The Giants of the Lake – Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

Children: The hippopotamus… hippopotamus, the hippopotamus.

[Daniel]: This is a video published in May 2019.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

Children: The hippopotamus, the hippopotamus, the hippopotamus . . .

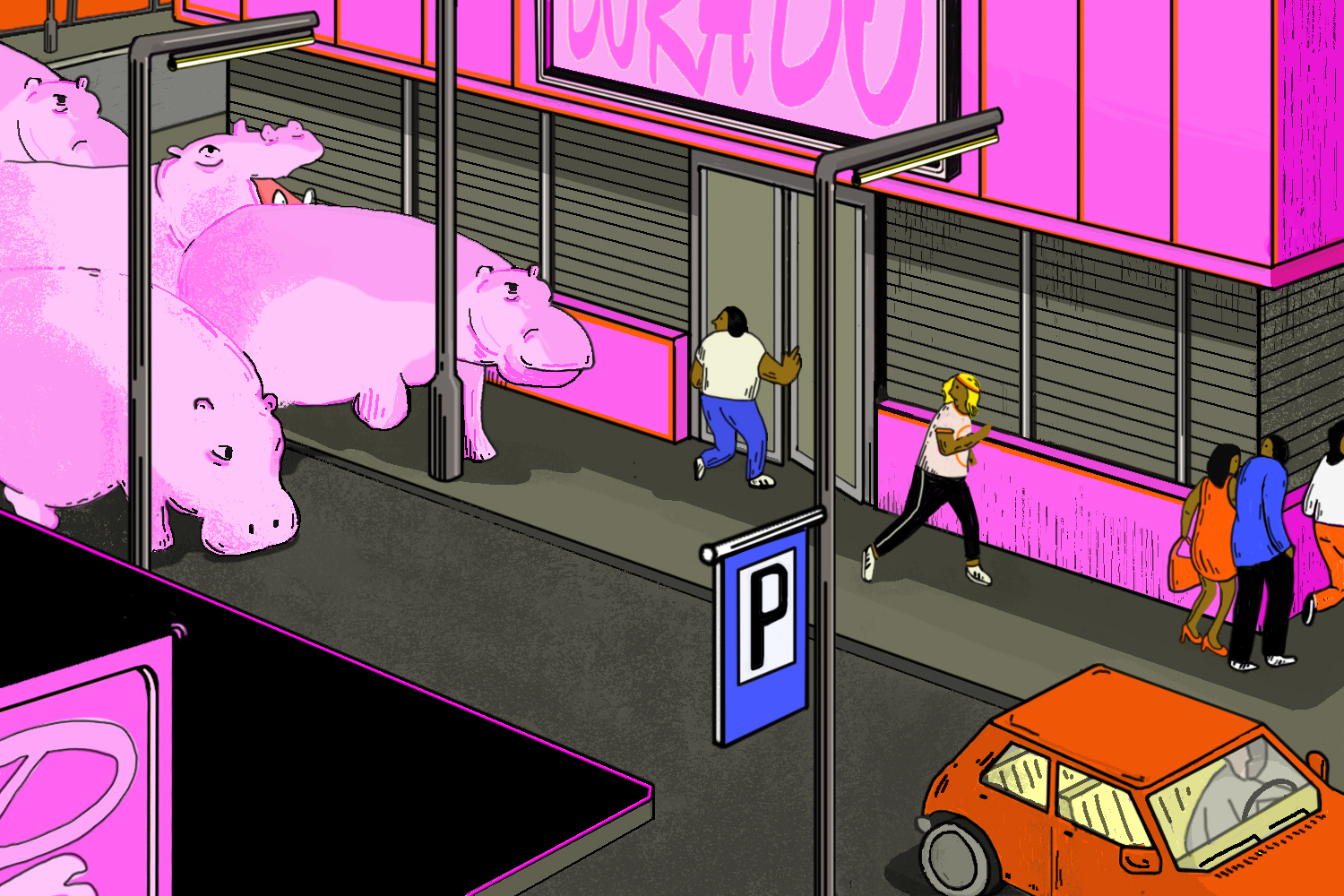

[Daniel]: A hippo. Strolling, calm as you please, down the streets of Doradal, a Colombian town near the Magdalena River. It is night and it walks slowly. You can’t see the screaming children. You see only the animal. It’s huge. Impossible to calculate its exact size, but it looks like a small, heavy car . . . sooo heavy.

OK, I don’t know about you, but for me to see a hippo is amazing in any circumstance. If one were to appear on the street where I live, I would scream like those children, too. And I would probably be even more frightened. But for the people of Doradal, this is not the first time they’ve seen a hippopotamus. In fact, they’ve been watching them walk around the area for more than a decade.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: A group of people just enjoying a sunny afternoon were shocked when they saw a hippopotamus walking along the banks of the Magdalena River. The incident occurred in Puerto Triunfo, Antioquia, where other animals of this species have already been sighted.

[Daniel]: There are reasons, of course, to be scared. Hippos are magnificent animals, without a doubt, but also among the most dangerous on the planet. In Africa, more people die from hippo attacks than from any other animal. And let’s bear in mind there are also lions, crocodiles, rhinos, you know . . .

At first glance, they may not be as intimidating as other species. But they hide secrets. For example, each of their ivory tusks measures between 45 and 50 centimeters. If they feel someone is invading their territory, they usually open their mouth to let them know. And of course, that warning must be taken seriously. A hippopotamus bite is more powerful than a shark bite. Only some crocodiles beat them in strength.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: This is a scene that sends chills down your spine. It happened on the Magdalena River, when some tourists were paddling a canoe and they came across a hippopotamus.

[Daniel]: And although they’re up to five meters long and can weigh as much as five tons, it’s not so easy to see them. Because they spend several hours a day in the water and can submerge for five minutes, they may surprise you if you’re distracted on the river . . .

Evolution led them to adapt to extreme conditions in order to survive, and that’s why they prefer to attack rather than flee. They fight to the death with other animals for water, territory, and food, which is usually grass, flowers, leaves, and fruits. Although they have been known to eat meat when there’s nothing else.

Hippos are African animals and that’s the only continent where they should live in the wild. They should, yes . . . but despite this, Colombia is the only place outside of Africa where you can find a herd of wild hippos.

And although it may sound picturesque, their presence has brought very serious ecological and social repercussions. How did they get there? It’s a story of negligence, mistakes, ignorance . . . but it also has to do with a man who controlled that region near the Magdalena River—well, actually, almost the country. One of the richest and most violent men in Colombia. One who didn’t want pigs, chickens, cows, or any other common animal for his ranch. He wanted a more striking animal, an animal the size of his ego.

That man was Pablo Escobar.

David Trujillo takes up the story.

[David Trujillo]: I’m pretty sure you’ve heard of Pablo Escobar. In case you haven’t, he was the bloodiest, most powerful and most famous drug trafficker in Colombia—one of those guys used to having his every whim come true. In 1978, in a fit of lavish expenditure, he began to build the gigantic Hacienda Nápoles, almost four hours distant from Medellín. He had been buying a lot of land in the Middle Magdalena area for some time, and now he owned a property of almost 2,000 hectares. That’s equivalent to more than 420 times the Zócalo, the largest plaza in Mexico, or almost six times Central Park in New York.

He had everything built on that land—a luxury house with lots of rooms, six swimming pools, dozens of artificial lakes, an airstrip, a heliport, his own gas station, and even a bullring.

This is how they described the ranch, years later, on a television special:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: The small plane that decorates the entrance has the reputation of being the one that brought the first shipment of drugs to the United States. And inside, there’s the most expensive zoo in the country.

[David]: What happened is that since 1981, Escobar became obsessed with getting exotic animals, as if he were a kind of Noah and the Hacienda Nápoles his ark. Little by little, he started bringing all kinds of species—elephants, camels, zebras, giraffes, deer, kangaroos, ostriches, buffalo, flamingos, pink dolphins, and, of course, hippos . . .

Many years later, his son would tell, in a book, that he bought them through animal dealers in the United States. He had enough money to buy several specimens of whatever he wanted. At that time, Forbes Magazine estimated Escobar’s fortune at three billion dollars.

The first animals arrived by boat, but since the process was complex and took a long time, Escobar preferred to start using some of his private planes. He had several that flew unrestricted and he used them to carry tons of cocaine as if that were a normal thing to do. No authority dared regulate the arrival of exotic animals at the ranch, but it’s believed that there were around 1,200.

At that time, Escobar got four hippos—a male and three females. Since they spend most of their time underwater and they live in groups, he tried to replicate those conditions. So he designated one of the lakes for them.

Around 1982, he opened to the public that huge zoo without cages, where the animals roamed free on the almost 2,000 hectares of land.

But Hacienda Nápoles was not just his vacation spot. From there, as we said, tons of cocaine left for the United States.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Police Commander]: But yesterday, at the Nápoles Ranch, a Hughes 500 helicopter, a Twin Otter plane, and five small aircraft for three, four, five passengers were seized . . .

[David]: In the late 1980s, when his drug empire began to crumble and the authorities began looking for him by air and land, Escobar stopped going to Hacienda Nápoles. Ads like this were commonly seen on television:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Announcer]: Pablo Escobar is wanted. Reward: 2.7 billion pesos . . .

[David]: Over 3 million dollars at the time. Finally, in 1993, after months of intense searching . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: Extra! Caracol presents an extraordinary, breaking news report.

[Journalist]: Your attention! We have confirmed information. The team searching for Pablo Escobar has just killed the head of the Medellín Cartel in an operation carried out in the vicinity of Plaza de la América . . .

[David]: He was gunned down on the roof of a house while trying to escape, and the photos went around the world. One of them shows eight armed men. Some in police uniforms, others in civilian clothes. The men surround his body, which lies bleeding on the roof. They’re smiling, as if celebrating that they hit their target, and next to them they have their trophy.

The Hacienda Nápoles, the great symbol of his years of impunity, was already in decline. The authorities raided it several times in the early ‘90s. Many people had gone in and destroyed part of the buildings, looking for millions of dollars supposedly hidden there.

There’s no official record of how many animals there were when Escobar died, nor of the conditions in which they lived. They had been practically on their own for years, although, apparently, with no great food shortage, because that area of the Middle Magdalena is fertile, with vegetation all year round.

It was not until 1998 that the government decided what to do with these lands.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: It’s the first time the presidential helicopter has landed on the grounds of what was once considered a drug-trafficking paradise. There, the president handed over this important property to people who had been displaced by violence.

[David]: About 15 families would start living there. The authorities adapted some cabins that already existed and provided resources so they could devote themselves to agriculture. During the speech to mark this hand-over, President Ernesto Samper entrusted them with the care of the animals.

The following day, Escobar’s family spoke . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: Pablo Escobar’s family will sue the national government for what it described as an abuse by the Executive power in expropriating the Nápoles Ranch.

[David]: And so, a legal fight for the property began. Over time, the families that lived there denounced the State for not fulfilling its promises. The authorities confirmed the state of decay of the hacienda, and it was learned that armed groups moved through those lands as if nothing had happened.

Six years later, in 2004, a judge finally ruled that the property would remain in the hands of the National Narcotics Directorate, an entity that no longer exists, but which at that time was in charge of managing the assets seized from drug traffickers. They decided to build a jail on part of the grounds and get rid of the animals as soon as possible. Many were known to be captured and sent to different zoos inside and outside the country.

The only ones that remained there were the hippos—and it’s not that hard to guess why. We already know they do not like to be disturbed, and you can imagine how difficult it is to try to get them out of a lake where they spend most of their time underwater.

As explained by the National Narcotics Directorate, since 1985 the animals were in the hands of an environmental agency that also ceased to exist. For this reason, they insisted they had no technical or legal responsibility for the hippos, and chose to leave them on the ranch and ignore them.

The State gave the rest of the land to the municipality of Puerto Triunfo, where the ranch is located, to carry out production, environmental, and tourist projects. But for three more years, they remained abandoned. It wasn’t until 2007 that the Mayor’s office in Puerto Triunfo signed a 20-year contract with the Atecsa company to set up and manage a tourism megaproject with a hotel, swimming pools, and other attractions. With that decision, they evicted the displaced families who had lived there for about nine years.

The project would be called the Hacienda Nápoles Theme Park, and the main plan was to recreate a zoo, but with new animals.

[Jorge Caro]: When the Nápoles Park was about to open, they contacted the Medellín Zoo to ask if they could recommend a wildlife veterinarian to help them with a project they had in mind.

[David]: This is Jorge Caro, and he was the vet they recommended.

[Jorge]: Ever since I was in college, I’ve always been interested in . . . wild, exotic, wild animals and . . . yes, I have always worked with them.

[David]: The park people were looking for someone who could take care of the wildlife they planned to obtain, and Jorge was the right person. The idea was to sign agreements with animal protection organizations and zoos to receive animals rescued from circuses or from illegal trafficking of species.

Jorge liked the idea, even though they didn’t have the animals yet.

[Jorge]: At first, the area had nothing of what was meant to become Nápoles Park. The hippos that were loose in the hippo lake were simply roaming around the park.

[David]: He had already heard of the hippos—and he knew they weren’t really confined. They lived in a lake, with no fences enclosing them.

[Jorge]: It’s basically an accident that the park has them in there. The hippos were right there where they are, and they just do whatever they want, whenever they want.

[David]: In other words, although they were in the lake most of the time, they had always been free. Escobar fed them at first, but by 2007, when Jorge arrived, they had already been living on their own for about 20 years, and in unusually optimal conditions. They ate grass, vegetables, and fruits, which can be found throughout the year in that area.

Besides, they had nothing to worry about. What controls their populations in Sub-Saharan African countries are droughts and predators: lions, crocodiles, hyenas. But the largest carnivore to be found in Colombia is the jaguar, and compared to hippos they’re pretty small. The largest are under 100 kilos. And they hunt alone, not like the African predators, which attack hippos in a group.

Jorge’s first task was to tend a calf that the herd had apparently rejected and was dying. They rescued it and cured it, and it’s an emblem of the park to this day.

But beyond that, Jorge and his team wanted to know exactly how many hippos were in the lake. But it was not easy at all. At night, the hippos went out looking for food, and in the morning not all of them came back.

[Jorge]: Some stay in other lakes, nightfall catches them, or they prefer to stay elsewhere. Basically, we saw them, well, I knew—we did a sort of inventory to find out how many were there, more or less. They’re in good shape; we saw young ones. We managed to count at the most 21, 22 animals when the park first opened.

[David]: It had been 26 years since Escobar brought the first four, the three females and the male. And since a hippo pregnancy lasts between seven and eight months, there could easily be a lot more than the 22 that were visible in the lake. Jorge had seen the original hippos as a child, but this was the first time he had seen such a large herd in the wild.

[Jorge]: Yes, it’s shocking. For those of us who love animals and know that our largest local land animals are tapirs and Andean bears that in the best of cases can reach 250, 300 kilos, to suddenly see a beast weighing several tons and roaming free—yes, it’s shocking, it’s emotional, a mix of emotions, you know? Very strange.

[David]: But he knew perfectly well that this was a problem. A serious one. A hippo’s aggressive behavior is by instinct, so those born in captivity, like the ones at Hacienda Nápoles, are also aggressive. Nobody in Colombia was prepared to deal with these huge, heavy animals, which, surprisingly, can run faster than Usain Bolt, the Jamaican athlete considered the fastest human in the world.

And one thing was clear: the park area was so large that they could get out of it and no one would notice. Without fences or anything to contain them, they could enter nearby farms or even reach villages.

[Jorge]: Not even the government had taken up that problem. So we knew there was going to be a problem, but the truth is, well, there was very little we could do, aside from continuing to observe and monitor what was happening.

[David]: According to Jorge, the environmental authorities already knew about the problem but were not very clear on how to act. They were just beginning to discuss who should solve it.

The park managers focused on adapting the place and receiving the rest of the animals that would be part of the new zoo. Those started arriving toward the end of 2007.

Regarding the hippos, which, remember, at that time were estimated at more than 20, the decision was made to continue observing them and collect information on their behavior. They were also fed daily to keep them from straying too far. Since then, Hippo Lake has become one of the most popular attractions in the Nápoles Park.

A few months later, in 2008, the Ministry of the Environment decided to contact an expert on the subject. They called Carlos Valderrama.

[Carlos Valderrama]: I’m a veterinarian, and I work in conservation of ecosystems in Colombia.

[David]: At the time, Carlos ran the Neotropical Wildlife Foundation, which worked with different communities across the country to prevent conflicts between wild animals and people. The Ministry called on him because they were already getting reports from inhabitants of the Middle Magdalena area, who said they had seen a huge, unknown beast walking near the towns or swimming in the rivers . . .

[Carlos]: It appeared only at night—a giant, with large teeth, and people were fearful.

[David]: Very quickly, Carlos and his team understood that it was one of the hippos. At least one of them was outside the park, and authorities were already receiving reports that it was eating crops, attacking livestock, and even hitting fishing boats.

The ministry decided to summon not only Carlos and his foundation, but other institutions and experts to propose solutions. It was already a known fact that one of the lakes in the Nápoles Park was home to a herd, so they went there to try to get an understanding of why they were straying so far away. That´s when they realized a key fact: As is often the case with African herds, the young males were fighting with the dominant male. And that caused them to flee in search of their own territories, even outside the park limits.

[Carlos]: One of these males was the one that came out and was found in the villages near Puerto Olaya, in Santander. That’s very far. We’re talking about almost . . . over 100 kilometers away.

[David]: There were also reports that he had escaped with a female and a calf, so the organizations agreed to go find them in Puerto Olaya and capture them. Of course, it didn’t make much sense to try to return the male to the park, because he was just going to fight the dominant male again and he would end up leaving. So the best option was to find another place that would take them, such as a zoo.

And everything would have been different if the hippo had ended up in a zoo. Maybe tourists would still visit him and take pictures of him.

But none of that happened. After a year of searching, in July 2009, the breaking news was . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: Good afternoon. Noticias Caracol learned today about several photographs that appear to show the killing of at least one of the hippos that escaped from the Hacienda Nápoles, owned by drug trafficker Pablo Escobar.

[David]: One of those photos was the one that impacted people the most. It shows 15 soldiers in the rural area of another town, called Puerto Berrío, very close to where the sightings had been reported. In the background, you can see a river. The soldiers, carrying their weapons and wearing camouflage uniforms, surround the body of a hippopotamus. Some are standing, others crouching. One of them puts his hand on the animal’s head, as if touching a trophy. And, to be honest, it’s difficult not to associate this image with the photo of Escobar’s body taken in 1993.

That’s when the controversy began.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: The animal protection associations and foundations protested to the Ministry of the Environment in Bogotá, demanding that the lives of the remaining hippos be respected.

[Protesters]: “No to the slaughter of the hippos at Hacienda Nápoles!”

[David]: In those days, a magazine called “Don Juan” had published a feature story about the search for the hippopotamus, in which it stated that the people of the area had already given him a name: Pepe. The journalist says she couldn’t find him, because maybe he’d already been hunted down. And, well, she was right. What she does narrate is the sighting of a supposed female, although it must be borne in mind that it’s very difficult to distinguish the sex of a hippopotamus, because males have internal testicles. They can’t be seen with the naked eye like other species.

But that his name was Pepe and that, supposedly, he had left behind a widow and a calf, moved the public, and the media. They even named the other hippos: Matilda and Hipo [Hiccup], and started demanding that they not be killed.

These are radio interviews with some of the protesters:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Protester 1]: They deserve a home to live in and not be murdered.

[Protester 2]: We demand they be given a more stable place. They still have the right to live like all of us.

[David]: The protesters also demanded explanations of how and why Pepe had been killed. At that time, the Minister of the Environment was engineer Carlos Costa, who had just been appointed to that office a few months earlier.

This is Costa:

[Carlos Costa]: When I joined the Ministry, well, I wasn’t aware of the issue. I was, later.

[David]: Costa knew little about these hippos.

[Carlos]: In my opinion, this is a relatively minor issue compared to the complexities and responsibilities of environmental policy.

[David]: And according to him, the issue belonged directly to the regional environmental authorities, which also have autonomy to make decisions. Even so, the ministry supported the process of Pepe’s capture as regards the decision-making and logistics.

But, as we already said, hippos are huge animals and can be very aggressive. Capturing them in the wild is very difficult. Those seen in zoos are usually rescued from animal trafficking when they’re young, or are descended from others that were already in captivity.

Costa states that they proposed the option of trying to capture it like any other smaller animal. But, he says, they had no references to know how to proceed.

[Carlos]: There are no previous experiences in the world of how to make a cage and a trap to capture a hippopotamus. Here we spent a year trying, but it was not possible.

[David]: And they couldn’t find a national or international zoo that would take it. To begin with, this was a wild animal that could carry disease and spread it to other species. But also, hippos need special conditions that include a large aquatic area, living in a herd, and lots and lots of food.

This is the administrator of the Nápoles Park in those days, speaking on a radio station about hippo maintenance:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Óscar Orozco]: One of these animals consumes 10% of its weight in grass as daily food, and the average is one and a half tons. In other words, it’s 150 kilos, and there are 27 animals, so that comes up to 6.7 tons of foliage per day. Or the equivalent of roughly a ton of concentrate per day.

[David]: Former Minister Costa says that they began to review similar experiences in other parts of the world, including populations of wild hippos in African countries.

And so they came to the solution that would later be seen in the photos.

[Carlos Costa]: That’s why the decision was made . . . to adopt culling as a way to handle this situation.

[David]: Carlos speaks of culling because, in reality, there are different types of hunting, each with different objectives. We’re talking from hunting for sport to scientific hunting for the purpose of researching live animals. And, of course, there’s illegal hunting, which traffics in exotic species or parts of them, doing enormous damage to the environment and even leading to the extinction of several species.

Culling, on the other hand, is legal in Colombia and other countries, and seeks to reduce the number of animals of a species in a habitat so that its growth doesn’t affect the rest of the wildlife, or so that it doesn’t become a danger to humans. For this reason, it often has the support of scientists and even environmentalists. Although it’s still controversial.

Although the Ministry explained that it was a procedure with scientific and technical backing, the outrage of the protesters did not stop. They didn’t accept the idea of the army killing animals.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Protesters]: No more killings! No more killings! No more killings! No more killings!

[David]: The issue, additionally, is that, because of factors such as illegal hunting or climate change, hippos are a species in a vulnerable state in countries of Sub-Saharan Africa such as Angola, Kenya, and Equatorial Guinea—one step away from being in danger of extinction. That’s why constant efforts are made to protect them. The protesters considered that the decision to kill Pepe was contrary to those efforts, making it irresponsible and even illegal. They demanded the immediate resignation of Costa, the Minister of the Environment.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Protesters]: Resign! Resign! Resign! . . .

[David]: As the days passed, the news of Pepe’s death began to appear in the international media, and the controversy grew more and more. Bavaria, the leading beer company in Colombia, offered to pay the salaries of other experts, who would find a different solution, other than hunting. And a zoo offered to take Hipo and Matilda if they were guaranteed the resources to accommodate them. One magazine even called for a demonstration in a park in Bogotá, with people dressed in gray and wearing tutus. The idea was to replicate a scene from Fantasia, the 1940 Disney film that features dancing hippos.

With all this pressure on, an investigation was launched . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: The objective of Inspector General Alejandro Ordóñez is to determine whether those who ordered the hunt had committed a disciplinary offense, and at the same time stop the order of execution against the animals.

[David]: On July 22 of that year, 2009, the news came that a regional authority involved in the procedure had published a report on how the hunt went. In reality, it was not the military who killed Pepe. They had been in charge of protecting the area so as not to put people at risk. Those who had shot, the report said, were two hunters hired for that purpose.

This is a radio program where they talk about that report:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist 1]: The report delivered by CorAntioquia reveals the presence of Federico and Cristian Pfeilschneider, two foreigners who appear as the representatives of the Porsche automobile company in Colombia and who were in charge of the hunt for Pepe. However, the report doesn’t mention how they were selected or called in.

[Journalist 2]: Sure enough, as if they were on a safari. On a safari hunting for the hippo in Colombia.

[David]: The report also said what they were going to do with the body of the animal:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist 1]: The report says textually, the following, Yolanda: “The resolution mentions the disposal of the corpse or corpses—remember that they were going after Pepe and Matilda, who is the female hippopotamus— where the viscera should be buried, and the carcass—this refers to the body of the animal—to be transported to the private collection of Mr. Federico Pfeilschneider in Bogotá”.

[David]: Federico Pfeilschneider, one of the two hunters mentioned.

In the program, the journalists also talk about other photos of Pepe’s hunt, which were not published but were included in the report:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist 1]: They’re terrible, Yolanda. One of the creepiest parts of the report is a photograph showing how the men who participated in the mission are making incisions in the hippo’s legs. In addition, another of the photographs shows how the animal—they had a taxidermist on board with them on this mission, and the back of the head was skinned so that, well, so it was already detailed for the collection . . .

[Journalist 2]: So they can hang it on the wall.

[Journalist 1]: So they can hang it on the wall.

[Journalist 2]: That’s the objective. And they had a permit for that.

[David]: The controversy over the hunt for Pepe was far from over. Although the ministry, under pressure from the media, stated that they were not going to hunt Matilda and her supposed calf, Hipo, there were still many doubts up in the air. Even a major newspaper journalist began to speculate what the real interest had been behind the decision to hunt him down. Ivory moves millions of dollars on the black market, and it’s still a very difficult, dark business to fight. Hence the journalist’s question: Where was Pepe’s head, and his ivory tusks?

On July 23, the whereabouts of Pepe’s head became known. Two days later, this report was broadcast on television:.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[María Cristina Uribe]: Neighbors of a farm in Guasca, Cundinamarca, began to notice a strong odor. Only the most imaginative figured out the origin: the head of the hippopotamus. Yesid Baquero . . .

[Yesid Baquero]: Well, María Cristina, we went to Guasca to see the grave where Pepe’s head is.

[David]: Guasca, more than seven hours from the place where he had been hunted. The journalist had learned of complaints by townspeople to the police, where they claimed that Pepe’s head was on a piece of land in the area. The smell indicated that there was something large buried there . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: Noticias Uno came to the place where there was nothing but a horse, an empty house, and this hole covered with branches where the skull of the mammal weighing over 2 tons allegedly was. Apparently, the residents of the area knew nothing about Pepe, but they did know about the owner of the land.

[Neighbor]: I understand that it belongs to Carlos Valderrama . . .

[David]: Carlos Valderrama, the Neotropical Wildlife Foundation vet we heard earlier. The same one that the ministry contacted as an expert in preventing conflicts between communities and wild animals. Carlos was interviewed on that same television newscast, and he confirmed that this was his property and that the hippo’s head was indeed buried there.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Carlos Valderrama]: The head is complete. It has all its . . . its accessories. The head was simply removed and buried just as it was when it was taken.

[David]: He also said that it was not a hunting trophy, as had been speculated, but that it would be donated to a museum park on the outskirts of Bogotá, the Jaime Duque Park. Although he did not clarify the reason for the decision to display it, he did explain why it had to be buried:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Carlos Valderrama]: So that the decomposition process continues without producing bad smells.

[David]: But they must have been doing something wrong, because it was precisely the bad smell that attracted the neighbors and then the journalists. In any case, the idea behind burying it is that the soft tissues decompose and only the skull remains. After that, it undergoes a taxidermy process so it can be exhibited.

Those explanations were given by Carlos, but the story of the head persisted in the media. On July 27, one of the hunters was interviewed for the first time on a radio show. The same one who, according to the report, was to receive the head for his private collection.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Julio Sánchez Cristo]: He is Mr. Frederick Pfeilschneider. He’s the man who killed Pepe.

[David]: Although he has a German name and was living in Germany at the time, he is Colombian. He is also a professional hunter for the Colombian Shooting and Sports Hunting Federation.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Julio]: Mr. Schneider, who asked you to carry out this job?

[Frederick]: I was contacted by Dr. Carlos Andrés Valderrama of the Neotropical Wildlife Foundation.

[David]: About the hippopotamus, he said, he knew little, only what had appeared in the news: that it was male and had left the Nápoles Park, perhaps with a female and her calf. In the interview, the journalist says that to hunt a hippo with the least suffering, you need experience, very good aim, and a specific weapon with deadly ammunition. Pfeilschneider had all of those.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Julio]: Mr. Schneider, what kind of weapon did you use to kill Pepe?

[Frederick]: A .375 rifle.

[Julio]: How far were you from Pepe?

[Frederick]: About 80 meters.

[David]: They asked him if what motivated him to accept the task of killing him was to keep the head, and although he clarified that they did offer it to him at first, he stated that he himself rejected it . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: So, if you decided to decline that proposal, did you charge any kind of money to kill the animal?

[Frederick]: Oh, God, no. I did this as a favor they requested because I know the danger of that procedure, and because I have the experience and the appropriate weapon and the necessary aim to do it.

[David]: The idea of keeping the head, Carlos Valderrama explained to me, was to arrange an educational exhibit against illegal wildlife trafficking, the very reason that had brought the hippos, years ago, into the hands of Pablo Escobar.

All of this was specified in a legal permit issued in June of 2009 by the Central Antioquia Regional Corporation. The entire procedure and the environmental reasons for it are detailed there. And it makes something clear: if the calf is found, they must consider the possibility of capturing it alive and taking it to the Jaime Duque Park.

[Carlos]: Everything was done following the protocols that must be followed. “He stole the head.” What do they mean, I stole it, when the document says that I took it with me? There’s a transport permit for the head where I say that I’m going to take it in order to do the procedure.

[David]: Once the taxidermy process was ready, Carlos stated, Pepe’s head would arrive intact at Jaime Duque Park. And that had not been his decision. The hippos are part of the property seized by the authorities at the Hacienda Nápoles.

[Carlos]: These hippos are the property of the State. So the fate of the hippos and the fate, whether alive or their parts, if an animal is killed, it’s a decision by the government or by the competent environmental authorities.

[David]: In August 2009, after a few weeks of controversy over Pepe’s death, the Inspector General’s Office reaffirmed that everything had been legal, but recommended that the National Narcotics Directorate adopt a wildlife management policy. Although that’s as far as it would get, a recommendation.

One thing was very clear: killing another of the hippos from Hacienda Nápoles would be extremely sensitive. Pepe’s sacrifice had seriously affected the image of the Ministry of the Environment and cast doubt on any future decision made on the subject.

Carlos Costa, the Minister of the Environment at the time, acknowledges that they never thought people would care so much about a hippopotamus:

[Carlos]: We did not anticipate that this could be something so . . . with such an appetite for it in the media, let’s say, or that it would generate so many emotions in general.

[David]: That first photo, for example. They never anticipated the impact that such an image could have, with the military celebrating over a corpse, in a country with so many years of war. He also acknowledges another mistake: —not educating the public about how delicate this whole environmental situation was, before pulling the trigger.

And the most serious consequence of this was that the authorities who continued in the Ministry preferred not to face the issue of the hippos . . .

[Carlos]: There was a lot of fear of dealing with that situation after all the visibility that . . . that managing the animals’ control had generated. And later, the subject was hidden, it was . . . it was ignored.

[Daniel Alarcón]: But sooner or later, a herd of two-ton animals was going to become a problem. The hippos were still there, submerged in the water by day, foraging for food at night. And attacking if they felt threatened.

And, of course, at some point, another one would want to go for a walk outside the park . . .

We’ll be back after a pause.

[Daniel Alarcón]: We’re back at Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, we heard how the hunt for the hippopotamus Pepe, who escaped from a ranch belonging to Pablo Escobar, caused enormous outrage in Colombia. Resolving the situation became a very sensitive issue, so the government opted to go no further with the discussion. Maybe later they could find a way to solve it.

But hippos were not a problem of the future. There were about 30 of them already, and they would start to show up more often and in different towns.

David Trujillo continues the story.

[David Trujillo]: In 2010, just a year after Pepe’s death, reports reached the authorities saying there was another hippo outside the park, but this time in a nearby area. There was talk of another young male driven out of the herd. And that put hippos closer to being considered an invasive exotic species.

What does that mean? Well, human migrations have, for millions of years, transported animal and plant species. The danger occurs when these species begin to live and reproduce in the wild, altering the delicate, balanced networks in a habitat very different from their own, and putting native species at risk. It’s not a minor thing—invasive species today are the second cause of extinction of other species worldwide.

For this reason, since 1994, Colombia has signed international treaties and enacted local laws to regulate the matter. In them, it agrees to prevent the entry of these species into the country and, if they’ve already entered, it will control their reproduction or eradicate them. In 2008, an official list of invaders was drawn up: lionfish, bullfrogs, crazy ants, giant African snails . . . but there was no trace of hippos on the list, despite being a territorial species that attacks any individual competing for food or space.

What the Colombian regulations do make clear is that the authorities are obliged to do something, based on what the international agreements say. In short, faced with an invasion of dangerous vertebrates, attempts must be made to contain them—that is, to enclose them. This is so that they won’t affect the new habitat. And if it is not possible to contain them, then they are to be culled.

It all depends on the species, the studies that are done on the speed of their reproduction, and their impact on the ecosystem.

But let’s go back to the hippopotamus that left the park in 2010. When the case was reported, a meeting was held by authorities, the park’s team of veterinarians and, again, Carlos Valderrama, the vet we already heard from.

They had to think of solutions, but since Pepe’s death had been so controversial, they decided that it was best to take a different approach.

This is Carlos again:

[Carlos]: We decided to capture it, neuter it, and return it to Hacienda Nápoles. We hoped that after being castrated, he would not have a conflict with the dominant male and he would not be relegated or displaced again.

[David]: Capture and castrate a wild hippo. You heard Carlos: that was the bet and, well, let’s say there are easier tasks to fulfill. In fact, although castrating males is included in the recommendations of international organizations, there was very little precedent in the world. Among those was one in Israel, which, by the way, had ended in the animal’s death.

And the risk was not only for those who would dare put a scalpel into those two tons of sleeping force. It was also for the hippopotamus itself. With the amount of anesthesia they had to give it, they could easily kill it.

[Carlos]: Hippos have a high fat content in their body, and fat accumulates anesthetics.

[David]: And that can be very tricky because, since the animal doesn’t react immediately to the anesthetic, you may think it needs more.

[Carlos]: You administer it and it accumulates. All that medication is released from one moment to the next, and all of a sudden you have an excess of anesthesia or sedation that can, let’s say, bring the central nervous system down too much.

[David]: In other words, kill it.

But also, in that period until the anesthetic takes effect or doesn’t, there is the possibility that the hippo will get scared, run towards the water to hide, and if it submerges before the dose takes effect, it can drown.

[Carlos]: Everything with them gets complicated. Apart from that, if you can anesthetize it properly, if left in the wrong position it can suffocate because it cannot ventilate due to its own weight.

[David]: But the issue of anesthesia was not the only thing. They also had to think about surgery. Where should they do it? Was it better to take the animal to the park and operate it there, or in the area where it was? And how could they transport an animal of such a size?

Complex logistics were needed, and also money—a lot of money. So Carlos decided to go looking for sponsors for the operation.

[Carlos]: We found someone to support us with the procedure. The Discovery Channel supported the procedure of castration and capture of the animal. It cost us $50,000 dollars. I mean, it’s quite expensive.

[David]: That, Carlos told me, would cover the expenses of tracking the hippo for a few months, cameras with daytime and nighttime motion sensors, and a cage specially designed to capture and transport it. There was also the anesthetic, which was a lot, the darts to apply it, the medications, a backhoe to lift the animal and put it in the cage, and a crane to move it. The whole process would be carried out by a team of ten people, who would work side by side on the castration.

Some veterinarians from the park would participate, together with Carlos Valderrama and his foundation, two universities, the Ministry of the Environment, the regional environmental authority, and even the military, that would provide logistic support. The Discovery Channel, meanwhile, would record a documentary.

The first mission was to find the hippopotamus. Although there were reports of sightings, the area to be tracked was more than 20 thousand square kilometers. That’s about the size of a country like El Salvador.

[Carlos]: We searched, interviewed different owners and people who lived in the area to find out where they had seen it.

[David]: As if they were detectives, the team began to follow the tracks the animal was leaving, trying to trace its movements.

This is part of the Discovery Channel documentary:

(SOUND BITE FROM DOCUMENTARY)

[Carlos]: All these are clearly hippo footprints; they’re too big for a Colombian animal. They’re deep, made by a heavy animal. Here we can even see the four toes of the . . . of the footprint. Pretty exciting. We seem to be on the right track.

[David]: Since hippos usually come out of the water at night to look for food, they decided to put food in various places in order to attract it.

[Carlos]: We put out everything. Carrots, lettuce, anything. We went to the marketplace and whatever we found in bulk, that’s what we got. They eat everything. After all, they’re herbivores, right?

[David]: And in those spots, next to the food, they installed cameras with motion sensors. They reviewed them for several days without success.

Until finally . . .

(SOUND BITE FROM DOCUMENTARY)

[Carlos]: We’re checking the photos the cameras took and, well, we can finally confirm that the hippopotamus is coming to feed at the bait site.

[David]: The camera shoots at each movement, so in the documentary you can see how they review a series of photos. They’re in color, but they’re not very sharp, because it’s night and the lighting is minimal. In the first one, you can see the grass in the area and a mound in the lower left corner. That’s the food. Then, in the other photos, the hippo appears from the right. First a part of the head and its eyes shine from the camera flash. Then come the ears, the neck, the front legs . . . Little by little, his body occupies almost the entire image, until he stops in front of the food. It’s a very large animal. In low light you can see his skin almost hairless, of a color that appears gray and brown, and also reddish.

(SOUND BITE FROM DOCUMENTARY)

[Carlos]: It’s a much larger animal than we expected. I think it’s around 1,500 to 2,000 kilos.

[David]: The photos show the hippopotamus starting to eat. He moves his head in various directions, but you can’t see the tusks in all their splendor. He keeps eating, eating and eating, and the mound shrinks until it’s flat. Then he disappears to the left side of the frame.

Well, now at least they knew where he was, but catching him was something else. Carlos and his team had designed a special cage, and the plan was to leave it at the point where the photos were taken, but this time with the food inside.

[Carlos]: And we had designed a trap for the door so that when he went in, the door would fall and he would be trapped inside the cage. A huge cage, a huge cage and specially designed for them, with skis and everything so that it could be pulled.

[David]: They tried for several days, but each time they reviewed the photos on the camera, they became more certain that the plan was not going to work.

[Carlos]: Unfortunately, we couldn’t get him inside. He never, ever had enough confidence to enter.

[David]: There was not a chance. They had to change their strategy.

[Carlos]: We already knew where he was, so we said, well, we can risk capturing him without the cage, with anesthesia, in order to castrate him and, and once anesthetized, we can place him inside the cage for transport.

[David]: Jorge Caro, the park’s chief veterinarian who was accompanying this process, would be in charge of the delicate issue of anesthesia. This is Jorge:

[Jorge Caro]: We started looking for a spot that offered us the best guarantee for shooting the darts.

[David]: A wide space, away from any populated area. Although that depended less on them than on where the hippo was.

The plan also had other problems . . .

[Jorge]: Medications used to anesthetize mega-vertebrates such as elephants and rhinos are not allowed in the country. They aren’t sold.

[David]: Because, for one thing, there isn’t a considerable demand that would justify the imports. And for another, since these are heavy narcotics, they can be very addictive and extremely dangerous to humans—well, also to hippos.

[Jorge]: They’re not recommended for the species because they generate a lot of mortality specifically in hippos.

[David]: We already mentioned the subject of the animal’s body fat. Jorge had been reviewing studies done in other zoos around the world. Based on that, and on the recommendations of African hippo experts, they chose a cocktail of products that were found on the national market to sedate the animal.

It was still risky, but it was the only option they had left.

By that time, they had been monitoring the animal for three to four months. And, like Pepe, Matilda and Hipo, the team had already named the runaway hippo. They called him Napolitano, in honor of the ranch.

When they finally found him, several days had gone by since the camera took the photos. He was in a small nearby lake. But when they tried to get closer, Napolitano got upset. He started wagging his tail as a warning, dropping excrement. And he made threatening movements, as if to chase them if they didn’t leave immediately.

They decided to postpone the procedure for the next day, but when they were ready to start, the hippopotamus didn’t show up until late afternoon, when it was already getting dark. They had to postpone it for one more day. So the animal wouldn’t get lost again, the army set up a security zone and kept watch all night. They had to proceed as soon as possible or he would continue to escape. And since it was the start of the rainy season, the land was flooding more and more.

And so, they started at 5 o’clock the next morning. Napolitano was still very nervous. A man on horseback, who was helping with the procedure, began to shake a cloth to make him come out of the water, and Napolitano lunged at him. Fortunately, he didn’t reach him, and the cowboy lured him over to a drier spot.

Jorge, the park vet, already had him in the sights of his rifle, armed with darts of anesthetic. But the first dart bounced off Napolitano’s thick skin.

Jorge tried several times. He approached slowly, ducked behind a bush, and took aim with his rifle. He shot. His dart hit the hippo right in the neck. A perfect shot. Then Napolitano, a little confused, started running.

Just what everyone feared . . .

[Jorge]: The animal got into the water and it was a terrible problem to keep shooting darts at it there because it kept needing more doses of anesthetic. The buttock of the animal started to float a bit, so I—I got on the arm of the backhoe, it lifted me about two or three meters in the air. There, I was at a better angle and I could shoot a good dart.

[David]: Carlos Valderrama, from the Neotropical Wildlife Foundation, was there coordinating the entire process. And he was starting to worry . . .

[Carlos]: If we continue to anesthetize him there in the lake, then he’s going to die. It had been an hour already, and he wouldn’t leave the lake.

[David]: Luckily, the team had little piles of gunpowder wrapped in paper, which they had bought to make noise in case the animal ever attacked someone. They could use them to scare it away.

[Carlos]: We put the wrapped gunpowder on the edge, he got scared and left the lake, and there the vet managed to give him another dose of anesthetic, and there he succumbed to the anesthetic and was still. Very close to the lake, but on dry land.

[David]: Napolitano tried to escape, but he already had two darts in him, and he collapsed with his head held high. He was still struggling to blink when Jorge gave him one last shot of anesthetic. The hippo tried to stand up, but he couldn´t manage. A few minutes later, he fell completely asleep.

Immediately, the vets went to work, jumping on the animal to tie its legs and muzzle. Meanwhile, tubes were inserted into his veins in order to inject him with painkillers, antibiotics, and more anesthetic. They then lifted him up with the backhoe and put him inside the cage. Once he was there, the surgical procedure finally began.

The vets, let’s remember, had to open Napolitano’s body, because hippos’ testicles are internal.

[Carlos]: Going in to look for those testicles in the groin area was another tough job. So, let’s say it was uncomfortable and especially because the structures are very strong, very large. Normally a castration lasts 15 minutes, half an hour, no matter how large the animal is. This one took an hour and a half.

[David]: They removed the testicles, which are as large as mangoes, and stitched him up. He seemed to be responding well to the anesthesia, his vital signs seemed stable—that is, everything was going as hoped. What remained was to move him to the Nápoles Park. An Air Force helicopter would lift the cage with a harness. The flight would take three to five minutes, more or less, but it was the first time they ever did something like that.

[Carlos]: The way they explained it was, “We have transported loads of the same weight, but never a live animal.” When you’re carrying a load in a helicopter and the load moves, the same movement of the load is doubled inside the helicopter. I mean, every step seemed more difficult than the one before.

[David]: The helicopter pilot was not too sure the feat would be successful, and demanded a guarantee that the animal would not wake up mid-flight. But there was only one way to be sure: more anesthetic. It was a difficult decision, but they couldn’t leave him there, outside the park.

In the documentary, you can see Jorge Caro’s concern.

(SOUND BITE FROM DOCUMENTARY)

[Jorge]: We are already past the time that we would like to have the animal under anesthesia. Now it’s all about the safety of the flight.

[David]: At some point, he asked the military to hurry as fast as they could.

(SOUND BITE FROM DOCUMENTARY)

[Jorge]: Gentlemen, following all the security protocols, I will ask you to hurry up a little because we have—the animal is getting past its anesthesia time.

[David]: “The animal is getting past its anesthesia time,” he says. It could die . . . so they hooked the cage very quickly and authorized takeoff.

(SOUND BITE FROM DOCUMENTARY)

[Soldier]: Load hook exercise, transport of hippopotamus to Hacienda Nápoles. PAX 07. Kilograms: 300. External load: 2,950 . . .

[David]: It was a critical moment. Any miscalculation, even if it were minimal, could send the helicopter who knew where and result in a fatal accident.

The helicopter lifted, and little by little, the harness attached to the cage tightened. They all looked nervously at the sleeping animal.

Eventually, the cage was lifted off the ground and the helicopter began to move forward. It was a first step, but they still had more than three minutes to go . . .

[Jorge]: It was very hot; the animal was very heavy, and the helicopter started overheating after takeoff.

[David]: Overheating in full flight. In desperation, the helicopter pilot threatened to drop the cage. Imagine a hippopotamus of that size . . . in free fall . . . from hundreds of meters up . . . in a cage . . . CRASH! It would all end there. It was crazy, but for the pilot it was either that or include the helicopter and the passengers in that fall . . .

Carlos Valderrama, the Foundation vet, was very nervous. While talking to the pilot, he would lean out one of the windows to see how Napolitano was doing. Jorge Caro, the anesthesia manager, stared straight at the cage through an opening in the floor. He did nothing else. He didn’t even speak or move. In mid-flight, he had just one thing going through his head . . .

[Jorge]: I think I’d rather we all get killed with the hippo, but I don’t want to see that hippo fall from up here. Can you imagine that?

[David]: They were almost there. The pilot accelerated.

[Jorge]: Finally, we could more or less see the ranch, so he went as fast as possible. We could see the runway on the ranch, and we managed to land, well, without any mishaps.

[David]: Very quickly, they checked that Napolitano was still alive. He was only asleep, but now they had to wake him up. So Jorge ran up to the cage to give him a shot of yohimbine to revive him. Immediately, the animal sat up, after having been sedated for more than three hours. He looked very good. They covered the cage with black cloth to avoid any additional stress.

When they put it on the crane, the front tires lifted because of the weight. But hey, at least they weren’t in the air any longer. Once they stabilized it, they were able to drive to the site where he would be released, very close to the lake where the herd was. Napolitano was calm.

It was already dark.

[Carlos]: It was quite a long procedure. We started at five in the morning and released him at seven that night. We had to wait, he was up, he was standing up, and we released him. And he walked out, went into the lake and stayed about two days in that lake. That’s what they told us.

[David]: After that, Napolitano joined the herd without a hitch. One of the few recorded castrations of a wild hippopotamus, against all odds, had been a success.

Eventually, the park vets lost track of him. He had no obvious markings and it’s difficult to tell one hippo from another. But, in general, they’re very resistant to wounds and have a strong immune system. Most likely he has continued to be well.

However, although Napolitano’s story had a happy ending, the method had been too difficult for it to become the solution to the problem.

[Jorge]: We learned a lot from the experience. So we realized that, although it could be done, it was tremendously complicated, expensive, risky, unpredictable. A number of situations, of variables that . . . that could drastically affect the result, and in many situations it was simply not feasible.

[David]: One year after Napolitano’s castration, in 2011, the Ministry of the Environment published a new plan to manage invasive exotic species. And this time they included hippos on the list.

The plan had several options, including eradication, but the issue remained highly sensitive. In 2012, three years after Pepe’s death and the scandal over his head, a court ruling prohibited the killing of the female and the calf which had supposedly left the park with him. No permits or recommendations for culling. The authorities had to guarantee their capture and relocation.

The ruling spoke about those two animals specifically, although no one knew what they were like or if they really existed. So in practice, it meant the prohibition of any type of hippo hunting in Colombia. And that tied the hands of the environmental authorities, who were limited to creating community education plans to warn of the danger of approaching the animals.

They tried to contain the main herd within the park as much as possible. They tried to limit the lake and the areas where they move within the park with marble, bushes, barbed wire, and electric fences. They also continued to feed them. But it’s not enough, of course. Enclosing hippos is not the same as enclosing cows or pigs and, besides, you have to trust that they won’t knock down the enclosure.

Ten young males have been castrated inside the Nápoles Park, and they are less aggressive and easier to control. In 2018, one of those animals was taken to another zoo, an operation that ended up costing around $5,000 dollars. In addition to that, assurance has been given that four more were relocated.

Environmental authorities know they should sterilize many more to stop their reproduction, but they say the situation is so complex that they’ve been unable to control population growth. And that’s only the ones inside the park, not counting those that live outside.

But one thing is sure beyond a doubt: it’s that the population continues and will continue to grow. Carlos Valderrama compares it to a very famous movie:

[Carlos]: It has the potential to become a Jurassic Park. Of course it does. In other words, it’s like those films that we see, where a population grows out of control, with all the implications this has for the environment and, well, for a population of this type, in a country like ours.

[David]: The difference with Jurassic Park is that there, at least the dinosaurs were on an island; there was an ocean that prevented them from reaching the continent. In the case of the hippos, no matter how large the area of the Nápoles Park is, there’s nothing to keep them from reaching increasingly remote areas.

Jorge Caro, the head of the park’s veterinary team, says it’s a situation that has no comparison.

[Jorge]: I think that Colombia is so exceptional in everything that even in this particular case it’s a . . . —it’s absolutely a Macondo circumstance. Colombia is the only country in the world that has a multi-ton mega-vertebrate as an invasive species.

[David]: Since Napolitano’s castration in 2010, several more reports of sightings have sprung up. And news like this one from July, 2018:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: Inhabitants of two border villages between Puerto Triunfo and Puerto Nare in Antioquia are concerned about the ferocity displayed by two hippos whenever they pass near them in their canoes.

[David]: News like that, in general, remained the same as always—the curious story of the Colombian hippos. But on May 11, 2020 . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Journalist]: Luis Enrique Díaz Flores, a 43-year-old peasant, may be the first person ever attacked in Colombia by a hippopotamus. The events occurred in the rural area of Puerto Triunfo, Antioquia.

[David]: In that newscast, they interviewed a witness to what happened.

[Sader Echeverri]: We were fumigating the pasture and the boy went to collect the water from the spout. He came back with the container flying everywhere and yelling, “The hippopotamus!” So I threw down the motor and we ran away together. Unfortunately, the hippo reached him and grabbed him in his mouth, shaking him from side to side.

[David]: The guy was in shock for 15 days, but he survived. The next day the news came that another person had been attacked in the area, only this time with no injuries.

Fueled by this news, a multidisciplinary group of Colombian scientists wondered how many hippos there were, and how much that population could grow if it continued to reproduce unchecked. In January 2021 they published an article in the scientific journal Biological Conservation. There they demonstrated, using mathematical models, that there are abound 100 hippos in Colombia today. There may be a few more, maybe a few less. But the most surprising thing is the projection. Taking into account the optimal conditions in which they live, by the 2030s there could be—and listen well to this figure—over 1,400 hippos moving through the country! They could even reach the coast of the Caribbean Sea.

And that, the publication warns, could unleash enormous environmental damage. Their large size has an impact on ecosystems. Over the years, their footsteps can change the shape of rivers and lakes, and damage the bottom of the rivers. In addition to the fact that their excrement alters the composition of the waters, they compete very aggressively with other species in the habitats they occupy. Some, like the West Indian manatee, which inhabits the Magdalena River, will surely not survive.

One of the authors of the study is Nataly Castelblanco, doctor in Ecology and sustainable development at ECOSUR.

[Nataly Castelblanco]: It is not a simple problem. It’s a problem that has many facets, and it’s a headache for government agencies, for scientists, for everyone. It is really becoming a very big challenge in conservation.

[David]: The only option, according to the study, is to remove the escaping hippos from the ecosystem. Something the researchers call extraction. This could be done via culling, trying to avoid unnecessary suffering of the animals, and following the ethical guidelines proposed by international organizations.

The other way would be to capture them, but if so, you still have to sterilize them and put them in a type of captivity that works, which doesn’t mean only that they are prevented from escaping.

[Nataly]: A captivity site can be small or it can be huge, but it’s still captivity. Removing an animal that is strictly social, separating it from its herd, taking it alone into captivity so that it lives out the rest of its life—which is not two years, but 10, 20, 30 years—locked up, that’s also an animal that is suffering.

[David]: Because a hippopotamus can live up to 50 years. And for their captivity to be as similar as possible to their habitat, you would have to guarantee them proper land and water areas, a herd, and a lot of food.

[Nataly]: Who is going to be responsible for the maintenance of all these animals during the next decades?

[David]: It’s a question which, today, has no answer.

Although authorities warn of the danger, since the first sightings were reported in the mid-2000s, tourism has increased in the area near Nápoles Park. And that, of course, brings money.

Today the town of Doradal even has statues of hippos. Tours are offered to see them in the rivers with their young, and the shops sell souvenirs in the shape of these animals. Some even find them to be cute pets.

This is a video that made the news in August 2020:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Fisherman 3]: Dudes, see what we caught, see, a baby hippopotamus. See . . . stand it up, stand it up.

[Fisherman 1]: Hey, how cute, buddy.

[Fisherman 2]: Hey, so cute, dude, so little.

[David]: It’s a baby, of course. In the video, two fishermen on the Magdalena River are seen holding it, while a third is filming. It’s as tall as a small dog, and they grab its head and make it look at the camera.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Fisherman 3]: Tiny, see, we caught it . . .

[Fisherman 2]: But make it walk alone, to see it. Make it walk, to see it . . .

[David]: They begin to pat its body to get it to walk. The animal resists and tries to lie down on the ground. Then one of the fishermen pulls a rope that he has tied around its neck, as if it were a dog.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Fisherman 2]: Look at that beautiful hippo. A hippo, a tiny hippo, the baby of a pig . . .

[David]: No one really knows what happened to that hippopotamus, but one media outlet said that, after keeping it as a pet for several days, the fishermen released it into the river.

If everything remains as it is now, one day it will be one of those 1,400.

[Daniel Alarcón]: In September 2020, a Colombian court accepted a lawsuit from a legal expert in animal rights, who wants to keep culling from being the solution to the problem. A judge decided to bring all the parties involved together to resolve the situation once and for all.

If they can reach an agreement at that meeting, the judge will define the matter based on that. If there’s no agreement, it will be the judge himself who decides the future of hippos in Colombia.

In April 2021, a herd of hippos established outside the Nápoles Park was reported for the first time, in a nearby lake.

They are believed to number five so far.

David Trujillo is a producer for Radio Ambulante. He lives in Bogotá.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Nicolás Alonso, and by me. Désirée Yépez did the fact-checking. The music and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri.

Special thanks to Caracol Radio for sharing a large part of the archives you heard in this episode.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Aneris Casassus, Xochitl Fabián, Fernanda Guzmán, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Rémy Lozano, Jorge Ramis, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Emilia Erbetta is our editorial intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Studios, and it’s produced and mixed on the program Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.