We’re Millionaires [Part One] – Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[David Trujillo]: Hi, I’m David Trujillo.

[Lisette Arévalo]: And I’m Lisette Arévalo, producers at Radio Ambulante.

[David]: Last year we traveled to Guayaquil, Ecuador, to research a story about so-called therapies that promise to cure homosexuality

[Lisette]: We interviewed victims, unearthed documents, and spoke to some of the people who promote these so-called treatments

[David]: It wasn’t easy and it wasn’t cheap to produce the episode. There were several trips, lodging and food costs. Hours and hours searching for archival audio, sifting through tape. And lots of time researching and deciphering local laws.

[Lisette]: You can help us tell more stories like this one.

[David]: Join Deambulantes today, our membership program. Your contribution, no matter the amount, will allow us to keep researching stories in the whole region that need to be told.

[Lisette]: Become a Deambulante today at radioambulante.org/deambulantes. Thank you.

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

[Maribel Valoy]: Look, this is my grandparents’ house. That’s where I lived with my grandparents. Here is where the first meetings started, by this mango tree.

[Daniel]: This is Maribel Valoy Amparo. The story of her mother’s side of the family is key to this story and this town in the Dominican Republic.

[Maribel]: Right now we’re in Cotuí.

[Daniel]: Cotuí, about two hours from the capital, Santo Domingo.

It’s the kind of place where a lot of the neighbors are related.

In Cotuí you see dirt roads, a lot of plantain trees, wooden houses with zinc roofs and rustic fireplaces. Here people feel a special attachment to the land. It sustains them. Most of the families have lived there for generations.

Maribel spent some years in Cotuí as a child and even though she’s lived most of their life in the capital, she never left her town behind completely. She always went back for school breaks. And that habit stayed with her when she grew up. She knows every house and every neighbor as if she had never left.

[Maribel]: Candita, come here! (laughs). That’s Rosario Amparo. How are you?

[Candita]: [unintelligible]… and how are you?

[Maribel]: We’re fine.

[Daniel]: It’s not a very prosperous town. You can tell at first glance. And it’s painfully ironic because Cotuí lies in the shadow of a mountain with a gold mine. Not metaphorically. I’m being literal. Under the mountain, there’s a mine. One of the biggest gold mines in the world. It’s operated by a company called Barrick Gold.

[Maribel]: Look, that’s the Barrick. That’s the… that’s their light, it almost shines on us.

[Luis Trelles]: Where? Where?

[Maribel]: That’s the Barrick Gold, that hill you see there.

[Luis]: Ah, that’s that hill the mine is in?

[Maribel]: The whole… you see all the lights at night.

[Daniel]: That’s journalist Luis Trelles. He traveled to Cotuí early this year, 2020. And he went to investigate a claim that Maribel and many others are making: that the land where the mine is located belongs to them.

In the following two episodes, we’re going to talk about this land, this mine, and one family. About gold, endless wealth, and a rumor that has captivated thousands and thousands of Dominicans.

Luis Trelles along with journalist Mónica Cordero investigated this story.

Here’s Mónica.

[Mónica Cordero]: As a girl, Maribel grew up in a modest home, but she always heard her father say they were millionaires.

[Maribel]: “We’re millionaires in land,” but I was very little. I didn’t really understand. “We’re millionaire’s in land,” he just said it like that.

[Mónica]: In Santo Domingo, Maribel became a stylist and set up a beauty parlor in her home. And that phrase her grandpa would say, “we’re millionaires in land,” fell into the back of her mind. Until one day in November of 2011 she got a phone call. It was an aunt who had emigrated to the Netherlands. Her aunt told her:

[Maribel]: “Maribel, Maribel, we’re the owners of the Barrick”.

[Mónica]: Barrick. That is Barrick Gold, the company that mines Cotuí’s gold. Her aunt wasn’t saying they owned the company, of course, but that they were the owners of the land Barrick was mining.

And that’s because, while she was in the Netherlands, Maribel’s aunt got a call from one of her sisters. One who lived in the Dominican Republic, and who had seen a news story that talked about indemnity rights for lands that supposedly belonged to the families that had lived in Cotuí for generations. And, ecstatic, this aunt called Maribel.

Let’s stop here a moment to give a little context on the mine. The practice of extracting gold throughout the continent began here in Cotuí. The gold that Christopher Columbus saw hanging from the necks of indigenous people, well, came from those mountains.

Many families from Cotuí have stories about how they were taken from their land in the ‘50s, during the Trujillo dictatorship, to mine the gold and they say they never received any compensation. The region, in time, transformed into a community of farmers and ranchers.

In 1975, Rosario Dominicana, a company whose capital was mainly in the US, started operating the mines.

Four years later, the Dominican government acquired all of the company’s stock that was in foreign hands, and the expropriation of the people of Cotuí’s land continued.

Rosario Dominicana shut down its operation in 1999. But in 2002 the government licensed the mine to a corporation that later bought Barrick Gold. To this day, Barrick Gold is the majority partner of the mine.

Barrick Gold initially invested 3.7 billion dollars in starting up the mine, which today produces a little less than a million ounces of gold per year. That is the largest foreign direct investment the island has ever had.

When Maribel got that call from her aunt, she was skeptical at first. She told her she didn’t believe what she was saying. But her aunt asked her to look for her mother’s death certificate.

The plan was to start gathering documents from family members and see what they could do with them later. Maribel, still skeptical, agreed.

[Maribel]: I came here to the countryside. And we got started. So I, with nothing in hand but a little piece of paper, started looking for all the information.

[Mónica]: She got her mom’s death certificate, then her maternal grandparents’, then she came across one belonging to one of her great-great-grandparents.

[Maribel]: That’s when I learned that Jacinto was my great-grandfather’s dad.

[Mónica]: Jacinto. That’s Jacinto Rosario. And that surname is very important in this story.

In fact, it’s what started the whole search for Maribel and her family.

The grandparents of Cotuí are generally the ones sharing legends, and one of those legends says that Jacinto Rosario owned the mine in the early to mid-19th century.

According to them, Jacinto shipped exorbitant amounts of gold to banks in Europe.

And then, suddenly, Maribel discovered that she’s connected to this figure.

[Maribel]: And yes, he was the owner of everything and… and Barrick Gold’s land.

[Mónica]: Here we need to explain this matter of last names, because if you recall, Maribel isn’t a Rosario. Her maternal last name is Amparo.

According to Maribel, that’s because her great-grandmother changed Maribel’s grandfather’s last name — Octaviano Amparo — to protect him from the alleged persecution the Rosarios suffered during the Trujillo dictatorship.

But what was clear to Maribel at that moment was that she was descended from Jacinto Rosario, regardless of whether that relationship had been hidden over time. And since Jacinto was the owner of that land, his family, then, could claim it.

And that was when Maribel remembered that phrase her grandfather would say, that one about being millionaires in land. And now convinced that her family was owed money, she decided to get a lawyer.

An acquaintance who went to the same church as Maribel in Santo Domingo told her that he knew one.

[Maribel]: We told him that we didn’t have any money because my family is very poor, here in Cotuí.

[Mónica]: But her friend told her that he could do the first consultation for free. So Maribel agreed.

The lawyer’s name was Johnny Portorreal Reyes. He was about 60 years old at the time, in 2011. They met at Maribel’s house.

[Maribel]: I called a few of my aunts and uncles and cousins and they came to my house. We had the meeting with Portorreal in my family’s patio. And that was where we spoke with him.

[Mónica]: They agreed that Portorreal could do the first consultation for free for the residents of the town. They just had to pay for his travel between Santo Domingo and Cotuí.

In late 2011, Maribel brought Portorreal to Cotuí for the first time.

[Maribel]: He came here with his son and two other people who were traveling with him, for security. And here was where we started to… to introduce him to the family.

[Mónica]: It was a small gathering of about ten people. All of them related. They sat down to speak with Portorreal in Maribel’s grandmother’s house, the small wooden house where she grew up.

[Maribel]: At that time I had my uncle Leoncio, Leoncio Fabián Rosario. He was alive and he didn’t believe in lawyers because many had come and had taken advantage of him. They take your money and they never did anything.

[Mónica]: Maribel’s uncle had had bad experiences with lawyers trying to resolve other issues.

But after a few meetings in Cotuí, Portorreal told them that he could claim compensation for the land where the mine sits.

And despite their initial lack of trust, Maribel remembers what her uncle Leoncio told her:

[Maribel]: “My niece, I… we don’t believe in lawyers. But if you brought this man, this lawyer, then we’re going to believe.” And that was when they accepted doctor Portorreal.

[Mónica]: It was an agreement. Portorreal would keep thirty percent of what they collected in compensation for the land.

The Rosarios battle for their land began.

At that time, there were only a few heirs. Portorreal started…

[Maribel]: With about ten people, including me, who were the first people to hire him.

[Mónica]: From the start, their strategy was for the group to grow. They didn’t know how many descendants Jacinto Rosario had, but Portorreal wanted to represent all of them

So Maribel decided to look for other descendants. It was no simple task. They needed to reconstruct the family tree as she had with her own family.

And so she got started: meeting with neighbors in the area, listening to family stories, and trying to follow the clues in the family tree.

[Maribel]: I sat here under the little mango tree, here with the older people in my community. We… we brought a typewriter and started writing, bam, bam, while they gave all their… all their versions.

[Mónica]: In other words, stories about who was related to whom in the town. Then they started spreading out.

[Maribel]: We started looking for… for heirs in every corner of Cotuí. And then we moved on to other towns.

[Mónica]: Maribel had to look after her two young children and her beauty parlor in Santo Domingo, but she was spending more and more time in the countryside.

[Maribel]: We had to look for Jacinto’s children’s birth certificates. We had to go to the church in Cotuí and things like that. They had to look for the acciones de peso.

[Mónica]: Acciones de peso, in other words, old property titles, from the 19th century filed away in the yellowing records of dusty government offices. It was a lot of work, and Maribel was just a volunteer. But her work was paying off. Well, they hadn’t won anything in the lawsuit, but what was happening was that the heirs…

[Maribel]: Started multiplying because I was having meetings here and a lot of people came.

[Mónica]: Portorreal traveled to Cotuí almost every week, usually on Sundays.

[Maribel]: So, starting on Friday people were going, “The lawyer comes on Sunday.” And by Sunday everyone was sitting there.

[Mónica]: Portorreal’s arrival was a grand event. It was like that for more than a year. The Rosarios started sending their documents, and together, they put together their family’s genealogy. Maribel says she showed Portorreal that the property titles, the ones called acciones de peso, belonged to Jacinto’s descendants. That ended up convincing Portorreal to take the Rosarios’ case.

So with that information, he started two lawsuits: one to remove Barrick Gold from their land and another for damages and harms against the company and the government. In total, Portorreal was asking for more than $12 million for the Rosario descendants. And that’s because we’re talking that after the initial lawsuit…

[Maribel]: People started coming and coming and coming. There were about 8,000 people, a little more than 8,300.

[Mónica]: More than 8,300 people in 2013. Because, of course, the rumor of the Rosario family fortune spread with incredible speed. Rosarios telling Rosarios, and them telling others. In record time, an immense and very strong network was formed.

Portorreal didn’t just take on the fight to recover the land, he also joined the community’s claim for the environmental damage the mine had caused. And that’s because even before the arrival of Barrick Gold, there were reports that the mind had left toxic substances like mercury and asbestos that ended up in the soil and the rivers.

[Maribel]: Here I have family who… who… who have died from contamination, cyanide, and all that. The rivers… the… the… they’ve all died.

[Mónica]: Johnny Portorreal organized protests over the environmental damage. And at the same time, he became the spokesman for the family. For its part, Barrick Gold has denied that its operation causes environmental damage.

In any case, Portorreal’s legal maneuvers were for the lands, not for environmental damages, and in the end, the suit didn’t move forward. In 2017, the provincial Lands Court rejected one of Portorreal’s lawsuits because Jacinto Rosario’s property titles, which in Portorreal’s strategy would prove that the Rosario family was the original owner of the mine, were insufficient and had expired. In 2019, the court rejected the other lawsuit saying that the lawyer hadn’t been able to prove that there was a connection.

Throughout this process, Portorreal had amassed a gigantic archive: birth certificates, marriage certificates, death certificates of thousands of Dominicans with one thing in common. The Rosario surname. In a certain sense, he had formed a family. A family tree that the Rosarios themselves didn’t have. Maybe this explains why, despite the setbacks in the courts, he continued being the lawyer for the great Rosario family.

And little by little, his argument started to change. He stopped concentrating so much on the lawsuit for the land and started telling the Rosarios that there was an inheritance guarded in European banks. It’s not clear how Portorreal knew that such inheritance existed. We realized that when we spoke with more than 15 of his clients. According to what they told us, Portorreal started thinking about the inheritance, in 2015. They told us that there was a rumor that Jacinto had sent bars of gold to a bank in Europe.

What they heard from Portorreal is that he was going to visit at least ten banks in Spain and Switzerland to ask in person if there were accounts in Jacinto Rosario and his closest relative’s name. If the answer was yes, he would ask the banks to send the money. Portorreal told the heirs that he could get that fortune.

[Daniel]: After the break, an inheritance turns into an obsession for thousands of Dominicans.

We’ll be right back.

[Throughline]: The world is a complicated place, but knowing the past can help us understand it better. Throughline is NPR’s new history podcast, each week we delve into the forgotten moments and stories that have shaped our world. Throughline, history as you’ve never heard

[Code Switch]: Whether it’s the athlete protests, the Muslim travel ban, gun violence, school reform, or just the music that’s giving you life right now. Race is the subtext to so much of the American story. And on NPR’s Code Switch, we make that subject, text. Listen on Wednesdays and subscribe.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, we visited the Dominican town of Cotuí, where some residents are claiming the land just outside of the town where there is a mine. And not just any mine. It’s one of the biggest gold mines in the world

The story goes like this. The people making the claim say they’re descendants of Jacinto Rosario, the supposed owner of the mine during the first half of the 19th century. And for that reason, they argued that they have the right to the land where Barrick Gold, the gold mining company, now operates. Or at least some compensation.

The lawyer Johnny Portorreal took on the Rosarios’ case and brought it to Dominican courts. They lost the lawsuit, but not long after, Portorreal started talking about an inheritance that would make the Rosarios one of the richest families in the country. Jacinto Rosario had supposedly deposited his gold in several banks in Europe. Portorreal offered to get that inheritance.

Mónica Cordero continues the story.

[Mónica]: Maribel Valoy Amparo started hearing about money being kept in European banks in 2015, almost four years after having contacted Portorreal. It was one day when she went to the lawyer’s office.

[Maribel]: Yes, that’s how it happened. All of a sudden, one day I went and they were already talking about the money that was internationally… that belonged to our ancestors.

[Mónica]: The idea was that Portorreal was going to recruit as many descendants of Jacinto Rosario as he could. Those eight thousand he already had weren’t enough. He wanted more. So he had several volunteers who coordinated the search for and recruitment of the heirs. Among them were Maribel and this other man…

[José Cepeda]: My name is José del Carmen Cepeda.

[Mónica]: José’s last name isn’t Rosario, but his wife’s is. He’s a vegetable seller. He lives in Maimón, a town very close to Cotuí.

[José]: He was going around getting signatures because there was a rumor that the Rosarios had an inheritance. He even came to my house. Uh, we met right there, near the mine.

[Mónica]: Portorreal recruited him very quickly.

[José]: He asked me to accompany him, to go with him to where the other Rosarios lived, since I was someone who knew the area.

[Mónica]: And of course, the promise of a million-dollar inheritance attracted a lot of people.

[José]: Johnny Portorreal said himself on one occasion that each heir would get more than 11 billion Dominican pesos.

[Mónica]: Which in 2015 would equal about 240 million dollars a person. 240 million dollars. Imagine it. Portorreal made the same deal with everyone: he would get thirty percent of the inheritance, and they would pay him as soon as the money arrived. Meanwhile, Portorreal continued saying that he didn’t charge anything for pursuing the case.

But that didn’t mean that the heirs didn’t have to give Portorreal money. On the contrary, there were several legal “expenses” that, for people like Maribel and José who were barely getting by, amounted to a lot of money.

Maribel worked directly with the documents at the office and she was well aware of the additional services each person had to pay for. She saw the Rosarios were handing over money bit by bit. A little here, a little there. It all started with the contingency fee. That is the term Johnny Portorreal used to refer to his contract with his clients.

[Maribel]: It’s a contract that the lawyer makes with every heir. Previously he charged 1,500. Then he raised it to 3,500. He kept raising it.

[Mónica]: That’s in Dominican pesos. In other words, between 40 and 85 dollars per contract, at the exchange rate of the time. On top of that, the contract had to be notarized, they had to put a seal on it. That also cost money. Then there was the PIN, a personal identification number. If you look at it, it’s a little piece of paper with a QR, those codes you scan with your phone, that supposedly had the name of their heir and their id number.

[Maribel]: It’s something that has the person’s name and their ID number which costs 500 pesos.

[Mónica]: About 12 dollars. According to Portorreal, the PIN would be used to access the bank account where the heir would receive their part of the inheritance.

And there was more.

[Maribel]: And there were also the two bonds, one with the right… ugh, there are so many things. Five hundred for each bond. And there was also a cumulative of 1000 for each document.

[Mónica]: The bonds served to finance the search for the inheritance. The cumulative was a document that the coordinators had to pay each time they registered before Portorreal the number of Rosarios they had recruited. There was also the rectification, which cost another 12 dollars and was paid to certify the name of the person included in the contract.

And the sworn declaration, to replace a relative’s lost death certificate, also cost money. They were documents with vaguely legal names, without much clarity about their purpose, but what was certain was the cost.

Between one thing and another, the potential heirs ended up paying between 70 and 140 dollars for their part of the inheritance. And to put this in context the minimum monthly salary in the Dominican Republic at the time was a little more than 200 dollars. Maribel could see the sacrifice her own family in Cotuí was making to pay. Because it wasn’t just what they were paying Portorreal, but the cost of travel and the time they were investing.

[Maribel]: A lot of them sold any animal, any little hen. They would do anything to go there, to travel there and get their documents. Going hungry.

[Mónica]: But despite the costs, Rosarios from all over the country and across the Dominican diaspora continued joining the project. At one point, she put her beauty parlor on hold to be Portorreal’s coordinator and recruit heirs. She would go from time to time to the Law Center, the lawyer’s office. It’s in a working-class neighborhood in Santo Domingo and it’s surrounded by outdoor mechanic workshops and street vendors.

[Maribel]: And they assembled in the street in front of the office which was full of heirs so they could be seen. And that was… I got there in the morning and it was night, and those people were going through hardship. It would rain and they would get wet in the street, they would get wet to get those documents.

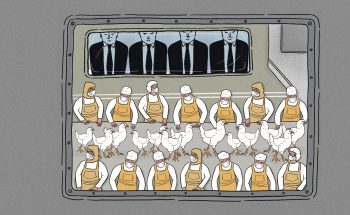

[Mónica]: Day and night, rain or shine, outside of the Law Center there were always lines of people who were going to give Portorreal’s team documents and pay for whatever may be. And that’s because Portorreal had organized a small army of people with a single function: to identify and recruit all of the Rosario descendants they could. All of the ones who were willing to join the search for the inheritance.

And the Rosarios’ cause was becoming more and more well-known. José Cepeda told us that when people found out that he represented that search…

[José]: A lot of families came to my house so I could represent them.

[Mónica]: It’s estimated that by the summer of 2018 there were around 140 coordinators.

Each one was in charge of looking for more heirs and keeping them informed of the news the lawyer was giving, with the promise that they would receive ten percent of the inheritance when it was paid out.

[Maribel]: There are coordinators who coordinate up to a thousand people. A lot of them have 500, 200, 300. So, any message was passed to the coordinators so they could pass it onto the heirs.

[Mónica]: José, for example, represented around 70 families, and he’s aware of the costs he’s incurred while working with Portorreal. He describes himself as an investor.

[José]: We made a small investment. You know that you have to pay for the PINs, the contracts, and trips to different parts of the country looking for documentation and people.

[Mónica]: But besides paying for his own expenses, sometimes he’s helped out heirs financially so they can join the search for Jacinto Rosario’s money.

[José]: Because the families are too poor and I would tell them, “Alright, I’m going to pay for everything you need for the documents, and I’ll charge you ten percent.”

[Mónica]: And he would make back that ten percent along with the money he had invested when the inheritance arrived.

[José]: And I have about 800,000 pesos invested in that… in that family.

[Mónica]: Around 13,600 dollars. A vegetable seller’s whole life savings.

As the group grew, Portorreal built a whole structure that was more formal and sophisticated and people believed. Aside from the coordinators, they also created various commissions: one for the Rosario family, an international commission, one for payment. It was a way of dividing tasks. The international commission, for example, organized the supposed heirs who lived outside of the country. They had contacted Dominicans in the United States and in Europe.

And the number of people they recruited grew exponentially. By 2019, almost eight years after having started, Portorreal had about 29,000 heirs. What started years earlier as a meeting in Maribel’s grandparents’ living room in Cotuí, would now fill Quisqueya Juan Marichal Stadium almost two times. That’s the second-largest baseball stadium in the Dominican Republic.

WhatsApp became a point of connection for people who considered themselves Jacinto Rosario’s heirs. By 2019, there were at least eight active WhatsApp groups that brought together Rosario heirs. In just one morning a thousand text and voice messages could be sent. There were the more formal ones, like this one.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Víctor Rosario]: A very good morning to you, Rosario family. Good morning foreign and local commissions. This is Víctor Rosario, alias “Mr. Chulito.” I’m recording this audio to clarify a few things and provide some information.

[Mónica]: But others were varied greetings and conversations.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Man]: Blessing from above, your cousin Julio Ángel del Rosario. May the peace of the Lord be with you.

[Man]: Family. Rosario family. Good evening. Good evening family.

[Woman]: A kiss and a hug for all my cousins. Happy New Year and Merry Christmas to… to the millionaire cousins, the new millionaire cousins.

[Mónica]: Rumors were also shared there that reinforced the idea that the inheritance would come.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Man]: Today there was an agreement and a contract was signed with the president… the owner of Barrick Gold. And they agreed, that contract they made was so the money that Barrick Gold pays to the government will be paid to us.

[Woman]: I was a witness. I was the first person who reviewed the documents and I have to tell you that the document certified by the Bank of Santander is real.

[Mónica]: It was also their means of communication with Portorreal. This is him:

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Johnny Portorreal Reyes]: We’re in the best conditions, never before seen nor dreamed of, for the Rosario family, if justice is done, to be one of the richest families in our country.

[Mónica]: And also via WhatsApp, his team kept people informed about Portorreal’s search, showing, or trying to show, that they were getting closer and closer to the money they all dreamed of. And sometimes there were audio recordings with the minute details of the lawyer’s weekly agenda.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Man]: Monday, Dr. Portorreal has a meeting with the man, the manager of the Reserve Bank of the Dominican Republic, the politician. Wednesday, the doctor, and even I am invited, I’m going to the congress. The attorney will speak at the congress.

[Mónica]: Portorreal used WhatsApp to make announcements that would later activate all the groups. Like this, which he sent after one of his trips to Europe.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: And I’m here to inform you categorically that the deposit of… from various accounts in large amounts of money is underway.

[Mónica]: Messages like that came every once in a while.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: What you want to hear is that the payment is ready and that there is… that all of the given conditions are met. We’re administering the payment today.

[Mónica]: The account transfer from a bank in Europe to a local bank in the Dominican Republic, Portorreal says, is going to take place that very day. Of course, there are no details. Portorreal didn’t talk about the amount, for example, but every time he sent one of those messages, the heirs got excited

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Heir 1]: They paid the attorney! They paid the attorney! And now we’re going in the name of Jesus. Yes!

[Heir 2]: The banks have the cash in their vault for the people who are going to withdraw the money.

[Heir 3]: I’m happy and pleased, the doctor called me and told me that the money will be paid out tomorrow. Now you know, cousins!

[Heir 4]: The topic I must discuss today is when I get the inheritance, what will I do.

[Mónica]: And they even celebrated the money’s arrival with songs.

(SOUNDBITE OF“SOMOS MILLONARIOS” BY ALFA FT ARCANGEL Y MAKR B)

[Voice]: Somos millonarios! Somos millonarios!

[Mónica]: But the money never arrived.

Jacinto Rosario’s heirs have invested a lot in the idea of this money. Perhaps too much to stop believing in it.

Meanwhile, Portorreal was constantly traveling to Europe: six times between 2016 and 2019.

He insisted that the trips were to meet with heirs abroad, with bankers, and authorities. And he used his communication on WhatsApp to give the impression that he was serious. Before leaving the country, he sent audio recordings and videos to the WhatsApp groups. This video, for example, is from 2018.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: Good morning Rosario family. Here are the documents I’ll be taking to Europe tomorrow, visiting various banks.

[Mónica]: You see him sitting at a table with a stack of papers and manila envelopes.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: There are documents here that are of indescribable value to the… the Rosario family specifically.

[Mónica]: He said that there in those envelopes was the evidence the European banks were asking for in order to make the transfers from Jacinto’s accounts to the Dominican Republic. And finally, the video ends with a warning.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: Every time I go we share the photo with the documents that we’re going to take. But then no one publishes it, no one… shares it, no one adds anything or researches it.

[Mónica]: It was a minor rebuke, because people didn’t share the photos. What Portorreal wanted was exposure.

Portorreal didn’t travel alone. A group of close advisers and family members went with him. On a trip in March of 2018, he sent one last message before getting on the plane

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: Our oath is that we’re going… but shame of our lives if we don’t come back with the money in hand. For the liberation of the Dominican Republic, carajo!

[Mónica]: You can’t hear it very clearly, but he says that if they don’t come with the money in hand, it’ll be a shame. And then he shouts with his entourage: “For the liberation of the Dominican Republic, carajo!”

After each trip, Portorreal kept on describing in greater and greater detail how the transactions were going to go:

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: There’s going to be a single payment and all the Rosarios, no matter who they are or when they arrived, will receive their portion. Uh, no family goes first or… exclusively.

The audits, the number of… of Rosarios and everyone, uh, will be duly certified and deposited jointly to… to the people on the list and in the payment directories.

[Mónica]: And it seems like he’s thought of everything. Here he’s explaining how the inheritance would be divvied out in family’s that had marriages between cousins.

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Portorreal]: If… if two Rosarios are married, uh, who come from different children, meaning, from… from cousins who are heirs, they will receive the inheritance from both sides.

That’s a simple mathematical equation. There’s no issue, but it does allow for people to receive in inheritance up to three times.

[Mónica]: These messages of Portorreal circulated on the WhatsApp chats in June of 2018.

Speaking with several Rosario heirs, we ran into the same argument again and again: the transfer was going to be so large that it would change the political balance of the country. The Rosarios would become one of the most powerful families in the country. And that would put an end to abuse and corruption. It was going to be revolutionary. It was almost messianic. And I’m not exaggerating. The religious theme was very pronounced in the search for the inheritance.

For example, Portorreal was constantly saying that God supported their cause. And when we asked 16 heirs who we spoke with if the inheritance was real, no one said no. They didn’t even consider the possibility. They assured us that they trusted that God would provide. And the inheritance was going to help change the country.

One of the people who accompanied Portorreal on his last trip to Europe in May of 2018 is Nelson Peña.

[Nelson Peña]: We went to Spain, Madrid, Burgos, and we also went to… to Switzerland.

[Mónica]: That trip lasted 45 days. Nelson’s last name isn’t Rosario. It’s Guzmán, a family that’s after another inheritance, the one left by don José de Guzmán, known as the baron of Atalaya.

Legend has it that the baron, who lived in the 17th century in the Dominican Republic, left an inheritance that is lost. Portorreal represents both groups of heirs. Nelson joined Portorreal’s group in 2018, and that same year he was given the opportunity to accompany him as his English-language translator.

[Nelson]: I got the chance and I didn’t… I didn’t think twice about it.

[Mónica]: Nelson had two jobs. He was a UPS driver in New York City and he also did deliveries for another company. He has four kids at home and one of them has autism. Being gone for so long would have consequences.

[Nelson]: I took a big risk when I went on that trip, but I knew I had to do it.

[Mónica]: Being part of the group that was going to get the inheritance was big, exciting, even revolutionary. Nelson didn’t want to miss it.

[Nelson]: I always had the idea that… that it was going to be historic. It wasn’t just about the money, but it was going to change the history of the Republic.

[Mónica]: And he dove in headfirst. He spent his savings and ended up paying for the trip with his mom’s credit card. In total, he spent 8,000 dollars. When the group arrived in Spain, a few members of the international commission were waiting for him.

[Nelson]: From the moment we got off the plane, Rosarios were there. And the way they treated us was incredible.

[Mónica]: They moved them around in Madrid. The members of the international commission were very attentive. Portorreal was paying for the trip with money from the Rosario family and investors. After that initial wonder at setting foot in Europe for the first time, Nelson realized that the trip wasn’t what he imagined.

[Nelson]: Well, I thought it was going to be different. I thought we were going to arrive in Spain, and… and they would recognize us as Rosarios and Guzmáns at the banks, but that’s not what happened.

[Mónica]: And that’s because Nelson doesn’t even remember visiting a bank in Spain. Portorreal was in control of the trip’s itinerary, and in Madrid, they had several meetings with Rosario and Guzmán groups and they looked for historical documents, but they didn’t do much more than that. Then they traveled to Switzerland.

[Nelson]: We came to deliver a Guzmán family document that was missing, and also a…. I think there was a document for the Rosarios too, and they brought it to the Credit Suisse bank.

[Mónica]: Of the 15 people that went to Switzerland, only four went to the bank. Nelson wasn’t one of them. He waited at a cafe with the others. But the supposed meeting at Credit Suisse…

[Nelson]: It didn’t… it didn’t last long. It was like 20 minutes.

[Mónica]: As far as Nelson is aware, there was no transfer of money to the families at that time. At least he didn’t receive any. It wasn’t clear to him what they had accomplished on the journey either.

The return home was difficult. He had lost his two jobs because he was gone for so long.

[Nelson]: Everything. I left behind everything. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I didn’t one to talk to my wife, my sons, my daughters. I didn’t want to do anything. My mind was fixed on an end. I don’t know if that… if that is selfish, I think, but that’s the way I am. I wanted to make it to an end, and I left everything behind.

[Mónica]: He had believed in the inheritance, in the possibility of a treasure that would change his life, his country. And beyond a 20-minute meeting, the money didn’t seem to be any closer.

For people like Nelson who lost two jobs because he was on the trail of the inheritance, the consequences of not seeing that money were enormous. In 2019, after his trip, he lost his house in New Jersey. He and his family went a month without their own home. They spent that time…

[Nelson]: In my brother-in-law’s basement, and at another point in a hotel. Those were the darkest days for me. Thir… thirty days.

[Mónica]: Eventually they were able to move into a new house, thanks to an assistance program. But, aside from that, the search for the inheritance had other consequences.

Nelson had borrowed money from his mom, and when he came home from his trip to Spain and Switzerland, the family expected him to bring a lot of money back. But he had to tell them the truth…

[Nelson]: I didn’t have the inheritance. They had to wait.

[Mónica]: The family waited. For a while. Then they confronted him.

[Nelson]: Why on Earth did you go to Europe? Why did you use my mom’s card?

[Mónica]: One of his sisters even told him…

[Nelson]: That I can’t go to my mom’s funeral. That’s what she said.

[Mónica]: Why?

[Nelson]: Because I killed her. And she’s still alive. It’s unbelievable… what the prospect of money does.

[Mónica]: While we were investigating this story, I heard many stories like Nelson’s, stories about taking on debt, families fighting, savings lost in the search for Jacinto Rosario’s gold.

Maribel ended up losing her beauty parlor because she was Portorreal’s coordinator. José del Carmen Cepeda is still waiting to recover the thousands of dollars he’s invested in searching for the inheritance. And so many more.

It had been nine years since the search started, but Portorreal hadn’t delivered anything.

[Daniel]: In the next episode, the battle between Portorreal and an heir who would become his greatest enemy

(ARCHIVAL SOUNDBITE)

[Anibelca Rosario]: So this man motivates, forces, plays, threatens his followers to open a savings account in the Reserve Bank of The Dominican Republic. And the Reserve Bank knows that is a con

[Johnny Portorreal]: She’s accusing me of being a thief. And she’s accusing me of being a conman. And she has accused me in the whole country. Who are conning the Rosarios? Extorters! Discreditors!

[Daniel]: Mónica Cordero is an investigative journalist. She lives in New York and works with Univision’s Politics digital team. She co-produced this story with Luis Trelles. Luis lives in San Juan Puerto Rico and he’s an editor at Futuro Media.

We’d like to give a very special thank you to Joe Nocera. We’d also like to thank Frank Báez, Rita Indiana, Andrea Bavestrello, Juan Carlos González Díaz, and Alicia Ortega for their help with this story.

This story was edited by Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas, Victoria Estrada, and me. Andrea López Cruzado did the fact-checking. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Jorge Caraballo, Aneris Casassus, Xochitl Fabián, Rémy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Desirée Yépez.

Fernanda Guzmán is our editorial intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.