The caravan of misinformation | Translation

Share:

► Join Deambulantes. We need to add 1,800 new people to our membership program before the year ends to ensure our stability. With your support we can keep telling the stories that deserve to be told.

►Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

Daniel Alarcón: Hello, ambulantes. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

This end of the year, we’re doing something a little different, which we hope you will like. Some of you already know that we produce another podcast called El Hilo, which airs every Friday. El Hilo is a news podcast, one subject per week, the kind of subjects that are a topic of conversation all over Latin America.

We’re very proud of that podcast, and we think that if you don’t know about it already, you’re in for a treat. It has something in common with Radio Ambulante—well, several things, but mainly, the commitment to telling a good story with characters that help us understand what Latin America is all about.

Last week we shared an episode from Venezuela, and today we have one that is quite important today: about vaccines and misinformation.

I hope you enjoy it and find it useful. Thank you.

Eliezer: Welcome to El Hilo, a podcast from Radio Ambulante Estudios and VICE News. I’m Eliezer Budasoff.

Silvia: And I’m Silvia Viñas.

Eliezer: Today: Who’s behind the false information about vaccines, how they’re spreading it, and what we can do to combat it.

Silvia: We wanted to learn about the groups that spread disinformation on the pandemic and the COVID vaccine. So, we talked to her:

Melina Ccoillo: I am Melina Ccoillo and I work with the Peruvian digital outlet Salud con Lupa.

Silvia: Melina is a Peruvian journalist. And in the same way that a lot of disinformation is spread, Melina began to investigate these groups after seeing a flyer that a colleague gave her.

Melina: A flyer that had come to her through WhatsApp from a friend in Cuzco. And this flyer said, “Do you want to die vaccinated?” I mean, it was something very strong. And images of a lot of people who had supposedly died from the COVID-19 vaccine.

Silvia: It was obvious to Melina and her team that this was misinformation. The scientific community has stated that COVID-19 vaccines are safe.

Melina: It caught our attention, and of course, we worked together to address this subject from different perspectives. But I was the one who followed the issue of who they were, because at the bottom of that flyer we found two groups: Doctors for Truth Peru and the World Organization for Life Peru. So, from there we said, here we have two, but there are probably more, and who can they be? We suddenly had all these questions and we wanted to investigate.

Silvia: To begin her research, Melina checked the social networks of these groups. In other words, what a person would do who sees that flyer and wants to know more.

Melina: I went first to the World Organization for Life Peru, and they had videos where they were showing a gathering of people.

Audio file, Max Castro, General Coordinator, OMV Peru: My name is Max Castro. I am the coordinator of the World Organization for Life.

Melina: This was one of those events they held.

Audio file, Max Castro, General Coordinator, OMV Peru: Important! The information that will be given to you today may change the perspective of what you have thought so far about the current health situation.

Melina: And the one that said, “The fourth caravan for life” caught my attention, I mean, there were already four of these events that they had held periodically throughout the pandemic, right? And for this event, they invited their representatives. From there I also began to write down who some of those people were. This event was held outside a Catholic chapel, in a district considered low-income in Peru, the district of Carabayllo.

Silvia: After presenting his arguments against the vaccine, the most . . . let’s say, enjoyable part of the event began.

Archive audio, OMV Peru member: A bag of bread for you. Very good, gifts! Let’s see . . .

Melina: They gave out bags of bread; I also saw clothes. And the people who went had to be unmasked in order to receive the award.

Archive audio, OMV Peru member: Very good, very good. Let’s see, we have some gifts for a mommy, but without a mask. There she is, who? Who? Who? Let’s see…

Melina: So, I said, where are we, you know?

Archive audio, OMV Peru member: I have seen you very attentive.

Anti-vaccine group member: Attentive and fearless, that’s exactly what we want. Fearless people.

Melina: They talk about the government having a genocidal plan, or power groups that have a genocidal plan to kill the population. But somehow, they were also trying to kill many people who could have been infected there or who were probably already infected at that time. This was in July of this year.

Silvia: In September there was a fifth “caravan,” that is, another event like the one Melina describes.

Melina: Also, obviously, a live event in another district that is also low-income.

Silvia: And also promoted by the World Organization for Life Peru.

Melina: But there were also representatives from other groups. There were also Doctors for Truth, Psychologists for Truth. So I started to see who they were.

Silvia: And so, Melina ended up investigating eight of the main groups that spread false information about the pandemic and the vaccine in Peru.

Melina: Just to mention them, right? The World Organization for Life Peru, Doctors for Truth Peru.

Silvia: The Peruvian branches of two of the most prominent disinformation groups in the world.

Melina: OMPEI, which is the Peruvian Medical Research Organization OMPEI.

Audio file, Rosa María Apaza, President of OMPEI: No, sir.

Host: Don’t they save lives?

Rosa María Apaza, President of OMPEI: The scientific community is corrupt. The goal of the laboratories is not to heal the population, or humanity; it is to make them sick.

Melina: Well, Psychologists for Truth.

Silvia: Another called Citizens for Truth Peru.

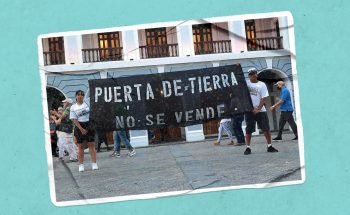

Archival audio, protesters: This fight for freedom, for life, against the health measures that have been imposed on us worldwide! Freedom, freedom!

Silvia: Also, the World Health and Life Coalition, Comusav Peru. Another called Revolutionary Humanist Action.

Melina: And Stop 5G Peru.

Archival audio: Peru does not agree with 5G!

Silvia: Melina tells me that, although their beginnings are different, all these groups have a lot in common.

Melina: I also began to recognize who their representatives were and what connection they may have had with other groups before the pandemic. I saw that some were related, for example, to groups against a gender perspective, groups against women’s sexual and reproductive rights. And now, as a result of the pandemic, they began to spread arguments against the COVID vaccines.

Silvia: Not just vaccines, of course. Some groups deny the existence of the pandemic and say that masks don’t work.

Melina: They promote chlorine dioxide, they promote Ivermectin. They have no scientific basis, but they are promoting it.

Silvia: There are some groups I see on the list . . . This Peruvian Medical Research Organization sounds very official, and serious. What are these groups? Are they some kind of NGO? When we say groups, what exactly do we mean?

Melina: Yes, well, when they talk about organizations, I have seen that they are legally registered. They are legal, right? Formally established. They have offices in Latin America and Europe now. The same in Peru.

Silvia: This is the case of several organizations that Melina investigated, including the group Revolutionary Humanist Action, which started in Bolivia a long time ago and arrived in Peru during the pandemic. The same with Doctors for Truth, which was born in Germany, gained strength in Spain, and has reached Latin America with its disinformation. Stop 5G also exists internationally, with militants in Peru.

Melina: It was an established movement before the pandemic, but with the arrival of COVID-19, they relate it to the fact that maybe we’re being manipulated through wireless signals.

Silvia: Something that I find a bit shocking is that there are doctors in these groups, right? And that doctors even lead them.

Melina: Yes, Doctors for Truth above all; well, in general, most have doctors who spread their theories.

Silvia: Melina spoke with a spokeswoman for Doctors for Truth, Vanny Herrera. She said that her group does believe in COVID-19, but they believe that COVID-19 has not caused that many deaths and that masks are useless. Two false claims. Melina tried to get in touch with representatives of other organizations, but they did not respond. But she tells us that many of the groups she investigated defend themselves publicly saying that they are not anti-vaccine, but anti-experiments.

Melina: But what I was able to find is that most of them spread alternative therapies or work with alternative therapies before the pandemic. Therapies that can cure cancer, for example, do not have scientific evidence. And as a result of the pandemic, they continue with this, and maybe that’s why they refuse to receive the vaccine as a form of prevention. But it does seem striking, doesn’t it? The group Doctors for Truth are doctors, so when people listen to them, they’re going to believe them because of what they say, because of the things they mention. And if you look at the Telegram groups, which is where they mainly spread all their theories, they present the representatives as well-known doctors who have stated this theory, who have spoken about it in different places. So people who may not check whether this is true, are going to believe it at once, and probably spread it to their acquaintances, their relatives. And then this misinformation spreads.

Silvia: What have you found about how these groups are funded?

Melina: Well, what I see mainly, when I contacted the spokeswoman for Doctors for Truth, she told me that they received voluntary donations.

Silvia: The same goes for the Peruvian headquarters of the World Organization for Life.

Melina: What I could see in a Telegram group, just once in what I saw, they asked, well, donations to be able to print their flyers, their posters, so that they could later be distributed to more people.

Silvia: The website of the World Organization for Life says it has received almost four million dollars in donations worldwide. Locally, Melina found that some groups charge for Zoom events, usually between ten and thirty soles, which is roughly between three and seven dollars. And another way of financing is the sale of products. Melina told me what the Global Coalition for Health and Life does, for example.

Melina: They place a lot of ads—people or representatives that are selling chlorine dioxide, right? So that way they can also do some kind of financing.

Silvia: But Melina says there is still a lot left to investigate when it comes to the funding of these disinformation groups. Now, everything else that Melina and her team have revealed has been enough to cause a reaction from these groups. The Salud con Lupa investigation includes the names of people who lead disinformation campaigns. So when the report came out, Melina says she received a series of messages from a representative of Doctors for Truth.

Melina: The spokeswoman, with whom I had already spoken, began to send messages via my WhatsApp saying this was my investigation or they were not doing that . . . In general, I would say they had a threatening attitude. And well, I answered something like, well, there is nothing here that I made up. It ended there at first, but then they started with the insults through social media in Salud con Lupa. When the media published a note about vaccines, we not only have these, but about another, the Sinopharm vaccine, for example, and many here in Peru are refusing to get vaccinated, also because of misinformation given by some Peruvian politicians. So, we wrote what has been scientifically found, what Peruvian researchers have found regarding this vaccine, and they also began to write insults such as that the government has paid us, that the mask doesn’t let us breathe, it doesn’t let us think. Obviously, my name was mentioned there too. Many times, with plenty of insults.

Silvia: Melina tells me that members of the groups that she mentions in her report accuse her and Salud con Lupa of having exposed them.

Melina: They claim we have . . . We have looked into their private life, just because we have checked who they were or what they are working on, and because we also call them anti-vaccine when they are not, but rather anti-experiments, that we are spreading lies and that this can be grounds for legal action. Events have also been organized via Zoom, where some lawyers—because these groups also work with lawyers—mention that they may want to know what the legal complaint process is for media that misinforms.

Silvia: What do you think gives these groups legitimacy? I mean, why do people trust them instead of what we report in the media, for example, about how safe vaccines are?

Melina: Yes, I think it is fear. I believe that there is a lot of fear that people have about this new virus, and they play a lot with the fact that the media is bought, the Peruvian media are bought by the government, they want to manipulate you. So ignore them. Pay attention to us, we are a minority, but we will continue, we will continue to give you the truth, something like that. So people, maybe very often, can distrust some media outlets; it is possible, but in that sense, well, they are playing with lives now. So, I think there is mistrust of some media and also of the government in general. I’m talking about Peru; it may also happen in other countries. And the desire to follow someone, or something. One day, for example, on a bus, I overheard a woman saying, “No, I’m not going to get vaccinated. My pastor has told me not to get vaccinated. This is not written in the Bible”. So, it’s also in part that if my group, the place I want to belong to, is telling me this is going to hurt me, why not believe them?

Silvia: We’ll be back shortly.

Daniel Alarcón: Hello, ambulantes. We are closing a great year in which we managed to produce 80 episodes between Radio Ambulante and El Hilo. We are very proud to have introduced you to memorable characters each Tuesday on Radio Ambulante, but also to have been a reliable source of information every Friday at El Hilo. This would not have been possible without the support of those who contribute to our membership program. If you have not donated, but you are motivated by this journalism, and you want to help support our production, please make a donation before December 31. Go to radioambulante.org/donar. Many thanks!

Eliezer: We’re back with El Hilo.

Mónica, in our last segment we talked about the misinformation spread by anti-vaccine groups. As a scientist, what are you doing to spread information about the pandemic and fight misinformation?

Mónica Feliú Mójer: Well, many things.

Eliezer: This is Mónica Feliú Mójer.

Mónica: I am a scientist by training and a communicator. I’m the communications director for the non-profit organization Ciencia Puerto Rico.

Eliezer: An organization with approximately fifteen thousand students, scientists and teachers committed to science. Together they have organized initiatives to promote education and scientific research in Puerto Rico.

Among many things Mónica does as part of her job, she connects scientists with the media.

Mónica: Another of my important projects is one we have been doing for a year now called Here We Take Care, which is a community impact project to place science at the service of vulnerable and marginalized communities in Puerto Rico.

Eliezer: In practice, part of this project includes sharing tools to evaluate and fight misinformation.

Mónica: We are strengthening the ability of these vulnerable and marginalized communities to cut those chains of disinformation that can be so harmful, particularly in an emergency situation where having access to information that is correct can mean the difference between health and disease or life and death.

Eliezer: That is precisely what I wanted to ask you about. What leads people to share, perhaps accidentally, wrong information about COVID or about vaccines?

Mónica: One thing that is important for us to understand—and I think this is particularly important and difficult for people like me, who are scientists or who have perhaps a scientific approach to information—is that for most people the data is never data, the facts are never enough. Human beings make decisions and evaluate information based on emotions, on beliefs, on political ideologies, on religious moral values, right? So, many times when people share disinformation, they share it because it causes them an emotion. And the reaction when we have an emotion this strong is to want to share it. To want to share that outrage. So the goal of people who create disinformation, or the goal of disinformation in general, is to feed those emotions that make us react impulsively and share it.

People may also share that information because it helps them feel in control. If we look at the pandemic, it has been a time of great uncertainty; there is a lot that we still don’t know. And then, when you see a piece of information that perhaps confirms something you already believe, or something you identify with, then there is that tendency to share it or to use that information to explain something that we no longer understand and this simply makes us feel a little more in control.

Eliezer: Mónica explained that there are two important terms we have to take into account to understand the origin of the false information that circulates on the internet and among our family and friends.

Mónica: There is something called desinformación, which in English is disinformation. And there is something called false information or misleading information, which in English is called misinformation. I’ve seen it translated in some, in some places, as “mis-información.”

Eliezer: Let’s start with misinformation. It’s about that erroneous information that is shared with good intentions.

Mónica: For example: My uncle shares something through the WhatsApp family chat, and he shares it because he thinks that it will help me and my family protect ourselves from COVID-19. Sometimes he doesn’t even know that it’s false information or that it’s erroneous information.

Eliezer: And then there’s disinformation, which is meant to be misleading.

Mónica: That is what the Russian trolls did during the 2016 elections in the United States. There is a poisonous purpose, or there is the intent to gain something, whether political, social, psychological, economic. I think it is very important that we understand that, because understanding that basically allows us to design a plan of attack.

Eliezer: To evaluate the information we have received and decide, based on that, what to do strategically. Mónica recommends that we start by finding out the source of the information.

Mónica: There are tools, for example in Google, where you can write the phrase of the information you read and add “fact check”.

Eliezer: Fact check, that is, data verification.

Mónica: And then Google tells you, it does a fact check. There is a system that tells you, look, this is true or this is doubtful, the information is suspicious.

Eliezer: You also have to be alert to certain phrases and supposed data and quotes from people in authority.

Mónica: We often see vocabulary such as, “things that scientists don’t want you to know.” They are quite sensationalist. Another thing they use is they take data out of context.

Eliezer: According to Mónica, this is to create confusion, exaggerate or cause alarm.

Mónica: Another thing they use is . . . They take advantage of the prestige of someone’s degree, or the prestige of an academic institution, or a scientific or health institution, to create that illusion of truthfulness. Or to simply give it more weight.

Eliezer: As we saw in the previous segment, groups that have the word “Doctors” in their name, or that give talks at universities. Finally, messages or publications that seek to misinform usually leave you with a final message.

Mónica: Many times, at the end of the post they say: “Do not keep this information to yourself, share it.” Basically, what many of these tactics do is exploit how human psychology works.

Eliezer: And that’s why Mónica says that we are all vulnerable to consuming and sharing erroneous information.

Mónica: The truth is that false information propagates many times faster than information that is true, and once false information has basically caught fire and is beginning to spread like wildfire, it’s very difficult to correct it. One of the things that is recommended is to not repeat the misinformation, even to deny it, because that repetition creates familiarity and then the person says, well, but I have heard this in five different places, and if I have heard it so many times, then it must be true. Finally, as we say in Puerto Rico, “Ante la duda saluda”, in other words, if you are not sure that what you are reading or seeing is true, you’d better not share it. I mean, nobody is going to die because they don’t share something . . . You’ve sent them the twentieth meme of the day or the fifty-fifth video of the day, right?

Eliezer: Mónica, society is not only facing disinformation about the pandemic, but about COVID-19 vaccines. Do tactics to fight misinformation change when it comes to vaccines specifically?

Mónica: Yes and no. Fundamentally, the strategies I have mentioned in terms of how to evaluate disinformation, how to evaluate any information, and how to cut those chains of disinformation, are the same. What I think is important, particularly with vaccines, is the urgency of vaccination.

Eliezer: In other words, you have to move quickly to combat misinformation, because the goal is not only to vaccinate everyone, but to do it as soon as possible.

Mónica: The other thing that I think is perhaps a little different—and that I actually think is even a positive thing, is that we can all play an important role in promoting vaccination. I like to talk about how we can all be ambassadors for vaccination. It is much more likely that, if I have a conversation with a family member or loved one, it is much more likely that I can inform you and help you change your mind, than, I don’t know, a government official, an official health worker or a public health worker, right? So those interpersonal relationships are very important.

Eliezer: Mónica says that it is not necessarily about convincing people to get vaccinated, but about giving them the necessary information so that they can change their minds on their own.

Mónica: And when we are doing this—I mean, I understand the frustration, I understand the concern that many people have, especially where vaccines are available. When they hear that someone does not want to be vaccinated, knowing the serious consequences that COVID-19 can bring and how vaccines protect us against it. I can understand because I have felt that frustration, I have felt that anger. But something I always try to do is take a step back and try to understand why. Where does this resistance come from? Because a person who thinks the government is trying to harm them is not the same as a person who thinks that due to their own health issues their condition might worsen if they get vaccinated.

Eliezer: That is, you have to understand the context for each person. Because there are many medical, social, and even historical reasons that lead to their skepticism.

Mónica: There is a history of racism, of abuse, of oppression in science and medicine, right? and we cannot ignore that history. Particularly when it comes to these populations that have historically been unprotected and abused by science. So having that empathy for another person, trying to understand their perspective, their point of view, helps us find a way to answer.

Eliezer: Despite her promoting the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, Mónica also has relatives who do not want to be vaccinated. As perhaps happens to many of you.

Mónica: There is a person very close to me, who is an elderly person, a person who has multiple health conditions, and this person is in Puerto Rico, so they were eligible to be vaccinated since December or January of this year 2021 and they were always finding excuses, you know? “Oh, I have these issues and well, I’m not going to get vaccinated for that reason.” Or, “There are more people getting vaccinated, so we’ll have herd immunity, herd immunity is going to protect me.” Or, “The issue is that next week I have such-and-such a thing going on and so if I get vaccinated, next week the side effects will not let me do that.” And I had multiple conversations with this person about why it was important, answering their questions, trying to calm their fears a bit, and in the end what I ended up doing was sending them a message when the Delta variant started to emerge. And I said, “Listen, from the bottom of my heart, I am concerned, I am very concerned about this variant, the impact it can have. You have these health conditions, which means you are high-risk. And I, I love you and I don’t want to—and I wouldn’t want to think what could happen to you if you get sick. So I strongly ask you to please consider it, please get vaccinated.” Several weeks later the person was vaccinated. And they sent me a photo, and I remember the moment I received the photo. I put down the phone and began to drink my tears of happiness. That’s the kind of thing we can all do. That’s what I mean when I say we can be vaccination ambassadors: with that empathy, with that solidarity, with that affection, we can have these conversations with our loved ones about why it is important to get vaccinated. Because the reality is that vaccination not only protects me as an individual; it protects my community and it protects my people.

Eliezer: Mónica, thank you very much for talking with us and for your work.

Mónica: My pleasure, thanks to you.

Daniel Alarcón: This episode was produced by Inés Rénique. We at El Hilo are Silvia Viñas, Eliezer Budasoff, Daniela Cruzat, Mariana Zúñiga, Denise Márquez, Elías González, Desirée Yépez, Paola Alean, Xochitl Fabián, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, and Carolina Guerrero. Our theme song was composed by Pauchi Sasaki. Part of the music for this episode was composed by Rémy Lozano.

El Hilo is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios and VICE news. Thanks to those who have joined Deambulantes, our membership program. We depend on members like you to guarantee the kind of journalism we do at El Hilo. If this podcast helps you better understand what’s going on in Latin America, consider making a donation today. Regardless of the amount, your contribution will help us ensure that our rigorous and independent journalism goes on. Join us too, at elhilo.audio (slash) apóyanos. Thank you very much!

And to keep up with the most important news in the region and hear how this and other stories we cover are developing, follow us on our social media. On Twitter and on Instagram you will find us as the elhilopodcast.

Well, that’s it. On behalf of everyone at Radio Ambulante and El Hilo, happy new year. We’ll return with a new episode of Radio Ambulante on January 11. Until then, I’m Daniel Alarcón . . . Thanks for listening.