The Day You Are Gone | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

We know that everything eventually ends… happy moments, sad ones, jobs, relationships. Many of us find it difficult to accept this, even though we deal with small or large closures every day.

Of all, the most significant ending for people, the one we find most difficult to face, the one we fear the most, is the end of life. Yes, some say they are not afraid of death, but surely almost no one on the planet would tell you they are not afraid of losing a loved one. It’s a fear we all know.

Today’s story is about this fear. About the efforts we make to overcome it and what it means to accept the inevitable.

After the break, journalist Marisa Candia Cadavid will bring us the story.

[Daniel]: We’re back. This is Marisa:

[Marisa Candia]: Yolanda is the youngest nonagenarian I know.

[Yolanda Lagomarsino]: Well, my name is Yolanda Lagomarsino Rivera. I was born on March 2, 1925 in Chile, and I am Marisita Candia Cadavid’s grandmother.

[Marisa]: My paternal grandmother is 98 years old and has lived in Spain since 1976. She came here with her children fleeing the dictatorship, and most of her grandchildren were born here. She loves to talk about politics and travel, reads Isabel Allende, and dances Chilean cuecas, although there is no swing or reggaeton that she can’t handle also. Few people mean as much to me as she does. She has such an adventurous way of enjoying life that I can’t help but feel inspired watching her. So for a decade I have made it my mission to record her in all sorts of situations.

Cooking…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Yolanda]: Marisita, did you cover the pot well? Hand me the strainer, please.

[Marisa]: Where is the strainer?

[Yolanda]: Over there.

[Marisa]: Dancing…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Marisa]: Go, abuelita! Very nice.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Marisa]: Doing gymnastics…

From here to the Olympics.

[Yolanda]: From here to the Olympics.

[Marisa]: Toasting…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Marisa]: Here’s to my abuelita!

[Yolanda]: Looks like I’m getting a farewell!

[Marisa]: And even singing the Chilean anthem:

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

[Yolanda]: Long live Chile, daaaaamn!

[Marisa]: She is a person who always wants new experiences, even at this stage of her life.

Here I recorded her when she became a member of a public library and encouraged other elderly people to follow her example.

[Yolanda]: Look… did you know that at 95 years old you can still become a member of a library? When you reach my age, the only way to continue traveling is to read. With my books I have been all over the world, I have even been to Macondo. Everything I know, I have learned from books.

[Marisa]: She is a person who still gets excited like a child. I recorded her here at age 88 and, together with my grandfather, who was still alive at the time, when I gave them one of the biggest surprises of their lives…

[Marisa]: Abuelita, grandpa, I have to tell you something. This is for you, abuelita. And this is for you. What does it say?

[Yolanda]: Reservation?

[Marisa]: Reservation.

[Grandpa]: Departure March 16th.

[Yolanda]: Flight Madrid to Sant… to Santia… Nooooo!

[Marisa]: We are going to Chile!

[Yolanda]: To Chile? Marisita, this is too much!

[Grandpa]: Do I have to live until March?

[Marisa]: You have to live until March.

But this story really started to take shape in 2021, before her 96th birthday, when we had this conversation:

And if you could make one wish when you turn 96, what would that be?

[Yolanda]: Wishes? I have many wishes.

[Marisa]: Well, tell me; that’s what we’re here for.

[Yolanda]: There are many wishes. I don’t know, I don’t know… to have… to leave this world peacefully. I love you very much; I am going to leave loving you very much.

[Marisa]: Do you think about death a lot? Because you’ve said…

[Yolanda]: Huh?

[Marisa]: I just asked you what you want and your first wish was to leave peacefully. Do you think about death a lot?

[Yolanda]: Well, the truth is—and I have always said it—I am a coward… I am such a coward. I don’t know where I got that cowardice. So I’m afraid of— and I think everyone is afraid of death; I don’t think I’m alone among millions.

[Marisa]: I don’t doubt it. I am one of those people. But I don’t think so much about my death as I do about the death of my loved ones. Specially my grandmother’s. Sometimes I can’t help imagining when the time comes. I wonder what I will say, what I will do, what will be the first memory that will come to my mind of one of the most important people in my life.

Despite that fear, or rather because of that fear, years ago she began to say goodbye in her own way. She takes advantage of any occasion to remind us that she is living extra time, and little by little she has made sure that everyone in the family knows her recipes so that they will continue preparing them when she is no longer here.

Perhaps it is precisely because of this desire to perpetuate her legacy that I have been recording her for so long. I guess it’s as if I was trying, in some way, to capture her image, her laughter, her voice, to preserve them with me always. I believe that deep down she knows it, and that is why, with infinite patience, she always accepts one more take, one more interview.

My grandmother knows very well what it is like to lose a loved one. She lost her parents when she was very young, she also lost her brother and buried her first child. But it was undoubtedly the loss of her husband, almost ten years ago, that forced her to look at death face to face for the first time. To face the fact that death most likely will not be long in coming for her.

My grandparents had six children. They survived many things, among them the Chilean dictatorship while they were aligned with the left. My grandfather Guillermo was a journalist for a newspaper that was raided and closed after the coup. He left the country just a few months later and went first to Colombia. Then he was followed by my father, who had also just started his career as a journalist. Shortly after, my grandmother, aged 50, went to Spain for the first time. One day in December, along with three of her children, she got on a boat in Valparaiso and traveled for a month until she arrived in Barcelona.

[Marisa]: Do you still remember how you felt that day when you and your three children embarked for Spain?

[Yolanda]: Just picture it! What can you feel? A lot. Leaving your country, first of all, leaving everything behind, a whole life, which is a lot, not knowing what the future was and what awaited us.

[Marisa]: But the future was good to my family. In Spain, my grandmother and her three youngest children were reunited with my aunt Vivianne, the eldest of her daughters, who was the first to arrive in Barcelona. A year later, my father and grandfather also arrived, and with the whole family finally reunited, their new life began. Everyone keeps a warm memory of those first years of exile. In Spain, the dictator Francisco Franco had just died, after almost 40 years as head of state, and there was widespread solidarity for people who came to Barcelona fleeing another dictatorship. Since then, although there is no family celebration in which we do not end up singing the Chilean anthem, my family’s visits to that country have been few. I, for example, got to know the country only in 2013, when I surprised my grandparents. My grandmother had been only once before. The trip helped my grandfather reconnect with his only brother, whom he had not seen for twenty years.

[Guillermo]: A big hug, dear brother. After so many years!

[Francisco]: So many years!

[Guillermo]: I’m glad to see you, and still looking good.

[Marisa]: But that reunion was also a farewell. We didn’t know it at the time, but that would be my grandfather’s last trip. In the end he kept his promise to live until March… he died on the 10th of that month, just one year after returning from Chile. He was 89 years old. He was in a hospital room for palliative care. More than sixty years had passed since he and my grandmother met playing basketball.

The day my grandfather died, I found her crying in the hallway. “I’m next,” she said.

[Yolanda]: I always thought that I was going to die first because I always had colds, I was often sick, here and there. On the other hand, I never saw Guillermo sick, ever. You see, here I am and it’s been ten years since he passed away.

[Marisa]: From that day on, something changed in my grandmother: she began to develop a strong fear of dying. It was a night panic. When the day ended and visitors said goodbye, her mind focused on death. Then, alone in bed, she felt her heart rate accelerate and her blood pressure skyrocket.

[Marisa]: When you had those panic attacks at night, do you remember what you thought?

[Yolanda]: No, nothing! That I was going to die, nothing else! The panic attack meant I was going to die and I didn’t want to die. But, well, I woke up the next day and I felt perfect. I said, “Well, the fear is over…”

[Marisa]: And for my grandmother, death is the end. Like many in my family, she is not a believer. And, of course, how can we not fear a void?

But that fear of death, although it was accentuated after my grandfather’s death, has always been present in my grandmother. Any cold, any headache is, in her imagination, a symptom of a serious illness. Everyone in the family has had to get used to dealing with her hypochondria. But if there is one person who has experienced it closely, that is my aunt Vivianne. Since she works in a hospital as a laboratory technician, she is the one my abuelita turns to every time she suffers from what she thinks is a lethal symptom. Besides, of all of them she is the one who lives closest to my abuelita, in the same building. This is Vivianne:

[Vivianne]: Only the elevator separates us. I see my mother every day. When I come home from the lab, and when she goes to bed at night.

[Marisa]: Those night visits, which used to be quick and almost like a formality, began to lengthen since the death of my grandfather Guillermo.

[Vivianne]: She would always ask, “Are you leaving? Are you staying?” In other words, her concern was being alone. I said, “But mom, I’m next door. If you need me, call me. Because I gave—we gave her a buzzer which she could ring in case of an emergency. It is connected here at home so all she had to do was to press the buzzer and I would go.

[Marisa]: Although having the buzzer gave her some security, she began to need company often at night.

[Vivianne]: My sister Carmen came to accompany her to sleep. She stayed with her for quite a while because my mother was terrified of sleeping alone. She was very afraid because she thought that since my father had died, she had to die too.

[Marisa]: My grandmother’s fear increased, of course, when the fragility of her body betrayed her. In August 2022, she was in the hospital for a blood infection. She returned home after twenty days. Physically, she recovered, but her spirit was not the same.

[Vivianne]: She said no, that it was time for us to leave her alone… Because. And I said, “No, mom, come on, let’s see…” Of course, then we laughed because she said, “You don’t even let me be old! I’m 98 years old!”

[Marisa]: And she is right. I don’t know whether we do it for her sake, or for our own selfishness, but it’s hard for everyone in the family to admit that my grandmother is almost 100 years old.

[Vivianne]: She is 98 years old, but to me she is not old. All day long she talks to you about projects, “And we could do this and we could do that…” She even talks to you about starting businesses…

[Marisa]: All the time.

[Vivianne]: All the time. So, you say, “Well, at 98 years old, if she is full of life, what do we do? Imitate her.”

[Marisa]: Imitate her. Still, just in case, my grandmother—always with death on her mind—has developed a ritual with my aunt Vivianne.

[Vivianne]: We say goodbye every night, and she says, “So, if I’m alive tomorrow…” I tell her, “Well, if you are going to die tonight, let’s say goodbye, then.” “Okay,” she says, “let’s say goodbye.” “Okay, mom. Everything has been a delight.” “Okay, okay, okay.” “Good night.” “Good night.” The next day I call her because, of course, you also have those thoughts, “Let’s see whether she really has died,” and when she picks up the phone, I say, “Ah, so you are still alive? You haven’t died?” “No, no,” she says, “I’m going to keep nagging.” And I say, “Okay, fine.”

[Marisa]: I wanted to accompany my grandmother in that anxiety, and the reality is that neither my aunt, nor I, nor anyone in my family, has the appropriate training to provide the support my grandmother needs in this final phase of her life. That’s why I decided to go to an expert.

[Marian García]: Dying is not easy, let’s not kid ourselves. I… I tend to make light of death; I tend to even laugh.

[Marisa]: She is Marian García, a retired nurse who for a decade accompanied different people on their way to death. She says the time she spent working in palliative care was the best of her professional life.

[Marian]: Working with death and with people who are close to death gives you a different quality and warmth. People who are about to die, whether they know it or not—because deep down everyone knows it—they no longer care about nonsense; they care for what is authentic. That authenticity is priceless because it helps you understand that there are things that are essential and things that are not. It helps you tie up your loose ends, keep your checking account up to date, without red numbers.

[Marisa]: Now Marian tries to live this way, applying those teachings in her daily life. She claims that every person she has helped die has taught her how to live. But I wanted to ask her directly: How do you talk about death with a person who knows they have little time left to live?

[Marian]: There is a maxim in palliative care, and it is that the patient has to know everything he or she wants to know, and only what he or she wants to know. Never lie to a patient. Be quiet; silence is better than a lie. You cannot tell him or her, “You are not going to die,” or, “You are going to die tomorrow.” Neither of those things is true—you don’t know. Ask! “How do you think you are?” “What do you think?” “What do you feel?” “What does your body tell you?” “What do you think?” “What do you fantasize about?” Because that person is going to tell you—just give them the space to speak. Accompany him or her in that communication.

[Marisa]: And it is precisely this support that is the most difficult to achieve. It is difficult for us to listen to the doubts, the fears, the uncertainty expressed by someone who has reached their final phase. According to Marian, it is a natural fear that we all share.

[Marian]: That fear of, “I’m here for whatever you tell me.” If you tell me, “I’m dying,” I accept it. If you tell me, “I don’t want to die,” I accept that too, and if you ask me, I will tell you: “I don’t know when you are going to die, but I will be here with you.”

[Marisa]: And most importantly, death is the most natural thing in life. And just as with everyday things, there is room for fun.

[Marian]: And you laugh with them, because there is nothing gloomy or morbid in palliative care, no way! … At least I haven’t experienced it like that. There is a lot of sense of humor, from the patients themselves, and I have allowed myself, of course, when the time was right and when it was appropriate, to laugh out loud with them. I have also cried, but I have laughed with them.

[Marisa]: I wanted to follow Marian’s advice and be there for my grandmother. So on a hot summer day in 2023, I gathered my courage and headed to her house.

[Marisa]: Hello.

[Yolanda]: Hello.

[Marisa]: Hello, grandma.

[Yolanda]: Hello, mijita, how are you?

[Marisa]: Very good.

[Yolanda]: Come in.

[Marisa]: May I?

[Yolanda]: Yes! Come.

[Marisa]: I began by asking her about her first experience with death. Her mother’s, when she was 9 years old.

[Yolanda]: For me it was… it was a very big shock when my mother died because my mother died during childbirth, she died young and we were four siblings, and I was 9 years old when she died. And it was so, so sudden, because I see her leaving, we heard her leave at 6 in the morning to have her child, and by 10 o’clock that morning she had died. And it was a very big shock, because I thought that when my mother died the world was not going to be a world anymore, it was not going to work.

[Marisa]: The world went on, but the real possibility of leaving this life without warning—and as suddenly as it happened to her mother—created a very big fear in my grandmother. That’s why, that June afternoon, I was willing to help her face that fear even if it meant having a conversation that neither she nor I wanted to have.

Why do you think it is so difficult for us to talk about death?

[Yolanda]: Because we don’t want it, and I say this from experience, because as the years go by, we want to die less and less.

[Marisa]: And what is it that scares you about death, abuelita?

[Yolanda]: The truth is that I couldn’t really define it.

[Marisa]: She says she can’t define it, but I think it’s clear. My grandmother is always the first one to sign up for any outing, trip or family plan. The idea that, all of a sudden, she might no longer go on enjoying life is inconceivable to her. That’s why she didn’t surprise me when she answered my next question without a moment’s hesitation:

[Marisa]: Tell me something you would definitely like to do before you leave.

[Yolanda]: Well! I would like to do so many things! I would like to do… oh, I don’t know. I would like to move again, as I used to when I had a business, when I worked… to do things again, because now doing nothing is also something that stresses you out a lot.

[Marisa]: The conversation was progressing well, but I couldn’t help feeling some apprehension inside. I was very aware that I was forcing a talk that my grandmother had not asked for. But I felt like there was no turning back. I was willing to continue insisting, convinced that my grandmother would thank me one day. But then, the conversation that up until that moment had been so difficult took an unexpected turn:

[Marisa]: And what happens then, after death? Is there anything?

[Yolanda]: I think not. You die, and you die, and you don’t come back.

[Marisa]: So, when you die, you’re not going to come see me in my dreams or talk to me?

[Yolanda]: No, you’re going to dream about me! That will happen, but I’m not going to get involved; I’m not going to get involved telling you: “Hey, I’m having a good time here in this world.”

[Yolanda]: Or “I’m having a bad time,” no.

[Marisa]: And so, after a difficult start, we were both laughing openly, while we imagined what life would be like without her. Then I understood what Marian explained to me about having a sense of humor in palliative care. And because the atmosphere was a little more relaxed, and she was opening up, I went ahead and asked her:

Are you ready to die?

[Yolanda]: Ready—well, I think that at 98 years old, I do believe that everyone is ready to die at 98 years old, eh? Now, whether I want it to come is another thing.

[Marisa]: I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. The same person who not so long ago had suffered panic attacks because of her fear of death was now telling me that she was ready to die.

[Marisa]: I hope it doesn’t happen, but if you died tomorrow, for example, or today, would you go away peacefully and satisfied with the life you’ve had?

[Yolanda]: Look, I would leave calm and happy, because I have received all the love and attention from my entire family, from all my children… my children, my grandsons and my granddaughters.

[Marisa]: And then I realized something. In the same way my grandmother took care of me as a child, she was taking care of me now. Because I was the one who really needed comfort.

There is one thing that I have never told you: that you fear death and I… I do not fear my death, but I do fear your death. Because the day you die, wow… it’s going to be very hard.

[Yolanda]: What are you saying! What are you saying, darling! You have to accept it.

[Marisa]: Yes, but… of course, you will die and not notice it, but the rest of us who will be there crying for you…

[Yolanda]: But of course, darling, there is a thing called time. Time levels and balances all things.

[Marisa]: Do you think it will be a matter of time?

[Yolanda]: Just imagine! We overcame death, I overcame my mother’s death, then my father’s death, then my son’s. I was 25 years old and my son died when he was eight months old. And for me it was a terrible thing, it was a dreadful thing. But look, over time that pain has faded, although it is always in my heart.

[Marisa]: I was slowly realizing that my questions were nothing more than a desperate attempt to find some common ground, an answer that would give me relief when she was gone. And then this happened:

[Yolanda]: Well, darling. Why are we talking about death?

[Marisa]: Because I think it’s important, abuelita. It worries me.

[Yolanda]: Well, then, darling, who is more obsessed with death? You or I?

[Marisa]: Then it became evident to both of us. I was the one who really needed help to face my fear of losing her. And my grandmother, of course, would help me.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[Daniel]: We are back with Radio Ambulante. Marisa Candia Cadavid continues the story.

[Marisa]: Like countless times before, my grandmother was willing to take care of me. Even when we were talking about one of our biggest fears, she put me first. Now it was a matter of finding ways for her to help me. Something came to mind that I had been thinking about since our first conversation about death, although at that time it had a very different purpose. It was going to a very particular activity and, well, you could say that it was not very popular…

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

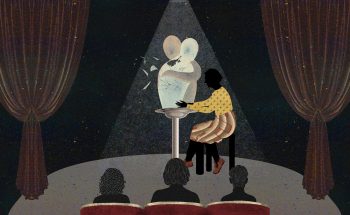

[Marisa]: What you hear is a Death Café, or in Spanish: a Café Muerte. As the name suggests, it is a meeting, usually in a coffee shop, to talk about the end of life.

[Rocío Saiz García-Delgado]: Let’s start by closing our eyes, taking a few breaths to leave the previous life outside, and be centered where we are now, in the Death Café.

[Marisa]: Anyone can participate, from the terminally ill, to people grieving the loss of a loved one, to professionals working on related issues. You don’t have to pay anything, just the coffee you want to drink. The only requirements are: keep an open mind, listen to others, and do not judge. This is explained by Rocío Saiz García-Delgado, who will lead this meeting.

[Rocío]: People can speak, they can refrain from speaking, there can be silence; the times of silence are because from there many more reflections can arise, and ultimately, this is about sharing, listening and enjoying life.

[Marisa]: The first was held in London, in 2011, by a British man named John Underwood and his mother, Sue Barsky Reid. John was working as head of strategy and business development for the council of a London borough, when he came across the work of Bernard Crettaz, a Swiss sociologist who had founded something called Café Mortel. Inspired by that idea, John quit his job to try to establish something similar in London. The goal was to create a comfortable and safe place to talk about death. John’s mother, who is a psychotherapist, developed the methodology, and together they created a guide to follow at each Death Café. They determined that anyone could organize their own, as long as they agreed to follow the guide they had developed and respect its principles.

Now there are Death Cafés in 85 different countries, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, passing through Israel, the United States, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Brazil and Uruguay. The one you are going to hear takes place in a coffee shop in downtown Palma de Mallorca.

[Rocío]: First, we will go around introducing ourselves, and those of us who have been here before will discuss what attracts us and what makes us come to the Death Café. Those here for the first time can say in a few words what has brought you here.

[Marisa]: Rocío is part of Palma Compasiva, the organization that promotes this Death Café. I reached them through an article I found in a local newspaper. It’s the second time I come. And my grandmother Yolanda came with me. I had originally thought of this event as a space for her to release her fears and find comfort. Now, I was the one going for that purpose.

[Yolanda]: Is it just us women who dare to talk about death? Where are the men?

[Marisa]: There are eleven women here, and two men, almost all of us strangers. We sit in a circle. We start by introducing ourselves:

[Carmiña]: Well, my name is Carmiña.

[Ruth]: I’m Ruth.

[Celia]: I am Celia.

[Marisa]: There was also Marian, the palliative care nurse I interviewed, and me, of course….

[Marisa]: I am Marisa.

And even my uncle Pancho, who had come from Holland to spend a few days with his mother and took this opportunity to accompany the two of us.

Thirteen people with thirteen different reasons for being there. Like Carmen:

[Carmen]: Good afternoon, everyone. I am in the middle of mourning for my father and my mother. They both died within six months. I’m sure I’m going to cry, I’m warning you.

[Marisa]: Lapo.

[Lapo]: Death has intruded several times. It has come close to me, and it is interesting to keep it in mind, to know it, and speak openly.

[Marisa]: Or Ana:

[Ana]: My name is Ana. This is not the first time I’ve come. I came because of the need to talk, and since I started talking here, with like-minded people who are open and have experiences, sometimes very sad ones, sometimes wonderful, sometimes both… I have become fond of it.

[Marisa]: My grandmother thought that meeting to talk about death was a waste of time, so she accompanied me with the mission of convincing us all that it would be better for us to talk about life. In some ways, this meeting was going to be a continuation of the conversation we had had at her house just a couple of weeks earlier.

[Yolanda]: My name is Yolanda. I am 98 years old. I think I am the one closest to death. But I am very optimistic. I think we all have to celebrate life because life is a gift.

[Marisa]: Rocío finished the round of introductions:

[Rocío]: And that’s it. From now on, whoever wants to speak, go ahead and speak and comment.

[Marisa]: And we did just that. It was a long and strangely intimate conversation between a group of people, some who had already met a couple of times and others who had literally just met. My grandmother was one of the first to speak:

[Yolanda]: Do you believe in destiny? I do. You are destined to die on such a date, and on such a date you are going to die. Nor before, not after.

[Marisa]: One of the attendees, named Carmen, answered her:

[Carmen]: I don’t know whether I believe in destiny or I don’t, but this concept is helping me. Thinking that my mother had to leave that day, that it was her time. Why are we born on a certain date? Because we have completed a cycle otherwise, I don’t understand why she left.

[Marisa]: It had only been a month since Carmen had lost her mother and six months since she had said goodbye to her father, when she participated in this Death Café. Of all of us who met at that meeting, she was the only one who was in the grieving process. That’s why her words touched us all.

[Carmen]: She caught COVID, and within 24 hours she was gone. My mother was fine, she had nothing… My father, on the other hand, was sick for a year; we said goodbye, we had those conversations where you say, “His death was very beautiful.”

[Marisa]: I admit that I also fantasize about a beautiful death for my grandmother. I would love for her to leave peacefully, in her house and surrounded by her family. But how to prepare for that moment? I was hoping my Death Café friends could help me.

[Marisa]: A very curious thing happened to me that I wanted to share here. In December, November-December 2021, I came looking for ways to help my grandmother because she was having panic attacks because she didn’t want to die; and yet, I have realized throughout this voyage that I am not prepared for her to… well, to say goodbye. I know that we have to go through this, and it is a grief we have to face, but I don’t know whether you have any tools, any advice…

Then there was a silence that was only broken by my grandmother with the same attitude that had surprised me only a couple of weeks before:

[Yolanda]: Let’s not be sad!

[Marisa]: But it was Celia, another of the participants, who offered me the advice I had come looking for:

[Celia]: It is not sadness. What I thought while listening to you is that the experience I have had, living very close to very loved ones, is as if while they are present in this life the whole being is concentrated in one spot. Let’s say, in the body, let’s say, and when they are born again—for me, death is a birth—that closed space opens up and presence expands. Of course, that does not take away the absence, a little of the nostalgia, being able to hug, not being able to laugh with that person; but cultivating or enjoying that presence that is such a gift, or so enveloping, let’s say, and so loving—it is not sad.

[Marisa]: If one thing became very clear to me at this meeting, it is that the experience of the death of a loved one can be very different depending on the way you handle it.

[Rocío]: What you have said about normalizing and talking has brought to mind what I have said so many times about when my mother died.

[Marisa]: The person speaking is Rocío. She is about to explain the traumatic experience she had as a result of the way her family handled the death of her mother.

[Rocío]: There was what is called a pact of silence. My mother, who died within 40 days, was not told, and no one tried to tell her what she had, nor did they tell her six children. And that is what I have experienced, that pact of silence and that pain of not being able to speak, of not being able to say goodbye as I should have, of not having those conversations that we could have had. My mother had to ask her friends, “Am I dying?” And they tried to deceive her when you know that she is dying—of course you know.

[Marisa]: The very idea of keeping such important information from someone who is about to die seemed so surprising to me that I wanted to know more. Later I would investigate and realize that Rocío was right. According to the Spanish Society of Palliative Care, the pact of silence is a fairly common practice. The intention of the family members is usually good, of course. They want to spare the patient more suffering and prevent them from losing hope so they can continue fighting. But all the expert testimonies I found agree that, in the end, all they achieve is denying the patient and their families the possibility of saying goodbye and getting used to the idea of what is about to come. For this reason, Rocío believes that we have to talk about it head-on, when it comes up:

[Rocío]: Naturally, without a lot of fuss, to demystify and talk about those fears and doubts and to say, “Oh, but I love you very much,” or “What you have taught me,” or “If I leave one day, I want you to know that…” or… I don’t know, it is something so, so important, and it would have helped me to have had those conversations with my mother.

[Marisa]: The Death Café conversation ranged far and wide. We talked about fate, grief, euthanasia, how expensive it is to bury someone, and about unwanted loneliness—a matter my grandmother had something to say about.

[Yolanda]: Older people have a very bad time. A phone call makes you feel better. Now, if you are alone all day, not thinking about anything… I wouldn’t know because I have always been surrounded by my children or my granddaughters.

[Marisa]: Well, next month she’s going on a cruise. She hasn’t said it, but…

[Yolanda]: Well, my daughters are taking me on a cruise. I think as a farewell to life (laughs).

[Marisa]: I was sitting there, listening to her and watching the others enjoy and laugh with her, and I felt immense pride in being her granddaughter. I could have continued like that, seeing her close-up, for much longer, but after two hours of conversation, Rocío announced that the Death Café was coming to an end.

[Rocío]: Now it is time to close. Also let’s do another round, this time in the opposite direction, to say, in a few words, what we are taking with us, what we are leaving behind, or how we feel now, at least in one or two words.

[Marisa]: And just like that, one by one, we said goodbye. My grandmother was one of the first:

[Yolanda]: I am very happy, first of all, to have met you all. And, well, what can I say? I have one foot here and the other there, but I am still here and I want to thank you for inviting me to this beautiful session, for having met you and for having listened to each one of the opinions, which I find very valuable.

[Marisa]: At her farewell, Carmen spoke to my grandmother:

[Carmen]: And delighted to have met you. Right now, you have both feet here, so enjoy everything you have left, and it has been a pleasure, I loved it and it has helped me a lot.

[Marisa]: Ana too:

[Ana]: Yolanda, you still have both feet here. I think I have understood that what you have is not exactly fear of death, but the wish to continue being here. And I love it and I hope, if I reach your age, that I look so good.

[Marisa]: And Carmiña…

[Carmiña]: Well, as always, I leave full. I have laughed, I have sung, I have almost cried, my hands were shaking.

Abuelita, you are a light. I hope to see you here again.

[Marisa]: And I spoke, too.

I leave in peace, because what I have experienced here gives me strength to continue and to move forward with my grandmother. I leave happy and full of love.

At the end, Rocío closed the meeting:

[Rocío]: Thank you for coming. Thank you, Abuelita, because I have also adopted you. I adopt grandmothers and mothers (laughs).

[Marisa]: Describing what you feel after going through a Death Café meeting is difficult. The level of intimacy that is achieved is inexplicable. For me, it is as if a bunch of strangers who were initially drifting had ended up rowing together.

I feel that the journey I undertook—at first to help my grandmother overcome her fear of dying, and then mine—is approaching its end. But I can’t finish preparing to face her death without first thinking about what her farewell will be like. The experience with my grandfather Guillermo is still very recent. The procedures with the funeral home are always difficult, but in our case they were more difficult because absolutely nothing had been planned. In just over half an hour we had to decide how and when to say goodbye to someone who had been with us for a lifetime.

My grandfather was an atheist, so we were clear about only two things: we did not want religious symbols on his coffin or a Catholic rite at his farewell. This, in a country with a strong Catholic tradition like Spain, is very difficult to find. In the end we had to accept the coffin with the crucifix because there was no other option. But we passed up the Catholic funeral, the only one they offered us, and instead, we said goodbye to my grandfather one warm afternoon at the end of winter, in a very unconventional ceremony. We listened to music, ate, drank and talked.

I would love for my grandmother’s farewell to be the same. And if I have learned anything from doing this story, it is that you should not leave things undone.

(ARCHIVE SOUNDBITE)

So I returned one last time to her house. And, like all our important meetings, sitting around two cups of tea and some cakes, we recorded the final interview in this story:

[Marisa]: How would you like us to remember you when you are gone?

[Yolanda]: Oh, Marisita! That is asking… how can I know what those who are still alive think of me? Maybe they’ll say, “This old woman, thank goodness she is dead.”

[Marisa]: All right, but if you could choose, how would you like us to remember you?

[Yolanda]: Well, for you to remember me the way I was, really, no more no less.

[Marisa]: If my grandmother wants us to remember her as she is, I imagine she would also want a farewell that befits her. But I wanted to be sure, so I asked her directly.

Have you ever thought about how you would like us to say goodbye to you the day you are no longer here?

[Yolanda]: Well, yes, these are uncomfortable questions, right? Because, of course, one cannot say, “I want this, I want that,” regarding death.

[Marisa]: But anyway, I sensed that what she was not going to want were established formulas or the traditional religious ceremony.

[Yolanda]: No masses but… They will probably go to the funeral home, I don’t know, a funeral home and cremation, and that’s it.

[Marisa]: And that’s it. My grandmother, who never missed a good party, was now reluctant to organize her own. So I had to insist:

Can you imagine, then, a happier farewell perhaps?

[Yolanda]: Yes, that’s it. A happy farewell, a farewell with… I don’t know, not a lot of crying or drama, right? Because in the end, we all have to leave this world one day, and my time has come… and that’s it.

[Marisa]: That’s it. Again. I could tell that my grandmother was starting to get tired of my insistence, but, just as Marian had taught me, I wanted to close our pending issues. Making sure that the day she is gone, I will have told her everything I felt. It is impossible to guess what our last words will be, our last kiss, our last caress with a loved one. But if life, destiny or a divine presence—call it whatever you want—prevents me from having one last conversation with her, at least I will always have this one:

[Marisa]: I would like us to do an exercise. Imagine this is the last conversation we are ever going to have. What would you like to say to me?

[Yolanda]: What do you want me to say? You were my first granddaughter. Having your first grandchild is like returning to your youth, like having your first child again. I think I wish you the greatest happiness in the world and may you live many years.

[Marisa]: Now I’m going to start crying. I… if this were the last time I spoke to you, I would thank you for everything you have done for me…

[Yolanda]: What have I done, darling? I did not do anything!

[Marisa]: You have taken care of me since I was a child, always, and not only that. And all the times you’ve put up with me, that I’ve put a microphone in front of you, that I’ve forced you to act, that I’ve forced you to look at the camera…

[Yolanda]: But I loved it! Imagine feeling like I’m working on the radio again.

[Marisa]: Well, let me finish. I want you to know that I love you very much, that you are the best grandmother that could happen to me in the world, the best grandmother in the world. And that I will never, never, never, never forget you.

[Yolanda]: I hope so, darling.

[Marisa]: I will continue making your potato salad, all the recipes you have taught me to make…. Every time I dance a cueca, a reggaeton, a tango, a swing…

[Yolanda]: That’s what I want, that when I’m gone everyone dances and everyone laughs as we always have.

[Marisa]: We will do it. I love you very much, abuelita.

[Yolanda]: All right, thank you, darling.

[Daniel]: Yolanda went on her Mediterranean cruise between July 21 and 28, 2023. She continues to live in Palma de Mallorca, enjoying life and starting to plan her 100th birthday party. Her granddaughter Marisa is helping her. The two still keep their regular dates with tea and cakes.

Death Cafés continue to be held regularly in many countries. On their official website, deathcafe.com, you can check where and when the next one will meet.

Marisa Candia Cadavid is a journalist and lives in Palma de Mallorca. She co-produced this story with David Trujillo, our senior producer. Editing was done by Camila Segura and Luis Fernando Vargas. Bruno Scelza did the fact checking. The sound design and music is by Andrés Azpiri.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Rémy Lozano, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Natalia Ramírez, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill, Ana Tuírán and Elsa Liliana Ulloa.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.