Transcript: A Tropical Fog

Share:

Daniel Alacón: Hi, I’m Daniel Alarcón, Radio Ambulante’s Executive Producer.

Before we start, I’d like to thank our sponsors.

First, Mail Chimp. Over seven million people and businesses around the world use MailChimp to send email and newsletters. If you receive Radio Ambulante’s emails, well, you’ve received an email from Mailchimp. It’s a service that has worked great for us. To learn more visit Mailchimp.com.

And Ting. This is four our listeners in the United States. Ting is a cellphone company that uses Sprint’s signal, but with their own fees. 98% of new users save money when they switch to Ting. Visit ambulante.ting.com, to get $25 towards your first cellphone with Ting.

Now, back to the show.

Welcome to Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Last month in San Francisco, California, we presented our live show, Outsiders. The idea was to tell stories about people who don’t fit in. One of the first stories we picked for the show was this one, by Deldep Medina.

–

Deldep Medina: To tell this story, I need help from my mom…

Delfina Bernal: I am Delfina Bernal, a Colombian artist, naturalized in the United States. I’ve lived in California since 1981. July of ‘81.

Deldep Medina: I came to San Francisco with her and my stepfather, David. He was American and a little bit of a hippie. I was just about to turn 8 years old. We came from Barranquilla, Colombia, a hot Caribbean city. Until this moment, my childhood had consisted of jumping around from city to city, country to country. We came to San Francisco trying to create the stability I hadn’t known yet.

I remember that, although it was supposedly summer, it was really cold and there was a lot of fog. I remember that in the taxi going to the house, I fell asleep, and I almost fell over when the car went uphill. That’ how steep the streets were. The first impression I had of San Francisco was that it seemed like an unstable city. And my mom…

Delfina Bernal: I was disoriented, it was like I was out of place. Here was this tiny city, it was cold all the time, and I didn’t know anyone either. I didn’t like anything. (laughs)

Deldep Medina: And well…Me, at eight, I felt the same way.

We came to live in the Castro.

And despite how grey the rest of the city was, The Castro looked more like Barranquilla. In the early 80’s the neighborhood was a party, with lots of movement, with lots of commotion. There were clubs where people danced until dawn, and an almost tropical feel. I liked the neighborhood. I liked that the neighbors always said nice things to me. Harmless flirty compliments. What a beautiful girl. How nicely dressed.

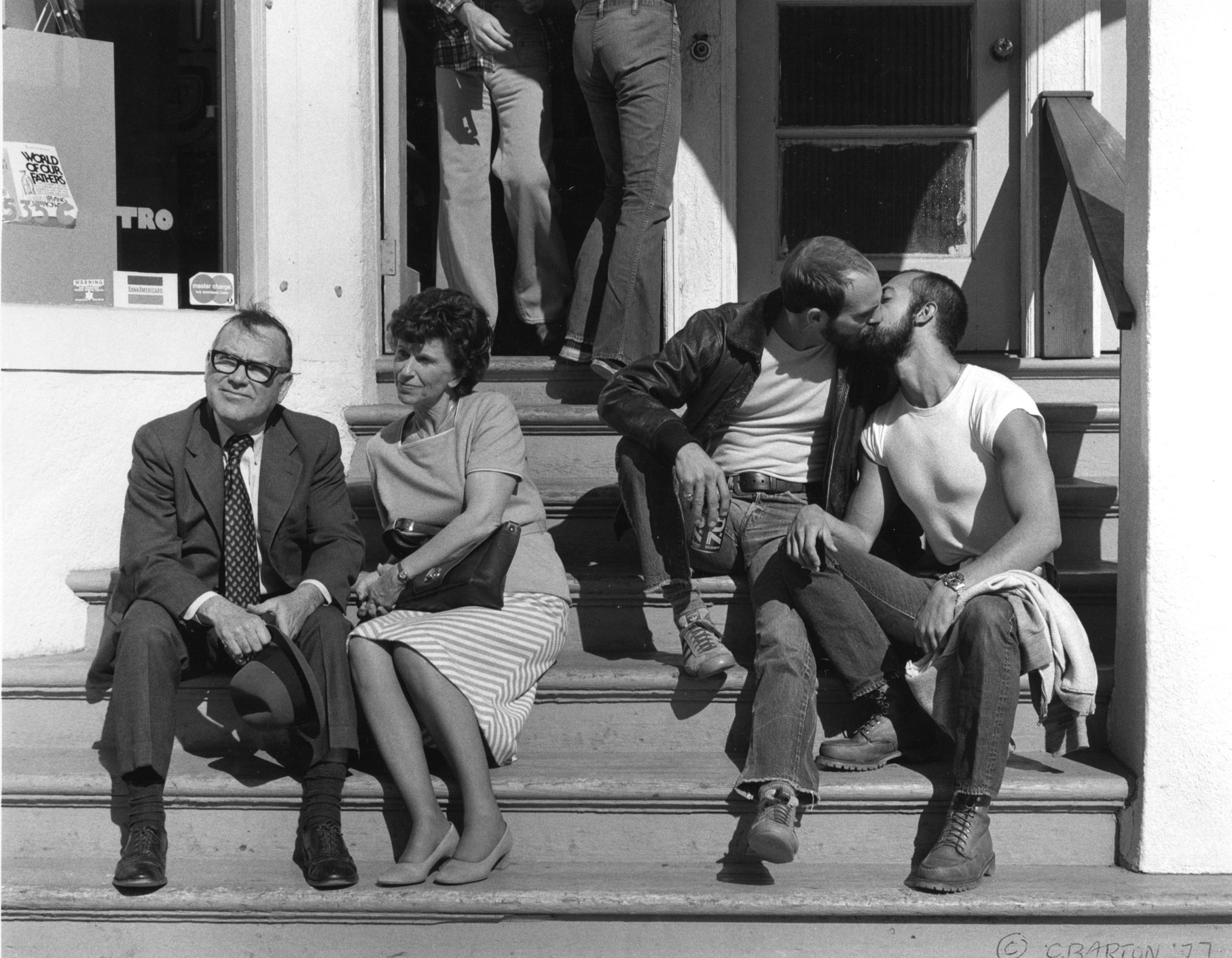

But I didn’t like one thing: there weren’t many kids there, and I didn’t have anyone to play with. There weren’t any families around, or barely any. Most of my neighbors were young men, pretty much all of them really. Handsome young guys, neat and well-dressed. And they all dressed the same, like they wore uniforms.

Delfina Bernal: The look of the moment was…very tight jeans, very fitted, young men, with their hair very short, and they looked healthy, among other things. Most of them were very handsome (laughs) It’s the truth. The women though were ugly. I thought those women were so ugly…[laughs]

Deldep Medina: My mom…well she’s always been very…direct

But part of what she says is true. The men were beautiful. Most of them looked alike. Castro Clones, they called them. With their short hair and well-groomed mustaches. All muscular. With their different colored shirts, neat and clean. They were, like my mom said, beautiful and impeccable.

That’s why, when all of my beautiful, fashionable neighbors started getting sick, it was shocking.

That year we arrived, we moved three times within the Castro. I was used to packing up and living with suitcases instead of furniture. We didn’t have much money, and my life began feeling like one move after another. Until we arrived at number 734 Castro, at the intersection with 17th street.

We were in the very center of a neighborhood famous worldwide for its spirit of sexual liberation. At school, when they found out where we lived, they asked me if my stepfather was gay, and I, completely oblivious, answered that I didn’t know, that I would find out.

My family, the ones who stayed in Colombia, with their prejudices, worried a lot about us living here.

Delfina Bernal: “Oh, you all are in it! You’re living there in the thick of it all the time!” But I said, “what are you talking about? What ruckus? “Yes, everyone is gay in San Francisco, and you’re all in the middle of it!”

Deldep Medina: This thing that the prejudiced called ruckus, we liked. It was a euphemism, of course. With ruckus my aunt meant the liberal atmosphere of the neighborhood. She imagined men fondling each other and making out on the corners. But in reality they were very discreet and I never saw much of this.

I felt good there. My neighbors, especially, were sweet. They were a gay couple. One was tall, and he worked in a bank. The other one, shorter, sold paintings in a store. Careful and refined, they had parties all the time and I listened through the wooden walls that separated our houses.

We weren’t intimate friends, but we got along well. And two times when my mom lost her keys, they let her go through their house and jump the fence. And she was fascinated by what she saw, something very different from the chaos that reigned in our house.

Delfina Bernal: I was embarrassed… the shorter one already had dinner prepared, the table was set, with carefully placed artichokes. And he came in to our garden to steal flowers to make is bouquets.

Deldep Medina: I grew up understanding what was still totally shocking for the rest of the country at this time: that gay people were normal. Like everyone, they got up every day and went to work…

Delfina Bernal: During the week, he was dressed up in a suit and everything[laughs], with a tie…And the other one worked in something else, and he dressed normal. And on the weekends, they dressed in leather both of them, and they went out with their leather pants [laughs]

Deldep Medina: To have a good time, I imagined, in the bars and clubs throughout the neighborhood. But it was also a neighborhood of small stores, flower shops and bookstores that I visited often. This was where I found comics from the 40’s, bought dried flowers and used books with my few cents.

The same month that we arrived in the United States, July of 1981, a notice appeared for the first time in the press about an illness that didn’t yet have a name. This article, from the New York Times.

“Rare Cancer Seen in Homosexuals”

It says, “cause for outbreak: unknown.”

And the epicenter of this new plague was our neighborhood.

When I turned 10 my parents bought a camera for me. A Kodak 110.

From then on, I brought it everywhere. It was 1983. And the neighborhood was changing. I went all over the city by myself. And I took pictures of the streets. Of buildings, mostly. I loved those Victorian houses that had survived the 1906 earthquake. I preferred taking pictures without people. I don’t know why, but now I see it as if it had been a premonition.

When was the first time you heard the word AIDS?

Delfina Bernal: Well, AIDS. I think it was when we went to the pharmacy.

Deldep Medina: My mom is referring to the neighborhood’s corner pharmacy. One day they put up some posters in the window.

Delfina Bernal: Color photocopies…or something like that…with these spots that had appeared on people’s skin. So, they were asking if people knew what this was.

Deldep Medina: No one could explain it, but now it wasn’t possible to deny that our neighbors were sick. The fashionable men that always walked around with tight short-sleeve shirts, without caring about the weather…these same men who always showed off their amazing bodies…now they walked around in long sleeved shirts…and later in sweaters with turtlenecks.

This was how you knew they were sick. They changed how they dressed.

And our neighbors did too.

Soon it wasn’t the tropical, happy neighborhood anymore, the one we had come to only two years before.

One day, the family of one of the neighbors came. They were normal, serious people. They came in to take the sick person’s things. I don’t remember which one it was, the tall one or the short one, the banker or the painter, that was dying. Perhaps both. I just remember that some family members came, and they took their things.

I never saw them again. And they weren’t the only ones. Pretty much everyone left, in one way or another. One after another after another. Their families came, in some cases the same families who had rejected them for being gay, and took them. Returning to the houses they had escaped from…many were not doing well. Half insane. In the last stages of AIDS many became incomprehensible, bitter, difficult. And every time a neighbor was taken away, my world became a little more sad. Me, at 10 years old, couldn’t help noticing. There was less sweetness, less humor, less life.

For me, it was as if the lights went out in my neighborhood, house by house, street by street.

Daniel Alarcón: Deldelp Medina is an entrepreneur and the founder of Avion Ventures in San Francisco, California..

This story was edited by me, Daniel Alarcón, and produced by Martina Castro, for our live show in San Francisco, California, on November 2, 2014. Special thanks to the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and our sponsors.

The Radio Ambulante team includes Silvia Viñas, Camila Segura, Claire Mullen, David Pastor, Diana Buendía, and Constanza Gallardo. Carolina Guerrero is our Executive Director. Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. To hear more, visit our website, radioambulante. org. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.