The Memory Keeper | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Lupa is our new app for Spanish learners who want to study with Radio Ambulante’s stories. More info at Lupa.app.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Hay Festival Pre-Roll]

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

One afternoon in 1977, when this story begins, Inés Gaona was carrying her baby in her arms. It was the final days of July, and that winter in Paraná, the capital of the province of Entre Ríos, in Argentina, had not been so harsh as others. Inés tucked in her baby, barely 5 days old, and walked to the house of her mother-in-law, Ederlinda.

She was going to introduce her daughter Evangelina. Inés was married to Ederlinda’s youngest son, Blas Jaime. They had met when she was 16 years old and he was working as a clerk in a publishing house. And even now, although they had been married for more than 17 years and had a teenage son, there were still many things that Inés did not understand about her husband’s family. One of them especially intrigued her: when her mother-in-law came to visit, Inés used to hear her and Blas conversing in a language that she did not understand and that was unlike any she had ever heard.

They spoke softly, as if they didn’t want to be heard…

[Inés Gaona]: And from time to time, I would hear a strange tongue, and when I approached, they would change the conversation.

[Daniel]: They immediately stopped speaking in that other language. One day, Inés was encouraged to ask her mother-in-law what language that was. Blas had never made it clear to her. But Ederlinda avoided answering. She said only, “You’ll find out.” That time, she had preferred not to insist. She didn’t want to be nosy and, besides, she really liked the relationship she had with her—talking with that mysterious woman that everyone in the neighborhood called “Morocha” because of her dark hair and skin. Inés, on the other hand, was a typical daughter of German immigrants, with blonde, almost white hair.

And even though there were parts of Morocha’s life that she couldn’t access, she was fascinated by her strong character, even though she had never heard her raise her voice. And that she didn’t laugh much, but she always had a half smile on her face.

Morocha, moreover, had always treated her like a daughter.

[Inés]: She always said, “You are the daughter that I do not have.” And I said jokingly, “But I’m white and blonde and you’re dark.” “Well, but you’re still my daughter because we’re all the same; the color doesn’t matter.”

[Daniel]: For this reason, that afternoon when she went to introduce her 5-day-old baby, when Morocha asked to be alone with the child for a while, Inés did not hesitate. She approached her mother-in-law and carefully handed her the baby to tuck her in. With the baby in her arms, Morocha walked to her bedroom, went in, and closed the door.

Inés trusted her, but at the same time she wanted to know what was happening, so without making any noise, she followed her and stopped in front of the door. It was closed, but she could see through a small glass.

[Inés]: And I spied on her there, and the first thing she did was she took out a small mirror, she opened her mouth, she looked at her palate.

[Daniel]: As if she was looking for something.

[Inés]: Then she took off the baby’s diaper and put her hand on her head.

[Daniel]: Leaning on the door, Inés listened as Morocha whispered to her granddaughter a few words in that language that she still didn’t know. It was only a few minutes. Afterwards, she dressed the baby again and came out of the room.

[Inés]: She tells me, “Okay, that’s it.”

[Daniel]: Inés took her daughter in her arms and didn’t say anything more. She was intrigued, but then again, she felt that asking about what she had just seen might seem like a lack of trust in her mother-in-law. And she didn’t want to offend her. She also did not discuss it with her husband when she saw him. But she couldn’t get what she had witnessed out of her head, so a few days later she decided to ask:

[Inés]: Grandma, what did you do to Evangelina when I brought her to you?

“No…” she said. “I saw that she has a cross on her palate and a cross on her tummy. That is the sign.”

[Daniel]: Inés did not understand. A sign of what?

That she was a real Chaná, her mother-in-law told her. And she added:

[Inés]: And if she’s the last one, she’s going to be the memory keeper.

[Daniel]: “The memory keeper…” Inés did not understand what that meant. But that other word, Chaná—she had heard it often in recent years.

[Inés]: But when she said Chaná, I said, “Why do you say that?” Because I didn’t know anything about them, and I did not know they existed.

[Daniel]: This time, Inés didn’t keep asking questions, and her mother-in-law did not explain much more. The family was like that, not very chatty. She did not tell her that she, her son Blas, and now her granddaughter Evangelina were part of an indigenous lineage that had inhabited those lands for centuries—the Chaná—long before the arrival of the Spanish colonizers. And that, at the beginning of the 19th century, they had been persecuted and impoverished until they almost disappeared.

Neither did she tell her that they, the women of her family, had transmitted the culture of that almost extinct tribe by word of mouth from generation to generation. And likewise, their language, that secret language, that “strange tongue” that Inés did not understand and that had been lost to the world for almost two centuries.

And there was something else that Morocha did not tell Inés that day. The most important thing of all: that Evangelina, her five-day-old daughter, was the one chosen so that the Chaná language, that almost dead language, would one day come back to exist in this world.

We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Emilia Erbetta picks up the story.

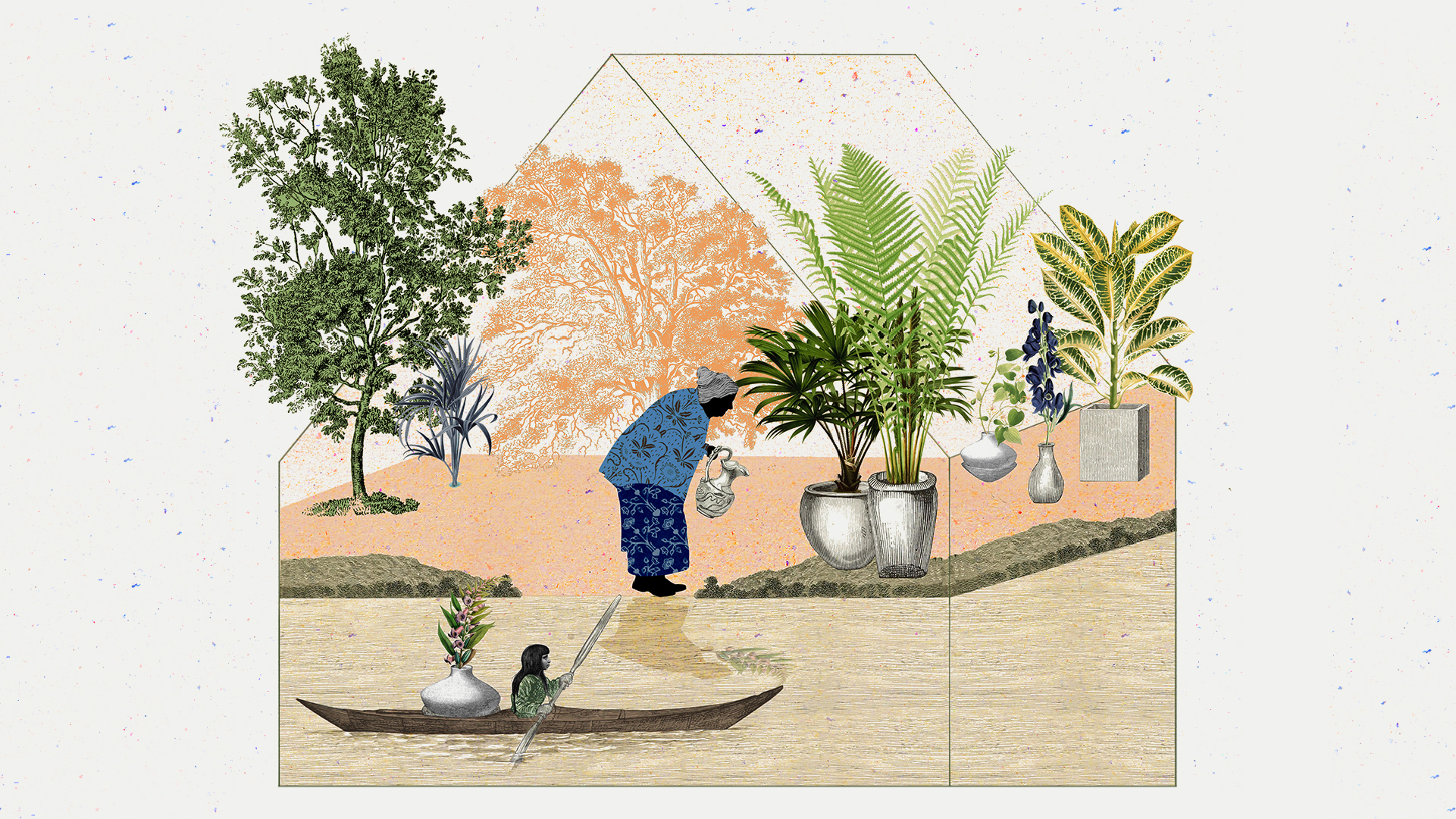

[Emilia Erbetta]: Growing up, Evangelina always felt a special affinity for Morocha. Like her mother, Inés, she was fascinated by the world of her grandmother, and she loved to go whenever the family visited. From a very young age, she had noticed that she was different from the women of German descent on her mother’s side, who always told her to come inside the house to get away from the bugs and get shelter from the sun’s rays. But Morocha didn’t do that. She liked to go out with her granddaughter to her garden, throw herself under the trees and eat oranges with the sun hitting their faces.

[Emilia]: From the outside, Morocha’s house was the same as any other in Paraná, a rather small city for a provincial capital. But when the little gate that led to the house opened, Evangelina was amazed.

[Evangelina]: It was like entering a forest… because there were trees and plants everywhere.

[Emilia]: They grew all over the house: in pots, in the ground, in cans. Evangelina remembers her grandmother almost always in the same position. If she closes her eyes she can still see her:

[Evangelina]: Crouched down. Always among the plants. Always picking something out or pouring water on them or watering them…

[Emilia]: There was also a large anacahuita, a tree that was sacred to her grandmother. In the spring it was full of white flowers, and it produced round, yellow fruits, and with its leaves Morocha prepared a tea to relieve coughs and colds.

Each little herb, Morocha explained to her granddaughter, had a special function, and many of the ones that grew in her garden were used to heal. Some were for stomachaches or headaches. Others to relieve the eyes.

Morocha had learned all that from her mother, and her mother had learned it from hers. It was knowledge passed down for centuries, by men and women who paddled upriver in canoes made of sticks and mats. They built their villages on large mounds of earth, bone and ceramics, to protect themselves from the flooding of the river. They lived by hunting, fishing and gathering fruit. They made clay pieces in animal shapes. And for more than 2,000 years, they were born and died on those same lands where Morocha now grew her plants under the fascinated gaze of her granddaughter.

Chaná men and women. Just like them.

During the first years of her life, Evangelina gradually absorbed the history of her ancestors. She was five or six years old when, on warm summer nights, she would sit under the table and learn things the way all children do: by listening to the adults talking. And although she was too young to understand what her grandmother and her father were talking about, she clearly remembers something that Morocha repeated to her:

[Evangelina]: “We are different.” But I thought that was because my grandmother loved me more than my other cousins, her other grandchildren.

[Emilia]: But sometimes, they also mentioned that other word to her:

[Evangelina]: We are Chaná. Our family is Chaná.

[Emilia]: Evangelina did not understand what Morocha meant by being Chaná or being different from the rest. And she didn’t find many explanations elsewhere either. Her father, Blas, rarely talked about it, and her mother, Inés, like her, didn’t know much about it either. But there was one thing that Evangelina was clear about from a young age: Part of being a Chaná involved learning to endure pain. Her grandmother always told her so.

[Evangelina]: A Chaná does not cry; a Chaná is proud. He is a warrior, he is strong, so he cannot cry…

[Emilia]: Morocha had also learned this as a child, and among the Chaná it had always been like this. A crying baby could alert the enemy or reveal where a camp was being set up. And besides, they considered it a sign of weakness.

So, without completely realizing it, Evangelina was learning to understand life that way.

[Evangelina]: Then there came a time when I would hurt myself, I would fall, or cut myself, and I didn’t cry. I got up, shook myself off, and kept going.

[Emilia]: Between the German customs of her maternal family and the Chaná customs of her father and grandmother, Evangelina spent her entire childhood without experiencing any conflict between those two ways of being in the world. It was as if she had two halves and there was nothing strange about that.

However, a large part of that Chaná half went with her grandmother Morocha, who died when she was 11 years old, one November day in 1988. Her death left Evangelina feeling puzzled, as if none of it was entirely real.

[Evangelina]: I went to the wake and everything, but it was like seeing it in a dream, like I was on a cloud and it was there. And when Sunday came, where do I go? Because I used to go to my grandmother’s house; we always went. Then it was like a void that left me spinning.

[Emilia]: During those years they shared together, her grandmother had taught her many things with few words. Among them, the value of silence: Morocha mentioned the Chaná only within the family, with extremely trusted people, and Evangelina had learned that lesson:

[Evangelina]: It stayed in there. I mean, even though I was a child, I was not going around saying, “I am Chaná, I am Chaná…” no.

[Emilia]: Although, actually, nobody outside her home talked about them either. Evangelina realized this at school. It was as if the Chaná people were some kind of legend in her family. In elementary school, no teacher ever mentioned them. There were no classes on the Chaná, or on the Charrúa, or the Guaraní. Or on any of the peoples who traveled this part of the world when Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina were still a single land with no borders other than rivers.

The history that little Evangelina learned in the classroom was much shorter… it began with Columbus setting foot in America.

[Evangelina]: Every October 12, we made the caravels and Columbus came, and he was the greatest idol there could be, because he had arrived with new things to bring everything that was beautiful.

[Emilia]: Until one afternoon, when Evangelina was about 13 years old, around 1990, a Geography teacher uttered for the first time that word she had heard so many times in her own home. It was a class on the indigenous peoples of Entre Ríos, and Evangelina saw her teacher writing names on the blackboard, one by one: Charrúa, Guaraní… Chaná.

[Emilia]: And when she heard that name, without much thought, she raised her hand. The teacher gestured for her to speak.

[Evangelina]: And he says, “Yes,” and I tell him… “I am a Chaná descendant.”

[Emilia]: It was the first time she had ever said it out loud and in front of others outside her family. For a few seconds, the class continued as if nothing had happened. But the teacher remained thoughtful, as if he did not quite understand what she was saying. And he asked her:

[Evangelina]: “But is it true? Look, the Chaná don’t exist anymore, look, the Chaná are gone.”

[Emilia]: Both of them, the teacher and Evangelina, seemed equally confused: he because of what a rather timid student was telling him, and she because of his reaction. The first thing she thought was that the teacher was lying to her. How could they not exist? So who were her grandmother, her father, herself? In any case, Evangelina appreciated that teacher, she liked his classes.

So she replied:

[Evangelina]: “Yes, yes, my family is Chaná, my grandmother,” I told him, “My grandmother was Chaná.”

[Emilia]: But the teacher insisted that that was impossible.

[Evangelina]: “But look, the Chaná don’t exist, the Chaná disappeared, nothing more is known about the Chaná than the history of what a certain man called Larrañaga said…”

[Emilia]: Dámaso Antonio Larrañaga. Evangelina had never heard that name of the last person to leave a written record of the Chaná. A Uruguayan priest and naturalist, who in 1815 interviewed three old men whom he identified as Chaná. They were lenguaraces, the term used back then to refer to people who spoke two languages—their own native language and the Spanish of the conquerors. Larrañaga described them as three laconic men, rather secretive, who spoke very little.

[Emilia]: After that meeting, he wrote a document in which he compiled words and details about the Chaná language. After that record, there was nothing else, and almost two centuries had passed. As if the Chaná had disappeared from the world. And, in fact, that is what the history books said: that, like so many other peoples, they had been devastated by the European conquest.

[Emilia]: Evangelina knew nothing of that entire story, so she didn’t expect what happened seconds later: the laughter of her classmates that started first as a whisper and finally turned to loud laughter.

She would never forget the hurtful words that were said to her on that day.

[Evangelina]: “Oh, so you are an Indian, of course, no wonder you are black,” that you are this, that you are that… and it went on for a day, two, three…

[Emilia]: The teasing, the racist jokes… now that she had accidentally revealed her secret, at school Evangelina could feel all eyes on her.

[Evangelina]: They would say to me, “Here comes the indigenous black girl,” or they would mouth things, oh, oh, oh… And say many things that, to be honest, hurt me, and I felt bad, I felt sick, and I decided not to say anything else. In other words, I kept silent.

[Emilia]: Until that day, being a Chaná descendant had not been anything strange for her, much less something to be ashamed of. However, she had often felt discriminated against because of the color of her skin, which was brown like her father’s and her grandmother’s. But that day at school, for the first time, she felt like someone different from the rest of her classmates. Or at least from how they saw themselves—white or, at the most, mestizo. Whereas now she, in front of everyone’s eyes, was an indigenous person. And as she had just learned, being indigenous in Argentina… there seemed to be no place for it. Somehow, she understood for the first time the silence of her grandmother Morocha.

And Evangelina, who was just entering her teenage years, began to wonder who she really was:

[Evangelina]: Where do I belong? What group do I go to? Because I can’t be with whites; and indigenous people… nobody, nobody was indigenous, nobody was a descendant of indigenous people…

[Emilia]: It was the 90s, and to give you an idea, the national census in Argentina did not even include a question about belonging to the native peoples. It was as if they just did not exist.

[Evangelina]: Being indigenous was like something despicable… You had better not say anything. You had better be silent and accept the color of your skin because, well, you were just more sun-tanned than the others, but that was all.

[Emilia]: So she decided to do just that: be silent. And she did. She never mentioned her Chaná heritage at school, either in front of her friends or with anyone. And she didn’t tell her parents what had happened, either. She didn’t know it, but by doing this she was also fulfilling a part of her Chaná legacy. After all, silence had always been a survival strategy for them.

But it was around that same time, a few months later, that her father decided it was finally time to talk about it with her. He realized that his daughter was old enough to understand her history. He, Blas Jaime, was a municipal employee, a serious but charismatic man in his own way, who had made his way in the world without going to school. That day, he looked up from the newspaper and said:

[Evangelina]: “As you know, we are Chaná. If you would like to learn, I can teach you. It is up to the women, not me, but all my sisters died and your grandmother taught me because she had no one to teach.”

[Emilia]: Evangelina knew something, not much, of what she had been hearing in conversations during her childhood, but she did not know the full story. That day, Blas explained to her that, although among the Chaná it was the women who were in charge of transmitting language and culture, his three sisters had died of typhus when they were little. So her mother had had to make a decision that no other Chaná had made before: choose one of her sons and teach him those things. And she chose him.

Like Morocha, Blas also was a person of few words, and that day he didn’t say much more to her other than that: If she wanted, he could teach her. But he didn’t tell her other important things. He did not explain, for example, that what he was offering her was an enormous honor for a Chaná, reserved only for the most intelligent women, nor that had her grandmother Morocha, whom she had loved so much, been one of them, an adá o yendén, in the Chaná language, a “woman memory keeper.” The last of her family.

He did not tell her either—and it would take Evangelina a long time to find out—that when he was 12 years old, Morocha had given him lessons in which she patiently led him through the long history of the Chaná people. Blas had learned all about the life of his ancestors. That they used to break pots to release the spirits when they left a camp, that they decorated the clothes of the dead with parrots so they could converse with them. That Chaná men were forbidden to assault women. She told him about silent villages, where not only did the children not cry, but also the dogs did not bark, because their vocal cords were cut.

Those classes had lasted more than a decade and, in them, Morocha had also told him stories of Chaná who had had the tip of their tongues cut off by the conquistadors for speaking their own language. And for that same reason, she told him that he had to continue that way, protected by a cloak of silence. He couldn’t talk to anyone or spread what he had learned until he received a sign. Though she didn’t tell him what that sign would be.

But, as we said, at that time Blas did not tell his daughter about all this. He just told her that if she wanted, he could teach her what his mother had taught him. And Evangelina’s response was not what he expected:

[Evangelina]: I said, “No, I don’t want to, I don’t want to learn anything, I don’t want to know anything.”

[Emilia]: After what had happened at school, she was afraid that if she accepted that part of her life, the discrimination against her would continue. She was afraid that even her mother’s family would reject her.

[Evangelina]: But it seemed to me that they would stop greeting me or stop loving me because I said that I was a descendant of indigenous people.

[Emilia]: So no: she wanted to be a teenager like any other. Study, go out with her friends, do her things without carrying any stories about herself. Without anyone making fun of her again. She was not interested in the Chaná culture, her ancestors or their secret language; she just wanted to be left alone.

And so she lived the next ten years, trying to leave all that behind, always with the feeling of being part of a history that was denied in her country. The thing is that Argentina built part of its identity on this absurd idea that “we got off the boats,” which was even repeated by the current President: That we descend from European immigrants who arrived in the country since the end of the 19th century. As if this were, in quotes, “a country without indigenous people.” It was not until 2001, when the National Census included the question about belonging to an indigenous people, that statistics began to show how the native peoples are still present in Argentina.

Evangelina does not remember what she answered in that census. And although that morning at school when she decided to identify herself as Chaná had happened many years before, it was still a painful memory, and that is why that part of her identity was kept inside her, deep inside her.

[Evangelina]: I kept it as a memory for myself, about my grandmother, I never spoke about it again, with anyone.

[Emilia]: But just because she didn’t talk about it with anyone didn’t mean it wasn’t there, always dormant. Some nights, when she stayed up studying until dawn to become a Tourism Technician, the memory of her grandmother came to her head, over and over again. And so did the unanswered questions:

[Evangelina]: And it made me wonder what my grandmother could have taught me if she had lived much longer than she did live with me.

[Emilia]: During those student years, Evangelina had several opportunities to say “I am Chaná” again, and she always preferred silence. But something changed around 2001. By that time, at the age of 23, Evangelina had married and had a baby. And with the arrival of her son, when she held him in her arms, and she looked at him—so small, so new to the world, she felt the weight of having denied a part of herself.

[Evangelina]: I started to think about what kind of human being I want this person to be, who chose me to be his mother. I have to guide him along a good path. And if I keep on being silent, what kind of son am I going to raise if I keep teaching him to keep quiet?

[Emilia]: One thing seemed clear to her: She could not guide him from a place of silence. About that same time, around 2001, Evangelina and her father, Blas, had a falling out and stopped talking. The relationship between them became complicated when, at the age of 67, he left his wife, Inés, and started a new family with another woman.

But Evangelina did receive news of her father from time to time. She learned through other relatives that Blas had begun to break the silence he had kept for so many years. Now retired, he worried that everything he had learned from his ancestors would be lost with him. He wanted to find someone with whom he could speak Chaná as, so many years ago, he had spoken with his mother. He assumed this could not be with his daughter, but perhaps there were other descendants in Entre Ríos or some other area of the country. People who, like him, would have learned at home, and would have followed the same advice: remember and keep silent.

So Blas started by going on a friend’s radio show, where he talked about the Chaná culture, hoping someone would show up, but nothing happened. It seemed as if he was the last Chaná on earth.

Three years went on like that, until one day in 2004, Blas was driving his car when he came across an acquaintance, who asked him to drive him home because he wanted to introduce him to a friend. She was a descendant of indigenous people and was there to participate in some activities that were going to take place in honor of the native peoples, who by then were beginning, little by little, to be more visible.

Evangelina told me she did not know the details of what that conversation had been like. And when I asked her whether I could talk to Blas, she explained that it was difficult. He is 88 years old now and has hearing problems. But she gave me his number anyway. I thought it was important for him to be the one to tell me this part of the story, of which he was the protagonist and the only witness, because by then, Evangelina did not speak to him.

We connected through a WhatsApp call. He felt fine that morning, so he made an effort to remember the details of those days when his life changed forever, almost 20 years ago.

He still remembered clearly the words of his friend to the woman who was waiting for him at his house.

[Blas]: Then he introduced me… He says, “This brother is Chaná; he is the only Chaná speaker left.”

[Emilia]: The woman, who knew many descendants of other indigenous peoples, looked at him incredulously, as if he were a ghost. And the response she gave him was very similar to the one Evangelina had heard in the classroom many years before. She told him:

[Blas]: “But it cannot be—there is no Chaná alive, the Chaná no longer exist.”

[Emilia]: And, at that moment, Blas thought the same thing his daughter had in front of that teacher. Whatdid she mean, the Chaná didn’t exist anymore—when he was right there, standing in front of her?

He answered her with some humor, as he always did:

[Blas]: “Well,” I said, “ma’am, I exist. Touch me if you want; I’m made of flesh and blood.”

[Emilia]: They talked for a while, and before saying goodbye, the woman invited him to participate in some activities they planned to conduct a few days later in a theater with children from Paraná schools. Blas thought about it for a few seconds.

[Blas]: And I realized that was the sign.

[Emilia]: At that moment, standing in that house where he had come almost by chance, Blas knew. That invitation to speak in public about the Chaná was the sign his mother had told him about more than fifty years earlier.

The time had come to finally break the silence.

[Daniel]: We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. Before the break, we heard the story of Evangelina, a descendant of the Chaná culture, who, through all her life, had refused to follow her family’s secret tradition.

But her father, Blas, had decided to speak in public about what they had been hiding for decades. And that would change everything for both of them.

Emilia Erbetta continues the story.

[Emilia]: The activity in the theater was scheduled for the following Saturday. In the audience were more than 700 children from different schools. When Blas arrived, he was seated on the stage along with some representatives of different indigenous peoples. A few minutes later, Blas heard the woman who was acting as the master of ceremonies say, “Now we will hear from an elderly native man.”

[Blas]: I looked around to see who the elderly man was… And she says, “It’s you, Don Jaime, you.”

[Emilia]: Blas took the microphone, said a few words in Chaná, and began to talk about the life of the children in his town. He said they ate a lot of corn, they fished by making gutters on the river bed—things that could interest those boys and girls looking at him from the audience.

[Blas]: And, well, I felt that I was doing my duty, what I was born to do. I started talking, and from the moment I spoke for the first time, I never stopped doing it, because they wouldn’t let me.

[Emilia]: In fact, when he left the theater, some journalists were waiting for him at the door, to interview him for a Paraná television channel and for a local newspaper. In their articles, they said that Blas was an authentic Chaná descendant and not only that, but he spoke the lost language of his ancestors.

That information immediately caught the attention of Tirso Fiorotto, a journalist who wrote for La Nación, one of the most important newspapers in Argentina, and who would be the one to change the lives of Blas and Evangelina forever. It even seemed too good to be true: How could there be a retired man in Entre Ríos who spoke a dead language?

This is Tirso:

[Tirso Fiorotto]: I realized at once that there was an extraordinary treasure there. I went in search of the Chaná language—I knew it was a people who had disappeared as a community 200 years ago.

[Emilia]: He began asking questions to see whether anyone knew him, and a local fisherman guided him to a neighborhood in the ravines of the Paraná River, with modest homes and dirt streets, where Blas lived with his new wife and a young son. It was 2005 and Tirso was still carrying one of those recorders that used cassettes. Before starting, he pressed REC. He wanted to talk about the language, but Blas wanted to tell him everything about the culture of his people.

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Blas]: That is why they taught their children not to cry, their dogs not to bark, and they spoke softly…

[Emilia]: Tirso began to delve into Blas’s memory, looking, above all, for words. He asked what they called the leaves of the trees, the fingers of the hands, or the most dangerous animal of the mountain, the puma.

(SOUNDBYTE ARCHIVE)

[Blas]: Well, they were buní, buni… Big cat, añi… because the puma was yellow.

[Emilia]: They talked for a long time and, when he left Blas’s house, Tirso couldn’t believe what he had just heard.

[Tirso]: What I had found—no, it surpassed everything, it surpassed everything… In the almost 40 years that I have been a journalist, I have never come home so shocked by a story.

[Emilia]: He was moved, and it was noticeable in the article he published in La Nación. He presented Blas as a man with a peaceful expression, who treasured the language of his ancestors. He told how he had learned to speak it. And he cited things that had fascinated him during the interview, such as how the Chaná named, for example, smoke, putting together several words that together meant son of fire that made the person it burned cry.

The article reached the ears of a linguist from Buenos Aires, Pedro Viegas Barros, who wrote asking him for more information about Blas. What he had read had left him perplexed. He had been researching the native languages of Latin America for years, it was his doctoral topic, and all the studies and documents he had read spoke of Chaná as one of hundreds of indigenous languages that had disappeared after the conquest. It couldn’t be.

They exchanged several emails, and Tirso sent him the three cassettes of the interview by parcel post. Almost three hours of recording, which persuaded the linguist to travel as soon as possible to meet Blas in person.

Viegas Barros did not answer our requests for an interview, but he explained in several places that he needed only 15 minutes with Blas to realize that it was true. He was in front of someone with mastery of a language that was believed to be extinct. What Blas knew required too deep a linguistic knowledge to have been learned by occasional reading.

He even explained it to Tirso on one occasion:

[Tirso]: We discussed this with Pedro Viegas Barros, and he had pointed out to me that it is impossible for some of those expressions to have been invented by a common person, unless he is a very seasoned linguist.

[Emilia]: What was known of the Chaná language was not much more than what the Uruguayan naturalist mentioned earlier, Larrañaga, had written, the last to interview three Chaná in 1815. That its sounds were rather guttural or that it didn’t have the F neither the LL nor the Z nor the Ñ.

However, that record, of barely 13 pages, was more than a technical note. It was also a testimony of how the Chaná saw the world. Larrañaga noted, for example, that they did not know words to say “god”, “soul,” “understanding” or “will,” but they did know “memory,” “interior” and “heart.”

But Blas knew much more. For this reason, with the linguist they began an almost artisan work to rescue it from the nooks of his brain: they compiled words and reconstructed the grammar and phonology. They even toured the Paraná River looking for more descendants who had learned the language as children, but found no one.

Along the way, Blas began to become more and more famous. He was like a small local celebrity. Evangelina was still fighting with him, but she was still following all the news about her father. And in that way she had begun to understand what she had turned her back on all that time: not only her identity, but a culture and, above all, the legacy of her grandmother Morocha.

However, seeing her father in the media gave her mixed feelings. On one hand, it made her wonder about her future: it scared her how this sudden fame could impact her and her family in such a small town. Before she was Evangelina. Now she was the daughter of the last Chaná.

[Evangelina]: Well, what is going to follow now? How is this going to affect us?

[Emilia]: But at the same time, she felt liberated.

[Evangelina]: Some kind of relief to finally be able to say where I come from, who I am, so others won’t say things that hurt me.

[Emilia]: Suddenly, being Chaná was something valued. But that was not the only thing that reassured her, but also knowing that her father had managed to fulfill, in his own way, part of the mission that she had refused: to preserve the language. And when she thought about it, she couldn’t help but wonder…

[Evangelina]: And if he had said no, like I did? This wouldn’t exist everything would have been lost. Luckily he said yes and didn’t say no like I did.

[Emilia]: Evangelina does not remember the exact date, but she knows that it was around 2010 or perhaps a year later when she ran into Blas in a square in the center of Paraná. That day she was in a hurry, tired, on her way home after work, but she saw him from afar and she decided to go over to say hello. They hadn’t spoken for almost a decade, and she not only noticed him older, of course, but also sad, as if worried. And although they carried conflicts, at that moment, under the midday sun, the years of anger began to be left behind.

Evangelina invited her father to her house and on the way she suggested that they buy something to eat. But when they arrived they barely touched the food: they needed to talk. Blas told her that he was still working with the linguist and that he received more and more inquiries from people who wanted to know about the Chaná language. They asked him for materials, information, and he did not know what to answer. They even invited him to language conferences throughout the country. Shortly before, UNESCO had included Chaná as a language believed to be extinct in its Atlas of Languages of the World, and had declared Blas the “last speaking Chaná.”

Blas didn’t know how to deal with so much fame. All his life he had written down by hand what he remembered about the language and had made some photocopies of it, but he had no computer or email, and he felt overwhelmed with all those requests.

Evangelina felt that she had to help him. After all, it was her dad. So they began to see each other often and she began to help him with all of this: she opened an email account for him and transferred to her computer all the notes that Blas had written by hand.

[Blas]: I had to memorize a lot and look for old notes that I had in some papers… I was always writing something, but I didn’t publish it or show it to anyone; I kept it. Well, that worked for me.

[Emilia]: Evangelina also began to accompany him in talks, conferences and interviews. Blas never refused an invitation, and he still couldn’t believe so much fuss around him.

[Evangelina]: There a kind of movement started. Love for the Chaná was awakened, knowing there was someone who knew the language. And he always told me: “I never thought that people were interested in what we know.”

[Emilia]: They called him from schools, museums… in fact, Blas had started teaching Chaná in an anthropological museum in Paraná, and Evangelina joined, at first, as one more student. They came from all over the province: retirees, high school or university students interested in the roots of Argentina. She sat with the rest and saw how her father tried to put on a blackboard the language that he had kept for 70 years.

Blas knew a lot about the subject, but he had never taught a class, nor did he really know how to do it. Evangelina noticed that he often beat around the bush or found it difficult to give more specific explanations.

[Evangelina]: So I said, “I have to help him.” Because if he is trying to save what is ours, our family, with the way he is doing it, he is not going anywhere.

[Emilia]: For this reason, they also began to meet alone, outside of class hours. Evangelina would make a cake, prepare the mate, and they would sit together for hours, just as she had done with Morocha. Blas wrote down words on a piece of paper and their meaning or some kind of description. And she went through everything on the computer and was ordering the words alphabetically.

That way, almost without realizing it, she became a kind of archivist of the Chaná language. She organized into Word documents and Excel spreadsheets everything that her father, her grandmother, and the Chaná who lived before them had passed on through whispers. It became almost an obsession: to rescue from the passage of time everything that her father knew, because she saw how age began to eat little by little his memory.

And in those encounters, while Evangelina’s son repeated those words that were so old and at the same time so new like a game, she was learning to speak Chaná.

[Evangelina]: I remember that we began to say “Njarú,” which is a greeting, which is the first thing that is taught in any language… to say hello, to say hello. “How are you?” “Retam chá…” he would say, “retam chá.” And I had to answer him, so I had to answer him “chao ble,” if I was okay. “I’m fine.”

[Emilia]: It wasn’t hard for Evangelina to learn, or so it seemed to her, as if that language had been stored in some part of her throughout her life. Another of the first words she learned to say was “woman.”

[Evangelina]: He told me, “You are an Adá.” I said “Oh, of course… a woman”…

[Emilia]: And that word, Adá, was key to understanding the meaning of another very important term for the Chaná: Adá o yenden.

[Evangelina]: Ada o yenden is a woman, a memory keeper, but oyé means hiding… Hiding, and enden is memory, that is, hiding the memory of the Chaná.

[Emilia]: Adá o yenden, the woman memory keeper. What Morocha had been and, before her, her great-grandmother. More than a word, it was a destiny, the same one that, unknown to her, her grandmother had foreshadowed for her and to which she had turned her back. But the more she learned about her ancestors, about the way in which women went into the river to give birth and the children learned to swim before they could walk… all that history that her grandmother had fought to protect, Evangelina felt more and more connected with her.

[Evangelina]: I understood many things… when she was silent, thoughtful. Thinking while sitting under the sun.

[Emilia]: She remembered her lying under the grapefruit tree in the back of her house. And she believed that, in those moments, surely her grandmother was thinking about all this that she was learning now.

She was remembering everything it had cost her a lifetime to protect.

In 2013, all of Blas’s work with the linguist Viegas Barros resulted in the publication of the first dictionary of the Chaná language. And five years later, after the premiere of a couple of documentaries about him, Blas even gave a TED talk. Suddenly, there was so much interest in this native town that a cartoon was even made about the adventures of a little Chaná boy. And in one episode the animated version of Blas came out, dressed as a Chaná, barechested and in the middle of the mountain.

Blas recorded his voice for the episode:

[Blas_cartoon]: Njárug. I am Blas Jaime, Agó Acoé Inó, which means “dog without an owner.” Together we will remember the words that we have learned in today’s chapter…

[Emilia]: Evangelina continued to accompany him in everything, but she remained in the shadows. There she felt more comfortable.

[Evangelina]: I never really wanted the leading role that my dad has. He was the one who spoke and the one who always said, “She has to be the one, she has to be the one.”

[Emilia]: She had to be the next memory keeper. He told her in front of the students, in the interviews… And when the two of them were alone too.

[Evangelina]: And the day comes when he tells me, “Well, now it’s your turn.”

[Emilia]: That time, Evangelina’s answer was different. Now she did understand what her role was in that story, that it was much bigger than her. And she was willing to accept it, albeit with conditions.

[Evangelina]: I said yes, but I didn’t take the words adá o yenden as a title for me. Instead I decided… that I was going to teach.

[Emilia]: She didn’t need a title. It was enough for her to accept what she had always been.

[Evangelina]: I think I’m a Chaná… who doesn’t want the history of my ancestors, or my forefathers, to be forgotten.

[Emilia]: Evangelina joined her father’s classes, accompanying him as a teacher. And sometimes, when he couldn’t be in front of the class, she would take care of it. That way, they taught together for several years, until in March 2020, with the pandemic, activities at the museum were interrupted. Blas didn’t know how to use the computer and couldn’t teach online, but Evangelina did, and she didn’t want all the work they were doing to be lost.

So, she asked her father for permission to continue his classes on her own, online. She had discovered that she liked to do it: prepare the meetings by imagining everyday scenes from the old Chaná camps and, based on that, decide which words her students would learn that day.

She felt that something had begun to grow in her. Something planted inside of her since she was a child. But not a seed that sprouts quickly, but one that takes longer to take root.

[Evangelina]: It was as if someone planted something there and it kept on circling until little by little it started, as I became older, to say, “Well, I am this; whoever doesn’t like it can continue on his path.” Why do you have to hide what we were, what we are? We are still here.

[Emilia]: In August last year, Evangelina invited me to join one of her classes via Zoom. The name was Taparí Virtual-mití-Chaná, Chaná meeting. At 9 in the morning, when the camera turned on, I saw her sitting in front of her computer, with a mate in her hand. We were seven people connected and among us, there was a girl who was also a descendant of Chaná.

The students had worked all week on translations from Spanish into Chaná and, for the first time, they were going to read them in front of the rest. But first, Evangelina was silent for a few seconds to officially start the class.

It seemed as if she was about to start a ceremony…

[Emilia]: I saw her raise her hands, put them close to her face…

[Evangelina]: …we greet each other with our hands up to say that we are friends and not enemies and that we do not bring any kind of weapons. And that is the Chaná greeting that we are going to have…

[Emilia]: It was almost two hours in which I saw her concentrating on each word her students said, correcting their pronunciation and, above all, explaining to them how those words reflected the Chaná way of seeing the world.

And now, every time she prepares a class, she doesn’t do it for her father or for the UNESCO Atlas of Languages, or for the linguists: she does it for her grandmother, Morocha, for the years in which she had to live in silence, and for all the other Chaná women before her. She doesn’t know whether projecting an almost phantom language into the future was her destiny or not. Maybe or maybe not… what she is sure of is one thing:

[Evangelina]: I don’t want them to call us any longer the silent people any longer. From now on, they will know who the Chaná were, who the Chaná are, and who the Chaná are going to be.

[Emilia]: The silence of the Chaná ended with her.

[Daniel]: According to the 2010 census data, which are the latest available, today more than 950,000 people in Argentina recognize themselves as belonging to or descended from an original people, 2.4% of the country’s total population. In total, 39 indigenous peoples live in the territory that we now call Argentina, some in very small communities and others more numerous.

Emilia Erbetta is a production assistant for Radio Ambulante and lives in Buenos Aires.

This story was edited by Camila Segura, Nicolás Alonso and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design and music are by Ana Tuirán.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Lisette Arévalo, Pablo Argüelles, Andrés Azpiri, Diego Corzo, José Díaz, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Juan David Naranjo, Rémy Lozano, Ana Pais, Laura Rojas Aponte, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill, David Trujillo , Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Selene Mazón is our production intern.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.