Translation – Nohemí

Share:

Translation by: Patrick Moseley

[Daniel Alarcón]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Now that we’re part of NPR we want to play some of our favorite stories for our new audience. So, let’s start here.

[Nohemí]: The first memory I have from when I was little was when I arrived to Bogotá. Before that I don’t remember anything. I must have come with somebody but I really don’t remember who it was that brought me.

[Daniel]: This is Nohemí and this memory is from when she was 7 or 8 years old. She went to Bogotá from what we believe was her native town, in Tolima, a state in the central-western side of Colombia.

[Nohemí]: I certainly had never ridden in a bus, because it smelled strongly of gas and I got dizzy, I threw up, I was feeling really bad.

[Daniel]: Today Nohemí. Camila Segura, Radio Ambulante’s Senior Editor, researched and produced this story.

[Camila Segura]: Nohemí doesn’t remember much more. She doesn’t have any memory of her mom, or her dad, or any of her relatives. Years later she found out that a supposed uncle had given her to the military mayor of Anzoátegui, a town in the Tolima, in the years 63 or 64. A gentleman called Vitaliano Sánchez. Vitaliano gave her to his mother-in- law, Doña María.

[Mónica Sánchez]: My father brought her for my grandma. She was a present he brought to her from where he was visiting.

[Camila]: This is Monica Sánchez, Doña María’s granddaughter and Vitaliano’s daughter. She is one of the main characters in this story, but let’s go back to Nohemí and what she remembers after she arrived to Bogotá.

[Nohemí]: When I arrived, I went to a neighborhood called Los Alcáceres and saw that witch. That woman was terrible, she was a witch, a witch.

[Camila]: The witch Nohemí is talking about is Doña María, Mónica’s grandmother. She is the first person Nohemí remembers from that part of her life; and that immense house is the first place she remembers clearly. On that day, Doña María explained to Nohemí she was going to be in charge of all the housework and was to get up around 4 or 4:30 in the morning/

[Nohemí]: I remember clearly that in this house, the first day I arrived, I peed the bed. Then of course, as you can imagine, the bed was a total mess, full of pee, so the first thing they did was get me up and put me inside the washboard, and hit me for being dirty and hit me more for being dirty, and why did I have to pee in the bed and this and that…yikes…Doña María used to give me some tundas, My God.

[Camila]: Tundas which means beatings. Nohemí received, from the first day, lots of beatings. Beatings because she peed the bed, because she didn’t clean well, for just about anything. In this house she lived about one year but she didn’t always live there. Doña María used to lend Nohemí to relatives who didn’t have a maid. Mónica tells me:

[Mónica]: She was the one who started with the whole idea of lending her, so she would lend her to an uncle who didn’t have a maid or to her sisters who were old. They will lend her. She was a collective little slave.

Until she came to our house, until my mom said, “This is mine.”

[Camila]: There came a time, then, when Nohemí came to live permanently with the Sánchez family: Vitaliano, his wife Eunice and, at that time, their six children. All of them were younger than Nohemí who was about 9 years old. Mónica was probably between one or two years old at the time.

[Mónica]: For me Nohemí was always there. Nohemí is in my memories since forever.

[Camila]: Nohemí became like a big sister for all the children, especially the youngest ones.

[Nohemí]: I was the one who took care of them, who gave them their bottle, who changed them, who dealt with them.

[Camila]: On her first day, Eunice, Mónica’s mom, explained to her what she was to do…

[Nohemí]: You have to help me with the girls, with the housework, you have to get up early, to make the bottles, to cook the food, to…

[Camila]: Even though the work was hard and she was responsible for taking care of six children, the change for Nohemí wasn’t that bad, because she wasn’t the only kid in the house any more.

[Mónica]: Nohemí was a playful girl, happy, fun, a big joker… uhm, loving. She was like… she was like one us. Especially with the girls, it was a friendship…

[Nohemí]: Maybe because I didn’t have anyone, I had nothing in life, the children were my family, since I was living with them day and night, for me they became part of my life.

[Camila]: Mónica feels that Nohemí, in some way, was her sister. But from early on in her life she noticed the difference in the treatment she Nohemí received from her parents, but especially from her mom, Eunice…

[Mónica]: My mother. Nobody else. My mother treated her bad. That’s the memory I have: she always got some awful beatings, my mom would go into some insane rage for almost anything, because something had come out wrong or just because. We never got beatings, but Nohemí got beatings every day in her life. And some scenes were so horrific because of their inhuman abuse.

[Camila]: Nohemí remembers the majority of the children helping her on what they could in order to avoid Nohemí getting another beating from Eunice.

[Nohemí]: So, when we thought Doña Eunice was coming home, the children, they themselves ran around helping me put away pots and hide them, so she couldn’t see them dirty or hide the mess we had made under the bed just so…they became my accomplices.

[Camila]: According to Nohemí, Eunice never lost an opportunity to hurt her. If it wasn’t physical abuse, it was verbal abuse:

[Nohemí]: She would say: you are a nobody, your mom is this and that and works in the street.

[Camila]: Nohemí was told thousands of times she was in that house, with them, because her mom was a prostitute, a vagabond, someone who had abandoned her because she didn’t love her.

[Nohemí]: I started hating my biological mother. Meaning, I wanted to be as far away from her as possible. Why? Because as time went by I started realizing the situation I was in. And I put all the blame in my biological mother, because of her I was living in such bad situation.

[Camila]: But Nohemí remembers well the day her biological mother went to Mónica’s house asking for her. Nohemí had been living there two years. We are not sure of her exact age at the time, but one can calculate she was about ten years old.

[Nohemí]: I found out because Doña Eunice told me: “and your so and so mother came.” I did get to hear her voice, while she was talking to that lady.

She heard her, but didn’t see her. Nohemí was washing clothes in the shower. She tells me she didn’t dare to come out of the bathroom. She was too scared of Eunice. But she was able to hear what Eunice was telling her mother:

[Nohemí]: But the girl is like one of my girls, she is treated like a queen, she has everything you can’t give her, she is studying, she is the little princess of this house. Of course, this lady left totally convinced that was the truth, that things were like that.

[Camila]: But we know she wasn’t treated as a princess. Psychological abuse, beatings, incessant work – and rapes. Several people, several times.

[Nohemí]: The first was Vitaliano, Mónica’s father. He raped me very young, he must have raped me when I was about nine years old.

[Camila]: And two of Eunice’s brothers: Julio and Edgar.

I ask her if she finds it hard to speak about this horrible thing and she tells me no…

[Nohemí]: Not at all. No, because, let’s see, for me it’s not horrible, you know why? Because for me it was all a game. I was always the maid for everyone so for me it was as if someone loved me. Meaning, at the time I saw it like that, obviously when I became an adult and started understanding life, I understood all of it was bad.

[Camila]: Here I have to confess something. When she told me this, I couldn’t stand it anymore and tears came out. And the most absurd thing happened. Nohemí ended up consoling me. She even offered me water before continuing and her voice also started quivering.

[Nohemí]: [crying] Let’s see, I also had some beautiful moments. Back then, they had a country house in Anolaima full of fruit and there was a river, a creek, and for me it was my only place to go vent, to go and sit there and stay a long time and since I was a little older I was able to… able to cry…And I sat to think, and I would think: why do I have to live such hard life? But really, I thought it was… I used to think it was a normal life for any human being.

[Camila]: She had nothing to compare it to. That was her life, she got beaten. And raped. So the years passed. The majority of people in the neighborhood they lived in – all military people like Mr. Vitaliano – had noticed the mistreatment to which Nohemí was subjected. Nobody said anything, until one day, a neighborhood girl, the daughter of one military man, came to her.

[Nohemí]: She told me one day, “Gosh, Nohemí, are you going to continue living your life putting up with this life?” I told her, “But I, ummm, what…what else can I do?” I didn’t know how to take a bus, how to do anything, nothing. She told me: “Nohemí, do you want to go and work for one of my aunts?” I told her “Sure, let’s do it!”

[Camila]: Nohemí was 14 or 15 years old. At that time Eunice spent long periods of time in the country home and left Nohemí in charge of the house.

[Nohemí]: I would say “God, if I leave and my little girls…” all that love I feel for them.

[Camila]: All the children were at school.

[Nohemí]: My God, I kept imagining the moment the children came home and found the house empty. But for sure I left everything ready, I woke up early, and left lunch ready, clothes washed, everything, everything. I left everything impeccable in case… they found me so they wouldn’t beat me. [Laughs]

[Camila]: The neighbor’s driver picked her up at 1pm, and that’s how Nohemí escaped from the Sánchez’s home.

[Mónica]: It was mostly a relief. I was at the time about 10 or 11 years old and it all came to be a story from the past, right? We pretended to forget it all and…and I thought I had forgotten it but…it’s… something…something I carried deep inside of me, it stayed deep inside all of us. I am sure.

[Camila]: Mónica grew up, without her friend, her semi-sister, and she became the rebel of the family. She fought with her parents all the time, and when she got drunk —alone or with friends— all her rancor and anger came out. In her 20s, she left Colombia and moved to Europe, to live far away from her family. But she never forgot Nohemí.

[Mónica]: I carried all that dirt in the bottom of my heart and it would surge in the most unexpected moments. It wasn’t very often, it was once in a while, but it was something I would end up confessing: this is what my family did, this is what my mother did and this is what we did, because we let it be. That, the confession, always came back.

[Camila]: Monica became an alcoholic for many years, until one day she decided to stop drinking.

[Mónica]: After the detoxification, comes therapy and you have to take out all the dirt. And there, in that process, which lasted several years, came a moment where it became evident the issue of Nohemí was the most serious issue in my life, it was something I had to resolve. [crying] And that’s what I did, my mother had her phone number and…

[Camila]: And she called her.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after the break.

[Kelly McEvers, host de Embedded]: Hey, I’m Kelly McEvers, from Embedded. Bill Spencer works at a coal mine in Kentucky, and when I started to ask him about a future without coal, he knows what I’m gonna say…

So if …

[Bill Spencer]: Coal goes out, I’m done for…

[Kelly]: Coal Stories, on the NPR One App or wherever you get your podcasts.

[Guy Raz, host de How I Built This]: What does it take to start something from nothing? And what does it take to actually build it? I’m Guy Raz. Every week on How I Built This, we speak with founders behind some of the most inspiring companies in the world. Find it on NPR One or wherever you get your podcasts.

[Daniel]: You’re listening to Radio Ambulante, I’m Daniel Alarón. When Nohemí was a girl she was taken away from the town where she was born to live with the Sánchez family, a well-off family in the capital of Colombia, Bogotá.

She was there for years as a domestic worker, suffering all kinds of abuse until she was finally able to escape when she was 15. But fortunately, the story doesn’t end there. Decades later she came across an unexpected ally: Mónica, one of the children in the family that had abused her so much. Camila Segura continues this story.

[Camila]: Let’s back up a little bit. So, for many years, Mónica felt extremely guilty about what had happened with Nohemí. She grew up watching her mom insulting Nohemí and hitting her over anything. And of course, Mónica never did anything because she was only 9 years old when 15-year-old Nohemí managed to escape.

But as an adult, after going through therapy, Mónica kept going back to the issue with her sister Marta. They were telephone conversations that lasted hours. They talked about their parents, their siblings, and many times about Nohemí.

Marta was the only one, out of the 7 siblings, who had talked to Nohemí a few times, so Mónica asked her for Nohemí’s phone number.

Mónica lived in Montreal and Nohemí in Soacha, near Bogotá. One day in 2004 Nohemí’s phone rang.

[Nohemí]: I was just arriving from work when ring ring ring. I answered: “Alo”. “Hi, Mico,” they are the only ones who call me ‘Mico.’ I asked her: “Is this Martica?”, since their voices sound so much alike. She said: “No honey, it’s Mónica.” And I was like: “Oh! No.” Oh, if I’d had bad days, that was the most beautiful day of my life.

[Camila]: They talked for about 4 hours and Nohemí told her everything that had happened after she escaped from her house. After a year staying with the neighbor’s aunt, the owner of the house kicked her out firing his gun- because Nohemí had thrown a party. For months she lived in nearby parks, until one day she left with a guy who paid for a hotel room and forced her to sleep with him.

When the guy stopped paying for the hotel, they kicked her out. That’s when she got her first paid job at a bakery and in that same place —a few months after prostituting herself— she would meet the father of her 3 children: a good man, although their marriage didn’t work out, who paid for her elementary schooling and helped her get a job.

Nohemí told her about all this and more. She shared with Mónica one of her most painful experiences: when her first born son was 16 years old, a stray bullet killed him at school.

They kept talking about everything and Monica told her:

[Mónica]: I told her I was aware of what had happened and about the abuse she had endured. [Crying] And… and that it was something that you just don’t do to other people. It was the first time we said it openly.

[Camila]: They talked about the abuse she suffered at the hands of Mónica’s mother, Eunice, and Mónica felt the need to apologize for what her mother had done.

[Nohemí]: I told her: “Look, I’ve already forgiven everything she did.” She said: “No Mico, it’s not fair for her to have done what she did to you.” And since they saw everything, that’s what bothered them so much.

[Camila]: For a long time, Mónica had suspected that Nohemí had also been abused by her dad. It was something she couldn’t shake off, so during that first call she dared to ask.

[Mónica]: And she told me “No, baby, no, your daddy was very nice…” and this and that and… and no. So I…I believed her.

[Camila]: After that call, Mónica and Nohemí started talking regularly on the phone. Mónica was tired of living in Canada. She felt lonely, guilty and dreamt of returning to Colombia.

[Mónica]: Well, when you are far away you idealize everything, right? So, I started to paint a beautiful scene in my head where we were all going to be together again, live happily ever after and forgive each other about everything.

[Camila]: She shared the idea with Nohemí, since the plan included her.

[Nohemí]: She wanted to build a condominium in Cartagena. And build everyone their own cabin. And have us all go and reunite there. So, I went with the idea, but I know that would never be possible. For starters because, how was I going to live with them? I mean, no. I would be their slave again, and I’m not a slave anymore.

[Mónica]: I started to make a plan in my head which included living with her when we got old, and I would be the one to pamper her and return a little bit of all the love I had received from her.

[Camila]: In 2008 Mónica sold everything and returned to Colombia after living more than half of her life abroad. She arrived to her mom’s, in Bogotá, although her priority was seeing Nohemí, so a few days later she went to her house. She tells me about that first meeting after more than 30 years.

[Mónica]: An emotion, a great joy, and especially a great familiarity. There she told me more things about my mom. Things I didn’t remember. She told me about a horrifying scene where my mother pulled her hair out with…with a brush, in an incredible way. She would sit, grab part of her hair and roll it in the brush, and when she was close to her head she would pull it out.

[Nohemí]: Until my head was covered in blood.

[Camila]: The level of abuse against Nohemí was awful. Shocking, even for Mónica, who grew up in the same house. And there was something else, perhaps more disturbing: in spite of everything, Nohemí didn’t only blame herself, but she also thanked Eunice for everything they had given her, for teaching her how to cook, for giving her food and shelter. Even though they never paid her. Mónica was horrified.

[Mónica]: Oh please, and it’s a lie that they gave you everything, they didn’t give you anything, they took everything from you and they didn’t give you anything!

[Nohemí]: So she told me, “You don’t have anything to thank my mother for. Nothing!”

[Camila]: Mónica spent the next two years in Colombia, trying to reconcile with her past. First with her mom, which she didn’t’ achieve. Then with her dad, and this was perhaps the most difficult surprise of her adult life. She moved to the coast to live with him and she found an aggressive and cruel man. But also, he started telling her stories of drunkenness and women, like if he were talking to a friend from the army barracks. The father she remembered was someone else, and now, she had more doubts than ever.

She talked about it with her sisters, and they confirmed memories of violent scenes. So she called Nohemí again, to settle her doubts, once and for all.

[Nohemí]: So one day she called me and said “Mico, I need you to tell me something. Did my father rape you?”

[Mónica]: She told me: “Yes baby.” She told me: “He did that to me, he raped me. He was the first one to rape me.”

[Camila]: This was a turning point for Mónica. Her question —and mine— for Nohemí was: and why didn’t you ever report the abuse?

[Nohemí]: Do you think they would pay attention to a nameless, poor idiot, who had nothing? Who is going to believe that I’m reporting a prestigious Navy captain?

[Mónica]: So I told her: “Well, now you have me, and if you want we can report them, and I’m with you till the end, but we are going to get to the bottom of this.”

[Camila]: And that’s what they did. They started with something simple: a claim in the form of a letter addressed to Monica’s parents, compiling Nohemí’s story, including all the abuse. This is how that letter begins:

[Mónica]: Mom, dad: The day has come when we think it is unacceptable to continue staying silent about the abuse that destroyed our lives.

I’m talking about that girl that you, dad, took away from her mother and you, mom, enslaved miserably. Her name was apparently María…

[Camila]: Mónica sent each of her parents a copy of the certified letter. And she waited, to see how they would react.

[Mónica]: There was no response to the letter. Nothing.

[Camila]: The day after she sent the letter, Mónica emailed her siblings, her children, her in-laws, and her ex-husband. She sent a copy of the letter she had sent her parents and an explanation of her motives:

[Mónica]: That it was about time we take on the guilt we all carried. That’s what I learned in therapy: you have to face things, go in search of the truth and expose it. The dirty laundry is not to be washed in the house, but rather outside, under the sun, and stretched out, exposed so all the dirt can come off.

[Camila]: Her siblings didn’t take it well. According to Mónica, they thought it was unfair to have to pay.

[Mónica]: They were worried about how much it could cost.

[Camila]: But it wasn’t just about money; but rather their reputation, the name of the family, that’s what her siblings were worried about.

[Mónica]: That’s what they were ashamed of: the neighbors finding out. As if they didn’t already know! There’s that scruffy, abused, beaten girl, always dressed in rags. Who doesn’t go to school, who doesn’t get any medical attention, whose teeth are rotting out. Everyone saw that.

[Camila]: After the negative reaction from her siblings, and since it was obvious that neither Vitaliano nor Eunice were going to reply to the claim in the letter, Mónica asked Nohemí if she wanted to do a tutelage.

A tutelage is a legal mechanism which pretends to guarantee the immediate judicial protection of fundamental rights. The key word here is immediate because – normally – there is a statute of limitations meaning, the time that can pass from the initial violation of the rights.

When Mónica asked her, Nohemí said:

[Nohemí]: “But baby, and, what… or what… I mean, I don’t know anything about that.” And she said: “No, you don’t have to worry about any of it.”

[Mónica]: And so, by having my testimony and my help, it was something else. She said: “If you help me then, of course, I’ll sue them.” I told her: “I think you should, and that is what I have to offer you: my support.”

[Camila]: Mónica contacted several lawyers who rejected the case.

[Mónica]: Since the story was so old. But then I realized that it wasn’t an old story. Stealing her, enslaving, and mistreating her, yes, that’s old; but they continue to do so today, they are violating one of her fundamental rights: the right to know the truth.

[Camila]: The truth Mónica refers to is the truth about Nohemí’s story, about her identity, about her origin. It’s a little bit confusing, but I’ll try to explain it in the clearest way possible:

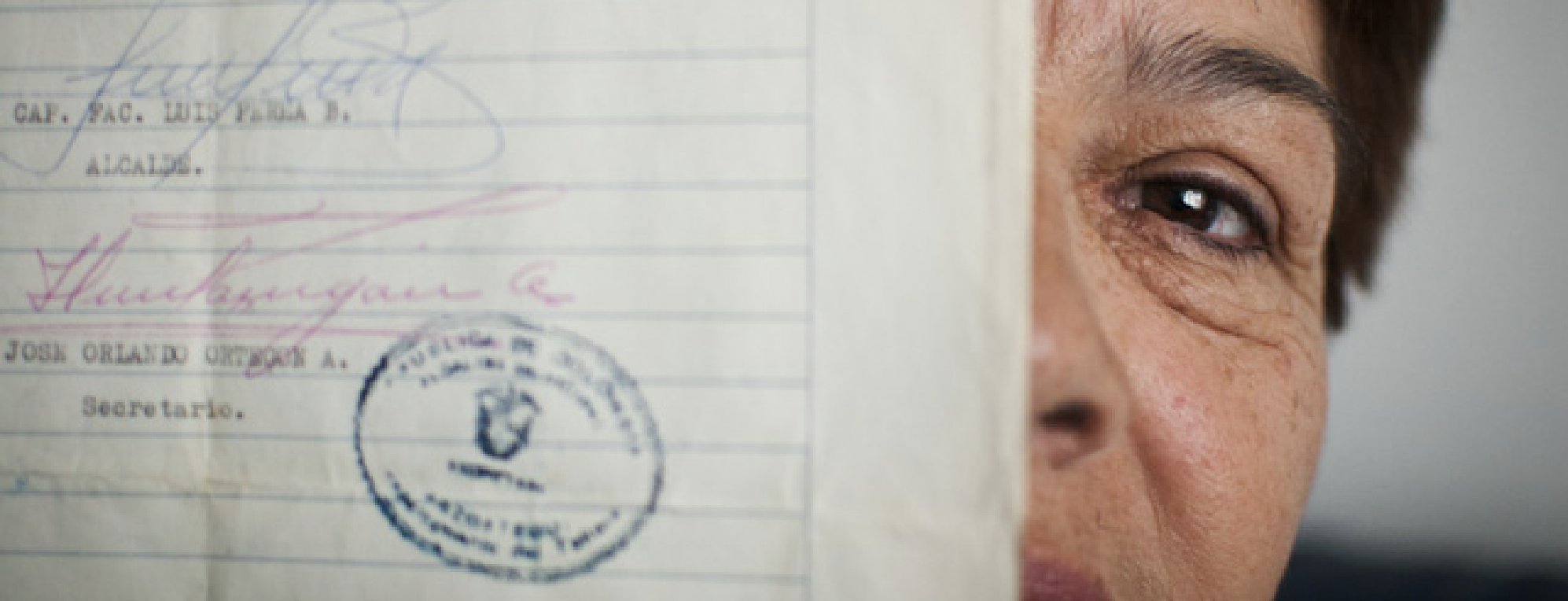

The Sánchez’s always told her that her uncle had intervened so that her mom would give her up for adoption to Vitaliano. But Nohemí found the only document about this alleged adoption in the Sánchez home… And although it shows who we think is her mother —a woman named Rosario Arias— giving her up to Mónica’s grandmother, the document is not signed by her mom —it´s signed by her uncle. And the girl in the document is not even called Nohemí.

When Nohemí was 23 years old she went back to her town and with that document, with the name of her mother shown there, she was able to find her baptism certificate in the town’s church.

[Nohemí]: When I find the baptism certificate, oh surprise, my name is not written as Nohemí anywhere, but rather as María Arias.

[Camila]: Mónica felt compelled to help Nohemí decipher her story, so she continued insisting everywhere possible. She went online, got a template of a tutela document, and wrote the draft herself. A little later she found a lawyer, Ximena Castillo, whom, when she saw what Mónica had written, did not hesitate to take the case. She corrected what Mónica did and got her settled. This is Ximena:

[Ximena Castillo]: We did not mean to revive closed cases in judicial terms for the crime of torture, rape, and human trafficking. But rather vindicate Nohemí as a human being with the right to an identity and a family, the same for her daughters. That is, because Nohemí doesn’t end with Nohemí, Nohemí continues, and Nohemí’s daughters have a right to know where they come from.

[Camila]: They passed the tutela to a municipal judge. Nohemí, Vitaliano and Eunice testified. The lawyer told me she was there only during Vitaliano’s declaration.

[Ximena]: And Vitaliano didn’t accept any of the facts, nor did he show any hint of regret.

[Camila]: I tried to talk to Vitaliano, to Eunice or to one of Mónica’s siblings, but they told me that their lawyer preferred they didn’t make any statements.

In Eunice’s and Vitaliano’s testimonies in court, the phrase “charity work” is repeated several times. Eunice declares that she didn’t treat her as a maid because “who makes a 5 or 6 or 7 year old handle a gas stove that can explode?” And when they ask Eunice how she disciplined Nohemí, she says: “The same way I punished my children: a slap, a shake of their arm.” When they ask Vitaliano about Nohemí’s condition in the house, he replies: “She was considered a domestic worker, not a maid, but someone special that was growing up with us.”

That’s how the Sánchez’s defended themselves and with this first tutela, they won. The judge said the statute of limitations for the crime had already expired.

Nohemí appealed and went back to lose in a superior court, where it was argumented that the delay in claiming showed her lack of urgency when it came to defend her rights. Ximena explained to me these verdicts in the following terms:

[Ximena]: There was a problem of attachment to formality and of laziness of the judicial officers who had the case under their knowledge. There was apathy, indolence, as often happens in this country, where it is common that the law is for those who wear ruana, but not to favor them, but to discriminate against them.

[Camila]: The lawyer submitted an insistence and this one was passed to the Constitutional Court, which on December 12th, 2012, gave Nohemí the right.

The court ordered Vitaliano and Eunice to compensate Nohemí with money. But additionally, it ordered the Ministry of Interior to search for Nohemí’s family and act in order to prevent this from happening to other minors.

The court’s ruling made headlines in all major Colombian media outlets.

(SOUNDBITE FROM NOTICIAS UNO)

[News anchor]: The Constitutional Court ordered a family from Anzoátegui, Tolima to…

(SOUNDBITE FROM EL ESPECTADOR)

[News anchor]: Slavery in the 21st century. Pay close attention, because the Constitutional Court…

(SOUNDBITE FROM CITYTV)

[News anchor]: The Ministry of Interior must find the parents of a woman who, since she was six years, old was taken from her home in Anzoategui and enslaved by a family….

[Camila]: But even though it’s tragic and outrageous, Nohemí’s story is much more common than what we’d like to believe. In Colombia alone there are 750 thousand people who work as domestic workers and everyday there are hundreds of reports of all types of abuse. In this context, Nohemi’s accusations might not be too much of a surprise, what’s surprising is the court’s ruling, which many described as “historic” due to the way it overcame the obstacle of statute of limitations.

A few days after the verdict, Monica’s brothers released a statement where they say that, for them, “the allegations do not make sense” and that “this situation is terribly painful due to its origins and consequences,” as they are seen as “an unpleasant duty to bring them out in the open.” They added that the “real origin of all these accusations is the brilliant intellect, eloquence, and at the same time, serious mental problems of our sister Monica.”

[Camila]: Ximena, the lawyer responds like this:

[Ximena]: Well, I would love for Colombia to have several mental patients like Mónica. People as smart, as supportive and as brave. And with such a sense of responsibility. I would love this to be a country full of that type of insane person.

[Camila]: Now all that’s left for Nohemí is to wait for the result the judge will give in a civil court for the amount she will be compensated with. And without a doubt, for a woman in her situation, that money can change her life. But there is something else much more exciting.

[Nohemí]: I mean, how do I wish I had my mom here and hug her, and have her here laying down, and give her many kisses, and love her, yes I would love to find her. I would love to find her and bring…if maybe she was in a bad situation or something. The past doesn’t matter, what for? What does it matter? But how I would love to have her, to have a brother. In other words, my blood.

[Camila]: And is just that, ultimately, Nohemí’s legal case was all about that, about a girl who never had the opportunity to meet her mother, of knowing nothing about her biological family. And now, with this report the Interior Ministry must give her, perhaps, one day not so far away, she’ll be able to know something of her own story.

[Daniel]: In the past five years, Nohemí —with the help of the Ministry of the Interior— managed to find her biological mother’s whereabouts. They met in August of 2014.

Unfortunately, the meeting wasn’t what she had expected. They aren’t in touch today.

According to the court order, the Sánchez family has to pay an indemnity but Nohemí still hasn’t gotten that money.

Camila Segura is Radio Ambulante’s Senior Editor. She lives in Bogotá. This story was edited by me. The mix and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Jorge Caraballo, Patrick Mosley, Ana Prieto, Barbara Sawhill, Luis Trelles, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Luis Fernando Vargas and Silvia Viñas. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg Pro. Learn more about Radio Ambulante and this story on our website: radioambulante.org.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.