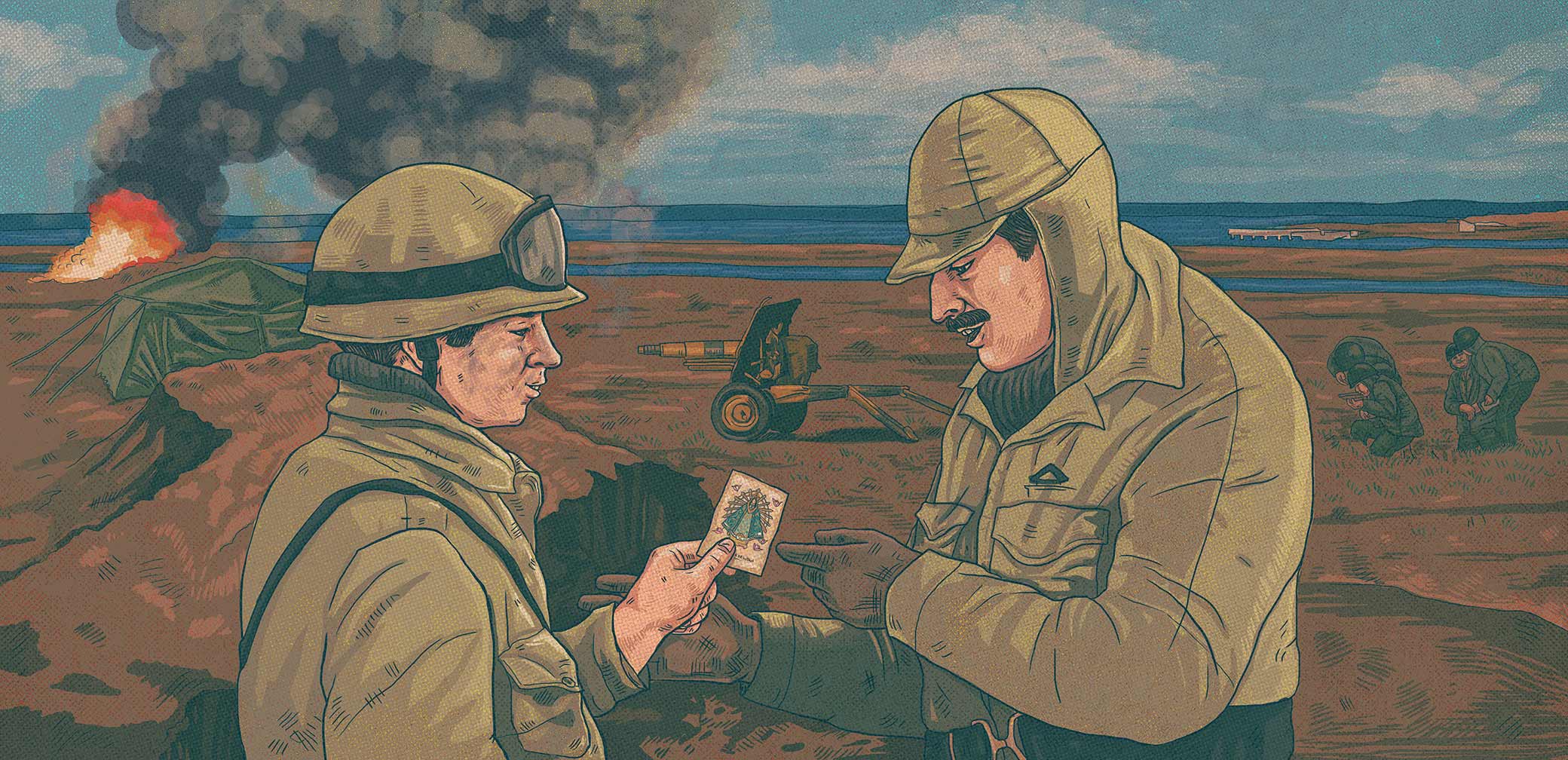

[Gisela]: They finally get to a place where there is a really shoddy trench, about fifteen feet away. It was a hole in the ground. They are a group of several men with a cannon in the middle of nowhere. During a British air strike. It looked like the end of the world.

And well, inside the trench…

[Jorge Luis]: It looked all wet, but half of it was burnt, like someone had lit a fire inside. Until at some point we see a foot starting to step out of there, then a leg, then a body. A soldier came out. There was a soldier: Rena

[Gisela]: Víctor Daniel Rena.

[Daniel]: What! Where? You mean, a guy comes out of this hole?

[Gisela]: Yes, exactly. Not just one but two soldiers came out. It was Rena and another soldier, Juan Palacios. They were both in the 25th Regiment. The 25th Bravos. Both were barely 18. Both were finishing up their mandatory military service and their mission in that trench was to defend the airport against an attack by land.

[Daniel]: Two young soldiers were going to defend the airport against the British?

[Gisela]: Exactly. That was part of what happened in Malvinas: improvisation. A military government bringing a lot of soldiers to a war that they weren’t even prepared for.

[Jorge Luis]: So on the side of the trench we were setting up…

[Gisela]: All of the artillery equipment.

[Jorge Luis]: Cannons, radars…

[Gisela]: And Rena and Palacios were really surprised to have all of those important armaments there.

[Jorge Luis]: So they came over to talk to us. He and the other guy, Juan Palacios, came out.

[Gisela]: Both soldiers are from a city called Río Cuarto in the province of Córdoba. Reyes and the men under his command were using a mechanical shovel to dig out a trench for the artillery. But when Reyes sees that shoddy trench Rena and Palacios were staying in, he feels bad for them and gives the order to build them a new trench as well.

[Jorge Luis]: So now they had a proper shelter. They were next to us.

[Gisela]: And you have to understand, Daniel, this is not a normal gesture.

[Daniel]: In what way?

[Gisela]: There weren’t… there aren’t strong ties between lieutenants and privates. That kind of gesture was very uncommon. And besides being very far apart in rank, they also were in different branches.

But none of that mattered to Reyes. And Reyes’ gesture –something so simple, right?– would become very important for Rena, and it marked the beginning of a friendship.

[Jorge Luis]: In the evening or in a calm moment, I liked to get close to the soldiers.

[Gisela]: And they talked for hours.

[Jorge Luis]: I did it with the people in my battery and I did it with them too. We talked about their families, what they did, what they hoped for, what they were studying, and what they wanted to do after they got out.

[Gisela]: And, well, that’s how he started to get to know Rena and become friends with him.

[Jorge Luis]: They extended an invitation. They said: “Come to Río Cuarto and I’ll tell my sister to cook; she is a really good cook.”

[Gisela]: And they liked to talk about what they did in their town in Córdoba.

[Jorge Luis]: “OK, yeah, we’re going to go to Río Cuarto.”

[Gisela]: They’re already thinking about what they’re going to do after the war.

[Daniel]: If they survive.

[Gisela]: Exactly. That’s just how Reyes felt.

[Jorge Luis]: Really, there probably isn’t any other place where they… where we were more similar, right? And where we grew closer to one another than right there, you know?

[Gisela]: When Reyes says “closer” what he is really saying is that they weren’t just under the same conditions, but also they were facing war together and…

[Jorge Luis]: Judging by how the battle was progressing, I knew or I thought I wasn’t going to make it out alive.

[Gisela]: In the two months they spent together they became real friends. The difference in rank between them disappeared. Reyes shared his food with Rena because the army’s food was famous for how bad it was.

[Jorge Luis]: A watered-down stew that was somewhat nutritious at best.

[Gisela]: While the officers, like Reyes, got a meal that was a little more respectable.

[Jorge Luis]: Ravioli with chicken, rice and stew. And there were different dishes. So we didn’t always eat the same thing.

[Daniel]: And of course, that kind of generosity isn’t normal in this context.

[Gisela]: No, it’s not normal at all. Reyes did things like offer them dry clothes. Imagine what it would be like for two soldiers living in a damp trench, nearly freezing, to have dry clothes. They had gone two months without changing their clothes. That meant a lot. And then Reyes even taught him how to shoot.

[Daniel]: Hold on. What? He didn’t know how to shoot?

[Gisela]: Yes. Look. What happened is that a lot of soldiers, like Rena, had little military training. And well, when Reyes found out that they had to defend the airport by land, he tested Rena’s aim. He grabbed two 200 liter barrels of fuel and put them a certain distance away to test him.

[Jorge Luis]: I say: “Well, go ahead. Load the rifle”. He loads the rifle… perfect. “Good. Shoot!” He would shoot but he couldn’t even hit it by accident. And I thought to myself: “This one is going to provide cover on land, but… he doesn’t know how to shoot!”

[Daniel]: And did he get better? Did he learn?

[Gisela]: Yes. Reyes told me that after a month everyone considered him to be a great soldier and he had already learned how to shoot. By June 1982, two months after arriving, the British airstrikes on the Argentine position at the airport got more and more intense.

And during one of the British airstrikes, one of the missiles lands near Rena’s trench and everything catches fire. His helmet, his weapon –everything he had in the trench– catches fire.

[Daniel]: But Rena makes it out OK?

[Gisela]: Yes, yes, he makes it out. But this happens at the worst possible time because that’s when they order him to go defend the front lines of the battle by land; which means going from the airport to the coast because the British were already coming on land.

[Daniel]: And Rena doesn’t even have a rifle to fight with. It was burnt in the fire.

[Gisela]: Yes, and just then Reyes helps him again. He gave him a rifle and a helmet. Even though, well, Rena didn’t want to accept it.

[Jorge Luis]: And he says: “But it says Air Force all over it”. “What do you care if it says Air Force as long as it works the same!”

[Daniel]: Well, then at least he could go into battle, right?

[Gisela]: That’s what he did. But before saying goodbye to Reyes, Rena felt like he owed him something and he had a gift for him.

[Jorge Luis]: He says “Look, I’m giving you my holy card of the Virgin of Luján”.

[Daniel]: The Virgin of what?

[Gisela]: The Virgin of Luján, the patron saint of the Argentine people. And Reyes didn’t want to accept it.

[Jorge Luis]: I say: “Look, no, take it with you because you’ll need it more than me”. And he says: “No, I have two!”

[Gisela]: Reyes asked Rena to write his name and the name of his city, Río Cuarto, on the back of the card. Reyes kept the card in a notebook he had in his pocket and said:

[Jorge Luis]: “I promise that when all this is over I’m going to go to Córdoba and we’re going to eat an amazing asado [Argentine barbecue].”

[Gisela]: And Rena obviously said yes…

[Jorge Luis]: “Come, I’ll be waiting”. We hugged and he left.

[Gisela]: And Reyes continued his mission, which was operating the artillery and trying to do what he could: defending the airport and shooting down

British aircraft. And he shot and shot and shot. And that is what the final battle consisted of –shooting until one side ran out of munitions.

[Daniel]: And? And that’s how the war ends?

[Gisela]: Exactly. The British gave the order to cease fire and effectively ended the war. Because if the British continued shooting and advancing as they were, it would have been a massacre.

[Daniel]: In other words, the Argentine resistance collapsed.

[Gisela]: Yes, they ran out of munitions. And the British took nine thousand Argentine soldiers as prisoners in the airport. One of those prisoners was Reyes.

[Jorge Luis]: Honestly, the image of the airport with all of the prisoners was like something from Dante.

[Gisela]: People wandering around like zombies. Some were looking for food, others were looking for shelter. They destroyed their own weapons so the British couldn’t use them. And well, in that context Reyes starts looking for Rena and thinks he would find him near the position they held in the battery during the war.

[Jorge Luis]: And when I go to the position, I see Palacios who was sitting on a rock with his head in his hands and in bad shape, mentally.

[Daniel]: Palacios is the soldier who lived in the trench with Rena, right?

[Gisela]: Yes, yes, he is. And Reyes asks if he had seen him:

[Jorge Luis]: He says: “Don’t look for him anymore. A mortar shell split him in half. He’s dead.”

[Daniel]: And Reyes was… devastated.

[Gisela]: Yes. Reyes tells me that the first thing he did when he found out was take out the holy card that Rena had given him.

[Jorge Luis]: And I wrote: “Killed in combat: June 14th, 1982”.

[Gisela]: When the war was over Reyes rebuilt his life in Buenos Aires. He married his girlfriend María Elena, and had five children. But the war was always there. Every year…

[Jorge Luis]: I thought about him every June 14th.

[Gisela]: He thought about Rena a lot.

[Jorge Luis]: Because I had gotten to know him and because of what we had developed.

[Gisela]: That date marked the day the war ended, and Reyes attended mass in honor of the fallen.

[Jorge Luis]: For the 658 victims, especially Víctor.

[Gisela]: For Víctor Rena. Reyes never forgot the war.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after the break.

[Ad]: This message comes from NPR’s sponsor Squarespace. If you’re ready to start your new business, get your unique domain and create a beautiful website with help from Squarespace’s 24/7 award-winning customer support. Head to Squarespace.com SLASH RADIO for a free trial and when you’re ready to launch, use the offer code RADIO to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain. Think it. Dream it. Make it. With Squarespace

[How I Built This]: What does it take to start something from nothing? And what does it take to actually built it? Every week on How I Built This, a behind the scenes with founders of some of the most inspiring companies in the world.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Gisela and I spoke several times during one week —she was in Buenos Aires and I was here in New York— about the story of Jorge Luis and Víctor. But I felt that I needed to understand the context better. So I called a friend.

[Gabriel Pasquini]: I’m Gabriel Pasquini. I’m an Argentine journalist and writer.

[Daniel]: And I asked him what happened after the war. Gabriel remembers it well. He was 16 when Galtieri announced the supposed recovery of Malvinas. And Gabriel told me that the media…

[Gabriel]: Convinced us day by day that we were winning. In other words, we, the Argentine people, were winning the war up until the day they said that we had surrendered.

[Daniel]: Which only made that loss more humiliating.

[Gabriel]: Once the war was over, people didn’t want to think about it anymore, and they forgot the war and the people who fought in it.

[Daniel]: The shame of failing on the battlefield was added to the list of crimes attributed to the Military Junta. A Junta that did not last much longer, by the way.

[Gabriel]: And all of a sudden, when we lost, we declared ourselves victims, we had been deceived, and the only ones to blame were the military officials.

[Daniel]: A year and a half after the ceasefire, democracy had replaced the Military Junta. But long after the dictatorship, the people who fought in Malvinas fell into oblivion.

[Gabriel]: And it was a long time before the civilian government started to give them pensions, support them, help them and talk about the issue.

[Daniel]: Because they didn’t just forget about the soldiers, no. The Argentine people also forgot that a large majority of them had supported the war, that nationalist rhetoric had seduced the country.

[Gabriel]: And in turn, the image they constructed of the soldier in Malvinas was a young man who had been taken to war by force, and that he had really been victim to the Argentine military, their superiors, their improvisation, their cruelty, and their corruption, rather than the British.

[Gisela]: Yes, exactly. That is the image people have of the soldiers. And they are also seen as victims of state terrorism because we had spent six years under a dictatorship. And that was also the cause of the national shame and humiliation. In the case of Reyes, for example, he decided not to talk about Malvinas for a long time.

[Jorge Luis]: For the first 18 years after the war I practically didn’t talk about it at all, not even at home, not even with my children.

[Gisela]: It was only after 18 years that Reyes…

[Jorge Luis]: I not only talked with my family and friends, I even wrote a book.

[Daniel]: A book?

[Gisela]: Yes, he wrote a book that ended up being a diary of the war. He sat down to write and it was a kind of therapy. All the feelings he had kept for so long came out of him at once.

[Jorge Luis]: I realized that I had subconsciously recorded everything, that no detail had escaped from me and that I remembered a great deal of things. So it was like a… like a recovery exercise.

[Daniel]: Did you record him reading?

[Gisela]: Yes.

[Jorge Luis]: Let me see…

[Gisela]: When I recorded him reading, I saw someone who couldn’t stop remembering things. And the part that describes Rena’s death is one of the most important moments in the book.

[Jorge Luis]: This young man’s passing weighed on me very much. As did the passing of the others. Poor Víctor! Without a doubt it wasn’t an even fight, but he wasn’t afraid. He was there, faced with the defense of the country. I hope that our fellow patriots know to value the attitude of all these men who despite all limitations fought with valor that exceeded their own strength.

[Daniel]: What happened with this manuscript? I mean, is it published? Did it end up in bookstores? What does he do with that text?

[Gisela]: Reyes never managed to publish the manuscript. He wrote it and then left it at an Air Force office that is tasked with providing support to veterans of Malvinas.

[Jorge Luis]: I didn’t hear anything after that. I left it there and went on with my life. I never returned to that.

[Gisela]: And really, if it had been up to Reyes, that story would have stayed there, forgotten in that Air Force office. But something curious happened.

Someone in the office read that manuscript and apparently transcribed the part that dealt with Rena’s death.

And that story started to circulate on social media. Reyes himself didn’t even know that this had happened. Until in 2011 the story of the friendship between Reyes and Rena appeared on a web page called “Nunca olvidemos a nuestros héroes” [We shall never forget our heroes].

[Germán Stoessel]: We were trying to share, I don’t know, stories about police officers, firefighters, a lot about Malvinas, about our history.

[Gisela]: This is Germán Stoessel, one of the site’s administrators. And he doesn’t really remember how he found Reyes’ writing. He thinks that at some point someone shared it with him on Facebook and he decided to put it on the site.

But the important thing here has to do with the error Germán found in the story.

[Germán]: In that story it says that Víctor Daniel Rena is a member of the 25th infantry regiment.

[Gisela]: People who read a lot about Malvinas know that that regiment only had…

[Germán]: 12 fallen soldiers.

[Gisela]: But those 12 casualties occurred during the month of May.

[Daniel]: But Rena died in June.

[Gisela]: Exactly! June 14. That’s the error. It’s impossible that Rena died on the day Reyes said.

[Daniel]: So, Reyes got the date wrong?

[Gisela]: Germán still isn’t sure, but he started looking into it. So first he looks at a list of fallen soldiers that the Ministry of Defense keeps.

[Germán]: And no, he doesn’t appear on the list.

[Daniel]: Which means that Rena could still be alive?

[Gisela]: Well, first of all, it was clear at least that Rena hadn’t died in the war. But Germán still didn’t know if he died later. Remember that this is happening 29 years after the war.

[Daniel]: And what could he do to confirm if Rena was dead or alive?

[Gisela]: Germán did it the old fashioned way: he looked for the name Rena in the phonebook.

[Daniel]: And?

[Gisela]: And he found a Víctor Rena living in Córdoba. And he called him.

[Víctor]: Hello, my name is Víctor Daniel Rena.

[Gisela]: And yes, it was him.

[Germán]: Then, honestly, a chill ran up my spine. I got nervous because I didn’t have any more doubt about it. He was alive.

[Gisela]: Then Germán explains why he’s calling.

[Víctor]: Since they had thought I was dead, I didn’t even know I was dead…

[Gisela]: It’s great!

[Daniel]: That Córdoba accent is awesome, don’t you think? So, of course, the next step is putting these two long-lost friends in touch.

[Gisela]: Of course, definitely. But when he looked him up in the phonebook…

[Germán]: I found 500 thousand Reyes.

[Gisela]: But he kept looking. He googled Reyes’ Anti-aircraft Unit and found another list of veterans. And that’s how he got his number. He called him and gave him Rena’s number.

[Daniel]: And he called him right away, I imagine.

[Gisela]: Yes, but Reyes wasn’t alone. The first time he calls Rena his whole family is with him –his wife and his five children.

[Jorge Luis]: They were all by my side and that was how we got in touch.

[Víctor]: When he calls, he says “Víctor?” “Yes”, and he broke down, he broke down and well, then I did too, and well, it was very emotional. And well, I think we shed thousands and thousands of tears. And it was a huge surprise because through all that there’s this story that goes way back and well…

[Daniel]: But how is it that Rena survives in the end? Why does the other soldier… His name was Palacios, right? How is it that Palacios thought he was dead?

[Gisela]: That’s a great question, and it’s the main question they both had. Once they got over the excitement of having found each other again after 29 years, they started trying to piece together what happened on June 14, 1982.

[Víctor]: That night when I say goodbye we hug. It was a dark night. And it was almost morning by the time we headed to the Dos Hermanas hill…

[Gisela]: Rena says night had already fallen when he and Reyes said goodbye and that Rena had to go to the front lines.

[Jorge Luis]: While he’s advancing he got separated from the other soldiers with him at the airport because of all the action in combat.

[Gisela]: It was the final battle. It was total chaos. It was at night with bombs falling all over. You could barely see anything in the crossfire. Rena found four soldiers from Buenos Aires who he didn’t know – and the only one with a rifle was Rena.

[Daniel]: But why are four unarmed soldiers heading toward the frontlines?

[Gisela]: They were doing their duty.

[Daniel]: Without rifles? But what are they going to do there?

[Gisela]: I imagine they would do whatever they could.

[Daniel]: Die?

[Gisela]: Die. Exactly. In all the gunfire and bombings, there’s an explosion and the five of them are thrown through the air. So Rena is sprawled out on the ground, bleeding out in the dark. Everyone was advancing to the front, so other groups were pushing ahead a few meters away. Palacios, the other soldier from the trench, was among them. But they were moving ahead slowly, as best they could. And when Palacios sees that the four soldiers from Buenos Aires have fallen in battle…

[Víctor]: Really, when they saw me fall, they thought I had died.

[Daniel]: How did he survive?

[Gisela]: First of all, it was all thanks to Reyes. Reyes had loaned him that rifle and that helmet. And like I was telling you, a piece of shrapnel hit him in the forehead.

[Víctor]: And the helmet protected my head.

[Gisela]: Another piece of the bomb hit the rifle, which blocked it and in doing so it cut a whole side of his body.

[Víctor]: And in a way, the rifle that broke helped me a lot.

[Gisela]: So he is severely wounded. And on the next day, June 14th, after the cease fire was already in effect, the British troops rescued him.

[Daniel]: And why didn’t Reyes see Rena again. Weren’t they both prisoners?

[Gisela]: They end up sending Rena to a military field hospital and they send him back to the mainland after Reyes, so they never cross paths.

And well, after that first call, Rena and Reyes agreed to finally see each other in person on June 20th, 2011.

It would be in Río Cuarto, and the whole town of Río Cuarto, which is a small town, was abuzz. All of Rena’s neighbors knew he was going to have this reunion after 29 years. And for Reyes’ family…

[Jorge Luis]: The story was so powerful and important to us that all of my children put everything they had to do on hold so we could all get together and drive to Río Cuarto in my truck.

[Daniel]: So Rena was just as important to the rest of the family. By that time he had taken on a kind of mythic quality, not just for Reyes but for everyone.

[Gisela]: Yes, I believe that Rena was more like another member of the family. María Elena, Reyes’ wife, and their five children knew this story of friendship that had branded the lieutenant so deeply.

Throughout the eight hour journey from Buenos Aires to Río Cuarto, Reyes could only think about all that had happened to bring him to that moment: Rena’s death, the holy card with the date marking the end of the war written on the back –they were mixing in one swell of emotions in Reyes. In fact, he told me that 90 kilometers before getting there…

[Jorge Luis]: I stopped the car there and said to myself: “Just think, after so many years and so many kilometers, after all that happened and everything else, we’re in the final chapter, we’re 90 kilometers away from embracing again and picking up where we left off in such a long story.” So I waited before setting out again because I liked to think in that moment about everything that united us, in that final chapter, and everything that had kept us apart.

[Gisela]: The story was so touching that the media in Río Cuarto found out that Reyes was coming and were there at Rena’s door so they wouldn’t miss the reunion.

[Víctor]: And well, the press had already gathered. At some point they told him that I had arrived, and well, he reaches the front of the house…

[Gisela]: Reyes got out of his car and Rena went onto the sidewalk to greet him.

[Víctor]: And when we saw each other, face to face, he looked a little older but I never forgot his face.

[Jorge Luis]: I could tell it was him right away. He hadn’t changed at all. He was a little heftier, that was all.

[Víctor]: So we hugged and it was… it was like when we hugged when we said goodbye, back in Malvinas. But this time we were coming back together.

And with all of that emotion, well, I don’t know, we broke down. Right away.

[Gisela]: Rena had prepared everything. He had painted the house and made a new parrilla [a kind of iron grill used widely in Argentina].

[Jorge Luis]: It was a brand new parrilla. The cement was still drying in some places.

[Gisela]: And there is a video of the reunion, which is a home video that Rena and his family made. And I watched it.

(HOME VIDEO SOUNDBITE)

[Víctor]: Who wants mate? Who else wants mate?

[Gisela]: When I watch the video I realize that Rena is an unassuming guy. He has a really modest house. He’s a soldier, and then here comes this lieutenant! In other words, he’s this guy who has a different rank, a higher up, and everything that entails. So he did everything he could to be a good host for him.

[Víctor]: So we had an amazing day. It was a beautiful day.

[Gisela]: And before leaving Rena’s house, Reyes showed him a gift he’d bought thinking about the holy card Rena gave him in that final day, 29 years earlier.

[Jorge Luis]: I bought two painted statues of the Virgin of Luján that were about 45, 50 centimeters –pretty big. And we wrote down his name on one and my name on the other, and I left the one with my name with him and I kept the one with his name.

[Daniel]: And finally they had the asado?

[Gisela]: Yes. And after so many years of silence and conflicting emotions… because the veterans of the war in Malvinas lost a lot. For more than 29 years Reyes thought he had lost that person who was one of the few people who knew exactly what he had been through during the war.

At least they were able to enjoy that asado they had promised each other.

[Daniel]: That’s no small thing, don’t you think?

[Gisela]: Not at all. That day, with all of that backstory, they gained something enormous.

[Daniel]: This story was produced by Gisela Ederle and Javier Lucero. Gisela is a journalist in Buenos Aires and works at the Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento radio station. Javier works at Radio Universidad de Río de Cuarto and Radio Río Cuarto, in the province of Córdoba. Jorge Reyes’ book was eventually published under the title “Malvinas. Vinieron y les presentamos batalla”. [Malvinas. They came and we met them in battle]

We’d also like to thank Gabriel Pasquini, Javier Trimboli, Gonzalo Arechaga, Osvaldo Daniele, and Facundo Pérez Toro from the Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia Austral.

This story was edited by Luis Trelles, Camila Segura, Silvia Viñas and by me. Mixing and sound design are by Martina Castro and Andrés Azpiri. The music is by Luis Maurette.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Jorge Caraballo, Remy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Mosley, Ana Prieto, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas. Carolina Guerrero is our CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg Pro.

Do you follow us on Instagram? We want to follow you back. Publish in one of your stories a video of you listening to Radio Ambulante or recommending the podcast to your friends and tag us as @radioambulante. Today we will follow back the accounts who mention us. Remember: @radioambulante in Instagram. Thanks!

To hear more episodes and learn more about this story, visit our web page, radioambulante.org.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.