More Was Lost in The War – Translation

Share:

[Jorge Caraballo]: Hi. I’m Jorge Caraballo, Growth Editor for Radio Ambulante. We’re close to releasing our tenth season. Yes, already 10 seasons of telling the stories of Latin America. And in recent months we’ve been working hard, not just on producing new episodes, but also investing in our organization’s growth.

It’s a difficult time for the industry. Unfortunately, many media outlets are reducing their teams and a lot of stories are going to go untold. That’s why, now, despite the circumstances, we feel the responsibility to take a leap, to consolidate. We need to increase our capacity to take on more narrative projects and explore new ways to tell the stories of our region.

Now more than ever we need your help. That’s why we’re inviting you to join our membership program today: you can make a one-time donation or donate on a recurring basis. Your contribution, no matter how much it is, is going to help us continue to make Radio Ambulante and El hilo and other projects we want to present to you. To become a member, go to radionambulante.org/donar. Again that’s radioambulante.org/donar. Thank you in advance!

And now I’ll leave you with Daniel and a special episode before the new season. Bye!

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Five years ago, when they showed me the apartment where I live with my family now, the woman in charge of the building made it to the last room at the end of the hall. She went up to the window and apologized.

On the other side of the street, there was —there is— a large and incomplete construction project. That day in the summer of 2015, you could see inside that vacant lot full of holes and tunnels and mounds of dirt, the unfinished skeleton of a few half-assembled buildings.

You can see, not the details, but the dizzying ambition of the project. It was ten in the morning and hundreds of workers were moving around the enormous machines. “It’s noisy, I’m not going to lie,” the woman told me. “But someday they’ll be done.”

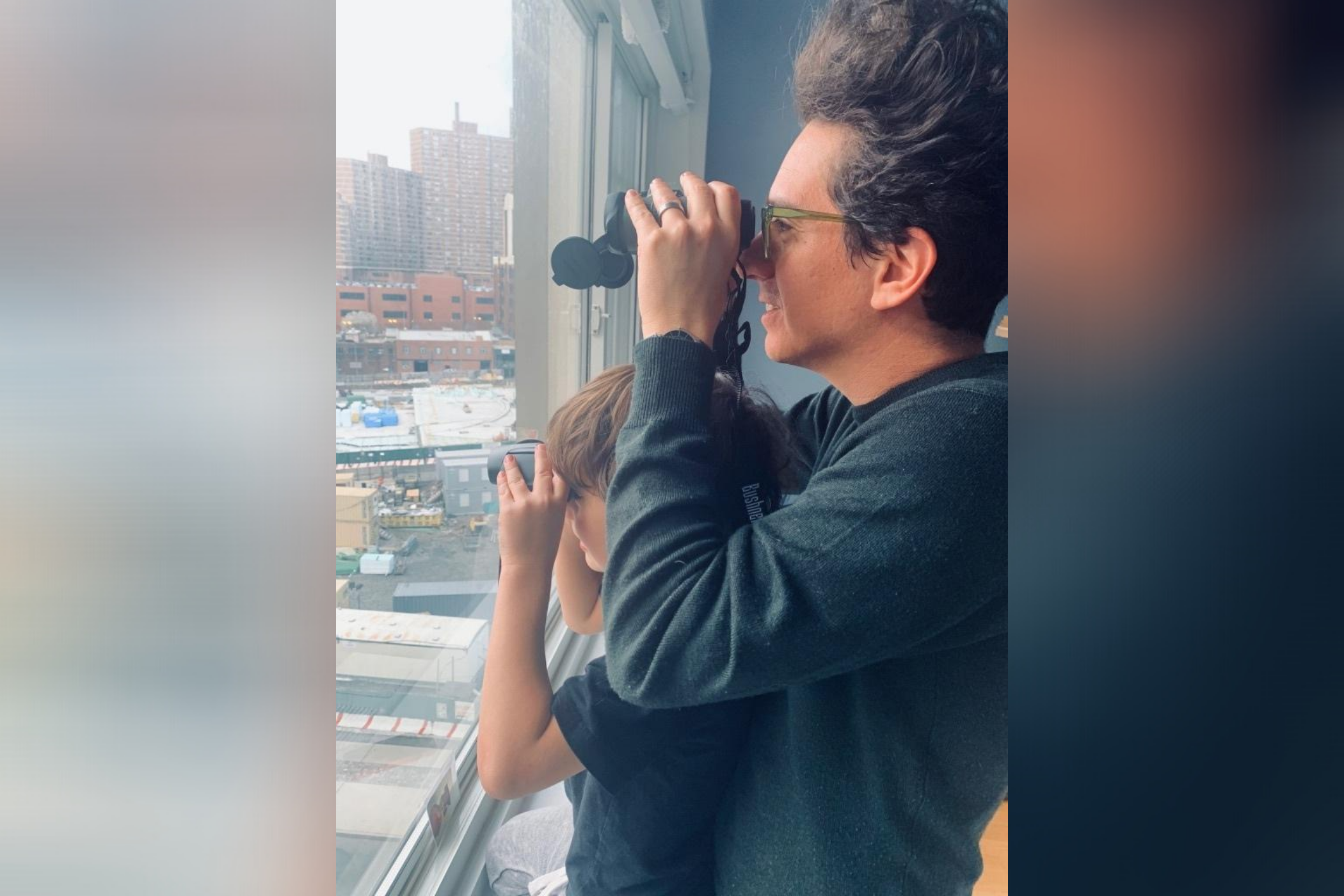

The truth is it didn’t bother me. I had left New York in 2001, and I had always wanted to go back. Now I thought about my younger son who at the time was two years old. He would be a New Yorker, I thought, one of those people who measure their years by the size of the buildings rising around them. I imagined him spending hours at the window watching the cranes, the workers moving around amid so much chaos, and I thought it would really be a privilege for him to see this cement and iron jungle, and then be able to say, as an adult, that he remembered when none of it existed. That’s what it means to belong to a place in the end: carrying its history with you always, intuitively. I always wanted to be a New Yorker; at times not being one felt like a personal failure. I thought, “My son will be, without even thinking about it.”

Now he’s seven years old and only has vague memories of living anywhere else, and he doesn’t even notice the details of the city that were so eye-catching to me when I arrived in 1995.

Like a good Manhattanite, he thinks that all cities are islands. His preferred breakfast is a bagel with lox. He talks about uptown and downtown effortlessly. He has preferences about the various bridges that connect the neighborhoods of New York to each other and to the rest of the world. When we share an elevator with a neighbor in the building, my son, attentively and politely, asks them what’s their stop —not their floor— as if he was a subway conductor.

And more than a few times I’ve found him at his window, basking in the sun and carefully watching the massive building project and its constant movement. In five years, four buildings have shot up from out of nowhere, now open to the public, and there are three more in the works. They don’t stop building. They never stop. That’s how New York is, I used to say with pride when we looked out the window in amazement at how the workers prepared for the day’s work in the rain or snow falling at full force. The cold doesn’t matter, I would tell him. The furious wind rushing up from the river doesn’t matter. Neither does the sweltering heat of summer. They don’t stop. They never stop.

We’re New Yorkers, I would tell him. We never stop.

Until March, of course. When everything stopped.

I spent my first few years here wrapped up in a kind of artificial nostalgia, tormented by the idea that the real New York existed five, ten, or twenty years before I got there. I walked a lot, eager to see every street, every neighborhood, every building, to record its details, to speak with everyone I met and collect their stories; and sometimes, I would get on the subway and go all the way to the last stop, as if I had to make sure the city actually stopped somewhere.

I have a collection of memories from those first years that I don’t dare share. Not because they’re so scandalous or compromising, in fact, it’s just the opposite. They’re ordinary: first loves and heartbreaks, small victories and failures that felt enormous. I remember readings and concerts and works of art that transformed me, but not more than my friends’ laughter, which gave me life. At 18 years old, I arrived in New York, immature, insecure, curious, with a big head of hair. A few weeks later, I shaved my head, thinking that I would look less out of place that way. My memories from those years are the same as any teenager who comes to a new, strange place and tries to invent a version of themselves that they don’t hate. Still, those banal memories stir so much emotion in me that I’m embarrassed to describe them and present them as if they were special.

Maybe the only thing special about them is their backdrop, New York. Now I realize that I arrived at a moment of transition. I first encountered the city before 9-11, when we were all less afraid, or rather we understood the world differently. Little by little, I came to understand that I hadn’t arrived late, rather just in time, that we all come to this place just in time, a city that never stops changing will always make room for the new arrival who wants to become someone else. I fell in love with this city, and it’s a love that has fixed points in time and space. Astor Place, November 17th, 1995. The West End, March 9th, 1997. Yankee Stadium, June 4th, 2001.

Before, in that innocent life in which I didn’t know what coronavirus was, I used to look out my window every morning and watch commuters walking to the subway. I would see how they were dressed so I could decide what to wear and how to dress my youngest son. Boots or no boots. Jacket or no jacket. Scarf or no scarf. I depended on my neighbors for something that basic. Now I barely see anyone out my window. I don’t know how to dress. I guess it doesn’t matter anyway. Since March I don’t have a lot of places to go.

In April, the month of the apocalypse, we got used to the sirens. More than once, during the short walks I took with my dog, I came across an ambulance parked in front of some building in the neighborhood, in time to see the EMTs going in dressed like astronauts to pick up a neighbor. In the face of a scene like that, it’s normal to wonder if the patient will make it back home someday or if they’ll die alone in a packed hospital. That’s normal to wonder. It’s also normal to cry with rage and powerlessness.

More was lost in the war.

As a child, I really liked that phrase, even though it took me years to understand it. My mom used it to brush off complaints, to minimize them. For example, if I asked her to buy me a toy all of my gringo friends had, my mom, always level-headed, would silence my complaints with a simple “more was lost in the war.” It was brutal and unquestionable, a poetic way of saying, “What are you complaining about, kid?”

It was years before I dared to ask her the question that had always bothered me: What war?

“Any of them,” she said. “All of them.”

Despite what was going on in Peru, where I was born, for me, war was something exotic, distant. I grew up in a quiet suburb of the quietest city in the Southern United States. It was all happening on the other side of the planet. It was seen on TV and we intermixed with commercials and comedies and sports. As a gringo, I knew that our wars were constant, but they were unleashed on distant countries where death and destruction were doled out among the unlucky people who happened to live in the line of fire. We, the people in the US, didn’t even take notice of what they were losing since it wasn’t our problem. No one had to teach me this. Like all national fictions, it’s something you intuited.

Now we’re used to losing things. And not just wars. Now the difficult news is taking place here. At the door of my building. In my borough, in my city. Now the local news is something we share as if we’re all living through personal versions of the same nightmare.

But I’m here to remind you that this will pass. It won’t be tomorrow, and there is a long road ahead, but this will pass.

In April, there were days when there were more than 500 deaths at the hands of this monster in New York City. Now the daily average is only 13. Which is not to say that everything is normal. Or course it isn’t. There could be a spike at any moment. But the city does feel different… There’s life in the streets. At night you can hear music coming from the park in front of my building.

Neighbors say hi to each other, at a distance, of course, and behind masks, but the custom of greeting one another that was lost in March has returned in April. Fortunately. Everything is more bearable that way. You don’t feel so alone.

It doesn’t feel like April anymore, when I woke up anxious and out of breath assuming it was COVID when really it was just fear. Not anymore. Once again, I can sit at the window with my son, watch the workers who have already gone back to work, and remind him that New York doesn’t stop. We’re not talking about a pandemic in the past tense. We know there is a lot ahead of us. But New York doesn’t stop, I tell him.

And neither do we.

A version of this essay was published in a magazine from UNAM [The National Autonomous University of Mexico] in April. This version was edited by Camila Segura. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Jorge Caraballo, Aneris Casassus, Victoria Estrada, Fernanda Guzmán, Remy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

And well, a few things before wrapping up. First, we’re hiring for several positions at Radio Ambulante, and I can say wholeheartedly that this is a great place to work. We’re ambitious in the good sense of the word, and we love to find the best storytellers and journalists from Latin America. The most creative. There’s more information on our web page.

And second, if you like what we do, please consider joining our membership program. It’s the best way to support our work. We appreciate it very much. There’s more information on radioambulante.org/donate.

That’s it. We’ll be back in September with new episodes. If you don’t know what to listen to in the meantime, I’d like to recommend another podcast from Radio Ambulante Estudios. It’s called El hilo and it comes out every Friday. Search for it wherever you get your podcasts. Both shows are produced on Hindenburg Pro.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.