From the Store to the Dump [Extra Episode] | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at Lupa.app.

Translated by Lingua Viva

[Daniel Alarcón]: Hello, ambulantes. I’m Daniel Alarcón. As the year comes to an end and while we’re having a well-earned rest, we’re going to bring you three episodes from our other podcast, El Hilo, which comes out every Friday. For those who haven’t heard it yet, El hilo is news-based and covers a different subject every week, those that are being talked about all over Latin America.

We’re very proud of this podcast, and we think you’ll like it.

Last week we shared an episode from Puerto Rico with you, and today we’re bringing you one from Chile.

We hope you enjoy it.

Thanks.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

[Host]: The longed-for garment, the perfect size, and the dream label aren’t in a huge store or a spacious closet, but rather in the Atacama Desert in Chile.

[Journalist]: Literally a graveyard for second-hand clothes.

[Eliezer Budasoff]: We’ve all seen photos of the piles of clothes in the Atacama Desert, right? How did you react when you saw those images?

[Beatriz O’Brien]: I think my reaction was, ‘Well, at last these photos are spreading outside the circle of those of us who knew that this has been a problem for many, many years.’ It’s great that they’re appearing in the international press.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

[French journalist]

[Host]: A mountain of discarded clothing […] cuts a strange sight in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

[German journalist]

[Beatriz]: It’s great that we’ve got the world’s attention as a result of this problem, isn’t it? Which is, you could say, like the tip of the iceberg of a big problem that lies behind. Now the discussion has been opened and we can start talking about this subject.

[Silvia Viñas]: This is Beatriz O’Brien. She is a sociologist by trade and has spent years working on issues related to fashion, the textile industry, new economies, and sustainability. She is also the national coordinator in Chile of Fashion Revolution in Chile, a global movement that aims to reform the fashion industry.

[Eliezer]: We spoke with Beatriz to understand what’s behind the photos of the piles of clothes that tower over one of the driest deserts in the world.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVO)

[Journalist]: Around 59,000 tons enter through port Iquique’s free zone every year.

[Host]: There are thousands of tons of clothing items, including many that are unworn.

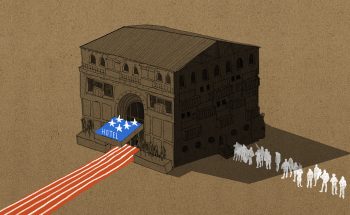

[Beatriz]: The mountain of clothes that we can see there, we know they’re not clothes that have been used in the country, but clothes that come from somewhere else, so this gives us the cue, or the obligatory cue, to start talking about the global textile industry. We’re like the dumping ground for a worldwide fast fashion system.

[Silvia]: Welcome to El Hilo, a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios and VICE News. I’m Silvia Viñas.

[Eliezer]: And I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

[Silvia]: Today: What does the clothes dump in the Atacama Desert tell us about the global textile industry, and about ourselves as consumers?

It’s January 21, 2022.

[Beatriz]: It’s a very shocking sight, because the desert is there too, where there is nothing. And suddenly there’s this heap of clothes in a place where you think, ‘Oh, nobody lives there,’ or ‘There’s nothing there.’ But you say, ‘How did those clothes get there?’ It’s as if a flying saucer had come down and left them there.

[Silvia]: That’s a bit how it feels to look at the photos from the outside.

[Beatriz]: But that isn’t quite the case, because the city of Iquique is really near, right? Iquique is on the plain, and when you leave town, you start climbing up to the altiplano. So it’s a matter of loading up a truck or a van and going off to dump clothes, isn’t it? It isn’t that hard, right?

[Eliezer]: The question is why there is a need to throw clothes away there, and in those quantities.

[Beatriz]: I’d say that, in South America, Iquique is the main port of entry for second-hand clothing.

[Silvia]: The press has reported that, every week, millions of items of used clothing arrive at the free zone of Iquique, known as La Zofri.

[Beatriz]: La Zofri is Iquique’s major market, where clothes are sold wholesale, and retail too, but people buy wholesale. The clothes come in bundles or in bales.

[Eliezer]: Bales are compacted packages of clothes that contain a mixed variety of garments.

[Beatriz]: Recently, larger bales weighing around 50 kg have been arriving. But most of it is second-hand clothing, because in Latin America, we always have data issues, don’t we? We don’t have much data on the subject, but we do know that the clothes come primarily from the United States.

[Eliezer]: But also from Canada, Europe, and Asia. Over the years, it’s become customary for unsold garments—of which there are many—to be dumped in the desert.

[Silvia]: Beatriz, what type of clothes end up in these dumping sites in the desert?

[Beatriz]: They’re clothes that are from charitable organizations, clothes that people no longer need. In the north, people tend to donate clothes to these charities.

[Silvia]: When she says “north,” Beatriz is mainly referring to the U.S. and Europe.

[Beatriz]: The idea still persists that because there are people who need clothes, then “What good people we are, donating these clothes we don’t need to poor people in the south who need them,” when we know that in reality the situation isn’t quite like that, because nowadays it’s not the same as it was 30 or 40 years ago. Today, clothes have become much more accessible, don’t you think?

[Eliezer]: And that’s changed the way we consume clothes. Now we keep them for much less time than before.

[Beatriz]: For our grandparents, clothes were probably belongings that people took good care of, right? Clothes were passed down from one sibling to another. Buying clothes wasn’t cheap. Forty years ago, buying clothes wasn’t cheap, was it? You would be only bought one of something. I grew up in the generation of the 80s, when you would have one pair of sneakers bought for you every year.

[Eliezer]: Yes, absolutely, yes.

[Beatriz]: You had to look after your sneakers, and if they got damaged, your parents would say, “But how?” And they would glue them back together or send them to the shoe store, and they repaired your shoe and you’d get it back and go on wearing it. So, clothes have experienced a striking devaluation.

[Silvia]: Now, it’s estimated that we throw 80% of our clothes and other textiles straight into the trash.

[Eliezer]: And it’s not only that clothes have become cheaper and more accessible. There’s the issue of volume. It’s no longer about the Autumn/Winter and Spring/Summer seasons. There are brands that launch up to fifty-two micro-seasons per year. In other words, one per week.

[Silvia]: There’s a reason it’s called fast fashion.

[Beatriz]: The fast fashion industry sells fashion, albeit an extremely fleeting form of fashion.

[Silvia]: You only need to search for the word “haul” on YouTube to come across thousands of videos of people unwrapping their clothes orders.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

[Unboxing]: OK, the first thing I can see here are some jeans that look really cool. Mom jeans—essential in your closet.

[Unboxing]: This is a tie-dye style jacket, but in neon and white.

[Unboxing]: Why did I buy myself this pleated skirt? Because first of all the schoolgirl look is really big…

[Beatriz]: Fast fashion isn’t designed to last. So they’re things that, for example, one year heart prints were in fashion, just to mention something silly, and no one was interested in heart print clothing until twenty years later. Therefore, when these bales arrive with clothes from two, three, four, five or six years ago, with heart prints, here in Chile people are on social media too and they’re consuming fashion as well, and they don’t want heart print skirts anymore because they know that they were in fashion in 2017. So nobody wants that fast fashion, you get me? It’s not like shipments are arriving of classic-cut black linen dresses that any woman would want. No, the clothes that arrive are very seasonal.

[Silvia]: And for that reason, in the landfills in the Atacama Desert you can even find clothes that still have the tags on. Clothes that were never sold. The fact is, in the fast fashion industry everything moves really quickly.

[Beatriz]: Ultimately, the large fast-fashion chains compete for speed, don’t they? Who can reach the stores first, or who can bring the catwalk style to the customer and make it accessible in the shortest time possible.

The big battle between these brands is in logistics and distribution, and the search for new markets. Latin America is a major new market.

[Eliezer]: Particularly if we consider that the European and U.S. markets are already saturated with fast fashion. In Latin America, Chile is the biggest consumer of clothes. And almost all of them come from abroad.

[Silvia]: And it’s not just that. Chile is also the country that imports the most second-hand clothes in the region. Media outlets have found that there are over 50,000 tons of used clothes every year… and 70% is estimated to end up in illegal landfills or incinerated.

[Beatriz]: The importation of secondhand clothes in Chile has practically no legislation. I mean, they have to enter through customs, right? Through customs. You pay duties that are relatively low and you can bring in as much clothing as you like.

[Eliezer]: This makes it fairly unique in the region.

[Beatriz]: Peru has regulations. Colombia has regulations. Argentina has regulations too. It’s prohibited in Paraguay and Bolivia, Bolivia does have a law banning the importation of second-hand clothing, meaning that the clothes that enter Bolivia are contraband.

[Silvia]: Smugglers take advantage of the fact that Chilean legislation is much more permissive than in countries like Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay. And this contraband also feeds the problem of the dumping sites in the Atacama Desert.

[Beatriz]: When the bundles or bales are purchased, the people who smuggle the clothes into the rest of South America sort through them, and right there they throw away the clothes that they’re not going to take and that aren’t going to be transported to the other countries.

[Eliezer]: Beatriz, what are the consequences of that dump being there?

[Beatriz]: Well, first, when the clothes are left there, the first thing they start to leach are chemicals. Because although it doesn’t rain in the desert, there is wind and, with the sun and the altitude, the clothes are going to start to decompose. There’s no rain, but there is camanchaca, which is a type of mist that comes in from the coast and the clothes get damp either way.

[Silvia]: Beatriz explained to us that the first chemical released by the clothes is the one used to sanitize them to be shipped to Chile, or upon arrival in the country.

[Eliezer]: Those chemicals contaminate aquifers, which are natural underground water reserves that are hugely important for the world’s supply of drinking water. However, Beatriz told us that there many other chemicals that are released from clothes when they decompose in a landfill site:

[Beatriz]: Because clothes involve a lot of chemical processes, right? There’s a finishing process so that they feel soft. In fact, there are estimated to be 1,900 different chemicals that the textile industry requires for garment finishing. What about jeans? Jeans have many different finishes: starting with stone washes, with anilines, with stone washes, with the finish to make them soft, with the fixing agent so that the chemicals remain attached and so that they don’t give off fluff. It depends on what the composition of the garment is, on which chemicals and which characteristics the garment needs, on which chemicals are going to be used and what processes the factory needs to follow, and over time all those chemicals will gradually be released and contaminate subterranean aquifers.

[Eliezer]: Another big problem that Beatriz mentioned, and which can be seen in the Atacama Desert, is incineration.

[Beatriz]: The photos that were published in the international press are of thrown-away clothing, right? Kind of like a landfill, piled up there. But those clothes are burned, and we know that they’re being burned. We know that there have been burns that have lasted for weeks as well, because they set fire to the clothes. It’s a bad practice. Among that clothing, down there, there are shoes as well, there are lots of shoes. Sometimes there are, I don’t know, life preservers, for example. There are also fishing nets mixed in with everything. I mean, there are clothes, but there are other products too. And what they do to stop these clothes from being noticed is burn them.

[Silvia]: And although from the images it would seem that these landfills are in the middle of nowhere in the desert, they are actually quite close to places where people live.

[Beatriz]: These are very poor communities. In the north of Chile there are communities that are quite humble. The living conditions there are very precarious because it’s the desert too. So, in the desert you don’t need, let’s say, strong housing structures or anything like that. They are communities that are also made up of migrants who settle in this empty landscape. There aren’t a lot, but there are people. And there are children as well, and there are loads of photos of people who go and rummage around there, looking to see whether there is anything among all this that is worthwhile and can be resold.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

[Journalist]: There are many people who come on a daily basis to look through the piles in search of the best garments in order to resell them in their neighborhoods.

[Journalist]: Others, in contrast, take them away for themselves or for their children to wear.

[Woman]: I don’t do it to sell, but for me.

[Journalist]: For you.

[Venezuelan migrant]: We came to look for clothes because we honestly don’t have any, because we actually threw them all away when we were making our way here with backpacks.

[Beatriz]: So there are a variety of environmental impacts, and they clearly have to do with the neighboring communities. One is the contamination of subsoil, and another is air pollution due to incineration. The garments also release contaminating fibers. A third example is the number of infections that these clothes can bring with them, right? Because even though it’s in the desert, scavenging birds can still show up, as can rats… it’s still a landfill. Even if they’re clothes, it’s a dump.

[Eliezer]: After the break: how our use-and-throw-away culture contributes to the problem, and some possible solutions. We’ll be right back.

[MIDROLL]

[Silvia]: You’re back with us on El Hilo. Before the break, Beatriz described how the clothes in the dumping sites in the Atacama Desert release chemicals that contaminate the subsoil, and how the incineration of these clothes also affects the environment and the health of the people who live nearby. But the clothes that we wear start contaminating long before they reach a landfill.

[Beatriz]: The big problem we have nowadays in the textile industry, it has to be said, is without a doubt overproduction and overconsumption. Because everything we have comes from nature, even though we might say that there are things that are made of plastic, clearly created by human beings, it still comes from fossil fuels. Everything we have comes from nature, and the fashion industry is demanding a great deal. It’s demanding in terms of land, right? To plant cotton, I need land. So what happens with that land? Where do I get that land from? Because there’s only so much land available in the world.

[Eliezer]: Beatriz mentions cotton because it’s one of the most in-demand natural fibers. The countries that produce the most cotton are India, China, and the United States. Other leading producers include Brazil, Pakistan, and Turkey.

[Silvia]: There’s a whole history behind cotton and how its production has changed over time to adapt to this global textile industry that Beatriz describes as giant and voracious. But what you should know now is that with the increased demand for cotton, the natural plant has started to be replaced by high-yield seeds. That is, the cotton that is used nowadays to make our clothes has been genetically modified.

[Beatriz]: The cotton we use today is more productive, but it requires an astonishing amount of water.

[Eliezer]: This cotton production has had severe consequences. It’s a matter of looking at what happened to the Aral Sea. This lake, which borders Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was one of the biggest in the world less than a century ago. Now it’s virtually dry.

[Beatriz]: And now there’s a desert. And you look at those images and they’re striking. There are boats in the middle of a desert, of what used to be a sea.

[Eliezer]: And now only 10% of its water volume remains.

[Silvia]: Cotton and polyester are the fibers most used in making the clothes we wear, and processing them involves huge amounts of resources.

[Eliezer]: And the chemicals that Beatriz was talking about, that are released from the clothes in the landfills, start contaminating a long time before they end up there.

[Silvia]: She gave us an example in China, where more than half of the world’s textile production takes place.

[Beatriz]: They have rivers that, I don’t know whether you’ve seen it, but there are rivers… for example, there’s a river that’s completely blue because they use indigo dye to make jeans. And that pollution obviously has to do with people nearby being poisoned, right? In that it is breathed in, in that the water can no longer be purified.

[Silvia]: And of course, the textile industry pollutes too, like any industry, due to the huge amount of energy it uses.

[Eliezer]: Nowadays, you can see various clothing brands promoting more sustainable lines, even from these brands that produce fast fashion. Do any of these things actually make any difference?

[Beatriz]: Unless we slow down consumption and decrease production, they won’t make a difference. That’s the truth. In other words, what we’re seeing here in Chile is like a small part of the problem. If we look at Asia, a massive part of the problem is there. In India, there are entire generations of children who are born with problems due to the pesticides we’re applying to cotton. I mean, if I were to tell you about all the problems that the industry causes, even modern slavery, and loads of things happening that are related to this excessive demand that we place on the textile industry. The problem is the amount of clothes we have. There’s too much clothing in circulation.

[Eliezer]: And there’s a practice that has become commonplace among mass brands: they destroy the clothes that they don’t sell. Some years back, for example, a media outlet reported that H&M had burned sixty tons of new and unsold clothes over a period of four years. In addition, trash bags full of new clothes, with the tags still on but cut in half to ensure that nobody could wear them, were found in one of their stores.

[Silvia]: To counteract reports like that, large clothing brands, including H&M, have launched lines that are supposedly sustainable. But Beatriz says that this isn’t going to solve the problems created by the industry, despite many of us falling for that marketing trick.

[Eliezer]: There’s a concept that doesn’t only apply to the textile industry, but which we see a lot when buying clothes: greenwashing. That is, when a corporation promotes itself as having ecological awareness, or presents a product as “sustainable” without actually making any significant changes.

[Beatriz]: They have more and more conscientious lines like organic cotton, fair labor. In fact, they add a sustainability label, they have a line that’s sustainable, but all the rest of the clothes are still made in the same way. “Oh, yes, isn’t that nice? I bought a linen blouse and it says it’s sustainable.” But sustainability is a subject that has lost its meaning somewhat in recent years, because nobody knows exactly what it means to talk about sustainability. We all have faith and hope that the environmental impact is lower compared to another garment that isn’t sustainable but, in reality, sustainability is so many things at the same time that I think no company manages it. Not even the smaller brands that have more control over their production chain manage to control every aspect. Right? I’d say that you have to think, right, if you’re talking to me about sustainability, what are you talking to me about? That it uses less water, that you’re paying people better, or what? What are you getting at with that? Because they say: “Ah, sustainable, right now I’m buying sustainable.”

[Silvia]: We wanted to ask you exactly that. What can we do as consumers to stop fueling this problem?

[Beatriz]: We have a responsibility as consumers. I think it’s quite important, to inform ourselves, right? There are a lot of people who feel overwhelmed by the amount of information they have to process in order to be a conscientious consumer. But there isn’t that much either. Over time, you learn and you assimilate it, and it turns into a habit or a practice. And once you have that practice, it’s already incorporated. And when making choices, we human beings are pretty quick at reading codes, aren’t we? So, you already know… “Hmm, look at this.” Starting with the company, if it’s a company that handles huge volumes, then it’s impossible for it to be sustainable.

[Eliezer]: In addition to educating ourselves, which can feel overwhelming at times, Beatriz gave us some practical tips:

[Beatriz]: There’s a new term in textile industry sustainability which, in the fashion industry, is called the sharing economy. And the sharing economy is creating a lot of platforms that are also being enabled by the digitization and the globalization of communication, examples of which include platforms for selling and swapping clothes.

[Silvia]: Beatriz says that we have to make an effort to not use new resources. Instead of buying a new dress, for instance, we can visit a dressmaker so they can help to alter or repair an old one. Or we can speak to upcyclers or recyclers who can help us to transform things into something totally new. There are a growing number of options.

[Beatriz]: Exchange and second-hand fairs, swapping among friends, putting it for sale on the internet, giving it away, or asking for it from somebody who’s giving things away, right? It has to be done collectively. I believe we have to start thinking about giving up material possessions a bit, and getting products to circulate among us.

[Eliezer]: Basically, it’s about transforming that use-and-throw-away culture, where people can’t stand the idea of repeating a look.

[Silvia]: Meanwhile, the amount of textile waste that has accumulated in the Atacama Desert is so big that the local authorities say they need a sum of millions to remove it: more than US $3.5 million.

[Eliezer]: It’s a massive problem, but there are people who are looking to mitigate it. For instance, there’s a factory in the area that takes the waste and turns it into insulation panels for social housing.

[Silvia]: And part of the solution involves regulatory proposals. As we mentioned before, the law in Chile is fairly lax, but there are initiatives that may not resolve the problem in the desert but do seek to build awareness. One such initiative is the draft eco-labelling bill.

[Beatriz]: Eco-labelling proposes that, if you buy something, let’s say a pair of jeans, that the label says: these jeans used fifty liters of water, this amount of chemicals, this many people to make them, how long they took to make, where the fabric was produced, where they were manufactured, how they reached you… right? Whether they were transported on a plane or on a boat. How many places did they pass through? The eco-labelling law should have every single piece of that traceability information.

[Silvia]: However, there is no clarity regarding when that draft bill might proceed. It has been at the first stage of debate in the Chamber of Deputies since August 2021.

[Beatriz]: Another bill is the REP Bill, the Extended Producer Responsibility Bill.

[Eliezer]: This is a law that makes producers and importers from different industries responsible for the trash and waste that their products generate. It aims for them to take responsibility by setting collection and recycling targets, among other measures.

[Silvia]: This law was passed years ago in Chile, but its implementation has been gradual. Initially, the clothes and textile industry wasn’t included in the law, but a few months ago, the Ministry of the Environment announced that this would change. And if it materializes, it should work as follows:

[Beatriz]: The Extended Producer Responsibility Law should say that, wherever you buy an item of clothing from, the producer has to give you an end-of-life solution for it. In others words, if I buy a pair of jeans in Walmart, to give you an example, Walmart has to have a repair system in the event of my jeans being damaged; I don’t know, maybe I have to take them to the workshop and they have to mend them for me, or if I no longer know what else to do with them and I go and give them to Walmart, they must have a recycling center or a partnership with a recycling center and transform them into something else. They have to take responsibility for what they launch on the market.

[Eliezer]: For Beatriz, countries urgently need to think about their position in the global textile industry.

[Beatriz]: Fast fashion has only been around for 30 years, hasn’t it? Clothes have existed for as long as people have. So I think that we’re at a point where we can think about what we want our textile industry to be like, as well. In Latin America that’s a big concern for me—we have no say in any decisions. What type of textile industry do we want?

[Silvia]: Beatriz says that the disadvantage Latin America has in the textile industry is clear in economic terms. That is, we haven’t been able to compete with the big industries like China. And that leaves us with few options.

[Beatriz]: We have no economic sovereignty with regard to the way we manage our capital, the number of jobs we can offer, the work we can carry out around the textile industry. We can’t decide anything because we already have a position in this international order; this is the place assigned to us. We’re in a situation of dependence regarding our textile industry and the rest of the world; “Go on, send us everything that you don’t want and we’ll see how we deal with the trash here.” As much as we say that we’re a country, we’re a developing country. We’re receiving the rest of the world’s trash

[Eliezer]: And the textile industry, according to Beatriz, isn’t something that we should view from an economic perspective alone. Clothes are culture too.

[Beatriz]: Wearing clothes isn’t just covering or wrapping yourself up. It has to do with so many things, with our history, with women, with the fact that we’re born and they wrap us up in a blanket and then we die and they wrap us up in a blanket, right? I don’t know, clothes have a lot of history and our industry has trivialized that, as have we ourselves. The waste that exists in the north is also the waste of our culture, isn’t it?

[Daniel]: This episode was produced by Silvia Viñas and Daniela Cruzat. It was edited by Eliezer Budasoff and me. Desirée Yépez did the fact checking. The sound design and mixing were done by Elías González, with music composed by him, Rémy Lozano, and Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the El Hilo team includes Mariana Zúñiga, Inés Rénique, Denise Márquez, Samantha Proaño, Paola Alean, Laura Rojas Aponte, Juan David Naranjo Navarro, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Camilo Jiménez Santofimio. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO of Radio Ambulante Estudios. Our theme song was composed by Pauchi Sasaki.

El Hilo is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios and Vice News. Thanks to those of you who have joined Deambulantes, our membership program. We depend on members like you in order to safeguard the type of journalism that we do at El Hilo. If this podcast has helped you better understand what is happening in Latin America, consider making a donation today. Regardless of the amount, your contribution will help us ensure that our thorough and independent journalism can continue. Sign up today too at elhilo.audio/apoyanos. Thanks a lot!

And to keep up with the most important news in the region and the development of this and other stories that we cover, follow us on our social networks. You can find us on Twitter and Instagram as el-hilo-podcast.

I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.