Emos vs. Punks | Translation

Share:

► Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at lupa.app.

► You can read “Emos vs. Punks” Spanish transcript here.

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes

[Daniel Alarcón]: A word of warning: This episode contains vocabulary typical of Mexico City—including words that some people may find offensive, but very cool.

This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Let’s start on March 15, 2008, in Mexico City, which was called the Federal District at the time . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Reporter]: The appointment was at three p.m. at [a roundabout called the] Glorieta de Insurgentes. Young self-styled emos were gathered to demonstrate and defend their ideology.

[Daniel]: What you are hearing is a report from TV Azteca.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Grupo]: Emos, emos, emos, emos!

[Daniel]: For those who are not aware or need a reminder, a brief review: During the 90s, there was talk of urban tribes, groups of people—especially young people—with similar tastes. One of those tribes was the emos.

Let’s see . . . they were teenagers dressed in dark colors, sometimes pink, striped t-shirts . . . tight pants. Long hair fell down their foreheads covering their eyes . . .

“Emo” comes from “emotion.” Their philosophy, if you can call it a philosophy, was to feel—and feel a lot. An adolescent thing. If I were a little younger, I probably would have identified with them. They expressed a sort of theatrical sadness that was reflected in their aesthetics and especially in their music.

Then, that day at the Glorieta de Insurgentes, they were demonstrating because their nemesis had arrived . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Reporter]: The threat came from groups called punketos, and indeed, they came yelling and screaming.

[Punks]: (unintelligible yelling).

[Daniel]: The punks, or punketos as the reporter calls them, are much better known: anarchy, chains, heavy music, piercings, leather jackets and military boots. And the hairstyles, of course . . . mohawks struggling against gravity.

The thing is, the punks weren’t happy about the emos, for reasons you’ll learn later on. But a group set about organizing a beating online.

They set a time, date and even a slogan for the event: “Be a patriot and kill an emo.” The emos were used to brutal bullying, but that specific day, at the Glorieta de Insurgentes, they did what no one expected: They defended themselves.

And that’s what we’re going to tell you about today, the story of one of the strangest battles that Mexico City has ever experienced: the emos vs. the punks, and the consequences that this confrontation had in the counterculture scene of that country.

The Radio Ambulante team includes a person who clearly recalls everything that happened: our production assistant, Fernanda Guzmán.

She will tell us more after the pause.

[MIDROLL 1]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. This is Fernanda.

[Fernanda Guzmán]: First of all, I want to clarify something. I’m going to talk about injuries and resentment, street fights, unnecessary and even gratuitous hatred. But still—and this will sound strange—many of us who remember that battle hold some affection for it. It was the little guy defending himself against the big guy, the bully. There is always something inspiring about that.

When the emos became a thing in the mid-2000s, I was in high school. It’s been over a decade; it feels like an eternity. Being a teenager then was very different from what it is now.

For example, information didn’t circulate the way it does today. Internet was just beginning to be an everyday thing for teenagers in Mexico. Do you remember the phones from that time? With keys, very poor-quality cameras, some still had antennas that you had to pull out to get a signal . . . And to play music you had to use really obsolete technology, like infrared.

Facebook and Twitter already existed, but they weren’t that popular. What people used was MySpace, Hi5, Metroflog. Before we spoke of things going viral, jokes and gossip were spread through email chains with Comic Sans typography, garish colors, and computer viruses. It was a slower and . . . in many ways, simpler life.

Half of my school was or wanted to be emo, and the other half bullied them. That’s how things were. Simple.

But being emo had its charm. That theatricality, that feeling of emotions without filters, that going against what we are told is the norm . . . In your teenage years, these are things that engage you, that you even need.

Here is a confession: I was not immune to that charm. Although I didn’t want to admit out loud that I was into emo, my hair casually always covered one of my eyes. But sure, to whoever asked me, I replied, “No, I’m not emo, no way.” I tried to talk it over once with my dad. “What if I were emo, what would you think?” I asked him. “Don’t classify yourself,” he told me.

But classifying is a part of seeking your identity, at least at first. And everyone at my school was doing it. Most were emo. I also remember there were the skaters, metalheads, preppies, some rockers. There was everything.

But this story isn’t about me, about those of us who didn’t know if we wanted to be openly emos or not. It’s about those who did carry the label with pride. I present to you one of them: Ollin Sánchez, better known at that time as “el Mosco.”

[Ollin Sánchez]: My first contact, the first time I learned about emo was as soon as I entered high school. I was about 15 or 16 years old . . .

[Fernanda]: This was in 2006, when there was no fighting yet, no enemies of the emos. Ollin was, so to speak, one of the first waves of emos of the early two thousands in Mexico City.

[Ollin]: Well, it was almost in baby steps, that emo thing. We were barely inventing it and . . .

[Fernanda]: At the time, people weren’t paying much attention to them. They were small groups of friends who talked about music, about their lives . . . who secretly drank and wandered down the streets together to hang out. The teenage dream.

To create their aesthetics, they imitated the style of the bands they liked, took ideas from their friends’ clothes and also looked for inspiration on MySpace. There were photographs of emos from other countries, especially the United States, showing their hairstyles and the way they dressed. But most of all, the music . . .

[Alejandro Castillo]: In fact, MySpace was the place where you went to know bands. And you could get their music.

[Fernanda]: That’s Alejandro Castillo, the “Bake”, one of Ollin’s best friends at the time. He was a fan of Japanese culture, especially music. And the emo looks caught his attention.

[Alejandro]: Tight pants, black t-shirts, eyeliner. Let’s say looking a . . . a little androgynous, and that’s what I found in Japanese bands . . .

[Fernanda]: There were also references from the United States: My Chemical Romance, Paramore, Fall Out Boy . . . And some Latinos: PXNDX, Delux, Kudai . . . a lot of bands that played pop-punk, metal, screamo and post-hardcore, which is this genre of rock with dramatic guttural screams, Alexander’s favorite.

[Alejandro]: Yes, there are things that at some point you want to express but you can’t find the best way to express them, just as they say—you want to scream.

[Fernanda]: Unlike punk, which usually talks about rejecting the system and politics . . . the lyrics in (quote) emo music spoke more about intimate conflicts, about our emotions, of course.

Over time, the emo trend became widespread. They were no longer isolated groups of friends in schools here and there. Suddenly malls, parks, public plazas—streets in general were full of emos. No one knew where they came from, but cities around the country were being taken over by teenagers with long bangs.

The emos adopted specific spots in the city and these became their hangouts.

[Ollin]: The first place we started to meet was in El Chopo.

[Alejandro]: I started to get together with a group of friends at El Chopo. El Chopo is a public market here in Mexico City that happens on Saturdays.

[Fernanda]: El Chopo is a street market with dozens of stalls selling crafts, clothes, accessories and most importantly, music—lots and lots of music. Not only is it sold, albums are also exchanged; concerts and cultural events are organized.

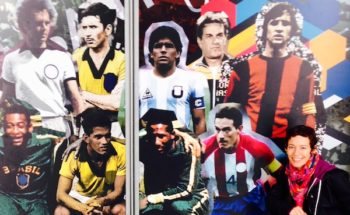

[Daniel Hernández]: El Chopo is historically, since the eighties, where all the subcultures of Mexican youth meet. The different countercultures, the bands, come together and link up: the punks, the skatos, the rappers, the pachucos.

[Fernanda]: This is Daniel Hernández. He’s a journalist who is currently with the LA Times. But back then, he was writing about the subcultures of Mexico City. And at the time when the emos began to visit El Chopo, he spent time there investigating.

[Daniel]: And suddenly you saw it, I saw it with my own eyes, like a new fashion trend, these kids were wearing very tall fringes in the back or the front.

[Fernanda]: And that look caught the eye . . .

[Daniel]: That is, of the groups that were already established: the goths, the punks, the skinheads or the hardcore rockers. As for the emos, it was kind of funny.

[Fernanda]: They thought emos were a poor imitation of themselves. An attempt to copy something from everyone and get nothing of their own.

[Daniel]: So, it was . . . um . . . here you feel a bit of social tension.

[Fernanda]: For the vast majority of the established groups, emos were superficial children and nothing more, but some took it personally. That’s why the anti-emo movement started, with calls to hit them and everything else. And the first place they wanted to kick them out of was precisely El Chopo.

This is Ollin.

[Ollin]: We were not well received, that’s how it was as soon as you arrived: harassment and insults. And well, they pushed us out, just like saying, “You can’t be here, go away.”

[Fernanda]: So they had to give up El Chopo. These are some of the anti-emos of the time, speaking on television interviews:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Punk 1]: That is not a movement, that is not culture. You talk to me about culture, I’m a Mexica.

[Punk 2]: Not because they’re discriminated against. They take depression as their main ideology, and depression is not an ideology; it’s an illness.

[Punk 3]: They’re taking things from different cultures, and they don’t know shit [censorship beep]. They don’t know, they haven’t begun to investigate what the hairstyle means, what the boots mean, they don’t know anything. They’re doing it just as a trend. A few years ago there weren’t any, and now if you’re lucky, you’ll see only fifty emos a day.

[Fernanda]: Over time, the atmosphere of tension against emos grew, outside the Chopo and outside the schools. A key moment in this transformation was when this monologue was broadcast:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Kristoff]: Emo is silly. What is emo? It’s a thing for fifteen-year-old girls.

[Fernanda]: This is Kristoff, a host on Telehit, one of so many music channels, trying to be like MTV. The channel was very influential among teenagers . . . Its presenters were public personalities, and what they said was relevant . . . That explains the importance of Kristoff’s words; he was one of the stars . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Kristoff]: They just get excited because they love the singer in the little band, not because they like music, number one. Number two, is it really necessary to create a new genre to express emotions? Isn’t death metal enough? Don’t we have enough with punk? Don’t we have enough with Camila, Sin Bandera, José José?

[Fernanda]: During his research, Daniel Hernández was able to talk with him. This was his reaction upon remembering it:

[Daniel]: Kristoff [laughter]. Oh no, Kristoff.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Kristoff]: It is necessary to create a new genre that says, “Dude, everyone else is wrong, emotionally they don’t satisfy us.” Fucking bullshit, kids, there is no movement there, no way of thinking, no musicians.

[Daniel]: Kristoff was, well, sure, a macho presenter, like . . . a rocker, right? Mainstream rock, but he sees himself as . . . alternative? (laughs)

[Fernanda]: That image, the one that Kristoff radiated, was the one that some rockers wanted to keep, especially the anti-emo ones: strong, tough, superior, annoyed by these emotional teenagers. The monologue that Kristoff did that day became what would now be called viral; it reached many people.

[Daniel]: And I think that many other Mexicans and young people who were not emos felt identified with that clip; they were inspired to take Kristoff’s words and apply them directly to emos in whatever town they were.

[Fernanda]: Ollin and Alejandro say that after being expelled from El Chopo they looked for another place to make it their meeting point. One of their friends invited them to the bar where he worked: Los Sillones.

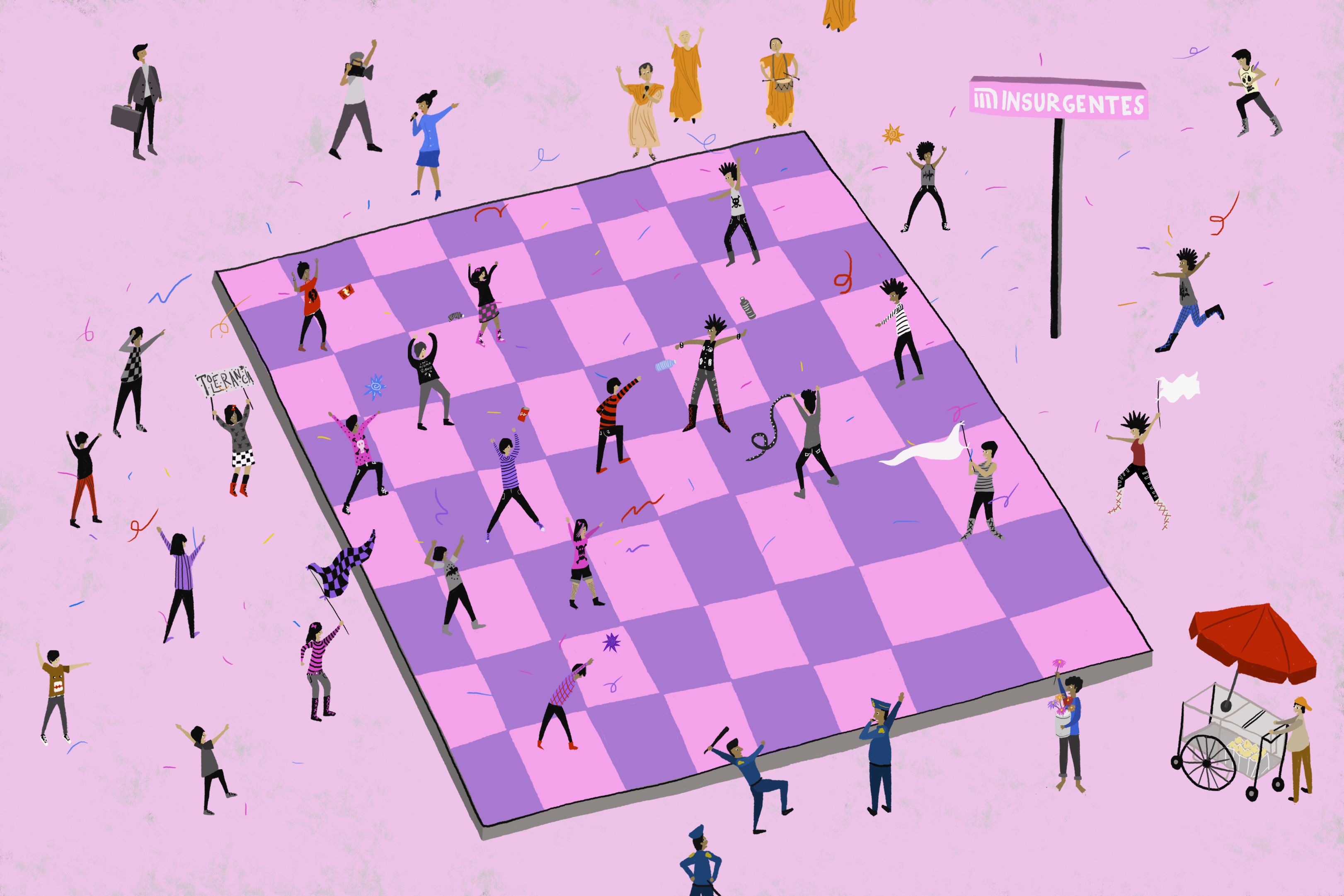

It was a tiny bar that sold beer, played the music of the time, and was one block away from the Glorieta de Insurgentes. And for those who have never visited Mexico City, I will tell you what the Glorieta is like. It is a large circular, open-air plaza, where thousands of people move daily. Along the edges are shops and stands with food, clothing, pharmacies, internet cafés, and at that time there was even a place with video-game machines. It’s always busy because it’s the exit of the Insurgentes Metro Station, one of the most important and central stations in the city.

And well, the bar was called Los Sillones because it was literally a place that only had a couple of chairs to sit and drink. Nothing else. It was pretty shabby, that is, not well taken care of.

[Ollin]: In other words, everyone came to the Glorieta because a few of us got to the famous Sillones that was like a . . . a little place that later became like a clandestine bar, or something like that, because we were all minors, and we drank there.

[Fernanda]: You can imagine why it was popular. Los Sillones became the new exclusively emo meeting point. Of course, there was no sign on the door saying that only emos could enter, but the appropriation of the place was obvious. Daniel Hernández, for example . . .

[Daniel]: I could never enter Los Sillones, really, I couldn’t enter. I felt like it was a place where you literally had to have bangs to get in and . . . (laughs).

[Fernanda]: So, the emos began to meet at the Glorieta and from there they went to Los Sillones. And since it was too small for an army of emos, it was always bursting. A lot of them didn’t go inside the bar but just hung out in the Glorieta, talking and listening to music.

That plaza and that bar became a hangout for emos, a place where finally nobody bothered them, where they had a second family of friends, which at that age is very important. And where they could finally just be.

[Daniel]: Now they had a geographical point, you know what I mean? They now had places where this new little group could claim some public space. I think in Mexico City there is always a discussion about conflict over public space. It’s always a topic in the city, you know?

[Fernanda]: In the eyes of the more dogmatic punks and anti-emos, this was a threat. Not only were they, in their own words, copying their style, now they were also taking spaces in the city. So, they were not going to give up the Glorieta to them so easily. Again, Ollin:

[Ollin]: Punks would go there to the Glorieta to . . . people said, to chop hair. In other words, they went and literally cut your bangs off.

[Fernanda]: They chased them . . .

[Ollin]: And anyone who was caught was beaten and their bangs cut.

[Fernanda]: In addition to the beatings, cutting their hair was extremely violent to me. Keep in mind that the emos were adolescents 13 to17 years old, while the punks were older, young people in their twenties messing with younger kids.

While emos remained a massive fad, no space they adopted across the country was a safe place for them. With a boost from the internet and the media, hatred of emos was no longer a small matter.

[Daniel]: And suddenly in many other cities throughout Mexico there is a shitload of emos and also a shitload of people saying or declaring themselves anti-emo.

[Fernanda]: They would set a specific day and hour to go out and beat up emos. One of the first times was in Querétaro, about two hours from the capital.

This is Alejandro:

[Alejandro]: Some were already scared because a video from Querétaro had been shared, showing some emo boys being beaten in a plaza.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Anti-emos]: He wants to cry, he wants to cry, he wants to cry!

[Alejandro]: So, you can see why they were scared, right?

[Fernanda]: I remember the fear. For me it came with a video that a stranger shared via cell phone with my entire class. A young woman was seen being hit on the head with a brick. No one had to explain the context to me. From her appearance, her hair, I understood that the girl was emo. We were all shocked. It was the topic of conversation the entire day and also one of the main reasons why I decided not to be emo, even though I loved the style. It was not until now, researching this story, that I learned the video actually came from the Middle East and not from Mexico. But the level of persecution this group endured made it seem completely viable in my country.

The first video, the one of the beatings in Querétaro, was sent around in Mexico City with the threat that the same thing would be repeated here. In MySpace and by email, an image with a black background and white letters began to circulate. It read, “Be a patriot—kill an emo.”

From incidents like the one in Querétaro and the calls for violence that circulated on the internet against emos, it was obvious that things were getting out of control.

Even Kristoff, who had previously made fun of emos, now went out to try and calm things down a bit. In his own way.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Kristoff]: Why do they mess with emos? They mess with emos because emos don’t defend themselves, dude, because they’re into their damn shit. Leave them alone, dude, what’s the big deal? What balls do you need to get together on the internet, dude and fuck up three poor emo bastards? What the fuck did those kids do to them? What the hell did those kids do to them?

[Fernanda]: And he ended with this:

[Kristoff]: I may not agree with what emos think or what other people think, but I would die, man . . . I would die to defend the rights that those bastards have to express themselves. Thanks. Damn! (applause) fucking idiots . . .

[Fernanda]: But it was too late. There was already a call for a beating in Mexico City on Saturday, March 15, 2008 at 3 p.m., at the Glorieta de Insurgentes. It was only a week after the incident in Querétaro.

That Saturday afternoon was clear and cloudless. This was one of the people at the Glorieta de Insurgentes that day:

[Salvador Castro]: My name is Salvador Castro. I’m from here in the city. I’m 32 years old.

[Fernanda]: Salvador, who was 19 years old at the time, and one of his friends had decided to go play the arcade machines at one of the stands in the area. Neither of them was emo as such, but they enjoyed the same music and looks, so they knew emos and punks well. Salvador’s friend tried to warn him, telling him there would probably be trouble that day and that they’d better go elsewhere, but Salvador reassured him.

[Salvador]: There won’t be anything . . . nothing will happen. Three fucking metalheads are going to come and want to beat up ten guys. And the other guys are not going to do anything. That is, they’re just going to yell at them.

[Fernanda]: While they played on the videogame machines, little by little the Glorieta began to fill up, even more than usual. If on a normal day there were between fifty or one hundred emos, that March 15 there were more than two hundred . . .

[Salvador]: So, we went out and saw . . . too many already . . . there were too many emos. It was like hey, there’s going to be a tocada, or what’s up?

[Fernanda]: Tocada means concert. That afternoon, Ollin and Alejandro were in Los Sillones. Alejandro had prepared a party for that night, and they were looking forward to it. They tried to relax like any other Saturday, but they couldn’t ignore that the atmosphere was tense. Many in the bar were afraid that punks would show up.

[Ollin]: The truth is I did not take it too seriously; I thought it was not going to happen. We were in this bar that I’m telling you, Los Sillones, when . . . when actually, we began to hear that yes . . . they were arriving.

[Fernanda]: The emos in Los Sillones got up and joined the rest outside. They began to talk until a noise interrupted them: From one of the entrances to the Glorieta, shouts could be heard approaching in the distance.

[Salvador]: At that moment we see that some . . . some darketos and some metalheads were coming, with some punks who were wearing chains. And I said to him, “Oh shit, I think there is going to be a stink, dude.” My friend said, “Bullshit, no way.” “Well, I’m telling you, dude.”

[Fernanda]: The Glorieta split into two camps: the emos and the punks. The advantage the emos had was that they vastly outnumbered them. There were fewer than 20 anti-emos, punks and mostly metalheads, against more than 200 emos.

One of Ollin and Alejandro’s friends tried to avoid the confrontation. He approached the opposing group and said:

[Alejandro]: What, what do you want here? That they were being a nuisance. That we weren’t doing anything, and that they should leave.

[Fernanda]: But despite being at a disadvantage, the punks did not intend to back down. They yelled threats at them.

[Salvador]: They started yelling, they were yelling, “Well, I’m going to beat you up, I’m going to kill you. Now you’ll see, motherfuckers.” And the . . . the emos replied saying, “Well, cámara, dude, go right ahead.”

[Fernanda]: “Cámara” is like saying “go ahead.” The police approached the area to try to impose peace with their presence and prevent the situation from ending in a brawl. But nobody cared.

A group of emos quickly started looking on the ground for whatever they could find to defend themselves and push the punks back.

[Salvador]: And they were throwing bottles . . . trash. In general, they were just throwing trash.

[Fernanda]: A television reporter had already arrived on the scene, and her cameraman was recording everything that happened.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Reporter]: The emos responded by throwing bottles that hit some of the other gang members.

[Fernanda]: Thus began the first wave of blows. Ollin went to a safe area, trying to avoid the aggressions. But Alejandro ran after one of his friends to defend him, and managed to free him from one of the punks.

[Alejandro]: I get behind my friend, I pull him. And well, sure enough, just like that, in the heat of what was happening, I got there and hit the other guy and he falls down together with his girlfriend.

[Fernanda]: Salvador couldn’t believe the emo teens were responding with blows.

[Salvador]: And it was very . . . very strange to see . . . see the sensitive ones being aggressive, right? All the emo kids.

[Daniel Alarcón]: The issue is that in the eyes of everyone, the emos were docile. But hey, there they were, responding to the attacks, to the surprise of onlookers, and of course, the punks.

And the battle was just beginning.

We will return after a pause.

[MIDROLL 2]

[Daniel Alarcón]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

Before the break, we heard how harassment of emos in Mexico had been increasing for years . . . Until everything exploded in March 2008, with violent attacks in several cities, and a battle between urban tribes in the Glorieta de Insurgentes, a very busy and central point in Mexico City. Bottles and trash flew through the air like projectiles. The punks, who had come to attack the emos, to their surprise found themselves cornered.

But the battle continued. No one was ready to give up.

Fernanda continues the story . . .

[Fernanda]: After hitting and knocking a punk to the ground, Alejandro crossed the battlefield and returned with Ollin and his group of friends. The plan was to defend themselves as best they could from the punks, who—far from surrendering—kept fighting and throwing insults. This is how Alejandro and Salvador remember it:

[Alejandro]: Fucking emos, assholes, faggots and things like that . . .

[Salvador], “You’ll see, you son of a bitch, I’m going to bust your entire fucking snout, you fucking emo.” I remember it like that, exactly what I heard because I even turned around to see the metalhead, “Oh, hey dude, calm down.”

[Fernanda]: Eventually, the two sides ran out of steam and they all needed some air. There were insults crossing from one side of the Glorieta to the other, but the blows stopped.

[Salvador]: They had taken some kind of a break since they got tired of fighting with everyone, and they were sort of licking their wounds.

[Fernanda]: It was a moment of truce, and the police took advantage of the break to try to disperse both sides. Two hours passed, long enough for everyone to think the conflict was over. But the peace was temporary. Out of nowhere, someone dropped a blow with a belt and then . . .

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Reporter]: The second confrontation . . . (Sound of conflict in the background). The women on both sides were transforming into beasts. They were ready with belts in their hands, when suddenly . . .

[Fernanda]: During the pause, the punks got reinforcements, but the emos were still a majority. Let’s remember that they had suffered years of bullying and harassment. There came a point where all they needed was to get even; it didn’t even matter against whom anymore. The violence was no longer a matter of sides.

[Salvador]: It started to be like a pitched battle, where they were hitting everyone, that is . . . everyone against everyone.

[Fernanda]: Eventually, the police took control of the situation to separate them and surrounded both the emos and the punks, but they weren’t very sure what the conflict was about or who were the ones who were fighting.

A policeman was interviewed in the newscast:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Police]: People of different beliefs were detected there, people of different cults, and we tried to separate them to avoid any aggression from both camps.

[Fernanda]: They could no longer hit each other, but the tension and the screaming continued in the distance. Finally, what worked to dissolve the conflict was an unexpected distraction . . .

[Reporter]: Suddenly, as if it were a joke or a surreal film, songs and music were heard coming out of the Insurgentes subway. It was a group of Hare Krishna and believe it or not, they drew away people’s attention.

[Fernanda]: They were men wearing orange and white robes . . . Every Saturday, they would set up a musical presentation at the Glorieta de Insurgentes.

[Ollin]: They got there and it kind of calmed the situation down a bit . . . It kind of got us out of the mood.

[Fernanda]: And amidst the bottles and trash, chants and tambourines could be heard while the police evacuated everyone. The place was finally deserted.

There were no serious injuries. Alejandro, Ollin, and Salvador returned to their homes safely. But news of the beatings spread to the other subcultures of Mexico City.

[Darynkayna Marín]: Everyone found out what was happening there and we said, “What’s wrong with them?”

[Fernanda]: This is Darynkayna Marín. She is 37 years old and from the age of 16 she is goth or gothic . . . she dresses almost entirely in black, with comfortable clothes or velvet dresses, stockings, boots and a lot of makeup. Much of her skin is tattooed. Her accessories are jewelry with skulls, bats and bones . . .

[Darynkayna]: My curtains are purple; my furniture is black. Pretty gloomy for ordinary people, and maybe some people will not feel very comfortable here, you know?

[Fernanda]: When she and her goth friends heard about the attacks on emos . . .

[Darynkayna]: We were pretty annoyed here, on the side of . . . on the dark scene.

[Fernanda]: At that time, goths were known as darks, and even now the terms are interchangeable.

[Darynkayna]: We used to meet at the Tianguis Cultural of El Chopo. We met there every Saturday from 9 in the morning until 5 in the afternoon, making fanzines, creating art, and so on.

[Fernanda]: And of course, the conflict over emos was a recurring topic of conversation at El Chopo. As members of the alternative scene, they felt very concerned about everything that was going on.

[Darynkayna]: In reality, it turned into indignation. How was it possible, if we consider ourselves empathic people, if we also suffer some discrimination from sectors of society because of our way of dressing . . . And attacking other people for something so absurd as how they dressed didn’t… didn’t go well with our . . . our ideas, right?

[Fernanda]: But they remained as observers at a distance. Until one day . . .

[Darynkayna]: Hmm . . . one weekend at El Chopo a lady arrives, who is also dark . . .

[Fernanda]: Her name is Angélica González, or Angy:

[Angélica González]: Luna Negra is my pseudonym; my age, half a century. I belong to the old guard of rock and roll.

[Fernanda]: She was 37 years old at the time.

[Darynkayna]: And she has three daughters. One of them is punk, the other is emo and the third is ska. And she’s . . . well, she was the goth mom. A very alternative family; that was held in a lot of esteem in the Chopo community.

[Fernanda]: The daughter who was emo was 14 years old. At first, Luna Negra wouldn’t let her go alone to the Insurgentes Glorieta. To protect her, of course. She knew about the beatings, the chopping off bangs, the insults and harassment, and she did not want anything to happen to her.

But she did accompany her, and there she got to know many of these teenagers well, she listened to them, guided them . . . she basically adopted them.

[Angélica]: It got to the point where they called me the dark mom.

[Fernanda]: In fact, that Saturday of the battle at the Glorieta de Insurgentes, Luna Negra was there . . . She watched the violence, full of indignation . . .

[Angélica]: The cool groups of punks of . . . of yesterday, those didn’t go around with bullshit saying, “We are going to beat a child.” They were sheep, all those persons who beat up the emos were sheep.

[Fernanda]: Meaning, not real punks, but people who follow something because it’s the trend, in this case beating kids just for fun.

[Angélica]: Defend your country, damn it. Fight against the repression of the people. Why would you go around fighting because they dress or don’t dress? It’s all bullshit.

[Fernanda]: Her daughter was not beaten in the battle at Insurgentes, but she was on another occasion, while she was walking down the street with her friends.

[Angélica]: And suddenly we were there in El Chopo with the whole gang and some emos came running: “They beat up your daughter.”

[Fernanda]: For her, that was the breaking point. Not only because they beat her daughter and her friends, but because the media was also pointing at them, all the “punks and darks,” as the aggressors.

The dark scene wanted to help the emos and show that their group were not aggressors. That day in El Chopo, when they came to tell Luna Negra that her daughter had been beaten, Darynkayna felt that it was time to stop all this. It was March 22, a week after the confrontation at the Glorieta.

[Darynkayna]: At that moment I said, “You know what? Let’s go right now to the Glorieta de Insurgentes, and let’s talk to the kids.”

[Fernanda]: To tell them it was time to set things straight. Enough of the violence and aggression.

So the punks, darks, goths and metalheads went with Luna Negra and Darynkayna to the land of the emos. Imagine the scene: a lot of people dressed in black, with studs, those spikes that punks and darks put on their clothes, wearing extravagant hairstyles, boots, and looking tough, walking through Mexico City, angry, outraged . . . So intimidating was their presence that when they reached the subway, the police let them in for free, out of fear that they would cause damages.

There were about fifty of them, and they filled a whole subway car. Darynkayna came up with an idea to make sure the emos didn’t think they were going to attack them: a symbol of peace.

[Darynkayna]: An improvised white flag made out of my husband’s t-shirt and attached to an umbrella. (laughs)

[Fernanda]: But when they reached the Glorieta, many emos were scared and ran. Darynkayna, Luna Negra, and the others quickly came over to speak to those who remained. They explained that not all punks and darks intended to beat them, that they supported them and wanted to help.

The meeting began to take the form of a political rally of urban groups. Darynkayna approached the journalists who were there and spoke. This is a recording from that day:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Darynkayna]: That’s why we came, to ask you not to be afraid of us because we did not come to attack. We want to talk to you so that you realize that we are never going to attack you physically, verbally or in any way. We punks, darks, and metalheads won’t have the TV Azteca and Televisa television stations slandering us and saying . . .

[Demonstrator]: It’s not true!

[Darynkayna]: . . . that we are aggressors. They have always demonized us.

[Demonstrator]: Bravo!

[Fernanda]: Word of what was happening at the Glorieta spread, and people from various LGTB collectives who wanted to help began arriving at the place. And a representative of the government of Mexico City. An official, but improvised dialogue was held between emos, punks, darks, activists and the authorities.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Demonstrator]: Dark, emo, punk, rockabilly, or whatever we are . . . we are human . . . we have to respect each other . . .

[Fernanda]: This is an emo girl:

[Emo]: Well, how cool that they came and . . . how cool, let’s make peace, right? And we are going to unite against the government (laughs). How awesome.

[Fernanda]: Meetings with officials were scheduled so that alternative groups could express their concerns and so they could all together seek a solution to the increased violence against the emos.

Luna Negra and Darynkayna proposed to the emo kids that they organize a march to publicize their position and as an attempt to defend themselves peacefully. The darks also offered to mount guard at the Insurgentes Glorieta to watch if any of the violent punks were approaching and help the emos drive them away . . . This is how the media reported it:

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Reporter]: Finally, darks and emos made peace.

[Emos]: Tolerance, tolerance, tolerance! (growls)

[Darynkayna]: So it seems that . . . we had signed a peace treaty . . . The SOB’s! That is, we never signed anything. We were just trying to reconcile things so that the media would stop saying so many things that weren’t true.

[Fernanda]: On March 29, a march called “Respect for Diversity, No to Discrimination against Youth” was held. It was a beautiful, warm day. Several emos, some accompanied by their parents, others only by their friends, arrived with posters and shouted slogans.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Reporter]: Calling for tolerance and respect, 300 young people of the so-called emos held a march this weekend.

[Fernanda]: All of this may seem comical to us now, but Daniel Hernández, the journalist we spoke with earlier, attended that first mobilization and has a very different view.

[Daniel]: It’s very emotional for me, the way I saw them, like “look at these kids marching for their right to just be themselves”—which is something very basic and something that we can all feel and share.

[Fernanda]: The route went from the Glorieta to El Chopo, though many were afraid they might be received with violence and be driven out again. Luna Negra was respected and used her influence as a rockstar from El Chopo to speak to the leaders:

[Angélica]: I told them, “You know what? The open-air market of El Chopo is characterized by being a space open to all kinds of expression, especially everything that is known as urban tribes.” What was the open-air market of El Chopo becoming? It’s supposed to be a place open to all kinds of expression, a place that defends human rights, that defends the right to free expression.

[Fernanda]: She finally convinced them to let them end the march there. It was something symbolic to end the march for peace between the groups at the very place where their harassment had started.

When they left the Glorieta and began their walk, they realized that a large number of police officers were guarding them. It was unusual. Reports say there were 230 officers.

As they approached the entrance to El Chopo, they found a canvas turned into a sign that seemed to have been made in a great hurry and little paint, but the message was nice. It said, “Welcome to El Chopo, emos.” And a slightly larger one that read, “El Chopo is for culture and tolerance.”

But at the entrance there was also a group of anti-emos, not very happy about the arrival of an emo march and less so with so all the police around. The atmosphere began to get tense. And although one of the Chopo organizers was using a loudspeaker, saying that “all kinds of people are welcome to the place,” the conflict flared up once more.

The shouted threats and mockery began . . .

Listen to this shout: Anyone who doesn’t jump is an emo.

(ARCHIVE SOUND BITE)

[Anti-emos]: Anyone who doesn’t jump is an emo, anyone who doesn’t jump is an emo, anyone who doesn’t jump is an emo!

[Reporter]: When they reached the so-called melting pot of subcultures, metalheads, punks, goths, and darks greeted them with whistles, personal insults, and even the occasional thrown bottle.

[Fernanda]: Although they had stepped onto the entrance to the promised land for a moment, they had to move away from El Chopo in order to end the day in peace.

It was not what they wanted, but it was a victory anyhow. In the following days, by April, there were several meetings between authorities, the youth council of Mexico City and urban groups. Luna Negra and Darynkayna were there, helping to explain the magnitude of the problem and organizing strategies to solve it. As a result, the campaign “for the freedom to be young, live and let live” was launched. Discrimination against emos became an official state affair. Even the National Human Rights Commission published an investigation of the conflict.

[Fernanda]: Things did not calm down instantly; threats continued to be reported in different areas of the country, but teenagers were no longer facing the situation alone.

Investigations were opened to find the virtual organizers of the March beatings, and more activities were held in the campaign, such as concerts, contests, forums . . . Until one day we woke up and there were no attacks on emos, but that’s because there were no emos left to bother.

In what seemed like the blink of an eye, the emos were extinguished. You could no longer find anyone at the Glorieta, or in the hallways of my school, or in the plazas . . . Did they get tired of the abuse and renounce the emo banner? Did the anti-emos finally manage to scare everyone?

Actually, our generation just grew up. The oldest emos entered college and continued to build their identity in other directions. Daniel Hernández, who had been following the emos for a long time, also remembers that transition.

[Daniel]: I feel that many were starting on their paths to eventually find the cultures where they would remain.

[Fernanda]: Some emos became punks; others, goths; others, even skaters or rappers . . . or who knows . . . podcasters . . .

[Daniel]: Or even a neo-Aztec hippie. Or they came out as queer people.

[Fernanda]: For many, the emo phase was a place to explore their identity without being judged or having to hide. In Mexico, to date, there is a stereotype that men have to be very masculine, strong, apparently without feelings, tough . . . Anyone who steps out of that line could be labeled as gay.

But among the emos, no one judged your appearance or vulnerability. That was precisely the point: they had the freedom to be. The emo guys also spent time putting on makeup, something that was controversial.

[Daniel]: For the first time that I can recall, there were young boys, men, wearing eye makeup. And that, too, for some . . . hmm . . . Mexicans was something pretty gay, right? It was something a man or a boy should not do.

[Fernanda]: Quite probably, many punks and darks were genuinely angry because they felt that emos were plagiarizing their style . . . but deep down, perhaps those attacks, the harassment, the collective bullying was about something simpler, and more ingrained in Mexican society: homophobia.

The emo trend took over, and many men felt threatened by it. Remember Kristoff’s words: a “trend for little girls.” Or the insults that were hurled at them on the street: “fucking emo faggots . . .” which in Mexico is a very derogatory way of calling gays.

But unwittingly and probably unknowingly, emo teens questioned the status quo of males.

[Daniel]: The emos were proposing a break with gender norms and the . . . and the norms that we identify in a society that continues to be very macho—like Mexico’s— as something not for males, or something like that. This was also a point of conflict or of violence or attempted oppression.

[Fernanda]: And although emo never became an established, “official” subculture, like the others, the simple fact of questioning this masculinity made them legendary.

[Daniel Alarcón]: Daniel Hernández wrote about emos and punks in his book Down & Delirious in Mexico City, which compiles this and other incredible stories from Mexico City. Highly recommended. We have a link on our website. He currently writes about culture in the LA Times.

El Mosco and Bake, that is, Ollin and Alejandro, grew up and left emo behind. They were part of a band and are currently engaged in their jobs and their adult life.

Darynkayna and Luna Negra have not been able to return to El Chopo due to the pandemic. But they are still digitally connected to the alternative scene of Mexico City.

Special thanks to Roger Vela and Pablo Merodio. Also, to all the former emos, punks and goths that we consulted for this episode, thank you for your help.

This story was produced by Fernanda Guzmán. She is a production assistant for Radio Ambulante and lives in Mexico City.

This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Nicolás Alonso, Luis Fernando Vargas and me. Désirée Yépez did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri and Rémy Lozano with original music by Rémy.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Aneris Casassus, Xochitl Fabián, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Laura Rojas Aponte, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Emilia Erbetta is our editorial intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, and it’s produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program .

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.