A Superpower | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

[Daniel]: Let’s start with this person:

[Jeanne Montalvo]: Hello. My name is Jeanne Montalvo. I am a producer at Futuro Media and a sound engineer.

[Daniel]: And with a question:

[Daniel]: When people ask where you’re from, how do you answer?

[Jeanne]: It’s a loaded question that, as a child of immigrants, you’re always dealing with what does it even mean. But I always say that my parents are Dominican and I was born here. That’s the easiest way to answer that question.

[Daniel]: By “here,” Jeanne refers to the United States. She was born in Oregon in 1981, and at the age of six, she moved to Alabama, a state in the south of the country. Specifically to Brewton, a town of almost six thousand people, where there were only 19 Hispanic people at the time. Four of whom were her family. So Jeanne grew up between two languages: outside, English, and at home, Spanish.

I know what it feels like to grow up like this. My family also immigrated to Alabama, in our case from Peru, when I was three years old, and we also became one of the few Latino families in our neighborhood. Speaking Spanish outside the walls of my home felt like speaking Esperanto or a language from another world. My family’s language was like a secret, intimate language…

But I adapted, Jeanne adapted, and we know that thousands of children adapt every year. We are like sponges at that age, and switching between languages is as easy as switching clothes.

So in 2017, when Jeanne had Martín, her first child, she didn’t think much about it. Her husband Ernesto is Peruvian, so they both took it for granted…

[Jeanne]: I would like to say that we had a conversation at the table stating, “OK, let’s speak Spanish to our children.” But since we both speak Spanish at home and we have a lot of Latino friends too, we didn’t sit down and say, “Let’s do this.” It was kind of natural, right? So that was the idea, that we were going to speak and eventually he was going to go to school, he was going to learn English.

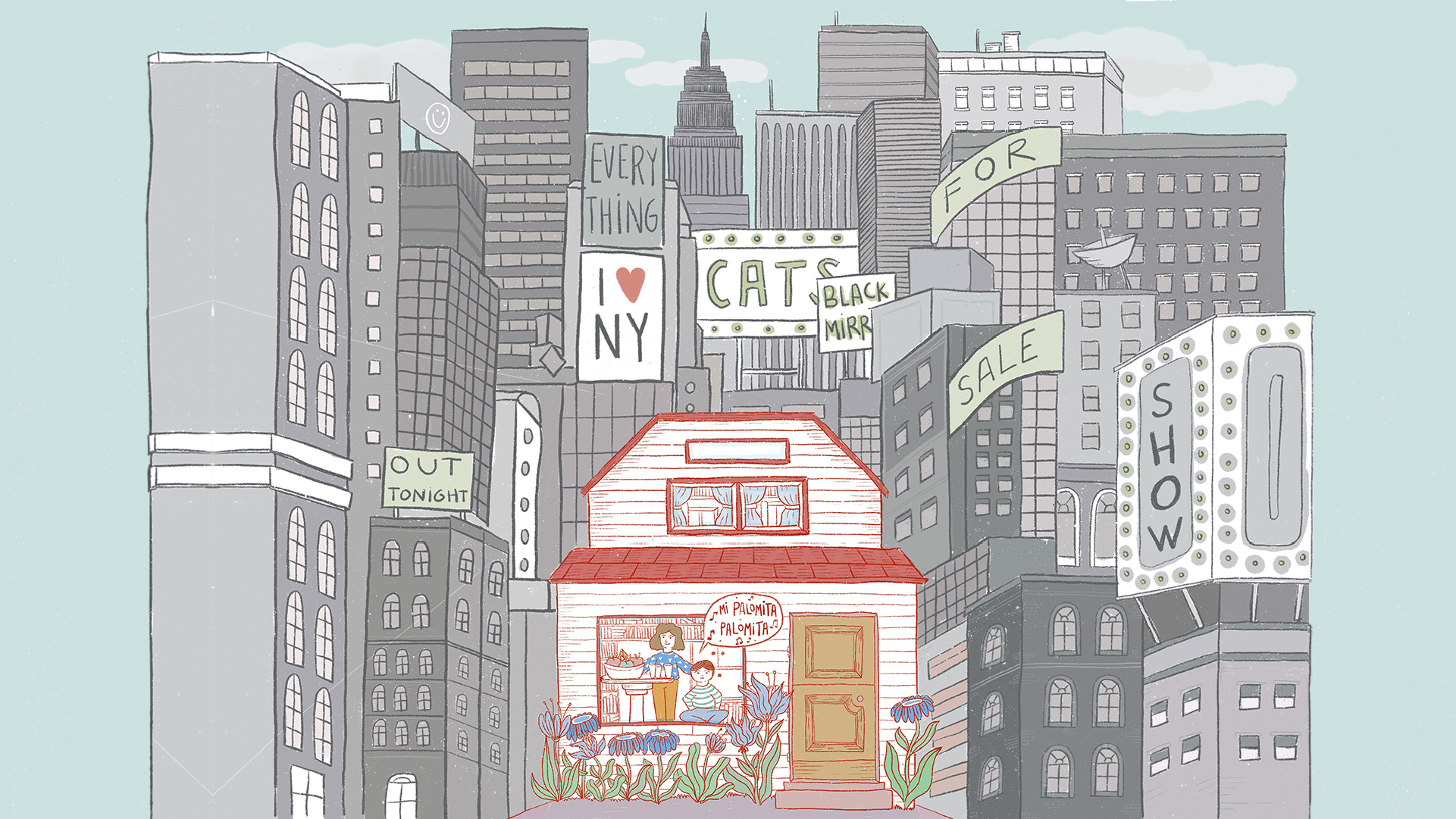

[Daniel]: By then, Jeanne and her husband were living in Queens, New York, a very different place from the town where she grew up. In Queens you can hear half a dozen languages if you walk down the street for a while. It is an area of the city where you can find daycare centers that are bilingual or even exclusively in Spanish.

[Jeanne]: We chose to take him to a school in the city that had full Spanish immersion, because we said, “Well, come on, let him have a solid base,” because I already went through all that and I know there comes a stage where he won’t want to speak Spanish. Let him get a solid base when he is young and we’ll deal with the rest later. It’s like we don’t worry about what comes afterward.

[Daniel]: Martín entered that nursery in 2019, when he was two years old. And everything was going as expected, until March 2020, when the pandemic arrived…

[Jeanne]: We had a plan and it didn’t turn out as we had imagined at all.

[Daniel]: Suddenly, disconnected from the outside world, what was so natural for Jeanne stopped being natural for her son. And this led her on a search that revealed a dark past of the multicultural city that is today New York.

We’ll be back.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Jeanne Montalvo continues the story.

[Archive soundbite, baby sounds]

[Jeanne]: As I was telling you, since Martín was born, my husband and I started speaking to him in Spanish.

[Archive soundbite, video with Martín]

[Jeanne]: And everything was going well. Martín spoke Spanish perfectly.

[Archive soundbite]

[Martín]: You’re falling asleep now, you’re falling asleep now, you’re falling asleep now…

[Jeanne]: Bravo, Martín, what a beautiful song!

[Ernesto]: Beautiful song.

[Jeanne]: But nothing prepared us for what this this would mean in the middle of a pandemic and a lockdown.

Martín was two and a half years old and, as far as he knew, the world was in Spanish. He not only spoke Spanish with us, but also at the kindergarten Zoom classes and in the video calls with his grandparents.

At the end of 2020, our second daughter, Isabel, was due to arrive, and the idea of the four of us living in a small apartment was stressful. Plus we wanted a quieter life for both of us, so we decided to move to the suburbs of New York.

It took us a while to get used to being there. But once the COVID vaccines arrived, we decided, in February 2021, that it was time for Martín to go out and interact in person with other children his age.

He was three and a half years old, and at age five he would start kindergarten. We knew that by state law, once Martín was in a public kindergarten, he could access bilingual classes or receive certain types of support in Spanish. But in the meantime, we had to find a daycare for him. The vast majority in our suburb were completely in English, and that was fine with us, because we wanted him to learn English before starting kindergarten.

So we did what many bilingual parents have done for generations: we enrolled him in an English-speaking daycare. It was a small class, with only eight children. We thought it was perfect for Martín, who has a lot of energy and is very restless.

At first, we sent him just two days a week, then three, and two months later he started going full time. We didn’t want him to have such an abrupt transition after being home for so long. But only two weeks after going full time, we were called in for a meeting. It was a Friday. The director and Martín’s teacher wanted to talk to us.

This is the daycare director when we start the meeting:

[Archive soundbite]

[Director]: And we have… we want to set Martín up for success. And we feel at this point we’re not. So we need help and support. We have some observations that we’ve been doing before we get started.

[Jeanne]: She began by saying that she wanted the best for Martín and that they needed our support with some things they had noticed.

She told us that Martín was pushing and hitting his classmates. They didn’t think it was aggression, but that it seemed to be his way of communicating. But, since the classrooms had cameras that all parents had access to, this could become a problem. At first, we listened to her without saying much, until she added one more concern, one that seemed very strange to us: That Martín was humming.

[Archive soundbite]

[Jeanne]: We both hum.

[Ernesto]: All the time. We all do. She’s a sound engineer. I’m a music producer. That’s just natural. That’s home. That’s… that’s how home works.

[Jeanne]: We told her that we both hum all the time, that I am a sound engineer and my husband is a music producer. That’s how it is at home; we all hum. We also told her that Martín usually does it when he is happy, or also to relax. Which I also did when I was little. We were laughing a little about the situation, but, of course, we still didn’t understand why this could be a problem. So Ernesto asked them directly:

[Archive soundbite]

[Ernesto]: Was that a concern, though?

[Jeanne]: Yeah. Was the humming something to worry about?

[Archive soundbite]

[Director]: I’ve never had a child do that, have you? And we both worked in this field for years. Okay. So that was like, huh… Because children on the spectrum do that.

[Jeanne]: She told us that she had never seen that in any child despite having worked for years in this field, and that it caught her attention because that is one of the things that children who are on the autism spectrum do…

[Archive soundbite]

[Ernesto]: Right. So I guess we’re on the spectrum.

[Jeanne]: “Ah, so maybe we are on the spectrum too,” Ernesto said.

It was something we had never considered. Nothing about Martín’s behavior or any of his medical checkups since he was a baby had indicated to us that this could be happening. And it also seemed very hasty to reach that conclusion. He hadn’t spent enough time in daycare, and besides, he was still too young for a serious diagnosis.

It was clear to us that the problem was the language and the way they were handling it. He simply did not understand English, and even though when we first went to that daycare we explained this explicitly, they assured us that they were trained to teach children who did not know English.

And, yes, our son has always had a hard time with change. He takes longer to adjust to things. And that, as we said, was a turbulent time. I told the director that I believed his behavior was probably related to the language barrier, not having any other bilingual classmates, and the consequences of a pandemic. And I added that, at his previous daycare—which was in Spanish—he had done well. Yes, at first he had started out very restless, but over time, he got better. Maybe it was too early to pass judgment.

The daycare’s solution was to put us on a “behavior plan.” It involved implementing specific techniques and phrases at home, and monitoring how much he could progress in a little less than a month. When we finished reading it, we reminded them that we already had a 10-day trip planned and told them that progress was going to be slower. Instead of a month, minus the travel, Martín would have only a little more than a week to progress. And I also explained that Martín has always needed time and patience in his development.

[Archive soundbite]

[Jeanne]: He’s always been later to milestones. And he walked late. He talked late like so. That’s why I’m saying like, okay, a week is not really enough time to evaluate if he’s going to make changes because the running took a while.

I told them that one week was not going to be enough.

[Archive soundbite, ambient farewell sounds from a meeting with the director].

We left that meeting frustrated. I, on the one hand, was burdened with doubts: Was there something we weren’t noticing? Were we doing what was best for Martín? Was this happening to us because he didn’t speak English? Was our decision hurting him?

That weekend, we spoke with two child psychologists, in addition to the pediatrician who had seen him those days. The consensus was that Martín was acting that way because he couldn’t communicate with the other children, and this behavior was his way of communicating. Maybe it wasn’t the best way, but it was the only way he knew at three and a half years old.

That Monday, we received another call from the daycare. They wanted us to come pick him up because they couldn’t deal with him that day. According to them, he was too restless.

There we confirmed that they didn’t want to help him the way he needed and that they didn’t want us there. It was evident that this was not going to work. I took him with me that day. And the next morning, Ernesto and I returned to inform the director that Martín would not return to that place.

But instead of this being a devastating moment, we were sure of what we were doing.

We knew that Martín’s ability to learn or follow directions was not based on his ability to speak English. He reminded me of what Sofía Vergara once said in Modern Family:

[Archive soundbite, Modern Family]

[Sofía Vergara]: Do you know how frustrating it is to have to translate everything in my head before I say it? Do you know how smart I am in Spanish?

[Jeanne]: Do you have any idea how frustrating it is to have to translate everything in my head before I say it? Do you know how smart I am when I speak Spanish?

Our decision to take Martín out of daycare still scared us, but it was the only option we had.

There was still a year and a half before he could start kindergarten, where they could help him with bilingual methodologies, so we needed a new daycare. One where he could learn English. We looked for one close to our house, and he started when we returned from the trip. We had to work, so we made the decision quickly. Now we just had to wait and see how he did in this one.

Meanwhile, I became obsessed with the topic of bilingual education in New York, and the following year, when I listened to an episode of The Bowery Boys, a podcast about the city’s history, I was struck by something they mentioned:

[Archive soundbite, Bowery Boys]

[Bowery Boys]: The New York State Chamber of Commerce took aim at Puerto Rican children, commissioning intelligence tests, then determining that Puerto Rican children were subnormal and would, quote, deteriorate standards already so seriously impaired by mass immigration…

[Jeanne]: They said that in 1935 the New York State Chamber of Commerce had commissioned intelligence tests to be done on Puerto Rican children. They had done tests and determined that—and get this—they were subnormal. Furthermore, they added that these children, and I quote, “would deteriorate standards already so seriously impaired by the mass immigration of populations with the lowest levels of many nations.”

I could not believe it. It was mind-blowing to me that something like that had ever existed. But, at the same time, understanding the past always helps us deal with the present and, in my case, prepare for the future. So I looked up everything I could about the study. I started reading about what they did and what they proposed with the results they obtained. They had conducted group IQ tests on 240 children between the ages of 9 and 16 at a specific school in Spanish Harlem, an area of Manhattan also known as “El Barrio,” where many Puerto Ricans lived.

More than half of the students—129 of them, to be exact—were evaluated using a test with instructions in English. Additionally, they were given only 20 minutes to complete it, instead of the half hour it takes. Those results were compared with the results of a very different control group—larger, from schools in wealthy neighborhoods across the state. And that is how they came to the conclusion that they were “subnormal.” Unbelievable.

Those who know a little about the history of New York know that the city has been home to waves of migration coming from all over the world. This has been the case for more than a century, when Ellis Island opened in 1892. Germans, Irish, Italians and Poles, among others, began to arrive seeking a better quality of life. And, together with them, in the middle of the Great Depression of ’29, the city also began to receive Spanish-speaking immigrants, especially from Puerto Rico.

It is nothing new, then, that New York receives people who speak different languages. However, from at least 1918 to 1964, New York public schools used to evaluate students’ IQs based on group tests given only in English. The exams were biased not just because of this, but because you could answer a question wrong simply because you didn’t know the culture, the history… because it was asking you something you had never seen in your life. They did not take into account the context, where each student came from. It’s as if these exams were designed to make children fail.

And here I was, 90 years later, getting a speech not very different from that one, at my son’s daycare. That because of a language barrier, he was different. As if in almost a century very little progress had been made. I wanted to know more about the educational system that was excluding my son, so I spoke to this person:

[Aida Nevarez-La Torre]: My name is Aida Nevarez-La Torre. I was born and raised in Puerto Rico.

[Jeanne]: Aida has a PhD in Education, is the dean at Fordham University in New York, and is specialized in multilingual education.

[Aida]: The concept of intelligence was developed in Europe. One of the first was Binet, a Frenchman.

[Jeanne]: Alfred Binet, a French psychologist who in 1905 collaborated with his colleague Theodore Simon to develop a series of tests to assess intelligence in children.

[Aida]: The intelligence test is an instrument to capture how the human brain thinks, how we learn. What a human being’s capacity is for learning.

[Jeanne]: A decade later, Stanford University adapted the Binet test for use in the United States. Soon, the Stanford team was called by the Army, which had a particular interest.

[Aida]: The First World War happens. We must determine who can make the best soldiers. They must pass some tests, right?

[Jeanne]: Then the so-called “Army-Alpha Test” was created, which evaluated verbal and numerical ability, the ability to follow directions, and knowledge of information. All in written form and in English.

Shorter versions of these tests were used in the 1935 study of Puerto Rican children. In fact, to this day, a version of this test is still used in public schools in this country.

Aida told me that, in addition to using these tests to determine who could make “the best soldier,” there were other objectives:

[Aida]: The United States was experiencing one of its biggest migration phases. And the question is not only who do we send, who is the best soldier we can send to war, but, hey, should we as a nation accept all types of migrants? How can we limit the entry into this country of people who are not as intelligent as the majority of people already in our country?

[Jeanne]: It was a time when it was debated whether or not Puerto Rico should become a state like any other in the country. With this study, it was concluded not only that the city was harmed by the migration of Puerto Ricans and that—and here I paraphrase— “the majority of these children will not be able to adapt to civilization and are delaying progress.” It was also suggested that the proposal for Puerto Rico to become a state should be suspended.

But, in addition to all this, none of these tests clearly measure supposed intelligence.

[Aida]: When these types of tests are given, what is really being tested? What is tested is the student’s knowledge of the language and the student’s knowledge of the culture represented on that exam.

We now understand, after all these years, that intelligence is much more complex. And right now, psychologists and educators understand that there is more than one intelligence: there is verbal intelligence, there is physical intelligence, there is emotional intelligence.

[Jeanne]: As a journalist and as a mother, it was devastating to realize that children were used to justify that a certain type of population did not deserve to migrate to this country. Kids who just wanted to learn and grow, and who never did anything to anyone except exist. Exist in Spanish.

Meanwhile, no effort was being made at the state or federal level to ensure that these children could receive support in their native language. The only alternative left was to adapt to what was there. And those who couldn’t adapt, who didn’t do well on IQ tests or who didn’t do well in class because of the language, were sent to academic leveling classes. That’s what today would be considered special education, such as classes for children who need individual help. And although these classes were a resource that many children needed, they also became a kind of funnel to put children considered “problematic” or, simply, those who did not understand English. And many teachers recommended it either because it was easier or because it was the only option they had learned.

[Aida]: The teacher was no doubt trained to teach monolingual students in English. There was no training given on how language is acquired, no education was given for the teacher to understand how a student can be taught even if the student does not speak the teacher’s language.

[Jeanne]: Instead of considering language as a factor in why a child may have difficulty learning, it was concluded that he or she needed special education. Sadly, this was starting to sound all too familiar.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Jeanne Montalvo continues the story.

[Jeanne]: I needed to understand how all this was related to me, what had happened after the ‘30s, what had improved and what had not. What my son could expect when he formally entered the New York State educational system.

Aida told me that in the ‘50s, children who did not speak English were put in classes to learn only English.

[Aida]: So this type of student was put in a classroom and the entire day was spent learning English, but they did not learn science or math.

[Jeanne]: It is a system that began to be used in the city’s public schools. Once the teacher considered that the student knew English—which could take a couple of years—the child returned to the classroom and joined his classmates…

[Aida]: And what happens? After a year, after two years in that kind of classroom, they can understand what the teacher is saying, but they are two years behind because they missed instruction in math, in science, in social studies.

[Jeanne]: For these children, it was simply impossible to be at the same level as their other classmates. And since many teachers were not trained for these situations…

[Aida]: And if that teacher does not understand that lag, the teacher is going to judge that student as having mental learning problems because he or she learned English but cannot write an essay in English, they were never taught to write a composition in English in terms of structure, format of what is expected, paragraph one, paragraph two…. he or she, of course, can’t do it.

[Jeanne]: This system also discouraged students from staying in school.

[Aida]: There are studies proving that many of these students decide to leave school because they are intelligent and what happens in that type of classroom is very boring. How can it be that I spend hour after hour repeating words, writing. I had to write them 20 times? Better to leave school, find a job and help my family financially. And on my own, then I can learn something and use that to improve my life in this country.

[Jeanne]: It seems logical to me that those children reacted that way.

New York had never received as many Puerto Ricans as at that time, after World War II. From about 13,000 in 1945, by the mid-60s, there were almost a million Puerto Ricans living in the city. And in the middle of this great migration, certain media outlets began to call it “the Puerto Rican problem.

What they said was similar to the conclusion of the ’35 study: that the city did not have enough resources for Puerto Ricans, who not only did not speak English but were also less intelligent.

However, during the same years of that hate campaign, the city’s Board of Education began to promote changes to improve the education that Puerto Rican children received.

In 1953, they began an investigation that they called “The Puerto Rican Study.” In this case, instead of using IQ tests, they did everything. They visited schools, reviewed previous supervisions, organized meetings with administrators, observed classes, held workshops, tested pilot classes and new teaching methods for bilingual students. All of this was done over four years in different schools and in classes from first grade to high school. After reaching conclusions, they proposed a new learning system.

They were teaching techniques and materials specifically designed for bilingual students. And the way the study talked about Puerto Rican children was very different from what the media said.

When I read this report, I was a little shocked. There were books, pamphlets, pages and pages of techniques to improve ways of raising bilingual children. Later I found out that the study had cost 1 million dollars, equivalent today to about 12 million. But none of this—nothing! —had been put into practice. The changes would be achieved later and would be the result of a struggle. And if anything changed for the education of Latino children in New York, it would be largely thanks to a Puerto Rican woman named Antonia Pantoja.

[Archive soundbite]

[Antonia Pantoja]: We started to learn from the youth. What was happening to them in the schools.

[Jeanne]: Here she appears in a documentary from 2008. She says that they began to listen to what young people said about their experience in schools and the way they were discriminated against.

Pantoja was born in Puerto Rico, came to New York in 1944, and died in the city in 2002. She led a fight for equal rights for Puerto Ricans, not only for the preservation of Puerto Rican culture, but also for access to bilingual education. This turned her into an activist, and in the 1960s she created Aspira, an organization founded as a place for Puerto Rican children to receive after-school support so they could better prepare to go to college.

Antonia was convinced that it was the language barrier that prevented Puerto Rican children from learning the content for their grade level and that, for this reason, they stopped going to school. Something we now know for sure. And what she proposed in response to that problem was very simple, but revolutionary:

[Archive soundbite]

[Antonia]: If there’s a law that says that I have to take my children to school, then I can accuse you as an institution where I have brought my children if you don’t teach them.

[Jeanne]: If the law requires us to send our children to school, then we can report any educational institution that is not educating them.

Thus, in 1972, Aspira and the newly founded Puerto Rican Legal Defense Fund, a Puerto Rican civil rights organization, sued the New York City Board of Education.

They argued that, because of the language in which classes were taught, many Puerto Rican children with limited English proficiency were prevented from fully participating in public school. And what both organizations were asking for was, basically, equal educational opportunities for them.

After two years, the city reached an agreement with these organizations and decreed the right of every non-English speaking student to receive special language assistance. And while the decree suggested some ways to provide that special help, it did not specify a detailed program of how it would be done. However, this was one of many lawsuits of this type brought all over the country in the 1970s that led to legislation at the national level. It was what laid the foundations for what we know today as bilingual education.

OK, but how much did Puerto Rico have to do with my Dominican-American upbringing in Alabama and that of my Dominican-Peruvian-American children? Spanish, of course. Having a common language meant that Puerto Ricans were fighting for all the Spanish-speakers in New York. Because, eventually and to this day, the state and the city would receive immigrants from many other Spanish-speaking places: Dominicans, Mexicans, Central Americans, South Americans. After English, Spanish has become the most spoken language in this region, with almost three million speakers.

[Jeanne]: And so the Spanish-speakers who fought for bilingual education created a domino effect that benefited many more people.

New York State public schools today have a population of over 260,000 students who speak more than 200 languages. According to the Board of Education’s website, all teachers, from kindergarten through high school, must be trained to support students who are learning English as they acquire content knowledge.

However, in daycare, we as parents still have to be vigilant because the requirements for teachers are different. Even if your toddler’s teacher is good at taking care of a 3-year-old, he or she may not be trained to work with bilingual children.

[Archive soundbite, video with Martín]

[Ernesto]: Martín!

[Jeanne]: Hello, Martín!… They are the same…

In September 2022, Martín started kindergarten, finally in the public school system. Because we said in the questionnaire that we spoke another language at home, they evaluated him on his knowledge of English.

[Archive soundbite, video with Martín]

[Martín]: I did a lot of things. I did a test, a talk test.

[Jeanne]: Martín is in a school district with a teacher of ENL, English as a New Language. Based on his test results, he receives 3 hours of support a week, in addition to the classes that all the other children receive.

Today, bilingual education works in various ways in New York State. There are school districts that teach in both languages at the same time, others that have what is called “transitional language instruction”—something similar to what they did in the ‘50s—where they teach English separately, and there are others that have programs like Martín’s. In our school district, which is in the suburbs, Martín’s ENL teacher comes into his classroom and works in tandem with the classroom teacher. Martín has been doing this for a year and a half now, and this was what he needed.

[Archive soundbite, video with Martín]

[Martín]: Now I really how to speak. I know how to speak the two of them.

[Jeanne]: He says he now knows how to speak both languages.

When kindergarten started, the ENL teacher recommended that we continue what we were doing. “The better Martín speaks Spanish, the better he will speak English,” he told us.

All the stress I had felt for the last year and a half began to fade away. We knew that he was in a place now where he would get support.

And yes, now, after being in a second, better-prepared daycare and in this new school, Martín speaks English and Spanish. Although he has gotten mega-ultra-specific about when and where we speak either language.

[Archive soundbite, video with Martín]

[Jeanne]: Do you want to speak English at home?

[Martín]: Because I don’t always like it.

[Jeanne]: You don’t like it? But you have to learn to read in Spanish… in English.

[Martín]: No, but at school it is in English, but at home it is in Spanish, not English. That’s why I always speak in Spanish here.

[Jeanne]: But how will you learn to read in English, then?

[Martín]: At school. Not here. Only in Spanish.

[Jeanne]: But I want to help you, Martín.

[Martín]: No, only if someone speaks English.

[Jeanne]: So I can’t. Mommy can’t speak English with you?

[Martín]: No. And neither can daddy. And neither can the gordita either. Only at school.

[Jeanne]: And I understand him, because I don’t know about you, my bilingual friends, but for me it is very strange to speak in Spanish or English with certain people. I can’t speak English with my husband, but neither can I speak Spanish with my brother. And the same thing happens to me now with my children: It feels very strange if I don’t speak Spanish with them.

Almost like the method known as one parent, one language that is used to teach your child two languages at the same time, Martín now associates Spanish with home and English with school. He even goes to the extreme of being adamantly opposed to us watching movies in English at home.

For me, in my time, there wasn’t the option to change the language or add Spanish subtitles to TV series and movies, so it has been very strange to have to watch every Disney movie in Spanish again.

For example, I would love to sing “Let it Go” from Frozen… Let it Go, Let it Go… in English…

But I had to learn it all in Spanish so that I could sing it with Martín and Isabel.

[Archive soundbite]

[Isabel]: I am free!…

[Jeanne]: This process has been difficult for me too, because during my adolescence, English took over my life. It became my dominant language. At home, every day I consciously choose to speak in Spanish. Anyone who has to switch between languages knows that this can be exhausting. But I do it because I want to maintain my own fluency and because I want my children to speak it naturally. As I told you at the beginning of this story, I am prepared for the day when they tell me, “I don’t want to speak Spanish.” Because I’m sure that day can come, and if it happens… well, that’s okay.

[Archive soundbite, ambi sound with Isabel]

[Jeanne]: In the middle of this whole process with Martín, my daughter, who spoke only Spanish at home with us, began, at age 2, going to a daycare center where they only spoke English. I hadn’t even realized that she spoke English outside our home.

[Archive soundbite, Isabel speaking English]

[Jeanne]: Because at home I only hear her speak in Spanish.

[Archive soundbite, Isabel speaking English]

[Jeanne]: I never thought it would be so fast, that she would start alternating between the two languages.

Maybe that’s how it would have been with Martín in that nursery given enough time, but they simply didn’t want to or didn’t know how to do it. And through this process, I have learned that you have to advocate for your child and that we owe bilingual education as it exists today in New York to a group of Spanish-speakers who fought for it. And to them I say thank you.

I am convinced that bilingualism is one of the best gifts I can give my children. There are more books to read, movies to watch, and more of the world to absorb. Many generations like mine have done it. As my parents did with me. This is me at 3 years old, singing “Palomita” with my mom.

[Archive soundbite, Jeanne singing “Palomita”]

And these are Isabel and Martín singing the same song.

[Archive soundbite, Isabel and Martín singing “Palomita”]

[Jeanne]: Bilingualism is our super-power.

[Daniel]: It seemed particularly relevant to us to do this story, because in the last two years, more than 150,000 immigrants have arrived in New York, many from Latin America. If you live in New York, it is important to know that by law, public schools across the state must provide language assistance to all children. If this does not happen, parents have the right to ask for help. The official New York State website has resources in more than 30 languages that explain these and other rights.

Our listener, Heidi Yorkshire, will read the credits of this story as part of the benefits of being a supporter.

[Heidi Yorkshire]: I am proud to be a part of Wanderers, the membership program of Radio Ambulante Estudios. I support them because their journalism is amazing and helps me understand what is happening in Latin America. If you want to help them continue telling the stories of Latin America, visit Radio Ambulante dot org slash donate. Here are the credits for today’s episode.

Jeanne Montalvo is a senior producer at Futuro Studios and lives in New York. An English version of this story was published on the LatinoUSA podcast. If you want to listen to it, you can find it as Bilingual is My Superpower.

This story was produced by Jeanne Montalvo, Camila Segura and Natalia Sánchez Loayza. It was edited by Daniel Alarcón. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Ana Tuirán and Andrés Azpiri, with original music by Ana.

Special thanks to Gabriela Noriega for her help on this episode.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Andrés Azpiri, Adriana Bernal, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.