Palma Salamanca in Paris

Share:

Daniel Alarcón spent a year and a half investigating the episode ‘The helicopter, the silence, the gunshot, the escape’. He wrote the following article at the beginning of that process, in December of 2018, while he was covering the extradition hearings in Paris.

The first time I saw Ricardo Palma Salamanca in person was in the halls of Palais de Justice in Paris in October 2018. The Palais is just that—a palace—decidedly and unabashedly regal, with long, wide hallways and stone steps that sag like old mattresses. At that October’s hearing, among the gathered exiles, there had been talk of nightmares and torture and stark, frightening memories of life under Pinochet. Seeing Palma Salamanca had brought it all back for them, and they stood together, sharing memories and support, reliving traumas they thought they had buried long ago. The Chilean press had come then, a few French outlets too, and Palma stood among the crowd, stone-faced, with three bodyguards who raised a blanket in front of his face every time someone tried to take his picture. One journalist, a lanky young man in a bad suit who worked for Chilean television, was threatened when he refused to stop taking pictures. After the hearing, there’d even been a brief scuffle, as he tried to snap a photo and a Chilean exile pushed the young journalist to the floor.

When I returned in December, the atmosphere had changed completely. In the intervening months, the French office of refugee resettlement, OFPRA, had granted Palma Salamanca asylum. This did not mean his case was over—technically, extradition and asylum are two separate and independent processes—but in practice it was hard to imagine now that the Chilean state would succeed in its bid to have Palma Salamanca sent back. The chances of a French court contradicting and overriding the decision of the French Office of Refugees on asylum were slim to none. Back in Chile, the case has been all but written off by Palma’s political enemies. I’d been in Santiago when the OFPRA published its ruling and watched as members of the committee formed in solidarity with Palma Salamanca raised a glass of champagne in celebration, a motley crew of middle-aged former militants and victims of the dictatorship toasting in front of the assembled members of the Chilean and international press. A rare moment of satisfaction: the campaigners on Palma’s behalf felt, correctly, as if they’d won.

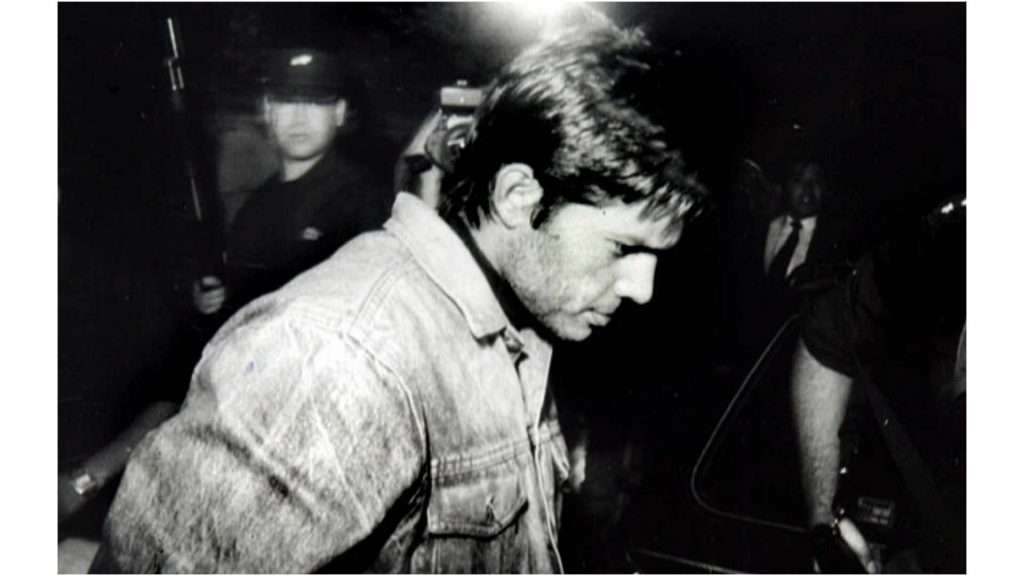

Palma Salamanca was arrested in 1992

Now, in December, there was less press, no French outlets. In the hallway in front of the courtroom, the exiles chatted and vaped, laughed and waited good-naturedly. They’d come to show solidarity, with a confidence that today’s hearing was just a formality.

But still, optimism and confidence are not the same as certainty. The French courts finally denying the Chilean request for extradition—that would be certainty. That would mean this was all over, would mean clarity on the future, stability, and unassailable legality, something Palma Salamanca hadn’t had in decades, even if he’d managed to create a simulacrum of all those things, briefly, in Mexico.

This time, it had the feeling of a reunion, Palma silent at the center of a social gathering, the heart of the party, if not exactly the life of it. Supporters came up to pay their respects, and he accepted each handshake with a smile, a brief, charismatic flash of warmth, and then he would step back and away almost imperceptibly, and conversations would carry on without him. It was as if people were touching him for good luck, or to verify that he was real, this figure who for many exiles is more myth than man. He wore a leather jacket and a scarf, which he didn’t remove, never quite settling in. I asked him at a certain point if this was the way he preferred it, the conversations buzzing around him, but without him. He said it was. If others felt confident, he was wary still.

Not that he was unfriendly, or standoffish. Simply cautious; not a character flaw so much as an adaptation to the extraordinary circumstances which have marked his life since he joined the Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez as a teenager. In October, when the stakes seemed higher, and the uncertainty barely tolerable, he’d been protected, surrounded by an impenetrable mass of Chilean exiles. This time he was more accessible, smiling more, even uncrossing his arms now and then. We waited a very long time for the hearing to begin—another difference from October, when the authorities had seen the size of the crowd and rearranged the docket to allow Palma Salamanca’s case to be heard first. He was given none of that deference this time, and at some point, in the third hour or so of waiting, I turned and saw Palma standing alone in the hallway, an image so startling in context that I did a double take.

The long wait also allowed me to see my surroundings more clearly, or rather to understand something I missed last time: that the courtroom didn’t belong to Palma Salamanca or his particular drama, that Palais was a French institution filled with French stories, and not, as it appeared to be, a baroque outpost of Chile, frozen in amber sometime in the waning years of the dictatorship. A courtroom—any courtroom—is a broadly utilitarian place, where fates are decided, where lives are changed. Not just Palma Salamanca’s life. Somehow, in October, it hadn’t seemed that way, but today, as we waited, a woman came up to me and asked in French which case I was waiting for. She was an Arabic translator, she told me, and had been assigned to an extradition hearing for a man surnamed Djif. Was this it? Was this the courtroom? I answered without thinking: No, I said. There’s no Djif here, and then realized, just as she did, that there was, of course, a Djif here. It was him, that narrow faced gentlemen I’d somehow not noticed because he wasn’t speaking Spanish, the one wearing a heavy coat and a few day’s worth of brown stubble, the one with nervous hands, surrounded by his wife and four children, the youngest still in a stroller. The translator walked away, and I noticied Djif’s wife, in a loose head covering: she was a mess, anxious and clearly afraid. She kept losing sight of her two youngest boys, five or six years old, who entertained themselves by squabbling and stopped only when a police man took their father away. The youngest, sensing the danger intuitively, began to wail inconsolably and fell into his mother’s arms in a heap.

He escaped from jail in 1996

By the time the proceeding began, around 5pm, we’d been waiting for hours, and our energy was drained. A lot of standing. A lot of cameras taking the same picture again and again. People clustering together, then drifting to the benches along the hallway, then back again. Off for a cup of coffee, and then back. When the doors finally opened, Palma Salamanca and his entourage moved in first, then the Chileans, roughly in order of proximity to the man, and once they had filed in, it was the press’s turn. Most of us stood. There were about forty-five people in the courtroom altogether, a smallish, square room that felt stuffy and warm. If I hadn’t been standing, I’d have fallen asleep.

The lawyer for Chile spoke first, referring occasionally to his notes and coming back again and again to crimes Palma Salamanca had been convicted of so many years ago. Not the context that surrounded them, but the bare details of Senator Jaime Guzmán’s murder, for example. What is alleged: Guzmán, architect of Pinochet’s 1980 constitution, ideologue of the regime, taught law at the Catholic University. One day, as Guzmán was leaving class, he came across two men on the stairs, who were apparently waiting for him. They were Palma Salamanca and another FPMR militant, Raúl Escobar Poblete, now imprisoned in Mexico. When Guzmán saw them, he knew he was in danger, so he turned back up the stairs, took a back way to his car. Escobar Poblete and Palma Salamanca went around to the parking lot. Guzmán’s driver couldn’t get away, and the two young men allegedly shot Guzmán as he sat in the back seat. Like any murder, it’s a simple and brutal crime. But in the course of these visits to Paris, I’d often asked Chilean exiles, many of them, what justified the killing, and been met again and again with disbelief, as if they couldn’t be bothered to explain something so obvious. Beyond the moral issue, I’d say, wasn’t it a tactical mistake to assassinate a democratically elected senator at such a precarious political moment? Later, I’d listen back to the tape of these interviews, feel disappointment: if you’re left debating the tactics of murder and not the naked immorality of it, then perhaps you’ve lost the conversation altogether.

Though it was December, a cold wintry Paris afternoon, in the courtroom the heat was soporific, and Palma gently closed his eyes, as if dozing. His French is okay, not great. “I get by,” he’d told me earlier in the week, so I wondered what he thought of all this, if he could understand it all, or if the words piled atop each other, almost undifferentiated, a droning recap of events he’d rather forget. It wasn’t hard to imagine him tuning it all out. Then at one point, the lawyer for Chile described Palma as, “un homme très violente” and I watched as Palma’s eyes shot open, his face bearing an expression of startled, unwelcome surprise.

When the lawyer for Chile’s monologue petered to its conclusion, the state prosecutor spoke. She represents the state of France. Her presentation was most notable for the mention of the previous day’s events in Strasbourg, where an Islamist gunman shot eleven people, killing two, in a Christmas market. It is more difficult than ever to distinguish between political violence and terrorism, she argued, particularly at moments like these. However, the mitigating factors in the case of Guzmán were the torture he endured in custody, and she seemed inclined to dismiss his confession on those grounds. This was not a fact-finding hearing, there would be no evidence presented to prove or disprove this or that allegation. For the prosecutor, if the confession was procured under torture, it was of no legal value.

Finally, Palma’s lawyer, Jean-Pierre Mignard, spoke. He’s a jovial and witty man, pale, round and jowly, with an element of showmanship that was particularly welcome in the warm and stuffy courtroom. He emphasized France’s long history of standing with those who fought against authoritarian regimes. He noted again and again that Guzmán’s 1980 constitution is, save for some cosmetic changes, still the governing document defining Chile’s politics. I couldn’t help but think of an interview I’d done weeks before in Santiago, when a man close to the Guzmán family looked out the window of his high-rise office building, at the skyscrapers and broad avenues of the clean, prosperous city, and told me with a sweep of his arms that Guzmán was responsible for all of this. That his document—his constitution—had made this unfettered capitalism, and all that entails, possible. He said with a hint of awe. I don’t think Guzmán’s political enemies would disagree, though they might say it with different tone of voice, with gritted teeth. Full of anger.

The long day finally ended past six thirty in the evening, and there was no time for deliberation. The judge announced a recess until January 23rd, struck her gavel and that was that. There would be no end to this strand of Ricardo Palma Salamanca’s story that day. No closure. The waiting continued.

You can listen to the end of this story on the episode ‘The helicopter, the silence, the gunshot, the escape’.