The Importance of Being Ernesto – Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

[Daniel Alarcón, host]: Hello, Ambulantes. Last week we told you about El Hilo, the podcast we’re about to release. We’re very excited. We know that you have been waiting for a new podcast from us, and it’s almost here.

We also know that understanding all the news that comes out of our region is difficult. There is a lack of context, analysis and history… That’s why we created El Hilo.

Every Friday, El Hilo will dive into breaking news, like the plebiscite on a new constitution in Chile, or the presidential elections in the United States; but also stories that get lost in the headlines, like the effects of the climate crisis in the Andes, or the working conditions of food delivery riders.

Visit elhilo.audio/correo to subscribe to our newsletter and keep up with the latest of this new podcast.

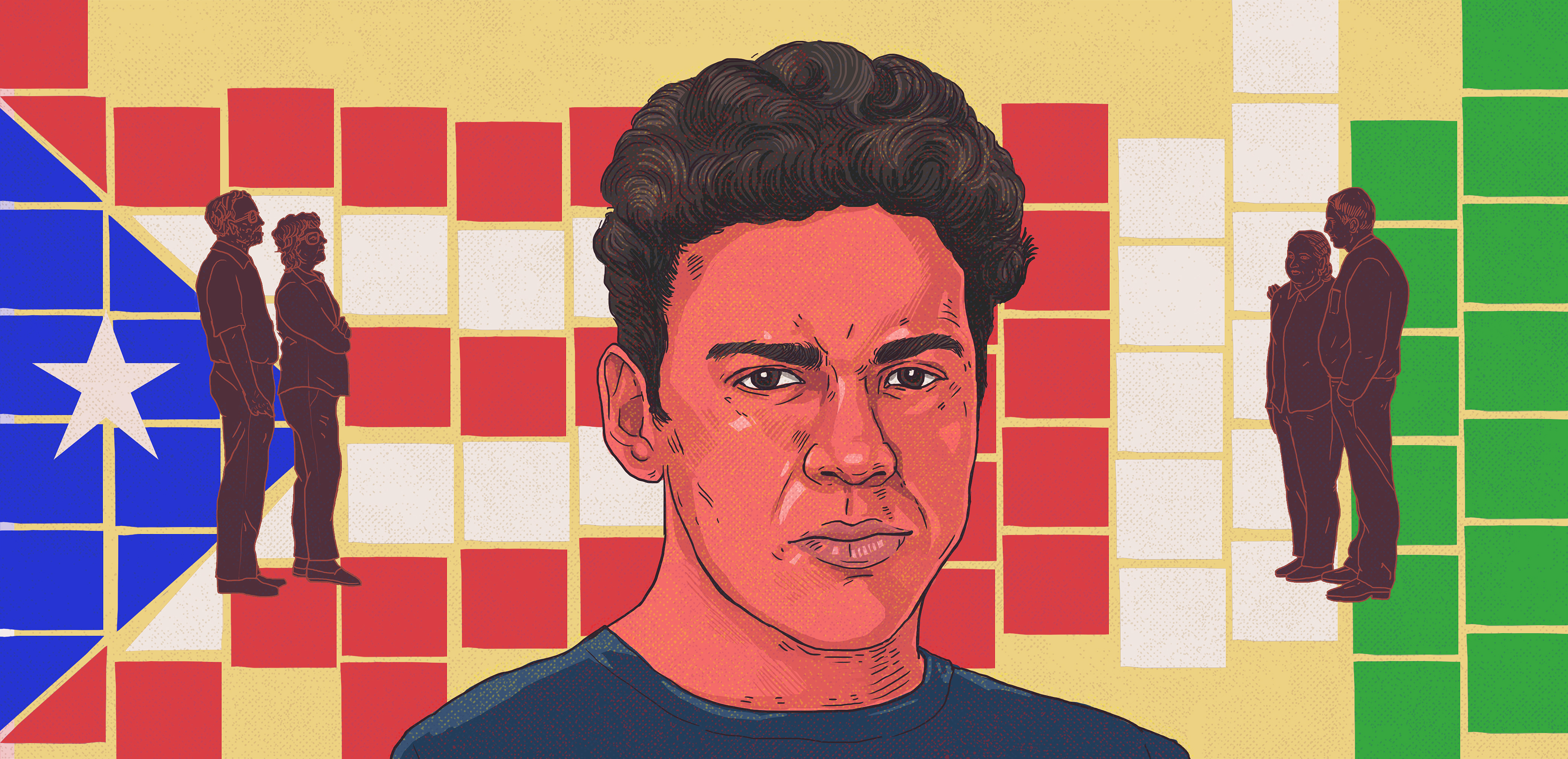

Welcome to Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Today we go back to our archives, with a story first published in 2015. A story about identity.

What’s in a name? It’s… well, a question that you’ve most likely heard many times before, and maybe you were named in honor of your grandfather or your grandmother. In Ernesto Gómez’s case…

[Ernesto Gómez]: Well, they… they named me Ernesto because of Che, you know, and as a symbol of solidarity… among Latin American countries, right?

[Daniel]: And this says a lot about the environment Ernesto grew up in.

[Alma]: For us, Ernesto Che Guevara is…

[Gabino]: The most important symbol…

[Alma]: …A very important symbol. So we decided to name him Ernesto because… This child was a reflection of this proletarian internationalism.

[Daniel]: That is Alma and Gabino, Ernesto’s parents. Together, they are Mexican activists. And the name they gave their son has a much more complex story, with a radical past that Ernesto would spend the rest of his life trying to understand.

From San Juan, Puerto Rico, Luis Trelles tells the story.

[Luis Trelles, producer]: Ernesto had a typical childhood for a Mexican kid growing up in the ’80s. He grew up in the city of Chihuahua in the northern part of the country. He played baseball, skipped school with his siblings… typical stuff. Until one day when Ernesto was ten years old, his parents took him to the office of a psychiatrist that was a friend of the family.

[Ernesto]: The way I remember, it was… was on the second floor, a dimly lit office. The three of us sat on a long sofa.

[Luis]: And the psychiatrist proceeded to ask Ernesto questions, boring questions even.

[Ernesto]: How’s everything? How’s school? How’s baseball?

[Luis]: Ernesto didn’t know why he was there. Until the psychiatrist looked at his parents and told them.

[Ernesto]: And well, the reason you came… you have to tell Ernesto why he’s here, right?

[Luis]: So, Alma and Gabino Told him the truth.

[Alma]: That there were children of the womb, and children of the heart.

[Ernesto]: But they were both loved the same. And that I was a child of the… of the heart, right?

[Alma]: That he had another father and another mother.

[Luis]: That explained some things. His skin color, for example, was a little darker than his brothers’.

[Ernesto]: And I remember that they hugged me and kissed me. My mom had always been very affectionate, right? But my father was always more distant. He didn’t usually give hugs, like he was rough, you know? And I have this memory that’s one of the warmest memories I have of them both, you know, being between my parents while they’re hugging me and giving me kisses, right?

[Luis]: But after they had left the appointment, Ernesto tried to erase everything from his head. He wanted to get back to his own life, as if nothing had changed.

[Ernesto]: It terrified me to think that my brothers were going to reject me, you know, that during some kind of game or fight they bring that up, right? “Ah, no you be quiet, you’re adopted stupid ‘negro’.”

I never externalized this feeling. I never said anything in front of my parents, you know? And never to my brothers. This is something that I think I’ve never… said to… to anyone, right? It was the fear of… being rejected by my own family, right?

[Luis]: But Alma and Gabino had to tell him the truth for reasons that will become more obvious in a little bit. So, one day they decided to take Ernesto for a drive. They wanted to talk with him alone.

[Ernesto]: The memory I have… have of this moment is like a camera in slow-motion, right? It’s like going in the car, my parents were in front, I was sitting in the back, in the… the middle. And as if they were in sync, right? my parents… turned to look at me. And from there I knew, you know? so– something’s coming, right?

[Alma]: And we told him, “Well, you haven’t asked us anything.”

[Ernesto]: “You don’t want to know anything? You don’t want to know who your parents are?” And I remember, I mean, my attitude was, “No… I don’t want to know, and I don’t care.”

[Luis]: But Ernesto didn’t say no, he kept quiet. Alma and Gabino talked to him about a man that had lived with the family a few years back. Ernesto recalled the man and remembered him as “Mone.”

[Ernesto]: Look, as a kid, there was a time when this guy Mone, lived with us. He had… no hands, I remember that clearly. And his face was sort of disfigured. And he used to play firefighters with me in the backyard.

[Luis]: When Ernesto turned 4, the man without hands and with a face filled with scars, disappeared from his life. And now, Alma and Gabino were telling him that Mone was his father.

[Ernesto]: And I remember that the t– two of them looked very serious and then told me: Well, Ernesto, this is something nobody can ever know about. Mone was a ‘guerrilla’ fighter… who fought for Puerto Rican independence, and the gringos were looking for him to put him in jail. And he was hiding away by living us for a while. And then he left.

[Luis]: Ernesto had heard of Puerto Rico before, but if you had put a map in front of him, he wouldn’t have been able to find it.

[Ernesto]: What I knew about Puerto Rico, I think was very… very little, that it was a colony of the United States and that there had been a movement… to liberate it, you know? Maybe I imagined it that way, you know, that it was this submissive island of unhappy people under the control of… the American troops, right?

[Luis]: It was a romantic vision of the island. During that time, Puerto Rico had spent nine decades being a US territory. And throughout that time, different groups had tried to free the island through armed struggle.

Ernesto’s biological father had been part of one of these groups. And his biological mother as well. Alma and Gabino showed him photos of her in prison and told him…

[Ernesto]: This is Dylcia, she’s your mother. She’s fighting for the independence of her country, but they captured her, and put her in jail, and because of that, you’re with us, you know.

[Luis]: Dylcia Pagán was serving a 55-year prison term in San Francisco, in the United States.

Ernesto was only 10 years old and didn’t understand anything.

[Ernesto]: I remember feeling out… out of it. Like being in limbo and saying. “Wow, you know, so, what’s going t– t– to… to… happen to me, you know, now.” And after that, immediately after that they asked me, “Would you like to meet them?”

[Luis]: That was the question. And although he was still confused, One thing was clear to Ernesto. Meet them?

[Ernesto]: For what? I had my parents. I had a happy life. Why meet them? right? But I knew it was something that I couldn’t say no to.

[Luis]: There’s no way to tell a kid these kinds of things without it being… complicated… But Alma and Gabino didn’t have any other option. Ernesto’s biological mother was asking to see him. And they had to tell him the whole truth before taking him to meet her.

[Luis]: So, in December of 1989, when Ernesto was just about to turn 11 years old, he went with his entire family to San Francisco to meet Dylcia.

And to understand why Dylcia was in federal prison, you have to understand that in the ’70s she was part of the Armed Forces of National Liberation, better known as the FALN.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: A group of independence supporters accused of stealing cars, making explosives belong to the Armed Forces of National Liberation, FALN, a secret organization…

[Luis]: The FALN was a clandestine organization that dedicated itself to placing bombs inside public buildings in Chicago and New York. They did this as a way of demanding Puerto Rican independence. The group was founded in 1973, and its members were the children of Puerto Rican immigrants to the US, people who had faced poverty and discrimination. They were convinced that if it meant freeing Puerto Rico, the end justified the means.

But in 1980, after having detonated dozens of bombs that caused five accidental deaths, the organization halted operations almost immediately. During an unexpected raid, the police arrested 11 members of the group in Chicago, and Ernesto’s mother was among those arrested.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: They were found guilty on charges of seditious conspiracy, of wanting to overthrow the US government through the use of force. Here in this federal prison is where they will serve between 35 and 97 years in jail.

[Luis]: Ernesto was not even 2 years old when they arrested Dylcia. And to this day, he’s not 100 percent sure how he arrived in Mexico. But he does know one thing: The FALN members that were still around protected him.

[Ernesto]: And I know that they were hiding me in various parts of the US, until I finally ended up in… in Chihuahua, Mexico.

[Luis]: In Chihuahua, Alma and Gabino belonged to a political organization with ties to the FALN.

[Gabino]: They spoke with the leadership of our organization for… support. And that’s how he ended up… with us. We had recently gotten married and didn’t have any children yet.

[Luis]: Ernesto was born with a different name in New York, but Alma and Gabino gave him a completely different identity in Chihuahua.

Dylcia became a political prisoner, sentenced for seditious conspiracy against the U.S. In 1989, she had already served eight years and was desperate to see the child she had left behind in the hands of the FALN.

The moment he landed in San Francisco, Ernesto was in a constant state of alert. Since he was little, they had told him the United States was the enemy, and now that he was there, he imagined the worst.

[Ernesto]: I was afraid that the United States was going to take me prisoner. And it was something I was afraid of for a long time, that the U.S. government was going to take me away… and not let me go back to Mexico.

[Luis]: In order to get into the prison, Ernesto posed as a cousin-in-law of Dylcia’s. He had to go without Alma and Gabino because they weren’t on the visitor list. Some friends of Dylcia that were on the list went with him. Ernesto remembers that when they entered the visitors’ area they found themselves in a big, cold room.

[Ernesto]: And from there, they called the… the prisoner through the loudspeaker.

88971-024, that was Dylcia’s number.

[Luis]: A few minutes later, Dylcia entered the visitors’ area… and she remembers the exact moment when she saw her son again. This is Dylcia…

[Dylcia Pagán]: When I came in I saw that face, and I said “Wow that’s my baby.” He looked at me, we looked at each other, I took him by the hand– it was like when a… a child is born.

[Ernesto]: She held me and… and… and… and squeezed me… and hugged me and it was the kind of tears that come from deep inside of you, you know? And she touched me and looked at my ears. She lifted my shirt to see my back and my stomach. And I remember that I didn’t feel bad that she was looking me over. Or rather… it was like this gen– genuine kind of affection that a mother has for her child, you know. And… and… and the thrill of meeting her, right? And… and being together.

[Luis]: All of the tension he had felt beforehand about meeting had evaporated in this moment. The similarities between the two were evident. They had the same big eyes, the same skin tone.

[Ernesto]: The memory I have and what I can remember is feeling good about myself, right? It was… like some kind of joy, it was like this feeling this kind of connection, and… and more so in terms of physical appearance, you know? To see someone that I looked like.

[Daniel]: The visit finished soon after and Ernesto said goodbye with a promise —he would be back soon.

We’ll be right back.

[Pop Culture Happy Hour]: There’s so much more to watch and read these days than time available. That’s why there’s Pop Culture Happy Hour from NPR. Twice a week we sort through the nonsense, share reactions, and give you the lowdown on what’s worth your precious time. Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour every Wednesday and Thursday.

[Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me]: So you’re listening to this NPR podcast because you want to be informed. You want to learn something, right? But what if you need a small break? Then you want to check out Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me, the NPR News quiz. It’s the show that lets your lizard brain have fun for once. You can be serious again later. Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me from NPR. Listen to it every Friday.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, we were listening how, being just 10 years old, Ernesto found out that he had another name, different parents, another identity. An identity tightly linked with the Puerto Rican independence movement. Soon after, Ernesto traveled from Chihuahua to San Francisco to visit his biological mother in jail, a strange encounter, for sure, but one that gave him happiness. At last —physically— he could see himself in someone else.

Luis has the rest of the story.

[Luis]: The following summer, Ernesto went on another trip. This time it was to Cuba with his entire family, because that’s where Mone, his biological father was. Mone was a political refugee, a special guest of Fidel Catros’s administration.

[Ernesto]: I saw him, ran, and hugged him, excited. I was happy to… to see him.

[Luis]: When Ernesto went to see him in Cuba, Mone still had the scars from the bomb that exploded on him a decade earlier.

[Ernesto]: I remember being in his arms, kind of nestled in, and he said to me, “I’m Mone.” And I said , “yeah, I know… I know that you’re Mone.” And I re– remember th– that it was a… a moment where I felt… felt really safe and special.

[William Morales]: It was after almost 10 years of not seeing him. He had officially met me as his father.

[Luis]: Mone’s real name is William Morales. During the ’70s, he was the bomb maker for the FALN… until 1978, when he had an accident while making a bomb in an apartment in New York.

[William]: The… the dev– device exploded and… I lost part of both hands, part of my face was disfigured, and I was caught, and I was put in jail.

[Luis]: In 1980, a few weeks after his sentencing, something unexpected happened. The guards at the prison hospital where William was being kept were doing a prisoner count, and when they got to William’s bed.

[Ernesto]: They pull the sheets and see that underneath there are a bunch of pillows. And that there’s a window open and there are bandages hanging from the window, right?

[Luis]: William escaped, and although he didn’t want to talk to me about the details of his escape, his son had heard the stories and told me William was able to escape from the seventh floor. He had escaped without his hands, using a rope made out of bandages.

[Ernesto]: And he disappeared off the face of the earth. He automatically became the FBI’s most wanted man.

[Luis]: William was in hiding for a long time. There was an extensive network of leftist organizations on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border that helped him. That’s how he ended up at Alma and Gabino’s house, where his son was as well.

After spending some time in Chihuahua, William continued his journey through Mexico with a group of ‘Zapatistas.’ Eventually, he did some time in a Mexican prison, and after that Cuba offered him political asylum. And that’s how he got to the island. It’s like something out of a movie. A life that had taken him from the son he had known by a different name.

[William]: He’s registered under the name Guillermo Sebastián Morales, right? His U.S. birth certificate and all that. You can’t take that away.

[Luis]: That’s why there was a little bit of confusion when Ernesto stayed with William in Havana.

[Ernesto]: The first morning I woke up he said, “Guillermo, Guillermo.” And I was like… I remember that he was calling me and that he went and called me, “Guillermo” and said “Ernesto,” and then I reacted. “Ah, why do you ignore me if you’re Guillermo!”

[Luis]: For the first time, Ernesto realized that he had two totally different names. And that each name had its own past and its own history. And that he, at that moment, didn’t want to be known as Guillermo.

[Ernesto]: In theory, on paper, but I was never Guillermo, right? And that was like, my… my first blow concerning the question of identity, you know?

[Luis]: Ernesto returned to Chihuahua exhausted. The time he spent in Cuba had left him physically and emotionally drained. In less that a year, he had met his biological parents: two strangers that forced him to question everything he had known about himself.

Ernesto was about to turn 12, and from that moment on, his life was split in two. The four adults that decided his future made an agreement: Ernesto would spend the school year in Chihuahua, like he usually did, and then he would go to San Francisco to visit Dylcia for Christmas, and during summers he would travel to Cuba to see William.

That was the yearly routine that Ernesto repeated until he was 15, and throughout this time he tried to get close to Dylcia.

Because the truth was that, for Ernesto, loving Dylcia felt like an obligation.

[Ernesto]: Emotionally, I didn’t feel this connection that she was my mother. But it felt like the right thing to do since she was my real mother, you know?

[Luis]: What d… did you want to love her like a mother?

[Ernesto]: Ah, damn, Luis, because, well, I don’t know. Because she was my mom and she was this hero who had… sacrificed for… Puerto Rico independence, you know? And I had to learn to… to accept that and sympathize with it, right?

[Luis]: And Alma and Gabino also wanted their son to feel it. At one point, they told him it would be good if he lived in San Francisco for a while so that he could spend more time with Dylcia.

[Alma]: I told him, “I prefer to hear you complaining that I pressured you a little to go see your mom than to hear you complain because we didn’t allow you to get to know her and be with her.”

[Luis]: And after three years of constantly traveling to San Francisco, Ernesto started to play with the idea of staying over there.

[Ernesto]: There was also a… a question of living in the United States, in the first world. Of me leaving Chihuahua. It was a little like the American dream you see in movies, you know, of being in high school and playing football, and you’re dating the cheerleaders, and, ah, parties… this teenage fantasy of being the cool kid in school and everything.

[Luis]: So, when he was 15 years old, Ernesto moved to San Francisco with a friend of Dylcia, But the move wasn’t that simple.

Ernesto was about to change his identity completely. Let’s remember that he was born in New York with the name of Guillermo Morales. Now in San Francisco, the adults in his life suggested that he reclaim that identity.

[Ernesto]: And I got my passport as Guillermo and enrolled in school, in high school as… as Guillermo Morales. So I stopped being Ernesto so that I could become Guillermo.

[Luis]: His date of birth, his nationality, even his name, everything changed at the same time. But these changes only happened in San Francisco.

[Alma]: And for us in Mexico, he’s never stopped being Ernesto.

[Luis]: So, in the middle of his teen years, when almost everyone is trying to define themselves. Ernesto started to have two identities.

In San Francisco, the friend that he was living with spoke to him about his Puerto Rican roots.

[Ernesto]: And she put a lot of emphasis on the idea that I wasn’t really Mexican, that I was Puerto Rican and that I had to learn about Puerto Rico to love it and feel it.

[Luis]: And at school, he also felt the need to present himself with this new identity.

[Ernesto]: I felt really disconnected, I didn’t…. really make friends over there. I w– was Guillermo, I was the Puerto Rican.

I remember one time that… that the teacher asked me to speak about my Puerto Rican homeland. What was I going to say about Puerto Rico if I had never been to Puerto Rico, right?

[Luis]: But Ernesto returned to Chihuahua once a year, and there he went back to being himself. The tension between his two identities was inevitable, nevertheless. One example: one time he went to visit his Mexican aunt and instead of speaking about Alma and Gabino like they were his parents, like usual, Ernesto referred to them by their first names.

[Ernesto]: And my aunt said, “No… no… no… no… no wait a minute, ‘cabrón’. What do you mean Alma and Gabino? They are your parents.” And they’re always going to be your parents.

[Luis]: But in San Francisco, Ernesto felt that he couldn’t talk like this in front of Dylcia.

[Ernesto]: With Dylcia, I wasn’t allowed to refer to my parents as my parents. You could see in her face the vein that popped ou– out in anger you know? When I spoke about my parents, I referred to them as Alma and Gabino.

[Luis]: When I spoke to Dylcia about this, I asked her if she ever forbade Ernesto to refer to Alma and Gabino as his parents… and she told me no, never.

But… either way, for Ernesto, it was a huge conflict when it came to his loyalty. And in that moment, he had chosen to be Guillermo, the son of a very important political prisoner.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist]: With cries of liberty and that a united people will never be defeated, protesters marched through the streets of Washington demanding freedom for 15 Puerto Rican political prisoners.

[Luis]: In this clip, Ernesto is 19 years old and has been living in Puerto Rico for a year.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Ernesto]: That… that they are political prisoners and that’s enough… 18 years. 18 years is more than enough.

[Luis]: He had moved to the island to be part of a campaign that sought to free Dylcia and the rest of her people from federal prison.

[Ernesto]: It was a role that I played for a long time, right? And it was how I became the… poster child of the political prisoners.

(DOCUMENTARY SOUNDBITE)

[Presenter]: He is Guillermo Morales. And Guillermo Morales is the son of Dylcia Pagán…

[Luis]: The public TV in the U.S. even broadcasted a documentary about his life.

(DOCUMENTARY SOUNDBITE)

[Ernesto]: My mom was on the run when I was seven months old and I had to wait 10 years to be able, ah… to visit my mother.

[Luis]: His story was both moving and effective. People cried when they heard him speak, and more importantly, some of them donated money for the campaign to have the prisoners released. Ernesto began a series of media tours that took him throughout the U.S. and the Caribbean.

And he started getting more involved in the campaign to have his mother released. But, in private, things were not going well between him and Dylcia. In fact, they barely spoke. Ernesto didn’t like how his mother inserted herself into his life, and even more importantly, he questioned the decision that she made when he was just a baby…

[Ernesto]: You’re growing up, right? And… and that’s fine, but you… you decided to get involved in this because that’s what you wanted to do, you didn’t think about me…

[Luis]: He felt resentment towards Dylcia and the movement. They had recruited him to tell the story of an abandoned child but nobody wanted to know about his happy childhood in Chihuahua.

Ernesto realized what he was feeling in the most unexpected of places: They had invited him to speak at the White House and he went along with four other children of Puerto Rican political prisoners…

[Ernesto]: And, I mean, what they went through after losing their parents: Being victims of bullying in school. Being spat on, having rocks thrown at them, having to move to a different neighborhood because they were being harassed. And then I… I didn’t do it. I remember when it was m– my turn to talk and I didn’t want to talk.

[Luis]: For the first time, he clearly saw the consequences of everything that FALN members of that generation had done, above all else to the generation that came after them.

[Ernesto]: For me, it was a moment to say, “This stuff about ‘oh the revolution’ isn’t so great,” right? And so… There are a number of victims and the victims… most affected are the children of all these people, right? And… and from there, I think I started to change a little.

[Luis]: From that moment on, Ernesto distanced himself from the movement. And he started to travel to Chihuahua more frequently to be closer to his Mexican family.

[Ernesto]: In my darkest moments, there i– is always a light there, it’s the nest. It’s the foundation of who I am… you know.

[Luis]: Meanwhile, the movement to free the political prisoners from jail came to a climax. It was 1999, Ernesto was 20 years old, and President Clinton was in the last year of his administration. In Puerto Rico, the leaders of the movement thought that the decisive moment had arrived to get a presidential pardon… and they got it.

(DOCUMENTARY SOUNDBITE)

[President Clinton]: They have served very long sentences, uh, for offenses that did not involve bodily harm to other people.

[Voices]: Dylcia, Dylcia, Dylcia.

[Luis]: Eleven of the 13 political prisoners decided to accept the conditions offered to them by the Department of justice to reclaim their freedom, and Dylcia was one of them.

Although they were not speaking to each other at the time, Dylcia asked Ernesto to be there when she left the prison… Although he was hesitant, he decided that it was better to be there with Dylcia.

[Ernesto]: It was like a roller coaster, right? Going to the prison that, well, for 10 years I had visited. And I realized how many hours I… I had visited, I think I spent like 23 days in the prison.

[Luis]: Ernesto didn’t know what to expect when he finally saw Dylcia walking out. And when she finally did come out with the other prisoners…

[Ernesto]: The other prisoners yelled, “Free at last,” and they were clapping. “Woo, free at last! Free at last! Free at last.” It was… was powerful, very powerful.

[Luis]: Ernesto was reunited with his mother, and at that same moment found out that she wanted him to return to Puerto Rico with her.

Hundreds of people welcomed them to the island. Dylcia wanted Ernesto to stay with her for a few months, to enjoy her freedom together with her son, but Ernesto wanted to go back to Mexico as soon as possible.

[Ernesto]: And from there we started fighting again, right? About… who I was and about who… she wanted me to be, right?

[Dylcia]: I think that he thought I was going to completely devote my life to him. And I couldn’t. Because I needed to meet people, to go to new places, to see Puerto Rico.

[Luis]: Ernesto was 20 years old and looking for an identity.

His mother, in turn, was a political prisoner that had suddenly turned into a public figure. The tension between the two was inevitable.

The situation between the two of them exploded one day when Dylcia wanted to take him to meet some relatives.

[Ernesto]: And I told her, “No, I don’t want to go there.” “Ah, but why not if they’re your family?” And there I said to her, “No, they’re not my family”. “Ah I’m your mother, and I’m telling you that you have to do it.” And I remember that I told her, “No, you’re not my mother.” And I remember she said to me, “Fuck you, you mother fucker, you son of a bitch.”

And I remember that I was shaking, shaking for the first time… I remember that I looked at her shaking, and I told her… t– I said, you know, “Fuck you, fuck you, fuck you Dylcia, fuck you.” And I left that damn pink house.

[Luis]: I asked Dylcia a few times about this incident, and the truth was that she never told me anything very precise about what happened. For Ernesto, nevertheless, this was the last clash with Dylcia as his mother. When he was 24 years old, Ernesto finally chose the name that he felt represented him.

[Ernesto]: Ernesto Gómez, you know? I mean, Ernesto Gómez everywhere I go, and not only in Chihuahua but Ernesto Gómez everywhere. And I started t– to investigate how to legally change one’s name.

[Luis]: But strangely enough, he didn’t go back to Mexico. Ernesto ended up falling in love with and getting married to a Puerto Rican woman, a revolutionary girl with deep roots in Puerto Rico.

When Ernesto told me his story in the beginning of 2015, his second daughter had just been born in Puerto Rico, and Alma and Gabino had been to the island to meet their new granddaughter.

With time, Ernesto also reconciled with William and Dylcia and now they’re part of his life. That is to say, his family is diverse and complicated… or rather, another reflection of what it has meant being Ernesto.

[Daniel]: Luis Trelles is an Editor for Futuro Media. He lives in San Juan, Puerto Rico. This story was edited by Camila Segura, Martina Castro, Silvia Viñas, and I. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri and the music by Rémy Lozano.

We want to thank Gary Weimberg and Luna Productions for letting us use their clips from the documentary “The Double Life of Ernesto Gomez Gomez.” Luis Trelles used the studios of Universidad del Sagrado Corazón in Santurce, Puerto Rico.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Lisette Arévalo, Gabriela Brenes, Jorge Caraballo, Victoria Estrada, Andrea López Cruzado, Miranda Mazariegos, Patrick Moseley, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, and Luis Fernando Vargas. Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast produced by Radio Ambulante Studios and is mixed in the software Hindenburg Pro.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. To listen more, visit our website: radioambulante.org. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thank you for listening.

In the next episode of Radio Ambulante —a social eruption in Nicaragua.

[Protesters]: A free country or death. ‘¡Que se rinda tu madre!’

[Daniel]: And a journalist that became a symbol of the fight against censorship in that country.

[Lucía Pineda]: They try to turn me against the director. Defend yourself, save yourself. But from what am I saving myself? If we were doing our job.

[Daniel]: Her story, next week.