The Airpirates– Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

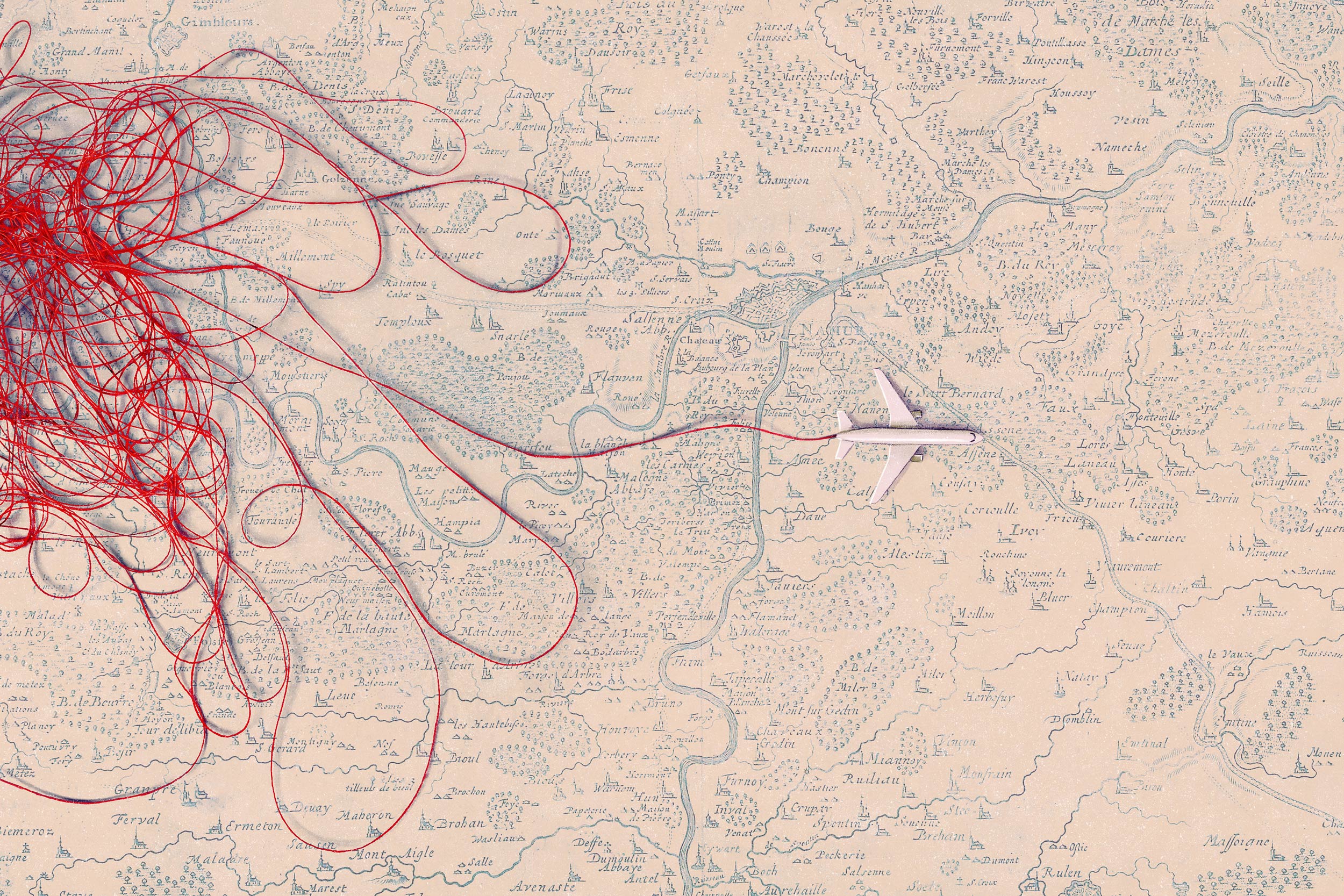

Today we’re going to travel all over the continent, aboard a Colombian plane. But it won’t be a smooth journey, I warn you . . .

We’re talking about the HK-1274 aircraft of the Sociedad Aeronáutica de Medellín, better known as SAM. It took off on Wednesday, May 30, 1973 from Bogotá and landed in . . . well . . . in many places.

The plane took off without any setbacks. The first stop was Cali.

There, cyclist Luis Alfonso Reátegui came on board. He was going to Medellín, with three other cyclists. The Clásico RCN, one of the most important races in the country, was due to start in that city the following day.

Remember that we’re in the early seventies. Getting on a plane was not the same as it is now. There were no metal detectors, no X-rays, and no one checked the luggage. It was almost like taking a bus.

This is Reátegui.

[Luis Reátegui]: Boarding was normal, using the steps. All we carried was the ticket in our hand and that got us there; we handed it over, and that was it. Almost no security . . .

[Daniel]: Today he is 76 years old and has a bicycle and motorcycle shop in Cúcuta, a Colombian city on the border with Venezuela, but at that time he was a professional cyclist who played on Valle team.

They took off at eight past one in the afternoon and at one thirty-five they made another half-hour stopover in Pereira. Once there, new passengers got on and they sat in the few seats that were free. In all, there were 84 passengers, located in two columns of seats.

Two of them sat in the next-to-last row. They were quiet, until the plane took off.

Twelve minutes later, they put on hoods. And what came next happened very quickly.

[Luis]: We were in the back. And with the two guns, they fired and shot at the . . . at the floor, and they told us to be still, it was a kidnapping.

[Daniel]: Ten thousand meters up in the air, two hooded men, 84 passengers and one shot. It took Reátegui a few seconds to realize what was going on.

[Luis]: We thought it was a joke. But when they got hold of the flight attendant, they grabbed her by the hair and talked to her harshly and everything. That scared us all very much. All of us in the plane!

[Daniel]: All the passengers kept still. There were two kidnappers, and that’s all, but they had already shown that they were not afraid to pull the trigger.

Meanwhile, no one in the cockpit had noticed anything about what was going on in the passenger section. Captain Jorge Lucena was distracted, whistling a melody. Also there were an engineer, an apprentice engineer, and the copilot, Pedro Gracia.

[Pedro Gracia]: When all of a sudden, a hooded person entered abruptly, pointing a gun at engineer Tulio Lozano and me.

[Daniel]: This is Gracia, the copilot. The captain hadn’t realized what was happening behind him. He kept whistling, while a man pointed a gun inside his cockpit.

[Pedro]: I caught his attention and said, “Captain, look.” He turned his head and went pale.

[Daniel]: A couple of minutes later, the other hijacker arrived in the cockpit. He was taller, and from the way he spoke he seemed to be in charge.

The man said, “This is a kidnapping.” And the captain replied:

[Pedro]: “Tell me what you want.” And he said just one word: “Aruba.”

[Daniel]: Thinking that he had misheard, the captain asked him:

[Pedro]: “To Cuba?” And he replied, “No, Aruba.”

[Daniel]: So began one of the most spectacular skyjackings in the history of Latin America. Producer Massimo Di Ricco researched the details of this story for years.

This is Massimo.

[Massimo Di Ricco]: That confusion on the part of Captain Lucena, thinking that the order was to go to Cuba, doesn’t come out of nowhere. Since 1967, at least thirty Colombian planes, and another 59 in the region, had been subjected to hijackings attempts with orders to fly to the island. And most had succeeded. The kidnappers used to be supporters of the Revolution, or people who wanted to leave their countries, imagining a better life there. For some, the Revolution gave rise to utopias.

Fidel Castro had come to power in 1959, and a few years later, Cuba had its relations with the continent severed, so hijacking a plane was one of the few ways to get there. There used to be little resistance from the crew, who almost always just flew to the island, hoping the matter would be over soon. Hijacking a plane in Latin America was a crazy plan, no doubt, but achievable.

The press even gave them a name: the “Air Pirates.”

For their part, the Cuban regime treated passengers well, and although they investigated air pirates to differentiate between revolutionaries, criminals or possible spies, they did not always imprison them. After all, having people willing to hijack a plane in order to live there was fine propaganda against the capitalist countries.

For Captain Lucena, it wasn’t even his first attempted hijacking. Four years earlier, a twenty-year-old air pirate had put a knife to his copilot’s neck and had given the order to go to Cuba. On that occasion, they resisted and didn’t fly to the island. Lucena even punched him. But sure, he was just a young man with a knife.

Now there were two air pirates, they had guns and they did not want to go to Cuba, but had another Caribbean island in mind: Aruba, more than a thousand kilometers from Pereira. And although that surprised the crew, they were in no position to ask questions.

[Pedro]: We were very focused. We put stress aside and began to assess the situation.

[Massimo]: This is copilot Gracia again. The first thing they realized was that they didn’t have enough fuel in the tank. Captain Lucena told the taller air pirate, the one who seemed to be the boss, that it was best to make a stop in Medellín. The man agreed.

Lucena reported from the air that they were hijacked and needed fuel. But when they touched down in Medellín, it took more than 45 minutes to refuel. And the air pirates, of course, started to get nervous.

Captain Lucena passed away in 2010, but he detailed the events of that day in an interview on Colombian television back in 1973.

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge Lucena]: He put the gun to my head for a moment: “Take off, take off. I don’t care if you don’t have fuel.”

[Massimo]: “I don’t care if you don’t have fuel.” If they did, they ran the risk of crashing in mid-flight, so the captain improvised a solution. He told the hijacker that in order to take off, they had to change runways.

It wasn’t true, but it gave him a little more time to see if the fuel would arrive. And yes, it did, but the refueling process was extremely slow. Or so it seemed inside the cockpit.

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge]: And the man got desperate again and put the gun to my head and said, “Captain, not a second more. Take off, take off, take off.”

[Massimo]: “Not a second more.” They already had enough fuel, but taking off with the tank still connected to the plane was too dangerous—it could damage the plane. Fortunately, the ground crew saw the signals from the cockpit and managed to disconnect everything.

[Jorge]: So we took off, headed for Aruba.

[Massimo]: It was already three in the afternoon. Once airborne, the hijackers seemed calmer. For the first time they said what their demands were.

[Pedro]: The request that he made known to us was first, the sum of two hundred thousand dollars in cash . . .

[Massimo]: Two hundred thousand dollars, distributed in hundreds and fifty-dollar bills. It was a lot of money. To give you an idea, at that time, with that money you could buy more than ten houses in Bogotá or at least twenty-five apartments. And there was another request:

[Pedro]: The release of their fellow political prisoners from the jail in Socorro, a department in Santander.

[Massimo]: That last sentence gave a new dimension to the hijacking. They identified themselves as members of the National Liberation Army or ELN, a guerrilla group that was about to turn a decade old in Colombia. And what they wanted was the release of dozens of comrades-in-arms who were being tried at that time, accused of belonging to the urban guerrilla.

It was an unprecedented request. Although the press always speculated that the hijackings of Colombian planes were guerrilla actions, the organizations had never admitted as much. This was the first time.

And the hijackers wanted to show that they were serious. They claimed to carry bombs in a briefcase and forced Lucena to feel them.

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge]: I put my hand in, felt some round objects, but I can’t confirm that they were really bombs.

[Massimo]: If they didn’t meet their requirements, they said, they would blow up the plane.

Meanwhile, in the passenger area, Luis Reátegui and the other cyclists were anxious. They had been separated—the women in the front of the plane and the men in the back. Their names and addresses had also been taken down.

The tall air pirate kept watch from the cockpit, and the shorter one, who also seemed the most violent, kept an eye on the passengers.

The situation was very tense. They could hardly speak without the shorter hijacker yelling and threatening them.

[Luis Reátegui]: They told us to stop making noise, not to bother them, to be quiet, that it was better for us, to keep still. And no getting up from your seat. Everyone must remain seated!

[Massimo]: People had to ask permission even to use the bathroom, and when they were allowed to go, the hijackers kept an eye outside the door, gun in hand. And although there were only two, they were still intimidating.

[Luis]: The hijackers were . . . they were stocky, muscular, but since we didn’t know who they were, they looked like El Santo, the Silver Masked Man. Yeah, that’s what they looked like.

[Massimo]: El Santo, the Silver Masked Man, the most iconic figure in Mexican wrestling. Despite the hoods, the hijackers gave the impression of being young. But most intriguing, for the cyclists, was the strange accent they had. It sounded Argentinian or Uruguayan to them, but they weren’t sure. In the cockpit, copilot Pedro Gracia had noticed the same thing, and it also seemed to him that they were trying to hide it.

[Pedro]: He spoke very little to avoid being identified, because he had a very particular accent.

[Massimo]: Two hours passed like that, until they arrived at the Princess Beatrix airport in Aruba, at five in the afternoon. It was the end of the trip, time for negotiation. But things wouldn’t be that simple.

[Pedro]: The negotiation was very difficult. The negotiator for the SAM company was an eminent lawyer named Ignacio Mustafá. He had a reputation and was known for being very, very difficult.

[Massimo]: Mustafá used to lead the company’s labor negotiation team.

[Pedro]: So, when the hijackers asked for two hundred thousand dollars, he offered just twenty thousand.

[Massimo]: It was a ridiculous offer for the hijackers. And there were other problems: They were not negotiating with the airline only, but had to deal with various governments. For one thing, they were in Aruba, and the local authorities wanted them to leave as soon as possible. As long as the plane was hijacked there, the airport could not continue operating. And, on the other hand, there were the Colombian authorities, who still hadn’t given an answer.

The news, in Colombia and Aruba, started to attract the press. As a gesture of goodwill, the hijackers let some 40 passengers off, in several batches, mostly women and children. But the others were getting desperate and some were beginning to think of plans for escape.

The cyclists, in particular, kept staring at a fire extinguisher on one of the walls of the plane.

[Luis]: There was a man who was muscular, quite stocky, strong, you know?

[Massimo]: A passenger who was sitting right in front of them.

[Luis]: So we, the cyclists, talked among ourselves. We said, “This is the man who is going to save us.”

[Massimo]: The shorter air pirate was staring at the hostages, but one of the cyclists, Carlos Montoya, dared to carefully remove the extinguisher.

[Luis]: He bent down and said, “Here’s the fire extinguisher under the . . . the seat.” And he passed it!

[Massimo]: Then he whispered the plan to the big man.

[Luis]: “When the . . . the hijacker, who always walks down this aisle, comes, you whack him with it.”

[Massimo]: The man nodded and quietly changed seats with the passenger who was next to the aisle. They were waiting for the right moment. And the moment came: The hijacker started walking towards them.

[Luis]: When the air pirate walked by, we watched to see when he would. . . whack him in the mug that extinguisher.

[Massimo]: He walked right by where they were. One nimble move, a quick blow, one of the cyclists would grab the gun, and the nightmare could be over. Reátegui looked at the man with the fire extinguisher.

[Luis]: He was . . . He had a mustache and maybe the only thing black about him was his mustache because the rest was pale. He couldn’t—white as a sheet of paper—scared, he wasn’t able to hit him.

[Massimo]: The hours passed and the plane didn’t budge from the runway. They were in the Caribbean, with the engines off, without air conditioning. The heat was beginning to be unbearable. Several passengers began to remove their clothes. They had no food or water. The bathroom was a mess and the smell would only get worse. As if that weren’t enough, while in Pereira a shipment of three hundred live chicks had been loaded into the cargo hold. It was a time bomb.

At midnight, when the hijacking had gone on for ten hours, the Colombian government issued a statement that made matters even more tense. They said they did not intend to negotiate with hijackers, and that there were no political prisoners in Colombia. Just like that, the problem of the hijacked plane was left to the SAM company. And although they were willing to negotiate a payment, the lawyer insisted that it would never be two hundred thousand dollars.

The air pirates also made a statement. They said that if the others didn’t comply, they were willing to die.

At four in the morning, the hijackers forced Captain Lucena to take off again, without telling him where they were going. Once in the air, the chief hijacker told him: They would go to Lima, Peru. It was more than four hours of flight from Aruba, and Captain Lucena began to worry about the plane.

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge]: I told the hijacker that the plane’s oil was already very depleted and the turbines could melt.

[Massimo]: This is Captain Lucena again, in the 1973 interview. The problem was that if they were going to make such long trips, they needed oil for the turbines and propellers, or they could break in mid-flight. Then, he found out by radio that they had some in Guayaquil, which was on the way. But, nearby, only Aruba had oil.

He told the hijacker that it was too dangerous to go on like this. According to Lucena, the pirate replied:

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge]: “Captain, I don’t want to risk the lives of the passengers. I don’t want to risk the life of the crew; I don’t want to risk the plane. If you think it’s best, go back to Aruba.”

[Massimo]: And so, they did. They arrived in Aruba, for the second time, on Thursday at 8:30 in the morning. Almost twenty hours of hijacking had already passed.

[Luis]: By then, I was very tired, feeling really bad.

[Massimo]: This is Luis Reátegui again.

[Luis]: Since we couldn’t talk, we would whisper by bits, figuring out what would happen, man.

[Massimo]: In Medellín, the Clásico RCN was about to begin, and, although he was not going to make it, he felt it was time to do something. But he didn’t know what.

[Luis]: But we couldn’t get up from seats, go talk to the hijackers, because they could shoot us.

[Massimo]: But he took a chance. He stood up and walked over to the shorter air pirate, the same one they had planned to knock out with the fire extinguisher. He pulled out his cyclist ID:

[Luis]: I told him, “We’re cyclists, there are four of us who are going to take part in the Clásico RCN.”

[Massimo]: The hijacker looked at him for a moment. He didn’t even examine the ID. Reátegui remembers that he said to him:

[Luis]: “I know you.”

[Massimo]: Reátegui didn’t understand. It wasn’t like he was a famous cyclist. Besides, he didn’t recognize the hijacker’s voice either. But everything happened so fast that he didn’t have time to ask him anything. Immediately, the air pirate added:

[Luis]: “Hang on, hand on, we’ll solve the problem later.”

[Massimo]: Reátegui returned to where his companions were and told them:

[Luis]: That man told me that he was going to let us go, that they were going to let us, the cyclists, go, and that we should be calm. So, well, we calmed down a little bit.

[Massimo]: A few minutes later . . .

[Luis]: They came and said—they were going like this at us with the gun— they said, “The cyclists, out, get out!”

[Massimo]: They didn’t understand what was happening but they didn’t ask.

[Luis]: We stood up, happy . . . happy with the suitcases. And we were free to go. We were so happy. We could breathe clean air, because the plane smelled—it smelled like a thousand things, you know?

[Massimo]: It was ten in the morning, and suddenly the four cyclists, along with a handful of other passengers, had regained their freedom.

It’s difficult to know exactly how many passengers were left on the plane by then. The newspapers at that time gave figures that didn’t match, but it is realistic to think that there were over thirty people left. Aside from the crew, seven of them.

The unease inside the cabin of the plane continued to grow. The hijackers announced that for every half hour that passed, they would raise the ransom by fifty thousand dollars. But the airline was still refusing to pay.

The head air pirate, pretty frustrated by then, demanded that all the local newspapers be delivered to him on the next plane arriving from Colombia, to find out what they said about the hijacking. But Captain Lucena didn’t follow that order. He may have been thinking of the danger if he read something in the news that he didn’t like.

When the first Colombian plane arrived and they were told from the tower that it had not brought any newspapers, the hijacker exploded.

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge]: He said, “Captain, you’re lying to me.” He had a nervous breakdown at that point. He came back and put the gun to my head, and said, “I won’t take any more lies from you.”

un[Massimo]: The situation had reached a limit. On another Colombian flight, the airline’s secretary general, together with attorney Mustafá had arrived in Aruba. They wanted to get on the plane to negotiate with the hijackers.

(SOUND BITE OF INTERVIEW)

[Jorge]: He said to me, “Don’t let any of them come near, because, Captain, I will kill them, because I will kill them.”

[Massimo]: Nobody got on the plane. They only let a flight attendant come down to collect sandwiches and water for the passengers, who couldn’t take it any longer. Then, they ordered the captain to take off again. This time there was no specific destination. They told him to head for Central America.

While all this was happening, other passengers organized an escape plan. When the plane started to move, someone opened the rear emergency door. . .

[Pedro]: Several men began to jump to the ground.

[Massimo]: The fall was at least five meters, and a couple of passengers ended up with head and leg injuries, but none was seriously hurt.

Among those who jumped was a couple of special importance to the air pirates, millionaires and owners of one of the largest oil factories in Colombia. When they realized they had jumped, they became even more upset. And on top of that, they had an open door.

[Pedro]: The hijackers were scared and thought the opposite had happened, they thought the police had entered the plane. They were so stressed that they gave the order to take off immediately.

[Daniel]: The plane took off, amid the chaos. They flew over Panama, Costa Rica, all the way to El Salvador, but they were not allowed to land at any airport.

So, they returned, for the third time, to Aruba. They were basically where they had started. Actually, they were worse off: The Colombian government had refused to negotiate, had not given them a penny, and they had fewer and fewer hostages.

At ten o’clock on Thursday night, 32 hours after the hijacking began, the air pirates set a final deadline: eleven o’clock the next morning.

If they didn’t receive the money by then, there would be consequences.

A pause and we will return.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, we told you how two hooded men hijacked a plane in Pereira, Colombia, with 84 passengers aboard. They identified themselves as guerrillas of the National Liberation Army, and demanded two hundred thousand dollars and the release of political prisoners. But it had already been more than a whole day, and the plane had done nothing but circle around and return again and again to Aruba.

They had let out passengers, others had escaped and the authorities didn’t seem at all willing to comply with their demands.

But the hijackers were not giving up. If at eleven in the morning they didn’t have an answer, they would consider that the negotiation had ended.

And they had already said they were willing not to leave the plane alive.

Massimo takes up the story.

[Massimo]: After the third landing, Aruban authorities made a demand of the pirates—a change of crew. It was very dangerous to continue taking off with an exhausted captain and crew. In exchange, the airline would send a briefcase with fifty thousand dollars, in the hands of the new captain who would come up. The hijackers accepted.

But they had a new challenge—convincing another crew to get on a hijacked plane, one where things were getting out of control.

[Edilma Pérez]: I got there and said, “Here I am, what do you need me for? And the manager said, “We have to relieve the crew that’s in Aruba.”

[Massimo]: This is Edilma Pérez, a SAM flight attendant at the time, who was starting her shift at the Medellín airport. She was 32 years old and had just completed two years of working at the company.

It was already decided that commanders Hugo Molina and Pedro Ramírez would be part of the replacement team, as captain and copilot. And the flight engineer, Alfredo Shaffer, would also get on board. Only the flight attendants were lacking. Edilma asked which of her colleagues had already offered to go up.

[Edilma]: “I don’t know,” the manager said, “I don’t know who is willing.” So, I told him, “I’ll do it.” And he looked at me and said, “Are you up to it? Do you know what you are getting into? “Yes . . . I’ll do it.”

[Massimo]: She was a single mother of five children, and that job had allowed her to raise them. She was very grateful to SAM for choosing her. At that time, it was very rare for an airline to hire a woman with children. And in addition, she was part of the airport reserve team, which had to be there in case of any emergency or replacements.

Edilma told them one more thing: If they called María Eugenia Gallo, who was arriving on a flight from Cúcuta, she would also accept. They were very good friends and always tried to fly together.

In fact, María Eugenia had already seen the hijacked plane in Medellín, at the first stop they made to refuel.

[María Gallo]: And we saw it, we saw it at a distance, and I said to my coworkers, “Oh, how cool to be on that plane, and have that experience, and have something to tell our children, our grandchildren, later.” My companions, said “Oh, you’re crazy.” And I told them, “I don’t think so; it would be great.”

[Massimo]: María Eugenia was 23 years old, she had no partner or children, and she had an adventurous spirit. So, when she was called, she didn’t have to think twice.

[María]: I said, “Sure, I’m ready, I’ll do it. At once.” And so . . . that’s how the adventure began.

[Massimo]: María Eugenia went home to pack clothes and told her mother what she was about to do.

[María]: “Darling, you’re crazy. How can you even consider it? “My sisters too. And I said, “Oh, no, I want to, I want to go.” And I left.

[Massimo]: Edilma only told a sister.

[Edilma]: And I said, “Sister, I’m going to the kidnapping; stay with my children.” And she said to me, “What?” I didn’t give her time to respond, I just said, “My children are there. Take care of them.” And I hung up the phone.

[Massimo]: The two were ready. Their next flight together as flight attendants would be aboard a hijacked plane. A third flight attendant joined, and the entire crew arrived in Aruba at dawn. They went to a hotel to rest and eat, but when they were about to start, they received a call. They had to go to the airport immediately.

When they got there, they saw the plane in the middle of the runway.

[Edilma]: We were in a straight line. And next to the plane there was no one, no one, no one.

[Massimo]: No police, no company people, no journalists. The hijackers had ordered that no one come near, other than the crew.

The first to be released was copilot Pedro Gracia, in exchange for the new captain, who carried the briefcase with the fifty thousand dollars.

The exchanges continued, one by one, and in the end the air pirates released a group of nine more passengers. Edilma and María Eugenia were the last to go up, and they managed to see the flight attendants of the previous crew. They looked exhausted, and when they passed by, they hugged them and cried.

Edilma walked toward the steps of the plane and, once there, she began to feel the weight of the decision she had made.

[Edilma]: My legs were shaking. When I climbed the steps, I was afraid, obviously.

[Massimo]: Edilma went in and María Eugenia followed her. The air pirates checked them and told them they had to obey each of their orders, because they were in charge inside the plane.

[Edilma]: And when we got in, the plane was very messy . . .

[María]: All the chairs turned topsy turvy . . .

[Edilma]: There was a lot of trash on the plane, because they hadn’t given permission to take it off the plane yet . . .

[María]: And the chicks, how sad, they died there in the—in the belly of the plane. The smell in the plane was terrible, plus the heat.

[Massimo]: What shocked them the most was seeing the passengers.

[Edilma]: They had panic on their faces, as if saying, what are you doing here?

[María]: They looked at us astonished and we reassured them that everything was going to be fine, telling them they shouldn’t worry.

[Massimo]: But, of course, they had no way of knowing if things were going to turn out well. At least the hijackers had part of the money and they were no longer talking about releasing political prisoners. They had been hijacked for 38 hours. It was twenty past four in the morning on Friday, June 1, and the new order was to take off again—this time, toward the south of the continent.

They stopped in Guayaquil, Ecuador, and demanded fuel, food, and newspapers. This time, the new captain, Hugo Molina, did comply with the order, and the pirates confirmed that they were already famous—The hijacking was news everywhere.

Fifty minutes later, they took off again, and in midair they told the captain what the new destination was: Antofagasta, in northern Chile.

[Edilma]: The captain told him that the plane couldn’t land in Antofagasta because the plane was too big for that runway.

[Massimo]: The hijackers asked the captain for the plane’s specifications, to compare with their navigation charts.

[Edilma]: Then they realized the captain was telling them the truth.

[Massimo]: So, they changed their plan and told Molina to head for Lima. They seemed to be were improvising.

And they became more violent as the time passed.

[Edilma]: They were aggressive, yelling. Trying to appear in command. But actually, they were very nervous. They threatened us several times, pointing the gun to our heads.

[Massimo]: The air pirates had not slept for two days, taking turns to eat, use the bathroom, and keeping an eye on the cockpit or the passengers. They seemed about to explode.

But the flight attendants, who were rested, understood how to act.

[Edilma]: We chatted with them, we teased them so that they would cool down, because they were very stressed. So they began to trust us. Because if we had gotten worked up again, there would have been a shooting and we would have all died.

[Massimo]: At 10:47 in the morning, they landed in Lima. The air pirates allowed the flight attendants to clean the plane, unload the trash in bags, and collect more sandwiches and drinks. Surprisingly, they also decided to release fourteen of the twenty-three remaining passengers.

This is one of the passengers who were released, Jaime Londoño, interviewed a few hours later on Colombian television.

(SOUND BITE FROM ARCHIVE, INTERVIEW)

[Interviewer]: Sir, kindly tell us what the hijackers’ motives were for letting you get off in the city of Lima.

[Jaime Londoño]: They promised us that after Guayaquil, in Lima, they would release us without any problem, as long as the authorities didn’t act.

[Interviewer]: Why didn’t they release the other nine passengers?

[Jaime]: Because when we got to Guayaquil, they got the newspapers and the newspapers said that the hijackers had treated the personnel on board very badly, and that´s a lie. So, it seems that they were offended by that.

[Interviewer]: Tell us, have any of the hostages manage to rest at some point?

[Jaime]: No, they have not rested. They’re drugged or high.

[Interviewer]: Thank you very much for your statements.

[Massimo]: After noon, they took off again, now towards Mendoza, Argentina. At this point, it was no longer very clear what the air pirates were up to—whether they had any plans or were just flying from one place to another.

In Mendoza, in fact, they didn’t even turn off the turbines during the two hours they were on the runway. With the plane moving and turning, they lowered the steps and ordered the nine remaining passengers on board to jump off.

The control tower didn’t even notice that passengers were descending.

[María]: And the turbines were very dangerous and a great risk for the people.

[Edilma]: We just told them to run away from the propeller, because if they ran toward the propeller, the propeller would destroy them.

[Massimo]: At nine-thirty that night, and after fifty-five hours, the SAM plane took off without passengers for the first time. The captain managed to say one last thing to the control tower before leaving: They were heading towards Buenos Aires.

That’s when the communications were cut off.

The hijacking had taken a very strange turn. There were no hostages, money was no longer discussed, and the identity of the hijackers was a growing mystery. They claimed to be members of the National Liberation Army, but the freed passengers kept talking about their strange accent. At least, they didn’t sound Colombian.

Their closeness to the cyclists was also striking. And when Captain Lucena got off the plane, he said he had talked a lot about sports with the chief hijacker.

They had even made predictions for the fight between the Colombian “Rocky” Valdés and the American Leon “The Whip” Washington, who were wrestling in Bogotá.

Gonzalo Valencia was a sports journalist in Pereira, the city where the hijacking began. And he had been following the news for days.

[Gonzalo Valencia]: What was said was that they were probably people who had to do with sports, because, they had treated the cyclists who were inside the plane with a certain familiarity.

[Massimo]: There was also much speculation about their preparation. On the one hand, they carried navigation charts, they knew how to read them, they had a strict protocol to deal with both the hostages and the crew. But on the other hand, they kept flying with an almost empty plane and no clear destination.

They had fifty thousand dollars, but they would be arrested as soon as they set foot on land.

At this point in the story, the plane’s whereabouts becomes fuzzy.

Before cutting off communications, the captain had said that they were going to Buenos Aires, but the plane didn’t arrive. That night, there were some media reports that they landed in Resistencia, a city next to the Paraná River, on the border with Paraguay. And there they asked the control tower for oil, but they took off about five minutes later, without waiting for it to arrive.

After midnight, the Paraguayan media reported that the plane had requested a runway at the airport in Asunción, the country’s capital. Before landing, the captain asked the tower to turn off the runway lights. They stayed there less than ten minutes and took off again, to get lost in the night.

Shortly after three in the morning, journalists crowded into the Ezeiza Airport in Buenos Aires. This time, the plane had arrived.

Journalist Gonzalo Valencia, in Pereira, was glued to the transmission.

[Gonzalo]: Waiting to see what would happen. The men begin to narrate when the plane came to a complete stop. They said, “Now people are starting to descend.”

[Massimo]: The first to descend were the crew members.

[Gonzalo]: They were saying a young lady gets off, someone in uniform gets off, maybe a copilot and the pilot and such.

[Massimo]: Captain Molina. Copilot Ramírez. Maria Eugenia, Edilma.

[Gonzalo]: Until they said, “Well, at this point no one is coming out. We’re going to see what will happen to the hijackers; they must be the last to exit.”

[Massimo]: But the hijackers were not leaving the plane. So, someone gave the order to the Army and the police, who were waiting on the runway: get inside the plane and get them out.

[Gonzalo]: But the surprise was . . . when they announced, “The hijackers aren’t anywhere in the plane. What happened?”

[Massimo]: They disappeared. After sixty hours, stops in six countries and 22,750 kilometers traveled, the hijacked plane was not hijacked. It was empty. Of all the possible endings to that night of media anticipation, this one was the most extraordinary. And the crew didn’t say a thing.

But they were going to have to talk. One by one they were questioned by the police. If a few minutes before they were victims, now they began to be suspect.

To understand what happened, we have to go back to the moment when the plane made its last two stops, in Resistencia and Asunción. In each one, as we said, they spent five and eight minutes, respectively. They made several requests to the control towers, and they took off before they could get them.

But they weren’t improvising. Shortly before reaching the first destination, the air pirates revealed to Captain Molina the end of their plan: One would get off one at each stop. And they would take Edilma and María Eugenia with them.

[María]: He wanted us to take off our uniforms, put on our civilian clothes, and go with him.

[Massimo]: They would be their escape insurance. After the last stop in Asunción, the rest of the crew would have to fly to Buenos Aires, and if they said where they had gotten off with the hostesses, their lives would be in danger.

Edilma was terrified when she found out about the plan.

[Edilma]: I was shaken, I remembered my children. My children were young. It seemed to me that they were left unprotected. At that moment I definitely felt very scared.

[Massimo]: María Eugenia was also scared to death. But they didn’t say a word.

[Edilma]: We didn’t dare speak. I just remember that María Eugenia told me, “Perez, we have to do it.” And I said, “Yes, sister . . . ok.”

[Massimo]: In Resistencia, Edilma had to go down first, together with the tall hijacker, the one who had led the operation. So, she went to the cockpit to leave her purse with copilot Ramírez, whom she knew best, because he was a friend of her brother. They had told her not to wear anything that could identify her . . .

[Edilma]: So, Ramírez asked me, “And this?”

[Massimo]: The copilot had not yet heard about the air pirates’ plan.

[Edilma]: So, I told him, “Captain, I’m getting off there in Chaco as a hostage.”

[Massimo]: In Resistencia, a province of Chaco, Argentina. Ramírez looked at her surprised, and replied:

[Edilma]: “You are not getting off and María Eugenia is not getting off. We will all return alive or all dead to Colombia, but no one is getting off.”

[Massimo]: The copilot left the cockpit to speak with the hijackers and told them if they wanted a hostage, it could be him, but that none of the flight attendants would get off with them. For a few minutes, the pirates doubted what to do. The plan would fall apart if the police started looking for them as soon as they set foot on the ground. But the copilot seemed serious.

In the end, the pilots proposed another solution: They would make a pact. If they didn’t take anyone hostage, the crew would commit not to notify by radio where they had gotten off, nor to cooperate with the investigation.

[Edilma]: And the pilots gave them their word that they wouldn’t say anything until they got to Ezeiza.

[Massimo]: That would give them a few hours to get lost.

Little by little, the air pirates were convinced. But before leaving the plane, they made one last threat.

[Edilma]: They said that if we said anything, we had family.

[Massimo]: And they had taken the names and addresses of the entire crew.

[Edilma]: And you know that for . . . for the family, one is willing to give everything.

[Massimo]: You may already be imagining what happened. In Resistencia, they touched down on the runway but didn’t stop the plane. The plane circled around and when it went into a blind spot, the chief hijacker jumped out with half the money.

It was the same distracting maneuver they had used in Mendoza to get the last nine passengers off. That must have been a rehearsal.

Minutes later, they took off again to Paraguay. They did the same at the Asunción airport. When they touched down, Captain Molina asked the runway lights to be turned off. The plane turned around and the second pirate jumped.

Some local authorities, who were observing the plane from the airport, believed they saw a body and thought that the plane had run over someone. Immediately, they crossed the track in two vans, one with police officers and the other with journalists.

But when they got there, there was no one.

When the last hijacker got off, everyone inside the plane celebrated with euphoria.

[Edilma]: We hugged each other, we cried. It was very emotional.

[María]: It was a very emotional moment. We were happy. I remember that I sat in a chair and fell asleep. I finally woke up when we were over Buenos Aires.

[Massimo]: But they knew the arrival in Buenos Aires was not going to be easy. They would have to give uncomfortable explanations.

[Edilma]: We were taking a risk, because the pilots couldn’t say they were flying alone.

[Massimo]: Although it was under threat to their lives and that of their families, the fact is they had helped the hijackers escape.

Once they landed in Ezeiza and the air pirates’ final trick was revealed, suspicion immediately fell on the crew. The police saw them as possible accomplices, and they searched their luggage to see if they weren’t hiding part of the fifty thousand dollars.

[Edilma]: Maybe they thought we had something to do with them, or they had given us money, or whatever.

[Massimo]: The next morning, they were interrogated for another five hours at the airport. As he was leaving, Captain Molina gave his explanations to the press. And I quote, “In their desperation, they said if anyone tried to arrest them, they would kill the flight attendants. To save their lives we reached a gentlemen’s agreement.”

The Colombian press strongly criticized Captain Molina for not having notified by radio that the hijackers were no longer on the plane. Even his father had to give an interview to defend his son. The Colombian newspaper El Tiempo spoke of an “agreement for the air pirates to escape”, and it was true that there was an agreement, but it was reached so that the hostesses who had voluntarily gone up could return home.

[María]: Well, I was relaxed about it, because I knew I was doing the right thing. Because why would you lend yourself for that kind of thing, who would do that with evil intentions, right? It was done in order to . . . to help, to help people, and in the end that was our job.

[Massimo]: Colombian newspapers not only attacked them, they also raised suspicions about some of the passengers, due to rumors that they had been very calm during the hijacking. They also published alleged leaks of the police investigation, such as the pirates had received training in the Soviet Union or Cuba, and they wondered if the name of the place where they had landed, “Resistencia,” might be a coded political message.

Nothing was clear, only that the hijackers had vanished. The Argentinian police had searched the surroundings of Resistencia, but a dense fog prevented them from seeing more than fifty meters away. In Paraguay they set up controls on the border. It seemed too late—the hijackers were hours ahead, they had the money to disappear, and no one had seen their faces.

However, they had left some traces.

There was that closeness with the cyclists, the comments about sports between Lucena and the chief hijacker, and one of them had gotten off in Paraguay and the other almost at the border.

In the city where the hijacking began, Pereira, there was a community of Paraguayan immigrants. They were footballers who had been migrating for decades to play for the local club, Deportivo Pereira. Since the 1950s, a hundred Paraguayan players had gone through the club.

The community was known as the “Paraguayan Pereira.” And there were some suspicious things about it. Gonzalo Valencia, the sports journalist who spoke earlier, met them shortly after the end of the hijacking, when he went with his wife to a restaurant. There they met a former Paraguayan footballer and began to talk about it.

[Gonzalo]: He asked us if we knew who the hijackers were. We told him that nobody in Colombia knew.

[Massimo]: But the former Paraguayan player told them that he did. That many people knew, or at least, there were rumors.

[Gonzalo]: He told us that it was two of their fellow countrymen who had hijacked the plane. And they were newcomers to Colombian soccer.

[Massimo]: Just like that, sitting in a restaurant, Gonzalo heard the names of the two men who had kept the country in suspense for sixty hours.

[Gonzalo]: They were Eusebio Borja and Francisco Solano López.

[Massimo]: Gonzalo couldn’t believe it. It turns out he had met them.

[Gonzalo]: I had talked to them, I once had coffee with them, and never in my life would I have imagined they could pull off such a trick.

[Massimo]: The former soccer player told him that weeks before the hijacking, Solano López and Borja had tried to raise money among the Paraguayan community for a business they were setting up. They had financial problems: They had moved to Pereira to play in the local league, but they didn’t have a team.

When it was known that one of the hijackers had gotten off in Asunción, the people in Paraguayan Pereira became concerned. A crime of this type could damage the good image of Paraguayans in the city.

While researching this story, I spoke with more than thirty people about what happened in those days, and three sources told me that it was probably someone from Paraguayan Pereira who alerted the police.

The truth is that five days after the hijacking ended, the identity of the air pirates was confirmed. In Asunción, the police arrested the shorter one, Francisco Solano López, 31. It wasn’t very difficult either—he was in a house he had rented near where his family lived.

[Gonzalo]: I imagine they saw themselves as heroes. He was so excited and so full of pride that he distributed dollars in the neighborhood where he had lived in Asunción.

[Massimo]: He had twenty left of the twenty-five thousand dollars he’s escaped with. Much of that he had gifted to family and friends. After jumping out of the plane, he waited for day to break at an abandoned train station, and then tried to pay with the dollars for a bus ticket. In the end they gave him a free ride.

After his arrest, he was shown to the press as a trophy by the government of Paraguayan dictator Alberto Stroessner. They photographed him wearing his hood on at the airport runway, where he jumped out of the plane.

Solano López was unrepentant. He said, and I quote, “I was tired of being hungry and miserable, so I decided to hijack the plane.” He also said that the National Liberation Army and political prisoners was part of the script. And the bombs weren’t real, either, just the guns. It was all part of a series of deceptions to carry out the hijacking.

In fact, no traces of the shot that started it all were ever found on the plane. Apparently, they used a blank gun, that is, one that could make a noise like a shot, but without firing any bullets.

[Gonzalo]: The thing was pulled off so well that they managed to elude the security of several countries in America.

[Edilma]: They had it all manipulated and organized. They knew what they were going to do. They had the navigational charts marked. And yes, undoubtedly, they were bandits, ambitious. They wanted money.

[Massimo]: According to Solano López, they did improvise two things—the itinerary of the countries they passed through, and the final destination. He said that the original plan was to get off in Ecuador and disappear, but that the atmospheric conditions and visibility prevented them from getting off at the exact place they had chosen.

It made sense—they were both very familiar with Ecuador. When Solano López was arrested, he said that he had met Eusebio Borja a few days before. But that was a lie—they had been teammates four years before on the América de Ambato team of the Ecuadorian first division.

They were both forwards. They were called “Toro” Solano and “Cacho” Borja. The first one was aggressive, a fighter, and the second, who had studied medicine prior to football, was a more intelligent player. But that year the América was relegated to a lower division and they began to wander among lower-profile teams, that almost always ended up relegated.

They were 31 and 27 years old when they arrived together in Colombia, seeking better luck. But they never found it. Borja, more talented, was somewhat closer. He managed to play a few games for Once Caldas, but they didn´t hire him. The team had a showy style of play, with a lot of passing, and the Paraguayan players had the reputation of being rough.

Solano López tried several clubs, but they didn’t sign him on, either.

[Gonzalo]: He was honestly a low-level player, and he tried to play for Deportivo Pereira, but he wasn´t in good form and they didn’t hire him. He was left up in the air, living next to the Paraguayans, the fellowmen who were in Pereira, but wasn´t able to practice any sports or get a job.

[Massimo]: Shortly after arriving in Colombia, the two were unemployed, and done with their sports careers. From time to time, they played friendly matches with the Paraguayan Pereira players, but they didn’t hang around much with them.

They pretended to have a higher standard of living than they had. They wore fancy watches, and when they went out for a meal, they liked to pay the check for everyone. Where did they get that money? It´s unknown.

The fact is that they were running out of it.

Two years after his arrest, Solano López was extradited to Colombia, where he was given five years in prison. The cyclist Luis Reátegui reports that he visited him while he was serving his sentence, along with a journalist who wanted to write an article about the air pirate.

And it was true what Solano López told him on the plane: They knew each other. On one occasion, he recalls, they had met in a hotel in Pereira and had played a board game.

This is Reátegui, talking about that meeting:

[Luis]: “Loook, look, Reátegui was freaking scared! So were the others!” And he laughed with us.

[Massimo]: It’s hard to know how or when they came up with the plan to hijack a plane. Solano López never said why, because he wanted to write a book. Some say he wrote it in prison and it was called, “I, the Air Pirate,” but it was never published. Maybe they were influenced by finding themselves in Colombia, the second country with the most skyjackings in the world, and by spending so many years from club to club, from plane to plane. It is likely that they might have felt themselves to experts on the subject.

And we know one more thing—something they said several times up in the air, when asking for the newspapers to find out what was said about them. Something that surely was not part of the plan, and that they added as they became more and more famous.

They said it to Captain Lucena, as a farewell:

[Voice]: “We’re very sorry that you’re leaving and can’t join us in breaking the world record for skyjackings.”

[Massimo]: They wanted a feat to be remembered forever.

It is very difficult to keep track of Solano López from the moment he was jailed. In fact, we found no records in the Colombian prison system on when he was released. And in the newspapers, it stopped being news. In Pereira there is a rumor that he died years later, during a bank robbery in Buenos Aires.

Of Eusebio Borja, the chief hijacker who jumped from the plane in Resistencia, nothing else was known, despite the fact that they continued searching for him. It was as if he had never made landfall. Every so often, a new rumor appeared—that he had been seen on a Colombian island, that he had communicated with a person from Paraguayan Pereira, but he was never seen in public again.

Almost fifty years later, if he is still alive and listening to this episode from somewhere, the longest hijacking in the world is still not over for him.

[Daniel]: In the years that followed that hijacking, treaties against air piracy began to be ratified among the different Latin American countries. Penalties were raised and security was strengthened at all airports.

All of this spelled the end of the golden age of air pirates.

Captain Molina and copilot Ramírez, who proposed the “gentlemen’s agreement,” died ten years later. Their plane had problems while taking off and crashed into a factory near the Medellín airport.

To this day, the hijacking of SAM’s HK-1274 aircraft remains one of the longest and most spectacular in world aviation history.

Massimo Di Ricco is an independent researcher. He lives in Barcelona. He co-produced this story with Victoria Estrada. Victoria is an editor at Radio Ambulante and lives in Xalapa, Mexico.

Massimo has told this and other stories about air piracy in Latin America in the book Los condenados del aire – El viaje a la utopía de los aeropiratas del Caribe, published in Colombia in 2020.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Nicolás Alonso and myself. Desirée Yépez did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano, with music by Rémy. Thanks to David Trujillo and Aneris Casassus for their help with this story. And a special thanks to Ismael Torres for lending us his voice for this episode.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Jorge Caraballo, Xochitl Fabián, Fernanda Guzmán, Miranda Mazariegos, Barbara Sawhill, Hans-Gernot Schenk, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.