The Lost Colony [Repeat] | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by Patrick Moseley

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcon. Today we go back to our archives, with a story from 2018, about small insects, but with a huge impact on the ecosystem of an island that was trying to avoid collapse.

We present to you, The Lost Colony.

Ok, alright, so, why are we here?

[Luis Trelles, producer]: Well, look. Uh, we’re here to talk about bees. How much do you know about bees, Daniel?

[Daniel]: Bzzzz! You know what I know about bees. When my son sees a bee, or someone talks to him about a bee…there’s uh…the rumor of a bee, he goes running like a crazy.

[Luis]: Terrified.

[Daniel]: Yes. [Laughs]

[Luis]: Wow!

[Daniel]: That’s what I know.

[Luis]:Well, this story is really about bees, but it starts in a tropical field at the University of Puerto Rico’s bee laboratory.

Hello, how are you?

[Man]: They haven’t said hello to each other…

[Luis]: Nice to meet you.

[Tilden Aponte]: Hello, nice to meet you.

[Luis]: And that was where I met Tilden Aponte, the technician in charge of maintaining the beehives.

[Tilden]: The question is have they ever pet you, because well, normally at some point in our childhood we get stung by a wasp or a bee.

[Luis]: He asked me if a bee ever…pet me. [Laughs.]

[Daniel]: [Laughs.] That’s what I’m going to tell my son. I’m going to say to him “No, León, it’s just petting you.”

[Luis]: And I tell him…

Well look, I don’t remember having been stung, I mean, I’m sure I have been at some point, but I don’t…have a memory of it.

[Tilden]: Well, alright, we’re going to take good care of you…so they don’t sting you and we don’t have to rush you off somewhere.

[Luis]: “Because if you’re allergic and they sting you, well, we don’t want to have to rush you to the hospital.” And when I start to think: “Wow, what kind of story am I producing this time? [Laughs]

[Daniel]: But…Ok…I…I know with that “moon suit” they can’t sting you…

[Luis]: They can sting you.

[Daniel]: They can?

[Luis]: They can sting you if you don’t put it on correctly and most of all I think Tilden Aporte saw me [laughs] in some distress, putting on specialized gear and handling a microphone, and he assumed I was going to leave something undone and that the bees would get in and sting me.

And so, well: I put on this suit, we’re in Puerto Rico, it’s nearly 90 degrees, and the suit is almost an inch thick…

It’s hot.

[Tilden]: Yes…

[Luis]: Tilden explains…he explains to me that with the suit on, basically…

[Tilden]: When you wear it for more than an hour, you…you can easily get up to 118, 120 degrees.

[Luis]: I was sweating like a pig.

[Tilden]: And obviously the uh…dehydration process begins.

[Luis]: And well, there I am, complaining about the heat when one of the main characters in this story appears, Dr. Tugrul Giray. And well, that’s not a very Puerto Rican name…

[Daniel]: That is what I was going to ask you about…

[Luis]: Uh…he…he’s Turkish. He’s in love with Puerto Rico and a Puerto Rican woman, and he’s a biologist and bee expert. And well he comes out to…to meet me, you know, out where the bee boxes are.

(SOUNDBITE BEE BOXES)

[Luis]: And the incredible thing is this guy is like a bee charmer, Daniel, I mean, literally he comes out in his shirt sleeves, and I say to him, Tugrul!…

You’re coming over here without a suit or anything, you’re a brave man!

[Tugrul Giray]: No, no, the bees aren’t…they’re peaceful.

[Luis]: And he told me the bees he works with— and the bees in Puerto Rico in general — are very peaceful, very docile. And that is exactly why I went to go visit him because…these peaceful, docile Puerto Rican bees could, potentially, be part of the solution to save a large portion of the world’s domesticated bees.

[Daniel]: It sounds very dramatic, you’ll have to convince on this one.

Our producer Luis Trelles will try to do just that: convince us that the bees of Puerto Rico have special abilities, abilities that could have important effects outside of the island.

Luis bring us the story from San Juan…

[Luis]: And well, in order to understand the importance of Puerto Rican bees, you first have to understand where they come from.

Because these bees are the product of a very controversial experiment that started in Brazil in 1956, in a lab in São Paulo belonging to Dr. Warwick Kerr.

Aíxa Ramírez, a doctoral student who works in Tugrul’s lab, explained to me that…

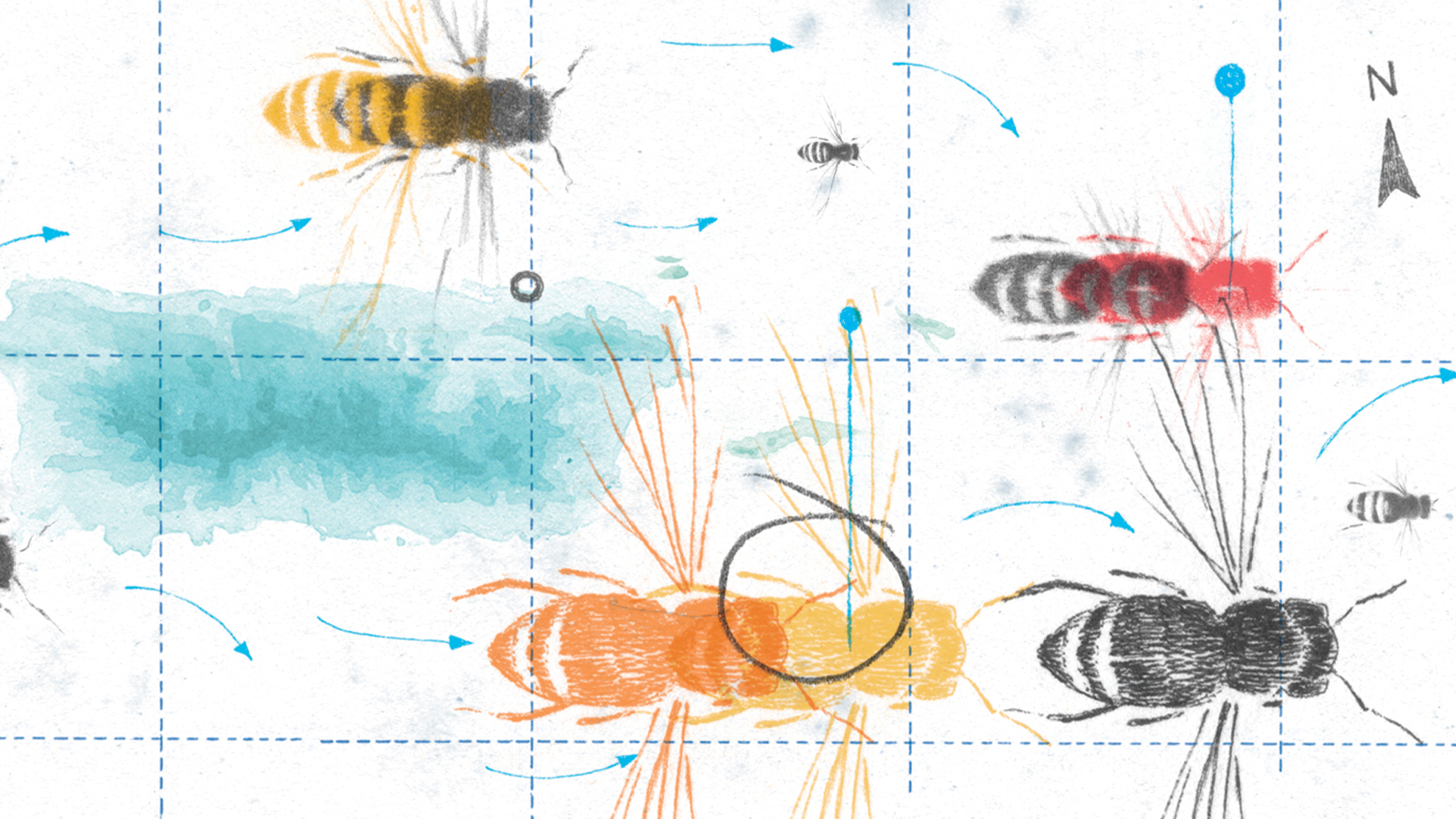

[Aíxa Ramírez]: They wanted to make a cross between the European mellifera and the mellifera bee that comes from Africa.

[Luis]: The mellifera bees are the ones that produce honey. The European mellifera…

[Aíxa]: Is the classic yellow bee with black stripes. It collects pollen and nectar to turn it into honey in its hive.

[Luis]: And that bee had come to America with the arrival of the Europeans. And of course, they quickly spread across the whole continent. Beekeepers love working with them because they’re very productive when it comes to making honey. And they practically don’t sting. They make excellent domesticated bees.

But the European bee does better in some places rather than in others, because the topics aren’t really a good fit for this European bee.

The African honey bee, the mellifera scutellata, does do well in warmer climates. Essentially, these bees are the warmer cousins of the European honey bee, without that snobbish attitude about temperate climates that the northern bees have.

And that’s why Dr. Kerr and his team…

[Aíxa]: Tried to make a cross between them, combining the best of both worlds.

[Luis]: In other words, breed an African queen with drones: male European bees. And in order to do it, Dr. Kerr traveled to South Africa, Angola and Tanzania.

[Tugrul]: So he brought back these bees, a few queens…

[Luis]: Because the queens are the ones that reproduce to make bee colonies. A single queen can have up to 50,000 offspring.

Tugrul explained to me that Warwik Kerr didn’t bring a lot of bees back to Brazil.

[Tugrul]: Fewer than 30.

[Luis]: But that still seemed like a strange way to work to me. I don’t know anything about biology or science but it doesn’t seem like a great idea to move specimens from one continent to another. Especially if you don’t know the consequences that could have.

That’s why I asked Aíxa Ramírez if this was the most appropriate process for carrying out this kind of experiment.

[Aíxa]: His project wasn’t, uh…very well organized when it came to the permits they needed. And historically some people consider him a savior of apiculture and others say that he was the…the…the one who ended apiculture.

[Luis]: And Dr. Kerr continues to be a very controversial figure. Precisely because he started breeding queen bees that he had brought from Africa with European bees, with the abiding goal of creating a bee that could produce more honey in warmer climates. Be before he could perfect the blend…

[Aíxa]: Apparently, the hybrid escaped before the final product was ready.

[Luis]: Dr. Kerr himself mentioned in an interview before his death that the queens escaped due to “handling errors”. But it’s not clear what it was that caused those errors. Aíxa told me that there are several theories.

[Aíxa]: Some say that the doctor, uh, voluntarily —consciously—, opened the…the box the queen was in and she escaped. Some say that it was a technician who was upset with him…with the doctor and opened up the hive to let the experiments out. We really don’t know what happened.

[Luis]: And you have to remember that the queens are the ones who reproduce. And that was exactly what they did: the African queens escaped and reproduced non-stop.

And since they had a totally different genetic make-up, they created a new species.

[Tugrul]: And the Africanized bee was born.

[Luis]: Not African, but Africanized: a mix between the European and African bee. But there was one problem. The Africanized bees had inherited a trait that was very characteristic of the queens Dr. Kerr brought from Africa.

[Aíxa]: Yes, they’re basically more irritable, they’re more anxious.

[Luis]: Aggression. These bees have a very significant predisposition to defend their colony.

[Tugrul]: They can decide that there’s a threat from 20 meters away.

[Luis]: In Africa that threat is usually an animal called the honey badger. It’s the size of a cat and it has been described as the most aggressive mammal in the world. It’s the African bee’s greatest enemy because it specializes in destroying colonies.

But that kind of animal doesn’t exist in Brazil. The most common threat Africanized bees perceive on this side of the Atlantic is people.

[Tugrul]: And so they face this threat with their stingers.

[Luis]: Hundreds of bees descend upon people to sting them.

[Tugrul]: And their response is explosive.

[Luis]: In other words, hundreds, even thousands of stings. None of them is deadly on its own, but all together…

[Tugrul]: They result in kidney failure…

[Luis]: Because each sting transmits a small amount of toxin that affects body tissues.

[Tugrul]: Which is, uh, fatal.

[Luis]: That’s a horrible way to die…

[Tugrul]: Yes, it sounds… it sounds rather bad. Yes.

[Luis]: They were killer bees. That’s what people started calling them in Brazil. And very soon, they became an international problem because they were spreading —slow but surely— across the continent.

[Tugrul]: It wasn’t long before these bees started moving, uh, at a rate of about 100 km a year.

[Luis]: 100 km a year. It’s not a lot: an hour on the freeeway. But it was an incomparable expansion.

In the 60s they made it to Argentina; in the 70s Venezuela; and by the 80s they crossed the Panama Canal. By in the mid-80s they were reaching the Guatemalan-Mexican border.

And of course, the reputation they’d earned in Brazil was sowing hysteria in every Latin American country they reached.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist 1]: And Africanized bees attacked facilities belonging to the Secretary of Education in Campeche. There are wounded!

[Journalist 2]: A swarm of Africanized bees attacked an 82 year old man…

[Speaker 1]: No, we’re also going to have to leave here running.

[Speaker 2]: Listen, there are killer bees in the middle of San Cristóbal!

[Journalist 3]: More than a thousand crusted over stings on this 84 year old man’s body resulted in his death.

[Luis]: And as they spread across South America, the species was growing. Because the Africanized bee was breeding voraciously with other European bees.

[Aíxa]: Uh, the Africanized bee is dominant. And when the genes mix…the Africanized part is the one that dominates.

[Luis]: It was the power of cross-breeding. By 2006, a National Geographic documentary estimated that there were a million Africanized bees in America. And all of them can trace their genealogy back to those African bees that escaped from Dr. Kerr.

By the 90s they had made it to the southern borders of Texas and California. And well, in the U.S.: Total rejection!

(COMMERCIAL SOUNDBITE)

[Speaker]: Now there’s a threat to our peaceful honey bees. The potential invaders are now in Central America, and are predicted to reach the Texas border by 1989. The newcomers are Africanized bees, sometimes called Killer Bees.

[Luis]: And it was in that context of fear —and even panic— that these bees finally made it to Puerto Rico, an island that—I should say— is very densely populated.

[Tugrul]: And that means that they’re going to be in continuous contact with people.

[Luis]: Tugrul explained that a short while after arriving on the island, they started to register deaths in Puerto Rico too.

[Tugrul]: And at first they were, as in other place, killer bees.

[Luis]: From 1994 to 1997 there were 4 deaths attributed to bees.

[Tugrul]: The last one was a boy who was killed by bees.

[Luis]: And in Puerto Rico, the authorities declared war.

[Hermes Conde]: It was chaos. The office of Emergency Management destroyed more than 2,000 hives.

[Luis]: This is Hermes Conde, a Puerto Rican apiarist, in other words, a person who handles bees. Hermes told me that at the time, every time a hive appeared, you called the police, the firefighters or the Office of Emergency Management and Civil Defense.

[Hermes]: They called Emergency Management, like they do right now, and Emergency Management would come right away and “bam bam,” they would spray them with soap and water and kill them.

[Luis]: The soap and water would suffocate them: that was how they solved the problem.

And even though it seems unbelievable, the government’s plan worked, but not in the way they’d anticipated. By the late-90s, bees in Puerto Rico started to change. They stopped being so aggressive.

[Tugrul]: In our research we’ve found that about 10…that there had been about 10,000 reported attacks in those first years. Right now, that number is around 600.

[Luis]: In other words, attacks are 100 times less frequent. Statistically speaking, that is a radical change and it occurred in fewer than 20 years.

There are several studies that attempt to explain why this happened. The most recent was conducted by the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. It came out last year. And there they developed a new theory: In Puerto Rico we eliminated the most aggressive bees, and set into motion an accelerated evolutionary process that gave rise to a new subspecies: more peaceful, more docile Africanized bees.

Incredible, right? The killer bees became a little less killer.

[Tugrul]: In fact, not just a little, but quite a bit less. They’re similar to the European bee in terms of their aggressiveness.

[Luis]: The Africanized bees from Puerto Rico had become calmer, but they still had some of the attributes of the European bees. They’re very prolific pollinators, for example, and they produce more honey.

But they also had the best traits of the African bees. They do well in tropical heat, but more importantly, they are resistant to the number one enemy of bees worldwide: the mite.

[Tugrul]: Mite.

[Aíxa]: Mite.

[Luis]: What’s a mite.

[Hermes]: There’s just one mite.

[Aíxa]: It’s a kind of pin-sized tick that that attaches…to the torso and sucks…hemolymph from the bee.

[Luis]: Hemolymph, or the internal liquid containing the nutrients it needs to survive. These ticks latch onto bees sucking out this fluid. But in the case of Puerto Rican Africanized honey bees…

[Aíxa]: They can clean the mites off of themselves. They can grab them with their mouths, they grab their heads and pull them out. I mean, they have a gift… And mites are vectors for viruses…

[Luis]: In other words, mites are magnets that attract diseases that threaten European and North American honey bees. In the United States, apiarists lose 33 to 48 percent of their hives every year. That’s hundreds of thousands of dead bees.

[Aíxa]: There has always been reduction as a result of some bees dying. Since 2005 or thereabouts, basically the reduction has been greater and what we’re seeing is a depopulation of bees.

[Luis]: Pesticides, industrial monoculture…all of that has contributed to their disappearance. But almost all experts agree that mites are one the greatest threats facing domesticated bee hives.

[Tugrul]: The problem in the US and other places like Europe is that there are no bees that can stand up against mites.

[Luis]: And that has very severe consequences, because a third of the food eaten by humans needs to be pollinated, and honey bees play a very important role in that process because they help spread pollen to plants to create seeds.

Tugrul explained it to me.

[Tugrul]: Uh, we need honey bees for pollination because we need to produce food for…for a world full of people.

[Luis]: And without these bees acting as pollinators, there’s a large number of fruits and vegetables that would no longer be as readily accessible as they are now: apples, onions, avocados…it’s a very long list. And if these crops disappeared from food stands and grocery stores, there would be a very negative effect on a large portion of the global population.

But it’s not just food. Bee pollination is also integral to the balance of the ecosystem.

Aíxa explained it to me like this:

[Aíxa]: We’re going to put it in the context of, uh, food security, we’re going to put it in the context of…the environment, we’re going to put in the context that if there are no trees on riverbanks, erosion could also be affected. I mean it’s a domino effect in scale.

[Luis]: And these effects are already being felt in the US agriculture industry. Particularly in places like California, where bees are absolutely essential to pollinate almonds. A crop that’s worth more than $7 billion for the state.

They have to bring in bees from other areas during the pollinating season. Bees that are like migrant workers, because in California there are no longer enough bees to do that work.

But in Puerto Rico there’s a bee that could offer a solution.

Trugul told me, for example, that…

[Tugrul]: In a recent report they’ve even said that if the Puerto Rican bees disappear, the world could be lost.

[Luis]: But of course everyday people—people who aren’t scientists— don’t know that.

In the early 2000s, bees on the island had already changed. They had stopped being killers. But people kept calling emergency management agents every time they saw a hive. And of course, these agents kept killing the colonies. Almost out of habit.

[Daniel]: And continuing to kill beehives, well, that has very serious consequences. After the break, a group of amateur environmentalists start a rescue mission to save the island’s bees from extinction.

We’ll be right back.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, our producer Luis Trelles told us the story of some killer bees, bees that turned into a possible solution for the problem of bees disappearing in many parts of the world. But before they could do that, they first had to deal with a much more immediate problem: Surviving the Puerto Rican government’s extermination policy.

Here’s Luis.

[Luis]: And this is where Hermes Conde’s crusade begins. He’s one of the people who set out to save the bees.

[Hermes]: I started in 1978 as…as a police officer in Puerto Rico.

[Luis]: And Hermes has had several professional lives.

[Hermes]: I was a sergeant. I was lieutenant. I was a captain…

[Luis]: Later he was the director of the police’s technical operations unit…

[Hermes]: I was the commander of the SWAT Team…

[Luis]: Or what’s known in English as the SWAT Team…

[Hermes]: And then I was transferred to Texas where I worked in a maximum security prison.

[Luis]: He was a prison guard on death row.

[Hermes]: And I went back to work in a maximum security prison in Puerto Rico.

[Luis]: [Laughing] ¡Wow! Wow, you’ve seen it all!

[Hermes]: Yes, everything, everything.

[Luis]: Obviously I wanted to know how a guy like this ended up being one of the most fervent defenders of bees in Puerto Rico.

And when I asked him, he told me that he and his siblings come from a country family.

His grandma handled hives in the forest. But even more important for young people like Hermes, who were raised in rural villages on the island in the 40s and 50s, were his neighbors. Or rather, his neighbor’s daughters.

[Hermes]: The girls were beautiful, too.

[Luis]: And in order to get to them, he had to impress their dad, who was a beekeeper.

[Hermes]: Because they were beekeepers…from birth, because that’s what their dad did!

[Luis]: And that was a very important incentive to learn about the hives. Hermes wouldn’t be near bees for 50 years. But as a police officer, he saw the emergency management offices first hand in the 90s.

[Hermes]: And the agents…from Emergency Management…started killing bees.

[Luis]: And that really bothered Hermes, because it went against everything he had learned as a child.

[Hermes]: I owe everything I am to agriculture. My mom and dad were bona fide farmers. We lived off of coffee, malagueta peppers, eucalyptus…and I consider it my personal duty to pay that back. How? Keeping them from killing off the bees because without bees there would be no agriculture.

[Luis]: Hermes retired in 2011, and then he decided he was going to open La Escuela de Apicultura del Este, or the Eastern Apiculture Academy.

In Puerto Rico there’re several apiculture academies and the vast majority of them are for people who want to learn to make honey, or farmers who want to pollinate their crops naturally. But Hermes’ academy, and maybe a few others, have a different goal: they really serve to train beekeepers to be rescue workers.

[Hermes]: Because every hive that is saved is a hive that contributes to the environment and… we have the opportunity to reintegrate them to…another area that may not have bees.

[Luis]: How long has the academy been in operation?

[Hermes]: 5 years.

[Luis]: And in those 5 years, how many hives do you think you’ve saved?

[Hermes]: Around 800…800 hives.

[Luis]: And little by little, people’s attitudes toward bee hives in Puerto Rico are changing. Aíxa Ramírez explained to me that…

[Aíxa]: Before we didn’t want them and we killed them. Now we do want them and we defend them.

[Luis]: And this change came about just in time to save the Puerto Rican Africanized bee, the new hybrid bee, the one that Dr. Warwick Kerr had tried to create in his lab in São Paulo.

[Aíxa]: Basically the Puerto Rican bee completed the research that started in Brazil. Where we really got a bee that had the best of both worlds.

[Luis]: Bees finally seemed safe, until in 2017 they had to face a new threat…

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist 1]: Hurricane Maria continues to grow stronger in its devastating path through the Caribbean…

[Journalist 2]: Puerto Rico remains on high alert.

[Journalist 3]: The situation is still in a tense calm throughout the country…

[Journalist 4]: According to the authorities, Hurricane Maria is probably the most dangerous history in the modern Caribbean history.

[Luis]: On September 19th, the day before the hurricane arrived, the whole island came to a halt. All of the experts agreed it was going to be the strongest hurricane in more than 80 years. And it’s path was going to go straight through the island.

Everyone prepared as best they could, securing windows and protecting their homes. Tugrul, on the other hand, prepared like this:

[Tugrul]: On the 19th, at 6:30, my students helped me place the bees inside the building so they wouldn’t get hit by the hurricane.

Tugrul wasn’t at his home. For him, the bees in his lab were more important. That night, when he left the lab, he went straight to the panels on his house to secure them before the hurricane hit.

And what happened next, well, is something that all of us who were in Puerto Rico will never forget…Ever.

(NEWS SOUNDBITE)

[Journalist 1]: A total state of amazement: that’s what Puerto Ricans woke up to after suffering the scourge of Hurricane Maria.

[Journalist 2]: Generalized flooding, uprooted trees and downed electrical poles…

[Journalist 3]: Puerto Rico is in the dark. The entire island is unable to communicate.

[Journalist 4]: It could be months, maybe years, before the island is back to normal.

[Luis]: The island was, obviously, devastated. It took Tugrul three days to get back to his lab. And when he got there…

[Tugrul]: The only thing I… There was nothing green then, it all looked burned.

[Luis]: As if the area around his lab had been hit with a bomb.

When Tugrul went into his lab to check on the bees, he realized he had lost several colonies. Thousands of missing bees. Probably dead.

[Tugrul]: Well several of them abandoned their hives.

[Luis]: Out of hunger?

[Tugrul]: Out of hunger.

[Luis]: Tugrul explained that outside of his lab, in local beekeepers’ hives and wild colonies, the situation was much worse.

[Tugrul]: There were no more flowers or leaves on the trees. There was no source of food left for them…there was nowhere the bees could look for pollen or nectar.

[Luis]: And that’s not all. The bees were also facing predators that they hadn’t before.

[Tugrul]: Even pigeons were eating bees…

[Luis]: And inside the hives, the bees were so hungry, they were cannibalizing themselves.

[Tugrul]: So two or three of them were tearing their own offspring in pieces in order to survive.

[Luis]: According to Tugrul’s calculation, the majority of bees in Puerto Rico disappeared in the first month and a half after the hurricane.

[Tugrul]: I think it’s very likely that we lost 90% of the bees on…on…the island.

[Luis]: And the ones that didn’t die, had lost their colonies. Tugrul estimates that nearly 50% of the hives in Puerto Rico were lost.

[Hermes]: Because they lost their habitat and what they’re looking for is food. Since there were no flowers, there was nothing, well, they were looking in zafacones…

[Luis]: Zafacones, or trash cans…

[Hermes]: And soda bottle that people threw out and frankly they were looking for somewhere to go because they had lost their habitats when so many trees were destroyed, you see?

[Luis]: They were completely displaced.

[Hermes]: They went into trash cans, mailboxes, dog houses, doll houses: that’s where they were going.

[Luis]: When I hear Tugrul and Hermes talk about bees after the hurricane, I can’t help but compare it to what hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans experienced. The ones who could went to the United States. It’s estimated that more than 150 thousand Puerto Ricans left within the first five months after the hurricane.

Those of us who stayed, well, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that we were in a situation not too dissimilar to the bees’. We were also displaced, aimlessly going around in circles to see what had happened at workplaces, standing in endless lines where gas was running out, looking for food at supermarkets that didn’t have electricity.

And of course, like the bees, a lot of people lost their homes. More than 70,000 homes —almost all of them made of wood— lost their roofs after the hurricane.

And here you have to remember something that people often seem to forget: Puerto Rico is a US territory, an American colony. After Hurricane Maria, it was assumed that FEMA, The Federal Emergency Management Agency, would launch a massive roof repair program. But this time, it took a long time for aide to arrive and roofless homes became a refuges for hundreds of lost bee colonies.

[Hermes]: Since the houses don’t have roofs, they stand out and are easy to enter.

[Luis]: Tugrul told me that when colonies are displaced like this…

[Tugrul]: In that process the queen may have died…

[Luis]: And the queen has a fundamental role, because the queen is the one that reproduces; and if the queen dies in a situation like this, in which the rest of the colony doesn’t have enough food to produce another queen…

[Tugrul]: That means that it’s no longer possible to replace that…that hive.

[Luis]: In a way it’s a recipe for extinction.

And it was then, about two months after the hurricane, that Hermes and his guerilla force of rescuers sprang into action. They had to save more hives than ever and they were working against the clock.

[Hermes]: Yeah, we are really busy…and we were are up the pace.

[Luis]: How many missions have you done since Maria?

[Hermes]: 28.

[Luis]: After the hurricane the island filled with rescue workers. Experts in emergency medicine, in connecting large electrical generators because practically the whole island had lost power, mortuary experts who knew how to dispose of bodies in disaster areas. In short, all kinds of experts. But I assure you among them there were no rescuers like Hermes and his ragtag band of volunteers.

About five months after the hurricane, I went to the Easter Apiculture Academy to meet Hermes and his volunteers. I wanted to go with them on a rescue mission.

I found myself in the parking lot with Hermes and José Pacheco, his right hand man on these missions.

[José Pacheco]: Hey man, hello!

[Luis]: Hello, how are you?

[José Pacheco]: Here in the struggle, it’s still early.

[Luis]: When I got there they were scraping out a wooden box. It was about one square meter. They would use this box to transport the hive they were going to rescue that morning…

We got in their truck to go to the site of the mission. It was a typical Puerto Rican country house. It was made out of wood and had been damaged in the hurricane.

They were waiting for more of Hermes’ volunteers there, and he started the rescue by giving the group instructions. While he was doing that, I remembered that Hermes had been a police captain and prison superintendent and he had maintained his old habit of giving orders.

[Hermes]: Were going to open… This is a decorative panel. We’re going to try to open it little by little, the bees here are somewhat violent.

[Luis]: And, even though my last name is Trelles, Hermes introduced me as Freytes… Hermes is like that. It’s too late to correct him.

[Hermes]: We’re going to see what’s in there, alright? We’re going to get suited up…

[Luis]: Each volunteer put on protective suites that covered their faces with black mesh to protect them from bee stings.

Some of them had gloves that were too big, others had suits that were too long. The fabric was warn, you could tell it had been through years of use.

So we went through the woods until we came across a wooden house, and we directed ourselves to a tiny room that had lost its windows. I imagine they were blown away by Maria.

There were five rescuers including Hermes and the space was so small that they almost didn’t fit.

Everyone had a job. José Pacheco, Hermes’ right hand, was in charge of the bee smoker, an old metal cylinder that blows smoke: a technique used by beekeepers to confuse bees.

[Hermes]: The smoker, José. I need the smoker and the…

[José]: Here it is.

[Hermes]: The water…here it is now.

[Luis]: Another volunteer sprayed water on the wall with an atomizer. Another technique: water tends to pacify the hive.

[Hermes]: A little water, because they control themselves, they start cleaning themselves…Right now there are a million bees here.

[Luis]: And then Hermes explained that the hive was in the wall, in the space between two wooden panels. The next step was to open up the wall…by force.

As soon as they uncovered the hole, thousands of bees filled the tiny space of the room. The hive had been exposed. It was as if the wall were alive…

[Hermes]: There are more than 40,000 bees.

[Luis]: Here? There are more than 40 thousand bees here?

[Hermes]: Yeah.

[Luis]: Thousands of tiny creatures, one on top of another, moving like shifting sands in a true swarm that had colonized that little space.

The rescue process was simple: the volunteers scraped out the inside of the wall and then transferred the wax and honey filled pieces of the panel into the wooden box they’d brought.

But it was also dizzying. We were enveloped in a cloud of smoke from the bee smoker with thousands and thousands of bees buzzing all over. The protecting clothing was stifling hot.

And that was when I started to feel nauseous. I wasn’t the only one…

[Yolanda]: Oh, a bee got in my suit…

[Fico]: Where?

[Yolanda]: Inside.

[Hermes]: It’s no big deal. Don’t worry. Don’t think about it. Keep working.

[Luis]: Yolanda, one of the volunteers, wasn’t doing well either.

[Yolanda]: My God. Oh my God, help me please.

[Hermes]: Where is it? Where is it?

[Yolanda]: I don’t know. Don’t worry about me. I’m ok.

[Hermes]: OK, calm down, don’t freak out!

[Luis]: Eventually I calmed down. So did Yoli.

And little by little, the cloud of bees dissipated. They’re programmed to follow the queen. A single insect controls the rest of the colony, and apparently the rescuers had managed to transfer the queen to the box because the bees started to gravitate toward that new hive. It would take them a few days, but eventually the 40,000 bees in the colony would move into that box. Hermes would bring the box with the queen to his academy and put one more rescue on his list.

When it was all over, I spoke to Yoli, the woman who had gotten upset, like me. She told me that she and her husband had joined the group of volunteer because they were looking for a change.

Tell me, what attracted you to this?

[Yolanda]: Oh, well, I’ll tell you, uh…Fico and I, it’s just, as a couple we’re…we were in…in a… a moment of transition in our lives. Uh…and we reinvented ourselves, etc. and we stumbled upon this bee thing.

[Luis]: Yoli told me she had been unemployed briefly before the hurricane. So was her husband Fico. They were looking for something to help them find a new path. A reason, perhaps, not to leave the island.

It was already getting late when I went with Hermes Conde and his assistant, José Pacheco, back to the apiculture academy. The building had been a public school before. Hermes uses two classrooms and the rest of the building is abandoned.

They gave me a tour of the apiary. They had filled the classroom with boxes and boxes like the one they just used for the rescue mission.

That was when I realized that the school still didn’t have power. It was almost five months after the hurricane and they and the bees were still in the dark.

And it wasn’t just in the academy.

Later, Hermes told me that many of the rescuers were facing difficult situations.

[Hermes]: They don’t have homes. Their roofs were blown off. I still don’t have power. There are others who don’t have water, but if we stop…

[Luis]: Saving the bees has become the most important priority.

[Hermes]: If we don’t get to work with the…with the hives that they’re placing…that their putting in people’s roofs it’s worse. And we’ve set our own personal situations aside, and we’ve tried to give the bees a start until they can stabilize, because we need to stabilize the situation with the bees now.

[Luis]: And so I came to understand that it was about the bees, of course, but it was also about more than that. It’s possible that with their rescue missions, Hermes and Yoli and Pacheco are helping to save a species that could save so many bee hives all over the world from collapse. But that’s not why they were doing it. For now, the bees are their way of dealing with a much more intimate collapse…that of their own island.

[Daniel]: Luis Trelles is senior editor at NPR Enterprise Storytelling Unit. He lives in San Juan. This story was edited by Silvia Viñas, Camila Segura and me. The mixing and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri. Emiliano Rodríguez did the fact-checking.

We’d like to thank Arián Ávalos from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Val Dolcini from the Pollinator Partnership, and Miguel Carbonell from the Asociación Apícola de Borikén.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Arguelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Laura Rojas Aponte, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill, Bruno Scelza, David Trujillo, Ana Tuirán, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Learn more about Radio Ambulante and about this story on our website: radioambulante.org. Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.