Superman in Chile | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

►Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at Lupa.app.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

This story begins in a school, with a six-year-old boy who is told by his teacher that his father is waiting for him outside. We are in Santiago de Chile, November 1987. The country has been under a dictatorship for 14 years and that boy, Matías Celedón, already knows about danger—there are times when he has picked up the phone at night only to hear threats.

[Matías Celedón]: I remember being asleep, and my mom would pull my sister and me out of bed when my dad was on a television program maybe, and she would say, “We just got a threatening phone call saying there’s a bomb…”

[Daniel]: His father, Jaime Celedón, is a renowned theater actor, although in those years he was more involved in radio and advertising. He is a founding member of the Teatro Ictus, one of the few theater companies that are still standing after many years of intimidation. Together with Matías’s mother, they have made an effort to keep him and his siblings away from that atmosphere of terror. But the terror seeps everywhere: Matías has heard snippets of conversations, he has turned on the television and has heard the words “attack,” protests,” “dead.”

[Matías]: As a child one perceives, probably not with the scope of reality of what was really happening, but still, with a feeling that we are in a situation of fear.

At six years of age, nothing terrifies him more than the dictator Pinochet.

[Matías]: Since childhood I knew that he was a bad person, that he was a murderer. I mean, he was the great antagonist. I mean, if there was a bad guy that Superman had to defeat, that guy was Pinochet.

[Daniel]: Superman. The issue is that Matías was a fan of Superman. A serious fan. He drew him everywhere, he made costumes, he used gel to make the curl on his forehead. He liked him so much that once he pretended to be sick to avoid going to a classmate’s birthday party, because he wanted to keep the Superman toy his parents had bought for him. Perhaps it is even an understatement to say that he was a fan… Superman was something more.

[Matías]: After my father, perhaps, and my mother, he was the most important person, if he was a person and not a superhero. At that time I didn’t make the distinction, but… but he was basically God.

[Daniel]: He watched the movies starring Christopher Reeve over and over again. His older brother played them for him, and he was fascinated by that man who had bullets ricochet right off him, who could even turn back time, flying full speed counter to the rotation of the Earth. Who was not afraid of anything. In the 1980 movie “Superman 2,” he saw how a boy fell into Niagara Falls, and he dreamed of being the one who fell.

[Matías]: I said, “This boy is so lucky, how lucky that he fell into the falls” (laughs) “and to be picked up by the superhero.” I mean, like … I didn’t see the risk, but rather the possibility of being rescued.

[Daniel]: Matías thought that Superman was real, like him, only he lived far from Chile. In a city they mentioned in the movies, and sometimes at home: New York.

[Matías]: That dividing line between what you see on the screen and what is happening was never very clear, that is, fiction and reality; when your father is an actor, it tends to be blurred. You never really know if he’s serious or joking.

[Daniel]: And his dad, Jaime, teased him all the time. It was his way of playing with him. Sometimes, with a worried face, he would approach him saying he had something very serious to tell him… he would put on a dramatic tone, wait a bit, and say that he loved him very much. And he laughed. Actor dad jokes.

[Matías]: Kind of preparing you for some bad news, a kind… kind of dark thing, but he had that way of being theatrical.

[Daniel]: But let’s go back to the morning when his teacher told him that his dad was waiting for him outside. It was still very early; he was in the middle of a class, but his dad had to talk to him about something that couldn’t wait.

When they met, he asked him to come with him to the car.

[Matías]: I have the image of being inside the car, sitting in the passenger seat, my dad very serious, like talking to me, explaining to me that something important was going to happen any day.

[Daniel]: His parents had separated shortly before, and Matías was expecting more bad news from adults. Although coming to get him at school, out of nowhere, to tell him something important… it could well be another of his jokes…

[Matías]: And I thought he was going that way, and at that moment he says, “Well, Matías, I have to ask you to know this… keep it a secret, you can’t tell your classmates or your teachers, you can’t tell anyone, but… Superman will be staying at our house.”

[Daniel]: Matías waited for him to laugh.

[Matías]: And I said, “It’s another of my dad’s jokes,” but he said, “No, I’m serious, you can’t tell anyone about this…”

[Daniel]: His tone this time was different. Matías did not know what to answer.

[Matías]: What… what… how Superman… Sup—? Are we talking about the same Superman? Because it was like… how is Superman going to be in the house.

[Daniel]: His father insisted and asked him to believe it: Superman was going to be at his house, and he had to keep the secret. Matías got out of the car feeling confused, not understanding what was happening. The recess bell had rung, and when he joined his friends he didn’t tell them anything. Superman in his house? The Man of Steel? They were going to laugh at him. Or worse—they would say that he was a liar.

But his dad wasn’t lying. Superman was flying towards his house.

We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Our editor, Nicolás Alonso, picks up the story.

[Nicolás Alonso]: We’re going to return to Matías and his father, but let’s go back a few weeks first, to Tuesday, November 3, 1987. Exactly at the moment when the telephone broke the silence in María Elena Duvauchelle’s apartment. A friend of Jaime Celedón, the actress was part of the Teatro Ictus and was on the board of directors of Sidarte, the actors and actresses’ union in Chile. When she answered, she heard Lili, the secretary. The fear in her voice was evident.

[María Elena Duvauchelle]: She tells me, “I just walked into the union office, and a death threat was put under the door.”

[Nicolás]: A letter had been passed under the door. María Elena asked her not to leave the place for anything in the world, and she dialed the telephone number of a lawyer from a human rights organization. She had experience receiving threats. A few years earlier, when she was about to start a show in the hall she had with Julio Jung, also an actor and her then-husband, a call had announced that there was a bomb in the place.

That day, part of the box office sales was for a poor district in Santiago, and the public came from there at the invitation of a priest. The police found a package under the stage and defused it, or so they said. She felt that that bomb, real or not, was intended to send a message.

[María Elena]: Of course. At that moment you felt tremendously scared that it would happen, that the thing would explode. But afterwards, it makes you extremely angry and it gives you enormous courage to face them, because you realize how they try to scare you, how they manipulate you. So you find yourself torn between fear and fury.

[Nicolás]: Ever since the dictatorship began, theater and art in general had been persecuted. University theaters had been shut down; actors had been imprisoned and tortured. Some went missing. But some companies had decided to resist, and the Teatro Ictus was one of them, meeting almost clandestinely at first, and later staging works that the military did not understand but the public did, to avoid reprisals. They were often followed by suspicious cars when they left their performances. Actor Nissim Sharim twice had explosive devices thrown at him twice in the courtyard of his house. A mortuary wreath had been sent to María Elena and Julio Jung at their apartment. Or sometimes they would answer the phone and hear bursts of machine gun fire. Someone had burned down the tent where Jaime Vadell, a former member of the group, where performed his shows. The regime did not admit they wereit behind these attacks. And, of course, the perpetrators were never found.

This time it was a letter, with a death sentence and a deadline. As soon as she arrived at the actors’ union, María Elena read it in silence.

[María Elena]: As of this date, October 30, 1987, the following figureheads of international Marxism have one month to leave the country.

[Nicolás]: Below, a list of 25 names and six theater companies. In total, 78 people. At the bottom of the page, a slogan:“for an art and a culture free of foreign contamination,” and a drawing: a man’s gagged face, with the sight of a gun pointed right between his eyes.

María Elena understood immediately what it meant.

[María Elena]: My world turned upside-down because I couldn’t understand that… that if we didn’t leave the country… that is, we would be dead.

[Nicolás]: The letter added one last threat: any leak to the press would be severely punished. It was signed by the Commando 135 Acción Pacificadora Trizano, an organization they had never heard of before. They thought that it could be a faction of the CNI, the National Intelligence Center, the brutal intelligence agency of the regime, a quite logical suspicion that, given the circumstances, was very difficult to prove. Furthermore, that year, several “commandos” of uncertain origin had threatened and kidnapped social and political leaders of the opposition. What was clear was where the name came from. It was a reference to Hernán Trizano, a former soldier who at the end of the 19th century had led a feared group of gendarmes in the south of the country, dedicated to persecuting indigenous people, bandits, and deserters from the Pacific War. A guy accused of applying the “law of flight,” that is, releasing prisoners and then executing them from behind.

[María Elena]: I said, “We won’t leave.” So, we needed to call people, call a psychologist…

[Nicolás]: Someone to help them process what was happening.

[María Elena]: Please. I mean, because logically, some will get very scared, and will want to grab a suitcase and leave.

[Nicolás]: Many, in fact, had already lived in exile before, and had just returned. María Elena had been in Venezuela for ten years. In 1976, while on tour in that country, the regime had declared her, her three siblings and her husband, all actors, a danger to state security. By 1984, when they were allowed to return, the military was still killing opponents in broad daylight. The actors had been organizing for years. In the most difficult moments, the Teatro Ictus had a system of caregivers. If someone had a show, others would wait for him at the exit. And if something strange happened, they notified the union, which according to María Elena, already had some 300 actors, actresses, playwrights and technicians.

[María Elena]: What happens is that the military were afraid of the theater because the theater wakes you up, opens your mind, makes you think.

[Nicolás]: In an attempt to gain both domestic and international legitimacy, Pinochet had announced that a plebiscite would be held in October 1988 to determine if his dictatorship would remain in power for another eight years. He had tight control over information, the terror of the CNI, and he was sure of a victory. But protests in the streets were getting bigger and bigger and so was the pressure from human rights organizations. And the United States, which through the CIA had supported his coming to power, had by then distanced itself from the regime.

Actors were participating in almost all the great protests and cultural events against the dictatorship and additionally, in those years several had become very famous. Not because of their theater plays, but because of something more mundane: since it was almost impossible to make a living from theater, they had begun to appear in some soap operas. They were very light shows, but people loved them. They laughed, they cried with them… they were almost a part of their intimate lives. And then they saw those same actresses and actors in the news, in the tumult of some protest, shouting that Pinochet was a murderer.

Shortly after the letter arrived, the actors began to meet at the union office. Among the companies threatened were El Riel, Grupo Q, El Telón. They knew that if the Commando Trizano killed one or two actors or playwrights, it would be enough to terrorize the country. But despite their fear, they decided to resist. Many people were risking their lives to restore democracy, and it was their turn. So they filed a request for judicial protection, although it didn’t mean much at the time, and they set up protection groups for those were threatened.

[María Elena]: They began to arm themselves—five or six who took turns taking care of different actors who were the ones who were, quote-unquote, most in danger.

[Nicolás]: The most exposed, because they appeared on the list with their first and last names. Among them was the president of the actors’ union, Edgardo Bruna. María Elena’s name did not appear, but that of her husband, Julio Jung, did. About that time they decided that they would hold a press conference so that people would know about the death threats, and that they would start reading a message in plays throughout the country. And more importantly, they would wait for the appointed time at a public cultural event. If they were going to resist, they would do it together, no matter what. When night fell on November 30, the day of the ultimatum, they would be there, waiting for it.

But one thing was essential: they needed to have the greatest possible number of eyes possible looking at that stage. All the eyes of the world. So they started calling actors’ unions in other countries to tell them what was happening in Chile. And soon they began to receive responses, from everywhere.

[María Elena]: Faxes from actors in different parts of the world began coming in. From Germany, from Italy, saying that they were with us…

[Nicolás]: Many had a friend somewhere that they could call. And the union phone kept ringing back. One day they talked with Robert Redford, another with Robert DeNiro or with Jane Fonda… María Elena remembers how strange it was to find herself overnight with figures of that caliber on the other end of the line. They said they were there with them, they promised to denounce what was happening… although in a country like Chile, where people were kidnapped and disappeared, perhaps that alone was not enough. They needed something more convincing.

Then María Elena thought of the writer Ariel Dorfman, one of the most important playwrights in the country. He lived in North Carolina, after being expelled from Chile for a second time. He wrote columns for the New York Times and had a few more than famous friends in the United States.

Maybe he could help them make some noise.

[Ariel Dorfman]: The Chile of 1987. That Chile was a hotbed of terror and hope. The dictatorship was engaged in repressing as much as it could, precisely in order to control the plebiscite, which was a kind of trap they had gotten themselves into.

[Nicolás]: This is Ariel Dorfman, who had been exiled for ten years after the coup. He returned to Chile for a time in 1985, but in 1987 he was expelled again, after denouncing abroad the murder of photographer Rodrigo Rojas de Negri, a friend of his from exile. His murder was one of the most heinous crimes of the dictatorship: He, along with a young woman, were doused by soldiers with gasoline and set on fire in downtown Santiago, then left to die in a vacant lot.

Ariel got involved in the efforts to try to save him and help his mother return from exile to see him before she died. He later denounced the crime in media such as The Washington Post, and confronted the Chilean ambassador to the United States on television. When he tried to return to the country some time later, he was imprisoned and then expelled.

That November morning in 1987, he was in his office working on a script when he got the call from the actors’ union.

[Ariel]: María Elena said they were very scared and very determined not to leave. There is that feeling that yes, this is going to happen, they are going to kill one, then they will kill another. So they said, “No, come kill us all, we will all be here, in the same place.”

[Nicolás]: María Elena told him that they were determined. But they needed all the spotlights in the world to be pointed at that stage.

And for that, they already had an idea in mind…

[Ariel]: And she said, “Ariel, we are going to do a big act on the 30th to say that we are not leaving. If you can find a celebrity, a prominent person, a star… it would be very, very good for us. We are trying to do the same in Spain, in Argentina, in various other parts of the world.”

But they didn’t want these people to just send a greeting and nothing more. They wanted them to dare travel, that night, and resist with them. Ariel thought it was a great idea.

[María Elena]: And Ariel automatically tells me, “Well, we have to talk to someone famous. So, of course… I’ll call you,” he says. Click.

[Nicolás]: Ariel weighed the options. During those years, he had made a lot contacts among American actors and actresses. He thought of Meryl Streep, for example, even though she was filming in Australia. Also of Jane Fonda… but it wasn’t that easy, either. Take a plane, fly to a very dangerous country, wait for an ultimatum alongside 78 people who were sentenced to death. It was crazy, but he had to try. He got the New York Times to book an opinion column in order to denounce what was happening, and he called many actors. Everyone promised to raise their voices, to lend support… but of course, getting on that plane was another thing…

It was the poet and activist Rose Styron who first mentioned it: What if it was Superman who traveled to resist alongside them? Wouldn’t that be perfect? Who could attract more spotlights than the Man of Steel himself?

[Ariel]: I don’t know if the idea of bringing Superman came up in the first conversation I had with her, or afterwards. It’s a matter of… because you had to look for someone from the absolutely most popular culture that could exist, right?

[Nicolás]: Superman. That is, Christopher Reeve, one of the most famous actors in the world at that time. The poet was not a friend of his, but she was a friend of Margot Kidder, the actress who had played Lois Lane in all the films of the saga. If the idea of taking a Hollywood actor to Chile in the middle of a dictatorship was difficult, taking Reeve, only four months after the premiere of Superman 4, seemed like a delusion. But it was worth a try.

[Ariel]: He was imposing, tall, handsome, a beautiful person… if he went there and stood next to them, he could save these actors’ lives, right?

[Nicolás]: A few days passed, and the phone rang again in Ariel Dorfman’s office. It was Margot Kidder. And she was aware of the plan.

[Ariel]: “I’m going to talk to Chris,” she said. “I think he’ll go, because he’s brave, because these things matter to him, because he’s bold and because it’s an adventure, right? Because that’s the kind of person he is.”

[Nicolás]: Reeve, at 35, was known to have an adventurous spirit. He flew planes, rode on horseback, played ice hockey. And he was very involved in social activism: He supported foundations, sometimes he gave talks on social problems, or he went to hospitals to see children whose last wish was to meet Superman. He hadn’t had an easy year; he had split from his partner, and Superman 4 had received very poor reviews, but he had a reputation as a good guy and was a very active member of the American Screen Actors Guild.

If he agreed to go, his voice could speak for many more.

The call happened on the morning of November 22.

[Ariel]: And I hear Superman’s voice on the other end, right? Which I recognized immediately, and he asked me to explain the situation.

[Nicolás]: Reeve had read Ariel’s article in the New York Times two days earlier. Ariel told him about the letter, the Commando Trizano Commando, the ultimatum.

[Ariel]: The conversation lasted about half an hour. And he asked me, “Well, how dangerous is Chile for me, if I go?” And I told him, “Look, I can’t give you the slightest guarantee that they won’t kill you.”

[Nicolás]: That was true: they had no way of knowing what could happen.

[Ariel]: We cannot assume the dictatorship has any rationality. They’re just crazy people, you know? A group of the secret police over there might think on their own that it is best to kill you and attribute it to a leftist commando.

[Nicolás]: Reeve asked another question:

[Ariel]: “And if I go, how would that help my Chilean colleagues?” And I said, “If you go, you can save their lives.” And look, I remember it like it was yesterday, really. There were like three or four seconds of pause. Silence. And he says, “Then I’ll go.” He was going to go.

[Nicolás]: Ariel was shaking with excitement. As soon as they hung up, he began looking for plane tickets and making arrangements for Amnesty International to support the plan. But it wasn’t long before the phone rang again. Reeve wanted to ask him something he had taken for granted: whether he was going to accompany him. I mean… he had invited him. But Ariel had just been expelled from the country. If he tried to enter with him, it would overly politicize a trip that should be seen for what it was: an act of solidarity from actor to actor. He couldn’t go with him… and Reeve couldn’t go alone, so the plan fell apart before it started. But his wife, Angélica Malinarich, a teacher and social worker, had been listening to all the conversations at the office…

[Angélica Malinarich]: I told Ariel, “Look, this poor guy, he can’t go alone, someone has to accompany him.”

[Nicolás]: She told him that Reeve didn’t even speak Spanish…

[Angélica]: That he had no idea what was happening in Chile politically or the brutalities… really. He knew, but facing it is not the same… facing the Chilean reality, which was crazy.

[Nicolás]: He needed someone who knew the country, the methods of the regime, and who would protect him from being used for any other purpose.

[Angélica]: I was not going to defend him; you will understand that I am 1.50 m tall, and thin (laughs). So I told Ariel, “Look, I’m not going to physically defend Superman, but I can guide him, because I know the traps that exist in Chile.”

[Nicolás]: Angélica knew how to stay calm when things got ugly. In 1973, while Ariel was in hiding for having worked for the overthrown government of socialist Salvador Allende, she had been in charge of recovering his literary drafts and making his political papers disappear. She had brought them out of her study in a vegetable cart. One afternoon, when she was leaving the house where he was hiding after visiting him, some policemen in plain clothes had put her in a van to question her, and she had convinced them that she went there to give private lessons to children.

Accompanying Reeve was a risk, yes… but it wouldn’t be the first.

They bought the tickets for the night of November 29. That way, they would arrive in Chile on the morning of Monday the 30th, the day of the ultimatum. María Elena remembers well the moment when Ariel called to tell them the news.

[María Elena]: A marvelous feeling of… As we were just saying, having no less than Superman saving us is something to laugh about a little, do you understand? Because in the middle of all these tragedies, humor is very important, you see, to be able to go through this thing. Without humor, you’re screwed.

[Nicolás]: At the union, everyone was celebrating.

[María Elena]: There were people who cried and people who laughed and shouted, “Damn, wonderful, wonderful.” It was a relief for us to have someone backing us up that day.

[Nicolás]: And with Superman on his way to Chile, the news was going to come out in the media around the world. Ariel told him that it would be his wife, Angélica, who would accompany him. And he would stand by the phone in case the alarm had to be raised to human rights organizations or to the embassy. And in recent days, several US Congressmen had contacted him.

María Elena told him that actors Germán Covos and Fernando Marín, from Spain, would also come, as well as Michael Leye, from West Germany; Raúl Rizzo, and Patricio Contreras, from Argentina, among others. And they would bring letters signed by thousands. They were going to resist right along with them, and that solidarity thrilled them.

They felt that there would be many more than 78 on that stage.

Angélica took a flight from Morrisville, North Carolina. Reeve would fly in from New York. They would meet in the VIP lounge of the Chilean airline LAN, at the Miami airport. Angélica was nervous. The trip had to be as discreet as possible, but it was an absurd idea. How was she going to hide Superman on a plane? She would have to deal with that… now she was worried that it was getting close to departure time and Reeve hadn’t shown up.

So she decided to get on the plane. They were in first class, of course.

[Angélica]: Because you couldn’t send him in economy class, where I don’t think his legs would have fit between the seats, anyway.

[Nicolás]: When she got to her seat, she saw that the seat next to her was empty.

[Angélica]: I sit down… and that’s when he comes in.

[Nicolás]: Reeve saw that she was the only woman alone in first class and asked if she was Angélica. He then sat down next to her, at the window. She was not a fan of Superman, and she was used to hanging out with famous actors and writers. But Reeve, measuring 1.93 m, seemed an imposing man.

[Angélica]: I was impressed by how tall he was, and those beautiful eyes, light eyes, very pretty. I don’t know. There was something very impressive about his presence.

[Nicolás]: At first, he said he was tired, and Angélica tried not to bother him. But Reeve was a pilot, and because of this he had a habit of not sleeping on flights. He told her he was hungry and they ordered food.

[Angélica]: They brought us the food, and imagine all the flight attendants had huge eyes, wide open. I couldn’t really eat much because he started asking me things, little by little. What was happening in Chile, how did I see it, who were these actors?

[Nicolás]: Reeve wanted to know everything about the 78 people who were threatened—who they were, what kind of theater they did, why they were persecuted. And he also wanted to know where he was going to stay the night he would spend in Santiago.

[Angélica]: I told him, “Look, the only thing they have told me is that it’s a very safe place, because the only thing Ariel and I requested was that it had to be a place with maximum security.“

[Nicolás]: They spent a good part of the trip talking. Despite his worldwide fame and the effect he had on everyone who passed by, to Angélica he seemed like a very normal guy, without any air of superiority.

[Angélica]: He was a person, how would I say, very much like any other human being. Speaking with him, you felt that he was a regular person and not a star, or a well-known person or anything.

[Nicolás]: The crew was so ecstatic with his presence that they brought breakfast only for him and forgot about Angélica’s. Before landing, the flight attendants went to get him and took him to the cabin. The captain wanted him to watch the landing with him.

Once on the ground, they were taken into the airport through a special access, so that people would not come at them. Reeve had only one piece of hand luggage; he would spend that day in Santiago that day and fly out the next day. But Angelica was going to stay for a week, so she had to wait for her suitcase. It was inevitable that, in that time, all eyes at the airport fell on them.

That was the situation when Angélica saw two police officers wearing plain clothes walking in the crowd, towards them. When they arrived, they spoke directly to her.

[Angélica]: And they tell me, “We want to talk to the… gentleman.”

[Nicolás]: Angélica was nervous.

[Angélica]: I say, “What for?” “Well, there are things we have to ask him.” “OK, I’ll go with you.” And he says, “No, no, you can’t go in. He has to go in alone.”

[Nicolás]: She followed them through the airport until they entered an office and closed the door. She tried to see what was happening inside, but the dark glass kept her from seeing anything. Putting the ear to the door didn’t help, either.

It’s easy to imagine what must have been going through her head at that moment. Her mission was to get him out as unnoticed as possible and put him in the car where the actors were waiting for them outside. But they hadn’t been in Chile an hour, and there was Christopher Reeve, locked up with two officers in plain clothes questioning him. Angélica had been unable to avoid the first trap. Perhaps the plan wasn’t going to last long after all.

[Angélica]: And time passed. I don’t know, look, it could have been five minutes, it could have been half an hour, but it seemed long. Then the door opens and he comes out. “Thank you very much, sorry for the inconvenience, sorry for the delay.” They always excuse themselves, then they do everything they do.

[Nicolás]: Angélica waited until no one could hear them.

[Angélica]: So, I say, “Chris, what happened?” And he tells me, “Nothing, they wanted to talk about me, about my movies.” Can you imagine? “About my movies?” They wanted to take pictures with him.

[Nicolás]: That’s why they had taken him to a room for interrogation.

[Angélica]: Look at the madness, look at the madness—everything that was happening on the other side, outside the airport and in the city, and look, look at these people doing that. That is the madness of Chile.

[Daniel]: The madness of Chile. And they were just arriving.

We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, we heard how actor Christopher Reeve, famous throughout the world for playing Superman, took a plane to Pinochet’s Chile. The plan was for him to accompany a group of 78 theater professionals threatened with death. With him was the Chilean Angélica Malinarich, with the mission to make his stay in the country as safe as possible.

The deadline set for them by the Commando Trizano Commando expired that same Monday, November 30, but they were going to resist in a massive act.

Nicolás Alonso continues the story.

[Nicolás]: Leaving the airport was not so easy: some media had published the news of his arrival. The newspaper La Época had headlined “Superman arrives on Monday,” and a crowd of people was waiting for him. Reeve gave a first statement in English before the camera of TVN, the state channel, but his words were not translated in the broadcast.

They made their way through the people to the car where María Elena Duvaucheulle was waiting for them, with her husband, actor Julio Jung. They had been parked there for a while, waiting, and other actors were waiting in other cars. The idea was to advance in a procession, in case something happened to them on the way.

María Elena waited anxiously for them to appear.

[María Elena]: And I see this tremendous rooster… how handsome he was, extremely handsome.

[Nicolás]: Reeve knew from Angélica and Ariel who she was, and he gave her a big hug. He told her that being there, accompanying them that day, meant a lot to him.

[María Elena]: And that he was very excited about this, but something like, let’s go to the fight. See? Fantastic.

[Nicolás]: For the time being, they would go to the fight in a small Mazda where Superman could barely fit his legs, but they got him in as best they could. Reeve kept asking questions. He wanted to know more about the things he had been told: the actors persecuted by the dictatorship, the threats, the murder of Víctor Jara, who, besides being a singer, had been a great theater director. Angélica served as translator. The demonstrations had already begun. They had made a protest in front of the Municipal Theater, and some actors had made T-shirts with a drawing of a target and the phrase “Shoot me first.”

That’s how they arrived at María Elena’s apartment. Angélica wanted to know where the maximum security place was, where she had been told they were going to stay. And María Elena said that, well… that what they had at the moment was the house of actor Jaime Celedón. That they would be fine there. Jaime had recently separated from his wife, who had moved to live with their children, so it was only him, with an empty house. It even had a pool!

Angélica listened to her, trying not to grimace.

[Angélica]: So I say, “Well, and what guarantee is there that the house of an actor, who is also threatened” (laughs), “can be a guarantee?” She says, “No, because look, nobody knows, almost nobody knows where his house is.” “I don’t know,” I said, “well, what can you do.” OK, as we say: “We are going to plow with the oxen we have.”

[Nicolás]: Moreover, they had to get moving. The press had been summoned to a conference in the Comedia Room of the Ictus Theater, right across from María Elena’s apartment. The idea was for Reeve and the other international guests to speak. They had to start making noise. The ultimatum deadline was that same night, and it was vital for people to know that Superman and the others had come because they were on their side.

That same day, Apsis magazine, one of the few media outlets that still dared do independent journalism despite the regime’s persecution, had published a full-page question: “Why is Superman really here?” On the other side of the spread, a huge cartoon showed the superhero of the comics, dressed in his suit and cape, flying with Pinochet in his arms.

Reeve was not amused by the joke. This was no comic book, this was real life… and everyone was in danger. This is Ariel Dorfman:

[Ariel]: He didn’t like it much, shall we say. He said, “This is very serious, this is not, not a joke, right?” But it’s funny that… what did Superman come to do? To take away the dictator.

[Nicolás]: There were at least a hundred people in the room, maybe more. The place was packed. At a table with microphones on the stage, Reeve, the other international guests, the president of the union, Edgardo Bruna, Angélica and María Elena sat facing journalists from various agencies. Angélica looked around the place.

[Angélica]: To check whether the emergency exits were working, all those things, because it could have been dangerous in there, but I wasn’t going to tell him that.

[Nicolás]: Tell Christopher Reeve. María Elena watched the people who were in the theater. There were journalists, actors, onlookers… and also a group of CNI agents by the stairs, or so the union suspected.

[María Elena]: We were worried, worried that they would come out with some… someone would be shot, I don’t think him, because it would have been terrible. Or some actor or someone who got out of hand and the guys were there. It could happen.

[Nicolás]: The atmosphere was very tense when the conference started. Among the local media was Cooperativa, one of the few radio stations opposed to the regime that remained on the air. This is a recording of what Reeve said that day. Next to him, you can hear Angélica translating his words.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Christopher Reeve]: I think it’s important to add that I’m not here on a political basis at all. I’m here as actor to actor, worker to worker, friends to friend. All our concern, I think, in Spain, in Germany, in Argentina, in England is on the human rights issue that no actor, no performer should ever have to live under these kind of threats. (Applause)

[Angélica]: Should I translate it? OK. He wants to make it clear that he does not come here on a political basis; he comes as an actor to show solidarity with the actors, as he says, from actor to actor.

[Unknown person]: From brother to brother.

[Angélica]: From brother to brother, did you say that? from brother to brother?

[Reeve]: That’s right. From worker to worker.

[Angélica]: From worker to worker, from brother to brother. And that no actor should work in these threatening circumstances.

[Nicolás]: Reeve wanted to make clear his admiration for Chilean actors.

[Reeve]: We all share admiration for the courage, the incredible courage that these 77 actors and these seven groups are showing under this kind of… this kind of threat.

[Angélica]: That they admire the courage of these Chilean actors, who, as you said before, continue to work under these circumstances.

[Nicolás]: Reeve read a letter he was carrying from the American actors, and then a guest from Germany spoke and another from Spain, who recounted that his union had sent a direct telegram to dictator Pinochet’s office, holding him responsible for anything that might happen that day. And he said that they were there, accompanying their Chilean colleagues, as the Chileans had supported them before, when they had been persecuted by Fascist Spain.

[Angélica]: Chris was the only one who had never experienced a dictatorship or whatever.

[Nicolás]: All the others, or their parents had survived some tyrant.

[Angélica]: They were people… of course, they weren’t naive in that sense, like Chris was, who couldn’t believe that someone would take away their rights or something.

[Nicolás]: When it was all over, they had lunch at a pizzeria and then went to Jaime Celedón’s house. They had chosen it because it was spacious and in a well-off area, but also because it was three blocks from the United States embassy. Many years later, Jaime would write in his memoir that even the ambassador called him to request that he accommodate him.

The actors had set up their own system of bodyguards. Four were posted outside the house day and night, to protect Reeve. While he settled in Jaime’s room, who moved to another room, the actors gathered in the living room. It was almost six in the evening, The ultimatum was just a few more hours away. The act of resistance, which they had called “Art and Life,” would be at eight o’clock at the Nataniel Stadium, a basketball court in downtown Santiago.

Everything was quite uncertain, although they had already paid the rent.

[Angélica]: A lot of phone calls, a lot of news, someone came and said, “Look, there is no green light for now,” because something was happening. You could sense that the actors were nervous, because just picture it, everything depended on that.

[Nicolás]: That they were all together, in one place, that night. Hours earlier, an anonymous call had alerted the union that a second letter was arriving. Then an envelope appeared under the door. It said, “The deadline to leave the country has passed. Now you will have to face the consequences.” And they warned that someone from the list was going to pay for not having heeded the order not to reveal the threats. The new list included three additional actors, and the names of five young people who had been disappeared by the regime around that time, which were covered with a bloodstain.

Angélica was scared, but she didn’t want anyone to notice. It was something she had learned since the coup d’état—you had to control your fear, always. So that no military could sense it. Although they joked around and cheered each other up, they had no idea how the night would end. The plan was to respond to death threats with an act celebrating life. Some guests would read poetry; others would sing or dance.

Still, they knew things could get ugly.

[Angélica]: The CNI, all the soldiers could arrive with machine guns or with whatever, or all these crazy groups that were on the loose could also arrive, or they could kill us with bombs or fill us with tear gas and in the middle of all that, nobody knows who is shooting at whom.

[Nicolás]: But there was no time to back down. Angélica was told that a car was coming for her and Reeve, and she braced herself for anything.

Angélica sat with Reeve in the back seat. In the front were a driver and a security guard. They had explained to Reeve that there could be rioting, and that if tear gas was fired, he was to bite into a lemon and cover himself with a scarf, so the effects would not be so bad. Around the stadium, they could notice that the atmosphere was agitated.

[Angélica]: There were a lot of people outside, there were a lot of police officers outside… with machine guns…

[Nicolás]: And they started getting nervous.

[Angélica]: The driver said: “Hmmm-hmmm. Let’s stop.” So we stopped almost in front of the stadium. Right where we stopped, there was someone waving at us.

[Nicolás]: It was another person in charge of the actors’ security. The man told them that the stadium was completely blocked by the police. They couldn’t get through. At the last minute, the Ministry of the Interior had canceled the permit for the event, despite the fact that much of the public had already been inside for two hours. So the man asked them to move a few blocks away from the stadium and wait in the car while the threatened actors decided what to do.

When the car stopped, the person with them who was in charge of security got out to talk with three others who got out of another car that was coming from behind. They carried walkie-talkies to communicate with the other guests. Angélica tried to listen, but she didn’t want Reeve to get out of the car.

Meanwhile, outside the stadium, María Elena and the president of the union, Edgardo Bruna, continued to press for them to be allowed into the stadium. Then the riots started.

[María Elena]: And that’s where the tear gas begins. And everyone was yelling, “To the garage, to the garage, to the garage.”

[Nicolás]: To the Matucana Garage. A car garage converted into a counterculture space, where bands played and parties were sometimes held. There was room, hopefully, for about a thousand people, but there was no time to think of another place. It was about 30 blocks from where they were, and the actors and the public were already marching there, amid the tear gas.

A few blocks away, in the car, Angélica looked anxiously at the security men. Then one of them approached and informed her of the change of plans.

[Angélica]: I ask him, “What is the Matucana Garage?” He tells me, “Well, it’s a garage with a single entrance, with a single exit, with no windows. In other words, you go in through the door, the only door. The only opening. And at the end, over there, was the stage.

[Nicolás]: Angélica was frightened. And she understood that she had to be honest with Reeve, who was looking at her without really understanding what was going on. So she told him:

[Angélica]: “Chris, this is a situation where you are going to have to decide what to do. This place is very risky.“

[Nicolás]: She explained that there were no windows or emergency exits. Nothing.

[Angélica]: “Anything can happen here. And I don’t want to make the decision for you. So you are the one who has to decide. And I tell you again: the risk is high.”

[Nicolás]: Reeve thought about it for a few seconds and asked her:

[Angélica]: “What about the other artists who are participating? Are they going?” And I say, “Yes.” “So I’m going too,” he said. And I asked him, “Are you sure?” “Yes, I’m sure. Let’s go.”

[Nicolás]: So the car took off, amid the tear gas, the police and the crowd.

[Nicolás]: The entrance to the Matucana Garage was in chaos. A crowd of people was piling up in front of the door, trying to get in. A block further down there was another protest, and the tear gas made the air unbreathable. From the car, Angélica and Reeve heard the dry burst of gunfire, and the voices of thousands of people who chanted a phrase that was heard in all the protests against Pinochet: “And he will fall, and he will fall.…”

Angélica and Reeve looked at the garage entrance, which made him think of a hangar to store aircraft, in pieces. Angélica didn’t know what to do. She hadn’t wanted to part with Reeve since they got off the plane, but she wouldn’t be able to do anything for him inside. Some actors were crying. Reeve thought that if he went in, he was never going to come out of there, but the union president tried to reassure him. He said that he would be safe with them.

Angélica tried to think clearly, to understand her own role in that extreme moment. There was a gas station in front of the garage. It had a pay phone. If something happened, maybe she could call collect to the United States.

[Angélica]: So I said, “At least I’ll call Ariel right away and he’ll sound the alarm immediately, or I can call the embassy so they can do something a little faster,” right?

[Nicolás]: She explained her idea to Reeve. She wouldn’t gain anything by going in with him; there were actors there who would protect him much better than she could. He asked if it wasn’t too dangerous for her to be out there alone, waiting, but she told him not to worry about her. Besides, she would be with the driver. So she walked over to the other actors and handed Superman over to them. “Colleagues, please…”, she said, and that was all she needed to say. Six bodyguards grabbed Reeve and, pushing their way through the crowd, hauled him into the garage. When he entered, the explosion of the public left him speechless. Never before had he been welcomed with such intensity, such applause, shouts, euphoria and tears.

María Elena remembers him scared at that moment.

[María Elena]: Very scared, because he went into a hangar knowing that the police were outside and shots were being fired and who knows what. In other words, he didn’t go into a theater, no—he went into a hangar. A semi-dark thing, too—awful, you had to hang lights and things… because… just forget it.

[Nicolás]: Angélica couldn’t find any coins for the pay phone, but she convinced the gas station attendant to lend her one. She requested a collect call and called her husband, Ariel Dorfman, in the United States.

[Ariel]: She told me, “He’s inside and I’m here waiting, because if something happens to him, I have to tell you so you can tell the world, all right?”

[Nicolás]: She told him about the tear gas, about the police outside.

[Ariel]: I didn’t know if she was going to end up going in there to talk to him. I didn’t know if my wife was going to die, if my new friend was going to die. If all my theater friends would die, too.

[Nicolás]: Ariel stayed anxiously glued to the phone in his office. There was nothing else he could do. Angélica asked the driver to leave the car at the gas station, and she sat inside, waiting. There was nothing else she could do, either.

[Angélica]: So for me it was a wait, an eternity, in that car. I know it was a long time there. It was long.

[Nicolás]: It was starting to get dark. In the garage, some two thousand people squeezed onto the floor and climbed on the pillars that supported the roof. The heat was tremendous and there was little air, but no one moved. After what had happened at the stadium, the actors were angry. The police were out, they had disobeyed their orders, and people were still chanting against the regime. As a teenager, Reeve had accompanied his father, a teacher, to some protests in the United States, but this was something different.

He had been seated on the stage with the other guests and several threatened actors, when the lights went out. Or someone put them out. Then the people were silent for half an hour, while they tried to fix it.

Only when it came back, amid the shouts of the public, did the acts begin. The guests went up on stage, one by one. One sang a song by Víctor Jara, another recited a poem, another gave a speech. There were rock groups, artistic performances. The actors answered questions about the threats and the meaning of being there that day, and the guests read messages of solidarity from actors and directors from around the world.

The clandestine news program TeleAnálisis, which was distributed from hand to hand on VHS, was the only outlet that recorded part of the act. The images show a serious Reeve, night falling. An actor translates for him in front of the camera:

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Christopher Reeve]: I’m here to show support to the threatened actors of this country.

[Actor]: He comes to show solidarity with the actors who are threatened.

[Nicolás]: Then the actor reads a letter that Reeve brings from the United States.

[Actor]: You have our support at this difficult time that the Chilean people are experiencing, and receive our admiration for the creative work you continue to do under conditions of threat and pressure. And here are the signatures, a great many…

[Reeve]: And it is on behalf of 38 thousand American actors.

[Actor]: And this is supported by 38 thousand American actors.

[Nicolás]: Reeve smiles and makes a small bow in front of the journalist, before returning to the stage with his companions. María Elena remembers him being suffocated by the extreme heat, but moved by what he was experiencing. He was very intent on talking with the artists and people from the public who went up on stage.

[María Elena]: I think that Christopher has never forgotten that moment. Only in movies could he have lived it. People who, suddenly one sang, another told him he was proud to have him here in this country.

[Nicolás]: The actors translated for him and he would give an opinion, ask a question, but he wasn’t the center of attention, either. As the time for the ultimatum approached, people continued to talk and sing, and the fear subsided. They were together and that somehow made them feel safe, as safe as they could feel in that Chile. Some applauded, others laughed. The vibe in the air was not one of terror. At one point in the evening, Reeve read his letter and said a few words, but what he said was recorded only in the memory of those who were present.

[María Elena]: That for him this was really important in his life. The fact of traveling from such a distant country, so many hours of travel to show solidarity with the actors, with the playwrights, and for him this was like an honor, despite the circumstances, despite what we were living through.

[Nicolás]: He also thanked them for that amazing day, and said that he would tell, on his return to the United States, how brave and beautiful everyone there was. It was around eleven at night and no one had come in to kill them. Perhaps because the 78 were in that garage together, with actors from abroad and thousands of people there, supporting them. Or maybe because the purpose of the letter was never other than to instill terror. There was no way of knowing, but something had become clear: They had survived. Fear had not been able to win over them.

Angélica, who had gone to María Elena’s apartment a while earlier, was waiting nervously. Reeve had sent word that he wanted to stay until the end, so she shouldn’t wait outside for him all night. He wanted to continue talking with the other artists, to learn more about their lives. But it was almost midnight. María Elena and several of the guests had returned, and Reeve hadn’t arrived. Time went on, actors kept arriving, and no Reeves. Angélica was getting more and more uneasy.

[Angélica]: And I said, “No, this is not normal, María Elena. What’s going on? Something must have happened to him.” “No,” María Elena tells me, “calm down, nothing’s wrong, he probably stayed behind talking with someone.” But just imagine, he must have been talking to someone. That’s something you say after a dinner party, at a normal meal and in normal times.

[Nicolás]: When he finally arrived, around 12, Angélica breathed a sigh of relief. He had stayed behind talking until almost the end, when there were two or three acts left. He was tired, but he didn’t want the night to end. And, indeed, it didn’t end. He was just entering and they were already serving him pisco, empanadas, sangría. If there was one thing those actors did not lack, that was enthusiasm. And they had just survived the ultimatum. If they didn’t celebrate now, then when?

The night ended late. Angélica and Reeve went with Jaime Celedón to his house, and she could hardly sleep. She got up early to get something for breakfast. She brought Reeve breakfast in his room, and they talked about what they had experienced the day before, which neither of them would ever forget.

[Angélica]: He was very happy, very happy to have had contact with people. That’s what he cared about the most.

[Nicolás]: That morning they drove through the high-end neighborhood and Reeve was struck by the inequality compared to the Chile he had seen the day before. Back at the house, Angélica wanted to let him rest, but that would not be possible. Soon the doorbell began to ring.

[Angélica]: And the children arrive, Jaime’s children and a cousin arrive. Jaime’s wife arrives, who didn’t live there, and the wife’s sister. And I say to her, “Hey, what is this? No one was supposed to come here. Nobody.” “Well, this is Chile, that’s all. What can we do.”

[Nicolás]: One of the children waiting was Matías Celedón, Jaime’s 6-year-old son. He had kept, as long as he could, the secret that his father had told him in the school parking lot—that Superman, his idol, was going to be at his house. But in the end, he had told his best friend. He was extremely nervous. That morning, his mother had picked him up at school and he had found out that it was time: They were going to meet the Man of Steel.

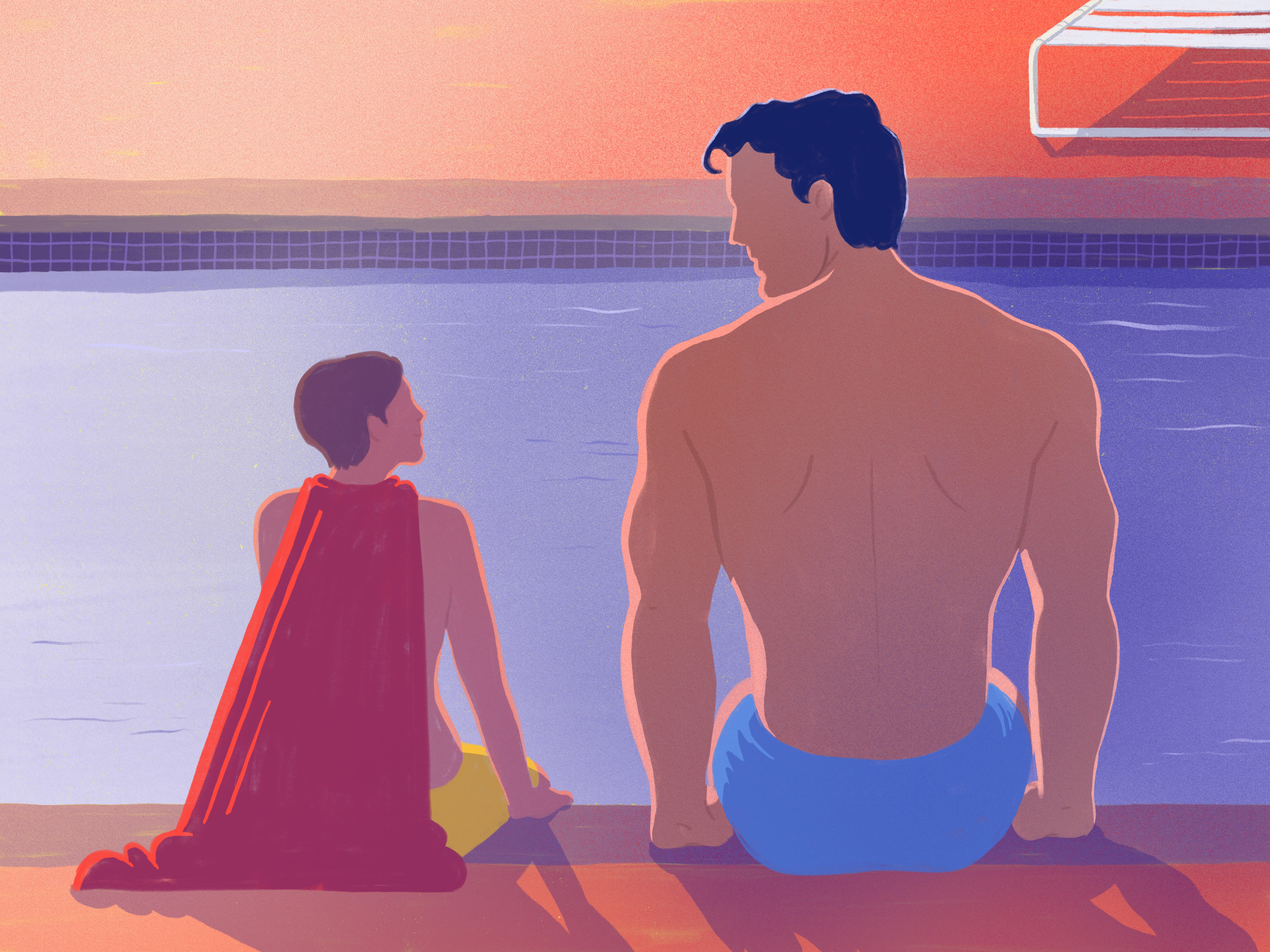

Matías crossed the hall of the house next to his mother, as far as the door that led to the patio. And when he stepped outside, he saw him. It was impossible, but it was true: There he was, sitting at a small table, chatting with his father. They even seemed like friends.

[Matías]: And it was Superman having breakfast, without his cape and without his suit, but he was two meters tall, with a fit body. I mean, it was Superman all right, there in front of me. My dad is 1.65 or 1.70 tall. We were like the hobbits in front of a Viggo Mortensen. He really was a superhero.

[Nicolás]: In addition, he spoke in English, Superman’s language.

[Matías]: And he had an imprint and a special aura.

[Nicolás]: At first he was in shock. Matías says he can still remember what he felt at that moment—a mix of terror and admiration, which left him speechless. As if there suddenly appeared in the middle of your living room… I don’t know… an Egyptian god. But he was brought out of his shock by Superman himself, who asked what his name was. He knew a little English from school, so he stammered:

[Matías]: “Hi, my name is Matías, how are you?” And he said, “Fine, thank you.” In short, a micro conversation in English, which was amazing for me, and in that conversation he told me that he had a son named Matías.

[Nicolás]: Matthew, barely older than him. Matías felt that Superman was entrusting him with a very personal secret, something that did not appear in the comics.

[Matías]: That also humanized him; I said, “Ah, well, Superman has a son.” That was not in the comic, the canon. I mean, as far as I know, Lois Lane never got that far, at least in the movies.

[Nicolás]: Matías looked at him, hypnotized, while Superman talked with his dad and Angélica, the mysterious woman who had accompanied him from the United States. And he wondered why he was dressed like that… like them.

[Matías]: I mean, there’s no suit. If it’s Superman here, he came as Clark Kent, and that was a little more logical. I was like, “Why isn’t he wearing glasses, if Clark Kent has glasses?” But it was more like saying, “Well, here comes the civilian Superman.”

[Nicolás]: Matías must have asked something, because he became convinced of that idea, that Superman had to camouflage himself like that, like one of them, to fulfill the mission he had come for. A mission that no doubt had to do with defeating Pinochet. It made sense, after all. Meanwhile, other children were arriving at the patio and falling into the same state of shock as he had. They were the children of the group of actors closest to his father.

[Matías]: It wasn’t like many children arrived, because the security apparatus wasn’t all that safe. These were actors. In other words, they were probably very good at faking their opportunity to be great bodyguards, but at the end of the day, their skills remained to be seen.

[Nicolás]: Matías remembers the impact he had seeing Superman so down-to-earth, so affectionate. He played with them, told them things about his country, about his life. And he also remembers, of course, one of the most beautiful moments of his childhood, when they got into the pool and he picked them up, at two meters high, and threw them into the air. Matías flew, and while he did, he felt that he was living the movie that he had seen so many times, that he was the boy rescued by Superman from Niagara Falls.

[Matías]: It was like a dream come true. I mean, I’m in the pool and it’s Superman who’s playing with me, throwing me far to fall into the water. That I do remember, like saying, “Wow!” I mean, really impossible things can happen, which I think did have consequences on me even as I grew older.

[Nicolás]: It made the line between the real and the unattainable a little blurrier. Today Matías is a novelist; the real and the fictional are his working material.

When it was time to take Reeve to the airport, they were all very excited. In just two days, they had gone from the initial strangeness of meeting a Hollywood star to something much deeper: They had found a mate.

Now he was leaving, and they might never see him again.

[María Elena]: Whoa… I was very moved. I thanked him thousands of times and in my life he will always remain a wonderful memory. He was an extraordinary guy.

[Angélica]: We hugged. Of course, he had to sort of fold himself in half. I told him, “Have a safe trip.” And he left very happy.

[Nicolás]: Before leaving, he told them one more thing: That he was going to tell everyone, in the United States or anywhere, what he had experienced on that trip.

And he did.

I had leftMaría Elena’s apartment, after interviewing her, when she called me back. When she opened the door, she had a very old cassette in her hand. On its moldy, peeling labels was written Conversations in Exile. A. Dorfman–Chris Reeve. Ariel had sent it to her in 1989. As soon as I had left, she started looking for it among boxes that surely had not been opened for a long time. “It has to come back,” she said, and she handed it to me.

When I digitized it and listened to it, I understood that it was the missing piece of this story. There was Christopher Reeve, there was Superman a year later, giving a public talk and telling all about his trip—what he thought, what he had felt. The audience at the Theater Festival in the city of Williamston, in Michigan, listened to him very attentively, as he talked with Ariel Dorfman.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Reeve]: There was a mob of people outside the entrance to this garage… At this point now there was no way I was going to go home. And the people are screaming and chanting…

[Nicolás]: Reeve told them everything that had happened that day: the garage, the crowd, the machine guns, the chants against the regime, the riots,

[Reeve]: And also the military could just crack down on the whole thing.

[Nicolás]: He told them that it was very important to become aware, as Americans, of their country’s responsibility in Pinochet’s rise to power..

[Reeve]: We created this monster…

[Nicolás]: But, above all, he told them about how much he’d been moved by meeting those actors who lived every day under the sword of Damocles, risking their lives…

[Reeve]: Sword of Damocles…

[Nicolás]: About the intensity with which they acted, sang, recited…

[Reeve]: The sense of solidarity that came to me was something I’ve never experienced before.

[Nicolás]: About the solidarity between them, something he had never seen before. And how they withstood every moment of tension, every blow.

[Reeve]: But these actors… these actors always rebound. They laugh. They enjoy themselves.

[Nicolás]: Those actors, he told them, always recovered and laughed. It was their way of standing up. Of not letting terror ever, ever get the better of them.

[Daniel]: Reeve said that his visit to Chile changed his way of understanding art and his relationship with politics. The following year, he participated in the “Franja del NO,” the campaign to remove Pinochet during the plebiscite. In his message, he reminded Chileans that the vote was secret and the future was in their hands.

[Reeve]: Remember that the ballot is secret, and the future of your country is in your hands.

[Daniel]: Pinochet lost that plebiscite, and in 1990 democracy returned to Chile.

Five years later, in 1995, Reeve fell from a horse and became a quadriplegic. The Chilean actors received the news with pain. They could not accept that someone who had taken this risk for them would have such a tragic fate. Over the years, he was honored in several of their plays and in 2004, in New York, shortly before his death, the State of Chile awarded him the Order of Bernardo O’Higgins, the highest honor for a foreigner. Reeve received the medal in his wheelchair, very emotional, and said that he would never forget those days in Santiago.

Nicolás Alonso produced this episode. He is an editor at Radio Ambulante and lives in Santiago, Chile.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura and myself. Désirée Yépez and Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking.

The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano, with original music by Ana Tuirán.

Our thanks to Radio Cooperativa, the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, and Yerko Yankovic, former cameraman for TeleAnálisis.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Aneris Casassus, Emilia Erbetta, Fernanda Guzmán, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Ana Tuirán, Elsa Liliana Ulloa y Luis Fernando Vargas.

Natalia Sánchez Loayza is our editorial intern. Selene Mazón is our production intern. Zoila Antonio is our audience engagement intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is mixed in Hindenburg Pro. If you are a podcast creator and you are interested in this program go to Hindenburg.com/radioambulante and take a 90-day free trial.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.