The New Neighbors | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► We’re here. To stay. Our commitment to Latin America and Latino communities in the United States remains. We’ve accomplished so much together, but there are still many more stories to tell. Support our journalism here.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: Before we begin, I’d like to say a few words about the episode you’re about to hear.

Every story reported is a snapshot of a moment in time, and in this case, it reflects the period before the start of Donald Trump’s second term.

The reporting began in New York in 2022, during a political climate very different from today—one that was less uncertain and undoubtedly less hostile toward the migrant population. Clearly, much has changed since then, and it’s impossible to predict what lies ahead. We are in a time when the dynamics of our continent are being rewritten, bringing changes that impact the lives of thousands of people, including the family you are about to hear from.

Here is the episode.

This is Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Manhattan Island is a world condensed into a width of less than four kilometers. This means that you can walk from east to west in about an hour. It also means that there has never been enough space for so many people, and yet it is everyone’s space.

New York is the metropolis with the most immigrants in the world, and it is also one of the most expensive cities in the United States, two related facts that perhaps help explain why life in this city can be so complicated. Access to housing here is so difficult and so expensive that many immigrants live in large groups in small apartments, even in windowless basements that can flood during storms.

For years, there has been talk of a housing crisis in New York. The affordable housing system is saturated, and although there are creative solutions, such as converting offices into apartments, it is not enough.

In the last two years, a new wave of immigrants has arrived in New York. Estimates say that there are about 200 thousand people from different parts of the world here. Tens of thousands of them are from Venezuela. They are all here looking for their space… in a city with no space.

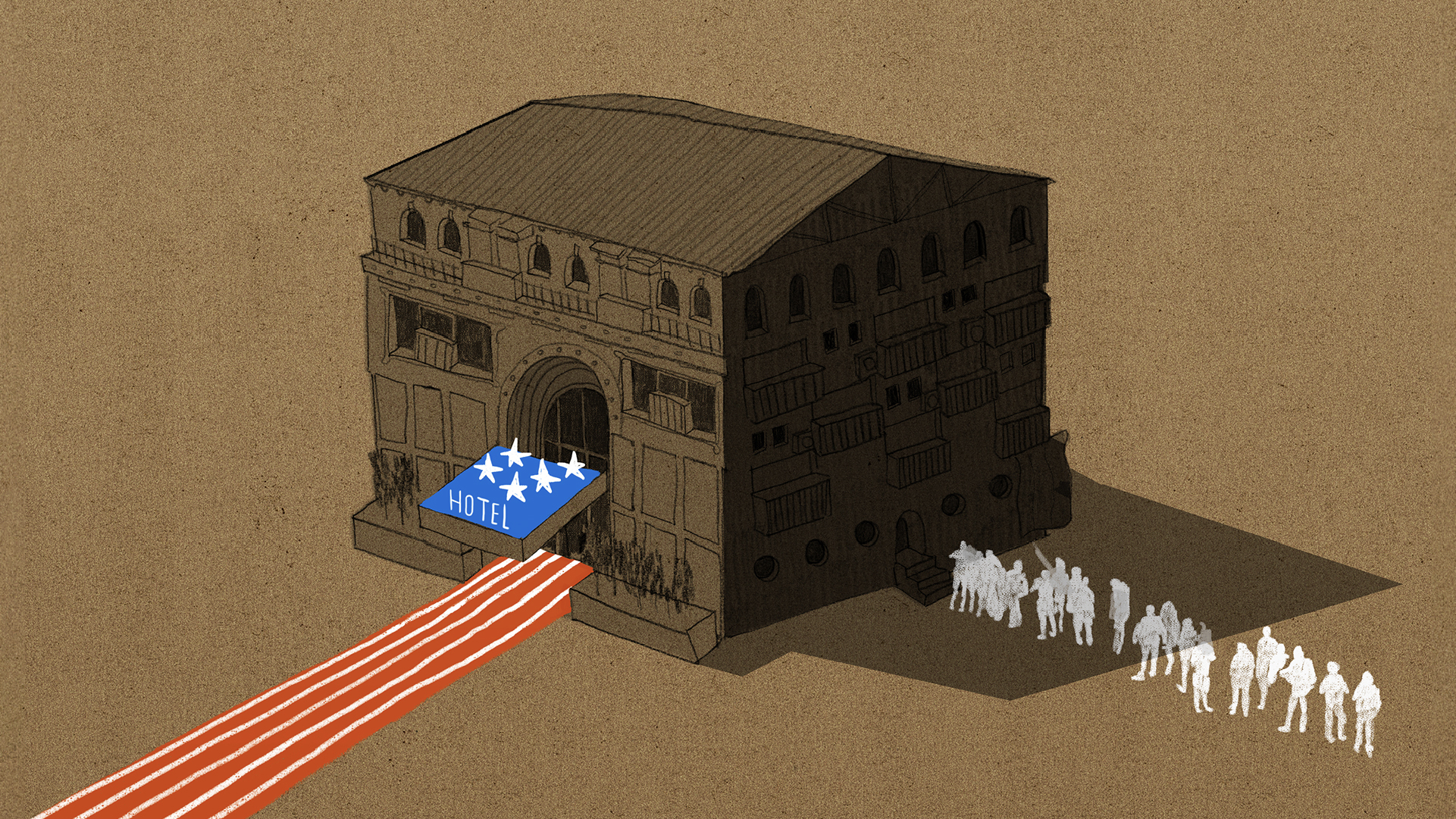

This brings me to our story today, which begins in a hotel.

It is in an affluent neighborhood of Manhattan, known as the Upper West Side. It is a residential area facing Central Park, one of those where buildings have uniformed doormen 24 hours a day. The hotel, an eight-story tower, is hidden among other, more elegant towers.

[Patricia Sulbarán]: Inside, it’s a rather modest hotel. Don’t think it’s a luxury hotel. I think that when it was a hotel for tourists, the cost for a night was around $300, or something like that.

[Daniel]: This is Patricia Sulbarán. She is a Venezuelan journalist and lives in New York. Patricia visited the hotel in October 2022. She was with a 27-year-old Venezuelan woman whom we will call Odalys.

[Odalys]: Put that away, and if you want, we’ll go up to the room.

[Patricia]: Sure.

[Odalys]: But you know they don’t allow visitors here.

[Daniel]: Odalys is not a guest at the hotel. She lives there.

[Patricia]: I am accompanied by her, and there is a security guard at the door. His main job is to take attendance, that is, every time you enter the hotel, he writes down your name and the time of entry and the date, to obviously keep track of who comes in, who goes out, and so on.

[Security guard]: You know, stuff that you cook. Yeah. You can’t bring that.

[Patricia]: Oh, nothing for cooking. It’s okay, sir. Yes, no problem.

[Security guard]: All right.

[Daniel]: It is because of these rules that we will not use Odalys’s real name. Visitors, and especially journalists, are not allowed in the hotel. Odalys could be kicked out of there if they found out she had brought guests. But she wanted Patricia to see how everything worked from the inside. So they went in, and the guard let them pass without noticing.

[Security guard]: Yes. You signed in. Yes, yes.

[Odalys]: Let’s go, then.

[Patricia]: What floor is it? We get in the elevator and come out here, to a very long, carpeted hallway, and I go into the room and she welcomes me to her home and starts showing me around. On to the left there is a TV set…

[Daniel]: The room measures just a few square meters, half the size of a studio apartment. But Odalys lives there with her two young children and her partner.

[Patricia]: Tell me what we are seeing.

[Odalys]: Oh, my God! Two beds. Microwave, fridge, bathroom, the door…

[Patricia]: It’s kind of dark. This room is slightly dark.

[Odalys]: I keep my stuff in the corner and I keep my room clean, because otherwise…

[Patricia]: They’ll throw you out, right?

[Odalys]: You’re out.

[Patricia]: It seems they are strict here, aren’t they?

[Odalys]: Yes.

[Daniel]: The hotel’s common-area cleaning staff could check the room at any moment to make sure everything was in order. There was a lot at stake.

Odalys and her family came to New York in August 2022. They had only two suitcases and two backpacks. When Patricia visited her two months later, the passage of time was noticeable in the room. Now they had the things you have in a home: clothes, toys, several pairs of shoes…

The space between the bedroom door and the entrance to the bathroom was blocked by a baby stroller; the table where the television sat was taken up by notebooks and school crafts next to a carton of juice, a sandwich roll, and a small fruit tray. A photograph stood out, showing Odaly’s youngest son smiling and holding a sign that said “first day of pre-kindergarten;” his clothes were stored in large black bags stacked in the corner, next to the only window. A tricycle was parked next to the microwave.

[Patricia]: I remember being shocked at how small the room was. I think it must be difficult living together like that. You have no privacy. It doesn’t exist.

[Daniel]: This hotel is one of 200 shelters that New York City set up two years ago, most of them in Manhattan, to house the thousands of immigrants who have arrived from the U.S. Mexico border. Many of them were sent to the city on buses arranged by the Texas government, in some cases without knowing where they would end up.

The city has to guarantee shelter for everyone. This has been the policy in New York for more than forty years, but the New York shelter system is very complex and has suffered from budget cuts and overcrowding for many years.

And with the arrival of Odalys and her family, and tens of thousands of others like them, the system collapsed.

So the government improvised: it set up tents in parks across different parts of the city. They also placed people in schools and churches. And some, like Odalys, ended up in hotels.

We wonder: How does it change your life when a hotel, a place of passage, becomes your home?

After the break, we’ll be back with the story

[Daniel]: We’re back. Patricia continues the story.

[Patricia]: The fact that Odalys took the risk of letting me into the hotel seemed brave and a little mischievous at the same time. Before going in, I told her, “Think about it carefully,” but she was determined. And just as she made that decision that day, she had made many other risky, tough decisions in her life, some even impossible to imagine for a 27-year-old.

The day I was in her room was also the day I met her. We are more or less the same height, close to one meter sixty. Odalys has velvety brown skin, without a single freckle or mole. She has a curtain of straight, abundant, shiny hair, like a Miss Venezuela.

In the short time we were in the room, I discovered that Odalys did not go unnoticed. I think, in fact, that the guard let me in part because Odalys distracted him with her friendliness. She was chatting with everyone.

[Odalys]: Oh, he is a short one, isn’t he?

[Woman]: No, he is tall.

[Odalys]: Is he tall? Oh, you mean the man, the mister.

[Woman]: Uh-huh.

[Odalys]: He is a little older.

[Patricia]: We left the hotel and I went to interview her in the park before she had to pick up her children from school. But it was difficult, because she started talking to her other neighbors from the hotel who were sitting on some benches getting some fresh air.

[Odalys]: Look at you sitting there with a big belly. What do you say, girl, is it a girl or a boy?

[Neighbor]: I don’t know. They did the test…

[Odalys]: You don’t know…

[Neighbor]: They haven’t told me.

[Odalys]: You tell me, girl.

[Patricia]: At the time, Odalys had been living there just a few weeks, but she already knew who was pregnant, who lived on which floor, who had a doctor’s appointment, and which children were doing well at school.

[Woman]: You are a gossip.

[Odalys]: Look, I’m going to take off my shoe. I’m not a gossip. I’m a communicator. Communicative.

[Patricia]: And being communicative, as she says, made people talk to her, tell her things about themselves.

And the topics they discussed that day gave me the feeling that this new neighbors community was growing closer. Almost everyone had arrived at the same time and had crossed the same jungle to get here. So they alerted one another whenever something bad happened to a neighbor.

For example, one neighbor was recovering from a miscarriage, another had had an electric stove confiscated when she tried to smuggle it into her room, and some children had gotten sick from the food that was given out for free at the hotel. Often cold sandwiches.

Odalys listened and asked questions, as if she were taking mental notes. Later I would understand that this was part of her role in this growing community. But that day, we said goodbye because she had to pick up her children.

[Odalys]: I miss them. I’ll pick them up at 2:30.

[Patricia]: To understand why Odalys ended up in that hotel room, we have to go back in time to 2017, when she left Venezuela with her eldest son and her partner, whom we will call Kevin.

If that was not the worst year of the Venezuelan crisis, it was one of the worst. Inflation was at 2,600%. There was no gas, no water, no electricity. And this difficult situation unleashed a wave of protests that left more than a hundred dead.

Odalys and Kevin met while working at a shopping center. She had grown up with her single mother and three siblings. And she had her first child when she was 18.

Kevin came from a family with a mother who was a librarian and a father who had retired from the army. And he had a degree in computer engineering. He told me that he also worked on the side putting up posters for an opposition party.

When Odalys became pregnant with her second child, the excitement of becoming parents together for the first time ended in despair. Odalys’s pregnancy was high-risk. They are both from Maracay, a city less than two hours from Caracas. And here we have to understand something: Compared to the rest of Venezuela, the capital has always been a bubble.

For Odalys and Kevin, it was very difficult to pay for medical treatment during her pregnancy, and they couldn’t even get medicines.

And so it was with other things, too. If the economy and public services were collapsing in Caracas, in cities like Maracay it was even worse. Many young people from all over the country felt that there was no hope of any improvement. That there was no future. And according to the United Nations, in 2017, the year Odalys and Kevin left, more than 2 million people fled Venezuela.

That same year, Odalys and Kevin arrived in Quito. Odalys intended to become a naturalized citizen through one of her grandmothers, who was Ecuadorian. While there, she gave birth to her youngest son and got a job in a factory.

[Odalys]: I worked for the man, I worked well for him… the way I worked, I turned out to be a very good worker. I put a lot of effort into my work. I really do, because ever since I was a little girl, I saw my mother earning the money to be able to provide for us. And my mother was a single mother with four children.

[Patricia]: Gradually, they put down roots, making friends. In fact, Odalys’s children became so fond of her boss that they began to call him Grandfather.

But the plan to become a citizen was cut short when Odalys realized that she did not have the necessary documents. She would have to return to Venezuela to get them, and that was not an option. And then the pandemic hit. Many people were left without a job. And with no options, Odalys and Kevin thought, “Well, we have to move again.” They said goodbye to their people and started all over again. This time, the plan was to get to the United States. But they would have to walk.

Odalys told me about her trip to the United States while sitting on a bench in Central Park. She was there with a friend, a neighbor from the hotel. The other voice you will hear is hers. The two of them had crossed the Darien Gap to move between South America and Central America.

[Argelia]: When I left for Panama, I…

[Son]: They heard a tiger.

[Argelia]: They say they heard something like: “Aaahg”.

[Odalys]: Yes, me too.

[Argelia]: You did?

[Odalys]: Yes, the monkeys, the trees too, made a lot of noise to get you to come out. You know, those creatures are wild.

[Patricia]: They knew that at times they would have to carry the children on their backs, so they went into the jungle with the lightest baggage possible. They carried only what was necessary—with one exception, and that is the first thing Odalys remembers about the entire journey. They carried a blue hedgehog, her son’s favorite stuffed animal. So they walked with the stuffed animal the whole time, until at a river crossing the stuffed animal got soaked and began to weigh almost as much as the child himself. They said goodbye to the toy and kept going.

But Darien is a tough place. And Odalys felt that nature was defeating her. At one point, she became seriously ill. Fever, vomiting… She felt like she was done, that there was nothing she could do, and she gave up.

And lying there in the jungle, she said to Kevin, “Leave me here and you go on.”

[Odalys]: “Take good care of my children.” I told him, “Take care of the older one as if he were yours. Don’t let him get lost, don’t let either of my two children get lost.”

[Argelia]: But were you out of the jungle yet?

[Odalys]: No. I couldn’t go any further; I didn’t even have the strength to open my eyes.

[Patricia]: Kevin had a little serum stored in his bag. He gave it to Odalys to drink.

[Odalys]: He is very sentimental and he would cry, he would grab me. “Please don’t do this to me. Come on, I beg you. Come on. Let’s go, you can do it. Look, you’re a warrior; we’re almost out.”

[Patricia]: Odalys begged Kevin not to tell the children under any circumstances that she had died in the jungle.

[Odalys]: “Make up whatever you want, but don’t put them through that pain.”

[Patricia]: But the guide encouraged her, saying they were close, that they were almost there.

[Odalys]: He meant that we were now five minutes away from leaving the jungle and reaching the place they call El Abuelo, where there is food.

[Argelia]: Were you near Platanar?

[Odalys]: Where there is water, where there is water. And we were five minutes from the center. And I say to him, “Liar. You are a liar,” I tell him, lying on the ground. And he says….

[Argelia]: Still dead.

[Odalys]: And he says to me. And he says to me, “Yes, yes, yes, mi abuelo, abuelo. Okay, come on, come on. Get up, get up, let’s go.”

[Patricia]: She stood up and finished the journey. Or at least that stretch of the GREAT journey that would now take them across Central America and Mexico.

After three months walking across the continent, finally, in the last days of August 2022, the family arrived at the U. S. border.

[Odalys]: When I finally came in, I was in shock. When I was coming in, they said, “You made it. Welcome to the United States.” And everyone was crying because of all the sacrifice and effort that they had made, that we had made, and crying out of happiness. Thinking that we were not going to suffer any longer, that we were getting help.

[Patricia]: And, thanks to a connection made by the shelter where they arrived, she and her family got on a plane for the first time and headed to New York. Now the hotel was their refuge. Odalys arrived sick and exhausted. At the hospital, she was told that she had caught parasites in the jungle, but she recovered after hours of sleep. After a month, she started noticing who her new neighbors were. At first glance, she counted families from Ecuador, Cuba, Nicaragua. And many people from Venezuela.

Migrants like her, who came seeking asylum in the United States, had many restrictions finding work. First, they had to present their case in immigration courts to obtain legal permits to work. But Odalys and Kevin had mouths to feed, so they found informal work in a restaurant.

At the hotel there were strict rules. There was a curfew, and a list of who came in and out. They were not allowed to use electric stoves because of the risk of fire. But this meant that cooking was not allowed. So almost all the money they earned was spent eating on the street. And there came a point when the adults ate only what they ate at work—junk food—and saved up to buy healthy food for the children. Eggs, potatoes, milk. At some point they would have to leave that hotel.

Not everything was bad or stressful. Odalys was starting to make friends.

Meanwhile, the hotel was filling up with more families. And it was not the only one. Since Odalys arrived, more than 130 hotels in New York signed contracts with the city government, hosting in all more than 65 thousand migrants. Each hotel received, on average, about 200 dollars per room per night.

The new arrivals had a lot of needs, from cell phones or cards with credit for the subway, to coats because winter was coming, strollers for babies, even pants.

Most people arrived after days or months of crossing mountains and jungles, climbing on the roofs of trains, and walking a lot. They had lost weight and their clothes didn’t fit them. Many didn’t even have a change of clothes.

Now in New York, many of these people didn’t even know how to look for a job, or how to enroll their children in school, and they were struggling to understand how to get the paperwork to fix their legal situation. But Odalys was one of the first to get organized.

[Odalys]: The neighborhood council began because there were concerns about food, there were concerns about winter clothing, there were many concerns about many things they didn’t have.

[Patricia]: Odalys helped conduct a census of the hotel’s population and collected lists of everything that was needed. At the same time, she got in touch with neighbors outside the hotel, people who had lived in the neighborhood for decades. And from there, networks of volunteers emerged who, in their free time, accompanied the families and served as translators for them at medical appointments and immigration offices. Donations were also received. And all of this was done through a WhatsApp group. It was a new community.

And having a tribe was no small thing. New York is… difficult. It’s very fast-paced, everyone is busy, everyone has to survive. But this community also faced a very specific challenge. Because in the city, the idea was beginning to form that the immigrants who arrived were unwanted, that there was simply no room for them. The mayor of New York himself would declare, a year later, that the arrival of the migrants “was going to destroy the city.”

[Archive soundbite]

[Mayor]: This issue will destroy New York City, destroy New York City.

[Patricia]: Odalys and I agreed to stay in touch. I wanted to see what she could accomplish with that neighborhood council and how she would fare in the city. But a short time later, I got the news: New York authorities were moving the families out of the hotel. Within days, the space that housed this community would be empty.

My first thought was: What will happen to Odalys?

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Patricia Sulbarán continues the story.

[Patricia]: It was a Thursday in November, 2022, when the hotel residents were told that they were going to be transferred to different shelters.

No one understood why this was happening or whether they could stop it. They were worried about the children, about the schools they were enrolled in, which were nearby. They were worried about work… But there was not much room to negotiate.

Two days after the announcement, buses arrived to pick up the families and distribute them to other shelters around the city.

With this forced separation came the inevitable: the neighborhood council, the one led by Odalys, fell apart.

Many people who come to New York are fleeing something. In the case of Odalys and me, we fled a country in ruins.

Since we left Venezuela—she left in 2017 and I left in 2014—until today, almost 8 million Venezuelans have left the country. And we all have a shared story.

When I learned what had happened at the hotel and tried to contact Odalys, I discovered that she no longer had the same phone number. It took me months to get the new one, and in February 2023, I contacted her. They were still in the hotel and they had no winter clothes. February is one of the coldest months in N.Y., so I brought them some jackets and a coat. We agreed to meet very soon. But I couldn’t do it, because I was faced with my own parents’ migration. The experience was so overwhelming that I had to devote my time to helping them.

Leaving your country when you are over 60 is no small thing. And I think it wasn’t easy for them, or for me.

With my mind busy with my parents’ move, I didn’t realize that six months had passed since I had last spoken to Odalys. It was now August, 2023.

[Patricia]: Hello?

[Odalys]: How are you, Patricia?

[Patricia]: Hello, it’s good to hear from you. How are you?

[Odalys]: Fine, Patricia.

[Patricia]: Odalys told me that very few families had stayed at the hotel since that day of the mass move.

[Patricia]: Are you still in New York?

[Odalys]: Yes.

[Patricia]: Oh, cool. And you’re living in the same hotel?

[Odalys]: Yes.

[Patricia]: Odalys didn’t know why exactly she and her family had been allowed to stay, but that’s what happened.

And still the kitchen situation and all that. I imagine it’s still the same, right?

[Odalys]: Yes Patricia, that’s correct. We cook in the microwave. There are some dishes, some things I can cook in the microwave so that vitamins don’t get lost in the process. Because I cook in the microwave.

[Patricia]: That part is really hard, when you think of your nutrition and that of the children, right?

[Odalys]: Oh Patricia, if you could see us. Patricia, we are so fat, Patricia…

[Patricia]: Sometimes they could borrow the kitchen of a neighbor who lived nearby. But aside from that, what they ate most of the time was junk food combos, their work food. We agreed to meet at the park the following day.

[Patricia]: See you tomorrow, then.

[Odalys]: OK. See you tomorrow.

[Patricia]: Kisses. Take care of yourselves.

[Odalys]: Kisses. You too.

[Patricia]: How old are you? You have to tell me because it’s a microphone.

[Gilbert]: Six, six.

[Kevin]: Five.

[Son]: Five.

[Patricia]: This is the youngest boy. We’ll call him Gilbert. He’s missing all his front teeth, but he still talks a lot.

[Gilbert]: Look, look, look, look, look, look. Friend, look.

[Patricia]: Gilbert turned four during the trip, while the family was in Costa Rica, so he started going to school for the first time once they were in the United States. Odalys says that everything was new and, of course, it was hard for him to adapt. But after a few months, he began to feel comfortable speaking English.

The oldest child, I’ll call him Oscar, was 8 years old when they came to New York. He was about to start fifth grade. He’s the opposite of his younger brother: much more serious, but just as sweet. One of the most vivid memories he has since he arrived is, of course.

[Oscar]: Snow!

[Kevin]: It was your dream, wasn’t it?

[Odalys]: They built a snowman.

[Oscar]: A tiny one.

[Patricia]: Kevin showed me his tattoos of his children’s names. He had a sunburn because he switched from working at the restaurant to working in construction. He said the pay was better at the construction site.

[Kevin]: That’s the way I am: wherever the best opportunity comes up, I take advantage of it, I go right away.

[Patricia]: One of his goals was to provide financial help for his parents, who still live in Venezuela.

[Kevin]: I struggled so hard to get here. It’s a country where you earn money and in spite of it all, you can stretch the money. Do you know what I mean? I can make it go a long way because I know how to manage money, it goes a long way, you see the results. Not like those Latin countries where you earn money and you never see it.

[Patricia]: But they did have one expense in particular that weighed heavily on them: the immigration lawyer.

[Kevin]: We want to become independent, but everything works out in God’s time, because right now, with the expenses we have right now, it is difficult for us.

[Patricia]: What are the main expenses here?

[Kevin]: The lawyer, the lawyer, the lawyer. Yes, they take half of our salary in one week.

[Patricia]: The lawyer would charge them $20,000.

[Odalys]: It’s important to do things right, you know, to do things they way they’re supposed to be. So that they don’t say, “No, these people are here illegally, they’re staying, they’re doing whatever they want, they’re not paying taxes,” or anything like that.

[Patricia]: I said goodbye and we agreed to meet the following week. It would be a special occasion: Kevin’s birthday.

When we met again, I noticed that, although it was supposed to be a joyful occasion, Odalys seemed sad. When we were on the subway on the way to the restaurant, I tried to start a conversation with her. You could tell from her voice that she was depressed.

[Patricia]: And how has the room changed since you showed it to me?

[Odalys]: The same.

[Patricia]: Is everything the same? And how have the people who live in that hotel changed?

[Odalys]: I don’t know anyone there, only the people downstairs who let us in, and that’s all. Because I don’t talk to anyone. I don’t know anyone. Because they moved all the people out.

[Patricia]: The two boys spent the day trying to make her laugh, but Odalys wasn’t in the mood.

After lunch, we went to buy a birthday cake for Kevin. The two of us went into a bakery in the heart of Chinatown alone. And standing in front of a fridge, looking at cakes, I finally understood what was happening to her.

I wasn’t recording at the time, but Odalys told me, “I feel dead inside.” She couldn’t forget that they could be thrown out of the hotel at any moment. And then, what would happen to her little family?

It was all over the news. The mayor was saying constantly that there was no room in the shelters. And there was already a plan to expel some migrants. The New York government had even left pamphlets on the Mexican border, telling people, “There is no room for you in New York. Go somewhere else”.

“I don’t know,” Odalys, who was not yet 30, told me, “but I think I’ll be 35 and still be stuck in that hotel.” The little they managed to save seemed useless to her.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Patricia continues the story.

People come to New York from all over the world. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city welcomed more than a million people from different countries. They were fleeing famine, violence, and persecution. By then, New York was already a great metropolis, the second largest in the world after London.

Immigrants quickly joined the economy and transformed New York into the cosmopolitan city we know today. But even in those days, living well here, and by this I mean having access to stable, comfortable housing, was a big challenge. Today, prices have skyrocketed so much in recent years that the gap between those who have and those who do not has become even wider.

But there are longings that unite the newcomers, and it doesn’t matter who they are or where they come from. For many people here, New York remains a place of possibilities. Even if they occasionally ask themselves, “Is it worth it?”

I wanted to ask Odalys this question, so we met three months later. It was November 2023, and the leaves on the trees were drying. A cold breeze was blowing, a sign of winter. I remembered it had been more than a year since we had met.

Odalys came down to the hotel door to meet us.

[Patricia]: Hey there.

[Odalys]: How are you? Sorry I took so long, but…

[Patricia]: It was starting to get dark, and the cold was getting very harsh, so we did our catching up quickly. The good news: Odalys was making progress with her immigration case and was now just waiting for her social security number to arrive, which would allow her to access a better job.

[Odalys]: We are giving up a lot of things so we can save up that little bit of money for rent.

[Patricia]: What are you doing? What are you giving up?

[Odalys]: Eating well.

[Patricia]: The same deal as a year ago still applies. Adults eat whatever they can, and the most nutritious food is for the children.

[Odalys]: Sometimes, the older one says, “Mommy, eat,” he says. “No, you eat,” I say, “look, the one who has to go to school has to nourish his mind. Don’t worry about me. I’ll eat at work.”

[Patricia]: Maybe it was because Christmas was just around the corner, and in a few weeks the city would be filled with lights and decorations. Or maybe it was the fact that Odalys was still here to see her second Christmas in New York, but in her voice and her attitude I could tell that she hadn’t given up. And now I felt a renewed optimism, as if her life was going to get better very soon.

Before we said goodbye, Odalys told me that one afternoon she asked her children to write letters to Santa Claus.

[Odalys]: And the first thing they said was they want a room, a new bed, they want a house. They no longer asked for toys; they asked for a house. They are the ones who feel uncomfortable; they are the ones who feel trapped. Crushed, I don’t know. I told them to be patient, because it’s going to happen eventually.

[Patricia]: Are you sending money to Venezuela?

The end-of-year holidays arrived, and I didn’t hear from them again until February 2024, when Kevin contacted me.

[Archive soundbite]

Today is February 29th. I just got to the office and I was texting him and he told me that they decided to leave New York. They are going to leave the state, he said. “We are leaving only because the rent is very expensive and it has been very difficult for us. We have to leave the hotel. We want to leave the hotel.” It’s easy to empathize with someone who has been in that situation for two years, living with no kitchen, with no space, with a curfew, working at night. I mean, it’s too much.

Shortly after recording that voice note, we spoke on the phone:

[Patricia]: And when did you decide that?

[Kevin]: A week ago. We don’t have enough for rent here, because the rents here cost $2,500, $2,800. And I’m not going to rent a one-room apartment. There are four of us.

[Patricia]: It’s hard to hear clearly, but he tells me that rents in New York at that time were $2,500, $2,800 a month. They can’t afford to pay that for a one-bedroom apartment. They are a family of four.

[Kevin]: Listen, I know that everyone’s situation is different, but half the people we’ve met have left New York for other states. They seem to be comfortable in the sense that they live in their house. they have a car at home, a job to pay the rent. But there’s nothing more comfortable than being in your own house. With no one telling you what time you have to come in or go out. Here, we can’t even cook to eat.

[Patricia]: After talking to Kevin, I thought that was the end of the story. New York was no longer a good idea for them. They were going to try their luck somewhere else. Somewhere they could build a life.

I wanted to see Odalys one last time. To close our cycle. But I ran into something that surprised me. That drastic and definitive decision to leave—well, they had thought it over.

[Patricia]: This is the card, right?

[Odalys]: Yes.

[Patricia]: There you have to enter the username you had created and the password again…

Do you remember when Odalys told me that they were waiting for their social security number to arrive? Well, in March 2024, which was the last time I interviewed her, I accompanied her to a bank to open an account with her new social security number. The family had decided not to leave New York.

Having a bank account and a social security number gave them the option of qualifying for a so-called housing voucher, which is basically a document for low-income people and families to access housing in New York. And even though that system is also saturated, for Odalys and Kevin it was something to hold on to.

When I met Odalys, she was afraid of the subway at night and didn’t dare to communicate in English. But the Odalys I was seeing now…

[Patricia]: What did we do today? You can summarize.

[Odalys]: Well, all kinds of things… Bank account. Doctor’s appointment for the boy…

[Patricia]: And now?

[Odalys]: Go get my children.

[Patricia]: From afterschool.

[Odalys]: That’s right.

[Patricia]: We went into a community center and waited for the children to leave the child-care center, where they spend their afternoons doing homework. The youngest one was the first to come out.

[Odalys]: Say hi, now.

[Gilbert]: Hello.

[Patricia]: How are you?

[Gilbert]: I’m fine.

[Patricia]: Let’s see. Your shoes aren’t the Nikes.

[Odalys]: No, I made him wear them. That’s another story.

[Patricia]: A few minutes later, the older one came out.

How did it go?

[Oscar]: Fine. I did my homework. All of it.

[Patricia]: This was the routine. Odalys waited for them, greeted them with a kiss, and when the gang was complete, they said goodbye to the receptionist at the center, whom they affectionately called “chula.”

[Receptionist]: Bye. Bye, guys!

[Child]: Ciao, chula!

[Receptionist]: Bye!

[Patricia]: We hit the streets of Manhattan and the kids dominated the conversation.

[Oscar]: Just the way my brother likes it.

[Gilbert]: Yes, it’s called chicken.

[Patricia]: The four of us were walking, watching the evening fall while we talked about everything and nothing at the same time.

That day I found out, for example, that Odalys had bought the basic supplies to learn how to become a manicurist. That she was trying to get those imitation Nike shoes that she was obsessed with, that she had recently given her oldest son a bracelet to match one she wore. And that sometimes, when everyone arrived at the hotel very tired, they fell asleep hugging each other in a single bed.

[Niño]: When my mom goes to bed and she is warm and cozy, my mom does this to me… [Laughter] And to my brother with one arm and to me.

[Odalys]: It’s just that I’m cold and I’m looking for someone warm.

[Patricia]: We got to the hotel door, and I said goodbye. I’m leaving.

[Daniel]: In early February, the U.S. government announced the end of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for 350,000 Venezuelan immigrants. TPS allowed people who have arrived in the U.S. fleeing disasters or conflicts in certain countries to work and live legally, though only for a limited time. With Trump’s new measure, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans will be subject to deportation.

Although Odalys and Kevin had applied for asylum, they also requested TPS protection in 2023 and are affected by Trump’s new order. Kevin told us he feels anxious about the uncertainty that the political situation has created for people like him and his family.

Patricia Sulbarán is a Venezuelan journalist and audio producer based in New York. This story was edited by Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas, and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano with original music by Rémy.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Adriana Bernal, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Ana Tuirán, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Desirée Yépez.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

If you enjoyed this episode and want us to continue doing independent journalism about Latin America, support us through Deambulantes, our membership program. Visit radioambulante.org/donar and help us continue narrating the region.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.