My grandparents’ wardrobe | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: Warning: this episode contains scenes of violence. Discretion is advised. It is not suitable for children.

This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Olinda Ruiz never liked her name.

[Olinda Ruiz]: I didn’t feel comfortable with my name, ever since I was a child. And sometimes I made things up and said my name was Olivia. I was hiding behind Oli and figured that, once I turned 18, I would change my name.

[Daniel]: Olinda is named in honor of her paternal grandmother. It was her father who proposed it. Her mother didn’t like it very much, but she thought it was a nice gesture, so she agreed. After all, she saw her mother-in-law as a hard-working and honest person.

But the two Olindas were not close. Not just because of the physical distance. The grandmother lived in Yatytay, a town slightly over six hours by car from Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, where Olinda lived with her parents and her two siblings. But that distance also existed because Olinda never felt completely comfortable with her grandmother.

[Olinda]: She didn’t speak; she just stared at me without blinking, to the point that I had to look down. As if it were an interrogation.

[Daniel]: Olinda’s grandmother had white skin and blue eyes. She was imposing and reserved.

[Olinda]: My grandmother was German, that is, she had German parents, so she had a very cold and distant personality.

[Daniel]: She grew up in a German community that did not have much contact with other Paraguayans. That led her to be a closed person.

One of the things that bothered Olinda the most about her grandmother was that she looked down on anyone who was different from her, and she would make comments that bothered Olinda.

[Olinda]: Very racist. I remember she told me to wear long sleeves so that my skin wouldn’t tan and become dark. Things like that. Strange.

[Daniel]: As she grew up, Olinda began to be told that she was similar to her grandmother because she was not very sociable. She preferred to isolate herself, lock herself up and play alone with her dolls, instead of being with other children.

[Olinda]: So when I wasn’t affectionate, they kept on telling me, as a negative thing, that I was like my grandmother.

[Daniel]: They saw each other only about twice a year, and their interactions almost followed a protocol. When her grandmother traveled to Asunción for some medical procedure or some other matter, she stayed in a house she had there and spent only a few minutes at Olinda’s house, which was in a neighborhood on the outskirts of the city. She would arrive in her truck, driven by a driver, and greet her and her siblings at the door.

[Olinda]: She would never come into the house. We couldn’t greet her very affectionately either, because she didn’t like kisses, so they were the kind of kisses where you barely touch cheeks… So no physical contact or anything.

[Daniel]: The grandmother brought them homemade food and chipas, small bread rolls made of cheese and cassava flour, typical of Paraguayan cuisine, which Olinda loved to eat. That is the most loving gesture she remembers from her grandmother.

Only once did Olinda visit her at her house in Yatytay. She went there with her mother, her father and her brother. They stayed three nights. Although the grandmother had a lot of money and properties, the house where she lived was rather modest and did not attract attention. It was located across from one of the four gas stations she owned.

There Olinda learned about some of her grandmother’s oddities… like her way of working and her particular schedule.

[Olinda]: She worked early every morning. She sat at her desk and did her bills, the gas station bills.

[Daniel]: Or the pets that lived with her.

[Olinda]: She had strange animals. She had a toad, she had a one-eyed white hen.

[Daniel]: Years later, Olinda would discover that her grandmother’s peculiarities, that discomfort she felt when she was with her, the same discomfort she felt sharing the same name, had a very dark background.

We’ll be back after a pause.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Journalist Cecilia Diwan, along with our producer Aneris Casassus, reported this story. This is Cecilia:

[Cecilia Diwan]: Back then, when Olinda saw her grandmother a few times a year, she didn’t see much of her father, either. He spent about two weeks a month away from Asunción, in the town where Olinda’s grandparents had gone to live as soon as they retired. And when her grandfather, Julián Ruiz Paredes, died in 1985—about three years before Olinda was born—it was her father who was left in charge of managing the family business. They paid him a rather low salary. Olinda’s mother worked as a seamstress, making custom curtains and quilts. And although they had two incomes, the money was not always enough.

[Olinda]: He was a very loving father, but very much absent, and alcoholism was an issue that we had to live with. So his working in a different city was a good thing because my mother could keep us away from that. My father was someone who didn’t contribute much. He is very strong, but he seemed to be in the way.

[Cecilia]: For Olinda, the few days a month that her father was in Asunción with them were difficult, and when her mother made the decision to separate, it was rather a relief for Olinda. She was close to finishing high school and she wanted to be a dentist. But it was an expensive college and she couldn’t afford to pay for it. Although there were public universities in Paraguay, they were subject to fees. That is to say, you had to pay for registration, for each subject taken, and for materials. Which, in the case of dentistry, were very expensive. So she decided to go for her second option: psychology.

She enrolled at the National University of Asunción. And in August 2008, while Olinda was in the second year of her degree program, something happened that was extraordinary for Paraguay.

[Archive soundbite]

[Man]: Citizen Fernando Lugo Méndez, do you swear to fulfill the office of President of the Republic with fidelity and patriotism…

[Fernando Lugo]: Yes, I swear.

[Cecilia]: For the first time in 61 years, a government that did not belong to the traditional Colorado Party came into power. Fernando Lugo, a former Catholic bishop who led a coalition of center-left forces, won the presidency with the promise to bring about real change

It was just at that moment that one of Olinda’s professors assigned her and her classmates a practical project on ethics and dictatorship. She was surprised because she had hardly heard the topic mentioned at home or at school.

[Olinda]: The curriculum of the Ministry of Education still has very few modifications from the way it was during the dictatorship. So education is designed so that the people do not question.

[Cecilia]: At school they had only one class, about 40 minutes, where they barely saw a few names and dates. She knew that the military man Alfredo Stroessner had been president of a dictatorial government between 1954 and 1989, but not much more than that. Although it did strike her that many years later, every 3rd of November, many Paraguayans still celebrated the anniversary of Stroessner’s birth by launching fireworks in the streets.

[Olinda]: Then I read on social media that people were still celebrating and that it was wrong. Until then, nothing more. In my house we don’t talk, we didn’t talk.

[Cecilia]: To do the homework, her teacher suggested she go to the Museum of Memories. Olinda didn’t know where it was, so she looked up the address on the internet.

[Olinda]: And when I get there, I realize that it is across an intersection from one of the most important shopping malls in Asunción, and that that museum has always been there, and that we all walk in front of it constantly without seeing it.

[Cecilia]: A torture center known as La Técnica operated in that very place during the Stronismo regime. She had never heard of it. At the museum she learned that Stroessner headed a repressive and genocidal government, with the participation and complicity of the Colorado Party, the army and the police. The dictatorship ended due to its betrayal by an internal faction of the government, and in the democracy, after a long process of reconstruction, the Colorados continued to govern uninterruptedly until 2008.

[Olinda]: And the guide who gives you the tour shows me piece by piece. I remember seeing all the torture devices, rusty, worn by use… it was so disgusting.

[Cecilia]: There was the so-called “pileta,” a bathtub where opponents of the regime were submerged, hand-tied, again and again in water full of urine and excrement to cause suffocation. In the same room there was a “picana,” a device to electrocute political prisoners. Also on display was a tejuruguai, a whip with lead balls at the ends that torturers used for lashing.

Olinda followed the guide very attentively and was shocked. She observed, asked questions, and took notes in her notebook: 18,772 victims of torture, 337 disappeared, 59 executed.

[Olinda]: And there was something in each room, until we came to one that had lists of names posted on the wall and the tour guide explained that that is the list of tormentors and torturers who had been identified by the survivors. It was a huge list.

[Cecilia]: They were about five pages containing the information that the Paraguayan Truth Commission had compiled after listening to, and corroborating, the testimony of the victims of the dictatorship.

[Olinda]: Either by intuition or because—I don’t know—as an exercise in searching for my last name, I look for the R and there I see Julián Ruiz Paredes.

[Cecilia]: Julián Ruiz Paredes, Olinda’s grandfather.

[Olinda]: I got chills and I think it was almost a panic attack, because before getting to that list, I had seen the entire structure of how it worked, and this was just too much.

[Cecilia]: In shock, and without a word to the museum guide, Olinda ran away.

[Olinda]: I started to feel something like shame. I mean, I didn’t even want to ask, because that was my grandfather.

[Cecilia]: Once outside, she began to cry, grabbed her cell phone, and decided to call her mother, not her father.

[Olinda]: Because my father was very fragile. I mean, my father, suffering from alcoholism, was not the person I could call and consult. I always had to be careful with him, so my mother seemed to be more—how shall I put it—trustworthy.

[Cecilia]: When her mother answered, Olinda went straight to the point, without hesitation:

[Olinda]: And I said, “Mom, I’m at the Museum of Memories and I just saw the name of my grandfather, Julián Ruiz Paredes, on the list of torturers. Is it true?”

[Cecilia]: She wanted her mother to deny it, to tell her that the information was wrong.

[Olinda]: Or for her to tell me, “Yes, but all he did was open and close the doors.” I don’t know, something smaller, because it was too much to know that he was a torturer.

[Cecilia]: But her mother confirmed what Olinda had just discovered.

[Olinda]: And she tells me, “Yes, it’s true.” And I say, “What?”

[Belinda Franco]: She asked me, “Why didn’t you tell me?” “Tell you what? I didn’t know the details.”

[Cecilia]: This is Belinda Franco, her mother. Belinda knew very little. She hadn’t shared much with her father-in-law. When she met him, he was retired, and since he lived far away, they didn’t see each other much, and he died shortly afterwards.

[Belinda]: The truth is that I got married when I was 18 years old and I came from a family that never talked about politics, never talked about anything. I don’t know; it seems like I lived in a thermos.

[Cecilia]: Belinda knew only that her father-in-law had been a police officer, but they never told her what his role had been during the dictatorship. And she didn’t ask, either.

[Belinda]: I never realized what he was, or how important he was, or what he did.

[Cecilia]: Only after his father-in-law died and democracy returned, did she begin to hear rumors in the neighborhood. Some neighbors told her that Julián had tortured people. But Belinda didn’t give them any importance; she thought it was just gossip. The fact is that in the 25 years the marriage lasted, she had never talked about it with her husband. He had told her very little about his family history and his childhood. Belinda sensed that it was a stage in her life that he preferred to forget, and she respected that.

[Belinda]: I am the kind of person who believes that ugly things must be ignored. Of course this isn’t just ugly, is it?

[Cecilia]: On the other end of the line, Olinda continued insisting to her mother.

[Olinda]: And she said, “But they are such ugly things. Why should I tell you? I don’t know much either,” she said. “But why should I poison you with things like that? They are things of the past. That is behind us.”

[Cecilia]: That’s when her mother asked Olinda not to tell anyone, especially her siblings. She specifically mentioned Olinda’s brother.

[Belinda]: When Oli begins to discover all these things, I begin to feel afraid for my son, the one called Julián.

[Cecilia]: Olinda’s younger brother was also named after a grandparent. For this reason, her mother feared that her son would reproach her for bearing the name and surname of a torturer.

[Belinda]: And I said, “My God, how is he going to take it?” And I was afraid that he would also blame me for not telling them…

[Cecilia]: Olinda accepted her mother’s request: she would keep the secret; she would not tell anyone anything about her grandfather’s past.

[Olinda]: That’s how I began to see how family silence works.

[Cecilia]: Up until that moment, her parents had told her a sweetened version of her grandparents.

She knew that her grandmother had been a police archivist and that her grandfather had held an important position in the police force. And, as we already said, when they retired, they settled in Yatytay, a town surrounded by jungle and fertile lands inhabited by only a handful of people. As a child, she had heard almost heroic stories about them. That her grandparents had contributed to the progress and development of Yatytay, that they had made arrangements for electricity and drinking water, that they had built a health center and a chapel. And also that, since he was a former police officer, her grandfather was in charge of bringing order.

[Olinda]: He was practically the one who was still in charge of the police station. And there were no thieves, because if there were thieves, he was in charge of taking them to the police station and making them pay.

[Cecilia]: They hadn’t lied to her, but they had chosen what to tell her. And as soon as she learned the other side of the story, Olinda began to question her own identity.

[Olinda]: It was a turning point because that’s when I stopped being an ordinary granddaughter and became a murderer’s granddaughter.

[Cecilia]: After that visit to the Museum, Olinda wanted to investigate her grandfather. She needed to know more. She searched on Google:

[Olinda]: “Julián Ruiz,” “Julián Ruiz Paredes.” “Julián,” “Julián Dictatorship.” All the combinations of words I could think of.

[Cecilia]: The first result she got was the testimony of a Paraguayan doctor. He had described on his Facebook timeline, in great detail, how Olinda’s grandfather had tortured him as well as others.

[Olinda]: And he called my grandfather a pretty savage torturer, and he began to tell a story where my grandfather shoots someone in the temple, in the middle of the eyes and how this doctor had witnessed that, and that was very shocking. Stories like that, one after another.

[Cecilia]: Of course, that was what left the strongest impression on her. But she was also surprised by how easy it was to find things about him.

[Olinda]: How the information is there just around the corner, testimonies that had always been just a click away on Google, and you can spend your entire life without realizing it. I mean, it wasn’t a secret, it was a silence.

[Cecilia]: She even found her grandfather mentioned as a torturer in a case of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Olinda also searched for her grandmother’s name on Google. She hadn’t seen her mentioned at the Museum, but since she had worked for the police, Olinda was curious.

[Olinda]: There is nothing about her. There is nothing about her on the internet. And the only thing I knew was my mother’s story that she did desk work and that she worked on identification, which was the whole issue of passports and IDs.

[Cecilia]: Apparently, it was a purely administrative job. So she focused on her grandfather. She continued investigating him on the internet. She reviewed court cases, profiles on social media, podcasts where her grandfather was mentioned. She discovered horrible things, but wasn’t able to share them with anyone.

Until one day she couldn’t take it anymore, and she decided to break the promise of silence that she had made to her mother. She first told everything to her older sister, Carina. Carina listened, but said she was afraid that Olinda would continue investigating. She feared retaliation, that they would be hurt. She didn’t want them to get into trouble.

[Olinda]: It’s not just my history; it’s also my siblings’ history. So what my sister told me made me stop. It stopped me for a long time.

[Cecilia]: She held back for years. So much so that, no matter how much she wanted to, she decided not to talk to her father or her grandmother Olinda.

[Olinda]: I was afraid, anxious, and felt very lonely.

[Cecilia]: Lonely because her sister didn’t want to know any details and, except for her mother, she had no one with whom to share what she was discovering about her grandfather. She didn’t want to tell her friends, either.

It took her a decade to dare tell her younger brother, the one with the same name as his grandfather. Maybe he would understand, and with his support she would feel some company. This is Julián Ruiz:

[Julián Ruiz]: I found out about my grandfather because my sister Olinda told me about it. It was quite shocking.

[Cecilia]: He listened to her, but—like his sister—he didn’t ask her many questions.

[Julián]: The truth is that here, among men, we have a habit of, let’s say, not talking much about feelings.

[Cecilia]: But some time after speaking with Olinda, Julián called her and told her that his father wanted to give him a gun that had belonged to his grandfather.

[Julián]: It was a 32-caliber Winchester in a state of conservation—really well preserved, something you could exhibit. I remember that it had a description on the handle at the bottom that said, “Semper in scopum.” It is a Latin phrase that means, “Always on target.”

[Cecilia]: Olinda’s brother had used the gun many times, because when he visited his father in Yatytay, they used to practice shooting in a field, shooting at cans. It is a highly accurate long-range rifle, very sought-after by collectors. But when Julián found out about his grandfather’s past, he rejected it, making excuses.

[Julián]: When he wanted to give it to me an advance on my inheritance, I simply told him that at the appropriate time, once he was no longer here, I could keep the gun with no problem. It seemed the most prudent way to say no to him without having to explain why.

[Cecilia]: But he told Olinda the reason.

[Olinda]: And he told me he rejected it because he doesn’t want to inherit something that had killed people.

[Cecilia]: For the first time in her search, Olinda felt accompanied.

[Olinda]: I felt that his rejection of it was a beautiful gesture, because he is also like me. We are a generation that is no longer in favor. So for me it was very symbolic that he didn’t accept that.

[Cecilia]: So the years passed—about nine since that afternoon when Olinda first discovered who her grandfather had been. Until, in 2017, Olinda took advantage of her grandmother’s trip to Asunción to pay her a visit at her house. Pretending it was no big deal, she dared ask her for the first time why she had gone with her grandfather to live in a town as far away as Yatytay, close to the border with Argentina.

[Olinda]: She says, “Because if the dictator was ever toppled, we were going to cross the river, and we had an apartment in Buenos Aires.”

[Cecilia]: Much as she wanted to, Olinda didn’t dare ask her grandmother what they had to escape from. She didn’t have the courage to question her and confront her.

[Olinda]: Now I think about it and I realize that I was part of the silence, too. In other words, this envelops you, envelops you, envelops you, and I don’t… It was a conversation about something that remained unsaid.

[Cecilia]: But in that conversation, Olinda felt that her grandmother somehow opened up. She heard her say things she had never heard from her, or from anyone in her family.

[Olinda]: She tells me that my grandfather was an evil person and that she had wanted to separate from him for years. Then he died. So she had wanted to separate, but his death relieved her.

[Cecilia]: Olinda felt compassion. She thought that maybe her grandmother had suffered a great deal living with that man.

The following year, her grandmother became ill, and in 2019 she died. She was 86 years old.

[Cecilia]: As soon as the funeral was over, her father and two of her aunts went to her grandmother’s house in Asunción. They were going to dismantle it.

[Olinda]: That very day. Because they are like that. Everything. Everything is quick, quick, quick. She’s dead now. We’re going to clean up everything today. Bye. That’s how they are.

[Cecilia]: Olinda told them that she needed to find some documents to apply for her German citizenship and asked them to let her join the group. In fact, that was just an excuse. What she wanted was to find more information about her grandfather.

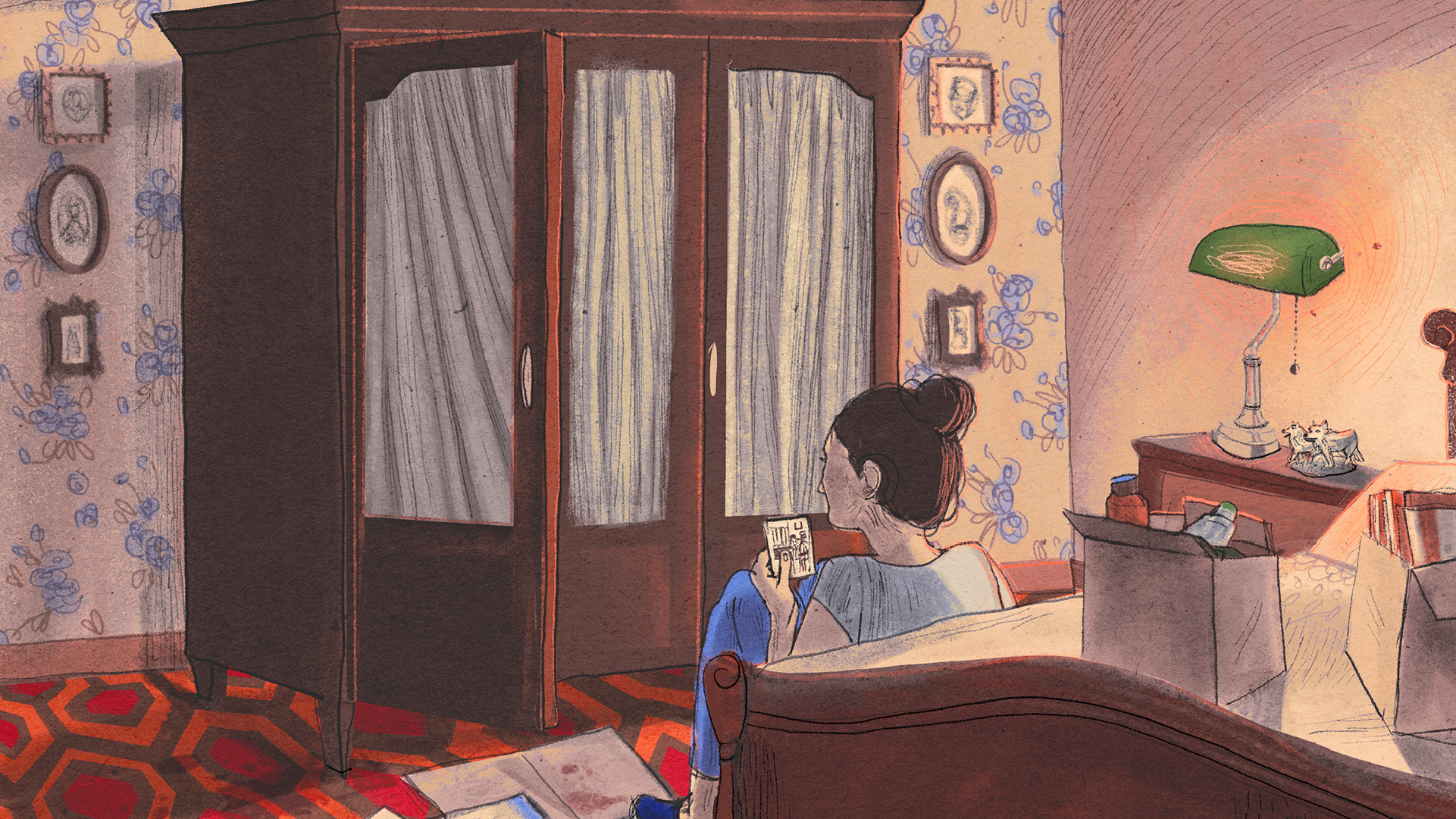

Once in the house, they began to open drawers and cupboards, laughing and sharing anecdotes. When they came to the master bedroom, Olinda immediately set her sights on her grandmother’s closet. It was made of solid wood, with two glass doors.

[Olinda]: It was a closet that was always locked, where she kept what was most private. And I had always wanted to know what was in that closet, and now I was about to open it and see what was there.

[Cecilia]: They opened it and Olinda began to look through it. In addition to sheets, towels, medical studies, jewelry and rosaries, she found her grandfather’s and grandmother’s police credentials. There was also his uniform, intact, his saber and his boots. Among some folders with documents from the national police, she discovered her grandfather’s resume, which was typewritten. She began to read it.

[Olinda]: I see, point by point, where he had been, in what year, in what position.

[Cecilia]: It was a kind of confession of some of his crimes, because it details killings in which he was involved.

[Olinda]: And the resume says: “I participated in the Agrarian Leagues operation in such-and-such year, and I was congratulated on my action.”

[Cecilia]: Here we should pause to explain what this operation consisted of. When Stroessner took power in 1954, 65% of Paraguayans lived in rural areas. That is why much of the opposition to the dictatorship took place in the countryside, and the Christian Agrarian Leagues were the protagonists of the resistance. They emerged as an attempt to form a peasant organization under the leadership of Catholic priests. Over time, they became social movements with an economic proposal based on the collective. They lived in communities, they planted together, they had their own educational plan. And they sought to carry out an agrarian reform in the eight million hectares of public land that then existed. To give you an idea, that is almost the size of Panama. But the military had other plans, and the lands ended up illegally in the hands of the dictatorship’s accomplices.

As a reaction to this, many members of the Agrarian Leagues decided to take up arms and join the guerrillas that already existed in Paraguay as the Military Political Organization, known as OPM. It was 1976, and the military repressed those rural areas to get rid of them. They tortured them, raped the women and girls, divided up all their animals and lands, and murdered them in collective massacres.

The resume that Olinda found said that her grandfather had participated in those massacres as leader of one of the brigades. Her grandfather explained how, after each operation, he rose in the ranks until he became the head of the Police Surveillance and Crime Department. And he details each time he was congratulated for his performance in an operation.

[Olinda]: He was so proud of the feats he had carried out.

[Cecilia]: Olinda became aware of what she had just discovered: data, dates and minute details that she had not found in any other document or court case. They were all there, in front of her. It was her own archive of the family terror.

While she was reading, she tried to hide her astonishment so that the others would not take the documents away from her. But her father and her aunts were busy dismantling the house and didn’t pay attention to what Olinda was looking at.

[Olinda]: Nobody wanted what I was putting together, nobody. And they didn’t ask me why I was collecting it, either. And I felt that just the fact of asking me was going to make them realize something.

[Cecilia]: Everything they found in drawers, cupboards and closets was passed from hand to hand and finally placed on the bed in the main bedroom.

[Olinda]: And it was the moment when each person had to take the things that would make a good keepsake of her.

[Cecilia]: Olinda took two plastic bags and began to put away everything that had to do with her grandparents’ police career. She was afraid that wouldn’t let her take everything, so she hid some things under her clothes.

When Olinda no longer had space, she began taking photos of everything she couldn’t take with her.

Before leaving the house, she found some photos taken at a police office, in one of the trash cans. It showed a thief, with everything he had stolen, and her grandfather behind him. It seemed like he had captured the thief.

[Olinda]: And I asked my father why he trashed it, and he said, “Because those are things that we should no longer remember.”

[Cecilia]: Her father explained that the images were part of a photo shoot for the newspaper Fortuna, in 1978. And she asked him:

[Olinda]: “May I take them?” “Yes, if you want to save them.” But there was an intention, at least on my father’s part that day, that I should not see those things.

[Cecilia]: Her father didn’t know that Olinda had been investigating her grandfather for a long time. When the four of them finished sorting and classifying things, Olinda said goodbye and went to her own home.

Months later, she began to investigate each of the documents she had found in the closet. So began a second stage in her search, and with it would come more revelations.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Cecilia Diwan continues the story.

[Cecilia]: Olinda had put the documents she found at her grandmother’s house in a suitcase. She kept it in her own closet, and for a few months she didn’t open it.

[Olinda]: They had a strange energy. They were heavily loaded. I had a whole period of insomnia, of nightmares. And it was all on my shoulders. And it was dense.

[Cecilia]: There came a time when she felt she had to understand what each piece of paper and each card was. She thought maybe that could help her get rid of the burden she felt on her shoulders. So she decided to take everything out of the suitcase and pasted the photos, documents, clippings, resume, and cards on one of the walls of her house. She even hung an x-ray of her grandfather’s chest on the rail of the lamps that illuminated the living room. She began to put things together. She was building a kind of evidence map, like the ones in detective movies.

But she was missing information that she guessed only her father knew, and that’s when Olinda finally worked up the courage to face him. It had been twelve years since she had started investigating her grandfather, and seven months since her grandmother’s death, and she had never dared talk to him about this topic.

It was March 2020, and Paraguay had just entered a period of strict quarantine due to the pandemic. So she started chatting with him on WhatsApp. She began by sending him a photo of her grandfather’s police card that she had found in the closet, and asked for context. Her father answered little by little. Olinda increasingly wanted more details. She also asked her father about testimonies she had found on the internet and in court cases that said her grandfather had been a torturer. But at first, he denied it.

[Olinda]: With great effort, he wanted to continue covering my grandfather up. He said, “Yes but those were different times,” and I said, “Yes, but grandfather killed people.” “No, he didn’t do that. Times were different. In those times you had to be strict, you had to be tough. And your grandfather was severe.”

[Cecilia]: During the first months of the exchange, Olinda reproached her father for having hidden a part of her grandfather’s story from her. But after a while, she began to work on the issue with her psychologist, a Chilean human rights specialist, with whom she met virtually. Between sessions, she realized that her father had wanted nothing more than to protect her. And she understood that she was grateful to him for having kept her out of her grandfather’s crimes during her childhood. And that’s what she told him.

[Olinda]: Because it seems that all his life he made an effort so that I wouldn’t find out. His life plan was to make sure my siblings and I never found out. So my saying thank you was touching to him; it freed him.

[Cecilia]: From then on, her father changed, he opened up and recognized that Olinda’s grandfather had been a repressor. He then began to tell her things that he had never told anyone. And it was no longer necessary for Olinda to continue asking him questions or sending photos. When he remembered something, he just sent her a message. He told her, for example, that when he was a child, his father used to take him to the Investigation Department, and that to get to the desk, he had to first go through the dungeons and the torture room.

[Olinda]: He told me, “I saw, I saw the bathtub that was used for torture. I sensed the smell of excrement. I heard the screams and I left as fast as I could and ran out of there.”

[Cecilia]: Olinda learned that her grandfather used to beat her dad savagely and that at one occasion he almost lost an eye.

[Olinda]: When he misbehaved or did something bad, the punishment was to take him to the dungeon for a few days.

[Cecilia]: When he was a teenager, he was left locked in a cell with the political prisoners. And her grandfather locked her aunts up in dungeons along with prisoners so that they could act as spies and get information.

[Olinda]: Not even Edgar Allan Poe could have imagined a story as terrifying as my grandparents’ family. They were hair-raising.

[Cecilia]: Knowing that past made Olinda see her father in a different way.

[Olinda]: It changed completely; that’s when everything made sense. In other words, that’s when I realized why my father hadn’t told the story. That was all I could ask of him.

[Cecilia]: She was able to understand why he had that personality and realize what led him into alcoholism.

[Olinda]: It was very difficult to understand why he was like that. It did not make sense. It’s only when I start putting the pieces of this together that it makes sense. He is also a kind of repairer deep inside, for us.

[Cecilia]: Olinda told her mother what she was finding out. Her mother supported and listened to her without interfering too much, although she was also shocked. This is Belinda again:

[Belinda]: And it was really very hard to realize that we were with that type of people, and that we are also part of the family, you know?

[Cecilia]: The mother felt guilty at times for not having realized her in-laws’ past. Perhaps, for not having inquired more about it, but, on the other hand, she believed that her naiveté was what kept her safe.

[Belinda]: And I was so close, wasn’t I? I was so close to them. But no, I didn’t realize it. And on the other hand, I say: It’s good that I didn’t realize it because that’s why I was able to survive.

[Cecilia]: For Belinda, it was also important to know her ex-husband’s past.

[Belinda]: And now we understand a lot of things about why our marriage didn’t work out. He had many scars that I didn’t understand.

[Cecilia]: After months and months of WhatsApp conversations with her father, Olinda felt that there were no more outstanding issues between them. She remembers a specific day when she told her psychologist:

[Olinda]: “I asked my father all the questions I wanted. All of them. He answered everything. I have no more questions to ask him.”

[Cecilia]: A few weeks later, she received a call from her brother Julián.

[Olinda]: He told me, “Dad had a heart attack and died.” It seems as if he let go, he liberated, he spoke, and he died.

[Cecilia]: Olinda was deeply affected by her father’s death, and even though he had told her many things, she still felt that she had to finish putting together her family’s puzzle. So she went to a place where she had not yet dared to go to in all these years: the National Terror Archive. There are about 300 linear meters of official documentation, including the Paraguayan dictatorship. They are very valuable documents because they demonstrate, among other things, the existence of the Condor Plan. It was a joint operation by the dictatorships that governed Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay during the seventies and eighties, and which had the support of the United States. It was this system that allowed the military of those countries to cross borders with no problem, to pursue, kidnap and murder their opponents.

In 1992, Paraguayan lawyer Martín Almada—with the help of a judge—discovered in a police station the documents that the military had accumulated about the Condor Plan. He even discovered the founding document of the regional repressive operation. Almada agreed to participate in this episode, but prolonged health problems prevented him from doing so. Here is an interview I did with him in 2013 on Radio Nacional de Argentina:

[Archive soundbite]

[Martín Almada]: The Condor Plan was firstly an exchange of information and secondly an exchange of prisoners. In any location, they assumed the right to arrest, torture and kill.

[Cecilia]: Martín Almada was one of the many victims of the Condor Plan, tortured in his country not only by Paraguayan police but also by Chilean and Argentinean soldiers.

[Martín]: And the victims were, first of all, over 50% union leaders, students, journalists, teachers. The thinking class of Latin America. More than 100 thousand victims in the region.

[Cecilia]: And there, among all the documents of the Terror Archive that Almada found, Olinda saw something she had not seen before: her grandmother’s name.

[Olinda]: Until then, I had considered my grandmother to be the poor wife of a torturer, but no.

[Cecilia]: Olinda knew that her grandmother had worked in the police identification department, and that her role was to make passports and ID cards. That’s what her family told her. But she found more:

[Olinda]: I came to the one that, in ’76, changed the Identifications Department to the Investigations Department.

[Cecilia]: The Investigations Department of the National Police operated in an old yellow, two-story building located in Asunción. It was one of the destinations where political prisoners were taken and was the dictatorship’s main torture center. Olinda knew that her grandfather had worked there. But in the Terror Archives she found that her grandmother also held a position in that building.

[Rogelio Goiburú]: Her office was next to Pastor Coronel’s office.

[Cecilia]: This is Rogelio Goiburú, director of Historical Memory and Reparation of the Paraguayan Ministry of Justice.

[Rogelio Goiburú]: And Pastor Coronel was the person most responsible for all the human rights violations. He was the top torturer and murderer of the Stronismo regime.

And his right hand, his secretary, was Oli’s grandmother.

[Cecilia]: Rogelio was part of the Truth Commission and is the son of Agustín Goiburú, a doctor who was kidnapped and disappeared in 1977.

According to what Rogelio was able to reconstruct, through testimonies he obtained from former police officers and soldiers, Olinda’s grandmother was one of Pastor Coronel’s most trusted people. In addition to assisting him as a secretary, she was also was responsible for his security inside the Investigations building.

[Rogelio]: She even tasted the food before Pastor Coronel did, just in case someone had poisoned it to kill him.

[Cecilia]: As part of her routine, her grandmother would walk around the kitchen to see that everything was in order and that no one was tampering with the food. This information gave meaning to the habits and routines that Olinda had observed in her grandmother. Like the obsession she had with cooking by herself almost all the food she ate.

[Olinda]: She had strange recipes. She made her own cheese, her own butter. And she was in her kitchen for hours. She always took a nap. Then she would wake up, stay a little longer and she would work at night, and that was very strange.

Now I understand that such was the schedule where they worked. They worked at dawn; the torture was done at dawn. I think that’s another clue… a habit she kept.

[Cecilia]: As her research progressed, Olinda discovered more details that led her to change what she thought about her grandmother.

[Olinda]: The fact that she is at a desk, not as a torturer, doesn’t negate that she is also an accomplice to the entire structure.

[Cecilia]: She was also able to learn how her grandparents joined the police. First it was her grandmother who went to work with the security forces through a distant relative of hers.

[Olinda]: My grandfather was the guard of the bus that my grandmother took to work every day; he was the one who collected the money.

[Cecilia]: Trip after trip, they fell in love, and after a while, they got married.

[Olinda]: My grandmother is the one who brings my grandfather into the police. It’s her.

[Cecilia]: Once there, the two of them inside the force, they were part of the terror.

Among the files in the closet, Olinda had found her grandfather’s pyrague card. It was his first position in the police. In Guaraní, pyrague means foot with hair. This is the name they had in Paraguay for the spies and informers who infiltrated by stealth and blended in with the people. It could be the hairdresser, the taxi driver, the garbage man, the person who sold coffee. Or the guard of a bus.

[Olinda]: My grandfather was an expert at discovering things. That was his talent.

[Cecilia]: A lot of people served as pyragues because they wanted to be in good standing with the regime in order to get some benefit or work. Here’s Rogelio again:

[Rogelio]: At that time, during those 35 years, all of Paraguay was full of pyragues.

[Cecilia]: The entire society was controlled. Anyone who was not from the Colorado Party was seen as a suspect, as an enemy.

[Rogelio]: The moment you criticized the regime, you were labeled a communist. And since Law 209 and 294 said that communists had to be arrested, they had to be eliminated, the police were the bosses and the military were the bosses of the street and your life. They could do whatever they wanted.

[Cecilia]: Over the years, Olinda’s grandfather rose in the ranks until he had a central role in the Police Investigations Department, which, as we have said, commanded repression throughout the country.

From there, he built his own network of pyragues who worked for him and, according to Olinda, led him to discover several guerrillas.

[Rogelio]: And he was a ferocious torturer. He was also the person whom Pastor Coronel sent to repress in different parts of the country. He also sent him to arrest many people, bring them and torture them there in the Investigations building.

[Cecilia]: Rogelio also verified that Olinda’s grandparents put their house and land in Yatytay at the service of the repressive apparatus of the dictatorship.

[Rogelio]: They took live people there in trucks. They locked them in a room in a house that belonged to this woman, who then took them to a probably unknown destination and killed them and buried them in those places.

[Cecilia]: According to Rogelio, there are mass graves in Yatytay, where the repressors who worked under the command of Olinda’s grandfather buried their victims.

[Rogelio]: I don’t know exactly what the coordinates are, but I know that they are in the vicinity of Yatytay.

[Cecilia]: Rogelio is engaged in tracking down mass graves as part of his investigation to search for the remains of missing people. And he told me that, so far, he has identified about 30. And he wants to start excavations in Yatytay soon, if he gets financing and support. Because, although there are public organizations in Paraguay that seek to clarify what happened during the dictatorship, political pressure always appears to prevent progress towards the truth.

The fact is that the Colorado Party, after a four-year interruption, returned to power in 2013 and continues to govern to this day. And with this, the hope of clarifying the crimes of the dictatorship was postponed again. To give you an idea, Paraguay’s last three leaders tried to justify the regime. One of them—former president Mario Abdo Benítez—is even the son of Alfredo Stroessner’s former private secretary and is always proud of his father.

Despite the obstacles and the last administrations’ lack of interest in revealing what happened during the dictatorship, Olinda was ready to break the family silence and expose her grandfather’s crimes. So she decided to go one step further—search for the victims of Julián Ruiz Paredes.

[Olinda]: I needed to have that conversation with them. It seemed to me that my position as a granddaughter could be reparative, but I didn’t know how. So I started to work on the topic of forgiveness, because I wanted to ask for their forgiveness. Deep forgiveness.

[Cecilia]: But she didn’t know how to do it or where to start.

Some time back, on the recommendation of her psychologist, Olinda had discovered Analía Kalinek, daughter of a retired commissioner of the Argentinean Federal Police who was sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. In 2017, Analía co-founded Historias Desobedientes, a collective that brings together relatives of people who committed genocides, and that soon went beyond the borders of Argentina and began to get members from Brazil, Uruguay and Chile.

Olinda had watched videos on YouTube in which Analía told her own story and recounted the emotional cost she had to pay for breaking her family loyalty.

Every interview, every video of Analía, helped Olinda build her own discourse. And although she really wanted to meet her and talk to her, she was unable to write to her for almost a year.

[Olinda]: If I wrote to her, I had to own up to being the granddaughter of a genocide perpetrator. So it was very difficult.

[Cecilia]: But one day in 2021, after thinking over the topic at length, she sent Analía a message on Facebook. She told her that she was Paraguayan, the granddaughter of police officers during the dictatorship, and that she wanted to meet with her.

A few minutes later, she received a notification. It was Analía inviting her to join a Zoom call that same day. During the hour that the talk lasted, the two formed a very special connection. This is Analía remembering what she felt in that first conversation:

[Analía Kalinek]: A lot of tenderness, a lot of tenderness and also a lot of understanding about what she was going through, because I went through the same thing.

[Cecilia]: Because many people who seek to break the silence feel guilty.

[Analía]: Families like ours, which are very conservative, ultra-Catholic, where the family comes first, where you have to honor the father, where any questioning you do is punished and reproached within the family and you also second-guess yourself, and reproach yourself and question yourself. Which forces you to make a very great psychological effort to be able to, um, get rid of all that legacy.

[Cecilia]: When she spoke with Analía, Olinda realized how important the step she was taking was. Because it wasn’t just about her story.

[Olinda]: I realized that it was very important for Paraguay. I was the first family member in an entire country that was positioning herself in that way. So that made me happy, and on the other hand I panicked.

[Cecilia]: She was afraid of having to expose herself more than necessary. But Analía told her to stay calm, that the group was there to back her up, that she had to make her way at her own pace, and that she had time to decide whether or not she wanted to become a public figure.

Analía was struck by the fact that the first person to join Historias Desobedientes in Paraguay was a granddaughter and not a son or daughter. Because the person rebelling was not a direct descendant of a perpetrator of genocide, and an entire extra generation had to pass for that to happen.

[Analía]: The level of oppression is like a closed thing. In Paraguay, I mean. And of course, they had years of dictatorship. I mean, society paid a price.

[Cecilia]: A few days later, Analía organized another Zoom meeting so the rest of the relatives of repressors from Latin America who make up the collective, about 150 people, could welcome Olinda.

And a few months later, a second Paraguayan joined. Her name is Alegría González, and she is the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of people guilty of genocide.

But they wanted to grow their number, so together they began to plan the launch of the group in their country. They contacted different organizations and on December 17, 2021, “Historias Desobedientes Paraguay” was officially inaugurated.

Analía went to accompany them, and they participated in different events. Among them, a tour of the Museum of Memories, where 13 years ago Olinda had discovered her grandfather’s past in that list of repressors posted on the wall.

Several human rights defenders were waiting for them there. Among them was Martín Almada, who, as we already said, discovered the Terror Archive and was tortured when he was arrested in 1974 by Stroessner’s police under accusations of being a communist. During his captivity, he was transferred to different torture centers. Among them, the Investigations Department.

[Olinda]: Martín Almada, who is also a survivor of the dictatorship, was tortured and was imprisoned for years. He had also been a victim of my grandfather.

[Cecilia]: For that reason, Olinda was very nervous. It was the first time she was going to stand in front of one of her grandfather’s victims. She had fantasized about the scene hundreds of times. She had thought about what words to say, how to move; she had even imagined a thousand possible reactions from the victims.

Now the time had come.

[Olinda]: I was very scared, but I was ready.

[Cecilia]: Martín greeted each one with a handshake and then invited them into a room where they sat in a circle. There he proposed they do a kind of ritual where everyone spoke.

[Archive soundbite]

[Martín Almada]: It is not the past that divides us, but the lack of justice. So we light this candle so that there is justice…

[Cecilia]: When it was her turn, Olinda identified herself as the granddaughter of Julián Ruiz Paredes. She spoke about the way silence works in Paraguay, and how important it is that the families of the people guilty of genocide also help break it.

While she spoke, she was attentive to Martín’s every gesture.

[Olinda]: He looks at me with no expression. He didn’t seem to remember. I thought, I don’t know, maybe he didn’t hear the name.

[Cecilia]: She was very nervous, but she continued talking anyway. Analía was next to her and held her hand to give her courage.

When the ceremony was over, everyone began to tour the museum rooms. Almost at the end of the tour, Martín approached Olinda.

[Olinda]: And he comes up to me with tears in his eyes and says, “Thank you. It was beautiful, it was incredible.” We gave each other a hug. And no words were needed. It felt good to be like a little light of hope for him. Because that man fought so hard…

[Cecilia]: Rogelio Goiburú was also there, and he was much moved.

[Rogelio]: It will remain in the history of our country, because it was the first time that we were together under the same roof, descendants of victims, of disappeared people, and descendants of ferocious repressors and torturers. An entire story of pain, anguish and terror and shared dreams.

[Cecilia]: Paraguay has not had a process of memory and justice like the ones that have taken place in other countries of the region. Of the 450 genocide perpetrators identified by the Truth Commission’s final report, only eight received definite sentences. Most, like Olinda’s grandparents, died without being tried.

So, for a granddaughter of a repressor to be available to the victims and recognize what happened to them is a form of reparation.

[Olinda]: Although we are not the ones who committed the murders, we are responsible for maintaining family silence, which is no less important for them continuing to live and die unpunished.

[Cecilia]: It took Olinda years to free herself from her legacy. Assuming her position came at a high cost: she distanced herself from friends, and even a boyfriend, because they questioned her search for the truth. However, she never thought of giving up. Along the way, she fell apart, but she was able to rebuild herself

For decades, she had rejected the name she inherited from her grandmother. But after all this time, something in her changed.

[Olinda]: My name is mine now. Now, in fact, I like having her name so I can give it another meaning.

[Cecilia]: A name of someone who does not hide history, but makes it visible.

[Daniel]: Olinda Ruiz splits her time between Asunción and Buenos Aires. She is working on a documentary about her story. She wants it to serve as material to disseminate in schools. Since her case was made visible, she has been contacted by more of her grandfather‘s victims. She still keeps the documents she found in her grandmother’s closet, but she plans to eventually hand them over to the Terror Archive.

Cecilia Diwan is a journalist specialized in Latin American politics. She co-produced this story with Aneris Casassus. Aneris is a producer for Radio Ambulante. They both live in Buenos Aires.

Many thanks to María Stella Cáceres, director of the Museum of Memories of Asunción, and Gerardo Halpern, Doctor in Anthropological Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires.

This story was edited by Camila Segura and me. Desirée Yépez did the fact-checking. The sound design and music are by Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Adriana Bernal, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill, Bruno Scelza, David Trujillo, Ana Tuirán, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.