Where The Turtles Live | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

One day in 1991, Gerardo Chaves, a Costa Rican biologist specialized in reptiles—specifically, crocodiles—was walking along a beach in Costa Rica. It was night.

[Gerardo Chaves]: I was chasing my horse, that had left me stranded, and I tripped over something on the beach, and when I shone a light on it, I saw it was a turtle.

[Daniel]: Gerardo didn’t know much about these animals, just a little more than he had learned in college, but he was fascinated by what he saw. That turtle, big, heavy, slow, was going to make a nest in the middle of the sand, using its flippers, to deposit its eggs.

That lonely turtle encouraged him to do a research project on these animals at the university where he worked.

[Gerardo]: Nesting, parasites, that sort of thing.

[Daniel]: Their habitat, their anatomy, their behaviors… Two years passed in that task.

[Gerardo]: If I remember correctly, I had seen about 45 turtles out there. And I had looked after about 20,000 hatchlings, something like that. I had done estimates based on the nests and so on.

[Daniel]: In other words, he devoted his time to monitoring the nests to prevent predators from eating the eggs or even humans from stealing them…

So, when Gerardo first visited Ostional, a black sand beach on the Costa Rican Pacific Ocean, he felt that he had already seen many turtles. It was about 3 years after that first stumble. He was a professor’s assistant and went with several students. It was also at night, so it was easier to watch the turtles without disturbing them.

[Gerardo]: So. I stand on the beach and I say, “Students, look. This is a turtle beach. Don’t make any noise. You have to avoid lights. We are going to walk stealthily so as not to scare them, and we are going to get to where they are.” And as I turned around, I stepped on one and fell, and I fell right on top of another one.

[Daniel]: Gerardo had his flashlight off.

[Gerardo]: And then I turn on the flashlight and I see the whole beach is full of turtles, ha ha ha.

[Daniel]: Hundreds… maybe thousands. As far as the light allowed them to see. They were witnessing what is known as a mass arrival—periods of a few days when thousands of turtles come out of the sea to lay their eggs on the beach.

[Gerardo]: Some turtles are going up, while others have finished nesting and are going down. So you see turtles walking all over each other, then coming up often to nest in the same spot. So you see two or three turtles trying to dig a hole in the same spot.

[Daniel]: It’s a mess, says Gerardo. But a spectacular mess.

[Gerardo]: I think anyone who goes there and gets to see or be in the middle of a mass arrival feels that excitement. I’ve seen about 400 arrivals. It is still as impressive as it was the first time. It’s incredible.

[Daniel]: The thing is that Ostional is a special beach. It is the second most important in the world for nesting of olive ridley turtles. These are fairly small; they measure about 65 centimeters, and they are very heavy—from 30 to 50 kilograms.

Today they are in a vulnerable state and on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which classifies species in danger of extinction.

Mass arrivals occur almost every month at Ostional. Some are small—just a few thousand animals—and others can be up to hundreds of thousands. Everything takes place in a strip of beach between one and seven kilometers long.

[Gerardo]: We have detected up to 2,000 turtles coming up to the beach every ten minutes. Usually at night, but also often during the morning or sometimes throughout the day.

[Daniel]: Because of its importance, Ostional Beach is legally protected as a wildlife refuge. People have been living in the area since before the refuge was created, but human intervention in the ecosystem is quite restricted by law.

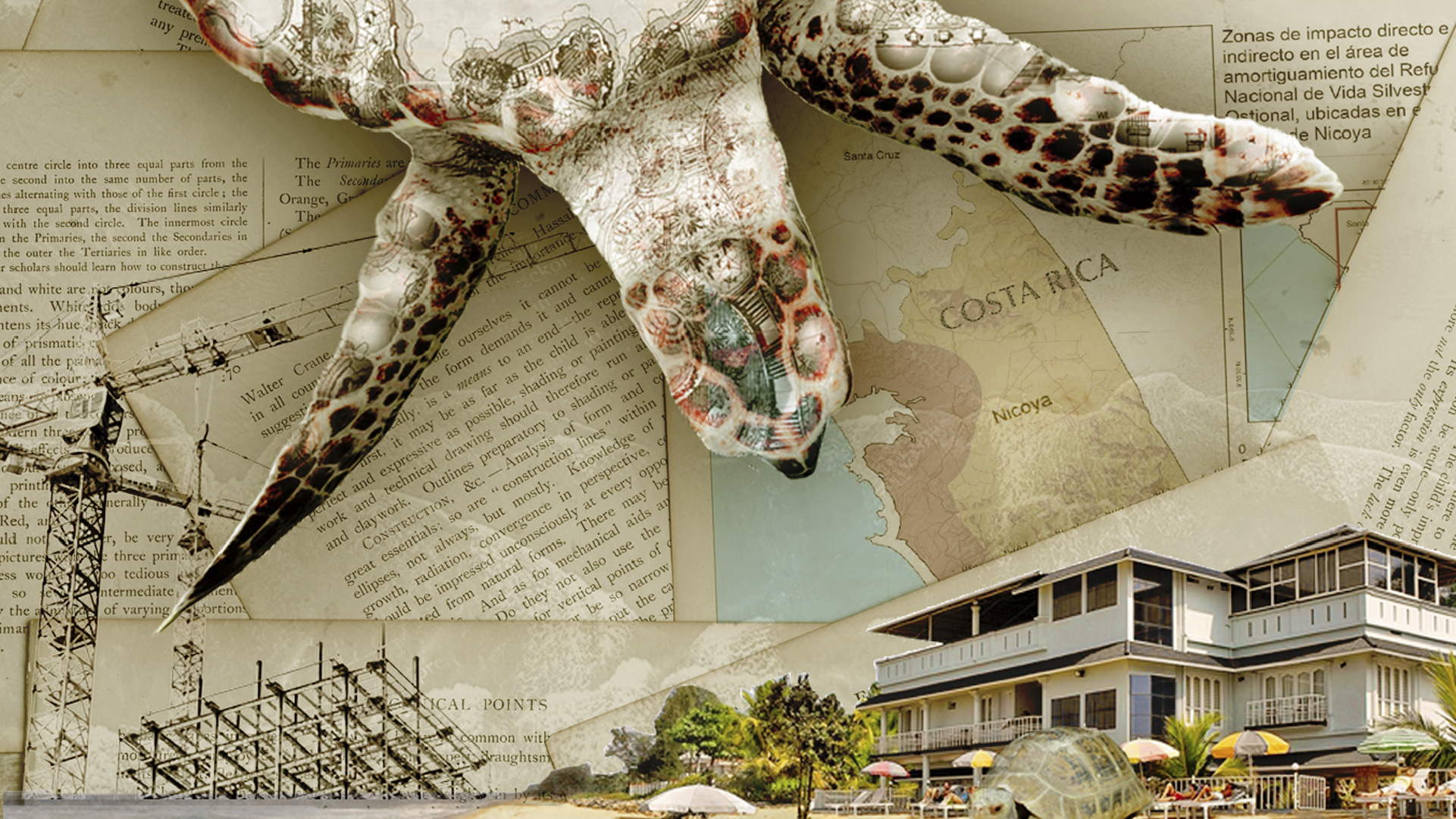

However, about 10 kilometers away, in a town called Nosara, things are very different. And this is the story of how the future of both places and of thousands of turtles are closely related.

We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back. Sociologist Arturo Silva reported this story along with our senior editor Luis Fernando Vargas.

Luis Fernando brings us the story.

[Luis Fernando Vargas]: The Ostional National Wildlife Refuge was founded and demarcated in 1983, mainly to protect the turtles’ nesting habitat.

[Gerardo]: This is really more a marine refuge than a land refuge. The only land area it includes is a strip of 200 meters in front of the sea and in the sea, if you proceed even more than a kilometer.

[Luis Fernando]: The first record of a massive turtle arrival on that beach is from November 1959, and scientists don’t really know why. It is not very clear how turtles choose their place to nest en masse. But the few inhabitants of Ostional soon learned to live with them.

[Gerardo]: The beach was cleaned up for the turtles so that they had more space to nest. Well, the initial idea was to have more eggs, more places for eggs. That favored the turtles.

[Luis Fernando]: And also the residents of Ostional, because more places with eggs meant more eggs for sale and consumption. Turtle eggs are a type of delicacy. They are even said to have aphrodisiac properties. Many people eat them raw and dig them up from the beach a few days after they are laid.

Before the Ostional Wildlife Refuge was created, the consumption of eggs was not regulated. They were even given to pigs for food. But since the late 1980s, legal limits have been set on their use, and now the amount that may be collected is much smaller.

[Gerardo]: According to our estimates, 1% of the eggs laid by turtles are collected. To put this in perspective, one arrival can lay anywhere from 5 million to 35 million eggs in a week. And the community collects about half a million or less.

[Luis Fernando]: Although some scientists say that, depending on the arrival, much more is collected than Gerardo says. It is an ongoing debate right now. And there is an important fact here: 90% of the eggs that are laid in a mass arrival never become baby turtles. Many are destroyed by turtles that come to nest where another has already laid its eggs. Others are eaten by predators. And so on. That is the justification for their consumption by humans.

Some environmental conservationists oppose the Ostional model. They feel that the sale of eggs should be absolutely prohibited and that any consumption is harmful to the turtles.

But for others, Ostional is seen as a success story because it mixes protection of wildlife and the environment with the economic and social development of a community. For example, the sale of eggs brings Ostional about $300,000 in annual earnings. That is just from sales and without counting the income brought in by tourism, from people who come to see the nesting turtles.

Egg collecting is managed through the Ostional Integral Development Association, which has just over 200 members. Only the founders, who are the people already living in Ostional before the creation of the refuge and their descendants, can be part of it. 70% of the profits are distributed among its members; that means each one receives about 800 dollars a year, and the rest is invested in community improvement—improving the infrastructure of the area and supporting members with resources to go to medical appointments, scholarships for students, and pensions for senior associates.

But in recent years, scientists like Gerardo have begun to notice something worrisome in Ostional.

[Gerardo]: You can see the turtles less than 100 meters from the coast. Many of them in the brown water. Light brown, dark brown. And strangely, they do not come up to nest.

[Luis Fernando]: The turtles come to Ostional, but do not go up to the beach immediately. And this has an explanation: When it rains, that water makes the most important river in the area, the Nosara, which flows into the sea, grow and collect more sediment, that is, soil, sand, rocks, from nearby places.

It is not until the waters become more transparent, in a matter of hours, that the turtles will come up to the beach.

The conclusion of the scientists is clear:

[Gerardo]: If the main objective of the refuge is to protect the turtles, then the turtle habitat depends on the conservation of the Nosara River.

[Luis Fernando]: The worry is that, currently, that task feels daunting.

South of the river, about 10 kilometers from Ostional, is Nosara.

[Ethel Araya]: All these lots adjoin one of the association’s protected forests.

[Luis Fernando]: This is Ethel Araya, a resident of Nosara. For many years, she was part of the Nosara Civic Association, a community development organization. She is showing us around a sector near one of the beaches.

[Ethel]: Back then, it was very normal to see monkeys walking around… eating some of the leaves, especially when they are fresh. And there was a mountain almond tree, which is always green. So there was always food there.

[Luis Fernando]: And she speaks in the past tense because she is describing a sector that sums up the concern felt by Ethel and many other Nosareños.

[Ethel]: And right now it’s under construction; they didn’t leave a single tree.

[Luis Fernando]: An area that used to be green is now full of buildings, made of concrete. Not just houses, but apartment units and luxury hotels.

Ethel first came to Nosara about 13 years ago. She was about to graduate from college with a degree in Economics and was thinking of pursuing graduate studies abroad, when she was offered a job as a babysitter for the owners of a hotel in Nosara, five hours away from her town. She was planning to stay a few months and she was in need of money, so she accepted.

[Ethel]: The hotel is kind of hidden among a lot of local vegetation. So when you’re there, you feel like you’re in a jungle, and you actually are, you know? Monkeys walk by, all the fauna you can imagine walks by.

[Luis Fernando]: She remembers that on the first day she walked along a path between huge trees and came to a beach.

[Ethel]: To that large open area that is Playa Guiones, which is beautiful, you know? It is a fairly long beach with light sand, nice waves, low tide. There are some spectacular pools for swimming as well.

[Luis Fernando]: Ethel grew up in a place very different from Nosara. In what is known as the Central Valley, in an urban area, with a finite horizon of mountains at each cardinal point, between houses and concrete buildings. And what she felt in Nosara was something she had never experienced…

[Ethel]: That sensation of freedom and space that you feel being on the beach, being at the sea.

[Luis Fernando]: There is a saying in Nosara: Those who bathe in the Nosara River stay there forever. Ethel went in.

[Ethel]: And here I stayed.

[Luis Fernando]: In love with its landscape, its people, its philosophy…

[Ethel]: I think it is the vision that human life can exist in harmony with other species, with nature.

[Luis Fernando]: If you fly over Nosara today in a small plane, it’s hard to see the houses among so many trees. It feels secret, hidden, a treasure. There are two main beaches there: Guiones and Pelada. Near Guiones, where the waves are calm for surfing, is the most touristy part, with hotels, bars, restaurants, travel agencies, and yoga studios. Rocky and less traveled, Playa Pelada is a place that still feels remote, practically desolate.

There is also the town of Nosara proper, where many Costa Ricans and foreigners live and where you find everyday things: a bank, a post office, a police station, a few shops, a school. It is a cosmopolitan place, where you can hear different languages in a matter of meters, and where dollars and local currency are handled interchangeably.

But the vegetation that surrounds the community and makes it feel secret is being replaced by more and more construction.

[Ethel]: On the hills of Nosara, in the back side of the San Juan Hills, all those mountains, right?, that you climbed three years ago and there was nothing, now they are all subdivided and many were sold and many are under construction.

[Luis Fernando]: Nosara is having an explosion of real estate development aimed, more than anything, at foreign tourists. In 2022 alone, 131,000 square meters were built in Nosara. This is the largest concentration, in number of square meters built, in the entire province. Some of the buildings are valued at millions of dollars—in a country where the average household income is about $1,600 dollars a month.

Basically, Nosara is experiencing a gigantic advance in a gentrification process that has been going on for decades. Gentrification occurs when people of the upper- or middle-income-class displace lower-income-class people from the area where they have historically lived. Here, the upper class are foreigners, especially from the United States, who saw in Nosara a quiet and remote place to vacation or retire.

But let’s step back for a moment to understand how Nosara got to this point.

A little over 50 years ago, the landscape in Nosara was a savannah—treeless, large flat expanses for cattle ranching. Around that time, an American businessman named Alan Hutchinson arrived in the area, and what he saw was a town with a few Costa Rican families engaged in agriculture, fishing, and working cattle. A poor town, far from everything, and with a lot of real estate potential in the parts close to beautiful, immaculate beaches. So he began buying land near the beaches…

[Ethel]: And he began a project called Playas de Nosara.

[Luis Fernando]: He divided the land into lots and began selling them in the United States. Hutchinson promised golf courses, drivable roads, luxurious resorts. All kinds of things.

[Ethel]: People started buying, but he didn’t or couldn’t keep his sales promise of everything they would find here.

[Luis Fernando]: Basically, the project was overly ambitious, and he really didn’t have the money. In order not to lose their investment, the Americans who had bought land in Nosara decided to unite and formed the Nosara Civic Association.

[Ethel]: And so it is the association that begins to do all the road maintenance work, security, electricity, water. Basically, if you wanted to live in Guiones and Pelada, you had to be part of the Civic Association because they were the one that managed all those services.

[Luis Fernando]: Over time, more and more people came. Some to stay, others to visit. Foreigners and nationals. Suddenly, the families that had resided in Nosara for decades found that the most profitable thing was to work in tourism. Hotels and restaurants were being built constantly.

And it was not only foreigners with white skin and light eyes who came to Nosara looking for a place away from everything. Families arrived from other places in Costa Rica: San José, Limón, other areas of Guanacaste, even from Nicaragua, looking for work in the service sector. And this went on until a community had been formed where shanties and millionaire houses coexist in an area of a few kilometers, and where the cost of living is extremely high.

[Ethel]: You can’t find a nice apartment, and it may be a studio, for less than $1,000 dollars. I mean, it’s crazy.

[Luis Fernando]: $1,000 a month for rent in a country where, let’s remember, the average monthly income for families is around $1,600.

This displacement of people also had consequences on the local ecosystem.

[Gerardo]: The issue is that there was a displacement of the native population towards the banks of the Nosara River, and various areas of nearby rivers were even filled with makeshift settlements.

[Luis Fernando]: This is Gerardo Chaves again:

[Gerardo]: But everything comes together in an interesting issue, and that is that the Nosara River begins to have more erosion problems.

[Luis Fernando]: Erosion occurs when a river carries stones, dust, and sand from one area to another. And this is influenced by human constructions that wear down the soil and create more sediment, which the river carries to the sea.

[Gerardo]: When you view Ostional from the air, you can see the plumes of sediment entering the sea.

[Luis Fernando]: Huge expanses of land that flow from the rivers into the sea—the brown water that Gerardo was talking about a while ago. He believes that, if the erosion continues, that is, if indiscriminate construction continues in the Nosara river basin, the future of the turtles that come to the Ostional beach is in danger.

[Gerardo]: It has been observed that they recognize beaches, they recognize nesting sites, by smell. So, if you change the chemical conditions, for example, of the water in the Nosara River, you are changing the chemical conditions of the beach.

[Luis Fernando]: And how are the chemical conditions of the water changed? By filling it with sediment. More sediment means a beach with a different smell, and because the turtles are guided by that smell, it may be that in the future many of them will not find a place to nest. And the thing is that turtles nest on the same beach where they were born.

[Gerardo]: And what can you expect from that? Well, you could expect a negative effect.

[Luis Fernando]: One fewer beach for turtles to nest in relative safety. And the economic debacle of a community that depends almost entirely on these animals, such as Ostional.

Now, the magnitude of the potential damage cannot be estimated yet. It may be a small effect, or it may be catastrophic. For now, the turtles continue to come, although changes in their behavior are already being noticed.

But the erosion that is coming down to the sea through the Nosara River is only part of the story. There is also concern over what real estate and tourism development is doing to the water in the area.

[Vanessa Bézy]: My name is Vanessa Bézy. I have a PhD in Biology.

[Luis Fernando]: To better understand what is happening with the water in Nosara, we talked to her. She is the founder and director of the Association for the Conservation of Sea Life and Wildlife. She is a specialist in sea turtle conservation and has been studying the water quality of Nosara since 2019. She was born in Belgium but came to live in Costa Rica several years ago.

Some time ago, the residents of Nosara began to notice that people who came to surf were getting sick.

[Vanessa]: Things like ear infections, eye infections, skin infections, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal problems.

[Luis Fernando]: For other people, it was more of a respiratory problem: congestion, cough. And people also began to notice brown foam in the sea. So a person from the community offered money to set up a project to monitor pollution levels in the seawater.

The study is done weekly, and what they are noticing is that, especially during the rainy season, the levels of seawater contamination go up. Vanessa and her team determine this contamination by measuring the presence of fecal coliform bacteria.

[Vanessa]: It enters the ocean, especially from farms or septic tanks, because we are not managing our wastewater properly.

[Luis Fernando]: In fact, it is estimated that in 2019 only 15 percent of all wastewater in Costa Rica was treated adequately. Old or unmaintained septic tanks allow wastewater to seep into the ground, and from there, with the rain, it gets into the rivers and then the sea.

[Vanessa]: In those coastal places, we are all using septic tanks, but it really shouldn’t even be an option. I mean, no way.

[Luis Fernando]: The ideal would be a community water treatment system, that is, a sewer system, but, well, infrastructure for that does not exist in coastal areas. Because of lack of resources, lack of political will. And it is doubtful that it will exist in the next few years.

What is happening in Nosara with water and the construction boom reminds Vanessa of a tragic precedent in the country: the case of the Las Baulas National Marine Park in Guanacaste, the nesting place of the world’s largest sea turtle, the seriously endangered leatherback.

In the 1980s you could see 30 or 40 turtles nesting every night during the spawning season, while only 8 were observed in the entire season from 2021 to 2022. And part of the cause seems to be the tourist development of Tamarindo beach, which divides two nesting sectors of the park.

[Vanessa]: So I see this as a close parallel, and it has happened in other places. We all know of a tourist area that grew very fast and that is not the same as it was before.

[Luis Fernando]: And that is Vanessa’s fear with respect to Nosara and Ostional.

[Vanessa]: Ostional is a community that depends on the turtles. What if all that development has an impact on the turtles and one day they are gone? That’s how the community lives. It’s their economy, it’s their life, it’s their lifestyle, it’s their culture.

[Luis Fernando]: Not only that. The other big question is: what will happen if Nosara, that place that has been sold as a place in tune with nature, does not have a clean beach?

[Ethel]: We must be very clear that if our water is contaminated, people with economic means will be able to migrate and go elsewhere. But the people of the town, the ones who have been here, are always the ones with the least chance of being able to leave.

[Luis Fernando]: This is Ethel again and she is aware of all these problems—water pollution, and how an uncontrolled real estate boom is affecting Ostional. She recalls one day when she was walking near where she lives and noticed that a big four-story house was being built.

[Ethel]: And I said, “Something has to be done.” I mean, when I saw that house, I said, “Something has to be done. It won’t give us time.”

[Daniel]: Time to protect Ostional and Nosara.

We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Just before the break, we were listening to Ethel Araya, a resident of the town of Nosara, on Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, and her concern about how gentrification is affecting the area’s ecosystem—in particular, how it could affect Ostional Beach, one of the world’s most important spawning beaches for ridley turtles.

And it was the sight of a multi-story house, an ultra-luxury house, being built near where she lives that told her she needed to do something.

Luis Fernando Vargas continues the story.

[Luis Fernando]: When Ethel told herself that something had to be done to protect Ostional, she understood very clearly what the biggest obstacle was: the lack of a regulatory pan. In short, a regulatory plan in Costa Rica is a document that defines what a municipality’s planning should look like: the real estate development policy, plans for the distribution of the population, land use, streets, public services, conservation and rehabilitation areas. It is a master plan for the organization of a community.

And well, Nicoya, the municipality that has jurisdiction over Nosara, does not have such a plan.

[Ethel]: Some very expensive studies must be carried out, which are studies of environmental fragility and geological. studies. They are very, very expensive studies, and local governments often do not have a way to pay for them. And the government institutions in charge of reviewing them tend to reject them almost de facto.

[Luis Fernando]: Ethel was then president of the Nosara Civic Association, and had been working for a few years on developing a plan for Nicoya, but the process was moving pretty slowly. These documents can take up to 10 or 15 years to be drafted, because it is a very bureaucratic process and involves very complex studies.

So, feeling anxious about the situation, Ethel came up with an idea: draw up a regulation, something less formal than a regulatory plan, that would apply only to the area of Nosara close to Ostional. About five kilometers long. It sounds small.

[Ethel]: But when you start to map it, you realize that those five kilometers are not so small. Those five kilometers encompass a large part, at least of the residential footprint of Nosara.

[Luis Fernando]: Where the real estate boom is happening. The part that could directly affect Ostional the most.

The idea was not new. In fact, residents of the Las Baulas National Marine Park, that we mentioned before, had already done it, and they had succeeded. So Ethel took the proposal to the Nosara Civic Association, and they agreed to draft a document based on studies of the dangers to Ostional.

[Ethel]: It was a simple regulation, which regulates four things.

[Luis Fernando]: First:

[Ethel]: The height of buildings…

[Luis Fernando]: So that the lights from the buildings do not disorient the turtles from the refuge. The proposal was a maximum height of 9 meters for the nearest areas, and 12 for the most distant.

Second:

[Ethel]: The lighting…

[Luis Fernando]: So that, again, the lights cannot be seen from Ostional Beach.

Third:

[Ethel]: The construction footprint.

[Luis Fernando]: That means limiting the amount of space where people are allowed to build within a plot of land. This is intended to ensure that there is space to install septic tanks and handle wastewater. It also allows some species to move through the area without being isolated in protected areas. And finally…

[Ethel]: The type of wastewater treatment system.

[Luis Fernando]: Basically, buildings need to have an adequate septic tank and sewage system. This, as we have said, reduces the risk of contaminating the sea and affecting the turtles. It also ensures clean water for Nosara.

And that’s all. They submitted the plan to the municipality, and surprisingly, the council approved it; it wasn’t a big problem. However…

[Ethel]: That’s when he big brouhaha began, right after it was approved, because the community saw it as something that had been done in secrecy.

[Luis Fernando]: These processes are usually done after consultation with the communities. But they had decided not to make it public.

[Ethel]: Because we knew there would be detractors of the regulation.

[Luis Fernando]: Basically, people who want to develop giant real estate projects.

[Ethel]: So it’s better to say, “Let’s approve the first version and then we’ll start putting it out there,” so that the initiative is not dead before it’s born.

[Luis Fernando]: But since they saw that a lot of people were very upset, the Association decided to start reporting on the regulation.

[Ethel]: A space was opened where every Monday, starting around four in the afternoon—we began in May 2019 and went on until December—queries were received from anyone in the community who wanted to come and ask, so they could go and do that.

[Luis Fernando]: They also held group sessions for nationals and foreigners in order to explain the regulation.

[Ethel]: And they are told, “No, you are going to have the chance. This is not the final version; a final draft will be made…”

[Luis Fernando]: And then they started to see a change…

[Ethel]: People began to understand it and see it differently.

[Luis Fernando]: But not everyone. One of the people who raised their voice the most in Nosara is Jeffrey Grosshandler, an American hotel businessman. We tried to talk to him, but he wouldn’t grant us an interview. He speaks little to the press, but he did speak on a podcast about local situations in Nosara regarding his concerns over the regulation. The interview was in English.

[Jeffrey Grosshandler]: This process to pass construction regulations has left a lot of the people out of the conversation. And it didn’t accomplish a true community participation from day one.

[Luis Fernando]: He says the process to pass construction regulations left a lot of people out of the conversation and failed to deliver real community engagement from day one. He then criticized that the briefings were held during business hours and that the preferred method of feedback was via email.

Additionally, he stressed that the process was not done according to the law and that the publication of these rules was legally incorrect.

[Grosshandler]: It didn’t give to the public, after it was published, how much time was there to respond, or how to respond…

[Luis Fernando]: That it didn’t tell the public, after it was published, how much time there was to respond, or how to respond.

[Grosshandler]: And because of those two parameters being left out of this process, they had to do it again.

[Luis Fernando]: And that is why they needed to republish it.

[Grosshandler]: And it just doesn’t give a high level of confidence in the people, that are, you know, are in charge of this.

[Luis Fernando]: And that this does not generate confidence in the people who are in charge of the regulation.

Ethel admits they may have been wrong in doing the process with such secrecy.

[Ethel]: Perhaps, looking back, it could have been handled differently. That may be.

[Luis Fernando]: And many residents of Nosara are foreigners, most of them from the United States. And processes like those of the regulation are usually handled differently in that country.

[Ethel]: They told me that in the United States this is handled differently. Public consultations are done first, before testing and approving a first draft. So, that’s why the way it was done bothered the foreigners who lived in Nosara.

[Luis Fernando]: But the effort to inform the community continued. The regulation went into effect in February 2020. And… people adapted to it. Of the 283 building permit applications that were submitted from the time it went into effect until June of the following year, only 13 failed to comply with the regulation and 11 of them readapted their projects to fit the new framework.

[Ethel]: And for me, that was proof that, even though what happened had been tense, it could be achieved, because what the regulation was looking for was, again, that philosophy that has made Nosara famous: that man can coexist with nature, to make that a reality.

[Luis Fernando]: It felt like a triumph at the time. But it was short-lived. In April 2020, Jeffrey Grosshandler filed an injunction against the regulation. The argument is a bit complex, but in a few words, he said that it was approved without supporting documents and without following due process, and that this is against the law.

And so, more than a year later, in June 2021, the Administrative Court overturned the regulation.

[Ethel]: The truth is that we were very surprised that, without good support, according to the legal opinion of our lawyers, it was accepted.

[Luis Fernando]: According to lawyers for the Nosara Civic Association, the evidence Grosshandler presented was not strong enough to cause the regulation to be struck down.

Of course, this made another group of people unhappy. One of them was Katherine Terrell, who came to Nosara 5 years ago with her husband, from the United States, and was in love with the same philosophy of life that Ethel fell in love with. Katherine doesn’t speak Spanish very well, so she gave us the interview in English.

[Katherine Terrell]: Everywhere I look, there’s a construction site, concrete being churned, steel poles going up and, you know, bigger and bigger, like higher and higher buildings…

[Luis Fernando]: She says that everywhere she looks, he sees constructions, concrete being poured, poles going up… everything getting bigger, taller, huge projects that don’t fit in with the landscape…

[Katherine]: I mean, really, it’s like someone just pushed a button and, like replicated like North American scale.

[Luis Fernando]: It’s as if someone pushed a button to replicate the American scale. Katherine never found the rules too far-fetched.

[Katherine]: They were not outrageous draconian laws at all. They seemed very reasonable.

[Luis Fernando]: They were not draconian laws, she says. They seemed quite reasonable. So when she heard that the courts had brought down the regulation…

[Katherine]: There just a lot of fury. You know, it was shock, disbelief, anger, you know, the normal stages of grief.

[Luis Fernando]: She felt anger, shock, disbelief. The normal stages of grief.

[Katherine]: And quickly a group formed saying, “Hey, we need to say something. We need to stand up and say something about this. We can’t just be quiet about this.”

[Luis Fernando]: And soon a group was formed that decided they had to make themselves heard on the matter. They needed to protest. It was formed via social media, and in less than 48 hours they had contacted people from the town and decided they would march towards Grosshandler’s hotel, the Gilded Iguana. With one person absent: Ethel.

[Ethel]: In the end I decided not to go because, on a personal level, the situation became a bit complicated.

[Luis Fernando]: She felt that everything had become very tense and decided not to participate.

The march was on a Saturday. There were about 300 people at mid-morning through the streets of Nosara. When they got to the hotel, it was strangely empty. There were only guards. No one came out to meet them.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Luis Fernando]: They played music, sang, danced…

[Katherine]: And I think the most sort of aggressive…

[Luis Fernando]: And the most aggressive thing was when some started chanting, “Out, Jeffrey.”

[March]: ¡Fuera Jeffrey! ¡Fuera Jeffrey! ¡Fuera Jeffrey! The person who doesn’t jump is Jeffrey! The one who doesn’t jump is Jeffrey!

[Luis Fernando]: Local news covered the march.

[Katherine]: In some of the news, you know, they showed us kind of like it seemed like they were making fun of the group, you know, like, “Oh, look at these hippies. They’re just, you know, burning their sage and dancing around for this cause.”

[Luis Fernando]: But according to Katherine, some media covered the protest as a joke. Like, “Look at these hippies, burning incense and dancing for a cause.” But for Katherine it’s not a joke. Far from it…

[Katherine]: There’s a sense of hopelessness. There’s a sense of, “This is going to be the next Tulum.” I mean, it’s very sad, but I think that’s the general sense.

[Luis Fernando]: There is a feeling of hopelessness, Katherine thinks. That Nosara will be the next Tulum, the Mexican tourist destination that is undergoing a strong process of gentrification. It’s sad.

Grosshandler sued her for defamation. According to the lawsuit, Katherine repeatedly published Facebook posts related to the legal dispute over the regulation, damaging his image and good name. Because the process is still open, Katherine preferred not to go into it. But she told us:

[Katherine]: Not that that has affected my sense of self and how I want to serve in this community. But, you know, I mean, for them to use me as an example, that is an indication of the fight in this town.

[Luis Fernando]: As far as Katherine is concerned, the lawsuit has not affected her desire to serve her community. She thinks, however, that with this legal action they are trying to use her as an example of why people should not put up a fight… and that in itself shows the magnitude of the conflict that exists in that place.

For now, she is waiting for the legal problem about the regulation to be resolved, to settle whether it will be implemented again. The regulatory plan for Nosara is not close to being finalized.

Meanwhile, in Ostional, a regulatory plan was prepared for the community, one that also aims to protect the turtles, but which, due to legal loopholes, has not been implemented.

But beyond the documents, Gerardo Chaves, whom we heard at the beginning, believes that the focus needs to be on implementing what already exists.

[Gerardo]: Actually, the current national laws should be enough for that basin to be preserved.

[Luis Fernando]: The Nosara Basin.

[Gerardo]: What happens is that in this country there is a lot of law on paper but little enforcement of that law.

[Luis Fernando]: It’s not that there aren’t enough laws. The problem is that almost nothing that exists on paper is implemented as it should be.

Meanwhile, Ethel resigned from the Nosara Civic Association but continues the fight to take care of her community and Ostional.

[Ethel]: The way things are going, it is easy to lose hope. But I am also aware that there are lots and lots of beauty. Lots of nice things, too, that still make it worth being here.

[Luis Fernando]: The weekend before the interview, for example, she was enjoying one of the Nosara beaches with her husband and her baby. In the distance she could see Ostional, a landscape full of green.

[Ethel]: I was able to see the beauty of the Ostional refuge, the blessing it is to have this beautiful beach and to be in this spectacular place and for my son to grow up in such a place.

[Luis Fernando]: A place where you can still stumble upon a turtle… Or thousands of them.

[Daniel]: This story was reported by Arturo Silva and produced by Luis Fernando Vargas. Arturo is a Costa Rican sociologist who studies the impact of tourism on coastal communities in his country. Luis Fernando is our senior editor. He lives in San José.

We want to thank the Observatory of Tourism, Migration and Sustainable Development of the National University of Costa Rica, and the Alba Sud organization for their help.

Camila Segura edited this story. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano, with original music by Rémy.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Nancy Martinez-Calhoun, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.