Family Album– Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Sometime in October of 2019, in Colombia, Camilo Rozo was moving to a different house, and as he was packing, he opened one of those forgotten drawers we all have. And then he found the photo album. Or rather, he found it again. It had been there, abandoned, for eleven years.

[Camilo Rozo]: At that moment, when I saw it again, I can tell you that I felt like a kick on the stomach.

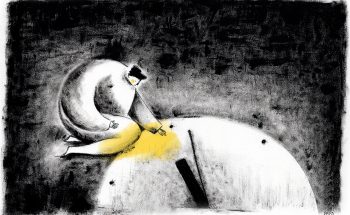

[Daniel]: It’s the typical album with metal rings on the spine and a hard cover.

[Camilo]: The cover picture is a foreign girl; it’s . . . it’s like a girl in a scarf. It’s a sticky album with one of those transparent adhesive pages on top. And the album was in pretty bad shape.

[Daniel]: As if, at some point, it had gotten wet. But the photos were intact. On the first page, in black and white, a couple was getting married in a church. Then there were color photos of family scenes that included children: baptisms, birthdays, games in a park, country walks, a swimming pool.

Seeing those images, those faces, he felt a mixture of guilt and sadness.

[Camilo]: And my eyes watered and I felt that, well, at that moment I was the worst human being.

[Daniel]: That album was not his, nor was it his family’s. It had fallen into his hands eleven years earlier in a work-related situation. Camilo is a photographer. And maybe that’s why, because of his job, he understands better than anyone what a photograph can mean.

[Camilo]: I was holding their memories—that is, this is my livelihood. Photographs are memories. If you’re a photographer, it’s precisely because you like to suspend moments in time, right? And keep them and treasure them and relive them later.

[Daniel]: But there was something else causing all the guilt . . .

[Camilo]: I had kept the family album belonging to other people who have a relative who had disappeared. I mean, I couldn’t forgive myself and it hit me very hard. Then and there I swore to myself, I told myself, “That family has to show up. I have to do whatever needs to be done for them to show up.”

[Daniel]: David Trujillo and Camila Segura reported on this. Camila picks up the story.

[Camila Segura]: Camilo has been taking all kinds of photos for over 30 years—portraits of politicians, athletes, writers. He has done photojournalism and has portrayed the different problems of Colombia in various ways.

It was because of that job that he wound up keeping the album. In 2008, he was contacted by a foundation called País Libre. They promoted policies to prevent kidnapping and help families who were victims of this crime. They sought justice, truth and reparation, and also offered psychological support and visibility for their cases.

[Camilo]: País Libre ended up contacting me through their press office and asked me to submit a proposal for artistic photographs that would illustrate, in some sensitive way, the drama of kidnapping in the country at that time.

[Camila]: Camilo was interested in the project, particularly because he had survived a kidnapping with his dad, and he understood well how painful and stressing it could be. So, he sent them a proposal, thinking he would work with families that were part of the Foundation.

[Camilo]: What I imagined was that I would choose a group photo of the family including the loved one, and then I would replicate it in that same space, highlighting the absence of that person. Something to show the passage of time and then absence, through photography.

[Camila]: País Libre liked the idea. They told him they would be in touch soon to follow up on the process. In the meantime, they sent him a photo album of one of the families so he could get started working and choose the first image. They gave him no further information at the time. The idea was that later on, they would give him more albums and get him in touch with the different families.

But months passed and the Foundation never completed the project. Camilo waited for instructions to return the album, but no one said anything to him. He had other things on his plate at the time—traveling for work and new projects, so he ignored the subject.

[Camilo]: I can say that as of July/August of 2008, I completely forgot I had that album, and I never left it in a visible place where I would remember it.

[Camila]: We’ve already told how he found it again, and all the emotions he felt. So he set out to search. The first thing he did was take his cell phone and check his email. Surely the messages that he sent to País Libre would be there.

And they were. The oldest he found was from March 2008. The one where he sent his proposal.

[Camilo]: The dimensions and such, even a quote for it. And they never answered.

[Camila]: Or at least, they never answered that specific message. What he did see was that the person he wrote to was called Javier Velandia, who at the time he was the Foundation’s press officer. Camilo remembers very well that he was the one who gave him the album and that they probably coordinated this over the phone. He recalled that in those days . . .

[Camilo]: I went to the office, he handed it to me in a manila envelope. And I took it home, waiting for the rest of the instructions I had given in my emails, but País Libre never responded on how to proceed.

[Camila]: He also found an email in which he told the Foundation that they should summon the family by the end of April to take the first picture. But he found no reply to that message, either.

No way to call Javier because he didn’t have his number. Also, País Libre had closed in 2017, and that institution’s email address no longer worked. So he couldn’t contact him that way, either.

All he found was a response that Javier had sent him in July 2008.

[Camilo]: I’m going to read it to you. It says: “Camilo. Once again, sorry for the delay. We hope that in the next three weeks we will complete the list of the thirty people authorized to be part of the campaign. However, due to internal issues and the national situation, we have not found the time necessary to bring everyone together. I understand the time you need to do a good job,” and so on. And there we said goodbye, and this is July 2008. That’s when they disappeared.

[Camila]: They never continued the project, didn’t contact him again, and didn’t ask him to return the album.

It seemed that emails were not going to be the way to find the family, so Camilo returned to what was closest, to what he had at hand.

[Camilo]: Go back and look at the album in detail, see if there was any sign there that would guide me, and the sign was always one single thing . . .

[Camila]: One photo in particular, of a girl who seemed to be about seven or eight years old.

[Camilo]: She appears in one of those typical school photos where you’re holding a pencil and you’re looking at the desk where they put the name of the school, the grade, the year. And it shows the beautiful blonde girl at school, smiling, writing. Her young classmates are behind her.

[Camila]: On the desk where she’s writing is a plaque with the information of the school.

[Camilo]: It read: Concentración Vianey. JM Bogotá. Grado 2A, 1983. That was the only clue I had.

[Camila]: He searched online for information about that school. He found out that the place still existed, in the southeast area of Bogotá, but now it had different name. Then he found a phone number.

[Camilo]: So, I called the school. The secretary answered and I said, “How are you, I’m so-and-so. I do such-and-such for a living, and I have this . . . this problem. I need you to help me.” And she said, “Look, I’m the wrong person because I’ve been working here “I don’t know, “six months, but call tomorrow and talk to so-and-so.”

[Camila]: But the person he spoke to the next day didn’t really know how to help him either. Everyone was willing to do something, but they told him it was very difficult to find a document, a list, any information.

[Camilo]: At that time, any record that might have existed physically—because in ‘83 everything was physical—had been discarded at some point, thrown away, burnt. It did not exist. So, it was impossible to go through the school.

[Camila]: Then it occurred to him that maybe social networks could be useful. So he decided to start a Twitter thread on November 5, 2019 . . .

[Camilo], “Friends, today I want to ask you for a huge and very special favor. I need you to help me find the family of a kidnapped person, so I can return a photo album that I’ve kept for eleven years, and that every so often keeps me awake at night.”

[Camila]: He tells the story, gives some details, and concludes saying:

[Camilo], “It really is something that torments me. Attached are several images, to increase the chances that someone will recognize them, and that way I can return what belongs to them.”

[Camila]: People got hooked on the story and it got close to four thousand responses.

[Camilo]: And that’s where the most beautiful surprise came, and it’s what people did, the tasks people took on themselves just to help me find this family.

[Camila]: Since Camilo had posted the picture of the girl at school, some people began suggesting ways to find the place.

[Camilo]: Someone sent me the satellite location and the coordinates and the full image of the school he had found on Google Street View.

[Camila]: Others suggested looking for a group of college graduates on Facebook. But it was just an elementary school, and Camilo had already tried that to no avail.

Then they suggested something else:

[Camilo], “Dude, that album is so old that for sure, if you remove the photos, you’ll find information behind the photos.” I had tried that too, but they’re under years of pressure, gravity and glue, so it was impossible to remove any of the pictures. And if I had, I would have ruined them. So, no.

[Camila]: Someone else sent him the same picture of the girl, but they had used an app to see how she would look slightly older. Maybe that way they could get a little closer to her current appearance.

[Camilo]: Beautiful things that honesetly moved me so much. Those demonstrations by people . . . they filled me with emotion. I appreciated each gesture and each expression from someone. The thing about the aged photograph seemed like a beautiful detail to me.

[Camila]: The closest clue was someone who sent a screenshot of a post they found on Facebook. It showed an identical photo, with the same information about the school and the date, but with another girl.

[Camilo]: So it was taken within minutes—a classmate of the girl who is the protagonist of our story. That’s when I felt that I was about to find it, that . . . that . . . that everything was coming together for us to get there.

[Camila]: Camilo examined the screenshot. The man who posted the photo had written, “My pretty little sister at age nine, just like her daughter.” He looked up that person on Facebook and wrote to them.

[Camilo]: I waited many days and I got so desperate that I got on their Facebook a lot. I searched and searched them, and I found the sister, that is, I found the girl in that photo. And I wrote to her inbox. But there’s also a problem with Facebook, that when a person you don’t follow sends you a message, years can go by without you seeing it.

[Camila]: And sure enough, at that time no one answered. But people kept tweeting him. They sent him more information, suggestions, and also contacts. Among them was the number of Javier Velandia, the director of communications at País Libre who had been the link with the Foundation. Camilo called him and told him everything. Javier was interested, he offered all the help he could provide, but there was a problem.

[Camilo]: He couldn’t remember the project, or the album, or the family. I sent him the pictures directly via WhatsApp and he said, “Brother, no matter how much I look at them, I can’t recognize any of the families we were meeting with at the time.”

[Camila]: Because of course, the people in the photos were much younger than when he may have met them.

Javier consulted with other people who had worked with him at the time, but since all this had happened eleven years back, the memories they had were confusing and there were no longer any documents with telephone numbers or addresses. So this didn’t work out either.

That year 2019 passed, and nothing happened. Camilo moved into his new home and went on vacation for a few weeks. When he returned to Bogotá in January 2020, he found a message from the woman he had contacted on Facebook, the one who had a photo very similar to that of the girl. But the same thing happened:

[Camilo]: She said she was very moved by my story, that she was indeed the person in the photo, but as is only natural, she doesn’t remember a classmate from 1983.

[Camila]: She told him that she had asked some of her friends from that time and they didn’t remember her, either. Another door was closing. But since he wrote the thread on Twitter, he had begun to hear from some of the media who were interested in the story.

[Camilo]: There were a couple of stations and a couple of those TV shows, kind of like tabloids, but I didn’t want my story to turn into that. I wanted them to help me find the family.

[Camila]: By then, Camilo had exhausted all options. If talking to the media was the only thing left to do, he had to do it. It was either that or not finding the owners of the album.

He began reconstructing everything that had happened, so he could tell the story to the media the right way. He checked the album again and looked for the País Libre emails, but this time he did it from his computer. And that bit of information is important because, as we mentioned earlier, the first time, he searched only his cell phone.

[Camilo]: In Gmail, when you search for “emails” on your phone you never get all the results. The search engine is terrible. I think that had something to do with it.

[Camila]: It had to do with his not finding a key document in all this, and now he did find it. It was attached to an email from Javier in which he talked about the photos and the project but didn’t mention the document.

[Camilo]: And attached was an Excel sheet with names, last names, and some landlines.

[Camila]: There were twelve people in all. The document had no further information, it didn’t even make clear who the people on the list were.

[Camilo]: And then I said, well this is the last thing I can do, and I started calling each of those numbers.

[Camila]: Several of them no longer existed; the phone didn’t even ring.

[Camilo]: In a couple of others, someone did pick up, but they were people who didn’t answer to the name that appeared there. Or they would tell me, “What a shame, I moved to this house just five years ago or eight years ago.”

[Camila]: And said they didn’t know the former tenants. That happened with eleven numbers on the list. Only the last one remained.

[Camilo]: The last number was Doña María Luz Velásquez, I dialed, she answers and I ask her, “Are you Doña María Luz Velásquez?” And she says, “Yes.”

[Camila]: Well, at least a ray of light. The person who answered was the same person who appeared on that list. Camilo took the next step.

[Camilo]: I said, “Doña María Luz, this is Camilo Rozo, I work for such-and-such media, I do such-and-such. Do you by any chance have a relative who was kidnapped or disappeared?” And she was quiet for a few seconds . . . she was quiet for a few seconds and she said, “Tell me more.” (Crying) And we were both silent and cried . . . at each end of the line. And I told her, I said, “I have a family album of yours that looks like this and that. The first picture is a photo of your wedding, there are some pictures of a beautiful little girl.” And she burst out crying, and so did I.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a pause.

[Daniel]: We’re back at Radio Ambulante. This is Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, Colombian photographer Camilo Rozo had done everything he could think of to find the family that owned the photo album. The last thing he did was call a list of phone numbers he discovered in an email that had gone unnoticed.

The last contact on the list, María Luz Velásquez, answered and told him that she did indeed have a missing relative.

[Camilo]: And she says to me, “Tell me more.” And I start to narrate things from the album to her, and she starts crying and sobbing, and I knew we had arrived.

[Daniel]: He had found the owner of the album. She confirmed it. Camilo quickly explained why he had kept the album and everything he had done to find her. He proposed that they meet, he wanted to deliver it to her personally. María Luz replied that she lived very far from where he was, and she couldn’t move from her house because she had to take care of her husband who was in a wheelchair and was awaiting urgent spinal surgery.

That mention of her husband surprised Camilo.

[Camilo]: Throughout my search, I always thought that the person missing from the family was her husband. And she said no, the missing person from my family is my daughter.

[Daniel]: The same girl who was in the photographs.

Camila Segura picks up the story.

[Camila]: Camilo didn’t want to ask her for details of what had happened to her daughter. It was not the time, especially on the phone.

[Camilo]: But I was completely upset. In other words, the story was taking a different turn from their drama . . . it’s . . . it’s . . . the drama is even worse.

[Camila]: They hung up and agreed that, depending on how the situation for Maria Luz’s husband progressed, they would decide where to meet and when. But the pandemic came and then the confinement and they had to postpone everything.

About six months passed, and in mid-2020, when some restrictions were lifted, Camilo couldn’t hold it any longer and made an appointment with María Luz.

On June 12, Camilo left his home in a taxi. He had wearing a mask, biosecurity suit, recording equipment. The address was confusing and Camilo was unfamiliar with the area.

[Camilo]: I’m lost again, hold on a second. Hold it, give me a second. No, come on, keep going a little bit farther, brother. I think we went too far, yeah. What a pity!

[Camila]: He was also nervous. He felt guilty for having forgotten the album so many years. Someone had taken their daughter from them, and he felt that he had taken the pictures from them, a tangible memory of the person who was no longer around.

That was why he had been so anxious to return the album. He couldn’t wait any longer carrying that guilt inside. And besides, who knew how long the pandemic would last. He wanted to see them and give them what belonged to them.

Germán Ladino, María Luz’s husband, ended up giving him directions by cell phone, and he arrived around three-thirty in the afternoon.

[Camilo]: Doña María was waiting for me in the . . . outside her house.

Doña María, how are you?

[María Luz Velásquez]: Very well, and what about you? Come in, come in.

[Camilo]: Thank you.

The house is a three-story house. It seems to have been built over the years.

[Camila]: They are the owners of the house and have rented out two rooms. María Luz ushered Camilo to the second floor. She lives there with her husband Germán.

[Camilo]: Are we going upstairs, to the next one?

[María Luz]: Yes sir, yes.

[Camilo]: They told me right away, the first thing she told me, my husband is in a wheelchair, they haven’t been able to do the surgery because of the pandemic.

And how is Don Germán? No news about the surgery, have they said anything, Dona Maria?

[María Luz]: Nothing. He’s horribly depressed.

[Camilo]: He’s a person who is suffering so much, there at . . . at home and in his wheelchair, with the confinement and other things.

[Camila]: Camilo didn’t give them the album right away . . .

[Camilo]: For no other reason than that I wanted them to trust me, so that . . . that we could talk about things before I recorded the moment.

[Camila]: He wanted to make a video of the delivery of the album and take some pictures of them. Not to publish them, but for himself, to record the moment.

They went on talking about things, about Germán’s surgery . . .

[María Luz]: They had already given him the go-ahead for exams, everything, everything was in place.

[Camila]: About their pet bird . . .

[Camilo]: The bird—is the bird silent, or did the bird die?

[María Luz]: He’s covered up for now.

[Camila]: About the things the cat eats . . .

[María Luz]: He eats tuna fish. He has a schedule when he asks for tuna.

[Camila]: After conversing for a while, Camilo asked them for permission to record the handover of the album. They accepted.

[Camilo]: I set up the phone on the tripod of the microphone I had brought to record them, so that it would be okay, so there would be a good memory of that. And I focused on them.

[Camila]: María Luz is sitting on the living room sofa and next to her is Germán, in the wheelchair. They both know what’s coming, and you can see the expectation and anguish on their faces. Camilo appears on camera for a few seconds, as he approaches and extends his arm to hand them the album. María Luz clenches her mouth, squints her eyes, receives the album. And Germán thanks him . . .

[Germán Ladino]: Thank you very much.

[Camila]: She asks Germán, “Do you remember?” And she shows him the cover. He grabs it but it seems that Maria Luz doesn’t want to let go of it so quickly. Then she gives up and passes it to him, without opening it. You can see her holding back her tears and putting her fist to her mouth. Germán looks at the cover, turns the album . . .

[Camilo]: And there comes a very moving moment. He tries to open it and tries to look at it, but he can’t. He doesn’t, he doesn’t make it. And he closes it, but tries to open it . . . but he can’t, he can’t take it anymore. He hands it to her. And she hugs it . . .

[Camila]: She hugs the album. She hugs it and puts her head on it. It gives the impression that she’s hugging a person and resting her head on the person’s shoulder. Then she opens it. Slowly. And she begins to look at every page. She pauses for a few seconds on each photo. Her hands are shaking and she is sobbing. She cries silently. She doesn’t say anything else, but as she turns each page, you van see how much she is impacted by each image, each trip to the past.

Germán doesn’t look at her. He stares in another direction.

[Camilo]: And he puts his hand on his . . . on his face and starts to cry.

[Camila]: He wipes his tears as she turns each page and examines each photo. At some point, Germán begins to look out the corner of his eye. He sees one of the pages, looks up, and then Camilo tells him . . .

[Camilo]: Don Germán you could look at it one photo at a time so that your heart can resist.

[Germán]: (chuckles).

[Camila]: Germán only lets out that little laugh that can be heard but doesn’t say any more. When María Luz finishes looking at all the photos, she closes the album and thanks Camilo.

[María Luz]: You have no idea how grateful we are. Because this, in other words . . . Oh, my album, my album!

[Camilo]: I apologize for all those years I kept it away.

[María Luz]: No, that was the Foundation’s fault . . .

[Camila]: María Luz tells him it’s not his fault, it was País Libre. And Germán clarifies something:

[Germán]: And she’s the one who mostly has been handling this case because . . .

[Camilo]: You can’t handle it?

[Germán]: Well . . . I had a heart attack about fifteen years ago . . .

[María]: Yes, more or less.

[Camila]: Camilo stopped recording at that moment. María Luz asked that he stop talking to Germán about their daughter because of his heart condition. So, we decided not to include his voice in this story anymore.

After drinking something and breathing a little, Camilo turned on his recorder to speak only with María Luz.

[Camilo]: Doña María, please tell me your name and where you come from, where you were born.

[María Luz]: Hmm, my name is María Luz Velásquez. I was born in Guateque, Boyacá. I am 68 years old.

[Camila]: María Luz uses few words. She answers what is necessary and does not elaborate on explanations or descriptions. Some memories make her cry, but as Camilo says . . .

[Camilo]: She has a way of weeping . . . That moved me so much. Her weeping is dry. Not because there are no tears, but it’s like her . . . her . . . her way of gesturing her, her . . . her . . . It’s . . . she’s a person who is tired of crying.

[Camila]: The thing is that María Luz has been weeping for twenty years as she has searched for her daughter, Olga Lucía Ladino Velásquez. She was born in 1976, two years after John Eric, the oldest, and three years after María Luz and Germán married. The first photo in the album is their wedding day.

Back then, María Luz and Germán had a shop where they sold bread, vegetables and grains, as well as two stands in a market place. But their economic situation was not easy. To get a little more money, María Luz worked selecting plastic in a factory.

Seeing the financial situation at home and wanting to help, Olga Lucía began to work in chain stores on weekends. She was still in school. María Luz remembers her this way:

[María Luz]: Friendly. Active. She looked a lot like . . . like her uncles, on her father’s side. Blond hair.

[Camila]: Blonde. She was outgoing, cheerful . . . she laughed a lot and made jokes. She was also very generous and she liked to spend to her very last penny on her family.

[María Luz]: When she worked and got paid, she would call me, “Mom, get ready, we’re going, you know where to, the supermarket.”

[Camila]: She used to take a shopping cart and would always fill it to the top. When it was time to pay . . .

[María Luz]: She did the math and if there wasn’t enough, she turned to look, she smiled and said, “Hold on, mom, I don’t have enough money” (laughs).

[Camila]: She would go to the house, which was not very far from there, and would return with the difference. María Luz and Germán were unable to pay for their children to go to college. When John Eric graduated from college, he served in the military in Bogotá and later met a woman from San José del Guaviare, a town in southern Colombia, in the Amazon rainforest. They had a daughter, and in the mid-nineties he went to live down there, where her family was.

At that time, Olga Lucía had started doing a computer course and was working at a stationery store. There she began to contemplate the idea of going to visit her brother in San José del Guaviare. She wanted to be with her niece, get to know the area, and get a job to pay for her return.

In 1998 she traveled more than twenty hours. First by bus and then by boat. She was 22 years old. At first, she went to live with her brother and his wife. She started working on various things, whatever she could find.

[María Luz]: She worked at an ice cream parlor, a cafeteria, then a convenience store, then in a bookstore.

[Camila]: Living with her brother and wife was not great, so a few months later she went to share a room with a friend she had met there. Her name was Yesenia Sánchez, and according to what she told her mother, Yesenia had helped her a lot while she got used to San José del Guaviare.

A year later, in December 1999, Olga Lucía was able to save enough money to visit her parents in Bogotá. On that trip, she told María Luz that the situation there was difficult.

[María Luz]: Rents are expensive, the food is expensive . . . Jobs last for about two months, and that’s it. They find someone else for another two months and it keeps on going. There’s never any money, I don’t know.

[Camila]: Still, Olga Lucía was determined to go back. She had already lost her job at the convenience store and she couldn’t find anything else to do in Bogotá. But Maria Luz thought it was better for her to stay with them until she found some stability.

[María Luz]: I said to her, “No way, send resumes and . . . and wait, be patient. No, there’s no rush right now, calm down, wait, and when you least expect it, you’ll get a call from somewhere.“

I cried and begged her not to leave, but she ignored me.

[Camila]: Olga Lucía insisted on working to help them out According to her, she had already been offered something down there.

But what she had told her mother about San José del Guaviare, that it was expensive and that there were few jobs available, was only part of the reality. That area of the country was especially violent because of the coca plantations and illegal trafficking, which caused the armed conflict to intensify. There were kidnappings, extortions, murder of civilians . . . the FARC, the paramilitaries, and the Army were fighting all the time. María Luz didn’t get a clear understanding of all that.

[María Luz]: No, I never imagined this was so delicate. Never. They didn’t even tell me, “Look, this and this is happening over there.” No, no, never.

[Camila]: Olga Lucía didn’t have a cell phone at the time, so she would call her parents from a neighbor’s phone.

[María Luz]: When she left for San José she called me every three days. Above all else, she would call me. And then she suddenly didn’t call. She never called me again.

[Camila]: That was between July 12th and 13th. They had spoken a few days earlier, and Olga Lucía had told her that she wanted to learn how to drive a motorcycle. María Luz thought she had gotten into an accident.

[María Luz]: But what happened? Surely, she went somewhere to learn how to ride a motorcycle and she fell on her head and she’s a mess, she’s in a hospital, she’s . . .

[Camila]: The relationship with her son was difficult. They had began to grow apart since he left for San José del Guaviare. But even so, María Luz knew that if something serious happened, he would notify them immediately. That reassured her a bit.

But a week went by and Olga Lucía still didn’t show up. That was very stressful. Maria Luz had asked her some time ago for the number of the neighbor from where she was calling. So she looked it up and dialed.

[María Luz]: I tried to talk to that lady: “Please, look, you’re speaking with her mother. She hasn’t called me and I wonder why.” And she said, “Honestly, I haven’t seen her for about a week. Call me in fifteen minutes and I’ll find out. I know where she lives. I’ll go and ask.”

[Camila]: Fifteen minutes later, María Luz called her again. Olga Lucia lived in a room in a larger house. Her neighbor asked the owner of the house about her, but he said the same thing: they had not seen her for a week.

[María Luz]: So, I said to her, “Could you . . . could you do me a favor and . . . try to get in touch with my son . . . so he can call me to see what . . . to ask him what happened, what happened, where his sister is?”

[Camila]: But he didn’t know anything either. Yesenia, the friend with whom she shared the room, had gone to Bogotá three days before and had stayed with María Luz and Germán one night. María Luz had asked for her phone number to keep in touch, so when she didn’t hear from Olga Lucía she called to see if Yesenia had any information about her. There was nothing. Yesenia had no idea what could have happened to Olga Lucia.

When she realized that her daughter was not showing up, María Luz decided to go to the authorities. First, she went to the Defensoría del Pueblo, an institution that protects human rights.

[María Luz]: And I asked them, “What is your advice?” Is it essential for me to go there directly to see if I can find out something, how it happened? And they told me to go as soon as possible.

[Camila]: A month later, María Luz and Germán managed to collect some money for her to travel to San José del Guaviare. It seemed like a good idea for Yesenia to accompany her because she was closest to Olga Lucia.

[María Luz]: She knew her way around there, she knew where to ask, what to do. She told me, “Well, we distribute cards. We do it there . . . we distribute pictures, we ask.”

[Camila]: Since Yesenia didn’t have much money, they paid for her trip. It was more than twenty hours by bus and boat. But when they arrived at San José del Guaviare, Yesenia went off on her own very quickly and left her alone in her search. The only option Maria Luz had now was to go to her son and ask him for help. Since the town is not that big, she was able to find his address by asking people.

Her son received her but was not very willing to help her resolve the situation. His wife recommended that María Luz go to a radio station and say that Olga Lucía was missing. Nobody wanted to accompany her, but she managed by herself to place an ad.

[María Luz]: Had anyone seen her name, what . . . what she looked like, what she was wearing, that it had been so many days; but no, they repeated that several times, with no results.

[Camila]: Nobody had any information. Later, María Luz went to the headquarters of the Human Rights Office. There they had her look at photos of corpses without acknowledging they had been buried as NN. None was Olga Lucia’s.

The next step was to go to the Prosecutor’s Office to file a complaint. Yesenia’s partner was an government employee there. But according to María Luz, he didn’t want to help her.

[María Luz]: That man told me, “No, I know she disappeared, but I don’t mess with that. You know that I work here and I don’t know what . . . No, no, I can’t help you.”

[Camila]: She didn’t understand what was happening. She had the feeling that they were withholding information from her. She felt there were people who knew more but preferred to remain silent. The lack of help was evident.

Her son and his wife suggested that she shouldn’t try to find out much more because anyone could be involved with some kind of armed group— guerrillas, paramilitaries, or even illegal Army groups. They didn’t like outsiders asking questions about what was going on in San José del Guaviare.

The son had already received threats over this. The only thing he did was go to the place where Olga Lucía lived, get her things, basically clothes and her identity card, and give them to her mother.

He also didn’t know about Yesenia, who after all, never kept her promise to look for Olga Lucia. In the end, after a week, María Luz returned back home alone.

[María Luz]: Because I couldn’t find anything more to do.

I returned the same way, 23 hours, crying all the way. With more doubts, uncertainty. I returned without knowing anything about my daughter. The idea of getting there was, well, I’m going to find her, I’m going to find out about her, but I got there and it all began.

[Camila], “But I got there and it all began,” she says. By “all” she refers, for one thing to the odyssey she had to live through in San José del Guaviare, that in the end proved to be of no help. But also the trauma, the anguish, and the pain that followed.

In Bogotá, she went back to the Human Rights Office—the ones who had recommended that she take that trip.

[María Luz]: And they said, “Go to the Attorney General’s Office.” The Attorney General’s Office: “Go to the Prosecutor’s Office.” Each agency would say, “Well, then go to such-and-such a place.” And that day I would go wherever they told me to go. I would go there: “So now you have to go to such and such another place.”

[Camila]: And so, she went from one place to the next. But it was not easy trying to find solutions in the midst of so much trauma.

[María Luz]: At first it was very hard. I would go out and stop for five minutes: Where am I going, what car do I need to . . . what transportation do I need to take. Then I would see someone with similar hair or a similar age . . . And I would follow the cars until I could get a good look at the person. I was not well. I tried to kill myself. I didn’t want to have anything more to do with myself.

[Camila]: The Prosecutor’s Office opened an investigation and called some people to give a voluntary version. Among them were Yesenia, who didn’t reveal much about her, and Robert García, a military friend of Olga Lucía, who was one of the last people to see her. According to Robert’s version, at dawn between July 12 and 13, 2000, he was with Olga Lucía and a friend of hers, whose name was María Mercedes Rivera, in a bar.

[María Luz]: It’s on a diagonal from the church, and once there, three motorcycles arrived and took them away. My daughter Olga Lucía, and María Mercedes Rivera, who goes by the alias of Angélica.

[Camila]: They were taken by force . . . the alias was because María Mercedes supposedly had ties to the FARC. According to Robert . . .

[María Luz]: At dawn, more or less when they were taken away, gunshots were heard and a girl shouting, “Don’t kill me, do it for my children.”

[Camila]: María Mercedes had four children and also disappeared that night. Although there may have been other witnesses to what happened, no one lodged a complaint and the authorities didn’t investigate. In San José del Guaviare at the time, the State was practically absent. And that hasn’t changed much.

There is no statue of limitations on crimes of forced disappearance because these are crimes against humanity. That means they will never be able to close the case. Although the Prosecutor’s Office has not advanced much further in the investigation, it must continue until it finds the whereabouts of Olga Lucía.

María Luz never stopped looking for her daughter at all. That’s why she came to País Libre. In addition to legal advice, she was offered psychological support and workshops, and she was able to share her experience with other people who had suffered similar cases. She liked that.

In 2008, when she was told about Camilo’s project, she liked the idea. Maybe someone who knew what had happened to her daughter would see her pictures and be encouraged to say something. María Luz looked for the old photo album, with metal rings, hard cover, and a woman on the front with a red scarf on her head. The same one that had gotten wet a while back and had the pages slightly damaged. There were the childhood photos of her daughter.

She gave it to someone at País Libre. But the days passed and they didn’t confirm any activity. María Luz asked the secretary of the Foundation and she replied that they were no longer going to do anything.

[María Luz]: And I said, “And my album? Because I left the album, I’m here to get my album.” They looked for it, “No, it’s not here.” “Please have it for the next meeting.”

[Camila]: But at the next meeting the album didn’t appear either. No one at the Foundation knew where it was.

That album contained the best memories of her daughter, and they were almost the last photos she had of her because she had given the rest to all the agencies she had visited. Someone at País Libre gave her a supposed phone number for Camilo, but María Luz called and no one answered. She then confirmed that the number was not his.

But twelve years later, she received the totally unexpected call from Camilo.

[María Luz]: No, I thought I was dying at that moment, I felt I was about to fall, I forgot . . . I was in shock, I didn’t even know what to answer, whether to scream or what to do.

[Camila]: Because so many years had passed, María Luz couldn’t believe it. She had already made up her mind that her album was not going to appear.

And an idea came into her head . . .

[María Luz]: Is that what’s going to happen with my daughter?

[Camila]: That one day, unexpectedly, Olga Lucía calls again.

When Camilo gave them the album, he felt he had fulfilled the mission that began in November 2019. That’s why he wanted a video record of the moment that moved him so much.

[Camilo]: And I shot, I don’t know . . . three, five photos, crying behind the viewfinder, but at that moment, I knew that . . . that my story had an end.

[Camila]: The story of Camilo did, but not the story of María Luz and Germán, who are still waiting for Olga Lucía in the same house where they have been for more than 35 years. They have refused to move, to go to a more comfortable place without stairs so that Germán can get around more easily. We asked María Luz why, and the reason, for her, was very simple:

[María Luz]: Because it’s the memory of her. Here she left us, let her come and find us here.

[Camila]: Here she left us, let her come and find us here.

[Daniel]: Olga Lucía’s case is already known to the Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas dadas por Desaparecidas, an agency that emerged with the peace accords to try to find people left missing by the armed conflict. They have already begun to collect information, but due to the pandemic, María Luz has not been able to continue the process.

The idea is to start an investigation, rely on what the Prosecutor’s Office has found, and find Olga Lucía’s whereabouts. But this investigation is extrajudicial in nature, that is, it does not have legal implications, nor would it lead to the trial of any potential perpetrators.

There is still no consensus on the number of people who disappeared during the armed conflict in Colombia. One of the reasons is that only since 2000 has enforced disappearance been considered a crime in the country.

There are sources that speak of around 80 thousand, but the Unidad de Búsqueda, which also investigates cases of kidnapping and forced recruitment, raises that figure to more than 120 thousand.

Camila Segura is the editorial director of Radio Ambulante. She co-produced this story with David Trujillo, producer. They both live in Bogotá.

This story was edited by me. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri. Desirée Yépez did the fact-checking.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Nicolás Alonso, Lisette Arévalo, Jorge Caraballo, Aneris Casassus, Victoria Estrada, Xochitl Fabián, Fernanda Guzmán, Remy Lozano, Miranda Mazariegos, Barbara Sawhill and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.