The Cuban Suitcase | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: Hello ambulantes,

If you’ve been listening to us for years and have already donated, or if you discovered us a few months ago but have already become a member, then thank you, from the bottom of our hearts, thank you.

And well, if you haven’t had the opportunity to make your donation yet, don’t worry, there’s still time. We are in the campaign until December 31st. So, to encourage you, I want to ask you to take a moment and think about the episode you’re about to listen to. Think about what it took to produce it. The reporting, the interviews, the writing, the editing, the fact-checking, the sound design. And then, consider that we produce thirty episodes of Radio Ambulante per year, and fifty more of El Hilo. And behind each episode is a talented, hardworking team, committed to this journalism, and to this audience.

All of this depends on you. We want to continue producing stories like this, but to do so, we need your help. Only 1 out of every 100 listeners supports our journalism with a donation. We want to double that figure. Help us double that figure. No matter the amount, because every donation counts. Visit: RadioAmbulante.org/donate. Thank you. Here’s the episode.

This is Radio Ambulante, from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

This, like so many Latin American stories, is one of comings and goings. And also about complicated suitcases.

You might remember Karla…

[Karla Suárez]: Well, I’m Karla Suárez. I’m a Cuban writer.

[Daniel]: We met her five seasons ago, in an episode called Toy Story. It’s worth listening to again if you have time. But, in any case, what you need to know for today’s story is that Karla has been living outside her country for twenty-five years. She left when she was under thirty, in 1998. Before the nineties, Cubans could only travel for official matters or to study in a country of the former communist bloc. In the nineties, travel for personal reasons was authorized, although one had to request an “exit permit” and have an invitation letter from a family member or a Cuban abroad… or someone who justified the reason for the person to leave the country. So the journey, which was once a dream, gradually entered the lives of Cubans, and with it, the suitcase.

[Karla]: In the end, a suitcase is a very small thing, so choosing what to take is super difficult. But almost everything I took in that first suitcase is still with me.

[Daniel]: Karla lived in Rome for a few years; then she went to Paris, and for the past 13 years, she has been living in Lisbon. When she left Cuba, she carried relatively little, what could fit in a small suitcase. Three books. Some clothes, all for summer.

[Karla]: I have in my home bookshelf, which has been traveling with me for 25 years, a tiny bottle of whiskey, not even a whiskey I liked. But a friend gave it to me and said, “Drink it on the plane.” And I took it and drank it on the plane and kept the bottle. For me, that bottle is the journey. The journey I was going on, to live outside. And there it is on my bookshelf. That little bottle is always with me.

[Daniel]: During those years, a part of Karla’s generation also went to live abroad. They were the years of the so-called “Special Period,” a time of crisis that came after the fall of the Soviet Union. People started leaving the island however they could: through work contracts, marriages, tourism, or what is known as “internationalization missions,” meaning working in other countries through a contract with the Cuban government. In 2013, the requirement to request permission to leave Cuba was eliminated, although there are still Cubans who, for political reasons, aren’t allowed to either leave or return for a visit. From that moment on, however, the migratory flow began to increase in both directions. Karla left with a residence permit. And, since she left, she has returned whenever she’s been able to.

[Karla]: At first, I went every six months. Then I spent a few years not going, went every two years, then more years passed, and then…

[Daniel]: And so on. As I said, comings and goings. So many that Karla has lost count of how many times she has visited the island, her island, since she left. In the early years, every return home was a celebration. In a way, a vacation. Seeing friends, family, traveling around Cuba, going to the beach. Returning to a city she still considered hers.

And in her suitcase, she packed… well… you can imagine.

[Karla]: At first, look, the first suitcases. [I brought things for my parents. But my parents were young at that time were young. They were still strong. I brought, for example, gifts. A lot of gifts. I brought clothes for my friends. There were those who had babies, so I brought things for the babies.

[Daniel]: But over the years, things started changing.

[Karla]: It’s curious because, of course, when I went at first, I always found many friends, and every time afterward, every time I returned, there was one fewer and one fewer.

[Daniel]: What percentage of your friends from your generation have left?

[Karla]: Oh, I couldn’t tell you, but almost all. Some friends remain, some remain and would like to leave, but there are few. There are really few. My friends are… I find them on social media, in the countries I visit, on WhatsApp, like that.

[Daniel]: And with each acquaintance who left, the country to which she belonged, the Cuba of her youth, became, increasingly, an imaginary country. A country that existed in her memory or perhaps in the collective memory of a generation of Cubans who now live scattered around the world.

And each suitcase she packed for those return trips became a snapshot of life in Cuba: moments of apparent political openness and relative prosperity, and then periods of repression, precariousness, even hunger.

[Karla]: Little by little, over the years, more and more… I mean, the suitcase began to change, right? It was like, “I need this thing now, I need this. See whether you can find this.” I mean, for my family and for my friends. Then my parents, of course, started getting older too, and could no longer do certain things, and many items started to be scarce in the country as well. And so, of course, every time you went, you said, instead of putting in the suitcase, I don’t know, a little dress, because it’s so pretty, well, I better bring something that I know the baby or the toddler needs.

[Daniel]: And it’s not that each visit didn’t fill her with emotion; of course it did.

[Karla]: But of course, it’s like each time you’re returning to a country you no longer know. My… my journey has been changing for a long time; it’s no longer a vacation trip. People tell me, “You’re going to Cuba, oh, how nice!” And I say, “Well, for me, exactly, it’s not going to Cuba, it’s not ‘How nice, I’m going to the beach.’ It’s ‘I’m going to solve problems for people.’”

[Daniel]: Today we are going to accompany her on a trip to Cuba that she took in June 2023, to see what she finds, to see what problems she has to solve, to see whether what she packed in her suitcase is useful or not.

We’ll be right back.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back on Radio Ambulante. Karla Suárez continues telling us.

Here’s Karla:

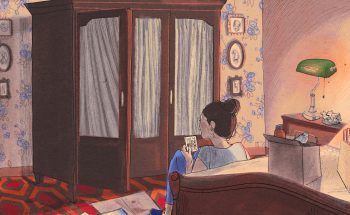

[Karla]: As I love to travel, every time I have to pack, I get excited. If my destination is Cuba, things are a little different. My journey begins with the suitcase, yes, but, as you’ve heard, it’s not just any suitcase. Mine is the emigrant’s suitcase. Making it is not a matter of hours or the night before departure, because it contains very little for me and a lot for others: family, friends, relatives of my friends, friends of my friends. Things that are needed and not easily found there.

Each suitcase is like an X-ray of the country’s condition at the time of the trip. That’s why every suitcase I’ve made for each of my returns to Cuba has been different. They have in common, yes, the way of preparing them. I usually start doing it on the same day I buy the travel ticket, sometimes even earlier. At first, I wondered why it took me so long. I thought it only happened to me, but over the years, talking to other Cubans, I understood that it’s a common thing. My friend Andrea, for example, has been living in Portugal for years and doesn’t even know how many Cuban suitcases she has had to make, but she knows it always takes time.

[Andrea]: Months. Months. And you keep buying, we keep buying, and we keep buying, and in the end, you end up like I do, taking suitcases and paying for extra suitcases with things that you realize don’t make sense for us; for me here, it doesn’t make sense, but you start thinking. You say, “For them, it makes perfect sense and much more.”

[Karla]: To try to organize all that is needed there, the first thing I do to prepare my suitcase is make a list. I write to my family and friends in Cuba asking them to tell me what they need. The priorities are more or less clear: first, medicines and food for children and the elderly. I’ll take what I can, of course, but I prefer to know all the needs rather than having to say later, “Why didn’t you tell me?”

People start responding. Some say they don’t need anything, but I insist because I know they’re ashamed to ask. Others need things that I didn’t even know existed, and I have to start looking for them. Sometimes they also ask for a friend or a relative I don’t know, but if it’s important, then I do what I can. As the travel date approaches, unexpected requests usually appear. And so, little by little, I start buying.

As usual, for my last trip, I made a list.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Karla]: Well, today I have to do the last shopping.

This is me, a few days before traveling to Cuba, checking the things they asked me:

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Karla]: Let me check the list and cross things off. This. It’s done. I found almost all the groceries. Powdered milk, skimmed and whole. OK. OK. OK. OK. I couldn’t find the filter for David’s house tank pipe. It’s a great pity. Oh, well… As for medications, I still need saline solution, furosemide, compression stockings, children’s ibuprofen, Yamilé’s mother’s items, and my aunt’s iodine. And I’m going to buy another paracetamol just in case. Well, almost everything is done, a little more to go.

When you call the home of a Cuban living abroad and they say they’re packing to travel to Cuba, you immediately respond: “Well, bye, we’ll talk when you can.” Because packing a Cuban suitcase is stressful, a nightmare, because you want to help everyone and that’s why you want to put more things than can fit.

(ARCHIVE SOUNBITE)

[Karla]: It’s important that everything is tight, and there are no movements within the suitcase.

I start packing several days before, to get a sense of the actual volume of what I have, and so I did on this last trip. I packed and repacked the suitcase to fit as much as possible. Some people come up with their inventions. My friend Guillermo, who has been living in Spain since the late nineties and also travels to Havana to visit his family, told me about his:

[Guillermo]: Well, I buy a bag that they sell that is plastic. It’s a plastic that is a bit strong. I mean, it’s not a supermarket plastic bag. It’s a slightly stronger plastic that weighs nothing. And so, in this way, I save the weight of a suitcase. A suitcase can weigh about four or five kilos. So I fill this bag. I try to put on the outside what can take hits like fabrics, clothes, cans that can take hits and not break. And in the center, what is more fragile.

[Karla]: In my case, I usually carry a briefcase that is sturdy but quite light. And before starting to pack, I take everything out of the cardboard packaging to eliminate unnecessary grams of weight and study how I can protect fragile items, what I can put inside what, things like that. I remember once I had to take a cage for my mother’s cat, but it had a rigid structure and didn’t fit in the suitcase. So what I did was fill it with the medicines I brought for people and wrapped it with the pareo (sarong) that a friend had asked me for. That was my carry-on luggage.

This time, one of the challenges was bottles of cooking oil, but my sister had a great idea. She also lives abroad and has experience with this type of suitcases.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Sister]: Look. Do you remember she has those diapers?

[Karla]: Ah. Can I put the bottle of oil inside the diapers?

[Sister]: We take the diapers out of the diaper package, take the diapers from the middle. Put the two bottles in there, and that’s it. If something happens, the diapers…

[Karla]: If something happens, a diaper absorbs the oil. OK, go ahead. Perfect. Yes, I’m going to do it that way.

In the Cuban suitcase, everything has to fit perfectly. On this trip, almost everything I brought was food and medicines, because that’s what’s needed now. I mentioned earlier that each suitcase is like an X-ray of the country. In previous years, I’ve brought tools, wall paints, even small IKEA furniture. But now Cuba is going through another economic, social, and political crisis. Very severe this time, only comparable to the one experienced in the 1990s. In 2023, what is urgently needed is food and health. In fact, this time, all the requests made to me were for medications. And I never say no to that, even though the weight keeps increasing. Weighing the suitcase always gives me anxiety.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Karla]: And now let’s see how much it weighs because that is essential. So we close, push. It’s closing. Good. And we close the other. And now we weigh it. OK, perfect. I’m at 20. Perfect. It still even fits a little more.

[Karla]: The airlines I travel with allow a suitcase of 23 kilos in economy class. Any overweight or a second suitcase has to be paid for. A few years ago in Cuba, something happened that I don’t think happens anywhere else in the world: when you arrived at Havana airport, they weighed your luggage, and if you had overweight or a second suitcase, you had to pay again or give up some things. That also always caused me tremendous nervousness. So my concern about the suitcase didn’t end until I got home.

That changed over the years. And now, after the protests in Cuba in July 2021, they have eliminated tariffs for food, toiletries, and medications. They can be brought in without limitations, unless they are for commercial purposes.

This rule was intended to be temporary, but for now, it is still in force, and it has made it easier for many of us to bring more things than before. But on this last trip, I only brought one suitcase of 23 kilos. I had to buy a lot of medicines, and no matter how much I wanted otherwise, my funds didn’t allow for more.

Every trip, I swear that this time I will have the suitcase already closed before dinner the evening before the trip. But it never works out. That last night, I always find myself unpacking and repacking the suitcase. Anxiously rearranging things better, seeing whether what I have to leave out might fit in a little gap, because in the end, no matter how organized I think I am, I always end up having to leave things out.

When I finally finish, there is a great sigh of relief.

And then comes the flight.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Pilot]: The takeoff runway for today’s flight to Havana. After bidding farewell, the flight time will be 9 hours and 25 minutes to the destination…

[Karla]: I’m one of those who sleep peacefully on planes; I don’t need to take anything. Any means of transportation relaxes me, but when the journey is to Cuba, I can hardly close my eyes. I always go with a mix of joy and concern, like I carry my nerves on the outside. I walk through the plane, try to read, watch movies, talk to people in the bathroom line. That’s how I spend the hours until they tell us to fasten our seatbelts.

My Madrid-Havana flight landed on June 12 at 7:45 pm.

(SOUNDBITE DE ARCHIVO)

[Flight Attendant]: Welcome to Havana. Continue to wear your seatbelt until the seatbelt sign turns off…

[Karla]: It had been a year since I last went.

The first thing that always hits me when I get off the plane is the heat. That sticky Caribbean heat. As if the city were saying to me, “Welcome home. From this moment on, you won’t stop sweating.” In Cuba, the air conditioning doesn’t work well in many places; sometimes, it doesn’t even work well at the airport, so you have to sweat. Besides the heat, there’s something else I notice right away, but I like it more: the Cuban accent. Maybe it’s because I’ve been living abroad for a long time, or because I interact with people from different places and ways of speaking, but the melody of Cuban speech awakens good feelings in me. It makes me feel comfortable, brings me back to who I am.

[Karla]: The airport is not very large if we compare it with other international airports in Latin America. Dragging my small carry-on suitcase, I walked through the corridor that by now I’m familiar with. It has a glass wall. On the other side is the hall with the boarding gates, the cafeteria, and a few shops. I always walk fast to try to get to immigration early and avoid a very long line. But I can’t help looking at the people on the other side. They are the ones leaving the island. Many tourists and also many Cubans. On this last trip, it seemed to me that there were more Cubans than tourists.

There’s something I can never stop thinking about when I’m at the airport: What will people do after getting on the plane? Cubans, I mean. What will they do? Where will they go? Some will return for a visit. Others may never return because they don’t want to or can’t. Because, even though traveling is easier now, some Cubans still face restrictions upon leaving or entering. I think of Abraham, with whom I spoke shortly before my trip to Havana. He is thirty-four years old and has been living in Barcelona for almost two years. In Cuba, he was an independent journalist, writing about the country’s reality, and one day he had to make the most terrible of all suitcases: the one for exile. When I asked him what he jad taken with him, he said:

[Abraham]: Basically, I came with one suitcase, with the essentials.

[Karla]: Which would be…

[Abraham]: …with the three or four shirts I liked. I think I brought one pair of pants and one pair of sneakers that I was wearing. Everything else… I gave away all the shorts, the shirts. I play… I really like soccer, sports; I gave away all that I played with there. I think I brought… in fact, I see one suitcase of three books here.

[Karla]: Abraham told me he knows he can’t go back, at least not in the short term. As I walked through that airport corridor, I couldn’t help but look on the other side and try to imagine what kind of suitcase the Cubans there could be carrying. Would they be the ones returning or the ones not? Who knows.

There weren’t many people at immigration, fortunately, so I quickly exited to find my suitcase. Everything is always a bit chaotic there. Suitcases come out from different places. I spent time changing carousels to see which one mine would come out on. Some people shared a cart. One person watched it while the others moved around, like me. And you could hear shouts: “Here comes one,” “The big one hasn’t come out yet,” “How many did you bring?” Finally, mine appeared, I put it on the cart, and I left.

In the early years, my parents always picked me up. Many Cubans have that custom: if someone arrives from abroad, you have to go and meet them. I never called my parents from inside because, first, they didn’t have a cellphone. Then, when they could have one, I didn’t have a Cuban number, so it was impossible. But it didn’t matter; I knew that as soon as the glass door opened, I would see them in the front row, with excitement painted on their faces. Now I finally have a Cuban number, I’ve had it for a long time, but my parents don’t wait for me outside anymore. He passed away. She is no longer up for that kind of hassle. So, when the glass door opened this time, I saw other parents waiting and so many children and so many emotions. I smiled for them and continued my way.

One of the things I liked about returning was that the journey from the airport to my house was like a recount of my life. The taxi had to pass by my university, Cujae, where I graduated in electronic engineering. And I could even see, through the window, the student house where the literary workshop I attended in those days was held. Then, we passed by the music conservatory where I studied guitar in high school. Finally, at the corner where the taxi turned to enter my street, was the primary school where I learned to read. I always experienced this journey as my personal journey to the seed. As if the city were telling me, “I remind you of who you were so you don’t forget who you are.”

But on this last trip, it wasn’t like that. A taxi driver I had talked to on WhatsApp before leaving Lisbon was waiting for me outside. He had a sign with my name. Before going to the taxi, he asked for my address, and when I gave it to him, he said he preferred to take another route. The issue was safety. It was night, and in Cuba, there are now many problems with electricity. Power outages last for hours. According to him, that area could be completely dark, and he didn’t want to risk the car breaking down and us being left stranded, because we could be robbed. “Some neighborhoods are getting dangerous,” he said. “It seems you’ve been away for a while, but things have changed, people have needs, and that increases crime.” I didn’t dare to insist. “And did you only bring one large suitcase?” he asked. I nodded. He repeated that it looked like I had been away for a long time, and set off in search of the taxi.

There I stood, looking at those coming out. Some people had balls wrapped in plastic, like the ones my friend Guillermo makes, and others had a lot of suitcases. Cristian, the nephew of a friend of mine, told me how he stocked his family for a good while. He now lives in the United States, but during his last years in Cuba, he went abroad several times to visit relatives and, incidentally, return with products to fill his pantry. That’s the family suitcase.

[Cristian]: I come with five suitcases of 23 kilograms. And with 95% of food, practically: milk, spaghetti, tuna, and that’s it. Basically that, but in large quantities.

[Karla]: I arrived at the apartment roughly after ten. My friend, who has been helping us for years and is almost like a sister to me, was waiting for me downstairs. We took my things out of the taxi. Mom was watching us from the balcony. We went up, and then came the hugs, the conversations, the taste of some delicious things that came out of my suitcase, the laughter. I don’t know whether everyone experiences this, but every time I arrive at the place where I grew up, I have the feeling that the one going to bed that night is a younger version of myself. It’s just a feeling, of course, but I like it.

[Karla]: My father was the one who always fixed all the problems in our apartment. Fortunately, I inherited his skills for repairing things, so when he stopped being able to handle everything, I took over. My mother writes down the problems, and then I take care of them. That’s why, for a while now, I’ve been saying that my trips to Cuba are “thematic.” One trip is about carpentry, another about plumbing, the next about cracks in the walls, and so on. Of course, I can’t fix everything.

The “theme” of my last trip was electricity, something I couldn’t resolve. That’s why, the day after my arrival, a electrician friend with whom I had already arranged to meet came to visit. Out of my suitcase came the fifteen meters of cable he had suggested I buy to replace the one leading to the apartment, which was in very bad condition. The problem was solved in a matter of hours. But on that same day, I realized that my Cuban cell phone line had expired. At home, there was an old cellphone with a full-size SIM card, so I had to go to the telephone office to exchange it for a micro-SIM and put it in mine. For the moment, my mother lent me her cellphone.

The next day, I called the relatives of my friends, to whom I had brought gifts, to let them know I was in Cuba. They started arriving. Every time I’m with a relative, I feel as if, somehow, for that person, seeing me is like seeing, a little bit, their daughter, brother, mother, or whoever is on the other side. The same thing happened to my parents when I sent them packages with someone else. Families can talk on WhatsApp, even see each other through video calls, but it’s never the same. Kissing a friend’s sister on the cheek is like kissing her with the same kiss my friend left on my cheek when we met.

And so, the first three days were about deliveries and emotions: being at home with mom, seeing some of my great friends. I have a couple of friends who always come to my house the day after my arrival; we’ve known each other for a long time, and their children are like my adopted nephews. Seeing them is always a party. I had brought coffee to offer to all the visitors and bought beers on the corner. I only went out to go with my people from the conservatory to the concert of one of my musician friends, El Trombón de Santa Amalia and his group.

And also to the telephone office. I couldn’t resolve my line issue that time, but I didn’t give it much importance. The most serious problem, the “theme” of my trip, which was electricity, had been resolved quickly. The rest would be trivialities. That’s what I thought.

But on the 6th day after my arrival, the downstairs neighbor told me that the tank in my house was damaged because water was leaking into his apartment.

Here I must make a small explanation. Like in other countries, in Cuba, buildings have tanks on the rooftops to supply water to the apartments. At least in theory. The thing is that there have always been problems with water supply in Cuba, and in many neighborhoods, it doesn’t come every day. When I was a child, we had a water reserve at home, filled with a hose, and when the water didn’t come, we had to bathe with a bucket and a ladle. Now, Cubans install extra tanks on the rooftops as an individual reserve for their homes.

In my building, in addition to the four original tanks, there are eight installed by the tenants. The weight on the roof is enormous, but for now, it’s better not to think about it. In my neighborhood, water comes every other day. So, on the “water day,” as it’s called, all the tanks get filled. On the day it doesn’t come, each tenant uses their reserve. When my neighbor notified me about my tank, I went up to the roof with him to check it. He determined that it had an issue with the float. And, in case you didn’t know, the tanks work just like toilets. When the water level rises, it pushes the float up, and when it’s horizontal, the float closes the water inlet, and no more water enters. When the float doesn’t work well, water keeps coming in, and the tank overflows.

That afternoon, my neighbor went back to his home, but I stayed on the roof. I used to go up there with my dad when I was a kid to study the stars. I contemplated the city. All the rooftops are full of tanks, black and blue, large and small. I told myself that if I didn’t want to have problems with the neighbors, I had to change the float quickly. But, of course, I hadn’t brought that in my suitcase. So the next day, I had to start looking for it.

In Cuba, shortages have become chronic. Therefore, after the exit permit from the country was eliminated in 2013, many people started traveling abroad to import goods. These could range from instant drinks or packs of sanitary pads to hardware or appliances. This is the commercial suitcase. This is how many small private businesses are supplied. On the eighth day after my arrival, I went to one of these places. It wasn’t a store per se but rather a stall on the porch of a house.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Karla]: There, in houses, they sell everything. There are many products, things like hardware, plumbing supplies, batteries, gaskets, the float that they told me costs 3,500; they don’t display the prices. They look at you and tell you the price they think.

3,500 pesos, about 28 dollars. In Lisbon, it would have cost me about 6 euros. Before buying it, I decided to talk to the friend who had helped me with the electricity. I’m not an expert, but I knew that we had changed that float not long ago, so I preferred to make sure that it really needed to be replaced. My friend came home with another friend, they checked everything, and determined that indeed, the float was not working well, but that was not the only issue. The tank installation, done by my father many years ago, already had its little problem, and the tank itself, which was also very old, had a leak that we hadn’t seen.

According to them, the only thing I could do was buy a new tank and redo the entire installation. They didn’t know how to do that. They couldn’t help me. So now I had to find where to buy a new tank and find someone to install it. All of which requires time and money, of course.

That night I had a nightmare. Sometimes I have weird dreams, and when I wake up, I jot down the memories that linger. I wrote that the tank exploded, and the apartment was filling with water. Everyone was at home: my parents, my sister, the friend who lives with us. But I didn’t see anyone; I just heard Dad shouting at me to get on the bed. But the water went on flowing. My room was filling up; the furniture was disappearing. I know someone who interprets dreams, and surely dreaming about water has some interesting meaning. But my dream was very simple: it had to do solely and exclusively with a damn broken tank.

The next day, I woke up before six in the morning with a resolution: I was going to empty the tank and use other reserves we had at home, even if they were smaller. That’s how neighbors without their own tank do it. Ours and its entire installation needed to be renewed, but I wanted to do it right. So I tore a page from my diary and wrote the word “float” as number one on a new list and “renew the entire water installation” as the “theme” for the next trip. I had only been in Havana for a week, and I was already starting to organize my next suitcase.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after the break.

[Daniel]: We’re back on Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Karla Suárez picks up the story.

Just nine days after arriving in Cuba, everything seemed to calm down. I had already decided that the tank would be fixed on my next trip, and after several visits to the telephone company, I finally had a cellphone. What worried me was that the food reserves I had brought in my suitcase were starting to decrease. I had pasta, rice, beans, cheeses, and cans of tuna and sardines, but I didn’t want to be eating only canned goods. Those who live in Cuba have what is known as a “ration book” with which they can buy some basic products at a lower price, but for years, what is sold there is not enough for the month. Besides, I don’t have a ration book. I had to buy from private stores. And this also became an odyssey.

[Karla]: I was at a store just now. I bought a package of chicken of about ten pounds for 3,600 pesos and a small ice cream jar for 350 pesos. There was yogurt for 500 pesos, but I didn’t buy it because I have to go get a carton of eggs, which means 30 eggs that cost me 2,000 pesos. What I brought with me is not enough. Prices have skyrocketed.

In Cuba, there were two currencies, but in 2021 a process was started to unify them into one, the original: the Cuban peso. Since then, prices have increased jaw-droppingly. Before the unification, 1 dollar was equivalent to 24 Cuban pesos. Now it is equivalent to 110 pesos. And that is according to the official exchange rate; the value rises constantly in the informal exchange. I didn’t understand anything. I had only been abroad for almost a year, and the country was different. It’s shocking for a package of ten pounds of chicken to cost 3,600 pesos, about 29 dollars. Similarly, 30 eggs for 16 dollars. A university professor earns about 6,000 pesos a month, which is like 49 dollars. But the price is not the only problem.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Karla]: Today, I went to the bank to withdraw money because I had no money to buy anything. So I went to the bank at 41st and 42nd, and the ATM had no money, just like yesterday. And the day before yesterday.

Withdrawing money also became a complicated adventure. Once, after going to several ATMs, I ended up going into a bank, and after a long line, when I got to the counter, the man told me they only had 10-peso bills. I left there like the robbers in the movies, full of bundles of bills. But as soon as I crossed the street, there was a little vegetable market in front, and all the money disappeared in an instant. Absurd. It’s all too absurd.

One of the things that frustrated me the most about all this was the amount of time I had to invest in seemingly simple activities: going to an ATM, buying from a store. Hours slipped away from me and everyone else while doing almost nothing. At home, they tried to encourage me: “Stay calm,” they said, “you’ll see that everything will work out.”

But it didn’t.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Karla]: It might seem like I’m making things up, but there’s no need. On this island, you don’t need to make things up. The refrigerator just broke. We noticed it in the morning. It spent the whole night like that. It’s on, but it doesn’t freeze, and it barely cools. I don’t know what to do. Cry. I don’t know.

That happened on the 10th day after my arrival. It was as if the city were telling me, “I’m doing this so you don’t forget me, so you have something to tell.” But I chose not to respond.

After a long silence, I grabbed my phone to call the friend who always knows someone handy and ask whether he knew anyone who knew about refrigerators. That night, a neighbor took the chicken packages to store them in her house so they wouldn’t spoil. I bought a beer and went to drink it on the little balcony behind our apartment. From there, you can see the courtyard of the elementary school where I learned to read. As I drank, water started pouring out of a neighbor’s tank, and another neighbor leaned out his window protesting. I raised the beer can to toast in the air.

Between one thing and another, even though the main reason for my trips is always to see my family and friends, by that point, I had only seen my mom, those who passed by my house, and the musicians I went to the concert with in the first few days. With the rest of the people, I had communicated by phone. In Havana, I spend hours on the landline. I have a little address book that I will never throw away. I am sometimes a bit of a fetishist. It’s quite battered. Many of its pages I had to tape at some point, but I prefer to keep it because there are the names of all my people over the years. And there are the crossed-out names. Those who will no longer answer a landline in Havana. On this trip, I had to cross out the name of another friend whom I used to see when I went there, but I already have his new phone number written down, now in the United States.

So I spent the following days visiting my family, aunts, and cousins. And the rest of my friends. They are not numerous, but they are great friends. This time I was lucky to coincide with concerts by several artists I like, such as the troubadour Frank Delgado with whom I am also united by a friendship that goes back many years. I even danced rock at one of those discos frequented by people of my age, former teenagers of the eighties. Sometimes music saves us. Or makes us fly, at least for a while.

We managed to fix the refrigerator when I had only a few days left to return to Europe. Another problem solved. Last Saturday, I was invited to give a talk with young authors at the writing school. And since it’s close to the sea, I agreed with my friends to go swimming later. With so many problems, I hadn’t been able to do it yet, and that’s one of the things I love. I grew up bathing on the coast, which is probably why I prefer rocks to sandy beaches.

As usual, the water was warm and transparent. We could see small fish. Hours later, we watched the sunset with my friends, all of us in the water. I love that time of the day. I dove in, came out, swam, and looking at the horizon, I said goodbye to the sun as it disappeared swallowed by the sea that I love so much.

And the time came to pack for my return. That is much easier. On each trip, I take books from my mom’s library and a bottle of rum, which I wrap in old clothes to prevent it from breaking. There are things I always wanted to leave in Havana because they belong to who I was when I lived there. Certain books and objects. It’s as if, by leaving them in their place, a little piece of me were also staying. My engineering degree, for example, has always been there, but this time I decided to take it with me. I haven’t practiced as an engineer for years, but now I wanted to have it with me.

Once, talking about the Cuban suitcase with my friend Idalmys, she said something that I found very beautiful. She has been living in the Canary Islands for thirty years, and although she could, she hasn’t wanted to return to Cuba.

[Idalmys]: For many years, I lived with things that fit in a suitcase. They wanted to give me things. “Do you want a cutlery set?” Do you want something that sounded like settling down, you know, like putting down roots? And I didn’t want it. I didn’t want anything. Just what fit in a suitcase. And a few years ago, very few, maybe about six years ago, I bought myself an armchair. I bought myself a comfortable armchair, and I wanted to watch TV in a reclining chair with a certain comfort. And buying the chair, I realized that the chair no longer fit in the suitcase, that I was getting a little older, or starting to put down roots, right? And it was the first time in many years that I realized I wanted to settle down with that chair.

[Karla]: Maybe I have also started to put down roots and haven’t even realized it. Twenty-five years is quite a long time, isn’t it? Or maybe it’s just that, as Idalmys says, we are getting older. She and I are almost the same age, and we left around the same time.

My generation experienced the crisis of the nineties in our twenties. Now we are the age our parents were back then, and it’s again a crisis, but even deeper. And people continue to leave, with or without a suitcase. In recent years, the number of Cuban emigrants has been increasing wildly. That leaky faucet can’t be repaired. Entire families are leaving. The children of those who didn’t leave in the nineties are doing it now. And some of those who didn’t leave then are also leaving. On this trip, I found my friends more tired than ever. Fed up with the difficult day-to-day. If I could, I would take some people in my suitcase.

I arrived in Lisbon on a Wednesday. Each return is different. I left the suitcase on the floor of my studio and didn’t even unpack what was inside. It wasn’t much, anyway. For several days, I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I sent messages to my friends here, saying that I had arrived, but that we would see each other later. The truth is I didn’t have much desire to talk about my trip. I needed distance.

Something happened to me in Havana. Since there are transportation problems, I usually walk everywhere. Fortunately, I enjoy walking. One afternoon, I was walking on a tree-lined street and saw a beautiful royal poinciana tree, so I stopped. Since I arrived there, I had been saddened to see so many overflowing garbage bins. My Havana is dirty, and it’s unattractive. But that tree was pure beauty: huge, full of red flowers forming a sort of roof. It seemed so beautiful that I took out my phone and took a picture. A lady passed by me, and without stopping, she commented, “they only want to photograph the garbage bins.” I looked at her, but she had already moved on. Surely, she didn’t like anyone looking at her city with disapproval. But I only stopped to capture the beauty, ma’am; I need it because this city is also mine. Later, I became curious, zoomed in on the photo, and yes, beyond the royal poinciana, at the end of the street, there was an overflowing garbage bin.

For several more days, I continued without touching my suitcase. Until one afternoon, I sat in front of it and stared at it. Sometimes, certain objects seem alive. Before my trip, I asked many people about their Cuban suitcase. Some didn’t want to answer. They said that just thinking about it made them feel overwhelmed or that they preferred not to record their voice because they worried about who might hear them. Those who did agree to answer did so between smiles and pauses of silence. Sitting there, looking at my suitcase, it seemed as if their voices were starting to come out of it:

[Andrea]: I would like to take everything, medical supplies, syringes, needles, and food.

[Guillermo]: Kitchen utensils or faucets. Or a plastic pipe or cables. Hardware stuff.

[Abraham]: A pair of sneakers for school, earplugs for swimming, disposable diapers, baby butt cream… From scrub pads for cleaning to detergent, to toilet paper, to medicines, aspirins. And everything one comes across that you see that you know is not in Cuba, and you feel like putting it in that suitcase.

[Karla]: Listening to those voices in my head, I realized that if I didn’t want to talk to anyone, it was because I had returned with very mixed feelings. A mix of smiles and pauses of silence. Joy for having seen my people and anger, a lot of anger, for the situation they are going through.

In three weeks, I had experienced a bit of everything. Problems and more problems, with or without immediate solutions. A whirlwind, but it was like a dream, like a pause in my everyday life. Then I got on a plane, and slowly the island with its problems was left behind. But so were so many people I love. All of them with their problems. And that is very sad.

Many times I’ve been asked whether I feel guilty for leaving Cuba or for not wanting to return at some point. It’s the eternal guilt that so many emigrants feel. But no, I don’t feel guilty. I would leave a thousand times again, because I don’t want to live in my country, although I also can’t stay away for too long. I can’t, and I don’t want to.

It’s challenging not to be able to see those I love, my parents, my friends, and family. My dear aunt Josefina, whom I hugged on this last trip without knowing that goodbye would be our last because she passed away shortly after my return. And I will return to scatter her ashes at sea, as I did with my father’s. And to continue watching my step-nephews grow before they may also embark on their journey. And to lie down on my bed and imagine that just by doing that, I become who I used to be. And to see the royal poincianas full of flowers. And to carry my suitcase full of things that those who remain may ask for, until all that’s needed are simple tourist suitcases.

It seems that, without realizing it, I have been putting down roots in other places, but there is still one that pulls and pulls and pulls because it is strong and resists. So, thinking about all that while looking at my suitcase, I decided to throw myself on the floor to open it, and finally, I took out what was inside, a few things. In their place, I put the little piece of paper I had written in Havana. On top, it said: 1. Float. Next to it: Renew the entire water installation.

I closed the suitcase, and that’s how my next journey began.

[Daniel]: Karla Suárez is a writer. She lives in Lisbon. Her most recent novel is titled “El hijo del héroe.” This episode was edited by Camila Segura, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Luis Fernando Vargas, and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. The sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with original music by Ana Tuirán.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Adriana Bernal, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo, and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios. It is produced and mixed on Hindenburg PRO.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.