By Request | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Eliezer Budasoff]: At Radio Ambulante Estudios, we are obsessed with great stories. But we know that there are events that cannot be told in just one episode. That’s why CENTRAL, our series channel, is coming soon.

[Archivo Bukele]: People hear populism and say: populism. Does anyone want a populist president?

[Silvia Viñas]: And one of the most relevant stories on the continent is that of the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele.

[Archivo Bukele]: No one. No one? Well, I do.

[Eliezer]: The power of Bukele raises a question for all of Latin America: at what point do the promises of democracy no longer matter?

[Silvia]: From January 17th onwards, listen to Bukele: el señor de Los sueños, a series of six episodes about how an advertiser becomes a politician and convinces a society to give him unlimited power. You can subscribe now by searching for Central on your favorite podcast app… Or visit us at www.centralpodcast.audio.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Before we begin, I want to take a moment to say thank you.

A few days ago, we concluded our most ambitious and critical campaign. We shared with you, our listeners, our situation, and you responded. More than 3,500 people joined our membership program for the first time, joining the 4,000 members who were already supporting us. We couldn’t be more grateful. In the worst year for journalism globally and regionally, the success of this campaign allows us to maintain our independence and editorial ambition, helping us to pursue a sustainable path.

So, let’s celebrate another year of Radio Ambulante and El hilo stories, another year of better understanding of our region, another year of unforgettable voices you won’t hear anywhere else.

On behalf of the entire team, thank you.

This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón and I’m here with Radio Ambulante’s senior producer, Lisette Arévalo. Hello, Lisette.

[Lisette Arévalo]: Hello, Daniel.

[Daniel]: So, Lisette, you’ve brought something you want to show me, right?

[Lisette]: Yes, I want to show you my box of memories, which contains basically the letters that my friends and family wrote to me when I was a teenager. So, for example, I’m going to show you one that caught my attention just now. It has glitter on its cover and beautiful calligraphy with my name that says Lisette and little dots like small sparkles.

[Daniel]: Impeccable calligraphy.

[Lisette]: Impeccable, and I like it so much because it says I am beautiful, I am talented, intelligent, very funny, and above all, a great friend. So this is a great letter to read in times of depression. But I also have a letter from my sister that says, “I love you for being who you are, you are great, not! Ha ha ha ha ha. I love you so much Lippy, happy birthday. Josette”. And I have a two-page, double-sided will, I don’t know whether that’s what you call it, with the words of my cousin José Antonio, who is one year older, and he says, “Dear Li, comma, ugly, etc. Knowing that you’re leaving now makes it very difficult to write to you.” Well, he was saying goodbye to me because I went to Canada for a year to study, and he is telling me, well, very nice things, like that I am the sister he never had, but also not to flirt too much with Canadians. So yes, I have all sorts of letters in this box.

[Daniel]: And do you have any letter that is particularly special?

[Lisette]: Yes, it’s one that’s inside a white envelope which is no longer white due to time, of course, that says, “Niña Lisette Arévalo, presente,” “December 2005.” And when I open it… Well, it’s the typical card that one finds at a gift shop. It has a happy snowman on the cover, holding a broom, and it’s all red and has snowflakes around it. And it is a letter. Which is actually an acrostic that my grandmother Norma wrote for me for Christmas. And of course, it is signed by Pepe and Norma, that is, by both of them, but it’s her handwriting. I mean, here in this letter I see my grandmother, and it is so special because my grandmother has Alzheimer’s, she is 91 years old, and she no longer writes a single word. So I will never see this calligraphy again. She no longer expresses her feelings or what she feels for other people, and obviously she doesn’t pronounce my name any longer. Sometimes she doesn’t even know my name anymore. So it’s extra special for that reason.

[Daniel]: What do you feel when you read that letter?

[Lisette]: Nostalgia. A lot, a lot of nostalgia, and a little frustration for not having spent much time with her. But I feel nostalgic to see her handwriting because her handwriting—my grandmother’s handwriting—was the one on all the birthday or Christmas cards. I don’t know, it makes me very nostalgic for what my grandmother once was, and I want to get her back. Of course, that’s not possible.

[Daniel]: Would you read it?

[Lisette]: Sure. In fact, I also asked her recently to read it.

[Norma]: Your name is like your eyes, just as beautiful. Your noble smile…

[Lisette]: “You are light and you illuminate any path.”

[Norma]: With all our love, Pepe and Norma.

[Lisette]: “December 24, 2005.”

[Daniel]: What do you feel when you hear her reading that letter?

[Lisette]: I mean, it is very likely that my grandmother was not even very aware of what she was reading, but for a second, hearing these words in her own voice makes me see the person she was that Christmas in 2005 when she wrote me this letter. And… and I feel that she is in that handwriting; what she once was is preserved there. And in fact, Daniel, the story I want to tell you today is precisely about this, about letters and their power, and about one person in particular, the Colombian journalist Carolina Calle.

[Carolina Calle]: In fact, when I introduce myself, I say it… that I am neither a whore nor a poet, but I rent myself out to love, that I loosen lumps in the throat, I translate silences, and that, well, I write love letters on request.

[Lisette]: She is someone who understands exactly what we are talking about.

[Daniel]: That story with Lisette, after the break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Here’s Lisette:

[Lisette]: Carolina grew up in Medellín, in the ‘90s, with her parents and her older brother. When she wasn’t riding her bike, she was playing basketball. And when she wasn’t swimming in the pool, she was watching television with her brother. She loved to watch one soap opera in particular, “Cartas de amor.”

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

[Soap opera audio]: I am fed up with this neighborhood. What everyone here needs is someone like you. An expert in matters of the heart, to help all these people with their sentimental problems, which, by the way, are plentiful.

[Lisette]: They wouldn’t miss it for the world.

[Carolina]: He was someone who came to a neighborhood to write love letters on request. Then all the characters in the neighborhood started coming to him, and he tried to solve all those problems and dilemmas. But the character was a poet, and he was very romantic, very inspired…

[Lisette]: So romantic that the main character was called Cupid and he came to the neighborhood handing out red roses to all the women.

Carolina thought it was an entertaining show, and recalling it now, she thinks that all those hours spent watching it contributed to her love of letters. In a time when text messages did not exist, she and her school friends sent each other little notes in class. They greeted one another, asked one other questions, drew pictures, and supported one other in difficult times.

[Carolina]: So one friend wrote me some advice, with another there was some kind of fight, so she wrote asking to me to resolve it and figure out what was happening so that we could talk again.

[Lisette]: It was a way not only to communicate, to express how they were feeling, but to leave a testimony of the present. Carolina kept every letter she received in a special box, thus creating a personal archive of her youth. To this day she has saved the almost 200 that she received in that time. And for her, those letters are a lot more than just pieces of paper.

[Carolina]: Well, I think that every time we write a letter, we make history. I think the letter is an archive. It’s a document. It is the legacy of memory.

[Lisette]: That is the power of letters, the power that seduced Carolina. She wanted to spend her time exploring that world, but writing letters is not a profession. So, despite that inclination, her first instinct when she was about to finish school was to study engineering. Her older brother was already studying engineering, and her father wanted them both to have the same profession. But when she went to college to ask for information, she came across the communications program.

[Carolina]: And I saw literature, history, cinema, radio, and I kind of sensed that I was going to be happy. It seemed very interesting and fun, and that’s when I made up my mind.

[Lisette]: She made the last-minute decision to enroll in a degree program in journalism and social communication. It was 2004, and she was thrilled to start the program. She fell in love with her major when she took a class on narrative and investigative journalism.

[Carolina]: It was like an epiphany where I saw that I could get into journalism to do other things. That I could have time, space to narrate; that I achieved a closeness with my characters that was very, very quick and very beautiful.

[Lisette]: That feeling grew stronger when she was assigned an exercise that she loved: writing a love story. She decided to tell what she was going through at that time with a boy and, as a final presentation, she showed the letters they had exchanged.

Although it was the early 2000s, and text messages had gained popularity, Carolina still preferred to write by hand. She wrote letters to her parents, her friends, her teachers. They were letters of gratitude, admiration, for birthdays or special occasions. Around that time she also began writing letters on request. Carolina was about 21 years old, and the first one she wrote was for a friend who had had a problem with her boyfriend.

[Juliana Puerta]: I was devastated.

[Lisette]: This is Juliana Puerta, Carolina’s school friend.

[Juliana]: Very sad, very confused, without words. I didn’t understanding anything of what had happened.

[Lisette]: Juliana wanted to fix things with her boyfriend, but he didn’t answer her calls or messages. He just would not listen to her.

[Juliana]: I was talking to Caro, and she tells me, “Write him a letter.” And I said, “Caro, I don’t have any words, I mean, first of all I don’t even understand. I don’t even know what to say. I mean, what do I say if I don’t know what happened? I just don’t understand.”

[Lisette]: Juliana was crying when she said that. Carolina answered:

[Carolina]: “Why don’t you come to my house? Since you can’t do it now, if you want, tell me the story and we’ll write him a letter.”

[Lisette]: Juliana agreed. She went to Carolina’s house and told her what had happened: A friend of her boyfriend had taken advantage of her while she was drunk and had kissed her. But her boyfriend didn’t see it that way. He believed Juliana had cheated on him.

Carolina listened attentively and took notes on her computer of everything Juliana told her. They talked for about 2 or 3 hours. After they finished, Juliana went home and Carolina stayed up late writing. The next day, she gave the letter to Juliana, and Juliana began to read it.

In one section, it compared their relationship to a tree; it talked about the time it could take to be cut down and the friend who did it.

[Juliana]: “He was the catalyst for cutting down the tree. If you see him, tell him I say thanks, because never in my life has a friend of the man I love approached me like that and pretended to be my boyfriend. Tell him that I congratulate him, he did very well, the cleverness is evident. Sure, a dark room, a drunk girl—perfect. I’m sure that’s how he calculated things: I get close to her, I kiss her, I caress her, I don’t talk to her, I touch her, I confuse her, I don’t let her touch my face, I simply take advantage of her.”

[Lisette]: The letter continued telling how she had felt, and ended with a good-bye. She told him that she was never able to give him a manilla, a bracelet that she kept for him.

[Juliana]: “This bracelet was for you. After that July 29, I always wanted to give it to you, look into your eyes, smile at you to say, to let you know that you were my desire and to give you my first ’I love you.’ Goodbye, Juliana Puerta.”

[Lisette]: Juliana made a few minor adjustments, and it was done. She thanked Carolina and transcribed it with her own handwriting. She left it immediately with the doorman of her boyfriend’s building, she sent it to him via Messenger and to his personal email address, as well as his email at college. She wanted to make sure he received it by some means, although she didn’t expect a response. She knew he was very proud, and she didn’t think he would ever talk to her again. But he called her the next day.

Using the excuse that she had to pay a fee they had agreed for a trip they had taken to a farm, he took his car and went to see her. He had read her letter, and a door opened for Juliana that she says had been totally shut.

[Juliana]: The letter was a wonderful narrative of everything I had experienced and suffered. Then he, well, with his head a little cooler, was finally able to realize that I had also been somehow victimized by him.

So that is what made it possible for him to listen to me.

[Lisette]: They hugged, and in the following days, they resumed communication. Two weeks later they got together again, and although their relationship ended after a year, Juliana feels that she was able to have proper closure. So much so that they are still friends and she is convinced that the letter Carolina wrote helped achieve this.

It was so important to Juliana that she told her group of friends. This is Carolina:

[Carolina]: “Like I couldn’t, so Carolina helped me and wrote a letter for me…” “Oh, show us the letter.” And then my friends started reading them, and… and after a week or two weeks, I don’t remember exactly, another friend said, “Listen, Caro, I need a letter for Ricardo.” “Hey Caro, I also need a letter for this and that.”

[Lisette]: Gradually, Carolina began to invite her friends to her house, where she lived with her parents. They met in an out-of-the-way room where no one could hear them. Each meeting lasted about an hour and a half, and her friends told her everything while Carolina took careful notes. It was exciting for her.

[Carolina]: It is so nice to sit down with someone, to have that person open up, confide, tell me their story, their memories, and go back in time with me, you know? Even though I am not a part of their memories. So it’s like starting to connect with a person’s past and trying to feel with them.

[Lisette]: It didn’t take long for the story to spread, and strangers also began contacting her and asking to have letters written for them. At first it was mainly women, but later it was the men who reached out to her the most.

[Carolina]: And I began to realize this: that they were the ones who needed this the most. Because, well, the people who were reaching out to me were people who found it very difficult to communicate.

[Lisette]: She met with them in public places. Under a tree. In a coffee shop. In college. She was looking for places where they could spend a long time talking quietly and without interruption.

Carolina set herself to reconstructing the events, asking for descriptions, details that might help her understand the motivations and figure out the emotions. She didn’t charge them anything. She did it as a favor. And what’s more, she says, the experience itself was the most rewarding part.

[Carolina]: Kind of like, “Wow, I helped this person.” Or just that I liked to listen to love stories. We were friends; it was fun; that’s why I did it.

[Lisette]: Carolina continued writing letters until she graduated from college. When she did, in 2009, she began working at the newspaper El Colombiano in the research area and as a feature piece writer. After 3 years there, in February 2012, she decided to quit because she was assigned to cover breaking news and she didn’t like the fast pace. So she became a freelance journalist. And the following year, she answered a call put out by the Ministry of Culture for submissions of digital projects. There was no pay, but they did offer support and feedback. She proposed creating a blog where she would publish letters that she would write on request. And that’s how Letters à la carte got its start.

Carolina started by promoting her services on her Facebook timeline. She posted the following message:

[Carolina]: “If you know what to say but can’t find the words, tell me your story. I can tell you how. I write love letters on request. Letters à la carte.”

[Lisette]: Around that same time, Carolina was participating in a writing workshop with Colombian writer Héctor Abad. When she told him about her blog, he helped her promote it on Twitter. And that brought many more people. They wrote to her from everywhere. From Madrid to Buenos Aires. They asked her for letters for different reasons: to get back in touch with someone…

[María del Carmen Navarro]: “Dear daughter: Although I am writing to you at the last minute, I wanted to send you this letter three years ago. But I didn’t send it because I wasn’t even able to start it. Today, a few minutes before leaving this city, I am drawing strength somehow to speak to you again, even if it is just in writing.”

[Lisette]: To separate from someone…

[Neyla Agudelo Londoño]: “I hope one day you will understand me and know that this decision that now hurts us, makes us uncomfortable, shakes us both, is for the good of the three of us. Believe me, I will never forget how good, how pleasant, how happy it felt to be with you. Believe me”

[Lisette]: To seek reconciliation between a father and a daughter…

[Natalia Ramírez]: “Let’s not put love off for later. I hope there is still life when we want to share it. I hope that time does not turn us into strangers and that it is not too late for you to be my father again, and for me to be your daughter again.”

[Lisette]: The letters were received in different ways. Some got no response. Others did. With the last one we heard, for example, the girl managed to regain contact with her father.

For some, these words may sound trite… cheesy or cliché. For others, perhaps, they are perfect, appropriate, precious.

But one thing is certain: Carolina’s letters help. People who lack the emotional tools or the confidence to express themselves open up. And their lives are better off for it. In fact, one of the most satisfying moments for Carolina was when, after giving a girl a letter she had written, the girl was silent and then said:

[Carolina], “I opened my heart to you. And you were able to listen to it.” And then I was like, “Oh, that’s sweet.” It means I succeeded.

[Lisette]: And that is more than enough.

In a very few cases, Carolina has refused to write a letter on request. When it seemed to her that someone was contacting her because they were too lazy to do it themselves, like congratulating someone on their wedding, for example. Or once when a man who had treated his girlfriend very badly wanted a letter to get her back.

[Carolina]: I couldn’t do it. And I warn people about that, too, because… it’s like, as we talk, I have to feel the love. And I also have to feel that they have a noble purpose.

[Lisette]: She hasn’t run into that kind of requests often. Most people who seek her are in crisis and need someone to listen to them. Someone to help them vent.

Just as in college, Carolina did not charge for writing letters. She sometimes bartered services with people. One letter in exchange for legal advice, another in exchange for the logo design for her blog. Other times, she agreed with people on a token payment.

And when they authorized it, and after some time had passed since she had written the letters, she published them anonymously on her blog. She thought that maybe there were people who were going through similar situations and those words could be useful to someone else. And that’s exactly what happened.

[Carolina]: Letters à la carte became a meeting point. A place where people found each other. They googled “how to write a letter for this,” and they found it. And that letter spoke to them. And so they come back and write to me, “Look, this letter taught me such-and-such, so I want to donate this other letter to you.”

[Lisette]: Carolina kept enriching her blog little by little, with letters written by her, and donated letters that came from different parts of the world.

In 2019, the Secretariat of Social Inclusion, Family, and Human Rights and the Secretariat of Culture of Medellín sought her out to teach a letter-writing workshop at El Pedregal Women’s Prison.

Carolina had worked with that prison system before. During her college internship, she worked on the internal television channel of the Bellavista National Prison. She created a film club with actors, scriptwriters, and camera operators. She did this in addition to writing various stories on the topic. She was always interested in working in prisons and with people deprived of their liberty.

At first, Carolina didn’t really like the idea of doing the workshop because it was only one morning. She wouldn’t be able to devote the time she wanted to each of the women who were there. But after some thought, she decided to go ahead and do it.

[Carolina]: They will get some good out of it, right? I don’t have to be so negative. Not everything in life needs to follow a process. And if I can give them something, even if it is something small, well, I’m going to give it.

[Lisette]: Carolina began planning the workshop, and when the day arrived, she went to the prison feeling very excited. She told the women what she did, and she brought letters so they could do the exercise of opening the correspondence, reading it, and then writing their own. When she introduced herself and explained what they would do, many of them were excited… But something else happened: a group of women was staring at her.

[Carolina]: I saw them with their eyes wide open; they were surprised and began asking, “So you would write my voice?” “So you would write for me and you would send a letter to a relative of mine who is far away?”

[Lisette]: She realized that these were women who could not read or write. They were part of the prison literacy program. Carolina had not planned the workshop with these women in mind. But she adapted quickly and started talking to them, listening to them. She couldn‘t do much in the limited time period.

When she left, she looked up the prison regulations and learned that those women could send and receive an unlimited number of letters. She started thinking about the ones who didn’t know how to read or write…

[Carolina]: So I start to wonder, where do those unsaid words go? Where do those unwritten characters go? If there are no visits. If there are no letters, if all they have is a phone, but in order to use it you have to have an account balance and someone has to make a deposit for you. What if the family doesn’t have a telephone? I mean, there are a lot of possibilities that are not covered in any of the regulations.

[Lisette]: At that moment, something clicked.

[Carolina]: I say, “Well, yes, this is where I’m needed. Right here, because here I am going to fit. Here I can contribute with something.”

[Lisette]: And yes, she would contribute much more than written words for those women.

We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Our senior producer, Lisette Arévalo, continues the story.

[Lisette]: The work that Carolina wanted to do with the women’s group had to wait. The arrival of the pandemic closed the prison doors to all types of visits. From home, Carolina began giving online workshops, virtual narrative journalism classes at college, and, of course, she continued writing letters for others. But throughout that time, she constantly thought about the women she had met and wanted to work with again.

In 2021, a year later, virus restrictions began to be lifted and, little by little, the country started opening up again. Including the prison, although there were still limitations. Only one visitor per family was allowed, and they could not be over 60, or children.

If people in prison are already living in isolation from their loved ones, the pandemic only deepened those distances. Even more so if they couldn’t read or write. Carolina sensed that in that double confinement—physical and mental—the women in prison would have so many accumulated feelings, so much stress to release, so much anguish to share that she wanted to visit them as soon as she could. So she contacted the institutions that had invited her to teach that first workshop and proposed her project. It was approved two months later.

In September 2021, Carolina met in a prison classroom with 15 women who were part of the literacy program. She told them again what Letters à la carte was all about, and explained that the idea was that she could write letters for them. Then she said:

[Carolina]: “Those who voluntarily want to be part of that process, tell me. I will sign you up and then I will have individual meetings with each one of you.”

[Lisette]: 12 of the 15 stood up from their seats.

[Carolina]: And they approached me, and the teacher had to ask them to line up in an orderly manner, and then I wrote down their names. And I was like, “What a beautiful chaos…”

[Lisette]: But what a powerful chaos, too. It seemed to Carolina that that eagerness and disorder only showed how much they needed someone to listen to them. How much they were waiting, without knowing it, for someone to offer them something like that.

[Carolina]: They needed what a letter normally accomplishes. It’s just that, since we have everything within reach, we take it for granted. So what they wanted was to mitigate an absence, shorten distances, talk a little about their confinement, and let out all those words they had kept in for so long.

[Lisette]: For almost two months, Carolina went almost every day. In a small corner, a kind of waiting room at the entrance to the prison school, they placed a plastic table covered with a tablecloth, and a chair. Carolina had only her notebook and her pen to take notes. She did not record any of the conversations.

Carolina told me that many cried, others were happy as they recalled their families, or were silent for a moment.

[Carolina]: I remember one of them, for example. I started asking her questions, and suddenly she stopped answering, and I told her, “If you want, we can stop.” And she had tears in her eyes and she shook her head, “No.” In other words, she didn’t want to end it; she was just waiting a bit so that her words could come out when they were needing to come out. And for that, we needed that silence.

[Lisette]: We managed to talk to one of them: Sol.

[Sol]: I never thought of writing to my family because I hadn’t heard any news from my family for a long time, or seen them.

[Lisette]: Sol is a 31-year-old woman from the coast, with dark eyes and black, wavy hair. She has a small tattoo on her neck, and scars on her arms and face. She had been incarcerated for a little over 2 years when she met Carolina.

She wanted, more than anything, to communicate with her mother, who is now 80 years old. They were always very close. Ever since she was a little girl, Sol accompanied her mother to work selling clothes, and they went together to the Magdalena River, in southwestern Colombia. She missed her a lot. During all the time she had been in jail, her mother had not been able to visit her. She lived very far away and did not have money for the ticket and the stay.

So, when Carolina offered to write letters on request, Sol was thrilled.

[Sol]: And I thought it was all very sweet, very pleasant. Not everybody does that; just a very few people do it, but they are angels that God sends to you.

[Lisette]: They met in the prison on a foggy morning. It was cold, and cumbia music could be heard in the courtyard. Just as she did with the other eleven women, Carolina gave Sol all the time she needed. And she always had something to say:

[Carolina]: And Sol had very vivid memories. So I was able to ask her questions, and she navigated through those memories and… and she talked and talked and talked, and I took notes sometimes and I asked questions and, well, that’s how we put together that letter.

[Lisette]: On that occasion, they spent two and a half hours in which Sol could really open up.

[Sol]: I told her many things that I didn’t tell anyone else, because I felt I could trust her.

[Lisette]: Sol asked her to write down everything she felt about her mother and the memories that accompanied her during the confinement.

[Sol]: The lady helped me write that I missed her a lot, that I loved her a lot, that… I wanted her back despite many things she knows about me. That at one point I felt sad, but I miss being a child and working with her selling clothes, selling cassava, selling matches. I miss her food, the cheese, the arepita, this and that; that I wanted to fight for her, that I didn’t want to leave her all alone, because she is alone.

[Lisette]: Carolina wrote all that down in her notebook. When they were done talking, she went home and the first thing she did was transcribe everything Sol had told her onto the computer. She started writing the letter that same day so as not to miss any details. It was what she did with every woman she talked to.

After two months of work, when she finished all the interviews and her letters, she took them to the jail to edit each one. They generally made small changes. One woman, for example, asked her to say “Dear Mita” instead of “Dear mom,” because that’s what she called her affectionately.

[Carolina]: Or there was a sentence that read, “I feel alone; not even a dog visits me here.” She had told me that in our meetings. When she heard it, she said, “Erase that sentence; it’s too harsh.”

[Lisette]: So she edited the letters one by one until she had the final versions. Then she wrote them out on the computer. But neither Carolina nor the other women liked that part.

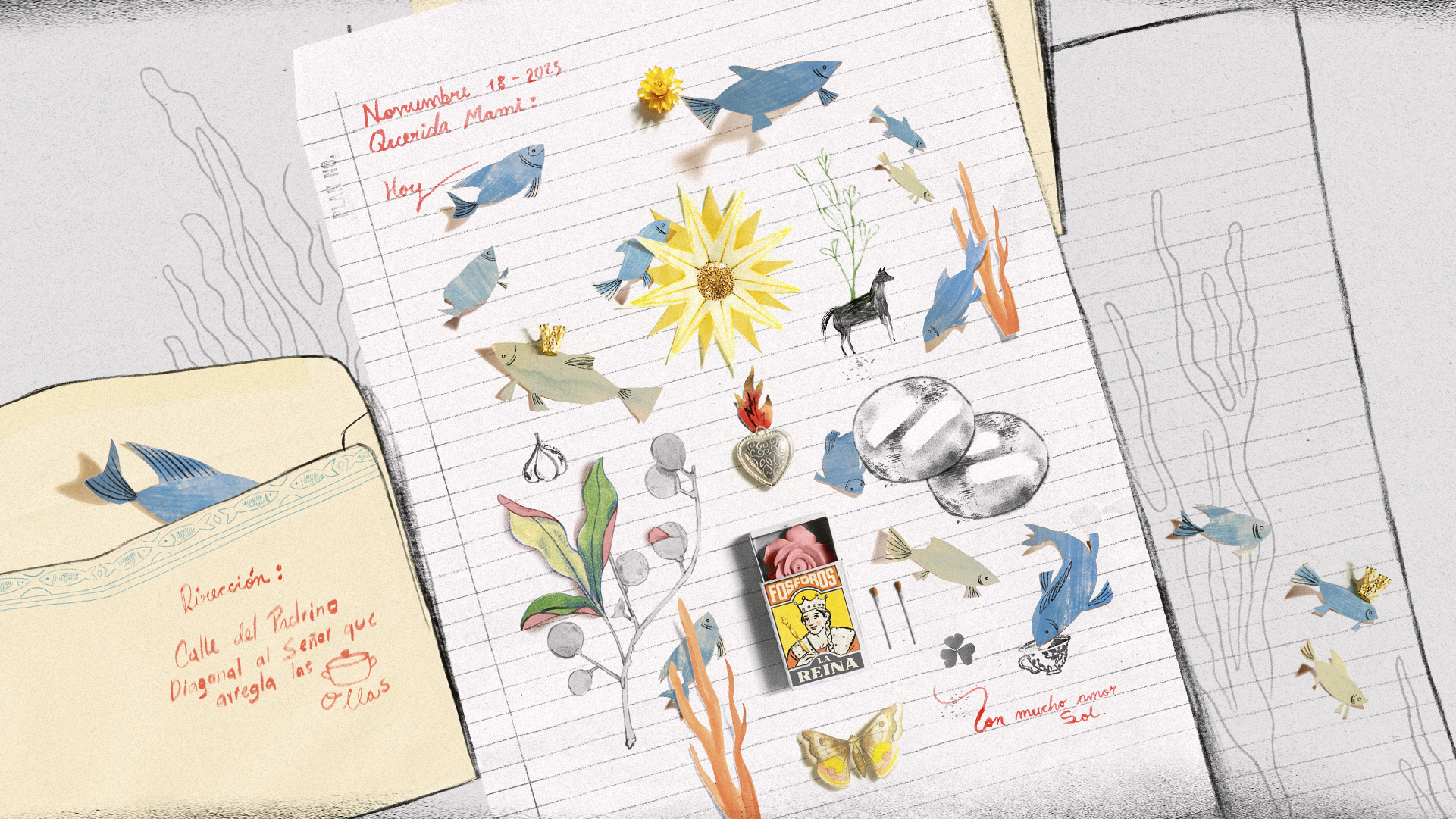

[Carolina]: But of course, there came a moment when they would say, “Oh, come on, can’t you make a little drawing?” So it was also like, “Oh, my gosh, how can we send these letters printed from a computer? How awful! It can’t be that cold, that dull. That is a contradiction”.

[Lisette]: Carolina didn’t want to use her own handwriting to write the letters by hand because she thinks it is pretty shoddy. So, in November 2021, she decided to do something she called a “letter casting” to get people to donate their handwriting and transcribe the letters. She published the call on her social media accounts.

[Carolina]: And it was the most beautiful thing. You have no idea. I mean, a lot of people wrote to me and I sent them the letters… And of course, those are people who love calligraphy, artists, fans of writing. And so they began to transcribe these letters by hand, and moreover, they did the… They added color, small drawings. It was just so beautiful.

[Lisette]: They signed with hearts, used different colored pens or drew stars next to the recipient’s name. There is one in particular that I really like. The entire margin of the page is filled with drawings of all kinds: a Bible, hands, a telephone, a clock, a calendar, a birthday cake and lots of flowers.

Carolina asked the people who wrote the letters to make two copies: one to send to the recipient and another for the women to keep as a souvenir. She also asked an illustrator to draw the women based on the contents of the letter. In the illustration for Sol, for example, she was shown as a girl with a red backpack, holding her mother’s hand, the two of them facing away, toward the river.

A month later, the letters were ready. We asked some friends to read some fragments for this story:

[Nora Cardona]: In the afternoons I go out to school. I have already learned to sign my name. I know how to write my name, but I don’t know how to write the last names; I will soon manage to do it. I know the alphabet by heart now, and I can put some letters together with vowels. I can read some words. This motivates me a lot to be a better person.

[Mariluz Vallejo]: Although it has been almost a year without seeing you, I find you here day and night. When the guard locks the cell door at eight at night, I close my eyes, even though I am not sleepy, and there in the darkness I see you again. At five in the morning, when a metallic sound wakes me up, you three are my first thought.

[María T. Palacio Daza]: Hello, Mita. I have a lot to ask you, to tell you. I haven’t heard from you for a long time. The last time was when we were talking and I heard a noise. I imagine it was because the child dropped the cell phone and it got damaged. Because since that moment I haven’t heard anything at all. Nobody answers me and I don’t receive calls, either. How sad.

[Isabel González]: Here we have a roof, some cement boxes to put our clothes in, a slab to sleep on, and the only thing I carry is the regret of not having listened to you.

[Cecilia González]: I couldn’t be by your side at your wake. I saw you on a screen, surrounded by people with masks. You wore a smile with your eyes closed and seemed to be sleeping. I felt tremendous pain in my body. I always wanted to be part of everything. I regret not having been able to accompany you in the end.

[Lisette]: Carolina obtained a permit to meet with the women in the prison yard. She gave them the letters and illustrations and, full of excitement, they got ready to send them to their relatives.

[Carolina]: For this to have any effect, they have to be delivered, because otherwise it becomes just a sigh, it goes away, it slips away.

[Lisette]: The women gave Carolina addresses and phone numbers so that shecould deliver them personally. One letter was sent through the prison mail service. Other women asked her to send theirs via WhatsApp instead. But there were three who were not clear about the information. One of them was Sol.

[Sol]: I didn’t know how to send the letter to the home address. Because with my mother, getting to her house is very complicated. But I didn’t know the address of the house. She didn’t know. When she says, “Give me the phone number for your family, your mother, so I can call and tell her that I’m going there.”

[Lisette]: Sol gave her the number, and Carolina called her as soon as she left the prison. When Carmen, Sol’s mother, answered, Carolina told her that she had a letter from her daughter and that she wanted to deliver it.

[Carolina]: And the lady said, “And a letter about what, or what?” And I said, “Well, it’s a love letter…” And at first it seemed the mother didn’t believe it. She was like, “Well, that doesn’t exist…”

[Lisette]: Carolina finally persuaded her, and she said that the house where she lives did not have an exact address, but that it was in such-and-such a town and in such-and-such a neighborhood.

[Carolina]: And she also told me, “On Padrino Street, diagonal to the man who fixes pots.” And I was thinking, “Well, if I go to the post office and give these instructions, they will laugh at me.”

[Lisette]: She felt that she had no choice but to go and deliver it personally. But it didn’t happen immediately.

6 months went by until, in early June 2022, Carolina was finally able to travel to the coast to look for Sol’s mother. She was accompanied by a friend.

When she arrived in town, the first thing she did was go to the river, because Sol had many memories of that place. She thought maybe the house was nearby. But when she asked a local woman, she told her that she didn’t know where Padrino Street was. She asked another woman, who said…

[Carolina], “No, that neighborhood is very far away and very dangerous.” So then I was like, “Oh, well”. Then I just got the letter out as if it were a good luck charm or a passport to pass through anything.

[Lisette]: She kept trying. She used an app on her cell phone to enter the name of the neighborhood and followed the instructions. She came to some unpaved streets full of stones. There she asked a man again about Padrino Street, and he said that if they paid him, he could guide them. So they paid. When he took them to that location, he repeated what they had already been told: to be careful because it was very dangerous.

Of course they were scared by that warning. The idea was not to expose themselves to danger in order to deliver the letter. They hesitated, but being so close, Carolina decided to continue. Still with Sol’s letter in hand and already in the neighborhood, the final thing she needed was to find the man who fixed pots. Then a man came out of a house.

[Carolina]: I asked the man, “Listen, I’m looking for the man who fixes pots.” And he asks me, “What’s his name?” And I said, “Oh, no, I don’t know the name of the man with the pots. But I do know the name of a lady who lives close to him. Mrs. Carmen.” And then he said to me, “Oh, the lady who sells second-hand clothes?”

[Lisette]: Carolina had no idea whether that could be Sol’s mother, but she decided to follow that lead. The man gave her some instructions: go straight along a ramp, turn left, then right down an alley… There she asked another woman about Carmen and she told them, “It’s that house.”

[Carolina]: I think I’m blushing because I feel my cheeks hot and my heart is racing. And I start walking, but inside I think, “Oh I hope it is, I hope it is.” And my hands are sweating…

[Lisette]: A man came out of the house, and Carolina asked him whether Mrs. Carmen lived there. He answered that she did, and went to call her.

[Carolina]: And I thought, “Oh, it can’t be, how great!” And then the lady comes out, and she was just as Sol had described her to me: short, thin, with long hair… And I tell her, “Hello, Mrs. Carmen, I’m Carolina and I’m bringing you a letter from Sol.” And the lady was so excited she welcomed me, gave me a kiss and told me to come in.

[Lisette]: Carolina went in. They sat in the living room and opened the letter together. It said:

[Carolina]: “Dear Mom, Sometimes I have memories about water. In the river, but also in the sea. Sweet memories and also salty ones. Together on the ferry, crossing from shore to shore, from town to town, on a motorcycle or a boat, walking and calling out, carrying merchandise and earning a living. We sold shirts, shorts, flip-flops, bras…”

[Lisette]: They read it all while they drank a soda. In the end, Carmen told her that she wanted to answer Sol and send the letter with her. Carmen couldn’t read or write, either. So then and there, Carolina started writing down everything she said. It made her happy to know that she would not return to Medellín empty-handed.

A few days after the trip, Carolina went to the prison to deliver the letter to Sol. She found her on the second floor of the school, in a room.

[Sol]: She told me, “Sol María, I was looking for you,” and as always when I saw her, I hugged her and said, “Carolina, God bless you, I missed you…” She said, “Sol, I brought you something.” I asked her, “What did you bring me, ma’am?”

[Lisette]: Carolina told her everything about the trip to the coast, the search for her mother, that she had delivered the letter they had written to her… And most importantly, that her mother had written back. When she gave it to her, Sol hugged her and thanked her. And Carolina went right ahead and read it to her.

[Carolina]: “Daughter, I love you very much. I am in good health. The town is good now; it has grown a lot. There is quite a bit of commerce. They are fixing the streets. I tell you that the ferry no longer exists as you remember it. They got rid of it.”

[Lisette]: The letter said that it was raining a lot, that the temperature had dropped, and that the river level was high. That she had cows, but she had had to sell them and that her house was under construction.

[Carolina]: “I hope you get out as soon as possible. I’m glad you’re studying and making drawings to get ahead in life. I miss you a lot. I have missed you very much. I would like to see you. I remember you very often. I pray to God that you will come out of this well. Mom.”

[Lisette]: Carolina gave her some pictures she had taken of the family: her mother, her father, her nephew.

[Sol]: And when I saw the pictures, it filled me with joy. I let out my joy, happiness, I cried and I remembered many things about my mother.

I felt pain and I felt happiness. As I tell you again, I felt happiness because my mother had never written a letter to me, not even when I was a child. Never. I hadn’t, either.

[Lisette]: For Carolina, watching Sol’s reaction gave meaning to all the work she had been doing.

As for the other two letters that were also not easy to deliver—because there was no exact address or telephone number—Carolina managed to deliver them to their recipients. One was from a woman to her family, who lived on the outskirts of Medellín, in the countryside. They also gave her a letter in response to send to the prison, and Carolina delivered it with photos that she took of them.

She delivered the other one on the same trip she made to the coast. It was difficult for her to get there, but by asking everywhere, she managed to find the mother of Dina, the woman who sent the letter. The mother, Dilma, also sent an answer. But Carolina was never able to deliver that letter. When she returned to the prison and asked about Dina, they told her that she had been released but no one knew where she was. Not even Dilma. Carolina did everything she could to find her, but at the close of this story, she hadn’t heard from her.

And although not finding her is still a pending issue, meeting the women in the prison has been very important for Carolina.

[Carolina]: I think it has also given a lot of meaning to my life and has taught me to value many things. It has been an… an experience that, paradoxically, continues to teach me other ways of life, of love, of freedom.

[Lisette]: Carolina has tried to stay in touch with the women from the prison, and with their families. Including Sol and her mother. In fact, it was from the mother that she learned that Sol had been transferred to El Buen Pastor Prison in Bogotá in late 2022. She was not able to see or communicate with her again. Until we went to visit her.

In September 2023, my colleague from Radio Ambulante, David Trujillo, went to the prison to interview Sol. When we told Carolina that we were going, she sent us some photos and a letter for us to give to Sol.

Although as soon as Sol saw David, she asked him about Carolina, he left the surprise for the end of the interview. First, he handed her the two pictures.

[Sol]: Oh… So pretty. Beautiful, my dear old mother.

[David]: How do you feel?

[Sol]: Fine, sir, fine. And where is she?

[Lisette]: In the pictures, Carolina and Sol’s mother are in a chalupa, a small boat. Carmen has her hair up and is wearing a black t-shirt and a rose-printed skirt. Carolina is smiling, and Carmen has her head tilted towards Carolina. She looks straight at the camera and has a slight smile.

[David]: And what would you like to say to your mother after seeing these pictures?

[Sol]: That I love her very much. I love her so much. That she is very beautiful. My dear old mother is very… she’s old, let’s not fool ourselves. But I would like to spend time with her, sir.

[Lisette]: Sol couldn’t contain her joy. She almost had a glimpse of hope of meeting her mother again. She asked again how she could talk to Carolina to thank her. Then David told her:

[David]: Carolina sent you a letter, too.

[Sol]: Really?

[David]: I’m going to read it to you. Do you want me to?

[Sol]: Oh, sir… Read it.

[David], “Dear Sol…” this was written yesterday.

[Sol]: Yes.

[David]: I think of you often. With love, with gratitude, with a smile. I heard that you had been transferred to Bogotá.

[Carolina]: “I heard that you had been transferred to Bogotá through your mother. I don’t know whether she told you. I visited her in January. Without knowing, I arrived the day after her birthday with a cake in my hands. You can’t imagine her face, her joy, my surprise. It was a happy coincidence. When I suggested going to the river to celebrate, she said yes immediately. She beamed like a little girl. We sailed the Magdalena. I rode in a chalupa next to her and remembered you together, in the letter. I hope you get your freedom soon. I wish you could see her again. I sense that it will happen soon. Here in Medellín, you have a friend. Do not forget me. This is my number.”

[David]: “We have a lot to talk about. I send you a strong, warm hug and greetings to your mother. Carolina.”

[Sol]: Carolina, thank you very much. God bless you. Eh… I haven’t forgotten you either. I feel happy. Thank you for being with my mom.

[Lisette]: After our visit, Carolina managed to contact Sol. This time we were the ones who helped her get back in touch with someone. We were her mail carriers.

[Daniel]: In late 2022, with the authorization of the women in the prison, Carolina published a book compiling all the letters. It is called “Cartas de puño y reja,” and when she had copies, she returned to the prison to give them to the women who are still imprisoned.

Lisette Arévalo is a journalist and senior producer at Radio Ambulante. She lives in Quito, Ecuador. This story was edited by Camila Segura, Luis Fernando Vargas and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri, with original music by Ana Tuirán.

Thanks to David Trujillo for his help with this episode.

Thanks to María T. Palacio Daza, Natalia Ramírez, Nelya Agudelo Londoño, Isabel González, Nora Cardona, Maryluz Vallejo, María del Carmen Navarro, and Cecilia González for lending us their voices for this episode.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Pablo Argüelles, Adriana Bernal, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.