Journey to the Bottom of the City | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: If you already heard last week’s episode, you’re familiar with El Péndulo, our series about the Latino vote in the U.S., co-produced with Noticias Telemundo. More than 36 million Latinos are eligible to vote this year. No matter what happens this Thursday, the team at El Péndulo will analyze the results in a special episode you won’t want to miss. To listen to us, open a podcast app, like Spotify, search for El Péndulo podcast, and hit play.

Alright, let’s jump into today’s episode.

This is Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

On May 29, 2010, Guatemala City was still covered in volcanic ash that had fallen two days earlier when the Pacaya Volcano, some 40 kilometers away, erupted.

That night of the 29th, the rain wouldn’t stop. The announcement by the weather service confirmed what would later become one of the most devastating natural disasters of the decade in Central America.

[Archive soundbite]

[Journalist]: Tropical Storm Agatha made landfall on the country’s coast at around 3:40 pm on May 29, bringing strong winds and heavy rains…

[Daniel]: In the Ciudad Nueva neighborhood, near the historic center of the capital, Desirée was watching the news at home. It was almost 8 pm.

[Desirée]: Suddenly there was a loud bang. It was like a deep volcanic eruption, as if the earth was cracking. And the power went out.

[Daniel]: The sound was accompanied by a strong tremor throughout the house.

[Desirée]: I felt the sensation like what you feel during tremors or an earthquake. I was convinced it was an earthquake.

[Daniel]: The movement lasted a few seconds. Then, silence.

Her youngest daughter, Melisa, was also in the house. Barefoot, in the dark, Desirée went to get her.

[Desirée]: So we got scared and asked, “What happened, what happened?” And we went to look out from the balcony.

[Daniel]: From the second floor, they couldn’t make out what was happening outside. All they could see were a few silhouettes of people running back and forth, trying to avoid the fallen lamp posts that were still shooting off sparks.

Neither of them was quite sure what had happened. They decided to go out and look for answers.

Outside, everything was dark and only a few flashlights from the neighbors threw light on the street intermittently. Some people were shouting and raising their arms to stop the cars from passing. Others were standing in front of the doors of their houses, bewildered.

[Desirée]: Everyone was shaking, kind of hugging their own bodies. I don’t know whether it was because of the cold or the anxiety of what had happened, because we didn’t know whether it had been a bomb, an accident, or something else.

[Daniel]: Most people were looking at a corner where there used to be a three-story blue house.

[Desirée]: And they started to say, “The house sank, the house sank!” And with another neighbor from across the street, we came closer, but not too close because we were afraid of the electric cables. And when I got closer, there was a moment when I saw a large hole, the space where the house had been, and almost half of the entire corner.

[Daniel]: It looked as if a meteorite had crashed into the ground and created a huge, bottomless crater. It had an almost perfect circumference, more than 21 meters in diameter. And it was over 31 meters deep, like the height of a ten-story building, but downwards. The hole had swallowed half of the street and the blue, three-story house, where a textile factory operated.

No words can do justice to this description, but remember this image: a huge, black hole in the ground. If you go to Google and search for “hole Guatemala,” the first image shows the magnitude of what Desirée and her daughter saw in front of them.

[Desirée]: I felt fear, sadness, and also a lot of sorrow for our own house, because I said, “If… if the earth is going to keep on collapsing, the next two will follow.” And the third was ours.

[Daniel]: But she had another worry. Her eldest daughter, Andrea, had gone out in the afternoon and had not yet returned.

[Desirée]: I had been trying to get in touch with Andrea all afternoon and she wasn’t answering the phone. And then I got really worried because I didn’t know whether Andrea was walking by that hole at the time it happened.

[Daniel]: Melisa watched the scene from a distance, from the door of her house, in the rain and the silence. She wondered what had happened to that factory where they made uniforms, and that she liked to spy on with her grandmother’s binoculars from time to time.

But what she saw from the surface was only part of the story. In reality, that hole would not be the only one. Some time later, Melisa would understand that in the depths of Guatemala City there were cracks that endangered many other areas.

That same Melisa, who was 14 years old at that time, is now a journalist at Radio Ambulante. She will bring us this story after the break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Melisa Rabanales, our digital journalist, picks up the story.

[Melisa Rabanales]: In 2010, I lived with my mother, my sister, and my grandmother in that house, where we had just moved in. That Saturday, hours before the hole appeared and when it was just beginning to rain, my sister Andrea had gone out with her boyfriend. At the age of 21, she divided her time between him, college, and what she liked most: working shifts as a firefighter.

That day, before arriving at the place where she was headed with her boyfriend, her fellow firefighters began to contact her. This is Andrea:

[Andrea]: They write us a message: “Guys, the rivers are overflowing. The firefighters who can, please come help, because we need to go and evacuate the people.”

[Melisa]: The messages had a sense of urgency. The rains had intensified and the city was in chaos. They were asking for reinforcements, especially in the most vulnerable areas: precarious settlements that were in the mountains or near streams.

Since Andrea’s boyfriend was also a firefighter, they didn’t think about it twice. They made a detour and went to the station. By then, tropical storm Agatha had made landfall. Andrea got into the first ambulance that left the place.

[Andrea]: It was such an adrenaline rush that I… forgot, I mean, I didn’t tell anyone. I said, “Oh, it’s okay, I mean, I’ll go back and I’ll tell my mom that we helped and so on.”

[Melisa]: She had no idea that, while she was responding to storm emergencies elsewhere, a massive hole had swallowed up a house in our neighborhood.

By then, other firefighters and police had cordoned off our block and were beginning to gather testimonies. Once again, this is my mom:

[Desirée]: They said they had to find out whether there was someone inside the house that had collapsed, the security guard or someone who was looking after the house or was working there at the time.

[Melisa]: Fortunately, there was no one there. The owner of the factory confirmed this a few minutes later. But there were rumors that some people had seen a man passing by at the exact moment the hole opened up. They weren’t sure whether he had fallen into the hole, but many suspected he had.

The street began to fill up with people. I remember that the army and the media arrived.

We decided to go back to our house. My sister was still nowhere to be seen. But that wasn’t the only thing we had to think about. My grandmother, Lety, had Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. She was in bed most of the time, unable to lift more than her arms. To move her, you had to use a wheelchair.

It was almost 9 o’clock at night when some soldiers and personnel from the National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction, known as CONRED, began to knock on our door insistently. They said that we had to get out of there.

[Desirée]: I told them we couldn’t because, one, I didn’t want to leave my house and my things that had cost me so much. And two, we had nowhere else to go.

[Melisa]: They told her that a shelter had been set up for people evacuated by the storm, and that we could go there. But my mother said that it was very difficult with my grandmother. That was an improvised space; it was not really suitable for her.

The conversation with the authorities began to escalate. They made it clear that there was no room for negotiation. It was an order.

[Desirée]: And they gave us half an hour to take out whatever we could. And we had to leave the house: we were very close to the hole, and the ground could continue to sink and our house could go with it.

[Melisa]: There was nothing we could do; we had to take the option that my mother least wanted: go to my father’s house. They had been divorced for two years, it was awkward, and there was still some tension between them, but she called him anyway. He agreed to take us in and very quickly came to pick us up. The firefighters lowered my grandmother on a stretcher and put her in my father’s car.

I remember little of what happened next, perhaps because of the shock, because at that point it was already clear that the tragedy had touched my family. The scenes come to me like short flashes: the rain that wouldn’t stop, my grandmother sitting in the car, my dogs panting, the lights of the ambulances, the fire trucks, the police cars, the media cameras blinding my eyes.

From there, my father took my grandmother, as well as Sarita, the maid who was with us that night, and me to his house. Then he went back to my mother’s house to wait with her for my sister.

Meanwhile, Andrea was returning to the fire station after attending to the emergencies. It was almost 11:00 pm.

[Andrea]: And when I came back, I saw on my cell phone, if I remember correctly, a lot of calls from my relatives, and I got scared and said, “Damn, what happened? I mean…”

[Melisa]: She went home immediately, and a few meters before arriving, she saw the chaos, the people gathered there, and other colleagues of hers.

[Andrea]: It was my fellow firefighters telling the story: “What happened is that a hole opened up, that a house went down.” And I thought, “My family!” I mean, that’s the first thing you think.

[Melisa]: She ran up to find out what had happened. Since she was wearing a firefighter’s uniform, they let her in without any restrictions. She saw our house intact. That reassured her for a moment… but then she saw the hole. She couldn’t believe it. She got a little closer.

[Andrea]: It was raining heavily. You could see the bottom; it was just mud and some sort of pipes along the edges… I think an electric post fell, so it was kind of split in half… I mean, it was a… it was an apocalyptic scene, Melisa, it was apocalyptic, and it was like the earth split… it was like seeing… it’s just…

And then a lady came up to me and said, “I saw the man fall into the hole! I saw him, I saw him, ma’am, I saw him, he fell into the hole!” And then I was like, “Yeah, yeah, don’t worry, we’re looking for him, don’t worry.”

[Melisa]: She was trying to calm the neighbors. But standing there in front of the crater, Andrea knew that it was highly unlikely that the man had survived.

[Andrea]: I stood on the edge and said, “Nobody gets out of this shit alive, I mean, whoever fell is gone.”

[Melisa]: There didn’t seem to be any of the man’s relatives around; the neighbors didn’t know him. Maybe he didn’t live there, and at that moment no one could identify him.

The firefighters and CONRED staff had ruled out the possibility of going down the hole to rescue him. It was dark, it was raining, and the ground was not safe. Everything could get worse.

Andrea went to the house to look for us. My mother was relieved to see her well and safe. She said they had to leave immediately. Andrea decided to go to the home of her boyfriend and his parents.

After midnight, my parents returned with us. With the two of them, my grandmother, and Sarita, we settled in as best we could into two beds and an armchair.

No one talked much about what had happened. We were tired. That night, everyone processed what they had experienced as best they could. My mother dealt with the stress.

[Desirée]: You get to a new place feeling uncomfortable, tired, and you don’t want to bother anyone. It’s a mix of feelings. It’s like you haven’t realized, like your brain hasn’t fully understood what has happened, and it doesn’t know the magnitude of the event.

[Melisa]: I felt strange, too. Being there, at my dad’s, I thought that suddenly we were all playing family, but united by a natural disaster. I held back my tears. I didn’t want my parents to see me crying.

Once at her in-laws’ house, lying quietly under the sheets, my sister was able to vent.

[Andrea]: I cried for what I had unintentionally made them feel, I cried for my house, I cried because even though I had told the woman, “Don’t worry, people will show up first thing in the morning,” I knew that that man wasn’t going to show up, and anyone else who had fallen in was not going to show up, either. So I cried for everything at once.

[Melisa]: Agatha lasted two more days, and during that time it affected nearly 350,000 people across the country: 193 dead, 92 injured, 110 reported missing; 160,000 people had to evacuate, and over 16,000 homes were damaged.

In the middle of all the horror, we were lucky. But that didn’t make it hurt any less. We worried about the possibility that the hole would swallow our house, too. While the authorities were trying to clarify what was going to happen, and after a few weeks with my dad, we had to move to a much smaller house that belonged to my grandmother and that had been left vacant when she became ill.

There we began to get back to our daily routine, and little by little, life began to go on as if nothing had happened. Or at least, that’s how it seemed.

Weeks went by. But information was scarce and reached us only little by little. My mother learned from a neighbor that in Ciudad Nueva, our neighborhood, a repair committee had been formed by the Municipality and some neighborhood leaders we didn’t know. She was never included in that committee, and no authority contacted her personally.

What we learned was also thanks to the media. News of the storm Agatha and the “hole,” as they called it, began to dominate the headlines. It was even covered in the international media.

[Archive soundbite]

[Journalist 1]: This sinkhole in this interjection in Guatemala City looks like something out of a disaster movie.

[Journalist 2]: Agatha left a huge sinkhole in Guatemala City. The image is shocking.

[Journalist 3]: This hole, as they call it, or huge crater, took a three-story building with it. Damn!

[Melisa]: There were various hypotheses as to why it had occurred so suddenly. It was said that it was due to a tectonic fault, that it was caused by the Pacaya Volcano eruption, or even that it was because of the type of soil.

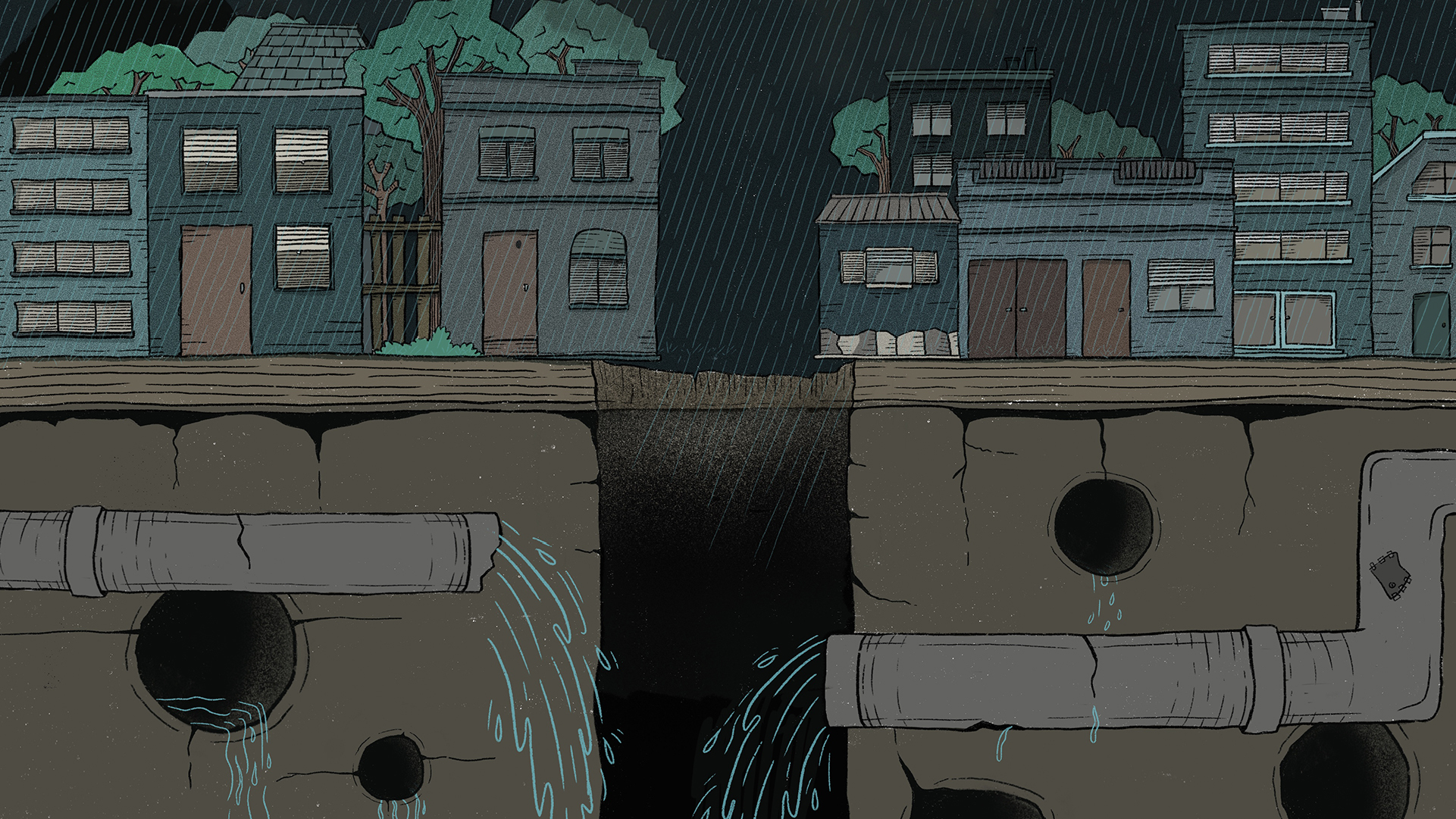

But what all the possible explanations seemed to agree on was that there were faults in the sewage system, particularly in the city’s sewage collectors. These are tunnels that measure between one and three meters in diameter and discharge into basins or rivers of sewage.

According to media investigations, the tunnels had been completed in the late 1970s and Empagua, the municipal water company, had not done any maintenance on them since then. Many of the tunnels had cracks and fissures, which caused the water inside to leak and the soil around them to become soggy. Although most are made of concrete, in the oldest areas they are still made of brick, which is very porous and fragile. It was very likely that the one next to my house was in that state and that this, added to the heavy rains on May 29, caused the land to lose stability and sink.

Despite the published evidence, the Municipality and Empagua remained silent for almost a month, and then they finally flatly denied that it was their fault. They said they had hired some Mexican geologists to examine the place and the geologists attributed the responsibility for the collapse to the clandestine drains of some neighbors.

But that explanation was very weak. And it was not the first time that a hole like that appeared out of the blue. Three years earlier, in the San Antonio neighborhood about two kilometers from our house, a sinkhole had opened up with almost the same characteristics but twice the size. It had left three dead and almost 800 people evacuated.

At that time, there had also been talk of the terrible state of the sewerage system. Several civil engineers and architects assured the media that, since this network of tunnels runs in straight lines, the holes would continue to appear in that same direction. It was only a matter of time.

But no one paid attention and no strategies were planned to avoid it, and three years later, we know what happened.

Days went by and we still had no clarity on what would happen to our house. The National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction, CONRED, sent an expert to assess whether it had been affected. My cousin, who is an engineer, also came and, at my mother’s request, made a superficial inspection. Both confirmed that the house did not seem to have any structural damage, but they could not determine whether the ground was stable. However, three months after the incident, my mother decided that it was time for us to return, even with the sinkhole still there.

And the rumor was beginning to spread that there were thieves breaking into the unoccupied houses, and she was not going to let them take our things. The day we returned, a CONRED official warned her that if we did go back, we did so at our own risk and responsibility.

[Desirée]: And I told him yes, I would take responsibility. I wanted to go back and take care of my things. We never delved too deep into the fears we felt or anything, but we saw it as a fight that had to be fought. We have to go back to our home.

[Melisa]: Other neighbors began to do the same, jumping over the cordoned-off area to enter their homes. We had no other choice; we were not offered a better solution.

For five months, there was no water, and some people collected money tbuy water and fill the wells. When that wasn’t enough, I bathed at the home of a friend who lived a few blocks away. We got used to living like that. I got dengue fever a few weeks later. The doctor related it directly to what had happened because, with the hole exposed and the residual water sitting there, mosquitoes proliferated.

It wasn’t until December of that year, 7 months after the tragedy, that we began to see cement trucks arriving. So the Municipality began filling the hole. They never told us whether that would really prevent the ground from collapsing again, but at least they gave us water, which was our most urgent need at that time. And it was in that same way, without saying much, that we continued with our lives.

[Desirée]: We never sat down to talk, “Hey, what happened? We were close to dying,” because what happened was a very serious thing, and yet we didn’t see it for what it was.

[Melisa]: No one from Empagua or the Municipality approached us to offer us compensation for the damages. But we didn’t ask for it, either. This is my sister Andrea, again:

[Andrea]: Life went on. It’s just that when you experience misfortune, the world doesn’t stop for you. Everything just goes on, everything, everything is the same.

[Melisa]: We lived in that house almost twelve more years. We learned to walk around the hole without fear, ignoring what had happened. We learned that the owner of the textile factory tried to get some kind of compensation from the State, but was unsuccessful and had to relocate his company to another part of the city. The place where it was located is now a parking lot.

My grandmother died, my sister got married, I migrated to another country, and a year ago my mother decided to move to a smaller apartment in a different part of Guatemala City. We have left the incident in the past, and the story became a family anecdote.

But perhaps it is that distance that has helped me see that it is not normal for a huge hole to appear next to your house out of nowhere. It is only now, as an adult, that new questions arise. In the conversation with my sister there is still one question that resonates:

[Andrea]: Should I have done more?

[Melisa]: Done more. Seek reparation, so that someone takes responsibility for what happened to us. And also for that victim of whom we knew nothing.

[Andrea]: Because you and I knew that the man was a real person. I mean, who will hold Empagua accountable and make them apologize? I mean, where is compensation for the family? I mean, how horrible, how horrible.

[Melisa]: We were part of the story of those who were more fortunate, of those who survived and gradually stopped thinking about the hole. But we knew almost nothing about what was happening to the others, and what could still happen. And that’s why I decided to investigate.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Melisa Rabanales continues the story.

[Melisa]: On my last visit to Guatemala, in December 2023, I came across the Ciudad Nueva Únete website. It is a blog by Mapaches de Ciudad Nueva, an ecological collective of young people that was formed in the neighborhood in 2008. The first notes are about festivals, recycling projects, and ecological initiatives. But after the sinkhole appeared, in May 2010, the site began to collect data on this topic, and I became very interested.

I was surprised by the amount of information they had on the subject and how detailed it was. Until recently, I believed that no one had gotten involved in the investigations to clarify what had happened. I had the memory of the committee my mother was told about a few weeks after the tragedy. One that had been formed with neighborhood leaders, representatives of the Municipality, and the National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction.

But back then, that multi-sector table, as it was formally called, had not been much help to us. Actually, it was of no use to us. I don’t know how it was with the neighbors, but no one ever contacted us to gather testimonies or to update us on the process. They didn’t arrange for any kind of repair work, and it simply seemed to us that they had taken the same official position as the Municipality: silence. I tried to contact them several times, but they didn’t respond to any of my messages to schedule an interview.

The fact is that, when I checked the Mapaches website, I understood that it was a kind of dissident, opposition committee. And even so, my family and I didn’t find out about the activities they carried out. We lived next door for more than a decade, and I never saw the commemorative plaque that Mapaches put up there. Nor did I notice the mural they painted on the wall that was left standing and that said, “No more impunity.” Nothing.

I discovered that their website includes a large archive with press articles on the subject, reports of meetings with the Municipality, and photos and articles with their own findings where they demand justice for the victims who had died.

Victims, plural. It wasn’t just one person, as I always believed, but two, and their names were there: Edwin Roberto Velásquez Salazar, 43, and Rigoberto Choc Caal, 23.

The Mapaches Collective ceased to exist in 2012, but I managed to contact one of its members. Her name is Mariajosé España. She is also a journalist, she lived in the neighborhood, and she told me that the first thing they learned about the victims, as we did, was through people who witnessed the incident. But unlike us, the collective was told that there had been two people. This is Mariajosé:

[Mariajosé España]: They were two young men, who were security guards for a private company, and we were told that… apparently, they were on duty. On that corner, which is where the house that collapsed was, there was a telephone booth. So one of them went to the telephone booth to place a call, and that’s when the ground opened up and the two of them fell in.

[Melisa]: The sister of one of them, of Edwin Velásquez, gave the same version to a news program two days after the incident.

Rigoberto Choc Caal’s brother, Isaías, also appeared on another news program. He said he was on the corner opposite him when it all happened. This is a part of that interview:

[Archive soundbite]

[Isaías]: “Come on, man,” he told me. When he said those words, and I turned around to look at him, the house was falling, everything was falling. So I shouted, I called him. I went out to Martín Street, I went out here to that alley to look for him… they couldn’t find him.

[Melisa]: During those days, the authorities said they had gone down the hole twice to look for Rigoberto’s body, but they did not find it. That is why, according to Isaías, they could not give him a death certificate for his brother.

[Isaías]: If the authorities and human rights groups work like this, then I expect to have my brother’s body so they can tell me that what I’m saying is true.

[Melisa]: The Municipality made no statement about Rigoberto’s disappearance. And this continued even when, six days later, firefighters found the body of Edwin, the other victim, in a river about five kilometers from the hole. He had been swept away by the underground current. That same day, his sister identified him and the authorities reported his death, but took no responsibility.

Rigoberto was never mentioned. During its investigation, the Mapaches Collective learned that he was from Izabal, a department in the northeast of the country, and that he had migrated to the city to look for work and help support his younger siblings. At one point, the collective managed to contact the family. This is Maríajosé again:

[Mariajosé]: That was what we learned, but it was a very poor Q’eqchi’ family that did not speak Spanish and had no way of traveling to Guatemala City to identify their family member and file a complaint about his death. So that was also an obstacle that made it hard to follow up and obtain justice.

[Melisa]: Then Maríajosé and her colleagues insisted everywhere that he must be found.

[Mariajosé]: I remember we were still talking with the Forensic Anthropology Foundation. But the political situation was too tense for us to mess with the Municipality, so they would not support the struggle, because it started to become very political.

[Melisa]: Very political because the following year, in 2011, there would be elections, and the mayor, Álvaro Arzú, was seeking re-election for the third consecutive time, and the fourth of an eventual total of five. So it did not seem very convenient for this to become a scandal.

In addition to being an established politician, Arzú came from one of the richest and most powerful families in the country. He had already been mayor in the early 90s and President of the Republic at a crucial moment for the country: the end of the war and the signing of the peace agreements.

So by 2004, when he won the municipal elections again with the conservative Unionist Party, he was a widely recognized figure. According to Maríajosé, Arzú knew how to take advantage of the thousands of municipal employees as a strong electoral muscle.

[Mariajosé]: The thing about the Union Party is that its base is the internal base of the Municipality. They are workers, they are employees who may be coerced or threatened and who have to go out and vote.

[Melisa]: For the Mapaches Collective it was impossible to fight against that power.

[Mariajosé]: So we did have several clashes with the municipal administration. Apparently, we started to become too uncomfortable for them. They saw us as the troublemakers, the ones who were always fighting with… with the Municipality, and it was impossible to talk to them. We had to accept whatever they wanted to do.

[Melisa]: And that did not go much beyond the creation of that committee, which, as we have already said, did not yield results. The Mapaches’ insistence led the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office to publish a resolution in which they asked the authorities to continue the search for Rigoberto, they ruled out the categorization of the sinkhole as a natural disaster, and they demanded that the Municipality and Empagua assume responsibility. It also asked them to take the necessary measures so that it would not happen again. But all that was only written on paper, and no institution did anything.

Two years went by and everything remained the same.

[Mariajosé]: So there came a time when I said, “I don’t want to hear any more about it.” And that’s when I even left the group, because of that, right? Because I was so tired of being very involved in something that in the end didn’t work out.

[Melisa]: And she left the Mapaches Collective shortly before it completely dissolved.

Today, Rigoberto Choc Caal is still missing. I tried to find his family in many ways: with the information stored by Mapaches, on social media, in public records, through neighbors. But I have had no luck.

There is still no death certificate, and in Guatemala there are no public lists of missing people. All I managed to find was the tax record with his date of birth and his identification. There it says that he was removed from the system in 2012 due to inactivity.

After all this time, the only thing that brings me closer to him is a photograph that the same family must have shared with Mapaches and that is posted on the website. In it, Rigoberto looks at the camera. He is wearing a 2006 Italian national soccer team jersey and a gold chain hanging on his chest.

In addition to Mapaches’ research, I also found that a number of academic and institutional reports have been published in recent years about the sinkholes. Most of them agree on what we have already mentioned: the sewer system was not maintained.

But there was something else that I didn’t know until now.

I interviewed one of the geophysicists who worked at CONRED, the National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction, and who was on the committees in charge of repairing the hole in the San Antonio neighborhood in 2007. He confirmed that several official reports were submitted to the authorities at the time, confirming the deterioration of the infrastructure. In addition, they warned that if the issue was not addressed, sinkholes would continue to open. So those warnings were not only from engineers who appeared on the news. There was a formal process of notification to the State.

CONRED asked the Municipality and Empagua for maintenance logs, but, as the geologist told me, not only did they not give them those documents, but they made sure that the reports they had filed were not made public. They said it was “for security reasons.”

After that, Maríajosé told me that several complaints had been filed against the Municipality for its negligence, but none of them got anywhere. No lawsuits were ever filed.

During my visit to Guatemala, I also spoke with journalist Luis Ángel Sas, who has been investigating this problem of the sinkholes since 2022.

[Luis Ángel Sas]: The investigation began about two years ago, when a source informed me that there were problems. There were at least 22 sites at risk of collapse in Guatemala City, I mean specifically Guatemala City, which affected several busy areas.

[Melisa]: I repeat the figure that Luis Ángel was told, so that we are clear on that: 22… yes, 22 sites throughout the city that could collapse at any moment. Luis Ángel had not heard any warnings about this, so he wanted to know more. He began to look for an official statement that would confirm the information, but as had happened to Mapaches ten years earlier, no one was willing to help him.

[Luis Ángel]: The Municipality is like a safe for information. There was a kind of agreement of silence. It was like a lodge of “Nobody says anything.” So it was very difficult.

[Melisa]: But Luis Ángel insisted somewhere else, and that same year he managed to find a former Empagua worker who was willing to tell him what he knew. He was angry with his former employers because they had fired him unfairly, and he had learned that two of his colleagues, due to a lack of company protection, had been swept away by a current of water while working in the sewer tunnels. Both died.

The man, who agreed to speak anonymously for fear of reprisals, told Luis Ángel that he had witnessed the damage to the tunnels for many years, almost two decades. He even saw the damage to the tunnel in Ciudad Nueva, my neighborhood, before the collapse, and it was quite serious.

[Luis Ángel]: And they did do inspections. They raised the alarm, but at first they were forced to keep silent, and those reports disappeared.

[Melisa]: In April 2022, his anonymous source introduced him to Felipe Camey, who also worked in Empagua and who survived the incident that had claimed the lives of his two colleagues.

Camey explained to Luis Ángel that the most critical point of possible collapse was under Roosevelt Avenue, one of the main avenues in the country, where people, thousands of cars and heavy transport go by every day.

He knew this because in April of that year, he had taken photographs and videos while doing a routine inspection of the sewage collector. He had reported it to his superiors, but no one had done anything.

He offered to show them so that they could see the magnitude of the issue for himself. To do this, they would have to go down into one of the manholes, which are spaces under the ground located at different points in the city. From there, the tunnel system can be accessed. That way, Luis Ángel could see the problem with his own eyes and record it on his own. It sounded easy in theory, but it wasn’t.

[Luis Ángel]: We had to do an undercover operation because the Municipality could find out.

[Melisa]: And get them into a huge legal mess. So they designed a plan. Camey would not go down, but two former Empagua workers would, who also wanted to file a complaint and knew the tunnels well. Luis Ángel would meet them at a point on Roosevelt Avenue. It would have to be at night, when there were fewer people and cars passing by. There they would lift a very heavy, round metal cover, hook themselves with a rope to a crane and descend 27 meters down the well.

But the traffic police, EMETRA, patrolled the area constantly, and it would surely seem very suspicious to them that some men were entering the well at that time. So they timed those patrols.

[Luis Ángel]: The EMETRA crew comes by at eight o’clock pm, and then they don’t do another round until nine. So that gives us an hour to arrive, set up, and go down.

[Melisa]: The operation had to be carried out swiftly and with great care. Once everyone had a clear idea, they agreed on a date.

[Luis Ángel]: We went out one night, a Saturday, when it was drizzling. But it was like something out of a movie, as if we were going to rob a bank.

[Melisa]: Luis Ángel arrived a few minutes before eight and parked at a safe distance from the agreed spot. From there, he could see the crane with a pulley on the back. He waited for the signal from one of the men who would go down: a text message telling him he could come near. When he received it, he walked up to meet the rest. They had everything ready.

[Luis Ángel]: It was an interesting adrenaline rush, because you were trying to make sure you didn’t get seen, and if they did ask, what were you going to say? Did you have a municipal permit to do it? They could call the police…

[Melisa]: They put Luis Ángel in a harness and hooked him to the crane with a rope. But before he could get down, one of the men stopped him.

[Luis Ángel]: He said, “No, you’d better not go down. It’s drizzling; we don’t know whether a current is going to come down.” Then he said, “Give me your phone.” I set my iPhone to full resolution and he took my phone and recorded.

[Melisa]: The two workers descended with helmets, gloves, flashlights, and several ropes. Once in the shaft, they walked towards the tunnel and began recording what they saw. This is one of them speaking:

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: The cracks begin here; as you can see, it is damaged.

[Melisa]: There you can see how they shine flashlights on the concrete walls of the tunnel. The cracks are very large.

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: The tunnel is cracked. The whole tunnel is fissured. Soil has piled up.

[Melisa]: The soil falls from above, getting into the cracks. They walk on it, but it shouldn’t be like that. A small stream of waste water should flow through there.

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: The whole tunnel is fissured.

[Melisa]: In another video, you can see that, as they walk, there is more and more soil and the tunnel is getting narrower.

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: Here, the undermining of the tunnel begins.

[Melisa]: They have to crouch down.

They have trouble breathing, and crawl to the place where part of the tunnel has already collapsed. All the earth above has collapsed and formed a mound. They climb over it to see what is above.

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: And here, we enter a cavern.

[Melisa]: Think of three layers. The surface layer, that is, the avenue. The deepest layer, which is the broken tunnel.

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: The entire tunnel is fissured, and here are the leaks.

[Melisa]: And the middle one, where there should have been soil, but now there was a huge cavern.

They could no longer move or stay there for long, so shortly before 9 pm, they went up to the surface with the evidence on Luis Ángel’s cell phone. A month later, in October 2022, he published them in the Plaza Pública media outlet. They also included several reports on the problem of the tunnels. There they managed to determine that the cavern on Roosevelt Avenue was 10 meters long and 8 meters wide, and that its depth from the road where thousands of cars drive by every day was only 15 meters.

Other large newspapers picked up the story, and the conversation continued on the media for a few days. However, Empagua assured the public that that tunnel had been disabled since 2014. Although that did not really reduce the danger, the Director of Sewerage and Sanitation of the company, complying with a summons from Congress, denied under oath that any such damage existed. He said there was no longer anything to worry about.

A month after the report was published, Felipe Camey, who introduced the workers to Luis Ángel, was shot dead outside his home. He never reported any threats and his family declined to comment. In the article that Luis Ángel published reporting his murder, he also revealed that first video that Camey had shot earlier that year, when he discovered the cave and had tried to measure it.

[Archive soundbite]

[Worker]: We have a big hole, Camey! We have a big hole.

[Camey]: Wait for me! Oh my God! Measure the height of this, how high it is. Oh my God, it’s broken here! Measure it there, stand there, stand there, put the tip there. There, there… no, man, here in the center.

[Melisa]: It was clear that Camey knew a lot, perhaps more than the video showed. Here is Luis Ángel again:

[Luis Ángel]: Of course, then doubts arise: What happened? What did he know about the corruption, about the embezzlement of funds? I’m not lying to you, I was scared. Because the first thing you think about, obviously, is about yourself, too. I mean, if something happened to someone who was involved in this, why can’t it happen to me?

[Melisa]: So far, there is nothing to prove a direct connection between Camey’s death and the information he had. Luis Ángel did not receive direct threats for his reports, but he was afraid. After that, and seeing that the investigation into the murder made no progress, he stopped asking Camey’s family and Empagua.

But he did not stop following the issue. When I met with him, he showed me another report that was leaked to him. It had been made by the same Municipality two years earlier, but they did not make it public, either. In it, they identify 17 damaged sewage collectors, although the total number remains unclear.

With that information, in January 2024 I sought out Álvaro Hugo Rodas, current general manager of Empagua, and asked him to explain the risks that exist due to the sewage tunnels and whether they are finally trying to prepare for them. Although Rodas had taken over as director of that institution four months earlier, he is no stranger in the Municipality. He has held several positions there over the last 20 years.

When I wrote to him and his assistant, they asked me to tell them what it would be about. He agreed to the interview, but before starting to record, he made it clear that he would not answer questions about the sinkholes. I didn’t mind.

But before asking him about the report that Luis Ángel showed me on the 17 damaged tunnels, I decided to start with the hole that had opened in 2010 in my neighborhood. This is Rodas:

[Álvaro Hugo Rodas]: I mean, I don’t have any information. I don’t even know what building you’re talking about, but… But I don’t know. No, no, I don’t know when it was formed.

[Melisa]: I insisted.

[Melisa]: Okay, so you couldn’t say exactly what happened in that sinking?

[Álvaro Hugo]: No, no, no, I don’t have… I don’t have the knowledge, or the authority at this time to talk about it.

[Melisa]: Perhaps in his new position as director, Rodas prefers not to speak. But I find it hard to believe that he did not know. In fact, in several press releases about what happened at the time, he made statements about the repair work and what the Municipality was doing. He even appears as one of the representatives on the committee that was formed when the two tragedies occurred, in 2007 and 2010.

Then I mentioned the report of the 17 damaged tunnels that could collapse at any moment.

[Álvaro Hugo]: I don’t know what information you have, or whether you can share it with me. It would help me a lot to corroborate, let’s say, with people, whether these people have already reported it, I already reported it, we already fixed it, or it is pending. So if you help me with that, it would help me.

[Melisa]: I asked him about the victims, not only of the tragedies, but also the deaths of workers that have occurred in recent years while carrying out monitoring tasks in the sewage system.

[Álvaro Hugo]: Again, I tell you, look, it’s as if I were asking you, “What happened? What are you going to do about some worker who was fired from your company two years ago, before you joined?”

[Melisa]: So I asked him about the present, his responsibility since he started this job.

[Álvaro Hugo]: Well, it is not so much that some of them are damaged, but rather that at that time… when they were built, according to our new regulations, they are not as they should have been, and we are… They are being renovated, let’s say, since winter ended, we are working on that.

[Melisa]: After the interview, I sent him the report on the 17 tunnels, as he requested. So far, he has not responded.

Through public information, the Municipality assures that, as of 2022, maintenance has been carried out on seven collector points in the city.

At this point, when we all know that the responsibility for having the craters in front of our eyes is the Municipality’s, and that despite everything nothing changes, it seems like madness. What else has to happen?

Luis Ángel has a metaphor to describe what life is like in Guatemala City:

[Luis Ángel]: The city is on top of a piece of cheese with little holes, and you don’t know when you’re going to walk over one.

[Melisa]: Only these are huge holes. One of them, according to the report that he had shown me, could open up right under the Miguel Ángel Asturias Cultural Center, the National Theater, one of the most emblematic buildings in the country. Its largest room holds two thousand people.

I don’t know whether I will ever fully understand how we can continue living like this, how all this has not been a national scandal. I talked about it with my mom.

[Desirée]: We Guatemalans learn to carry on our own. Perhaps because this country has suffered so much, we are used to the fact that either we do things for ourselves or no one does them for us.

[Melisa]: I also talked about it with Luis Ángel and Mariajosé. We talked about indifference, but that word hurts me, because I’m sure that it is a symptom, but not the cause.

For my sister, it is also a way of surviving.

[Andrea]: It’s really hard. When you are hurt so much as a people, you have to be tough, because otherwise you can’t survive the next day. It’s what happens to us as a people: forgetting is our defense mechanism.

[Melisa]: Because in Guatemala City, there is always something else that can collapse. You go around dodging tragedies: gangs, corruption, hunger, injustice. There is so much going on, on the surface, that we don’t have time to think about what is underneath.

[Daniel]: Over the past 14 years, more than a dozen sinkholes have opened, and not just in Guatemala City. It is estimated that they have left at least ten dead. The cause remains the same: the poor state of the sewage system.

Despite the evidence, the Municipality of Guatemala insists that there are currently no faults that represent any danger.

Melisa Rabanales is a digital journalist for Radio Ambulante. She is Guatemalan and lives in Buenos Aires. This story was edited by David Trujillo, Pablo Argüelles, Camila Segura and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with music by Ana Tuirán.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arevalo, Lucía Auerbach, Adriana Bernal, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Natalia Ramírez, Barbara Sawhill, Elsa Liliana Ulloa, Luis Fernando Vargas and Desirée Yépez.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.