Editing War | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

🚨Latino communities are under attack in the United States. And while this is happening, independent media are losing funding. Telling our stories with rigor, dignity, and empathy has become essential. To keep doing it, we need your support. Join Deambulantes, our membership program. This journalism exists because people like you decide it matters. Our goal is for 5,000 people to support us before the end of the year. DONATE TODAY. Your contribution makes ALL the difference. Thank you in advance.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Hello, Ambulantes. Over the past year, we have worked tirelessly. We have produced more content than ever before: in 2025, we have published 30 episodes of Radio Ambulante and are halfway through our 15th season; in El hilo, in addition to our weekly coverage, we have published our first series: Amazonas adentro. There’s also our first video podcast in English, The Moment, and La Ruta del Sol, on Central, our series channel.

None of this happened by chance; it’s our commitment to keep moving forward. And none of this would have been possible without the support of listeners like you.

Today, 5,000 people support our work with their donations. To ensure our sustainability, we need another 5,000 to join us. We have done our part; now we ask you, if it is within your means, to help us.

Because together, we continue.

Go to radioambulante dot org diagonal donate. Every amount counts. And remember: if you are in the United States, your donations are tax deductible. Thank you very much! Here is the episode.

This is Radio Ambulante, I’m Daniel Alarcón.

I want to start with a question… How many times have you used Wikipedia? You know, the online encyclopedia. Count them up, just like that, without thinking too much… A hundred times, five hundred? Even more?

Ok… now, have you ever wondered who the people are behind the articles you’ve read there?

[Santiago]: I would describe Wikipedia as the largest repository of knowledge that exists today.

[Daniel]: Meet Santiago. And Oscar:

[Oscar]: It’s what was called the Tower of Babel. A kind of place to find all types of knowledge, not just from one culture, but from all cultures, in different languages.

[Daniel]: To be exact, 342 languages. Santiago and Oscar are Venezuelan and also two of the thousands of people around the world who write and correct the articles we read on Wikipedia. These people are called “Wikipedians” or “editors.” Oscar started doing it around 2005. And Santiago in 2014.

[Oscar]: A tab would appear that said “edit.” So you click on it and you see that you can basically change the letters.

[Santiago]: There isn’t really a barrier to entry at first. Anyone, literally anyone, can edit.

[Daniel]: It’s easy to become an editor, but it’s not easy to do it well. Especially if you’re a beginner. To give you an example: when he was still a novice, Oscar wrote the Spanish entry for Oasis, the rock band.

[Santiago]: What I did was copy and paste from another Oasis fan page. So that was obviously plagiarism where I was placing information that had no sources. And there I obviously got scolded because other users with much more experience said something like “look, you’re doing this wrong for this reason.” And at first I was like “what?”, I didn’t understand.

[Daniel]: The thing is, editing well is a whole art. So much so that Wikipedia has a tutorial with the main rules that editors should follow. Santiago read me a fragment of that tutorial.

[Santiago]: “Be bold in creating, translating and modifying articles because the beauty of editing is that although perfection is pursued, it’s not required to achieve it. Don’t be afraid to edit for fear of turning everything upside down. All previous versions of articles are saved, so there’s no way you can accidentally mess up Wikipedia or irreparably destroy its content. That’s why remember that everything you write here will pass into posterity.”

[Daniel]: It’s exciting. Like an invitation to be part of something enormous. And this is exactly what Santiago and Oscar liked from the beginning: joining the effort to build a great compendium of knowledge.

[Santiago]: Wikipedia is based on that: Each person who contributes a grain of sand and who finds one error or another or who knows about something, is interested in something and wants to write, wants to create, wants to—you know?—maintain…

[Daniel]: Take care of that Tower of Babel that Oscar mentioned before. It’s not a perfect effort: the encyclopedia has incomplete, superficial, promotional articles, with errors or that are attacked by what in the Wikipedia world are called vandals: those who remove or modify information on purpose, who insult for fun and who even write fiction and pass it off as truth.

[Oscar]: Just as there are people who want to build the encyclopedia, there are “n” number of people who want to destroy it. And they look for any type of methods to vandalize it or create problems.

[Daniel]: In the midst of that chaos, editing and editing, Oscar and Santiago became friends. They were like two little ants: hardworking, anonymous, insignificant. And also idealistic. They believed in Wikipedia’s power to change the lives of Venezuelans.

[Santiago]: In the context of the Venezuelan crisis—poor internet penetration, educational crisis and so on—Wikipedia is a fundamental tool for access to information, to education. It still needs to improve quite a bit. But undoubtedly when you want to consult about history, biology, chemistry and so on, one of the first sources to consult is Wikipedia.

[Daniel]: And that’s why they wanted the tower they were helping to build to reach higher and higher. But then Venezuela began to collapse around them. Oscar and Santiago began to edit about what was happening in their country. And that work, for which no one paid them and which they did in their free time, began to be seen as a threat.

[Oscar]: Maybe we didn’t understand what country we were in until what happened to us happened to us.

[Daniel]: Mexican journalist Pablo Argüelles continues telling us.

[Pablo Argüelles]: Ok, let’s go to 2011. By then Wikipedia had just turned ten years old and a small group of encyclopedia editors, all Venezuelan, met one day in a classroom at the Central University of Venezuela, in Caracas. Among them was Oscar.

[Oscar]: I think that despite having different backgrounds and upbringings and very different ways of life, perhaps, from one another, I think what united us was that love of free knowledge and trying to express that in something that would transcend the free encyclopedia.

[Pablo]: Oscar and the other editors had initially met online, editing the encyclopedia. But now, gathered in the university classroom, they wanted to make a leap into the real world. That meeting was the first of many. A year later, in 2012, they ended up creating a non-profit association, Wikimedia Venezuela, made up of pure volunteers. Their goal was to train new editors and bring more knowledge about Venezuela to Wikipedia.

[Oscar]: Any information obviously truthful, relevant, of interest, we sought to have that information within Wikipedia.

[Pablo]: The organization very quickly became Wikipedia’s representative in the country. Similar volunteer groups already existed in Argentina or Spain but they were much larger and with more resources. In its beginnings Wikimedia Venezuela was no more than a dozen members. It didn’t have a long-term plan. And let’s not even talk about money.

[Oscar]: There’s a very Venezuelan phrase that says “as it comes, we’ll see.”

[Pablo]: With that strategy, Oscar and his colleagues began to contact various public institutions.

[Oscar]: That. Universities, museums, libraries, ministries related to culture, the Ministry of Science and Technology…

[Pablo]: Those who could be considered the “official” guardians of knowledge about Venezuela. The idea was to train people from those institutions to write articles. In other words, they tried to convince them to release the information housed in their archives and bookstores and exhibitions and upload it to Wikipedia, for free.

[Oscar]: So we also appealed a little to nationalism in some sense that we want information about Venezuela, the culture, geography, gastronomy, everything about Venezuela to be well reflected. And for that we need to tell that story on Wikipedia. A person in Chile, a person in Spain is not going to come to narrate what happens in Venezuela.

[Pablo]: Slowly they gained allies, especially in universities. Now, Oscar and the Wikipedians also organized collective editing workshops, called “editathons.” They would get together with students, professors, even retirees, to write articles on some specific topic. One day it could be “Venezuelan artists” and another day “women scientists from Venezuela.” This meeting, according to Oscar, was quite a success.

[Oscar]: When we saw that reception we said we have to keep doing this type of events, we have to repeat this because people sort of resonate with them.

[Pablo]: And it was at one of those editathons, in 2016, that Oscar met Santiago. And it surprised him a lot.

[Oscar]: He was like a super Wikipedian who edited on everything, I’d say on all topics related to Venezuela.

[Santiago]: The topics about Venezuela were mostly history, well, politics, some biographies of both opposition and pro-government figures, movies, books, music too.

[Pablo]: In other words, Santiago was the perfect candidate to join Wikimedia Venezuela. And so he did. He began organizing editathons together with Oscar. There they not only taught how to create content, but also how to be a good editor. Because to write a good encyclopedia article you have to understand several things. First, what is a reliable source: books, academic research, press notes. In other words, backed and verified information. Oscar says it firmly: Wikipedia is not an opinion blog:

[Oscar]: It doesn’t exist to satisfy your political point of view or your religious point of view or whatever you have… Wikipedia, what it does mean is that you have to remove all those biases and follow the policies of relevance, of a policy called the neutral point of view.

[Pablo]: The neutral point of view, which forces you to include relevant points of view on a topic, to avoid bias. Here’s Santiago.

[Santiago]: It should be noted that not all points of view are equal. There are false balances, right? It’s not the same, to say, the consensus of the scientific community as flat-earthism.

[Pablo]: Now, achieving that neutrality is actually impossible.

[Santiago]: We all have our origins. We all have our biases, we’re not perfect, but one has to try to be the best, as balanced as possible.

[Pablo]: It’s an effort to be fair. It implies neutralizing your pride and accepting that you’re not on Wikipedia to win an argument. Because besides, ideally encyclopedia articles don’t have a single author: they evolve over time, with contributions and debates between editors. This is important: each encyclopedia article has its own discussion section, it’s like a forum where editors seek to reach consensus on the information presented in the text.

[Santiago]: Do you think the information should be removed? Well, why?

[Pablo]: If you think something is false or incomplete, you must verify it. And you must also be careful with the words you use: these could hide your own biases.

[Santiago]: Well, let’s change adjectives, change qualifiers, present it in another way.

[Pablo]: Clarity and precision are always sought.

[Santiago]: Ah, this is interesting! There’s another point of view, right? That means it can be complemented. So these are grays, these contrasts that one encounters and well, they’re completely valid.

[Pablo]: A good editor, then, cultivates an obsession with sources, nuances, consensus and cordiality in discussions. Now, this is the theory. But in the specific case of Oscar and Santiago, Venezuelan reality muddied everything.

[Oscar]: Basically over the years it became, let’s say, a little more difficult to achieve consensus.

[Pablo]: Because what was happening then—2014, 2015, 2016—awakened too many opinions and emotions among Venezuelan editors.

[Santiago]: Years and years of hyperinflation, scarcity, crime, censorship… an autocracy, in summary.

[Pablo]: It was such a conflictive situation that not taking a stance was very difficult. Both Santiago and Oscar had their political opinions, of course, but they were very careful not to reflect them in the encyclopedia. For them editing was not a form of political activism. But this only complicated their work.

[Oscar]: It was very difficult to be a judge and jury. And in many cases I said well, I can’t continue doing administrative actions on Venezuelan topics because I also didn’t feel capable of being totally neutral. So I let Spaniards, Mexicans, from other parts of the world, come to try to help us with editorial topics.

[Pablo]: And so we reach April 2017. A key moment for understanding Venezuela in recent years. The Supreme Court of Justice took powers away from the Legislative Assembly, which was then in opposition hands. The measure was seen as a coup d’état in favor of Nicolás Maduro’s government. And the people… took to the streets.

[Journalist]: Violent protests in Venezuela after more than a week of anti-government demonstrations…

[Oscar]: It was a situation of desperation, like the ship is sinking…

[Oscar]: …Or that you’re in a pot with water about to boil and you’re inside the pot. That’s how we felt. I think it was a collective situation.

[Woman]: They’re taking away our rights, come on, it can’t be like this, we want to march because we’re going hungry while they’re over there alive, like that, relaxed…

[Pablo]: For Oscar and Santiago it was about defending the little democracy they then had in Venezuela. So they spent April, May, June going out to march, each on their own. The repression against citizens was brutal: more than 5,500 people detained and hundreds dead. In those months, Santiago had his little ritual: he put on sunscreen, packed his arepas and also a plastic bottle with a sodium bicarbonate solution. To neutralize the police tear gas.

[Santiago]: I mean, I swallowed gas like there was no tomorrow. I mean quite a few, quite a few times.

[Pablo]: During those months Santiago uploaded photos of the protests to Wikipedia. In the articles he edited he was careful with his language, avoided words like regime or dictatorship or even qualifiers like a “big” march. Then, one rainy afternoon in late June he went out with some university classmates to protest again. And again they encountered tear gas bombs, riot police. The usual.

[Santiago]: We started crossing through streets that were lightly trafficked, because ideally, the safest thing is for you to go with a group of people. And finally, there was a block where they intercepted us. It was a motorized commission of the Bolivarian National Police, the PNB.

[Woman 1]: This is in front of the office, BOD Tower, El Rosal…

[Pablo]: From the surroundings several people were recording what was happening.

[Woman 1]: Look how they have the girls kneeling.

[Pablo]: The police made Santiago and his classmates kneel…

[Woman 1]: They’re so dirty…

[Pablo]: They took away their shoelaces, with them they tied their hands. And they started loading them into a white truck. And while they were doing it…

[Woman 2]: There are too many police…

[Pablo]: A cloud of tear gas began to envelop them.

[Woman 2]: Look how they close the…, with the gas there, so that they get a lot of gas… Girl, they can’t be so… really, look…

[Daniel]: The police took Santiago and his classmates away.

Let’s take a break, we’ll be right back.

[Daniel]: We’re back on Radio Ambulante. Pablo continues telling us.

[Pablo]: Santiago and his university classmates were taken to the Helicoide, a prison in Caracas with a very bad reputation, where according to the UN several human rights violations have been committed. That night the police took photos of them, and the next day they gave them toxicological tests and the prosecutor interrogated them. Then they were taken to the Palace of Justice for the hearing with the judge, but it was postponed. So they returned to prison and spent the night there. In this back and forth no one told them why they had been detained. They couldn’t communicate with their families and lawyers. They were isolated.

[Santiago]: I think there you feel like the weight of power. Or of the State. One feels small, you know?

[Pablo]: The next day they had the hearing. Santiago and his classmates were accused of public disorder, use of Molotov cocktails and attacks on police. As evidence, the government presented the objects the young men were carrying the day of the protest: helmets and gloves, a Venezuelan flag and the plastic bottle with the bicarbonate solution. Actually it wasn’t much.

[Santiago]: And then the defense, I mean, all the lawyers—who fortunately the Student Movement, families and everyone else brought—show all the inconsistency: “In fact, these kids should have been presented within 48 hours of their detention. This wasn’t complied with…” You see that you don’t have the same, like gasoline, you don’t have Molotov cocktails, you don’t have any of this. And there are contradictions in the testimony. I mean, a large amount of proof and evidence.

[Pablo]: That they weren’t guilty of the crimes they were being accused of. The judge ended up releasing Santiago and his classmates and a few days later, Santiago gave an interview on the radio and talked about his experience in prison. He did the same on the social network Reddit. There he had the same username as on Wikipedia, so it was easy to identify him on the encyclopedia. And although talking like that was perhaps exposing himself, he felt it was good for people to know more about what had been done to him. Meanwhile, inside him grew a great disillusionment with the country.

[Santiago]: I say, well, but nothing is going to change here. I mean, this is power for power’s sake. I don’t see this solution in the short term. I’m leaving.

[Pablo]: He decided he was going to migrate to Spain.

[Santiago]: I simply wanted to continue my life. I wanted to seek normality. I think that’s the best word to describe it.

[Pablo]: He began preparing all the papers to migrate. Months passed and in March 2018, he remembered the interview he gave on the radio after his arrest. He wanted to see it again so he searched his name on Google. But instead of the interview, he found a video on YouTube. In it appeared a photo of his identity card and this text:

[Santiago]: “Aruba authorities detained six occupants of a vessel with a Venezuelan flag after the seizure of 125 kilos of cocaine. The crew members, four Venezuelans and two Colombians, were placed at the disposal of the authorities.”

[Pablo]: And the worst part: The video said that Santiago was the intellectual author of the smuggling, owner of the drugs, investigated by the DEA and the Dutch police.

[Santiago]: How am I going to react? You know? Like… I mean, what do I do?

[Pablo]: It was something absurd and terrifying, because Santiago discovered the news…

[Santiago]: Santiago implicated in drug seizure. Santiago was betrayed by his partners in drug shipment. Santiago, owner of 125 kilos of cocaine confiscated in Aruba.

[Pablo]: …appeared on many other sites.

[Santiago]: Las Sanguijuelas de Venezuela, El Pajuo, Noticias 75, Venezuela día a día…

[Pablo]: One site even accused him of being an informant for SEBIN, the government’s intelligence services.

Santiago didn’t know who was behind the publications. He was unaware of the motive for the attacks, whether they were a threat, revenge or simply another of the many things that could happen to a Venezuelan at that time. The only sure thing was that very soon he would go to Spain and that he had to continue with his life. So he configured his email to receive alerts in case that type of news appeared again. And he tried to forget about everything. In August 2018, with all the migration documents ready, he got on a plane and left his country.

[Oscar]: And it wasn’t just him. I remember that several members of Wikimedia Venezuela left.

[Pablo]: Here’s Oscar again. He saw how several Wikipedians began to leave. To the United States, Peru, Argentina, Israel. For him, who stayed in Caracas, that exodus was a real brain drain.

[Oscar]: It hurts you, but inside, you say like well, they’re going to do better in another country because this country doesn’t give them the possibilities to develop.

[Pablo]: But this meant that Wikimedia Venezuela had fewer and fewer members in the country—about 6—to organize events, contact institutions, train editors… All while the country continued in turmoil. On January 10, 2019, Nicolás Maduro assumed the presidency of Venezuela for six more years. But Juan Guaidó, then the leader of the National Assembly, disavowed the results and proclaimed himself interim president of the Republic.

[Oscar]: And people went, well, many users went directly to place him in Wikipedia articles. But just as some arrived, others came to say “no, this is not the president, the president is still Nicolás Maduro” and that’s where it started.

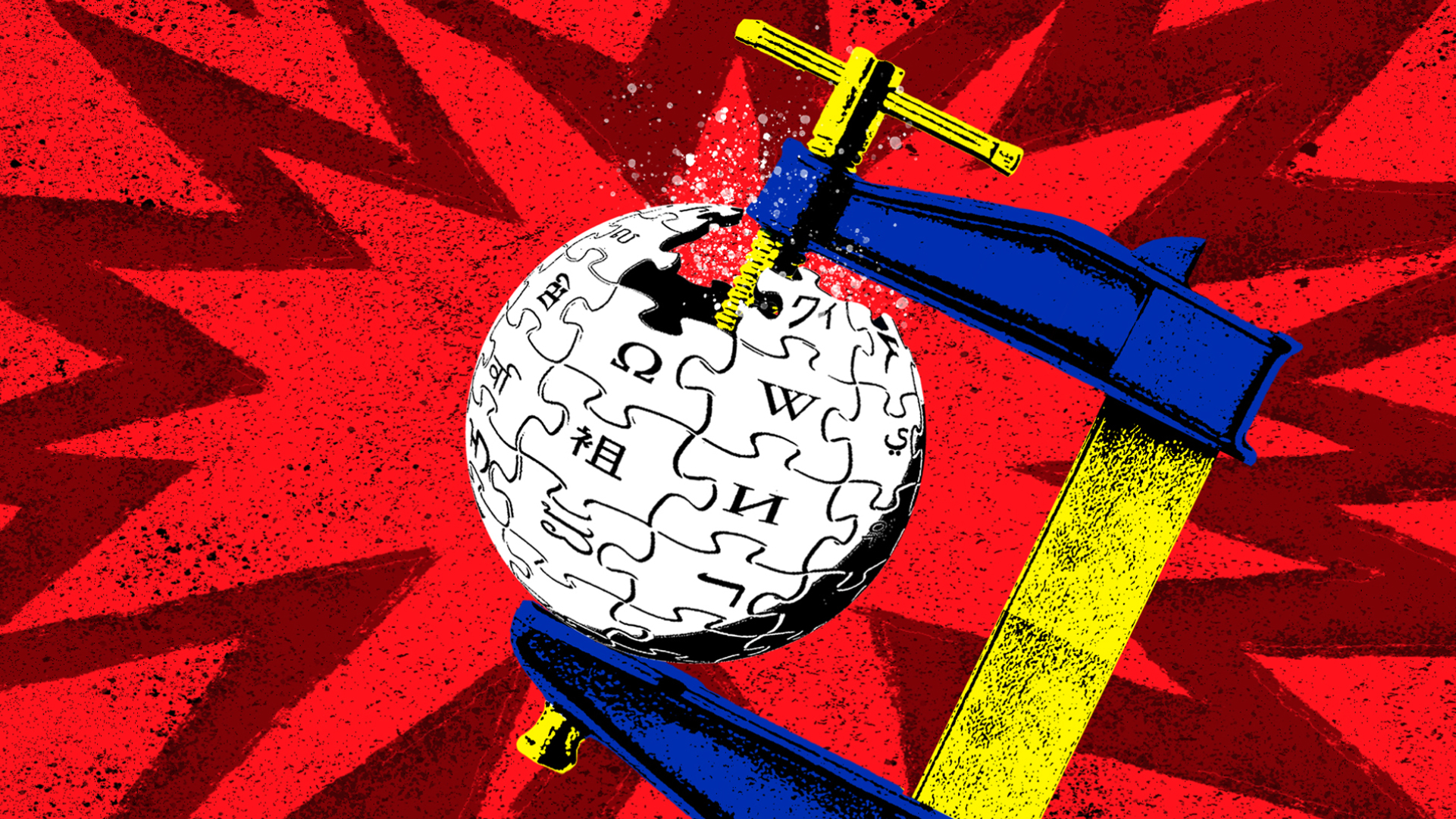

[Pablo]: That: an edit war. “Maduro is president; no, Guaidó is president; no, Maduro is president; no, Guaidó; no, Maduro; no, Guaidó” In just two hours Guaidó’s profile was edited 37 times. Now, these edit wars are frequent on Wikipedia.

[Oscar]: Every day there’s an edit war, every day there’s someone editing and someone who reverts it until one of the two ends up blocked or until they go to discussion and resolve the problem.

[Pablo]: Or until a librarian arrives to restore order. Librarians are editors with permission to block vandals and arbitrate in article wars. Let’s say they’re the ones who calm things down in the most heated discussions.

[Oscar]: The problem with that particular edit war was that it transcended Wikipedia and reached social networks, particularly Twitter.

[Pablo]: There began to appear tweets that said something like: “According to Wikipedia Guaidó is the new president.”

[Oscar]: So, what they did was retweet those who said it, with many people congratulating Wikipedia, and other people insulting Wikipedia in every possible way. And well, obviously there you see the ignorance—they thought Wikipedia is one person or an editorial group or whatever, who said “ah, Wikipedia already said it, so it must be true.”

[Pablo]: The war had left the controlled and relatively cordial environment of the discussion forum. A few hours later reports began to arrive from encyclopedia users: they couldn’t access it. Maybe it was a problem with internet connection failures, something frequent in Venezuela.

[Oscar]: But we also started receiving screenshots from people who said “no, it’s blocked. Look, I just checked it.” And they send you the screenshot.

[Pablo]: The next day they received confirmation: CanTV, the state communications agency and the largest internet provider in the country, had restricted access to the encyclopedia.

[Oscar]: I mean, it was like “wow, now what do we do?” We didn’t have any action plan or emergency plan or guide to follow. But everyone, basically, like saying “ok, now it’s our turn…” I don’t know, in a way “Wikipedia’s time has come.”

[Pablo]: Something similar could be happening to what occurred in Turkey in 2017, when Erdogan’s government blocked Wikipedia. Today there’s access there again, but in 2019 it was still restricted and that’s why Venezuelan Wikipedians were so afraid. Meanwhile, in Spain, Santiago found out what was happening. He felt disappointed but not surprised. Spending his entire childhood in Venezuela had accustomed him to it.

[Santiago]: I grew up hearing on the radio, seeing on the news about the closure of radio stations or restrictions on television…

[Pablo]: In 2019 alone, the government restricted more than 130 digital platforms. So for Santiago, Wikipedia’s blocking was the next step in strangling access to information in Venezuela. And for Oscar too.

[Oscar]: Part of losing a democratic state involves losing this access to knowledge, to you being able to read any book, to you not having a limitation on seeking information. And the importance of Wikipedia is that it was mostly neutral information, that was following sources, that had no bias and that couldn’t be bent or easily biased.

[Pablo]: The Wikipedians were sure the government was behind the blocking. And precisely because of that, making a complaint wasn’t realistic.

[Oscar]: There wasn’t a judge, a court that would tell you we’re going to have a more or less fair trial to know what’s happening.

[Pablo]: So they concluded that the only thing they could do was for Wikimedia Venezuela to issue a statement.

[Santiago]: [Reading] “Wikimedia Venezuela on the Wikipedia block, official statement…”

[Pablo]: During the following days, Oscar, Santiago and the other members of the organization drafted it. They were careful with the language and arguments…

[Oscar]: “Wikipedia is a neutral source of information and operates independently…”

[Pablo]: So that at no time would it seem they were taking a stance on the political controversy of recent days. And they also avoided making accusations.

[Santiago]: “We hope that this impossibility of accessing Wikipedia has been a technical error…

[Oscar]: Has been a technical error, since official information has not yet been provided by the state…

[Santiago]: Board of Directors Wikimedia Venezuela, Caracas, January 16, 2019…”

[Pablo]: For its part, the government denied any responsibility for the blocking. The Vice Minister of International Communication told elDiario.es, a Spanish newspaper, that the encyclopedia’s fall was due to an attack that sought to destabilize Venezuela. But he didn’t explain who was behind that supposed attack. And so, a week later, and without any explanation, the connection was restored.

[Oscar]: Just as it started, in silence, total silence, that’s how it ended. And that was the end of that part of the story. I mean, we… we never knew why it was. And like everything that happens in Venezuela, I say it’s a mini crisis in something so big, and it went to the background by the second day. Obviously not for us. But people, well, they said “ok, I can now access Wikipedia. I forgot about this.”

[Daniel]: But in October of that year, 2019, Santiago received an alert in his email. A new article has appeared. And then another. And another. And this time the attacks also mentioned Oscar and Wikipedia.

[Daniel]: We’ll be right back

[Daniel]: We’re back. Here’s Pablo.

[Pablo]: The articles Santiago saw appeared for weeks. They were written in English and Spanish, apparently by different authors. But they all repeated more or less the same story.

[Santiago]: “Santiago is the extortionist writer of Wikipedia. He has a criminal record. He’s dedicated to placing false information on Wikipedia and then extorting those affected seeking to profit from this. He lived near La Trinidad in Caracas, Venezuela. And now he lives in Spain. Partner of Oscar.

[Oscar]: It was like a bucket of cold water falling on your head or a rug being pulled from under your feet and you’re like “ok, this is another level.”

[Pablo]: The articles combined truths with lies. For example, one of them mentioned Wikipedia’s blocking—something true—and how Oscar and Santiago were responsible—something false. Some were published on platforms like YouTube, Medium, Globedia and Steemit, but others appeared on much more obscure sites, blogs that pretended to be digital media.

[Santiago]: They posed as news outlets. They published some news that was true. Like current events, right?

[Oscar]: And they also posed as us in some parts. They created, in my case, on this platform called Medium, which is like a blog. They created OscarCostero.2, and launched news from me that I was charging money to edit Wikipedia.

[Pablo]: But also, on Wikipedia’s discussion pages, in articles where Oscar and Santiago had contributed for years, messages like this one appeared.

[Santiago]: “Command, thank you for locating the leak and illegal activities of Santiago. He thinks he can hide behind users and pseudonyms without being detected by intelligence. Venezuelan agents in Spain will take the case of this extortionist.”

[Pablo]: In the midst of all this harassment, the slander and fake news, something particularly distressing for Santiago was that those comments on the encyclopedia were poisoning that space that both he and Oscar considered safe. And they had no way to respond.

[Oscar]: You, without being a public person, because you weren’t an opposition politician, you weren’t, perhaps, a director of a non-profit—sorry—human rights organization, you found yourself humiliated by this information.

[Santiago]: It’s very confusing and very frustrating because above all there’s the question of how you respond to this. All of this is anonymous, you know?

[Pablo]: It was as if they were surrounded by a smoke screen, not knowing where the next blow would come from. And amid all that confusion they had the certainty that they were being attacked for editing Wikipedia articles about Venezuelan reality. So the first thing they did was seek help from various human rights organizations in the country.

[Oscar]: And many told us “wow, this is the first time this happens with Wikipedia,” that’s what they told us, “because this is happening on this platform and on another platform with other people, other digital users.”

[Pablo]: Other Venezuelans—journalists, activists, officials, businesspeople—had also suffered similar online attacks. But, beyond this small comfort, the help from organizations was limited. One of them told them that the best they could do was try to reduce the damage on their own.

[Oscar]: So that was another process, I would also say quite solitary, of not only knowing that those articles exist, but also then chasing those articles to try to get them taken down from these different platforms.

[Pablo]: They managed to get the defamations against them deleted on some sites like Wikipedia, Medium and YouTube…

At the same time, they began to reflect on their own steps. They wanted to understand what exactly they had done to be attacked in such a deliberate and sophisticated way. So they made a chronology with each of the defamations and fake news in which they were mentioned, starting with those Santiago suffered in 2018.

Then they compared those attacks with the Wikipedia articles where they had been editors. In other words, they tried to connect the dots to see in which of their thousands of edits they might have made enemies without realizing it. And so, Santiago remembered an article he had written in 2017 and with which, according to him, everything probably started.

The article was about an attack in Caracas in the 90s. I won’t give more details to protect Santiago’s identity on Wikipedia. He created it in July 2017, shortly after being detained during the protests. And well, when he published it nothing unusual happened.

But, remembering, Santiago recalled several things that now seemed strange to him. First, in the months following publication, a couple of vandals entered the article to remove references to the man accused of the attacks, a businessman linked to Chavismo. They even changed the letters in his name.

It was obvious they were spelling it wrong, as if they didn’t want the accused man’s identity to be known. At that time Santiago did what he always did: he reverted the vandalism, so the article would reflect the correct information. It was an edit like so many others, so he didn’t give it much importance then.

Another suspicion: one of those vandals had as a username on Wikipedia the name of the man accused in the attacks. And although it was impossible to verify if it was the same person, it was strange that his only contribution to the encyclopedia had been modifying the article we’re talking about.

And well, the most suspicious clue of all: a couple of months after this small confrontation, the first attacks against Santiago began.

At that time, he had no way to connect the two incidents—his encounter with vandals on the encyclopedia and the online attacks. But now that he and Oscar had been harassed for months, the relationship seemed more likely. Especially because there was another much more recent article where something very similar had occurred.

The article was about Rafael Núñez, a Venezuelan cybersecurity expert and director of a company dedicated to cleaning people’s online reputation. Oscar and Santiago read it for the first time in early 2019. And they were struck that the article seemed promotional. Núñez appeared in a photo, smiling, dressed in a suit, like in a résumé or LinkedIn portrait.

[Santiago]: Oscar and I intervened and came, look, I mean, there’s something weird here. We see this activity that always seems to be promotional. Look, this article should reflect all points of view. It has to have this…

[Pablo]: In other words balance, contrasting sources, neutrality. The article was so biased that an edit war was already forming around it. Specifically, several users couldn’t agree on whether to leave or remove this information: that Núñez had been accused of collaborating with Nicolás Maduro’s government to fabricate evidence against a political dissident named Lorent Saleh. So Santiago entered the war. He restored the information, removed promotional content, argued with vandals and other users. And then, when the war had already been going on for months, Oscar also got into the fight. In the forum he wrote that the whitewashing of information in the article seemed to him, and I quote here, “enormous and shameless.” And then, within days, the avalanche of defamatory articles and videos and comments I mentioned before was unleashed.

We tried to contact Rafael Núñez for comment but he didn’t respond.

[Pablo]: In the months following the attacks Santiago and Oscar continued pulling threads, and although they had their suspicions about who the aggressors might be, they ultimately reached no conclusion. They were exhausted and confused by so many anonymous users, so many ghost sites. And so they tried to turn the page, although they couldn’t completely forget what happened to them. In October 2022, Oscar prepared to travel to Bogotá for a Wikipedia congress. And he went to the migration offices in downtown Caracas to renew his passport.

[Oscar]: And the guy who attends to me: “Look, what you have is a prohibition. Let me see what type of prohibition you have.” And he leaves with my passport.

[Pablo]: Oscar didn’t understand what that could mean, “a prohibition.”

[Oscar]: I say I was still in the fog, as they say in Venezuela. I mean, I wasn’t aware of what it could be.

[Pablo]: The guy returned an hour later and asked Oscar to go up to the second floor. There a woman received him.

[Oscar]: And she tells me: “Look, some people from CICPC are coming…”

[Pablo]: CICPC, the Scientific, Criminal and Criminalistic Investigations Corps. Something like the Venezuelan FBI. Oscar began to worry.

[Oscar]: In my mind I couldn’t conceive that I was involved in a criminal matter, so to speak.

[Pablo]: Soon three agents arrived, dressed in civilian clothes and armed. They put Oscar in a 4×4 truck…

[Oscar]: They didn’t tell me what for, they didn’t tell me where to.

[Pablo]: And they took him to the CICPC offices in downtown Caracas, a building of about 12 floors. They went up to the legitimization and money laundering department. They put him in an office where there were three men and one of them, the leader, showed Oscar a folder and told him: “You appear in this investigation.”

[Oscar]: And he starts asking me questions that I begin to realize, from the questions he asks me, because he starts telling me “Do you know Santiago de Viana?” So just by asking me that one question I already: “ah, okay, this has to do with the harassment, with Wikimedia, with Wikipedia.”

[Pablo]: The agent was very interested in his relationship with Santiago. He asked him what he did for a living. He also wanted to know how many bank accounts he and Wikimedia Venezuela had. Oscar tried to explain to the agents what the encyclopedia was and how it worked, like he was at an editathon and not in an interrogation room.

[Oscar]: I assumed a diplomatic, conciliatory position. And that, explaining, that look, what I did was legitimate. It had nothing to do with it.

[Pablo]: But those who were interrogating him didn’t seem to be listening.

[Oscar]: They weren’t neutral at all, but like they said “there must be something bad here, this organization must be behind something…”

[Pablo]: They told him they were investigating him, along with Santiago, for “incitement to hatred” and “legitimization and money laundering.” But they didn’t give more details. After an hour of questions the agents took Oscar to another office. They took photos of him, asked for his address, his parents’ address. And there, another official told him:

[Oscar]: “You seem like an honest kid. My recommendation is that you don’t get into trouble.” I mean, like giving me a recommendation, suggestion or warning. But he also made me understand that the system he was part of wasn’t a fair system then, if I continued, somehow, doing what I was doing, which for me wasn’t bad, but for him it might be, well, the consequences were going to be different.

[Pablo]: And so, after about four hours, the leader of the agents told Oscar he could leave.

[Oscar]: It was like, “well, Oscar, we have this thing here…”, pointing to the document they had that I didn’t even know was there. “We already know your phone number, we’re going to be communicating with you for other interviews and well, we’ll keep in touch.”

[Pablo]: And then he added:

[Oscar]: He said: “Look, because of this prohibition you can’t leave the country. So keep that in mind.”

[Pablo]: With this warning, Oscar left almost running from the building, with his pulse racing, wondering what he was going to do now. Because this was no longer about online harassment but about a government investigation against him and Santiago.

[Oscar]: And I immediately communicated with him. I told him “look, this is happening. They detained me.”

[Pablo]: He told him that he was also in the folder.

[Santiago]: I have to say that it didn’t surprise me as much as it might have been perhaps in the first years…

[Pablo]: Santiago was already accustomed to the emotional blows from so many attacks. And besides, now he feels safer in Spain.

[Santiago]: But added to that is that negative feeling I felt regarding Oscar, right? He didn’t have, for example, this guarantee. He was still in the country.

[Pablo]: And precisely because of that, during the following days Oscar began seeking help. A lawyer told him:

[Oscar]: This isn’t that you broke a traffic rule. It’s not that you attacked someone on the street and they’re giving you a fine. This is a political matter. I mean, you have to understand that. And political matters here are resolved in another way.

[Pablo]: In another way, meaning with a bribe, something Oscar wasn’t willing to do. Then, another acquaintance of his contacted a former CICPC agent. And that agent also had it clear that the investigation wasn’t for any crime.

[Oscar]: He said the same thing. He said: “This is a political matter. And I don’t get involved in this. I’ve already learned to know where to get involved and where not to get involved.”

[Pablo]: And so, a month later, Oscar left Venezuela. He crossed the border with Colombia on foot, with the help of a coyote.

Today, the smoke from the attacks has dissipated. There haven’t been new waves. Oscar lives in the United States and Santiago continues in Spain. But both still have the same doubts, the same suspicions and the same fear as before.

[Santiago]: There’s this feeling of anxiety, of uncertainty that if they attack me again… and this desire to continue investigating, to continue getting to the bottom of all this, but at the same time, you know?, I have to work, I have to study. I mean, I can’t allow this to eat me up.

[Pablo]: Today they admit they could have been much more careful with what they uploaded online. From what Santiago revealed on Reddit to all the personal information Oscar had in his Wikipedia profile.

[Oscar]: With all the information in our hands, we now say, you didn’t know we were idealistic, we were perhaps what you call naive.

[Pablo]: But the thing is they never imagined that editing on Wikipedia would bring them so many problems. And that’s why today, both are much more careful and selective with the topics they choose there. Oscar no longer gets involved in Venezuelan political articles. And Santiago…

[Santiago]: I’ll say it: I have self-censored and it’s something that strikes me a lot because I continue editing about the current situation, about human rights violations, about, well, criticisms that can be made against the government, all the rest.

[Pablo]: But there’s one specific topic that Santiago doesn’t dare to touch.

[Santiago]: Today, I avoid editing and writing about corruption, right? About plots, about topics, people who have been accused… precisely out of fear that there might be reprisals or that this wave of attacks that occurred might repeat itself.

[Pablo]: But beyond the fears and suspicions, the question is what effects this type of self-censorship can have on the encyclopedia. Regarding this Oscar has mixed opinions. On one hand, he knows that Wikimedia Venezuela is almost extinct, because there are almost no members left in the country. And many of the doors they had managed to open with public institutions have closed.

[Oscar]: If I’m honest with you, it’s perhaps in a period of hibernation, but it’s a period of hibernation I think I say imposed by the external situation so violent that has been lived in Venezuela during these years.

[Pablo]: But he also believes that, in the end, the encyclopedia’s decentralization and its collaborative editing system, that which attracted him so much at the beginning, that which made Wikipedia something so unique in history, will make it immune to censorship and self-censorship.

[Oscar]: In the end, I feel that articles are like a tree that grows in one direction or another, and you can intervene in them and edit them for a while and you detach yourself and that keeps growing.

[Pablo]: In other words, if two little ants stop editing, others will come to replace them. Assuming they want to do it. And assuming that external pressures don’t end up changing Wikipedia’s foundations.

[Santiago]: There’s the question of how that ecosystem is affected, right? of information, of plurality, when newspapers are closed or even are restricted, are pressured, right? And the same question applies to Wikipedia.

[Pablo]: That is, when the majority of editors are afraid, who will have the courage to continue building the tower?

[Daniel]: Pablo Argüelles is a journalist and lives in Madrid.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura and Luis Fernando Vargas. Bruno Scelza verified the facts. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with music by Ana Tuirán, Rémy Lozano, and Andrés.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Adriana Bernal, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Germán Montoya, Samantha Proaño, Natalia Ramírez, Lina Rincón, David Trujillo and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast from Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed in Hindenburg PRO.

If you liked this episode and want us to continue doing independent journalism about Latin America, support us through Deambulantes, our membership program. Visit radioambulante.org/donate and help us continue telling the stories of the region.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thank you for listening.