A City Without Ink | Translation

Share:

► Click here to return to the episode official page, or here to see all the episodes.

► Join Deambulantes. Our membership program help us continue covering Latin America.

►Do you listen Radio Ambulante to improve your Spanish? We have something extra for you: try our app, designed for Spanish learners who want to study with our episodes.

Translated by MC Editorial

[Daniel Alarcón]: This is Radio Ambulante from NPR. I’m Daniel Alarcón.

For writer and journalist Tamara de Anda, March 9, 2022 was a day like any other. In the morning she went to her job at a public TV channel in Mexico City, she made recordings in different parts of the city, and at the end of the day she got ready to go out. Her co-workers offered to take her to the subway station, at the City Hall of Cuauhtémoc, the area where she has lived for several years.

They left her a block and a half from the station and she began to walk down the street…

[Tamara de Anda]: Which is where the backs of the stands face, usually tin stands… Because the stands have this huge canvas that is the back.

[Daniel]: On this canvas, as Tamara calls it, the owners of the metal stands—who sell things and offer services of all kinds—use the opportunity to write hand-painted ads identifying their businesses to distinguish them from others. I mean, signs. There is everything. Some are quite literal but nonetheless striking, like the drawing of a key and the phrase “keys in a minute.” But others can get very creative, like a stand where they cut your hair, with a picture of Edward, the main character in the movie Edward Scissorhands. Or one that sells “tacos a la plancha,” with a drawing of Marge Simpson raising a taco in the air and Homer with a glass of foamy beer.

Ever since her childhood, and especially in her teenage years, Tamara began to be fascinated by these signs. And little by little, they became an obsession.

[Tamara]: In recent years, I have become something like a street art hunter. It is… it is something that I like to document, collect. Just for the sake of having it. And it is very exciting. It… my neurotransmitters kick in. It is my addiction (laughs).

[Daniel]: So on March 9, as Tamara was walking to the subway station and looking out for new signs to add to her collection, she realized that something was not right. The urban landscape was completely changed. And instead of running into a torta, that is, a sandwich…

[Tamara]: I came across a stand painted white, with the horrible logo of the current administration of Cuauhtémoc City Hall, with the slogan “This is your house”… Huh?

[Daniel]: She looked at the neighboring stand that sold tacos with sauce and it was the same. And across the street, the chicken broth…

[Tamara]: Goodbye chicken broth. “Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office.” The juices and smoothies that normally make up this still life—which is rather very, very alive with fruits and colors and snacks. “Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office.” And I saw that all the stands had the Mayor’s Office logo, with the motto “This is your house.” And I said, “Nooo!”

[Daniel]: Her beloved signs were gone. And with them one of the traits that she loved the most about her city. But Tamara has never been one to sit idly by. And that day she began a personal mission, which would become collective: to save the popular street art of Mexico City.

We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Our senior producer Lisette Arévalo picks up the story.

[Lisette Arévalo]: We’ll come back to the moment when Tamara realized that all her beloved and colorful signs were gone. Because, to really understand her reaction, you need to know more about the connection she has with them ever since she was little.

[Tamara]: Those were images that made me laugh. That made me wonder what the creative process behind them was.

[Lisette]: When she walked through the streets with her family, she was caught up by the colors and artistic expressions that covered the city. She remembers seeing the ice cream carts in her neighborhood, decorated with metallic and colorful letters that announced the flavors: lemon, strawberry, tamarind… And just by seeing them, Tamara felt she could already taste them.

[Tamara]: I would see those very colorful, fat sandwiches in the streets, and I saw the little pigs and the objects with anthropomorphic characteristics.

[Lisette]: There were signs with unique adaptations of the most popular cartoons of the time. Like Mickey Mouse drawings of various colors: green, purple—all psychedelic.

[Tamara]: Bugs Bunny in Mexican situations, eating his popsicle, of course, and, of course, eating his lemon ice. And naturally, the Tasmanian Devil devouring all these treats that were just outside the school building…

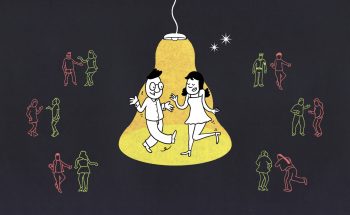

[Lisette]: And surrounded by those picturesque signs, Tamara felt happy. She felt she could connect more with that urban art that was unlike anything usually found in large museums or art galleries.

[Tamara]: I appreciated that art with which I had a daily relationship, which spoke directly to me as a consumer of all those products, and which accompanied my experience of eating on the street.

[Lisette]: Not only that. The signs accompanied Tamara at many other times and places in Mexico City. She told me about one in particular:

[Tamara]: It was a stand called “La Torta Feliz .” It was special because it was surrounded by a blazing yellow comet trail—canary yellow, like the ones they use in comic books. So it was like a taaa, ta, taaan! Like a dramatic entrance of this sandwich (laughs).

[Lisette]: Tamara laughs just remembering it. Because in that picture, the torta—or sandwich—did not look very happy. It was quite thin, pale, and did not have a very appetizing appearance… But Tamara also laughs because just by remembering it, she is transported to the time when she was in high school, the late 90s.

[Tamara]: Walking by it meant that I was going to see my friends, that I was going to start a tour of the city, that we were going to a concert, that we were going to meet up, and listen to music. So passing by the “Torta Feliz” stand was the first sign that it was going to be a night to remember.

[Lisette]: The stall became a place of worship for his group of friends. In fact, they took a picture with the sign, which she keeps to this day. It’s one of the few records she has of the signs from that time. She didn’t have a digital camera, and buying film was too expensive for a high school student. So she was content to observe the signs as she walked through the city and keep them in her memory.

A few years later, in the early 2000s, Tamara realized that she wasn’t the only one obsessed with street art. The Palacio de Bellas Artes, the top cultural venue in Mexico City, held an exhibition called “ABCDF Graphic Dictionary of Mexico City,” and it was a photographic compendium of objects and details.

[Tamara]: Which together could make up the personality of what Mexico City is, but don’t have many things in common. In other words, Mexico City is heterogeneous, chaotic, noisy. So let’s stop trying to believe that there is only one way or one adjective to describe us. That is impossible.

[Lisette]: And one of the things that was included in this exhibition was popular street art.

[Tamara]: So that recognition seemed fascinating to me, on top of the fact that I was given the tools to name with words all those things that I appreciated and that moved me about Mexico City.

[Lisette]: At first, the exhibition was a source of frustration for her because she would have loved to be able to take all the pictures she wanted of the street art she saw. But at the same time it was an inspiration for the future.

When she was in college, she bought a video camera for her communication class, and it could also take photographs…

[Tamara]: I don’t think it had even one megapixel. It took some horrendous pictures, but those were the first pictures of popular art that I took when I went around with my camera—but the camera was a big, bulky thing, in addition to what it had cost me, which was a fortune in student pesos.

[Lisette]: She was afraid it might be stolen, so she took photos only occasionally. By 2005 or 2006, she had her first cell phone with a camera, and then she began to photograph everything she could and uploaded it to her blog.

With time and the advent of social media, Tamara transferred her posts to Twitter and mainly to Instagram. Her account is full of pictures she has taken of signs on metal stands, on walls, on commercial premises…

[Lisette]: And well, that’s why it was so shocking to her, when that day in March 2022, she found that the Mayor’s Office had erased the signs.

[Tamara]: I felt very powerless and very frustrated because, well, I’m a girl who makes a lot of noise on social media, but also… well, I know there are more people who are interested and who like popular art, but how can we do something? How are we going to articulate to put an end to this? I had no idea what to do.

[Lisette]: She felt that a virus had arrived in her neighborhood and had dressed in uniform all the stands that she was so fond of. And for her, that virus had a first and last name: Sandra Cuevas, the mayor of Cuauhtémoc.

Here I have to explain something: Mexico City is divided into 16 districts, and each one has its own mayor elected by popular vote. And in turn, the mayors answer to the Head of Government of the entire city.

Sandra Cuevas took office as mayor of Cuauhtémoc in October 2021. Among her government plans was one to create a “Comprehensive Day for the Improvement of the Urban Environment,” which sought, among other things, to separate street stands one meter apart from each other and for owners to keep their work area clean. In addition, she sought to achieve —quote-unquote— “beauty” throughout the urban setting and coexistence—quote-unquote— “in peace and harmony among all.”

The plan made absolutely no mention of painting the stands one single color. So, for Tamara, erasing the signs sent a clear message: popular art had to disappear if that supposed beauty was to be attained.

So she did the only thing in her power: she took her outrage to social media. She opened her Instagram account to upload a story, took a picture, and wrote:

[Tamara]: This administration of the Cuauhtémoc mayor has a crusade against popular art on street stands. Just because your brain is gray and blueish-white does not mean that the mayor’s office has to be those same colors, Sandra Cuevas. Angry emoji.

[Lisette]: After posting, Tamara put away her cell phone, got on the subway and went home. She received the occasional comment from her Instagram acquaintances sharing her indignation. But the issue didn’t go beyond that, and Tamara didn’t do or say anything more about it.

[Tamara]: I think subconsciously a part of me wanted to just crawl under the blanket, wait for this administration to pass, and for popular art to come back, like nature finding its way.

[Lisette]: But about two months later, she received a video published by the Instagram account “PinturaFresca.mx”, managed by Hugo Mendoza. It contained the question, “What happened to the signs in Cuauhtémoc?” and the merchants responded with their testimonials.

(SOUNDBITE ARCHIVE)

[Merchant 1]: They told us to erase our sign we had and they were going to put up theirs.

[Merchant 2]: They never paint our stands for us. They tell us, “You know what? We need you to paint the stands. You know what? For example, the stand across the way there, remove the canvas, we want it white,” and they have to make it white. Otherwise, they fine us, they close us down. Or whatever.

[Lisette]: The video was filled with comments and emojis of angry, sad and tearful faces for the almost 1,500 stands that had lost their identity…

[Tamara]: That video went viral, so the subject of the signs slipped into the conversation with people. They said, “We are not alone, we are not three people crying in front of empty walls,” as someone put it on Twitter.

[Lisette]: And after the video went viral, everything broke out.

[Tamara]: A friend called Aldo Solano Rojas, who is an art historian, wrote to me and said:

[Aldo Solano]: What are we going to do? Because Tamara has been constantly posting for years all the signs that she sees and that she finds funny. And I am also a heavy user of public space, right? And I observe it and study it. That’s what I do: I investigate it.

[Lisette]: And just like Tamara, Aldo also noticed the changes that were taking place in the zone.

[Aldo]: I refused for a while, like a week or two weeks, to even watch the video because I got very angry and I did not want to get angry, but then I embraced my anger, and so we decided to contact more people that we knew were worried about that… including Hugo, the person who made the video.

[Tamara]: And I wrote to Sofía Riojas, who is a restorer and has a group called Restorers with Glitter…

[Lisette]: They also contacted the sign maker Alina Kiliwa, and Yuriko Hiray, a specialist in communications and digital media. They set up a WhatsApp group chat and invited more people who were indignant, until they put together a network of a little over 30 people.

[Tamara]: And that’s how Rechida was born overnight. The Chilanga Network in Defense of Popular Art and Graphics.

[Daniel]: And that would be the start of a much bigger action in the city. We’ll be back after a break.

[MIDROLL]

[Daniel]: We’re back with Radio Ambulante. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Before the break, journalist Tamara de Anda and art historian Aldo Solano Rojas decided to unite with more people to create Rechida, the Chilanga Network in Defense of Popular Art and Graphics. The thing is that the war for control of the aesthetics of public spaces is not something recent.

Lisette continues the story.

[Lisette]: Since it was 2022, one of the first actions they took was to open an Instagram account. In their first post they uploaded a carousel of photos including a flyer with a picture of a sandwich, which said: “There was once a sign here, but the Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office erased it.” The text of the post said that the signs should be considered popular art that deserves to be preserved, cared for, and studied. And it went on…

[Tamara]: The destruction of these murals is an attack on the culture of our city and its citizens. It is an insult to the sign artists and those who paid for their work. We do not want a sterile and colorless city. CHILANGO POPULAR ART must be valued and defended.

[Lisette]: And it ended by saying, “Yes to signs, yes to popular art, yes to our own public image free of institutional logos. Yes to street stands full of colors, letters and brightness.”

[Tamara]: And with that, there was a way for people to channel all their anger, their indignation, which we really did not expect.

[Lisette]: People began to replicate the hashtag that Rechida used for its publication: #ConLosRótulosNo, and they shared everything. Memes, of course, were everywhere. One of them, for example, compared Sandra Cuevas to the infamous character from the Harry Potter saga, Dolores Umbridge, known for her intolerance of differences and her authoritarianism.

Artists began to make illustrations paying homage to those signs that were no longer there. And people began to share photos of the now-defunct signs to create a digital archive, a memory bank of what was once there.

Tamara was not far behind, of course. She is part of Standuperras, a feminist comedy group that mainly does cabaret theater. From that space, Tamara spontaneously created a character to parody what was happening. She bought a black wig with long, straight hair, painted her lips red, and taped a sketch called Sandra Huevas. And it went like this:

[Tamara]: I’m Sandra Huevas and I don’t like the poor. And there is a very nice saying that says “you are what you eat,” and if you eat like the poor, then you will stay poor. In my administration we are discouraging people from eating at these stands for the poor; that’s why they will no longer be able to tell them apart and they will start thinking like rich people. Because we want a first-world mayor’s office: “The Cuauvegas Mayor’s Office”…

[Lisette]: I must clarify that what Tamara says in the sketch, that “she doesn’t like the poor,” is something that the mayor actually said in an interview in October 2021… This is the mayor:

[Sandra Cuevas]: I desire, and I bet on, an economy of the rich. Not of the poor. I don’t like the poor. I was poor once, and I don’t like the poor.

[Lisette]: And for Tamara it was important to emphasize this, because, for the people of Rechida, it is directly connected to what they are doing to popular art.

[Tamara]: What is she telling you? To completely erase the identity of the food that most of us eat every day. This contempt not only for the visual, but for this type of business, this type of commerce and the people who use it. That is the way to clean up, that is discipline, that is order. That there should be no expression of creativity. And much less from the poor.

[Lisette]: And this is not the first time that such an action has been seen in Mexico City. Aldo explained to me how, historically, local governments have tried to control the image of the city streets.

[Aldo]: This aversion to popular art and to the color of signs… Well, it is not new, is it? It is not something new that the mayor has come up with, but it has to do with something, let’s say a phobia… a historical phobia in the elites against popular art and expressions from the lower classes.

[Lisette]: One of the clearest examples, according to Aldo, is that of the pulquerías, where pulque is sold—a pre-Hispanic drink made from the fermentation of succulent plants like agave. It was a very popular alcoholic beverage in Mexico City…

[Aldo]: But there was a war, by the elites and with economic interests, since the end of the 19th century, because the beer business—which benefited from the government of Porfirio Díaz, which also favored European investment at the expense of national culture—wanted to eliminate pulque in order to own that market.

[Lisette]: Aldo told me that there was a lot of propaganda against pulque, that lasted several decades. Regardless of regime changes or the Mexican Revolution. Mainly it was said that pulque was in bad taste, that it was putrefied, unhygienic and something that pertained only to the lower classes.

[Aldo]: And with that there was also a war against pulquerías. What happened is that these taverns had very ingenious names and they had murals on the outside, murals of a popular style, colorful… They even spoke to people who couldn’t read, so that’s why they had to illustrate that pulque was served there, and there was a whole iconography of the maguey, the tlachiquero —the person who extracts the sap from the pulque— the drinkers, etc.… right?

[Lisette]: And as part of that war against pulquerías, murals painted by great artists like Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were banned. Which, similar to the signs on the more contemporary metal stands, had portraits of the owner, of his friends drinking pulque, or of animals.

Now, when the signs were erased from Cuauhtémoc, murals by artists who are now famous were not lost… But the work of the sign makers was lost.

[Aldo]: This is very interesting, because… notice that there is an idea, even to this day, of dividing things, right? Of saying that a sign maker is another type of muralism, another type of art, it is popular art, right? We use the term “popular art” to make it more accessible to people who will know what we are talking about. But actually, this term “popular art” is intended to… to clarify that it is not formal art. I think this is something very, very ugly, because it marginalizes sign makers and denies them the status of artists.

[Lisette]: This perception of the work of sign makers has put their trade at risk. Martín Hernández has been in the business almost all his life. He inherited it from his father, who started sign-making when he was 7 or 8 years old, in the 1940s.

[Martín Hernández]: Ever since I was a child, he would take me along to… to help him. Just to load the paint cans, the ladders, and clean the brushes.

[Lisette]: He was five years old, and little by little, Martín learned about this art from his father. How to draw objects, letters, to paint… And although being a sign maker was not always his dream, it became a full-time job when he had to drop out of Chemical Engineering at the university for financial reasons.

It wasn’t the worst thing in the world. Martin always enjoyed doing this job.

[Martín]: This job is for me… it’s a way of living, right? I think that a sign is something unique. And then on occasions, when I am resting, I have even dreamed of how to make or how I am going to reproduce that sign that someone is requesting.

[Lisette]: He worked on signs for political campaigns, signs for food stands or various shops. Sometimes he was even hired to replicate an illustration by another artist on the outside of trains or murals. On his best days he says he earned about a thousand dollars per week. It was a profitable trade that allowed him to support his family. But that has been changing in the last 15 years.

[Martín]: Well, as the printers got better, well, that made, the… the… well, the amount of, of work that we had decreased.

[Lisette]: Customers who previously waited patiently for hand-painted signs were increasingly looking to digital design and computer printing. Quick. Less expensive. Some sign makers began to buy the machines to do the work with printers. But those who lacked the money could not afford that luxury. So some of the workshops on the “street of signs,” where there were several of these businesses, began to close down. A few blocks from Martín’s workshop, there is now a printing press, right at one of the places where there used to be a sign maker’s workshop.

[Martín]: Many of us workers who are engaged in painting advertisements on the streets often seem to vanish.

[Lisette]: In the last six years, Martín, for example, went from having several orders a day to having one a month. He went from earning about 4 thousand dollars in months with regular work to earning less than 50 dollars. And so it becomes increasingly difficult for him to find new clients.

That is why having the signs erased by the mayor of Cuauhtémoc was so painful for him and for many sign makers. It puts them even more at risk.

[Martín]: It seems to me that it is a lack of understanding in terms of culture, because they are… they are erasing a tradition of more than three or four decades. It is very unfortunate because culturally they are putting us aside.

[Lisette]: Not only sign makers, but also merchants and business owners. Because through the signs, they were able to differentiate themselves from the rest. Advertise what they were selling based on funny drawings like happy pigs being cooked in a pot. But with the whitewashing of the stands and the Mayor’s Office logo, many of them saw their sales go down. And this was something the members of Rechida heard several times in the testimonies of the merchants they spoke with.

So, yes. I think it’s clear. Erasing the signs went beyond how the city looked. And that was what outraged Tamara the most.

[Tamara]: I know that out of context it could seem very ridiculous. But it’s not just that. It is the anger over all that work invested by the merchant men and women, and the anger of seeing the work of sign makers being considered worthless. And… in addition, not allowing them to work.

[Lisette]: With all that noise Rechida was making together with the city’s merchants, artists and sign makers, the media began to talk more and more about the subject.

[Journalist]: A few weeks ago, a decision by the Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s office of Mexico City sparked controversy in various sectors.

[Presenter]: They are replacing the signs on the street stands with the logo of the administration.

[Presenter]: Graphic artists raise their voices against the removal of signs by the Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office.

[Presenter]: Users of social media complained that the street stands of the Cuauhtémoc district have lost their identity.

[Lisette]: Several journalists spoke with the street vendors to find out what they thought of the mayor’s actions. The Nmas news outlet, for example, interviewed Marilú Mojica, owner of a taco stand:

[Marilú Mojica]: We had “Taco de Guisados Ramírez” painted right here. Right now we can’t use it because they put the blue stripe and the logo of the mayor’s office.

[Lisette]: When the journalist asks whether she likes how it looks, the woman shakes her head and laughs…

[Merchant]: (Laughter).

[Lisette]: Other merchants told how they had not even been given prior notice of the rules they were supposed to follow. This is Fernanda Mosqueda, interviewed by Televisa News:

[Fernanda Mosqueda]: Where is the opinion of the people? They didn’t even consult, and on top of everything, they charged us…

[Lisette]: Many merchants have told Rechida, and said in interviews, that the agents of the mayor’s office, in addition to demanding that they erase their signs, charged them for doing so… Between 150 and 200 pesos… Or else, they had to buy the white or gray pain—and that could cost them up to 350 pesos. However, in a statement issued by the Mayor’s Office, they do not mention whether or not they charged the merchants.

[Fernanda]: They came to us very emphatically saying that either we paid to have it put up, or they would shut us down. They came out of nowhere.

[Lisette]: Although many did not agree, they felt obliged to do it. Like this taquero named Toño in an interview with TelediarioMx:

[Toño]: What else can we do? If you want to continue working, you have to abide by orders.

[Lisette]: And others also said they could be penalized if they did not paint the logo of the mayor’s office. However, there were also some who, a little more timid, said that it was fine with them. In fact, The Mayor’s Office itself published a video where merchants said they agreed with the decision.

Finally, that outrage reached the ears of Mayor Sandra Cuevas. She first posted a photo on Twitter of her hugging the owner of one of the street stands. The tweet went like this: “For Doña Josefina, job offers at age 56 do not exist; she survives thanks to that stand, her only source of work and her life, which she requested to have painted with the logo of the Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office in order to adapt to the order and discipline of this new government.”

She also issued a statement informing that her decision was not about erasing the signs but about “maintaining order and cleanliness in the streets.”

And in an address to the Congress of Mexico City on May 20, to talk about her administration and its progress, she touched on the issue of labels:

[Sandra Cuevas]: The subject of visual images has nothing to do with an offense or an attack on the artists. It is not about that. The people who are engaged in making signs are people who have a trade. Today, the government of the Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office makes the decision to unify, bring order, and clean up. So the signs, which are not art, are removed. They may be the practice and customs of Mexico City, but they are not art.

[Lisette]: Tamara and the other members of Rechida were watching the broadcast.

[Tamara]: Well, it was like watching a game. We were all yelling at the screen, tweeting, talking on chats.

[Lisette]: In her address, the mayor went on to say that she, as an authority, would decide, together with a group of artists and neighbors, whether to remove or leave the logo of the mayor’s office. That they would have working groups to reach an agreement. And she clarified that there were many people who did like what had been done.

However, it seemed important to Tamara to have her acknowledge that she was open to dialogue, her response seemed like just a way of putting things off.

[Tamara]: What do you want working groups for? Stop kidding us, Sandra Cuevas. I mean, the solution is very simple. Revoke the imposition and guarantee that the people affected can recover their popular art, their signs and their identity, any way they want. But guarantee that there will be no retaliation against those who rebel. Guarantee it.

[Lisette]: That same day, the Head of Government of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, gave a press conference and spoke about the controversy over the signs. She said she did not agree with what the mayor had done because it meant erasing the city’s cultural identity…

[Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo]: And it is absolutely authoritarian to impose a single message from a City Hall instead of what has historically been popular culture in… in our city. So taking away creativity to impose a slogan from a mayor’s office does not seem right to me.

[Lisette]: She also said that merchants should not feel threatened by anyone, and if they wanted to recover their space, they should present their complaint to the attorney general. But that’s as far as the issue went.

Tamara told me that just having the mayor and the Head of Government respond publicly on the subject was already a triumph. For her and for the Rechida collective. Of course, that did not change anything in practice. What’s more, despite the controversy, Mayor Sandra Cuevas did not stop. She took her proposal of covering all the Cuauhtémoc stands with her logo to other spaces.

[Tamara]: So, the dude who makes his quartz necklaces now has the “Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office” canvas. And the last straw was that on Sundays in the park there are young ladies who give massages. Well, the massage bed says “Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office.” It became a damn dystopian nightmare.

[Lisette]: To Tamara, everything that is happening in her neighborhood is like living in another dimension where there is no creativity and no personal expression. Where everything is a photocopy: all the stands are the same, all the people dress the same and do the same thing. Something similar to what has been narrated so many times in science fiction books and movies.

And if this has taught Tamara one lesson, it is the desire to capture everything with her cell phone.

[Tamara]: I used to be a little more mindful when taking pictures. Why not choose the signs more carefully? And now I am aware that this can end at any time. I enjoy them much, much, much more.

[Lisette]: Not only enjoy it, but appreciate it, almost through the eyes of that girl that she used to be. By June 2022, three months after the bleaching began, some Cuauhtémoc stands began to rebel, although a little timidly and not fully erasing the trace of what the mayor’s office did. The merchants have begun to paint their signs with drawings of food, unique typography, dressed animals…

And not only that, but also an advertising agency and the TimeOut travel guide created the campaign, “Rótulos que pegan.” They hired sign makers to recreate the images that were removed by the mayor’s office on oversized magnets. So the people who have stands can remove them or put them up whenever they want, and in that way they avoid possible penalties.

Despite the impositions, the erasing of popular art, the signs find their way back. Because when you come down to it, that’s how a city is—it’s like nature.

Chaotic, colorful and beautiful.

Lisette is a senior producer at Radio Ambulante, living in Quito, Ecuador. This story was edited by Camila Segura and me. Bruno Scelza did the fact-checking. Sound design is by Andrés Azpiri with original music by Ana Tuirán and Rémy Lozano.

The rest of the Radio Ambulante team includes Paola Alean, Nicolás Alonso, Pablo Argüelles, Aneris Casassus, Diego Corzo, Emilia Erbetta, Camilo Jiménez Santofimio, Selene Mazón, Juan David Naranjo, Ana Pais, Melisa Rabanales, Laura Rojas Aponte, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, Barbara Sawhill , David Trujillo, Elsa Liliana Ulloa and Luis Fernando Vargas.

Carolina Guerrero is the CEO.

Radio Ambulante is a podcast by Radio Ambulante Estudios, produced and mixed on the Hindenburg PRO program.

Radio Ambulante tells the stories of Latin America. I’m Daniel Alarcón. Thanks for listening.