Mud Man | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

We are in mid-1974 in the port of Veracruz, Mexico. It is swelteringly hot in the Allende Prison, an old, run-down jail.

[Mario Navarrete]: It’s not the most charming place. It’s a place with police, with people going in and out, noise.

[Daniel]: That is archaeologist Mario Navarrete. He has just come from Xalapa, the state capital two hours away. When he enters the prison, a man leads him into a room. And Mario sees the reason that brought him here: a dirty cardboard box, and inside, a heap of pottery shards.

[Mario]: The archaeological pieces that we have so much respect for and handle with gloves—and those things are lying there in a cardboard box, and they have rubbish on top because someone thought it was a dump and they threw a soda bottle in there. So suddenly it does feel confusing and makes you ask, “Now, what is this?”

[Daniel]: What he is seeing has a name: tepalcates. A Mexican word of Nahuatl origin that means just that: pieces of pottery. Mario begins to observe them. Some of the fragments are a natural color.

[Mario]: That brown color. I am made of clay. Like this, half burned, charred.

[Daniel]: Others are a pink color; others are painted with lime.

Mario tries to organize what he sees. That’s why he’s at the prison—as an archaeology expert to give his expert opinion. The prosecutor’s office suspects that those shards of pottery are fragments of various pre-Hispanic figures and has arrested a man accused of trafficking in them. This is a federal crime punishable by up to ten years in jail. That’s how it was in the 70s, and it is to this day.

What Mario must do is give his verdict. In other words, are these pieces that he sees the remains of figures made centuries ago? Or are they just pieces of contemporary craft? It may sound easy, but it is not, because in Mexico, a country rich in archeology, looters, traffickers and counterfeiters of ancient pieces abound. Very skilled people, capable of disrupting the country’s heritage and also causing chaos in museums like the one where Mario works, the Xalapa Museum of Anthropology, also known as the MAX.

[Mario]: An anthropology museum like the one in Xalapa has among its staff archaeologists who are supposed to be able to identify fake pieces and original ones.

[Daniel]: The problem is that determining with absolute certainty how old a piece of pottery is can be very difficult. There are various scientific methods, from thermo-luminescence to radiocarbon dating, but none are 100% foolproof.

[Mario]: The thing is that archeology is not an exact science.

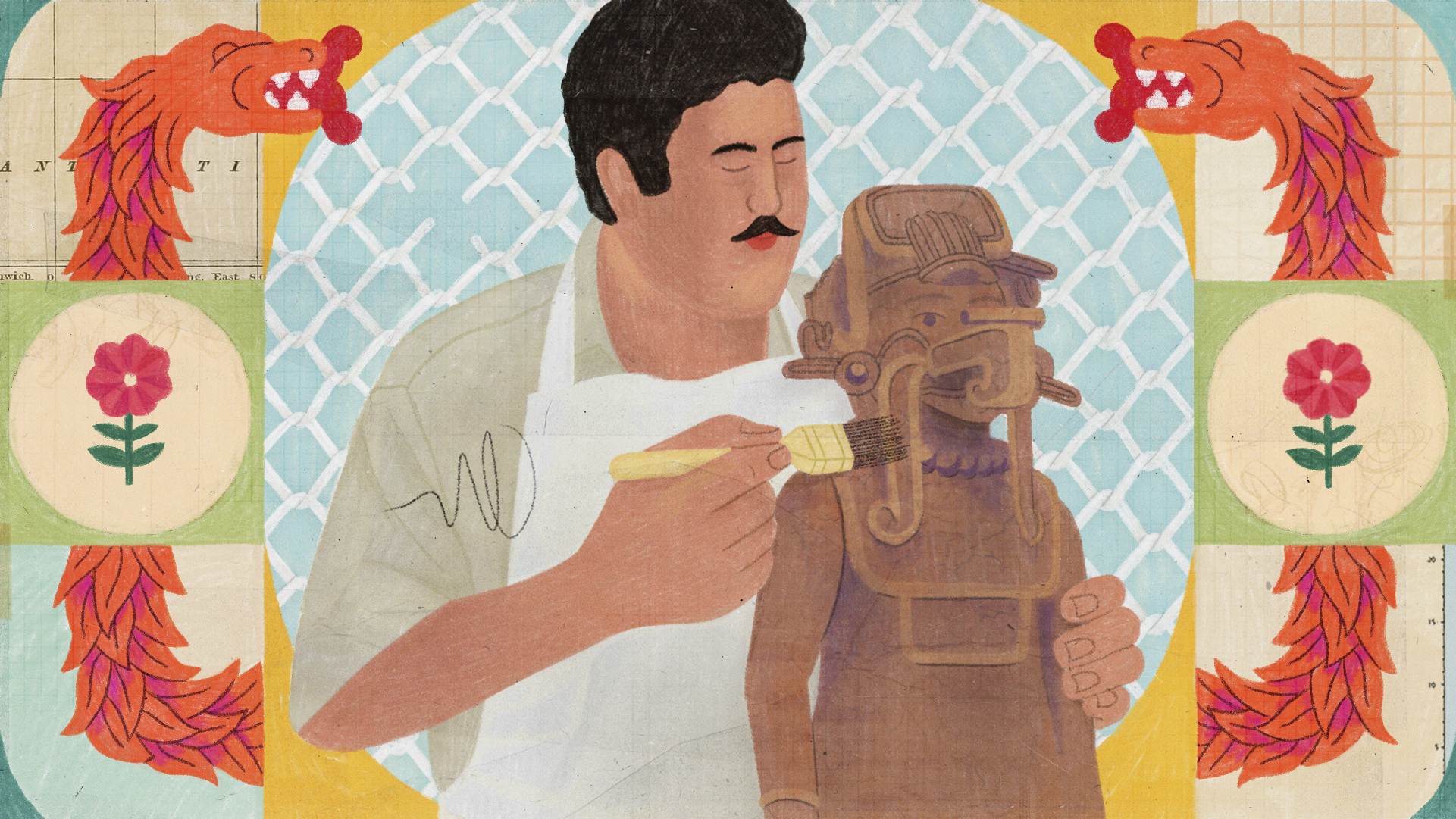

[Daniel]: Distinguishing at a glance between an original piece and one made by a talented counterfeiter is something learned with practice. It doesn’t even consist of visual work, but rather tactile, where one spends hours and hours with figures in their hands, just as Mario had been doing for almost 10 years, in the MAX warehouse. There, in silence, with his eyes closed, he has often felt their textures and shapes between his fingers. The task is almost spiritual.

[Mario]: You cannot imagine the feeling of touching an original piece. With your bare hands, right? And feeling it, and feeling that texture which is sandy, which is smooth, which is painted. You feel the beauty of the human features—a cheek, an eye, an ear, a neck, an ornament, a headdress, some scales, some fangs.

[Daniel]: And using the same approach he has had with the treasures of the museum, Mario now examines those fragments in the Allende prison.

[Mario]: You touch them there, people are coming in shouting and everything. And you are carried away for a moment and say, “I’m not in the prosecutor’s office, I’m not in a prison, I’m not anywhere. I am on a trip to a past where there was art.”

[Daniel]: As he touches those tepalcates, he notices that some feel old, sandy. Maybe they are original. But other parts…

[Mario]: They seem new… How can this be?

[Daniel]: Mario suspects that someone has tried to rebuild several original pre-Hispanic figures using these pottery pieces to replace the missing parts with new ones. It is like having before him the jumbled parts of different picture puzzles—with the added detail that some seem to be from over a thousand years ago, and others from the last decades. In other words, chaos.

Mario wants to express his doubts. But at the Allende prison, that’s not what the experts are expected to do.

[Mario]: You cannot talk at length, speaking as if it were a technical thing. You just have to say yes or no; there is no room for ambiguity.

[Daniel]: You just have to answer this question: Are the pieces original, that is, pre-Hispanic?

If he says, “Yes, they are original,” then they belong to the archaeological heritage of Mexico, and the defendant could face up to ten years in prison.

If he says, “No, they are not original,” the pieces will become the remains of mere contemporary crafts and the man will be free to go. Mario makes a decision:

[Mario]: “Yes, they are original.” And that’s the end of it.

[Daniel]: The man is found guilty. Mario returns to Xalapa and thinks no more about the matter. He has done his job. But a few days later, he receives a letter with a photograph. Brígido Lara, the defendant, has evidence that he is innocent.

We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Journalist Paul Antoine Matos and our producer Pablo Argüelles traveled from Mexico City to Xalapa to report this story. Paul picks up the story.

[Paul Antoine Matos]: We went to Xalapa because we wanted to meet Brígido Lara, the man accused of trafficking in archaeological pieces in 1974.

[Brígido Lara]: How are you?

[Paul Antoine]: Nice to meet you, Brígido, how are you?

[Brígido]: The pleasure is mine. I’m fine, I’m fine.

[Pablo Argüelles]: Hello, Mr. Brígido, how are you?

[Brígido]: Fine, fine. Well, here I am.

[Paul Antoine]: We met him one cloudy morning in May of this year, 2023, in the northern part of the city. Today, Brígido is 82 years old, and sometimes his voice shakes a little. But from the beginning, he was very confident and easygoing with us. It seemed evident that he had told his story many times and that he was used to being interviewed. When we sat down to talk, the first thing he did was show us a big album where he has kept news articles over the years. All about him.

[Brígido]: Here I have several newspapers. Some good and others bad, because they have also attacked me a lot.

[Paul]: So can we check them out in a bit?

[Paul Antoine]: Before telling us about how he got to jail and about the photograph he sent to archaeology expert Mario Navarrete, Brígido told us about his childhood on a ranch in La Mixtequilla, a region in the state of Veracruz, very close to the Gulf of Mexico.

[Brígido]: In that region you can find remains of different types, be it pots, bowls, a plate or a fragment of a figure, or like a human being, a bird, or an insect.

[Paul Antoine]: Ceramic remains from two pre-Columbian civilizations: the Olmec and the Totonac. In the 40s, when Brígido was a child and found those fragments, he was very impressed. But very little was known about its creators, the people of those cultures. Everyone called the pieces simply “idols” or tepalcates. And hardly anyone was interested in them. Brígido, on the other hand, was already playing and making his first figures at the age of eight with clay he found in the streams.

[Brígido]: I started modeling animals and everything we had in the house, like dogs, pigs, donkeys. I had many failures. I had many, many failures.

[Paul Antoine]: What happens is that clay is very fragile and fickle. In addition, turning it into pieces that stand the test of time was an art that Brígido had to learn on his own. Because at first, when it rained, his figures fell apart. That was something he could not understand: How had the pre-Hispanic creators managed to make their pieces so resistant? Brígido found the answer by carefully observing nature.

[Brígido]: That part also gave me a lot of wisdom, mind you, because I am very analytical. And if something happens to me on one side, I have to study and figure out why that happened to me.

[Paul Antoine]: He realized that every time they renewed the field at the ranch by burning it, the clay shelters of insects called rosquillas were left intact.

[Brígido]: They were left very smooth, all the walls smooth, the little hole where they had lived…

[Paul Antoine]: And then, when it rained…

[Brígido]: You found the shelters full of water. Those little containers where the rosquilla slept—full of water. It was wonderful.

[Paul Antoine]: That’s how he understood that he had to bake his pieces. By the mid-50s, when he was a teenager, Brígido had a very rudimentary workshop in his town and was capable of copying the Totonac and Olmec figures found in the ruins, fields, and streams. But he also invented things out of his own imagination, inspired by the originals. And the more talented he became, the more his fame grew throughout Mixtequilla.

[Brígido]: And word got around. And all of a sudden, there were a lot of people—Gringos, Italians or Spaniards.

[Paul Antoine]: People who bought his figures. And they paid him well: 10 or even 100 times more money than what he earned harvesting in the fields.

[Brígido]: When I turned 16, 17 years old, well, I already knew that my things had a certain value, right? And you want to have money, and money, and more money, and more money, you know?

[Paul Antoine]: And if it was a question of making money, you could say that Brígido was in the right place at the right time.

[News reel]: From every country people come to Mexico. By air, by train and by highway…

[Paul Antoine]: This is a promotional film about Mexico, made by a US company in the 1950s. Right around that time, the Mexican government began to promote tourism in the country. And travelers from all over the world became increasingly interested in the cultures of ancient Mexico.

[News reel]: What mysterious ceremonies? What solemn processions occurred here?

[Paul Antoine]: And in the mysteries of its archaeological zones, from Monte Albán to Teotihuacán. And so, foreign artists, politicians and collectors started coming to Mexico, and many took the opportunity to take back a pre-Hispanic piece in their suitcases.

And it was not so difficult to get archaeological pieces at the time. The laws for the protection of heritage in Mexico had several ambiguities that made them hard to enforce, and private collecting was also allowed. All of which made the market for pre-Hispanic figures a very wild world, full of deceit, scams, and bribing of authorities.

That market generally worked like this: Buyers and collectors from around the world hired local middlemen to find pieces throughout the region.

And these intermediaries did not have a lot of scruples. The pieces were found in real archaeological excavations, but also in sites that had been filled with figures bought from local artisans. Craftsmen like Brígido. He would sell his own creations to middlemen, and also charge them for restoring and completing broken original pieces.

But by 1972, when Brígido was 31, the rules in Mexico had changed. That year, the government enacted the Federal Law of Monuments and Archaeological Zones, which is still in force today. It was much stricter. For one thing, private collecting would be much more regulated: everyone who already had archaeological pieces would have to register them with the authorities. The law also prohibited exportation of pieces, as well as their transportation, and especially their reproduction without commercial permits.

All of which leads us to the very particular case of Brígido and the place he occupied in that deceptive market for handicrafts and pre-Hispanic pieces. When we asked him how he viewed his business in those years, he told us:

[Brígido]: Well, the truth, well, look, this did not matter to me, because there were many things I did not know. Many people were careful because it was a crime, which I did not know—wow, how big or why it was even a crime. And, for example, looting is a crime prohibited by our laws. But if I made a piece, why was it a crime?

[Paul Antoine]: It is impossible to confirm what Brígido knew or did not know about the laws in the 50s or 70s, but what we do know is that he saw no problem in selling figures inspired by pre-Hispanic pieces… According to him, he never passed off his creations as original pre-Hispanic works, which would be fraud and forgery. Following the logic of his story—which we remind you happened a long time ago and is very difficult to verify today—those who committed the deception were the middlemen, if they decided to resell their pieces for hundreds of thousands of dollars to foreign museums and collectors.

At that time, he was a young man who wasn’t worried about the law, but about making money. Brígido did not even sign the pieces, nor did he find out whom the intermediaries sold them to, or for how much. Once they left his workshop, he would wash his hands, move on to the next one, and that was that. He worked this way for almost two decades.

Until 1974, when his luck changed. In the middle of that year, he heard a story on the radio. Two men had been arrested for trafficking in archaeological pieces. They were in the Allende prison, where we began this episode, that jail in the port of Veracruz.

[Brígido]: The news spread like wildfire among all the neighbors and friends. “Hey Brígido, so-and-so has been caught, so-and-so has been arrested,” and so on.

[Paul Antoine]: In this case, so-and-so were two of his cousins who sometimes sold his pieces. They were arrested with a box full of clay fragments and accused of trafficking in archaeological pieces. After the arrest, the neighbors began to talk about Brígido, calling him a looter and smuggler of pre-Hispanic pieces.

So he decided to go to the Allende prison. He wanted to clarify the situation. At the prison, Brígido explained to some police officers that his cousins were being charged with the crime of trafficking in pottery pieces, but later he told them:

[Brígido]: “I made those pieces.” I took on all the responsibility.

[Paul Antoine]: The pieces were crafts made by him. The officers warned him that he would have to verify that what he said was true. Brígido agreed and exchanged places with his cousins, who were released. He thought he would be in jail for a few days, until his innocence was proven. But things did not go as he expected.

[Brígido]: No, first I spent 20 days locked up. And there were more than 230 people in that space, and after 20 days I was sleepwalking.

[Paul Antoine]: He was beginning to regret having gone to prison, and little by little his hope of getting out was fading. He did not know how to begin defending himself against the accusations, and very soon he found out that he could get 3 to 10 years in prison. But his lawyer came up with a plan to prove that Brígido was the creator of the pieces: bring clay to the prison so that he could make a figure from scratch. So in secret, without the permission of the prison director, they sent a van to Brígido’s town… about 40 kilometers from there. They got two clay sacks and returned to Veracruz.

[Brígido]: The clay arrived at six in the afternoon.

[Paul Antoine]: OK.

[Brígido]: And early the next day, at—I woke up, took a bath, and on one of the tables there…

[Paul Antoine]: Mhmm…

[Brígido]: There I began to model the piece. And there were about two or three who were watching how I was handling the clay, right?

[Paul Antoine]: They were guards, right?

[Brígido]: No, they were prisoners, too…

[Paul Antoine]: Oh, they were prisoners…

[Brígido]: They were in the same area where I was.

[Paul Antoine]: Hours passed. Brígido continued to shape the clay before his small audience. Until one of his companions, looking worried, told him that the prison director was coming. And when he arrived, he stopped next to Brígido, and said to him:

[Brígido]: “Knowing what your situation is,” he says, “are you now making pieces inside the prison?” And I stood up, firmly because, well, that’s how I am, very spontaneous, right? Now I thought whatever came to me. I tell him, “Heck, Mr. Director,” I said, “I’m already in jail; I don’t think they’re going to kill me because I’m making the pieces here.” He didn’t answer anything. And he left. And I go back to my clay.

[Paul Antoine]: The director left him alone. And so, a day later, the sculpture was ready. It was a seated woman, about five feet tall. She was inspired by a Totonac figure named Cihuateteo, a woman who has died during childbirth. The lawyer sent a photo of the piece to Mario Navarrete, the archaeology expert we heard from at the beginning of this story.

[Mario]: I never went there with the desire to say, “Put him in the deepest part of the dungeon.” No, no, no, no. My job was very simple: Tell me whether this is an original or a fake. Well, I just said what I thought: “Yes, they are original.”

[Paul Antoine]: But now, with a photo in hand, Mario wavered… The letter explained that Brígido had made that piece, seemingly Totonac, in prison. In other words, perhaps Brígido was not a dealer, but someone with a talent for making his own clay figures. An artist.

[Mario]: The issue at hand was not to discuss at that time whether it was a work of art or not. The issue was to reverse a wrong opinion.

[Paul Antoine]: So, after consulting with his boss, the director of the MAX, Mario acknowledged that the tepalcates he had touched at the Allende prison were not, as he had believed, a mixture of pre-Hispanic and modern, but all from Brígido.

Days later, a judge signed Brígido’s release. And shortly before leaving in January, 1975, when many people already knew how talented he was, when even the local press began to write about him, he received two invitations.

The first was from the director of the Xalapa Museum of Anthropology, a man named Alfonso Medellín and an eminent figure in Mexican archaeology. He wanted Brígido to visit him so that he could make him a job offer.

The second was from some smugglers he had met in jail.

[Brígido]: They had offered me to take me to the United States just to take the clay; I would make the pieces there.

[Paul Antoine]: They offered to take him across the border. Set up a workshop for him and bring him the clay from his land so that he could work full time making fake pieces, which they could sell for thousands of dollars to collectors and museums.

Brígido had to make a decision between two opposite ways of continuing to apply his talent with clay.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Before the break, Brígido received two job offers inviting him to go down very different paths. One would take him to one of the most important museums in Mexico; the other, to falsify archaeological pieces in the United States. Now he had to decide. Our producer Pablo Argüelles continues the story.

[Pablo]: A few days before his release, Brígido received a visit from a friend who asked him:

[Brígido]: “So, what are you going to do? Are you going to accept the director’s invitation?” I tell him, “Well, I’m not.” “What do you mean? But why not?” I say, “What am I going to do there? And how am I going to support myself there?” I didn’t know any museums, I didn’t know archaeologists, anthropologists, I didn’t know Xalapa. “Hey,” he says, “well, if they’re inviting you… I’ll take you.”

[Pablo]: The friend persuaded him. So, shortly afterwards, Brígido met in Xalapa with the director of the MAX, Alfonso Medellín.

[Brígido]: And he says to me, “Look Brígido,” he says, “I am very interested in you collaborating with us and hopefully being a part of our team.”

[Pablo]: But first he needed to show his skills. The director told him that a very important archaeological zone had just been discovered in a part of the state called El Zapotal. There, a very rare sculpture had been found: a seated skeleton, with a large headdress and a skull-like face sticking out its tongue at onlookers. The Totonac god of death, Mictlantecuhtli. And the MAX needed a copy.

[Brígido]: That was the professional test that Professor Medellín gave me. Five people from the restoration department of Mexico had come three times, wanting to make a copy because that piece cannot be moved since it is made of raw clay. And if you put any pressure on it, it fragments.

[Pablo]: In other words, it breaks apart. It was a very difficult challenge. But Brígido accepted it and the director asked him:

[Brígido]: “How are you going to do the work? Are you going to get a mold, or how are you going to do it?” he said. “No, man,” I said, “this piece is modeled, but it is not to be molded.” He was still, then he leaned back a bit. “So, how are you going to do it, Brígido?”

[Pablo]: Brígido replied that he was going to sculpt a copy by sight, with his own hands, just as the original creators had done. The director was excited.

[Brígido]: He slammed the desk like this. And he tells me, “Go ahead, Brígido.”

[Pablo]: Brígido worked in Zapotal for five months, sculpting and sculpting at the archaeological site, in front of the god Mictlantecuhtli, until he managed to replicate it. And he did it not only once, but he made three copies of different sizes. Test passed.

Brígido joined the MAX as a restorer in 1975. It was a great achievement. But to work there, he had to pay quite a high price.

[Brígido]: When I come here, they take away my inspiration to do my own work. And from there they got me, saying, “I want a reproduction of this, I want a copy of this, a copy of that, a copy.” Just reproductions.

[Pablo]: Just figures for the museum shop, all with an official seal that identified them as replicas. And so the years passed…

In 1985, a decade after Brígido joined the museum, the governor of Veracruz announced that he would rebuild and expand the MAX.

Remodeling it was necessary. The old building had leaks, and in a city as rainy as Xalapa, people had to enter with umbrellas to see the works. But the project also held more personal reasons for the governor. He was an archeology fan and wanted to show off Veracruz’s Mesoamerican identity to the whole world. And to do so, he spared no expense.

First, he commissioned the construction of the new building by an American firm. Second, he ordered the mayors of the different municipalities of Veracruz to send archaeological pieces from their regions to the MAX. And this, remember, was illegal. And third, he went shopping abroad, and not exactly for new clothes. He went to very prestigious auction houses, like Sotheby’s, for pieces from the cultures that had lived in the state of Veracruz. And so, many new figures began to arrive at the MAX. One day, a few months before the museum opened, Brígido was working when one of the janitors came to see him.

[Brígido]: He tells me, um, “Hey, man, wow… some fantastic pieces came in yesterday. If you want, let’s go so you can see them.”

[Pablo]: Brígido accompanied the janitor to see the pieces recently arrived from the United States. Several of them were already out of their packaging. And indeed, they were a marvel, wonderful. There was an eagle warrior, a seated figure, a god known as Xipe Totec…

[Brígido]: When I see them, I was like… I say, “Whoa…”

[Pablo]: Whoa… He was sure they were his.

But… when you saw the pieces, how did you recognize them? How did you know they were yours?

[Brígido]: Well, hey, you know what you make. I have all of that here. Inside my mind and my memory. Everything, every single thing.

[Pablo]: But that day, when he saw them, he kept it to himself.

[Brígido]: I didn’t know whether to tell the director or not.

[Pablo]: A day passed, another passed. And he kept on wavering… Because… actually… no one had to find out. Brígido’s figures could pass for originals. It could be a secret between him and the pieces.

[Brígido]: Gosh, what should I do, what should I do, and how… But one day a decisive thought came to me—I had to say something.

[Pablo]: So he talked to one of his mentors at the MAX, and when the museum director found out…

[Brígido]: He never mentioned anything to me. And all the archaeologists… Nobody mentioned anything.

[Pablo]: Brígido’s pieces were kept in the museum’s warehouse. The subject remained secret, until the new MAX was inaugurated a few months later, in October 1986. There were illustrious guests, including the President of Mexico. And this man was also there:

[Eugenio Logan Wagner]: My name is Eugenio Logan Wagner.

[Pablo]: Eugenio is a Mexican-American architect living in Texas. In the 1980s, he did freelance journalism with a colleague named Mimi Crossley. They wrote on archeology for outlets like the Washington Post and the New York Times. Mimi and Eugenio traveled from the United States to Xalapa to cover the opening of the museum. And there, the new director —Medellín had just died—told them about Brígido.

[Eugenio]: Listen, the restorer of the ceramics used to do his own work, and they thought he was looting and he got arrested.

[Pablo]: It was a quick chat. But intriguing enough for Eugenio to not forget it. Back in the States, he and Mimi began looking for media outlets who would publish something about the MAX’s opening. They thought of Connoisseur magazine, specialized in fine arts and collecting. The magazine’s editor had been director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum, the Met, for nearly a decade.

[Eugenio]: And he loves those semi-scandals in the art world. And as soon as we mentioned the Brígido Lara thing to him, he hired us on the spot. “You know what? We’re going to do an article on him.”

[Pablo]: So Eugenio and Mimi went back to Mexico and looked up Brígido. They spent several days with him and even went to his town. They asked him about his methods…

[Eugenio]: And he told us about his techniques to make the piece look old. Sometimes he would pour Coca Cola on it, sometimes urine, whatever; he had his own exotic formulas.

[Pablo]: And they also learned more about his style by watching him work.

[Eugenio]: We could start to identify the way he made hands, for example. He has a certain a style, that you can tell, “Oh, that’s a Brígido!”

[Pablo]: By the very fine and detailed fingers. Eugenio and Mimi spent about six months researching and traveling. They would review catalogs from different museums around the world, then they would return to Xalapa and show the images to Brígido.

[Eugenio]: “This one is yours, yes or no?”

[Pablo]: The one at the St. Louis Museum in Missouri?

[Brígido]: “Yes, indeed.”

[Pablo]: “And the Ehecatl, that is to say the God of the Wind in the Metropolitan Museum of New York?”

[Brígido]: “Yes, that’s right.”

[Pablo]: “And what about the ones in the Dallas Museum of Art?”

[Brígido]: “I made them.”

[Pablo]: Before publishing the article, the journalists contacted the Met, the St. Louis Museum and the Dallas Museum. They wanted to tell them what they had investigated and give them the chance to comment. Neither the Met nor St. Louis responded immediately. But the Dallas Museum of Art did.

[Eugenio]: And they immediately said, “Oh, really? Well, let’s test them to see what dates we get.”

[Pablo]: The results of the thermo-luminescence tests showed that the three pieces in the museum had not been made between the years 600 and 900 AD, as was believed, but were contemporary. And so, in March of 1987, the director of the Dallas museum went with a curator to Xalapa. Brígido recalls that he was just entering the MAX office when they called out to him and approached. He says they were very excited…

[Brígido]: And putting their hands into their backpacks, taking out folders where they brought the photos, and word had supposedly reached them that I said those pieces were fake. And it was the complaint they came to make.

[Pablo]: They wanted Brígido to show them that the three pieces they had in Texas were really his.

Brígido took them to the MAX warehouse, where many of the replicas he had made were kept, the ones that came with the reconstruction of the museum. And there he showed the Texans some figures:

[Brígido]: Oh wow, when these men saw them, they didn’t know what to do.

[Pablo]: They didn’t know what to do: they were very similar to the three they had in Dallas.

The director and the curator returned to the United States, convinced that their pieces were by Brígido. And at the end of April, the St. Louis and Dallas museums announced that Brígido claimed to be the creator of several pieces in their collections and that the scientific analyses being carried out were already showing that some actually were modern.

Overnight, several newspapers in the United States replicated the news. It was a real shock to the art world. For one thing, because the Mesoamerican art collections in some of the most important museums in the world could lose their value by hundreds of thousands of dollars. But also because it shook the knowledge that until then was believed about the ceramics of the pre-Hispanic cultures of Veracruz. Suddenly a piece that was believed to be in the Totonac style became a Brígido Lara.

After all the research they did, Eugenio and Mimi believed Brígido. That is to say, that their pieces were made by him.

[Eugenio]: And they weren’t copies, that is, replicas. They were pieces inspired by pre-Hispanic art, but he had made his own creations.

[Pablo]: Brígido told Eugenio, Mimi and other journalists the same thing he told us: that he never passed off his creations as pre-Hispanic pieces. In Eugenio’s mind, he did not commit any crime.

Further, the news also exposed the ways museums and collectors had acquired Mexican pieces for decades. Finally, in June 1987, Eugenio and Mimi’s article was published in Connoisseur, and Eugenio began getting calls from private collectors telling him…

[Eugenio]: “Listen, I think I have a piece by Brígido Lara.”

[Pablo]: Suddenly, Brígido went from being an anonymous artisan from a small town to an artist. An artist who had put some of the most important and powerful museums in the world in check. And so he lived his fame for years, saying that his work had been exhibited at the Met, selling certified clay figures, and also doing restorations and appraisals for the MAX. And when the pandemic hit, he retired.

One day before Paul and I returned from Xalapa to Mexico City, Brígido invited us to his workshop…

[Brígido]: Hello, hello!

[Pablo]: Hello Brígido!

[Brígido]: Come in, come in, how are you?

[Paul Antoine]: How are you? …

[Pablo]: There he began to show us all his tools. In the middle of the room was a large concrete table where he made his figures. And in one corner were three large containers filled with raw clay brought from the streams of his hometown.

[Pablo]: How long has this clay been aging like this?

[Brígido]: Over twenty years…

[Pablo]: This is the clay from over 20 years ago…

[Brígido]: Yes, more than 20 years.

[Pablo]: He taught us that good clay is like a good wine.

[Brígido]: You take this piece of clay like this…

[Pablo]: Each one has its own aroma, its own elasticity, and also its own texture.

At last, we were able to see how the clay was molded to his will.

[Brígido]: With this clay I can do whatever I want. Any piece from any culture.

[Pablo]: Being in the workshop helped us make sense of much of what we already knew about Brígido. Before going to Xalapa, we read old newspapers, watched movies and also talked with his acquaintances. Most of these were very light conversations, like “Brígido is very kind, he is very talented”. But one of those people also told us something that we found more intriguing: that in Santiago de Chile, the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art has a Mexican piece. And that, judging by its appearance and its style, that piece might have been by Brígido.

Paul and I looked up the piece in the museum’s online catalog. There, it is titled Xipe Totec. It is a clay man about 1 meter tall. On his face he has a mask and on the rest of his body, a skirt and the skin of another creature. When we saw it, what caught our attention the most was how fine his feet and hands were… Because, as Eugenio and other people we spoke to had told us, Brígido has an obsession about making very detailed hands and feet. And for that reason, that day in the workshop, as Brígido took pieces and more pieces out of a huge wooden crate and showed them to us…

[Brígido]: What do you think?

[Paul Antoine]: Look at that!

[Brígido]: These are hands…

[Pablo]: Paul and I immediately glanced at each other. Brígido had just removed from the box some clay hands very similar to the ones on the Chilean piece. So much alike that it made Paul almost shout. I think at that moment we both felt that perhaps we were about to unmask yet another Brígido piece, one that had managed to survive the big revelation of the 1980s. So Paul took out his cell phone and showed Brígido the photo we had of the piece.

[Paul Antoine]: Brígido, I wanted to ask you about these hands.

[Brígido]: Uh huh.

[Pablo]: He looked at the photo. And when Paul asked him whether he recognized the piece, he told us he did.

[Paul Antoine]: How can you tell it’s yours?

[Brígido]: Well, it’s that, the… now I know that can identify my work anywhere, because I always tell you that, like your handwriting, your handwriting, you can tell it apart from others here and in China, and at any time.

[Pablo]: In other words, the same thing that he had told us before. That a person always recognizes their own work. I pressed him…

[Pablo]: This image that you were looking at, could you say that you are 100 percent sure that it is by you?

[Brígido]: Yes, of course.

[Pablo]: With great pride he assured us that that clay man, the one that was in Chile, was his own.

That afternoon we said goodbye to Brígido. And back in Mexico City, we wanted to investigate some more…

[Alfredo Delgado]: Hello.

[Pablo]: Hello, Doctor. This is Pablo Argüelles, the journalist from Radio Ambulante.

[Alfredo]: Uh huh, how can I help you?

[Pablo]: We called Alfredo Delgado, current director of the MAX. He knows Brígido well and also worked as an archaeology expert witness for many years. We wanted to talk to him before calling the museum in Chile so that he could analyze the piece with us. We mailed him pictures and looked at them together on the phone. Alfredo didn’t take long to tell us that the clay man didn’t seem pre-Hispanic to him, but instead modern.

[Alfredo]: Yes, totally fake.

[Pablo]: According to him, the composition of the figure made no sense; it was a mixture of styles from different times and cultures: The head looked Aztec, the Mayan skirt and the mask… like that of El Santo, a Mexican wrestling and cinema hero. In other words, the clay man was like a “greatest hits of Mesoamerican figures” combined with 20th-century Mexican popular culture. Alfredo told us that whoever made the piece was a good craftsman. But he also said that he didn’t think it was by Brígido:

[Alfredo]: I definitely think it is not by Maestro Brígido.

[Pablo]: What makes you say that?

[Alfredo]: It is not Brígido’s style, neither in the firing nor in the finish nor in the proportions. If Brígido had made it, I think he would have taken more care of the details in order to make it look more pre-Hispanic so that there would be no doubts about its authenticity.

[Pablo]: Hmm! I am telling you because we showed it to him twice, and he told us it was 100 percent his.

[Alfredo]: Look, there are original pieces that the maestro claims as his…

[Pablo]: Oh, really?

[Alfredo]: Yes… And which we know came from excavations. And he may say, “Oh, I did that one.” He has so much production that he doesn’t even remember.

[Pablo]: And sure enough, Brígido made hundreds—if not thousands—of pieces between the 50s and 60s. It is probable that sometimes he confuses those that passed through his hands with ones he never touched. But it is also possible that he wants to attribute other people’s work to himself. In Alfredo’s view, Brígido may also want to shape his story to suit himself.

[Alfredo]: Brígido wants to pretend that he made handicrafts and didn’t know what he was selling; that the problem of their being passed for originals was not his, but that of the traffickers. But no: he did know what he was doing. Of course he knew…

[Pablo]: What you are telling me is interesting because, talking to Brígido, he just told us that he did not know…

[Alfredo]: Well… so, he wants to create his own myth, of course he does. I love the maestro very much, of course, but I have other information.

[Pablo]: And Alfredo told us that, before coming to the MAX, Brígido did work with another counterfeiter in Veracruz, and reminded us that, when other counterfeiters were caught, it was common for them to say that the pieces were their own creations—just popular artwork. Just as Brígido did when he came forward at the Allende prison in 1974. In this regard, Brígido told us that he did not know about this type of trick and denied having worked with other counterfeiters.

While he was telling us this, Alfredo continued to observe the clay man in the Chilean museum. At one point, he began to enlarge the images to observe the details more closely… And then, after looking at the limbs of the clay man, he told us:

[Alfredo]: Look, maybe it is by Brígido, eh? I am going to tell you a secret that few know. In Brígido’s sculptures he has an obsession with feet and they are very well detailed.

[Pablo:] Hmm!

[Pablo]: Now Alfredo was hesitating—and we hung up the call quite disconcerted. He left us wondering not only whether the piece in Chile would be a Brígido or not, but also something bigger: that it can be monumentally difficult to distinguish an original figure from a fake.

In any case, we had Alfredo’s final suspicion, so we called another archaeologist at the MAX. He also looked at photos of the piece and agreed with Alfredo: It was not pre-Hispanic because it did not have coherence from a stylistic point of view. He went so far as to say that it did seem to have been made by Brígido.

With this information and these doubts, we decided it was time to contact the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art. She’s the person we talked to:

[Pilar Alliende Estévez]: I’m Pilar Alliende Estévez.

[Pablo]: Pilar is an archaeologist and in charge of the museum’s collections. We began by telling her the story of Brígido and our suspicions that the piece they had in the museum might not be original. Then she told us what she knew: The piece had arrived in Chile around the 1970s from the museum’s founder, an architect and collector from that country.

[Pilar]: He bought that piece at an auction in the United States. So the story also coincides a bit, doesn’t it?

[Pablo]: Because he bought it at auction, just as the governor of Veracruz had done with Brígido’s pieces. And with the figure came a dating certificate.

[Pilar]: It gives a very wide date. The date comes out between 650 AD and 1450. And it is on one foot and on the area of the head.

[Pablo]: In other words, the tests, done by a laboratory in the United States, were done only on the left foot and on the head. In 1981, the clay man became part of the first thousand works with which the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art opened, and it very soon became one of the most emblematic of the collection. And then, on March 5, 1985, during one of the worst earthquakes in recent Chilean history, it fell off its base and broke into 135 pieces.

[Pilar]: And it became clear that the arm—one of its arms—was fake.

[Pablo]: During the restorations of the piece, the experts realized that the left arm was filled with plaster, with a metal mesh. And they realized that, in reality, the whole man had been reconstructed before, in a very crude way, with wires to join some pieces on the inside and also with glue applied at very high temperatures, which prevented thermo-luminescence tests from being carried out later.

[Pilar]: The person who restored or put this together was someone interested in the external appearance, and the work was like what a conservator or restorer would do; the inside didn’t interest them at all.

[Pablo]: Pilar also told us that the museum restorers saw that the pieces of the clay man were a mix.

[Pilar]: You could see there were parts that were possibly original and the others, uh, additions.

[Pablo]: And then she clarified something for us:

[Pilar]: That is considered an authentic piece.

[Pablo]: And indeed, according to the principles of the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art, such a figure, restored, with a mix of ancient and contemporary parts, is still considered a heritage piece. And that’s why it’s still on display today. But Pilar was not closed to the possibility that the whole piece was made by Brígido either.

[Pilar]: If it’s a Brígido, which it could be, I don’t know, it would be a Brígido that broke and was restored.

[Pablo]: And that later came to an auction in the United States and was sold to the founder of the Chilean museum. It could be. For Pilar, the work of a museum is to investigate its collections…

[Pilar]: And it has to always be very transparent on that. But to declare a fake piece as such, you have to do many more analyses.

[Pablo]: Much more detailed scientific analyses that complement the assessments of archaeology experts. Pilar explained that there is neither a plan nor money to carry out a study like that. But she also said:

[Pilar]: Obviously I am going to pass this information along to the registry.

[Pablo]: So that the inventary files show that Brígido Lara, a Mexican, reproducer of Mesoamerican pre-Columbian pieces, claims to have made this piece. For now it will continue on display. It remains to be seen what they decide to do with it, whether to carry out the scientific analyses, remove it from the collection, add some explanatory text for visitors, or simply leave it as it is.

During our reporting, Paul and I repeated to ourselves over and over again what Mario Navarrete, the expert we heard at the beginning of this story, told us: Archeology is not an exact science. It was our reminder whenever we came across inconclusive scientific analyses, or when experts expressed concerns.

[Pablo]: But the truth is that… when we began to find out about the clay man in Chile, we became obsessed with knowing whether it was original or fake. We wanted a clear answer, no maybes. However, what we found was something different. A more complex clay man. A man whose story does not fully conform to the boundaries between the original and the fake, between the ancient and the contemporary.

Brígido’s works have been exhibited anonymously in some of the best museums in the world. And it is no longer crazy to think that some people who listen to us may some day find themselves in a museum, looking at a figure from the coast of Veracruz, classified as pre-Hispanic… But that figure, a clay man for example… could be Brígido’s.

An authentic… Brígido Lara.

[Daniel]: Brígido dreams of recovering some of his pieces scattered around the world and exhibiting them in a turtle-shaped museum that he wants to build in Tlalixcoyan, his hometown in Veracruz.

Our thanks to the Xalapa Museum of Anthropology and its director Alfredo for all the help they provided. Also to Pilar Alliende, the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art, Eugenio Logan Wagner, and Jesse Lerner.

Paul Antoine Matos is a Mexican journalist and fact-checker for Agence France-Presse. Pablo Argüelles is a producer for Radio Ambulante. Thanks to this episode they discovered that they are neighbors on the same street in Mexico City.

This episode was edited by Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music are by Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Nancy Martinez-Calhoun, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez , Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Ana Tuirán and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.