My Father, My Dad | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at Lupa.app.

Translated by Lingua Viva

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. This episode contains explicit language and references to violent scenes. Discretion is advised.

The siblings Guadalupe and Tanilo Errázuriz grew up in the 90s, in a large two-story house in north Bogotá.

[Guadalupe Errázuriz]: It was like Count Duckula’s castle, as it was a huge house that was kind of gloomy but also very pretty. We had rabbits, cats, dogs, and a vegetable garden.

[Tanilo Errázuriz]: It had a really big garage where I remember I used to play football with my dad.

[Daniel]: You had a privileged, stable childhood…

[Tanilo]: I had a family circle that was always there and very solid.

[Daniel]: They lived with their mom, a very loving woman who was always concerned for their wellbeing…

And your dad…

[Guadalupe]: He was quite the hunk (laughter). Very handsome. He was a slim man with dark skin and black hair, and he wore glasses.

[Tanilo]: Slender, right? With a beard.

[Daniel]: Their mom worked at a music foundation, so their dad was the one who stayed at home with them.

[Guadalupe]: Well, he was always present, you know? As if he were our mom, ironically at that time.

[Tanilo]: It was the best. I mean, I had the best dad in the world until the age of seven because my dad was at home literally all day.

[Guadalupe]: We used to play with him all day long.

[Tanilo]: As I often remember, we would play chess on a tiny wooden chessboard.

[Guadalupe]: We used to play skittles with returnable Coca-Cola bottles…

[Tanilo]: We went to the park all the time…

[Guadalupe]: That’s how it was… he was with us all day.

[Guadalupe]: And, well, there was a lot of play, a lot of make-believe. Like, loads of imagination.

[Daniel]: He wasn’t just a good father. He did things that went beyond expectations. For example, Guadalupe remembers one Christmas well…

[Guadalupe]: We walked up to the Christmas tree and there was nothing there, and my dad was like, “Oh no, what’s going on, what could have happened to Santa Claus?” So then we went out into the garden, and in the garden there was a cherry tree. My dad had hung some bikes in the tree, along with some kind of red and white fabric that was supposedly meant to be Santa Claus, who had crashed into the tree and left everything hanging there. And it was a total surprise…

[Daniel]: Tanilo and Guadalupe didn’t fully understand what their dad’s exact job was. These and many other questions would come up later, but at that time they were really young… what they did know was that one of the rooms in the house functioned as his office. There was a desk, and a glass cabinet with pre-Columbian pieces, not a word that is said very often to children so young. They also knew that their dad would sometimes go away on a trip for a few days to seek out new pieces for an antiques gallery that his father-in-law owned. Incidentally, although the law was clear that those heritage items belonged to the state, the trade was still unregulated.

What Guadalupe remembers is that on the desk were papers, bills and…

[Guadalupe]: A stamp that was like a business card, with his name and phone number…

[Daniel]: The name that appeared there was Alejandro Arroyave. Neither Tanilo nor Guadalupe had the last name Arroyave anywhere. They only had their mother’s: Errázuriz.

[Guadalupe]: I hadn’t really ever thought about it. It had always been normal to be just Guadalupe Errázuriz.

[Tanilo]: That jumble of names, like I was an Errázuriz, my dad was an Arroyave, my cousins had the last name Pizarro and I never wondered what the hell was going on there. Well, no, these things happen. But I never gave it much importance; it was like, “I have my mom’s last name and that’s it.”

[Daniel]: Maybe, when you’re young, you don’t notice details that become important a long time into the future… especially if you feel loved and safe, with a dad who demonstrated it to you constantly. It was all pure happiness.

But in early 1995, everything changed. Tanilo was seven and Guadalupe was nearly five. They knew that their dad had driven off to look for pieces for the gallery… And they remember that a few days later their mom, María, sat down with them to tell them something.

[Guadalupe]: What I remember is that we were sitting with our backs to the window, my brother on one side and me on the other, with my mom in the middle.

[Daniel]: This is María Errázuriz, their mom:

[María]: I told them that their dad had had an accident and passed away. And no, he wasn’t going to come back.

My two little ones were stuck speechless, the poor things.

[Daniel]: What little Tanilo and Guadalupe remember of that moment is that they cried together. After that, they can hardly recall anything.

But María does have a clear recollection of the mood of the next few days.

[María]: There was a silence between us, and a kind of grayness in the house. And they would look at me, but they didn’t ask me anything.

[Daniel]: María didn’t take them to a funeral, not even a gathering with the rest of the family.

[Guadalupe]: It wasn’t a death that took on a material form, you know? It was kind of like something that you’re told about but never see, isn’t it? Even if it was just a coffin, or whatever… So for me it was never very real.

[Daniel]: It wasn’t for Tanilo either. He doesn’t remember exactly what he felt, but he does recall a reaction he had when he was eight. It was Fathers’ Day, the first one since his dad’s passing. He was at school, and all the other children’s dads arrived for the celebration. Tanilo was left on his own in the classroom.

[Tanilo]: And I remember that I lost it and trashed the classroom. I started flipping over tables… I guess I was trying to say, “Why don’t I have a dad but the others do?” I think that was when his absence hit me in a physical sort of way.

[Daniel]: In his mind he kept replaying the scene of the accident over and over again.

[Tanilo]: The car out of control in the mountains and falling off a precipice. Something like that, you know? That image really was very present in my mind, so it makes me panic. I mean, since that moment I’ve had a fear of heights and driving.

[Daniel]: What he didn’t know was that that scene never happened…

[María]: I couldn’t do it, and that’s the truth. I couldn’t tell them… I wasn’t able to.

I thought it would be less devastating for it to have been an accidental death.

[Daniel]: A car accident… because if she told them exactly how he died, she would have to tell them everything. Including the real identity of their father.

We’ll be back after this break.

[Newsletter Midroll]

[Daniel]: We’re back again on Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. This episode was produced by Ora DeKornfeld, David Trujillo, and Camila Segura.

Camila continues the story.

[Camila Segura]: María’s decision not to tell her children how their dad died meant that she had to live with that weight on her shoulders. Two fundamental things worried her.

First: having to tell them the truth.

[María]: From the moment I said what I said to them, I started to go through an anxious time of saying, “Well, the day is going to come when they have to find out what really happened.”

[Camila]: And second: finding the best way to do it.

[María]: I talked about it with my therapist… for years. What about this way, what about that way, what if I told them, what if I didn’t… I was looking for a way to… for something to draw on in order to speak about it in a way that could even be poetic. Something that would allow us to put it in a better place.

[Camila]: Until suddenly, after living with that burden for nearly ten years, the idea of how to tell them came to her when she read the book Las mujeres en la guerra (Women in War) by Patricia Lara. It features various accounts from women involved in the armed conflict in Colombia. One of them is the paternal grandmother of Tanilo and Guadalupe, Margot Leongómez de Pizarro.

I should clarify something at this point: that side of Tanilo and Guadalupe’s family has always been very political. From a very young age, four of their uncles and aunts started to get involved, in one way or another, with left-wing movements. Some time later, two of them became radicalized to the point of joining guerrilla groups.

[Tanilo]: I knew that my uncle Carlos was, well… he had been the commander of M-19.

[Camila]: Carlos Pizarro, of M-19, a guerrilla group that was active in the 1970s and 80s. He and some others formed it after deserting the FARC. Nina, his younger sister, also served among their ranks.

Guadalupe and Tanilo were aware of that part of their relatives’ lives. Carlos would go on to become a very important public figure in Colombia: in 1990, after M-19 had laid down their arms, he was a candidate for the presidency. A few months later he was killed in a situation that remains unclear, and he turned into a kind of hero, a martyr almost, for the democratic left.

The family brought up the subject very often.

[Guadalupe]: People talked about Carlos, but it was as if they were talking about the president. Because Carlos is kind of a figure to be proud of, isn’t he?

[Camila]: On the other hand, nobody talked about their dad. Virtually never. Not even after his death. In reality they barely knew anything about his life; on reflection, during that time they don’t remember seeing photos of his youth.

[Tanilo]: Why didn’t we talk about him, you know? When you’re at a family gathering, when the topics of conversation run out, you only talk about the past. But when we spoke about the past, my dad was never mentioned.

[Camila]: Well, it might have been because he didn’t get involved in politics and wasn’t as well-known as his other siblings. At the end of the day, to Guadalupe and Tanilo he was a man who sold antiques, and both of them remembered him with a personality that was more easy-going, reserved, much shier than their other uncles.

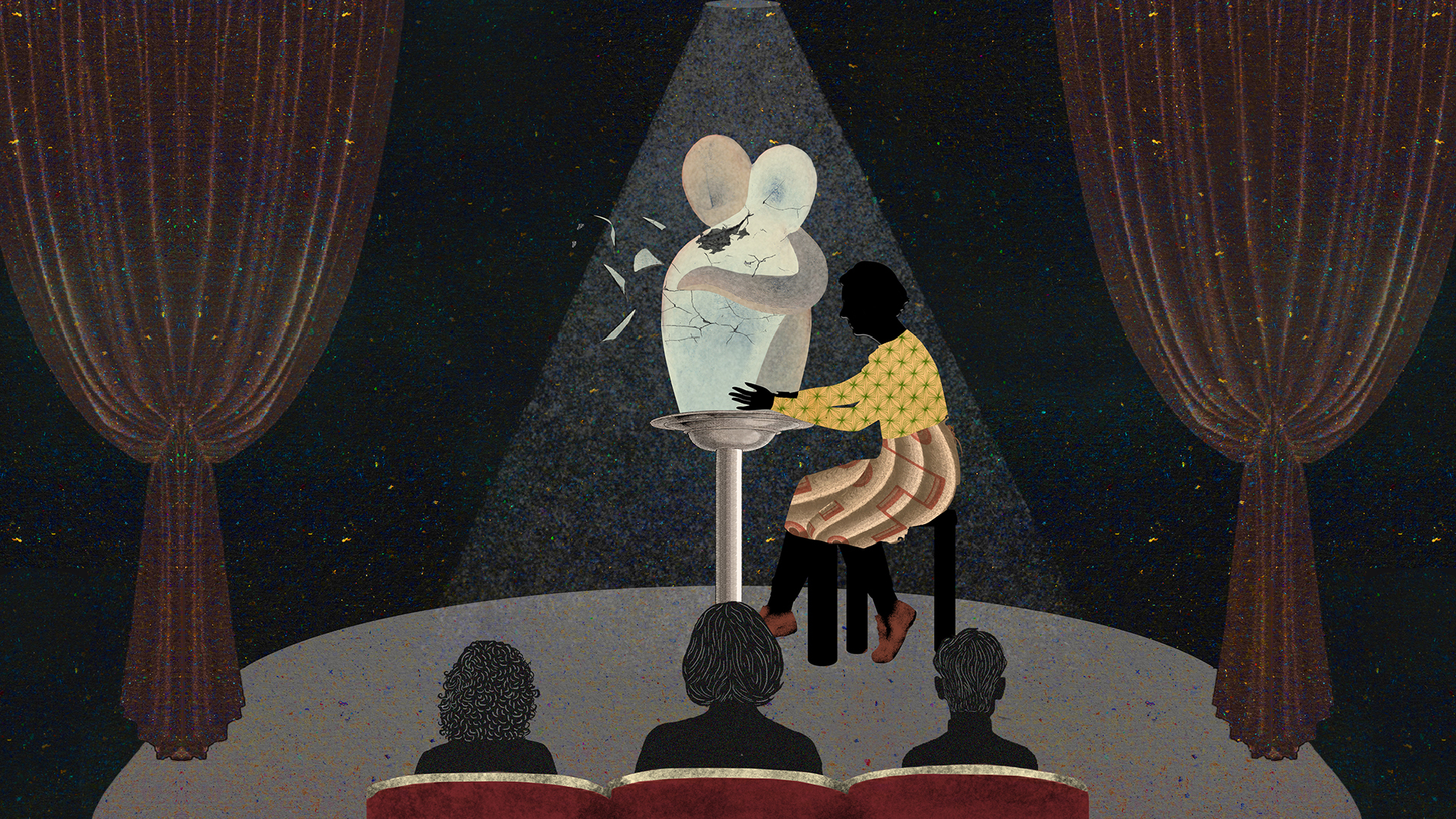

However, in the book that María had read, Tanilo and Guadalupe’s grandmother did talk about their father. She told the whole story, the story that no one had been able to tell them. When María discovered that the book had been adapted into a theater production, she felt that that was what she had been looking for.

[María]: I said “OK, I’ll go with Tanilo and Guadalupe. And there, we’ll have to say the truth about what occurred.” It wasn’t my voice that was going to talk about the loss of their father, but rather their grandmother’s voice.

[Camila]: And that’s what happened. One night in 2004, María told them she was going to take them to a stage play.

[Guadalupe]: I was 13 years old and my brother was 15.

[Camila]: They thought that it was just another of the many plays they had seen with their mom.

[Tanilo]: When I went to the theater, I didn’t have any expectations; it was like, “Oh, watching a play and the story of my grandmother, that’s kind of cool.”

[Camila]: María, by contrast, was very nervous. They went into the theater and looked for their seats.

[María]: And when we got there… I almost… I didn’t know what to do.

[Camila]: María sat between her two children, but couldn’t even dare to look at them much. This was the moment she had been avoiding for so long, and now there she was, between the two now-teenagers, on the verge of revealing many truths about that family to them. She was fearful about how they were going to react as the character representing her mother-in-law gradually gave more information. The stage curtains parted, and the play began.

[Guadalupe]: It wasn’t one of those plays with 200 characters, but only one actress talking and telling a story. I don’t know why I have the recollection that the scenography was like a stone, something very stripped back.

[Tanilo]: There were like five very different accounts from… from the war.

[Camila]: The actress, Carlota Llano, told the stories of some of the women in the first person, and when she finished each one, she changed costumes and returned to the stage to continue with the next one. Until she got to the story of Margot Leongómez, Tanilo and Guadalupe’s grandmother…

[María]: She was dressed like a lady from 1970s Cali. Draped in necklaces, with a bourgeois outfit. And she starts to tell her story.

[Carlota Llano]: My father was a colonel in the army; my husband, an admiral in the navy.

[Tanilo]: She starts talking about things. Well, yeah, like things that I more or less knew about.

[Recording from the play]: I’m the oldest of the seven children. Four women and three men.

[María]: And then there’s a moment when she says, “The war took away my son Carlos, then Hernando.”

[Camila]: Hernando… Tanilo and Guadalupe didn’t know of anyone in the family with that name.

[Tanilo]: Like, “Who’s that?”

[Guadalupe]: “But this character whose identity I don’t know, who is it?”

[Tanilo]: “Who’s that son?”

[Guadalupe]: So it was like, “What? How? Hang on, what do you mean?”

[Camila]: From then on, the things that the character representing their grandmother said began to feel confusing for Tanilo and Guadalupe.

[Tanilo]: I specifically remember when she recounted the story of the sculpture. The character said that she was making a sculpture of two people embracing.

[Carlota]: I was shaping a ceramic piece of a couple in an embrace, when suddenly the back of one of the figures burst open…

[Tanilo]: And that the statue was really hot, and when she was giving form to it, the back of one of the figures burst open. And that at that moment, one of her sons was shot in the back.

[Carlota]: They fired a bullet in his back in exactly the same spot where the figure I was making burst open… Hernando is dead.

[Camila]: Hernando is dead.

[Tanilo]: And I was left thinking… and then I stopped paying attention to the play, and all I did during what remained of it was think, “But who is that? Who’s that son?

[Camila]: They were thinking about their uncles, but they didn’t know which one of them had been shot in the back. Carlos was shot several times on an airplane, and an attempt was also made on Eduardo’s life, but he survived. Their dad hadn’t died like that either. So who was the son of their grandmother whom they had never met?

When the performance ended, María grew even more nervous. It was time to discuss what they had just seen.

[María]: Well, I sensed that everything might turn out badly, you see? That they could have felt a lot of resentment towards me: “You should have told us the truth above everything else.”

[Camila]: They left the theater and started walking.

[María]: We were all very emotional because, well, it was very, very, very impactful, and really intense.

[Guadalupe]: And then we were talking about this thing and that, and suddenly my brother was like, “Mom, but who’s Hernando?”

[Tanilo]: “But whom did they shoot in the back?” And that was when my mom bursts out crying and tells me, “Your dad.”

[María]: “But why didn’t you tell me?” And I said it was because I didn’t… I wasn’t capable of telling a boy of seven and a girl of four and a half that their dad had been killed by someone.

[Tanilo]: I got really, really mad. And it was like, “Why didn’t you tell me the truth?”

[María]: And I said to him, “Tanilo, it might be that you’re right, but I couldn’t do it. If what I did was wrong, then I ask for your forgiveness, but I just couldn’t. I couldn’t do anything else.”

[Camila]: Their mother wasn’t only telling them that their father had been murdered, but also that he had a different name to the one they knew.

[María]: Their dad, Alejandro Arroyave, was Hernando Pizarro.

[Guadalupe]: There was nothing that made more sense: on the contrary, a complete disconnect. It was like, “But my life made sense, and now what? Who’s my dad?” Right? Like that person didn’t exist.

[Daniel]: Now, all the questions they hadn’t asked for nearly ten years would come.

We’ll take a break and then come back.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: You’re back with us on Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Camila Segura continues the story.

[Camila]: After having that short but brutal conversation right on the street, Tanilo, Guadalupe and María kept walking until they reached a nearby restaurant. María felt that the most difficult part was now over.

[María]: “OK, well, from now on we’ll continue to be in mourning, but we’re in the truth,” and… I felt something like this: an incredible relief, like you can’t imagine.

[Camila]: But while they were eating, Tanilo and Guadalupe tried to begin to comprehend this new information: that apart from having another name, their dad had been killed. And from what they managed to deduce from the play, he had also been a guerrilla fighter like their uncles and aunts.

[Tanilo]: I think that was when I started to ask myself, “Well, what’s that about? Who was he?” You know? Like a seed had been sown.

[Camila]: Her children’s questions didn’t stop there. On the contrary, they would become a search to try and arrange the pieces of the jigsaw that was their family history.

[Camila]: The first piece was that María met Hernando in the city of Cali in 1970. She was about 16 and he was 18. They studied at the same school and frequented a film club.

[María]: A really good-looking guy. Very shy. He didn’t speak much. But he was a kind of calm person, you see? Sort of gentle, very reserved. He was always very reserved.

[Camila]: After that they became good friends, with no romantic relationship. In 1972, however, they were separated for 11 years: during that time María went off to France to study. Hernando stayed in Cali, and while at university he joined JUCO (the Colombian Communist Youth) along with his siblings.

María also went into more details: she told them that knew nothing of Hernando for the 11 years she was in France, but that when she came back and saw him again she found out that he had joined the FARC with his brother Carlos and had even spent time in prison. She also told them that around that time Hernando had left the FARC and founded a dissident group called the Ricardo Franco Front. María remembers well how she reacted when she found all of this out.

[María]: I said, “Oh, how terrible! What is Hernando caught up in, my God!” For me, it was very shocking to see him in that situation.

[Camila]: But María liked Hernando a lot. And she knew that it was mutual.

[María]: I don’t know whether I was crazy, or… but well, nothing. I think that we had a really strong emotional connection as children. And that carried more weight than the rationality of… I don’t know. We fell in love and decided that we would make a life together for as long as we could.

[Camila]: With all this new information that her mom was giving her, Guadalupe tried to investigate more on her own. She started searching among boxes and old papers…

[Guadalupe]: I found loads of ID cards and passports with different names.

There were a lot of photos that looked like him in disguise. He took photos of himself disguised as a woman, and then appeared later disguised as an old man. I think he must have had a paranoia about being found, don’t you think? I believe it was like a verification, because he didn’t actually use them for anything. But it was like he needed to see to what degree he could be unrecognizable, wasn’t it?

[Camila]: From time to time, María would tell them some things that seemed unbelievable.

[Tanilo]: And things started coming out, like my mom telling us that my dad kept a grenade in his pants at all times, and he used to say that if they caught him he’d blow himself up so they couldn’t capture him… that in the room I grew up in, which was like a storage room for burial chamber treasures, my dad had left like 30 kg of dynamite. And so every night it rained, my mom would come into my room, take out a small amount, defuse it in the rain and throw it down the drain. There are some really crazy stories. Like, I went through my whole childhood with 30 kg of dynamite in my room.

[Camila]: Everything that they were discovering about Hernando was since his time in the guerrilla, and continued even after he left its ranks in 1986. By then, the horror of war had convinced him to lay down his arms entirely. He was 34 years old.

[María]: At that time he told me very clearly that wasn’t going to serve in the Ricardo Franco Front any more, that his decision was to pull out. And that’s what happened.

[Camila]: But leaving war behind isn’t easy, and even less so without a peace deal involved. He still had to hide away due to his criminal history. People from all over were looking for him. And during that very tough period of the conflict, the chances of being tortured and even forcibly disappeared were high.

To María, the traumas that Hernando had been left with were obvious.

[María]: I think there were times when he wanted to die, you know? He spoke very little, very very little. As if he was ill with something and you don’t know what it is. Something like that. He wasn’t the same person that I knew as a girl.

[Camila]: It wasn’t easy to deal with that situation, but even so María decided to stay there, with him. But this had a few implications. The most obvious one was living in hiding, although for her that didn’t require significant effort.

[María]: I had lived abroad for so many years that I was a bit cut off from a lot of people too. I could live in hiding as well; I wasn’t a prominent figure in any way.

[Camila]: María continued her daily life, living alone and working at the same place, but she told almost nobody about her relationship with Hernando. Only two of her siblings and a friend knew about it.

And, well, even now María knows that many people won’t understand her decision to build a life with a man like Hernando.

[María]: But human lives are so unique and unrepeatable. What you decide at a given moment is… is determined by so many things…

[Camila]: As for Hernando, he moved to a small house on the outskirts of Bogotá. He was already well versed in hiding himself away, and he had another identity from before he left the guerrilla.

[María]: They didn’t choose that name. The opportunity simply presented itself to have the legal ID card of a person who was called Alejandro Arroyave. He had a passport, all legal. The thing is, living clandestinely has its rules.

[Camila]: But besides his new identity, to be completely safe they had to have as little contact as possible with other people.

[María]: We had a very limited social life.

[Camila]: They preferred to take trips outside the city, or go out at night to avoid running into anyone.

Over time they got used to that life, but Hernando’s paranoia never went away completely. María’s challenge also consisted of gradually breaking down that fear, and convincing him that it really was possible to have a more relaxed life.

[María]: I think that you go like… I don’t know whether that’s like anesthesia to be able to live, or that life flows better if you really are calm. I’m not sure; I don’t really have an answer.

[Camila]: And somehow, it worked.

They felt so safe that they made the decision to have a baby. Tanilo was born in January 1988, and that changed the situation significantly.

[María]: I think that was a big boost for him… and like a balm after all the pain of the war and all that.

[Camila]: Two years had already gone by since Hernando left the guerrilla, and now that they had a child they felt that the three of them could live in Bogotá. María gradually made their relationship more public, albeit cautiously. Her parents were living in Chile at the time, but they had met Hernando when he was a teenager. So when she told them about the baby, she said that the father was called Alejandro Arroyave, with few other details.

[María]: And my mom came back for Tanilo’s birth. So when I got to the house with her, I said, “Mom, this is Alejandro Arroyave.” And Hernando said two or three words to her, “It’s great that you’re here”. Something like that. And as soon as he said that, my mom looked at him like this and said, “I know you. Aren’t you Hernando?” She asked him.

[Camila]: They hugged and his answer was left implied.

[María]: And my mom never told a soul, not even her husband because she understood the risk. But my mom did know.

[Camila]: Your dad didn’t…

[María]: Incredibly. He never, never suspected anything.

[Camila]: Especially given the fact that they ended up working together with the pre-Columbian articles.

Since he joined the guerrilla group, Hernando had distanced himself quite a bit from his family. But with Tanilo’s birth they started to talk a little more, except with Carlos. The two of them had had an irreconcilable fight a few years before and they never crossed a word again. In 1990, M-19 had laid down their weapons and become a political party. And it was in April of that year when Carlos was killed.

Despite their rift, María remembers how much the death of his brother impacted Hernando.

[María]: It nearly killed him. Hernando went back to being really depressed, really downcast, completely torn apart.

[Camila]: But a few months later, Guadalupe was born. And they had to continue a normal life as far as possible, despite them carrying that past with them.

[María]: I was betting on love saving us all. I thought that with that it would be enough to survive.

[Camila]: In 1994, they moved to that big house where their best memories were made. They bought it from a retired army general who had fought against the guerrillas, but he never suspected the real identity of its new owner.

But that small world, where they felt relatively secure, was fragile. They knew it could shatter at any moment. For that reason they took certain precautions, such as deciding their children’s last name.

[María]: We discussed it and made that choice, because if I didn’t have legal guardianship over the kids because of their last name, I wouldn’t be able to get them out in any kind of emergency or uncontrollable situation.

[Camila]: And such an uncontrollable situation occurred in 1995, only a year after moving into the house. Tanilo was seven and Guadalupe was nearly five. In February, the army captured the leader of the guerrilla front that Hernando had been a member of. There was a big risk that he would be next.

[María]: He got scared, I think, and to protect us he said, “No, l have to leave.”

[Camila]: They didn’t give the children any details, only that he was going away on a work trip. María did know that he would be in the house of another former guerrilla fighter in north Bogotá. The idea was that he would stay there until the situation calmed down. Before he left, he reminded her of a promise he had made to her:

[María]: “The day I get caught, I’ll make sure I get killed, because I won’t let them disappear me. I’m not going to leave you with that anguish forever.”

[Camila]: And that’s how it happened. A few days later, they arrived at that house looking for him.

[María]: And they dragged him out of the house and killed him in the street.

[Camila]: With several shots: one of them in the back, like the character in the play said. María found out on that same Sunday. She didn’t say anything to her children for the first few days. Later, she decided that the best thing was to lie about how he’d died. After that came the paranoia…

[María]: I didn’t know what might happen if they found out that Hernando Pizarro used to live there, didn’t know whether the house was being watched, whether they were going to… they could have taken me prisoner. I eventually decided that I would keep calm, really calm, looking up at heaven and saying, “Well, let’s hope that nothing happens here….”

[Camila]: She also considered it best not to attend the funeral organized by Hernando’s family. On top of everything else, at that time she had a job that gave her a certain degree of prominence and she couldn’t risk being seen there.

In that way, the weeks, months, and years went by. All was calm. María fell in love again and got married. Tanilo and Guadalupe got on very well with her new husband from the start. They had a life of peace, until along came the play and they began to learn the truth…

[Tanilo]: I think from the day of the play I started putting two and two together. Obviously when looking back there were always clues.

[Camila]: Guadalupe remembers a game that their grandmother Margot would play with them. It was called Hunt the Thimble.

[Guadalupe]: Which was about looking for a thimble, the thing you put on your finger when sewing, and it was really difficult but at the same time really obvious too. The idea of the game is that someone puts the thimble somewhere in the house, always in plain sight, and you look for it. It was a bit like that, such as not having a second last name, having a dad that never leaves the house; everything was very weird, but it was so weird and it was all we knew so it was, well, normal.

[Camila]: It’s one thing to discover that your father was assassinated and that he had a different name to the one you knew him by, but what Guadalupe and Tanilo were about to discover was more frightening still. Both of them started to investigate Hernando’s past on their own, without mentioning the subject to each other.

[Guadalupe]: Well, it made you kind of curious, as I already had his name to search for, so it was like, “Let’s look to see what there is.”

[Tanilo]: Like, the series of questions is very clear. The first is, “Well, how did they kill him?” and then, “OK, his name isn’t Alejandro Arroyave but Hernando Pizarro,” and I started searching for Hernando Pizarro. And what I found was that Hernando Pizarro was one of the perpetrators of the massacre of Tacueyó. And after that, “What is Tacueyó?”

[Camila]: The massacre of Tacueyó occurred between November 1985 and January 1986.

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Journalist]: Let’s continue with information regarding the genocide in the Cauca department. Today, important social and political groups in the country were still looking into the killing of more than 100 people whose bodies have been exhumed from mass graves.

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Journalist]: Our special correspondents in the cold and mountainous region of Tacueyó…

[Camila]: Guadalupe and Tanilo found out separately that the Ricardo Franco Front, the one their dad helped to form, carried out a kind of purge of its ranks.

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Journalist]: Guerrilla fighters from the Ricardo Franco Front could be the perpetrators of the massacre, according to the accounts of tenant farmers in the region.

[Camila]: According to those versions of events, over the course of roughly two months the group’s high command tortured and killed hundreds of guerrilla fighters under their command, supposedly for being moles from the Colombian army and even from the CIA.

[Guadalupe]: And, well, basically those people were in a state of madness like… well, like an extreme state. Apparently they interrogated and tortured some of them, and they snitched on some other people who in turn informed on others. And in that way, it turned into this massacre of 164 people.

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Journalist]: Over a 2-km radius, the bodies of children, women and men have been buried. Next to the bodies, military clothing has been found with the initials FRF, which suggests that those killed were from the Ricardo Franco Front itself.

[Camila]: The news team that made this report traveled to Tacueyó a few days after the massacre had begun. Guadalupe found this interview, which they conducted with alias Javier Delgado, the commander of the front and a comrade of her father:

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Javier Delgado]: We executed and brought to justice 164, that’s the total so far among those detained. We haven’t executed some of them, but it was 164 in total.

[Camila]: And there could be more dead, because in the report you can see some very young men in chains, walking in a line. It seemed like they were getting them ready to be killed.

In this question, the journalist mentions Hernando:

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Journalist]: Some leaders from other guerrilla organizations say that you, Javier Delgado, and Hernando Pizarro have gone insane and killed a load of people without realizing. What do you have to say on the matter?

[Javier Delgado]: There are 164 men, all of which admitted being part of state intelligence agencies. Men from the counter-guerrilla, from the ranks of the army, from the death squads and the black brigades. From all sorts of groups, and they all sang…

[Camila]: Although Hernando appears on camera, wearing a camouflage uniform and carrying a rifle, he doesn’t make a statement.

In her investigation, Guadalupe also came across testimonies from victims:

[Guadalupe]: There’s a survivor of Tacueyó, and she basically says that my dad was kind of in a state of shock and alienation, like… that he was a person who suddenly found himself trapped in a corner and unable to move. However, there is also another account from a boy, who does say that my dad was a monster, so I don’t really know for sure.

[Camila]: The boy she’s referring to is a survivor of the massacre who was 11 years old when the Ricardo Franco Front recruited him. For weeks he was a witness to how they killed more and more people around him.

The more information they found, the more they struggled to take it all in. The horror was greater.

[Guadalupe]: Geez! They say some terrible things about my dad, about Tacueyó, don’t they? You would read that, but not really understand, you know? Like it didn’t make sense to me, because I’d lived with my dad and he was such a loving person, and then starting to find out what the deal was with that, all his hidden sides… hmmm.

[Tanilo]: The only thing that hurts me is that… man, I don’t know… that this should never happen, and that’s that. Like… yeah, I don’t know. Yeah, like there are no words, you know? I don’t know; I don’t think there are words for that.

[Camila]: Despite Tanilo and Guadalupe already having various pieces of the puzzle, they were missing an important one: understanding what their mom’s story with Hernando was like.

María was finally willing to tell them the whole truth. She said that she had started a serious relationship with him around six months before the massacre, and that thanks to a journalist friend they were able to contact each other again, communicating through letters because it was safer that way. In late 1985, she found out what had happened in Tacueyó. However, the information was so confusing and scarce that she had no idea about what had happened to Hernando.

[María]: At first, I thought that he had been killed in Tacueyó, as there was no information about anything.

[Camila]: And she went on for the next three or four months without any news of Hernando. Until eventually she received a call from him: he had left Tacueyó and proposed they meet up. María knew then that he had not been a victim of the massacre, but quite the opposite.

[María]: I couldn’t… I couldn’t understand it. I was in disbelief; I couldn’t explain it. No, I couldn’t understand it.

[Camila]: María agreed to meet him, but more with the intention of confronting him than anything else. A lot of people were dead. And if Hernando was the second in command, he must have been involved in some way. Whatever way that was, it was equally horrible. When she saw him, she got straight to the point.

[María]: And I asked him questions vehemently, saying, “What?” What the hell? What have you got to say?” I told him that there couldn’t be 100 of them. “What do you mean, 100 moles? There might be 20 or 30, I don’t know. But are you sure that what you did wasn’t a monumental mistake, and that you didn’t kill innocent people?.”

[Camila]: But Hernando didn’t react…

[María]: He was struck speechless. He couldn’t say anything, nothing at all.

Like he didn’t know what had actually happened, you see? But he was like when you’re drowning in the sea or a lake and you manage to get out, and… and what do you feel in that first instant? Nothing. You don’t know where you’re standing.

[Camila]: He seemed so defeated and in such a bad place to María that she wanted to take care of him.

[María]: I loved him so much. And he was suffering so much that I… I stayed by his side. I thought that love could save him.

[Camila]: Among a variety of conversations, María also told Tanilo and Guadalupe about a particular feeling, one that she experienced at the precise moment when she heard about Hernando’s death.

[María]: I was filled with a kind of guilt… why did I form a relationship with a man of war? Terrible, terrible.

[Camila]: They now know that it’s guilt that their mother has carried for years.

[Tanilo]: And my sister said something to her, something like, “The only thing we can tell you is thanks for being happy so that we could be happy.”

[Camila]: And yes, María tried to be happy for their sake, to look after and protect them, the same reason she decided to invent the story of Alejandro’s death.

[María]: At the age of four and seven, your mom or dad can tell you a story, but that story can be transformed in so many different ways in the mind and heart of a child that you don’t know what that can lead to.

[Camila]: This makes us think about the lies we grow up with. On one hand, there are those that fill childhood with fantasy, like the Tooth Fairy or Santa Claus coming down the chimney… or crashing into the tree in the garden.

But on the other hand, there are those lies that protect us from harder and sometimes incomprehensible truths. And maybe part of the role of being a parent is gradually piercing holes, one by one, in the bubble that our kids grow up in… until it bursts and reality comes rushing in.

When Tanilo and Guadalupe’s bubble burst, they were forced to start assimilating two very different stories:

[Tanilo]: My dad was an angel and a demon, and he was both. I have two male parents: a father, Hernando Pizarro, and a dad, Alejandro Arroyave.

[Guadalupe]: It’s like two people became dissociated, right? It was like the Hernando who had been in Tacueyó… is a psychopath, depraved, a monster, isn’t he? But later on, when you say, “Oh, but he’s my dad”… you start to question yourself, right? “Is it true that he really is a monster?” My dad wasn’t a monster. The two things don’t fit together, do they?

[Tanilo]: And over time, you kind of ask yourself things like, “Could I have that inside me? Could I be like a monster?” You know? Like me trying to understand what part of him I have in me… like in my DNA and my being. One person can be many people. Hernando and Alejandro were two different people but yet one and the same.

[Camila]: Almost two decades have gone by since they saw the play, but they are still dealing with that truth.

[Guadalupe]: In the last year there has been a really strong internal shift, because I used to be able to talk about this and not feel anything, and now I have to think about it; I have to… like there are some unanswered questions, there are some feelings that went unmentioned or were kind of denied.

[Camila]: It hasn’t been easy to live with these two stories, with these two versions of their father. And on some days, without realizing it completely, it’s easier and perhaps even necessary to move away from Hernando.

[Tanilo]: I didn’t experience the death of Hernando. I experienced the death of Alejandro. In that sense it’s as real as any other story, you know? As anything else that’s quote-unquote “true.” Like the death that saddens me is Alejandro’s death. And it will be until… until the day I die.

[Camila]: Guadalupe and Tanilo are still in the process of discovering more information about Hernando, but they have broadly accepted the idea that they have two fathers.

There are situations that make them think of one or the other: a movie with a loving father character that Tanilo saw recently reminded him of Alejandro. One week later, a song brought Hernando to mind. When spending time with their mom, sometimes they talk about one and sometimes the other.

Of course, for them it’s easier to remember Alejandro. He was the dad they really knew. But that doesn’t mean that they try to erase the figure of Hernando, or that they want to go back inside the bubble to protect themselves from the truth. As hard as that may be.

[Daniel]: A few days after Hernando was killed, the authorities arrested a young public official from the prosecutor’s office and accused him of being the person responsible for the crime. He was in jail for more than ten years, until he was finally able to prove his innocence and regain his freedom. He has always maintained that it was a judicial frame-up.

In 2020, through the Special Peace Jurisdiction created following the agreement with the FARC, an ex-commander of said guerrilla group acknowledged that they had killed Hernando Pizarro in retaliation for the massacre of Tacueyó. Some years later, they also killed alias Javier Delgado.

Nevertheless, María, Guadalupe and Tanilo still have many questions about Hernando’s death and what happened in Tacueyó.

This story was produced by Ora DeKornfeld, Camila Segura, and David Trujillo. Ora is a documentary filmmaker who lives in Mexico City. Camila is the editorial director of Radio Ambulante, and David is a senior producer. Both of them live in Bogotá. This story was edited by me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with music by Rémy Lozano and Andrés.

Special thanks to Mateo Pizarro, Ricardo Chavez-Castañeda, Aviva DeKornfeld and Carlota Llano.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Aleán, Nicolás Alonso, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, José Díaz, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Laura Rojas Aponte, Natalia Sánchez-Loayza, Barbara Sawhill, Ana Tuirán, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios and is produced and mixed using the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.